The Thinker's Tortured Body

The portrait of Zeno and the statue of Chrysippus are the only images of Stoic philosophers of the third century that can be identified with certainty. But there exist other portraits based upon the concept of thinking as a strenuous and laborious undertaking. For our purposes, it is not so crucial whether these actually represent Stoics, philosophers related to the Stoics, or even scholars of other kinds. Rather, we are concerned with particular paradigms for intellectual activity, as they developed at particular periods in time and were then translated into visual imagery.

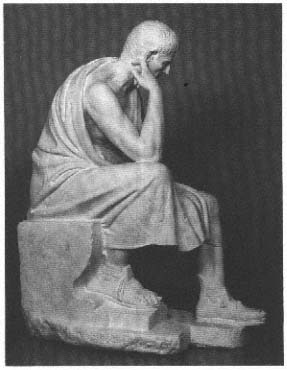

The badly damaged statue of a philosopher now in the Palazzo Spada, found without its head, was skillfully restored in the seventeenth century and completed with an ancient head that did not originally belong to it (fig. 57).[12] The baroque sculptor chose a portrait head with a pronounced "thinker's brow" to complement the pose of the statue, but unfortunately it belongs to the Early Imperial period. The motif of a man completely lost in his own thoughts, bending over and staring out, which we have already encountered in Early Hellenistic terra-cottas, has here taken on a new, more dramatic quality. The philosopher sits unobserved on a stone bench with carved, two-stepped base. To the ancient viewer this would signal an association with the gymnasium. The subject has drawn the crude mantle carelessly across his body. His legs are placed far apart in an almost unseemly pose,

Fig. 57

Statue of a seated philosopher. The Roman portrait

head does not belong. Copy of a statue ca. 250 B.C.

Rome, Palazzo Spada. (Cast.)

especially when compared with the dignified manner of the seated Epicurus (fig. 62). This is further emphasized by setting the right foot on the upper profile curve of the bench. In the bronze original, this foot probably rested only on the heel, to convey a restless, swinging motion of the leg, the psycho-motor expression of the inner tension of the thought process. (The copyist, who was understandably concerned to protect the front part of the foot, has added a stone ledge that serves no other purpose and so spoils the composition.) The right arm is drawn toward the head, with the elbow resting squarely on the agitated leg. Nor is the left arm propped calmly on the thigh; it is caught in an involuntary movement, with the hand clenched in a fist underneath the garment, like that of Chrysippus. Tension permeates

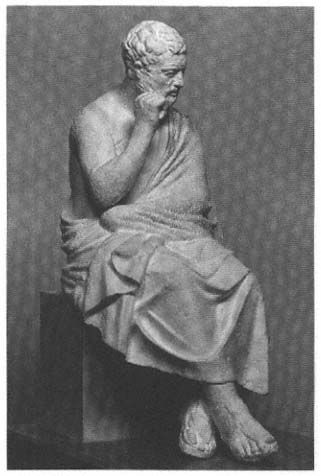

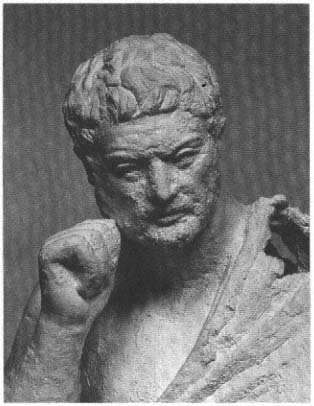

Fig. 58 a–b

So-called Kleanthes. Bronze statuette after a portrait of an

unidentified philosopher ca. 250 B.C. London, British Museum. (Cast.)

the entire body. The hand and the head have probably been correctly restored by the baroque sculptor. At any rate, the head must, like those of Zeno and Chrysippus, have expressed above all the strenuous effort of thinking.

The basic conception reminds one of the famous and ubiquitous Thinker of Rodin. The difference is that the ancient philosopher does

not in desperation look upon the abyss of Hell or the void. On the contrary, his mental efforts are presented as something praiseworthy, as a nearly Herculean labor. It is striking that this old man with the wrinkled belly has such powerful shoulders and arms. Various identifications have been proposed, on the basis of a fragmentary inscribed name, of which only ARIST . . . can be made out. So far no solution to the puzzle is possible. The motif of mental effort would indeed suit a Stoic, yet we should note another aspect. This is evidently a solitary thinker, a new kind of paradigm, which hardly seems appropriate for a teacher.

A related work of the same period, unfortunately preserved only in small-scale copies, is a seated statue (fig. 58a) that Schefold wanted, on

the basis of the gesture, to identify (though without conclusive arguments) as Kleanthes of Assos (331–232 B.C. ), the favorite pupil and successor to Zeno, of whom we have already heard.[13] The artist who created this statue was once again primarily interested in a careful observation of certain psycho-motor reactions of the human body in a state of extreme mental concentration. Only a bronze statuette in the British Museum gives some idea of the lost original. It renders the powerful and fleshy body and the full face of a man who has not yet reached old age (fig. 58b).

At first glance, this thinker seems to be comfortably seated with his legs crossed. But in reality, he too is completely caught up in his intellectual effort. Like the Spada philosopher (fig. 57), he is oblivious of his surroundings, and the act of thinking has tensed his entire body, removing him from the world around him. Both arms are caught in spontaneous and unconscious motion. The left pushes and pulls the garment to the side, while the right seems not so much to support the head as to push it to one side. The fabric of the mantle, which had been properly draped, has as a result slipped to the side. Both hands make a fist, and the feet are nervously entwined and pressed against each other. As in the case of the Spada philosopher, this uncontrolled motion is emphasized by a particular detail, the left foot resting in an extremely precarious manner, with only the edge of the sandal's sole touching the ground. In other words, the right foot has been moved up and down by the agitation of the left foot.

If we recall the pose of Euripides and of the elderly men on Late Classical grave reliefs (figs. 31, 32), it will be clear just how flagrantly these two seated statues flout the conventions of proper civilian dress. In both instances, the artist employs a carefully observed body language in order to visualize an inner tension and agitation. In the face of the bronze statuette, mental concentration is expressed not only by the contraction of the eyebrows and forehead, but in addition by the open mouth. One might be tempted to take the short and closely trimmed beard, similar to that of Chrysippus, as an argument for identifying the subject as a Stoic, but there are too few reliable copies to permit a specific identification.

It was only natural that this new image of thinking as a laborious

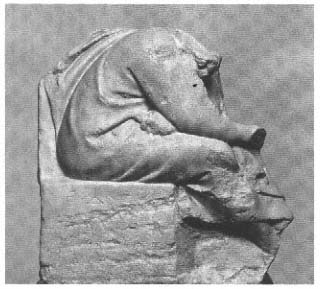

Fig. 59

Relief with the figure of the mathematician and astronomer

Eudoxus (ca. 408–355), his body bent over. Budapest,

National Museum. (Cast.)

process that manifests itself in the entire body also affected the visual imagery of famous intellectuals of the past. When, in the following chapter, we consider the emotional, sometimes almost violent facial expressions of these portraits of thinkers, we shall have to imagine them combined with correspondingly agitated bodies. Unfortunately, there are very few copies of the bodies that went with such portraits preserved in Roman decorative art. One exception is a statuette of Antisthenes from Pompeii, who sits with the legs tensed and, like Demosthenes, holds his arms still with hands clasped. But this type is probably not derived from a public honorific statue.[14] A particularly impressive example is the famous mathematician and astronomer Eudoxus of Cnidus (fourth century B.C. ), who broods on his equations on a relief fragment of Early Imperial date (fig. 59).[15] His arms clasped and legs crossed, he sits leaning far forward on a simple block of stone, like the statue of Chrysippus. His right hand reaching out could have

held a staff with which he drew in the sand. The compact and somewhat cramped composition seems to be derived from a statue of the Middle Hellenistic period. Modest works like this one are particularly valuable, because they give us at least some idea of the variety of body types and poses that could be employed to express the notion of concentrated and strenuous mental effort.