Roman Copies, or Through a Glass Darkly

Regrettably, we cannot move directly from these preliminary remarks to the subject at hand without a brief detour to consider what I call the foggy mirror in which we must view much of the portraiture of ancient intellectuals. It is a fact that almost all portraits of the great Greek poets and thinkers are known to us only in copies of the Roman

period. This means that each individual case is open to difficult, sometimes insoluble problems of reconstruction, analogous to the philologist's textual criticism. I will spare the reader in the present context a long excursus on the methods of so-called Kopienkritik .[10] But it is a fundamental principle of any historian that before he can use his primary sources and evaluate their importance, he must ask why and for what purpose they were created in the first place.

In our case, this question leads us straight to an essential chapter in the history of the image of the intellectual. These copies served specific purposes for the Romans that had nothing whatever to do with their original function as honorific statues in the agora or dedications in sanctuaries. For the Romans they functioned as the icons in a peculiar cult of Greek culture and learning, a topic I shall pursue in some detail later in this book. For the moment, let us just cast a critical eye on these copies, in consideration of their usefulness for the reconstruction of the lost original.

Since the Romans were primarily interested in the faces of the famous Greeks, which they believed they could "read" in the same way as modern critics do, they usually had only the heads copied. Of course such a bust or herm was also cheaper than a life-size statue and took up less space.[11] But Greek artists had produced only full portrait statues, into the Late Hellenistic period, and for the Greeks, from Archaic times on, the true meaning of a figure was contained in the body. It was the body that expressed a man's physical and ethical qualities, that celebrated his physical and spiritual perfection and beauty, the kalokagathia of which we shall presently have more to say. The most important qualities transcended the individual person, for the function of the portrait statue was to put on display society's accepted values, through the example of worthy individuals, for a didactic purpose. Personal and biographical details were of lesser importance.

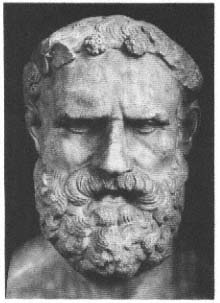

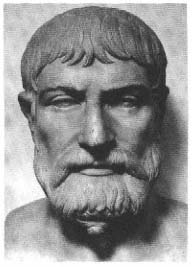

The portrait bust, which largely shaped the reception of Greek portraiture in the Roman Empire, arose first only in the course of the Hellenistic period.[12] Just one example may serve to illustrate how much is lost in this reduction to only a head, and what problems and uncertainties it creates for a proper interpretation. How are we to interpret the vigorous expression of this High Hellenistic portrait of a

Fig. 4

Head wreathed in grape leaves,

of the same type as the old singer in

fig. 79. Paris, Louvre.

poet, preserved in several herm copies (fig. 4)? What kind of a body should we imagine went with such a head? Would we ever have guessed that this is the expression of an impassioned singer, moving in rapt emotion to the music, as we now know thanks to the chance discovery of an almost fully preserved statue (cf. fig. 79)?

A further problem is the reliability of Roman copies of the heads. The issue is not only one of the competence of the sculptor, but of the level of interest, or lack of interest, on the part of the original buyer. There were passionately cultivated Romans who sought in such statues conversation partners, who used them, as Seneca says, as incitamenta animi (Ep. 64.9–10). These individuals presumably wanted carefully detailed sculptures of high quality, but that does not necessarily mean the same thing as faithful copies. The knowledgeable Roman patron had his own preconceptions of the Greek subject and was looking for

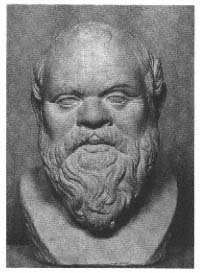

Fig. 5

Socrates. Roman copy of a Greek

original of ca. 380 B.C. (Type A).

Naples, Museo Nazionale. (Cast)

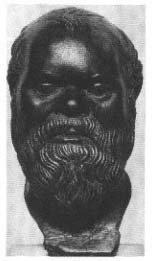

Fig. 6

Socrates. Post-antique bronze cast after

a now lost Roman copy of the same

Greek original as fig. 5. Munich, Glyptothek.

the kind of "talking head" that would reveal something of the subject's character and work. The obvious solution was to take a face that did not seem expressive enough and embellish it, if necessary with physiognomic detail. We may see a good example of such embellishment in the finest of the copies of the earliest Socrates portrait, an Early Imperial bust in Naples (fig. 5). Only recently has a careful comparison with other copies of this type revealed that the gentle smile that distinguishes this face must be an innovation of the copyist, an attempt to "humanize" the Silenus features and, perhaps, to suggest a touch of irony. A bronze head in the Munich Glyptothek, however, seems to provide a reliable rendering of the original face (fig. 6). And yet the head is probably not even ancient, but rather a modern cast of a now lost Roman copy! This is, admittedly, an extreme case, but it does illustrate some of the constant perils we face in the study of Greek portraits and their transmission.

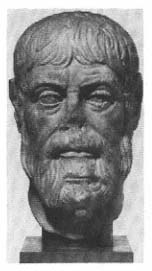

Fig. 7

Pindar. First-century B.C. copy

of a statue of ca. 460 B.C. Oslo,

National Gallery.

Fig. 8

Pindar. Second-century A.D. copy

of the same type as fig. 7. Naples,

Museo Nazionale.

In addition, the prevailing tastes of each period could play a considerable role. Since, for example, Augustan art did not look kindly on wrinkles, and youthful faces were the order of the day, the portraits of Menander made at this time were beautified in the same way as those of the emperor and his fellows. In the case of Menander, if we did not have more subtle copies from other periods, we would be ignorant of certain essential features of the original. By contrast, the last decades of the Roman Republic valued above all faces with emphatic physiognomic traits. For the copyists, this meant heads with extra wrinkles and more expressive faces. A striking example is the portrait of the poet Pindar (d. 446 B.C. ) that has only recently been identified. A very detailed copy of the first century B.C. in Oslo probably exaggerates the original's features of old age and adds a realistic quality to the flesh and skin texture unknown in the period when the portrait was created (fig. 7). An equally finely worked head in Naples (fig. 8), on the other

hand, assimilates the poet so fully to the style of the Hadrianic period, especially in the eyes and facial expression, that one could take it at first glance for a likeness of one of that emperor's contemporaries.[13]

But it was the lack of interest on the part of Roman patrons that took a far greater toll on quality and fidelity to detail. Perhaps no group of Roman copies can claim as many examples of hasty workmanship and poor quality as the portraits of the Greeks. The chief culprits are serial and mass production. Portrait herms were often displayed in villa gardens lined up in long galleries. They were simply part of the decorative scheme of wealthy homes, like the furniture, completely divorced from any cultural interests the owner may have had. There were even instances where hundreds of such herms were arranged alphabetically, providing nothing more than a visual dictionary of Greek learning. Phrases carved on the herm shaft—a snatch of poetry, a saying of the philosopher, or even a quick biographical sketch—served as mnemonic devices for rudimentary education (cf. p. 208).[14] In these circumstances, obviously, quality and detail were of secondary importance, and even the names and quotations on the herms could get mixed up. But the most grievous loss that results from this mode of transmission is any secure information on the specific location of the original portrait, its setting, and the occasion for which it was put up.

But I do not want to belabor this bleak situation any further. Rather, I propose to show, in three detailed case studies, how, in spite of the unpromising state of the evidence, we can indeed reach some secure answers to the question of context posed earlier. These examples belong to the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and thus are among the earliest portraits that we have. In view of the meagre amount of material preserved, we can hardly come to any general conclusions. But in each of these three instances we shall encounter certain features that turn out to have a general applicability to the study of the portraiture of Greek intellectuals.