Preferred Citation: Moeller, Robert G. Protecting Motherhood: Women and the Family in the Politics of Postwar West Germany. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3c6004gk/

| Protecting MotherhoodWomen and the Family in the Politics of Postwar West GermanyRobert G. MoellerUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1993 The Regents of the University of California |

For Lynn Mally

Preferred Citation: Moeller, Robert G. Protecting Motherhood: Women and the Family in the Politics of Postwar West Germany. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3c6004gk/

For Lynn Mally

Acknowledgments

Without much help from many friends and colleagues, I never would have written this book. I welcome the opportunity to acknowledge my debts, though I know that I can never fully repay them.

I have benefited enormously from the friendship, encouragement, intelligence, and wit of Temma Kaplan. Perhaps more than anyone else, she first convinced me that I had something worth saying about women, families, and social policy in postwar West Germany. During four years in New York in the early eighties, I became acquainted with the German Women's History Group. I remain grateful for the responses, reactions, critical readings, and friendship of Renate Bridenthal, Jane Caplan, and Claudia Koonz, who offered me an intellectual and social community that still sustains me and that constituted a major reason for finishing the project. In addition, Atina Grossmann, Deborah Hertz, Marion Kaplan, and Molly Nolan consistently provided support and enthusiasm for my work. Individually and collectively, the scholarly efforts of these historians have profoundly influenced my research.

The years in New York also allowed me to become friends with David Abraham, Victoria de Grazia, Ellen Ross, Ioannis Sinanoglou, and Marilyn Young. Along the way, all took time from their own work to read and comment extensively on mine. My friendship with Carroll Smith-Rosenberg greatly enriched my scholarship; she continues to offer me a model of intellectual integrity and generosity that would be difficult to match. At key points, I have received additional assistance and guidance from James Diehl, Gerald Feldman, Geoffrey Field, Estelle

Freedman, Ute Frevert, Karin Hausen, Susan Mann, Gwendolyn Mink, Karen Offen, Robert O. Paxton, Susan Pedersen, Reinhard Rürup, Christoph Sachsse, Sharon Ullman, Judith Walkowitz, Steven Welch, and Linda Zerilli. Alvia Golden, Sara Krulwich, and Jane Randolph heard many of the stories that went into this book and reminded me to laugh.

Several years ago, Geoff Eley, Vernon Lidtke, and Volker Berghahn did much to convince the University of California Press that an outline might actually become a book. Their perceptive responses, both then and subsequently, their early vote of confidence, and their continued critical engagement with the project have helped to keep me going. Eley and Berghahn have commented on the work in progress, and their responses have always been valuable. Cornelia Dayton reassured me that even an historian of colonial America might find this book interesting. And James Cronin labored through an early draft, offering many good ideas for making it better.

Sheila Levine, my editor, has been much more than that from the beginning. She saw this project through from hazy start to finish. I think she was always far more certain than I that I would actually write this book. I also appreciate the considerable efforts of Ellen Stein, who did much to improve my prose, and Rose Vekony, who expertly guided the manuscript through its final stages. Their enthusiasm for my work came at exactly the right moment.

Heidrun Homburg and Josef Mooser greatly eased the trials and tribulations of research in Germany. They made Bielefeld an idyllic retreat, always providing a rare mix of intellectual camaraderie, friendship, and good food. In Berlin, Marlene Müller-Haas and Hansjörg Haas offered the same.

I came to the University of California, Irvine, in the summer of 1988. Since my arrival, Jon Jacobson and Patricia O'Brien have been truly exceptional colleagues and friends; they have seen me through the ups and downs of writing. Joan Ariel, women's studies librarian, and Ellen Broidy, history librarian, have given of their time and expertise as critics, researchers, and friends. Lynn Hammeras and Kathy White shared generously of their extensive knowledge of early childhood development. For more than forty hours a week they also cared for my daughter, Nora Mally, better than I could ever have hoped to, giving me the space and emotional energy to write about families and to be part of one.

Throughout my research, the staffs of many German archives helped

lead me through the documents and uncomplainingly filled the massive photocopying orders I left in my wake. Just as patient and professional were the interlibrary loan departments of Columbia University, the University of California, Santa Cruz, and the University of California, Irvine. Hans-Dieter Kreikamp of the Bundesarchiv (Koblenz) deserves particular mention. Only thanks to his considerable efforts was I able to dip so deeply into such a range of archival materials, never before open to historians.

I was extremely fortunate to receive ample funding for my work at two crucial points. A short-term travel grant from the German Academic Exchange Service (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst), a grant from the Spencer Foundation of Teachers College at Columbia University, and a summer stipend from the National Endowment for the Humanities allowed me to photocopy massive amounts of material during an initial foray into German libraries and archives. Support from the German Marshall Fund of the United States permitted me a luxurious year to sort through it. In the final stages of the project, funding from the Gender Roles Program of the Rockefeller Foundation gave me nearly as much time to write. Support from the Rockefeller Foundation, supplemented by a travel grant from the American Council of Learned Societies, also made it possible for me to participate in an international conference, "Women in Hard Times," in August 1987. There I received extensive responses to my work and shared in a truly exceptional intellectual experience organized by Claudia Koonz. Along the way, support from the academic senates, committees on research, and deans of humanities at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and the University of California, Irvine, and from the Focused Research Initiative, "Woman and the Image," at Irvine have funded research assistants and facilitated accumulation of even bigger piles of photocopies. Ann Rider spent many hours in the library chasing down references, allowing me to stay home and write.

The death of my father, H. G. Moeller, my daughter's third birthday, and final word from the University of California Press that it would publish this book all came at about the same time in July 1991. Historians love paradoxes, but I will not dwell on this one. My father, my mother, Marian Moeller, and my sister, Patricia Steimer, offered unqualified support and acceptance. Nora challenged all my assumptions about parents, children, and families, and kept things in perspective.

This long list of thanks only begins to suggest how extraordinarily

fortunate I have been over the years it has taken me to complete this book. Lynn Mally has lived with this project from the start, and she has had to hear enormous amounts about every stage of it along the way. Without her critical intelligence, patience, good humor, and friendship, I doubt that I would ever have finished.

Introduction

Writing in 1946, Agnes von Zahn-Harnack observed:

Hardly any other question will be so important for the future shape of German domestic life, for German culture and morals, and for [Germany's] reintegration into world culture as the question of the relation of the sexes to each other. [This question] will be raised in the arena of politics as well as economics, and in the specifically sexual arena as well. Every war and postwar period brings serious devastation and crisis, but defeated peoples are doubly endangered. They must fear the internal dissolution of many bonds that the victor can more easily maintain. The defeated party runs the risk of self-hate that allows it to throw away even what might be maintained.[1]

Zahn-Harnack's credentials qualified her as a keen observer of sexual politics. Cofounder of the German Association of Women Academics, author of a major history of the German women's movement, and the last president of the League of German Women's Associations (Bund deutscher Frauenvereine), the national umbrella organization that had brought together various strands of the bourgeois women's movement before its dissolution in 1933, she was also active in the political organization of middle-class women in Berlin in the late forties.[2] But no such qualifications were required to realize that a reassessment of gender relations would be a crucial part of rebuilding Germany after 1945.

Indeed, in many respects Zahn-Harnack expressed the obvious. Wars throw into disarray the domestic social order of the countries they involve. Particularly in the twentieth century, wars have been fought with

the massive mobilization of society by the state; the war at the front finds its counterpart in the war at home. While some men put on uniforms and try to kill those identified as the enemy, other men and even more women take on expanded responsibilities as workers, as single parents, and as sustainers of the domestic social and political order. Consequently, wars rupture boundaries that do not appear on maps—the boundaries between women and men. Unlike the boundaries between nations, these borders are never fixed; they are constantly challenged, questioned, and negotiated, though most people remain largely unaware of that process and live it without consciously participating in it. During wartime, however, state intervention into virtually all aspects of social and economic life alters the relations between women and men; the process is explicitly political, and its effects are immediately apparent. From the start, wartime changes are seen as temporary, extraordinary responses to extraordinary circumstances. At war's end, the social and political process of renegotiating boundaries commences, and again, the state's direct involvement makes explicit efforts to reestablish normalcy, to rebuild what has been destroyed, and to determine where the past can no longer provide direction. The politics of the family and women's status is essential to this general passage from war to peace.[3]

After 1945, the "political reconstruction of the family"[4] took place in all countries that participated in the Second World War, but the salience of gender as a political category in postwar West Germany was particularly striking. On the most basic, immediately recognizable level, relations between the sexes commanded attention because postwar Germany was a society in which women far outnumbered men. As the journalist and political activist Gabriele Strecker observed, in purely visual terms the high rate of male casualties in the war and the large number of soldiers detained in prisoner-of-war camps meant that in 1945 Germany was a "country of women."[5] This lasting demographic legacy of the Nazis' war of aggression combined in the late forties with the social dislocation and economic instability of the immediate postwar period to prompt widespread fears of a "crisis of the family." In a society where adult men were in short supply, this was a crisis of the status of women and gender relations.

Unlike the situation in Britain, France, and the United States, the problem for German women was not how to adjust to their postwar demobilization from nontraditional occupations; they faced challenges of a very different sort. Until the late forties under Allied controls, shortages of all necessities became worse than they had been before the war's

end, and the gradual release of men from prisoner-of-war camps, which continued into the fifties, delayed family reunions. War deaths meant that many families remained "incomplete" (unvollständig )—without adult males—and many marriages collapsed under the strains of long separations. The end of the war meant no end to the war at home.

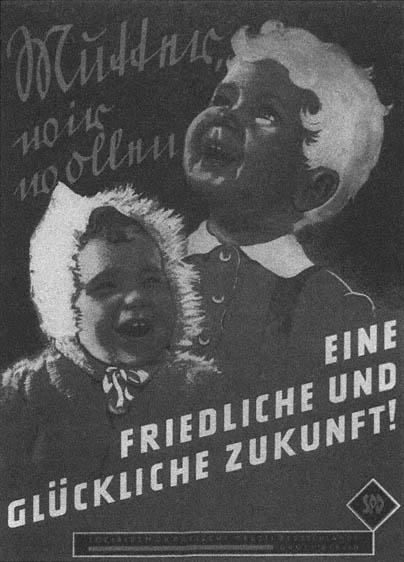

Women's hardships and the perceived disequilibrium of gender relations caused by women's altered status in the war and postwar years became central concerns of politicians and public policy-makers. For women and men, from the Social Democratic Party (SPD) to the conservative Christian-Democratic/Christian-Social (CDU/CSU) coalition, there was a broad political consensus that the war had placed particularly great strains on the family, and that "more than any other societal institution, the family had fallen into the whirlpool created by the collapse." This made the family "the central problem of the postwar era."[6] Everyone could agree that after the hard times of the war and its aftermath, the needs of women and the family deserved special attention.

This book explores how postwar West Germans approached these issues in the first decade of the Federal Republic's history. It focuses on public-policy debates over the definition of gender equality in the new West German constitution, family allowances, protective legislation and women's participation in the wage labor force, and family-law reform. Here, West Germans outlined blueprints for reconstructing gender in reconstruction Germany. Debates over these policies provide an exceptionally rich source for examining postwar Germans' attitudes toward gender relations because they engaged such a wide-ranging variety of witnesses and experts; employers, trade unionists, party politicians, ministers of religion, organized women's groups, lawyers and judges, medical practitioners, sociologists, and civil servants were all brought onto the stage, into newspapers and journals and before parliamentary commissions. In remarkably explicit terms, they voiced their opinions on women's work, family life, and motherhood. By exploring the extensive discussions and the implementation of specific measures, this book seeks to illuminate how established conceptions of gender difference influenced public policy and how state policy in turn shaped the conditions of women's social and economic status during West Germany's "economic miracle" (Wirtschaftswunder ).

It would be possible to pursue other thematic paths to the same end. The process of redefining "woman's place" in postwar West Germany occurred not only in social policies that expressed how families should be but in the lived experiences of families as they were; not only in the

sometimes arid debates of policy-makers but in novels, movies, and popular magazines;[7] not only in the halls of parliament but in the dance halls, where young Germans discovered the lures of rock and roll, along with new languages for expressing their sexuality and articulating generational conflicts; not only in debates about nuclear families but in women's organized protests against the threat of nuclear annihilation; not only in policies formulated at the national level but in measures affecting housing, education, and public assistance carried out at the regional and local level; not only in discussions of how to defend women and the family but in discussions of how to defend the nation from the perceived threat of communism; not only in laws designed to protect women workers but on the shop floor where women workers protected themselves.[8]

By focusing on one part of a more complex process, this book seeks to identify a set of questions; it does not exhaust possible means to find answers. In this sense, it is part of a history of women in the postwar period that is still very much in the making. Although this history is now being written, the post-1945 historiographic landscape still looks extraordinarily barren compared to the substantial literature on German women in the Kaiserreich and Weimar and under National Socialism.[9] In the few general treatments of the late forties and fifties that exist, the problems of reconstruction are the problems of Germans without gender.[10] This book insists that in any adequate account of postwar German history, gender must be a central analytic category. It analyzes key elements of the national politics of Frau and family in the postwar years and the forces shaping the political rhetorics available for describing relations between women and men. Debates over these concerns constituted a crucial arena where women's rights, responsibilities, needs, capacities, and possibilities were discussed, identified, defined, and reinforced.

Political responses to the "woman question" (Frauenfrage ) in the late forties and fifties drew on an already well-established repertoire. In pushing for women's equality and for a reform of family law in the fifties, Social Democrats and liberal middle-class women political activists returned to an agenda that originated in the late nineteenth century, when the Bourgeois Civil Code (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch) established explicitly patriarchal provisions governing marriage and family life as the law of the land. Demands for revising the law were as old as the law itself.[11] Concerns about structuring the wage workplace to meet the particular requirements of women's bodies, psyches, and souls were also well-established aspects of the state's attempt to provide women work-

ers with special treatment, trade unionists' and Social Democrats' struggle to improve women's working conditions, and the acknowledgment that most women wage earners worked a second shift at home.[12] Pressure in the fifties for family allowances to supplement the wages of the fathers of large families evoked long-standing working-class demands for the "family wage," conservative pronatalist enthusiasm for state support of families "rich in children," and anxieties, long predating the demographic impact of the Second World War, that family-size limitation would lead to population decline. At least since the late nineteenth century, the German system of social insurance, the foundation of the welfare state, aimed not only at addressing the crisis of democracy—the challenge to the Kaiserreich presented by the emergence of an organized working-class movement—but also at resolving the perceived crisis of demography —the falling birthrate. Policies tailored to meet the needs of male productive wage workers and their dependents also embodied a conception of women's essential unpaid reproductive work. Men's claims on the welfare state were based on their contributions as workers in the market economy; women's claims on the welfare state were based on their relations to others, as wives and mothers, as workers in the home.[13] When these political projects reemerged in the fifties, they were by no means entirely new.

Still, this book argues that when familiar themes surfaced in postwar West Germany they carried additional layers of meaning. In particular, they became part of a direct confrontation with the ideological legacy of National Socialist attitudes toward women and the family. In the categories of postwar West German politics, the Nazis had attempted to reduce women to breeding machines for the Volk , erasing the boundary between private families and public policy. For West Germans, restoring women to an inviolable family, safe from state intervention, was a shared objective. They renounced a past in which they had sought political stability in Lebensraum (living space) in eastern Europe; they replaced it with a search for security in the Lebensraum of the family, where a democratic West Germany would flourish. At the center of this construction was the German woman. In describing the debates over national policies affecting women in the fifties, this book emphasizes that by grounding conceptions of postwar security so solidly in specific conceptions of the family, social policy-makers articulated a narrowly circumscribed vision of women's rights and responsibilities.

For the political definition of women and the family, communism was just as powerful a negative point of reference as fascism. In her perceptive study, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era ,

Elaine Tyler May effectively documents how metaphors of "containment" influenced not only United States foreign policy in the fifties but also perceptions of gender relations and the family. "In the domestic version," she writes, "the 'sphere of influence' was the home."[14] In the Federal Republic of Germany, the context of the Cold War was even less subtle and more significant than in the United States, because West Germans were forcefully confronted with the example of their German-speaking neighbors to the east; the discussion of women's rights and responsibilities was frequently informed by a comparison with the status of women in the German Democratic Republic.

Debates over measures affecting women and the family constituted a particularly important arena for political self-definition in the Federal Republic because the family was among the few institutions that West Germans could argue had survived National Socialism relatively unscathed, a storehouse of uniquely German values that could provide a solid basis for postwar recovery. Helmut Schelsky, one of the founders of postwar West German sociology, published a much-cited study of the German family in the early fifties in which he expressed a widely held conception that in the wake of the "sudden and complete collapse of the state and economic order, as it took place in Germany, [the family] was able to prop up the individual person and was capable once again of carrying out total societal functions that the modern economic and state system seemed to have taken from it long ago." The family was a "vestige of stability in our social crisis."[15] This was a highly idealized vision, but in articulating this ideal, Schelsky and many other postwar West Germans demarcated a terrain where they could begin to shape not only policies affecting women and the family but also their vision of a democratic political order.

The urgency of this task was self-evident; the need for legitimate political identities was pressing in a country whose creation was the outcome of defeat in war and which was the product of another in a long series of revolutions from above, this time imposed from outside. The victorious Allies determined de facto that there would be two geographic and political areas called Germany, but in the fifties it was left to Germans—East and West—to create themselves. Much of this book is devoted to analyses of men's descriptions of women. Men—vastly overrepresented in parliament, in the government, in political parties, in trade unions, and in the medical, legal and academic professions—dominated debates over national policies affecting women and the family. In this book, however, I argue that when men specified their conceptions

of women's rights and needs they were also defining themselves and their vision of a just society; thus, this book attempts not only to examine the impact of postwar reconstruction on women but also to suggest what the politics of gender can tell us about the larger process of framing political identities in the first decade of the Federal Republic.[16]

The study of state social policies affecting women and the family in the past can provide a useful perspective on the problems of defining a feminist social policy in the present, which is another purpose of this book. It directly addresses many issues—the tensions between demands for women's equality and women's special treatment, the contradictions for women in many self-proclaimed profamily doctrines, and the difficulties of formulating a language of political equality that allows for a recognition of difference—that are of primary interest to feminist scholars and legal experts and that are central to discussions of social policies shaping women's lives. The interpretation of the West German experience offered here is a reminder that democratic welfare states can be both "friend and foe" for women.[17] Measures intended to "protect" women and to acknowledge the significance of their "natural" tasks are often responses to genuine social needs, but once in place they may limit the ways in which certain problems are perceived and the areas where solutions are sought, obscuring alternative conceptions and other potential solutions.[18] The historical study of the state's attempt to specify women's status, to delimit women's equality, to define families, and to reinforce conceptions of gender difference can thus alert us to the ways in which the identification of women's needs can all too easily lead to the limitation of women's rights.

Chapter One—

Emerging from the Rubble:

"No More Bomb Attacks . . . but Nothing More to Eat"

January 1933, the Nazi seizure of power; September 1939, the German invasion of Poland and the start of the Second World War; May 1945, the German defeat and surrender—these are dates familiar to everyone, events that frame most accounts of the history of National Socialist Germany. They define the chapter divisions in standard histories; they constitute a convenient periodization that describes the beginning and end of the Thousand Year Reich. May 1945 marks a "zero hour" (Stunde Null ), a new beginning, which will ultimately bring West Germans to the Federal Republic and the economic miracle. Can this periodization adequately make sense of German women's experience in the thirties and forties? Consider the story of Frau F., told to a social worker more than four years after the war's end:

In 1939, Frau F.'s husband was drafted. He went off to war, leaving her in Darmstadt with their three-year-old daughter, Gisela, and their son Willy, only a year old. At first, Frau F. and her children managed to survive his absence quite successfully. She found work as a postal carrier; her income, supplemented by the separation allowance paid to her as a military wife, allowed her to open a savings account and to indulge her children's food fantasies. Gisela could eat her favorite fruit and a sausage sandwich almost daily, and Willy stuffed himself with pancakes and fruit. Occasionally Frau F. had to work until midnight to maintain an orderly household, but she got some assistance from her mother, who lived in the neighborhood and helped with childcare.

In 1944, Frau F.'s hopes for an even brighter future ended. By then, Allied bomb attacks had extended farther and farther into Germany, and frequent alarms drove her and her children into basement shelters. On 11 September 1944, their apartment building was hit directly. Fleeing with her children from one shelter to another, Frau F. looked on horrified as Willy's clothes caught on fire. She extinguished the flames, but in the commotion Gisela vanished; no one knew what became of the child, and she was never found. With their burned clothes and flesh, mother and son struggled through Darmstadt to the home of Frau F.'s sister-in-law, whom they found sitting in front of her apartment, which also had been bombed out. She had escaped with only two suitcases and some linens. Joined by Frau F.'s mother, the two women and Willy spent several days outside in the ruins, sleeping in bomb shelters, before Willy and his grandmother were sent to relatives in the countryside. Frau F. and her sister-in-law found a room in the home of a doctor, a former employer from Frau F.'s past as a domestic; the doctor had been drafted, and his wife gave them shelter.

The village to which Willy and his grandmother fled became a battleground, leaving them homeless once again. Only after lengthy disputes with local authorities in Darmstadt did Frau F. obtain the official authorization for them to return to the city; reunited, they all shared a room with Frau F.'s sister-in-law. American troops seized Darmstadt, and black GIs occupied the building in which Frau F. and her family had found refuge. The three women took their things, and after a day-long search they found an empty basement that was still habitable. Willy became quite proficient at securing food from the soldiers; when his begging act failed, his growing expertise as a thief succeeded.

The return of Herr F. in 1945 made things no better. Though not injured in the war, he bore other less visible scars. Nervous and irritable, he was a chain-smoker in a society where ample supplies of cigarettes were available only on the black market. He flared up at the slightest provocation, and it was impossible to escape his wrath in the cramped basement. Frau F. found employment with the Americans right after the war's end, but she quit her job once Herr F. found work. Nevertheless, his ration card did not cover his appetite, and Frau F. could meet his demands for meat only by cutting back on what she consumed.

After nine months in the basement, local housing authorities assigned the F. family to three small attic rooms and a tiny kitchen, which they shared with Frau F.'s mother and Herr F.'s sister, who had been left a

widow by the war. Their quarters became only more crowded; within three years after the war's end, Frau F. gave birth to a daughter and a son. Her attempt to abort a third pregnancy by taking large doses of an over-the-counter drug was unsuccessful; another son joined the family.

Although thoroughly exhausted by her household labors and her responsibilities for her children, Frau F. feared going to bed before her husband had fallen asleep; she wanted to avoid his sexual advances. Her reluctance provoked his ire: Why, he asked rhetorically, should he work, if he was denied sexual pleasure? Her pleas that he might use a condom prompted only the response that prophylactics were harmful; when she refused him, he masturbated and complained the morning after that she was responsible for his headaches. Only the intervention of Frau F.'s mother and sister-in-law prevented her husband's verbal abuse from becoming physical. Although she proposed divorce, her husband would not accept this alternative. Economically dependent on him and tied to her children, she had little choice but to remain in the marriage.[1]

"Collapse" or "liberation"? According to one set of scholarly reflections marking the fortieth anniversary of the Nazi defeat, these were the two conceptual frameworks available to Germans for understanding 8 May 1945, the day of German capitulation.[2] German women who had suffered under National Socialism because of their religious or political beliefs, or because of their failure to fulfill racist Aryan standards, doubtless experienced May 1945 as a liberation. The end of the war also was the end to oppression for many women in Nazi-occupied territories and for women forced from their homelands to perform forced labor in Germany during the war. Unlike the sufferings of Frau F., the hardships of these women had been caused not by Allied bomb attacks but by the policies of the German government during the Third Reich.[3]

For those who had embraced the Nazis' policies, the war's end marked a depressing and disillusioning conclusion to a grand experiment. Doris K., born in 1924, an enthusiastic Nazi and member of the League of German Girls (Bund deutscher Mädchen), recorded her memories of the war's end in a poem:

The blue, sun-filled days

are lost and scattered—I hardly know how.

I barely carried their touch in my heart.

We loved them. And we do not shed tears over them.

The star-filled nights, full of love,

are dreams from another time.

And if it were to stay spring outside forever—

they are far away—God only knows how far.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Yes, it is day—but gray surrounds the earth.

Oh, it is night—but there are no stars.

And God, with his inscrutable mien,

is as far from us as he once was near.[4]

Day turned into night. A distant God. Though not necessarily in such adolescent, maudlin terms, 1945 represented a decisive turning point, a complete collapse, for Doris K. and others who had believed they were the promise of a new Germany. A sudden twilight had also arrived for the zealous, ideologically committed, and often completely unrepentant leadership of Nazi women's organizations.[5]

However, for the majority of German women who met the racial and political criteria of National Socialism but for whom the politics of the Nazis had been of little or no direct interest, the war's end constituted no such clear break, neither liberation nor collapse. The defeat of the Nazi regime represented not a rupture with the past but rather a moment in a continuum of hardship and privation that had begun with the Soviet Army's victories in the east and extensive Allied bombing of German cities in 1942 and 1943.[6]

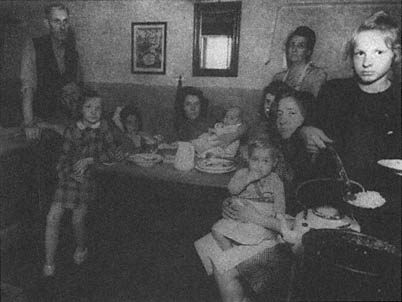

Stories like Frau F.'s, recorded by social workers and sociologists in the late forties, provided the basis for an extensive investigation of the perceived crisis of the family in Germany after the war. Allied bomb attacks had leveled cities, decimated housing stock, and disrupted the transportation network. In areas of heavy industrial development, such as the Ruhr, the destruction was particularly extensive, and in some areas, as few as four percent of all apartments remained undamaged.[7] "Women of the rubble" (Trümmerfrauen ) assumed a mythic status in accounts of the postwar period, as they literally cleared away the ruins of German cities to make way for a new beginning.

Social observers also described the "rubble of families" (Familientrümmer ) and the "broken souls" of men. Removing these social and psychological ruins and "rebuilding men" (Wiederaufbau der Männer ) was essential, and as accounts of this devastation made apparent, this too was women's work.[8] Hilde Thurnwald, who spent much of 1946 and 1947 studying 498 Berlin families, anticipated the criticism of those who might argue that she had paid inadequate attention to men. An emphasis on women, she explained, captured social reality because "at present in these families women have moved into the central position as providers."[9]

From the perspective of contemporaries, the war and its aftermath left women in positions of great responsibility; they played a crucial role in sustaining Germany in the last years of the war and in the rocky transition to peace. Forty years after the German surrender, Richard von Weizsäcker, the West German president, reflected: "If the devastation and destruction, the barbarism and inhumanity, did not inwardly shatter the people involved, if, slowly but surely, they came to themselves after the war, then they owed it first and foremost to their womenfolk."[10] The image of women as peculiarly equipped to overcome "barbarism and inhumanity" was not created from hindsight; rather, the president of the Federal Republic described a popular consciousness that already existed in the late forties.

Postwar social observers, however, who repeatedly remarked on how women had revealed enormous capacities by meeting the challenges of the last war years and the postwar crises, also emphasized that these stressful times had put women and the family at risk. The war had forced women to assume extraordinary burdens, and the war's end had only intensified their labors. The postwar accounts that articulate these perceptions correspond strikingly with reflections recorded in a number of recent oral history projects and first-person accounts that illuminate how West Germans recall their exit from National Socialism. From both sources there emerges a picture of women as strong, yet threatened, self-reliant, yet vulnerable.[11]

Sociological investigations of the late forties designate women as victims of circumstances beyond their control; in oral histories conducted over three decades later, German women define themselves in the same way. Their stories focus on women's difficult times in the war and the scarcities and hardships of the postwar period, not on the economic recovery under the Nazis in the thirties or the years of stunning victories in Hitler's Blitzkrieg.[12] By identifying themselves as victims, women, even more readily than men, allowed themselves to avoid any direct confrontation with the horrors of the Thousand Year Reich. In addition, the Nazis' outspoken declaration of politics as a male preserve made it possible for women to claim that the regime's excesses were products of a state controlled exclusively by men.[13]

The circumstances of the postwar period hardly created an opportune moment for the large-scale entry of German women into public political life or for coming to terms with the ambiguities of the National Socialist past. A British observer, assigned to the Women's Affairs section of the forces of occupation, remarked in the summer of 1947: "The German housewife is facing a daily crisis which at any moment may turn

to disaster in the form of illness, unemployment, failure of rations, or, in a vast number of cases, the crowning calamity of motherhood. Facing these facts squarely, what inducement is there for women to exert themselves beyond their daily routines, much less to participate in anything as vague and complicated as politics or as burdensome as public affairs and civic government?"[14]

Frau Ostrowski, a Berliner born in 1921, restated this rhetorical question over thirty years after the war's end. Recalling a political meeting in Berlin in the late seventies, she had only disdain for

a historian who wanted to tell us that we should forcefully confront our past and that we should have started in 1945. I asked him, "When were you born?" "Well, '46." I say only someone who hasn't experienced that time can utter such nonsense. I mean, after '45 no one thought about confronting the past. Everyone thought about how they were going to put something in the pot, so that their children could eat something, and about how to start rebuilding and clearing away the rubble. In short, women had . . . no time at all to think about such things.[15]

To be sure, there were important exceptions to this rule. Particularly for women who had been politically active in Weimar, who had seen their organizations either disbanded or totally transformed under Nazi leadership, the end of the Thousand Year Reich marked a renewal of public political life.[16] But in the postwar years, politically active women were rare, especially among those who had come to adulthood during the Nazi dictatorship and had virtually no experience of democratic politics. Like Frau Ostrowski, many women were primarily concerned with "put[ting] something in the pot." They did not try to assess their share of responsibility for the bombs that had fallen or demand a political role in shaping a new Germany. Instead, most sought to reconstruct what the bombs had destroyed, to return to an imagined past of prosperity, peace, and security, and to maintain one source of constituted authority—the family—which the bombs had not leveled.

The language of "collapse" (Zusammenbruch ) to describe 1945 drew on the same vocabulary employed by Hitler in his analysis of 1918. In Hitler's metahistorical imagination, collapse was the product of long-term cultural decline, materialism, and the growing influence of the Jews. In May 1945, collapse conjured up nothing so grandiose; rather, it described the war's end without assessing responsibility for the war's beginning.[17]

There is no question that the suffering of many Germans, both during the war and after, was real. Jürgen Habermas, writing of the experiences of German prisoners of war, war windows, bombed-out evacuees, and

refugees during and after the war, reminds us: "Suffering is always concrete suffering; it cannot be separated from its context. And it is from this context of mutual experiences that traditions are formed. Mourning and recollection secure these traditions."[18] But Habermas also questions the motives of "whoever insists on mourning collective fates, without distinguishing between culprits and victims." To paraphrase Max Horkheimer, she who would speak of shortages and suffering must also speak of fascism. Immediately after the war, speaking of shortages and suffering or of families at risk was a way not to make this connection, a way not to speak of fascism. Rather, it was part of the stuff from which Germans constructed a shared past and an identity as victims.

For Germans engaged in this project, the "war and postwar years" (Kriegs- und Nachkriegszeit ) were fused, a strangely depoliticized episode in which the culprits were bomb attacks, extreme shortages, fears of starvation, and a victor's peace that left many men removed from their families. From the perspective of the postwar years, it was this combination of events that placed enormous strains on women and threatened the family's future. According to this scenario, preserving and restoring the family was not only the responsibility of individual women; it was a central part of a larger agenda for social and political reconstruction as West Germans moved from a troubling past toward an undefined future.

After May 1945, memories of the years of National Socialist rule before the Germans began experiencing reversals in the Nazis' war of aggression were as close to a vision of prosperity and stability as many German women could get. Thurnwald, writing in 1947, found it "remarkable" that

a growing number of families are looking backward—the flight into the past and better days, with which they mainly mean the Hitler years. The difficulties of the present make the past seem even rosier, not just for former party members but for other men and women as well. They forget the horrors of the war and hold onto [the memory of] what they had . . . then. Overburdened mothers, who without any significant help from others feel themselves almost crushed by elemental forces in their cold, frequently half-destroyed abodes, are particularly visible in this group. . . . Statements like "If Adolf were there, then there would be order at home" or "We had it better with Adolf" . . . can frequently be heard.[19]

Imagining a past in which "we had it better with Adolf" was indeed "remarkable," but it was not surprising. Seen from the forties, the thir-

ties constituted a vision of normalcy that could look quite appealing. The past in which "we had it better with Adolf" was certainly not that of bomb attacks and the declaration of total war in 1943. Rather, it was a past in which the Nazis had apparently been able to overcome the repeated crises of the 1920s, to get Germany out of the depression, to put the unemployed back to work, and to introduce other measures that eased the burdens of women whose primary workplace was the home. Both Nazi propaganda and practical economic policy assured Germans that things would get better and better; in the 1930s, there were many indications that for politically acceptable Aryans—by no means all Germans but still the overwhelming majority of the population—promises would become reality.[20]

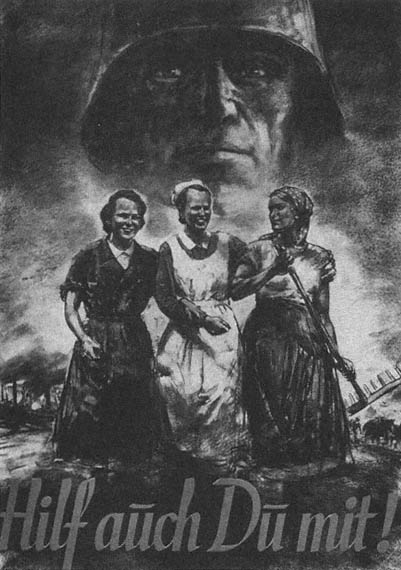

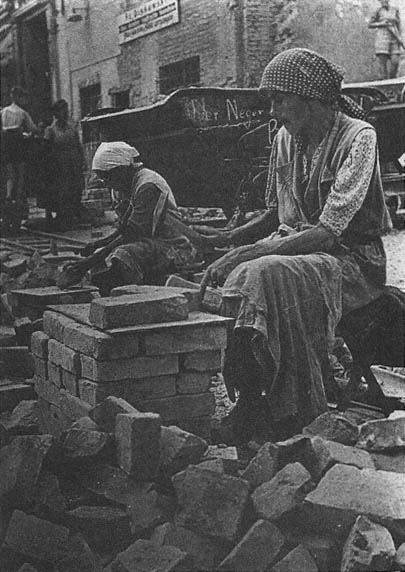

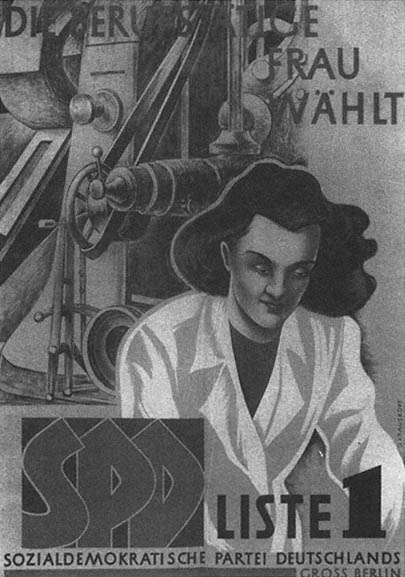

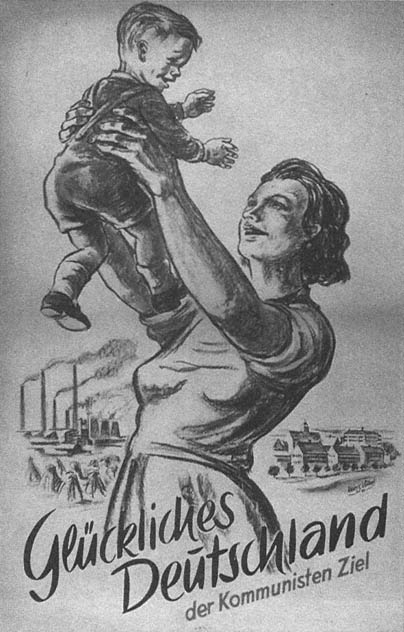

It is difficult to chart the boundaries between acquiescence, accommodation, acceptance, and support; there is no accurate gauge of women's attitudes toward Nazi ideology and policies that elevated the status of those women, judged fit according to the regime's racialist criteria, for whom children and housework constituted the most important employment.[21] The Nazis did not conduct public opinion polls to assess whether women accepted the ideological wrapping that surrounded material benefits or whether they might welcome the regime's support for their work without accepting identification as "mothers of the Volk " (fig. 1). However, such measures as marriage loans, family allowances, and tax advantages for families with children probably did much to increase the popularity of the regime among women, at least among those women whose families received these benefits.[22]

When they were first introduced, marriage loans were designed to bar married women from the wage labor force; eligibility depended on a wife's ending work outside the home. The loan was typically issued to the husband, not the wife. Young couples used the loans—roughly the equivalent of four to five months' wages for industrial workers—to furnish their homes. Beneficiaries could pay off one percent of the principal of the no-interest loans each month over a period of a number of years. Moreover, a woman's entry into reproductive labor cut the loan by one-fourth for each birth. Although many women continued to limit their families to one or at most two children, the woman who bore four children could close her family's account.

Some 700,000 couples met the economic, racial, and eugenic criteria to receive the loans—more than one-fourth of all couples who married between August 1933 and January 1937. In 1937, an economy at nearly full employment and continued economic expansion fueled by the

Nazis' armaments drive led the government to suspend the requirement that the new bride quit her job in order to qualify. In 1939, 42 percent of all marriages were aided by the loans.[23]

All families with children were given additional advantages through income-tax reforms that increased allowable deductions for children while placing a heavier tax burden on families with only one child and individuals and couples with no children. By March 1938, some 560,000 families, including in particular those with five or more children, received additional direct grants.[24]

At least in part, the rise in the marriage rate after 1934 may have reflected the impact of the marriage-loan program; for women and men who had postponed marriage during the years of economic crisis, loans of up to RM 1,000 could do much to make easier the early stages of married life. There is no evidence, however, that women who married were volunteering to become the combat troops in the Nazis' pronatalist campaign, the "battle for births." An increasing birthrate after 1933 probably resulted more from a return to trends disrupted by the economic crisis of 1930 to 1932 and the intensified prosecution of those seeking and performing abortions than from paeans to Aryan motherhood. Even coercive measures could not dramatically raise the birthrate above the level it had reached in the twenties before the onset of the Great Depression.[25] The thirties witnessed no convincing reversal of the demographers' downward curves that proved that Germans were "dying out."

The memories of some working-class women suggest how marriage loans and other forms of direct financial assistance to families had other consequences. Babette Bahl, a Ruhr miner's wife, recounted forty years later how she used her marriage loan to outfit the kitchen in her new home. When she gave birth to her first child, Frau Bahl purchased a bedroom suite with a small down payment. When the third child came, she bought a washing machine, then a bicycle and a sewing machine. She remembers the birth of her fourth child: "And so the little one arrived, and once again we got 250 marks from the state, in other words, from Hitler. . . . No debts, that's what my husband said, now we can really live." Frau Moritz, also a Ruhr miner's wife, was a member of the National Socialist women's organization, the NS-Frauenschaft. On the birth of her fourth child, she recalls receiving a shower of presents and coupons that she exchanged for shoes and a "bed, an entire bed for me . . . a white, wooden bed with a mattress, a new bed. We got a coupon: I couldn't believe it, that my husband and

I would be sleeping in a bed."[26] As the Nazis had hoped, the purchase of consumer durables contributed to Germany's economic recovery in the thirties; it also marked Frau Bahl's and Frau Moritz's memories of their children's births.

In the 1930s, the promise of a vacation for workers did not guarantee all workers a vacation any more than saving for the "People's Car" meant ownership of a Volkswagen. Nonetheless, such measures solidified support for the regime by previewing a better future; they indicated that the pledge to construct a new order was more than rhetorical.[27] Similarly, though Nazi marriage loans and family allowances neither benefited all Germans nor covered the cost of raising children, they did provide evidence that the elevation of hearth and home, motherhood and family, was not just symbolic. Policies that reminded women that "biology was destiny" reinforced patriarchal families; they ultimately most benefited men. But the sexual division of labor that designated housework and child-rearing as women's work was not created by National Socialist family policy, and the Nazis did consistently acknowledge the social significance of this work and introduced some measures to improve the material circumstances under which it was performed. This legitimation for the regime registered less in a soaring birthrate than in the construction of credibility and consensus.[28]

The Nazis did little to make attractive to women career alternatives to marriage, motherhood, and housewifery. Although many German women remained in the wage labor force in the 1930s and the absolute number of women going out to work increased, women's work opportunities and access to new jobs did not expand dramatically. The regime prohibited the employment of women in some occupations and greatly restricted their access to others, in part by limiting their entry into higher education except for such professions as teaching, which were considered appropriate for women. National Socialist rhetoric also criticized married women whose employment allegedly gave families an extra wage by taking jobs away from men. The assault on these "double-earners" (Doppelverdiener ) was not unique to the Nazis; many others, particularly from the political right and the Catholic Center party, had called for legally restricting the employment of married women in the last years of the Weimar Republic. But National Socialists could move from words to policy, and measures like the marriage loan scheme, introduced as part of the Law for the Reduction of Unemployment of 1 June 1933, were initially intended "to send women back to the home from the workplace."[29]

In industrial and white-collar occupations, gender-specific wage differentials remained substantial, and opportunities for women to move to better jobs were limited. The one exception was white-collar work in sales or clerical jobs, and a growing tertiary sector continued to employ more and more women as it had in Weimar. Still, even the attractiveness of this work was relative; employment in retail sales might be preferred to a dead-end job as an unskilled or semiskilled worker in industry or domestic service, but it held no promise of advancement or economic security.[30]

It is this set of circumstances that led Timothy W. Mason to conclude that "the drive for domesticity," in the realms of both ideology and policy, "really did meet the needs and aspirations (and aversions) of at least some of those women who had no wish to work in factories, offices and shops, and run a household as well."[31] Although Mason's language of women's wishes overstates the extent to which women were free to express desire when confronted with limited options, in this regard, Nazi Germany had much in common with all other social orders. In the 1930s, certainly, it is plausible that housewifery and motherhood might appear as preferred occupations for many German women. Psychologically and materially, Nazi policies rewarded women who made the home their primary workplace.

In an interview with an oral historian, Frau B., a textile worker who had been a trade unionist before 1933, recalls the transition from war to peace: "In fact, everyone was enthusiastic in the Third Reich, we were in good shape. The beginning was wonderful, everyone was provided for, everyone was doing equally well. . . . They often said that if they hadn't gone to Russia or moved against the Jews, then everything would have been all right."[32] In these selective memories, we were in good shape; they went to Russia and moved against the Jews. Germans enjoyed good times before 1939; Nazis went to war and created Auschwitz.

National Socialism's "drive for domesticity" ran into the brick wall of the exigencies of total war. Worsening conditions in the war at home coincided with the intensification of the government's efforts to mobilize both single and married women, the so-called silent reserve (stille Reserve ) into the wage-labor force.[33] The defeat at Stalingrad and the extension of Allied bomb attacks into the southwesternmost part of Germany combined to ensure that things would get no better.

Even then, Germans did not starve. The Nazis did everything in their power to avoid the severe shortages that had plagued Germany at the end of the First World War; the memory of widespread domestic unrest

in those years haunted Hitler, and this nightmare informed Nazi efforts to maintain the supply of butter while producing more and more guns. Nazi policy sought to increase domestic agricultural production at home, to develop substitute foodstuffs, to pillage the occupied parts of eastern Europe in order to maintain food supplies within Germany, and to restructure the agricultural sectors in occupied areas to meet the needs of the German war economy.[34]

Still, reports of the secret police revealed a rapid deterioration of domestic morale during the war, as rationing extended to more and more goods and the alternative economy of the black market flourished. By 1944, the retreat of the German army from areas occupied in eastern Europe meant a further reduction in the available food supply. In order to perform their daily tasks, women had to become accomplished at evading controls, scrounging, and functioning on the black market.

The war that was to bring the German people more, not less, greatly complicated women's unpaid labor. The sphere of domesticity expanded dramatically, as shopping meant standing in endless lines and scrounging, as cleaning extended to removing the rubble in the aftermath of bombings, and as mothering included rushing children into shelters at the sound of the first air-raid alert. In their constant search for food, women did not follow the Nazi prescription to place "the common good before self-interest" (Gemeinnutz vor Eigennutz ); their highest priority was their own survival and the survival of those dependent on them.

Waiting for hours in line for short rations, learning of the death of a male relative at the front, living in fear of Allied bombardment, leaving cities to avoid the bombs—it was in these forms that the war most forcefully and directly entered the lives of many German women. The establishment of routines under conditions of danger and uncertainty was work left largely to them. Under these abnormal circumstances, women's normally invisible work became quite visible.[35]

Although the flourishing black market graphically displayed class differences among women competing with unequal resources for dwindling supplies, the bomb shelters reduced all to the same "national community" (Volksgemeinschaft ). As Goebbels observed, "the bomb terror spares the dwellings of neither rich nor poor."[36] The conscription of adult males to fight the Nazis' war meant that far more women than men enjoyed this artificial leveling of social distinction in the war at home. However, neither this leveling nor women's contribution to maintaining social order created a sense of emancipation. The imposition of substantial burdens on women under circumstances of total war brought immense additional responsibilities, not expanded rights.[37]

Women did not respond enthusiastically to Nazi appeals to enter the wage-labor force. In fact, at the beginning of the war, some women used the allowances granted to military dependents as an excuse to leave wage work altogether. The regime responded quickly to labor shortages by importing unfree foreign workers, at least in part out of its commitment to limit the labor-force participation of German women. Polish women and men could be compelled to do the work from which German women should be spared. Still, these surrogates were not adequate to meet the demands of the war economy.[38]

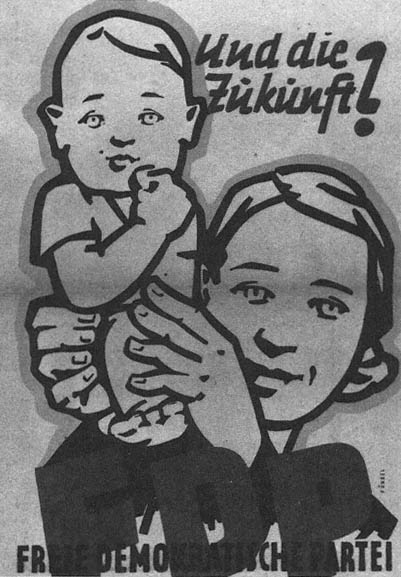

The move to total war after the German defeat at Stalingrad included a decided intensification of Nazi attempts to mobilize the silent reserve (fig. 2). By late 1943, however, the enormous difficulties that women confronted in their unpaid work made it even less likely that they would willingly seek additional work outside the home. For those women who did go out to work, access to many jobs remained restricted, and women's wages were still well below men's. Conditions of wage work became only more difficult as bombs destroyed factories and disabled urban transportation systems, as jobs included extra shifts as lookouts for Allied bombers, and as clerical tasks might entail removing rubble.[39] Nazi attempts to justify women's mobilization in terms of women's natural capacity for self-sacrifice prompted no apparent popular response.[40]

The enormity of women's second shift under the deteriorating conditions of the war economy made working-class women particularly resentful of middle-class housewives who were more successful at evading Nazi attempts to mobilize women for wage work. Perceptions of the advantages granted mothers with small children also produced strains among women across generations. A woman who had worked during World War I and raised her children in the 1920s found herself once again in a high-priority group for labor mobilization in World War II; with no small children in her family, she could not claim exemption on the basis of her responsibilities at home. She complained that "in this war the young women were well off. They got themselves some children so that they didn't have to work, and they got so much support that they could afford to have a wonderful life."[41] By 1944, Frau F., whose story began this chapter, would probably not have agreed.

The defeat of Nazi Germany was assured by March 1945, when the Red Army took Danzig and United States forces crossed the Rhine and entered Germany. By late April, Soviet troops pushing westward met

American troops coming eastward. By early May, the Red Army was in Berlin, and the German High Command had surrendered. But as Frau F.'s story makes clear, for some German women 1945 marked no radical discontinuity. Anna Peters, born in 1908, the daughter of a Social Democratic cabinetmaker, and married in 1934, remembers that spring:

The crisis of 1945: we had no more bomb attacks, but we also had nothing more to eat. Genuine starvation only really began for us in '45. The government that ruled over us [up until then] took care that there was at least enough to eat and that you could get full. But beginning in '45 that was no longer the case: then we starved, genuinely starved. You were never full. At no meal were you full. . . . When you met women standing in long lines in front of stores, their faces were all gray, almost black—that's how bad they looked, almost starved to death.[42]

Scarcity of housing, clothing, and food and the continued absence of many adult men who were never to return or who were in prisoner-of-war camps tied the last war years to the years 1946, 1947, and 1948.

Those fleeing the forward march of Soviet troops swelled a West German population that could not cover its own most immediate needs. By 1947, together with those ethnic Germans "expelled" (vertrieben ) from eastern Europe according to the terms of postwar peace settlements, refugees numbered over ten million. Another eight to ten million "displaced persons"—foreigners forced to come to Germany as workers during the war and others removed from their homelands by the Nazis for racial, religious, or political reasons, including survivors of concentration camps—had no choice but to remain in Germany while they awaited repatriation.[43]

The Big Three—the United States, the Soviet Union, and Britain—provided no clear strategy for confronting these pressing problems or for addressing the longer-term question of what was to become of Germany. Together, they had destroyed the Thousand Year Reich, but they could not agree on the form a newly constituted German political authority should take. In the absence of clearer formulations, the Allies fell back on agreements reached at the Yalta Conference of February 1945. At this meeting, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin had determined that together with the French, they would divide Germany into zones of occupation, leaving to an unspecified future the definition of more lasting territorial arrangements. When Big Three negotiators were joined by representatives from France at Potsdam in July 1945, they defined provisions for establishing German local self-government and mechanisms for licensing domestic political parties and other interest groups such as

trade unions, but they also made clear that it would be some time before Germans would be left alone to determine German affairs.[44]

Occupation hardly made German women's unpaid labor easier; rather, in many respects the end of the war meant that things went from bad to worse. The blessings of a mass-production capitalist economy promised by the western forces in their zones of occupation contrasted with the realities of worsening shortages. At the end of the war, the Allied decision to leave prices fixed while not reducing the supply of paper currency guaranteed a flourishing black market and hoarding, as too much money chased too few goods. The Allies maintained an official system of rationing and introduced five categories of entitlement, beginning with "heavy laborers" and ending with the "rest of the population," a broad category that included pensioners, housewives, and domestic workers. Escape from Category V, the "starvation or ascension" category (Hunger- oder Himmelfahrtkarte ), prompted some women to enter wage labor, less for money than to improve their status for rations. Others reportedly took jobs in specific industries like textiles because they were promised partial payment in kind; textiles in turn could be exchanged for foodstuffs on the black market.[45]

Women's magazines abounded with recipes for making something out of nothing, baking with flour produced from acorns, "doing laundry without soap," but theory translated poorly into practice.[46] It was women who most immediately experienced the shortages. In the winter of 1946–47—called the "eighth winter of the war" by some—seventh-grade schoolgirls in Nuremberg who were asked to describe their wildest wishes responded unanimously: "I wish for more to eat." One added, "I wish for a cake, but my mother can't make that, because we don't even have bread."[47] Mothers needed no school-sponsored surveys to know of their children's unfulfilled desires. The report of a social worker in Duisburg from 1947 corroborates Anna Peters's memories: "The unhappy housewives get the starvation rations only after waiting, standing in front of the stores for many hours. Because of these circumstances, bitterness and unhappiness are spices that unavoidably flavor every meal."[48] "Watery soup in the morning, watery soup at noon, watery soup in the evening, do nothing to improve [peoples'] spirits," was the understated observation of a social worker in Gladbach during the "epoch of calories," years when what went on the dinner table took on extraordinarily great significance.[49]

Scrounging and organizing consumption on the illegal black market occupied even more of women's lives than during the last war years; the

struggle for the most basic necessities became the chief preoccupation for many women. Women's unpaid labor took place as much in the streets as in the home. A family social worker in Duisburg regretted that "even members of respectable families go out to steal and take part in the black market. At every time of day and with complete openness, the black market is fully in operation."[50]

A mother's calculations became ever more complex in an economy in which money was the least attractive medium of exchange; price ceilings and rationing policies meant that few goods were available at official prices. On the black market, trade in kind was preferred to money of dubious value. Thurnwald captured the scene in one Berlin street where mothers saved half each month's ration of powdered eggs to trade for underwear and socks for their children. Women "compare whether it would be better for a child to be better fed or to have frozen feet."[51]

Under such circumstances, it was not surprising that a former Nazi adherent candidly admitted to Thurnwald in 1947, "Why shouldn't we have a positive attitude toward National Socialism? It created secure living conditions for us and many other people." This woman, who still quoted the speeches of Hitler and Goebbels at every possible occasion, employed an unexplained principle of selection to exclude them from other "big" Nazis to whom she attributed Germany's defeat. She and her husband praised "the good sides of National Socialism": "No one starved, no one froze, and if Hitler were to come back now, everything would fall into place in short order." Even self-proclaimed opponents of the regime might admit to Thurnwald that "Hitler was a bum, [but] nonetheless at least he made sure there was enough to eat."[52]

For women, sex had already emerged as a medium of exchange during the war. In her work on Württemberg, Jill Stephenson describes how women, left to run farms without sons and husbands, encouraged male foreign workers assigned to their farms to work harder in return for the promise of sexual relations.[53] After 1945, the foreigners who could offer benefits in return for sex were Allied soldiers, and in the sociological studies and official reports of the late forties and fifties there are frequent accounts of German women using their bodies as currency on the black market.

Fraternization became an emotionally charged symbol of the occupation of Germany. From a sympathetic perspective Thurnwald could observe: "Light, warmth, a cup of hot cocoa, the prospect of being able to spend a couple of carefree hours often brings a young woman into a soldier's apartment or prompts her to seek out a dance hall with her

friends." Not just the "material gifts of love" that soldiers could offer but also the promise of release from the constant pressures of daily life made relationships with the forces of occupation desirable.[54] For at least some observers, the fraternizer was no more subject to condemnation than other women, who found "uncles," men whom they did not marry but with whom they set up households.[55]

Other judgments were not so generous. A health officer in Neuss regretted that "among many there is a blurring of any measure of right and wrong," especially among "young women on their own, whose husbands are in prisoner-of-war camps, missing or dead, [who] have unregulated relations with men, with truck drivers, foreigners, and in any case with those who can get them food." Even more outrageous, according to this report, was the practice of some mothers who "systematically send their sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds (in one case, a twelve-year-old) into the camp of foreigners, Poles, in the American-occupied zone, to British soldiers, with the appropriate instruction on how to behave, in order to get food and cigarettes." The health officer admitted to ambivalent feelings about the behavior of these "inhuman mothers"; he conceded there could be no question that "today, those who are fundamentally honest [and who] only wanted to consume their rations would suffer a horrible fate."[56]

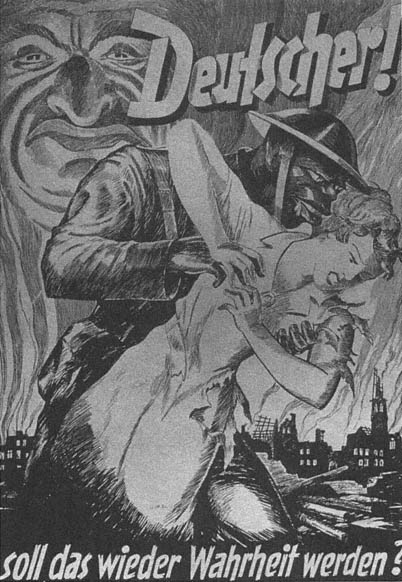

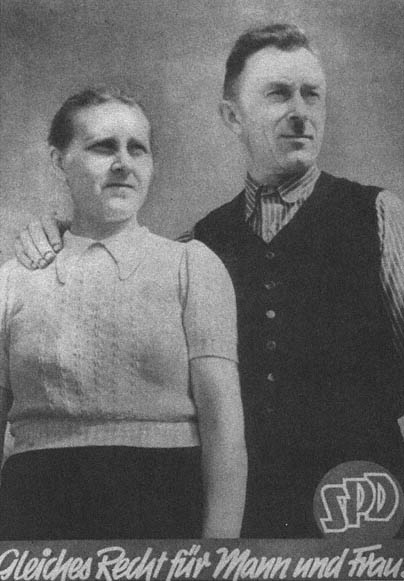

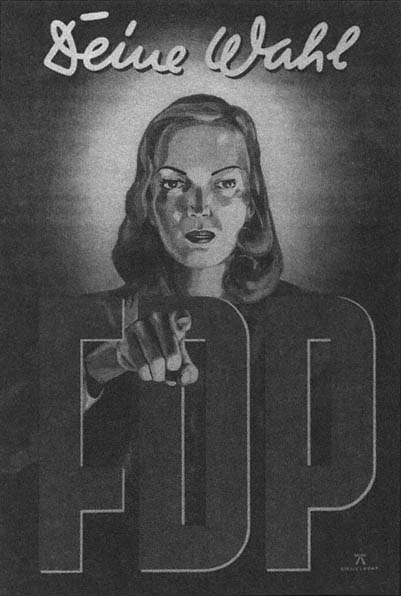

While the fraternizer might win some sympathy, she was also blamed; she embodied the image of a postwar woman beyond morality, a symptom of crisis conditions. Although the victim of rape by Allied soldiers could not be held responsible, she too indicated the inability of German men to protect German women. Reports of rape by black GIs, French Moroccans, or, in dramatically greater numbers, by Red Army soldiers, were also filtered through twelve years of systematic racialist propaganda (fig.3). Not only had German men failed to prevent the rape of German women; in popular consciousness, the rapist was often the "inferior" black or the "Mongol," a code word by which all Soviets were labeled as Asian. Contemporary commentary on rape focused far more on its implications for the male psyche than on what it meant for the health and well-being of women.[57]

Some observers determined the boundaries between rape and prostitution only with difficulty. Fears of rape and sympathy for rape victims blurred with suspicion that women had failed to resist or had succumbed to blandishments and material benefits offered by the Allies. Among those interviewed in a Ruhr oral history project, Ernst Stecker, a politically active metalworker, forty at the end of the war, underscores one

of his most vivid memories from the spring of 1945: "A Negro said: 'The German soldiers fought for six years, the German woman for only five minutes!' That's a fact from beginning to end. I was ashamed."[58] Rape, prostitution, and fraternization became disturbing signs of German surrender and defeat, of foreign occupation in a most literal sense, of a world in which German women's sexuality was outside of German men's control.[59]

Allied appeals for women to work for wages met with even more resolute resistance than Nazi attempts to increase women's rates of labor force participation in the years of total war. Mothers also held back their adolescent children from wage work; their service as scroungers represented a potentially greater contribution to the family's survival.[60] Compared to 1939, half a million more women were working for wages fifteen months after the war's end, but at least in part this increase reflected the flood of refugees and expellees, the Vertriebene from the Soviet-occupied east. Without savings or goods to exchange on the black market, women in this group had fewer opportunities to avoid working for wages, though in some cases their lack of adequate clothing or shoes presented another sort of impediment to labor-force participation.[61] Beginning in the summer of 1945, women between the ages of fourteen and fifty were legally obliged by state and provincial authorities to register with labor exchanges for work, but housewives and daughters still living at home were exempt. The military government had called for an end to sex-based wage differentials, but women's wages remained about forty percent lower than men's, and even in unskilled jobs women earned twenty to twenty-five percent less than their male counterparts.[62]

The Allies also confronted the determination of German laborministry officials to limit and label as temporary women's access to jobs held largely or exclusively by men. West German authorities deemed totally unacceptable a mobilization of women "following a Russian model" that would force women into occupations not suited for them. They vehemently demanded the reinstitution of protective legislation suspended during the war, leading one frustrated British official to call for a revision of the "luxurious German labour protection laws necessary in respect to women." Failure to undertake such steps would represent nothing less than a violation of the Potsdam agreement, which had stipulated that "the standard of living in Germany shall not be better than the rest of Europe," making it "inappropriate for us to enforce social legislation which gives German women a more favourable position in industry than that enjoyed by other women in Europe."[63]

To no avail, the Military Government lectured German labor officials that in the United States "women chauffeurs are considered better than men, [and] in addition, women could be employed as streetcar drivers, as watch-makers or as glaziers, while in the Russian zone, women have proven themselves in particular as traffic police, and assistants in the construction industry."[64] Allied officials were repeatedly exasperated by German officials' patent unwillingness to mobilize all women into a greater range of occupations and by what a British labor ministry observer, Mrs. B. P. Boyes, identified as a "marked prejudice in Germany against the employment of women in non-traditional occupations. The general feeling seems to be that women's place is in the home and that if she must work, she should confine herself to occupations which are 'womanly' such as dressmaking, clerical work, hairdressing, etc."[65]

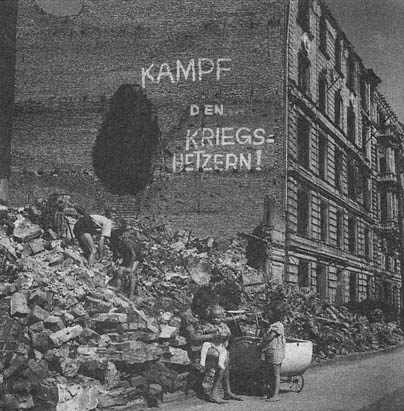

An even more significant barrier to labor-force mobilization remained the continued pressure on women to perform extraordinary forms of unpaid labor and the limited value of wages in the inflationary postwar economy (figs. 7 and 8). The implications were immediately apparent to an officer of the British Manpower Division, who soberly observed that "the earning of Marks which will not buy scarce commodities is not so important to the family as foraging for food, a duty which often falls upon the womenfolk."[66] Social workers in Frankfurt reported a common response among women exhorted to enter wage labor: "I can't afford to work, I have to provide for my family."[67] The labor minister of heavy-industrial North Rhine–Westphalia informed British observer Boyes in early 1948 that "at the moment, the monetary value of a ration card for cigarettes is worth more than a young woman's work for a month."[68] Boyes concluded that "the value of the currency is so low and the supply of consumer goods so scanty that the additional income to be derived from wages would be virtually worthless. Once the basic ration has been purchased there is little or nothing to be bought, except at exorbitant black market prices, or in exchange for goods."[69]

By 1948, Allied officials conceded that as long as women continued to play a crucial role as black marketeers and scroungers, attempting to mobilize those who were responsible for dependents was futile, serving only to heighten antagonism toward the forces of occupation. Allied officials realized that it would require currency stabilization and an end to the black market to increase the supply of available labor. They reasoned that the demographic legacy of the war—the fact that Germany was a nation with far more adult women than men—would restrict opportunities for many women on the marriage market, forcing them into the

labor market.[70] By early 1948, with currency stabilization close at hand and German self-government in the foreseeable future, the Allies gave up on efforts to increase the number of wage-earning women and to place women in jobs typically held by men.[71]

Those women who entered or remained in the wage-labor force before currency stabilization confronted enormous difficulties. Thurnwald provides a graphic description of the double burden of working mothers in the Berlin winter of 1947: "The mothers who work during the day in unheated firms have frostbite on their feet and hands, they suffer from a catastrophic transportation system, and at home they still have to manage a household where water pipes, drains, and toilets are frozen, and where carrying water and removing waste requires an additional effort of which they're incapable. They have no time for their children and because of their anger or exhaustion, they have no warmth."[72] The dilemmas facing working mothers were inscribed in the memories of Klara Steiner, a streetcar driver in Berlin after the war. Forty years later, she was still filled with self-reproach: "I should not have looked for work. . . . Today I'm convinced that I should have gone scrounging, so that I could have fed my children. With your earnings, you couldn't buy a loaf of bread on the black market for 100 marks. And my children suffered because of that; they never got full."[73]

More than three million German soldiers were killed in the war, and in 1945 nearly two million more remained in prisoner-of-war camps. The first postwar census, conducted in October 1946, meticulously recorded that for every 100 males, there were 126 females. In big urban centers, the official ratio was as high as 146 females to 100 males, the figure for Berlin. Although the chaotic circumstances under which this census was conducted meant that its results were probably unreliable, there could be no question about the general tendency it described.[74] More than dry statistics, the 1946 census articulated the widespread sense of alarm about the demographic imbalance created by the war. Comparing numbers of unmarried men and women in the "biologically most important age group," the census determined that for every 1,000 marriageable males, there were 2,242 available women. While predicting that the return of soldiers from prisoner-of-war camps would change this ratio, the census concluded that "the men are missing for around one-third of all women of child-bearing age." Within Germany's borders, there were nearly three million more married women than men between the ages of fifteen and forty-five, one indication of the number of men missing or in

prisoner-of-war camps. As late as 1950, when many men held as prisoners of war had returned home, there were still more than 130 women for every 100 men aged twenty-five to forty.[75]

The long-term significance of this demographic legacy found expression in a language that described a "surplus of women" (Frauenüberschuss ) and a "scarcity of men" (Männermangel ), abstract categories that blurred the distinction between economic and socio-psychological reconstruction and captured inadequately this lasting consequence of the Nazis' war of aggression. Not surprisingly, at least some women took exception to this linguistic condensation of their fate. Writing in Constanze , a popular postwar women's magazine, Helga Prollius complained of the formulation Frauenüberschuss: "What an ugly word! And what an even uglier meaning! A word that is taken from the language of trade and signifies nothing more nor less than a product, and at that a product of which there is a surplus, which is superfluous."[76] Still, such dissenting voices were exceptions amid a general consensus that the "scarcity of men" would have dire implications for rebuilding the German population.