A General in Mufti: Models from the Past

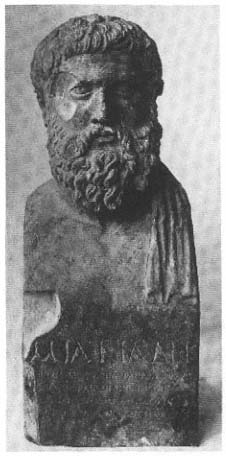

It was not only the great intellectuals who received such monuments as part of this collective act of remembrance, but other famous Athenians from the city's glorious past. A good example is the posthumous statue of Miltiades, who had led the Athenians to victory over the Persians at Marathon. Unfortunately, only three copies of middling quality preserve the head of the statue created about the middle of the fourth century or a bit later.[34] Despite the rather limited evidence at our disposal, we may make one important inference on the basis of an inscribed herm in Ravenna (fig. 36): the great general was not depicted in helmet or nude, or in armor, as would be usual in the fifth century, but rather in a civilian's mantle, like Socrates and the tragedians. The programmatic message is unmistakable: even the victor of Marathon, after his great triumph over the Persians, had returned to civilian life, an exemplary member of the democracy in the spirit of egalitarianism (his conviction for treason and subsequent death in prison conveniently forgotten). This message is here underlined by the particularly expressionless face, which, when put alongside portraits such as those of Pericles and Anacreon, can signify only a complete self-control. The transformation of Miltiades into an average citizen is all the more extraordinary in as much as the Athenians had long been familiar with portraits of strategoi who were depicted as such, and, as the example of Archidamus makes clear, knew well what the face of a man bent on power could look like.[35]

The statue of Militiades will most likely also have been set up by the polis. Indeed Pausanias (1.18.3) saw in the Prytaneion statues of both Militiades and the other victor over the Persians, Themistocles. And both had been reused by the Athenians in the Imperial period to honor contemporary benefactors, one a Roman, the other a Thracian—a not-uncommon frugality. Pausanias' comment on the "rededication" of the statues is a strong argument for identifying the original Militiades with the type preserved in the herm copy. Assuming the statue was a standard figure in long mantle, the reuse would simply have been a matter of replacing or reworking the head, whereas a nude or armed

Fig. 36

Herm of the general Miltiades. Antonine

copy of a portrait statue ca. 330 B.C.

Ravenna, Museo Nazionale.

statue of the strategos would have presented much greater problems.[36] When we consider all the traditional political associations of the Prytaneion, it seems a reasonable supposition that these two statues of great commanders also belong to the time of Lycurgus. This cannot, however, be confirmed by stylistic arguments, since the portrait of Miltiades could date as early as ca. 360 B.C.

Quite apart from the question of its date, the portrait of Miltiades once more lends support to our interpretation of the statues of the tragedians in the Theatre of Dionysus, as well as that of Socrates in the Pompeion, as paradigms of the good Athenian citizen. In these honorific monuments, the intellectual qualities of the great writers and philosophers of old were of as little concern as the martial valor of the generals. Rather, by representing the great Athenians of the previous century as if they were outstanding contemporaries instead of giants of a bygone era, the impression was created of a seamless continuity between past and present. We are dealing here with a self-conscious act of collective memory, not with a nostalgic reverence for remote and inimitable figures, as will be the case later on.

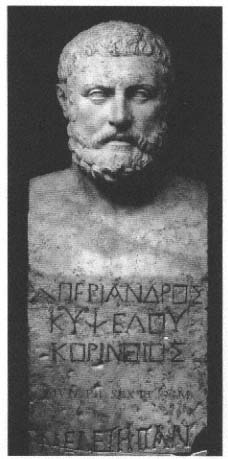

This attempt to recall and incorporate the great men of Athens's past in the present had not, however, started with Lycurgus. Portraits honoring Lysias and Thucydides, whose furrowed brows we shall return to shortly, had been put up a generation or two before Lycurgus' dedication of the tragedians.[37] Some time after Lycurgus, apparently, statues of the Seven Wise Men were put up, again in the guise of distinguished contemporaries: even Periander, tyrant of Corinth, was converted into a good citizen (fig. 37)![38] Indeed, we may suppose that almost all portrait statues of the great men of the fifth century that were put up in Athens in the fourth century had the same kind of exemplary function. But under Lycurgus this form of didactic retrospection, when coupled with other measures, first took on a particularly programmatic character. Thus it makes little difference for our understanding of them whether the statues of Socrates or Miltiades actually belong ten or twenty years earlier or later.

The Athenians always felt that their loss of primacy in the political and military sphere was compensated by a cultural superiority to other Greeks, evidenced in their democratic constitution and the Attic way of life that they considered unique, as well as in specific accomplishments such as the staging of great festivals, the Periclean buildings on the Acropolis, and even the works of the great playwrights. The strategies employed to sustain this notion included the elevation of daily life to the level of aesthetic experience, along with the continual cultivation of the memory of the great events and figures of the past. In the

Fig. 37

Herm of Periander, tyrant of Corinth, as one

of the Seven Wise Men. Antonine copy of a

portrait statue of the late fourth century B.C.

Rome, Vatican Museums.

visual arts of the fourth century we can already detect conscious evocations of High Classical style, so that the act of memory is cloaked in the appropriate artistic form.[39] The programmatic idea of a comprehensive paideia, as propagated by Isocrates, and the notion of Athens as the "school of Hellas" are both slogans that attest to the remarkable success of these efforts. After the collapse of their imperial aspirations, the Athenians succeeded in establishing a claim to cultural preeminence that they kept intact virtually to the end of antiquity. Later on we shall see how this phenomenon influenced the way many intellectuals saw themselves, even under the Roman Empire.