4

Doing Ngoma

The Texture of Personal Transformation

Kuphilwa ngamutu. "We survive because of each other."

Xhosa proverb applied to ngoma

Mpimpa yoyo bana kina nkununu yanene nate ye bwisi bu kiedi. "This same night all dance a big Nkununu dance that ends at the break of day."

Kwamba Elie, Kongo ethnographer, describing a Lemba gathering in 1912

"Doing ngoma" is the central event in ngoma. It is the "dominant trope," the "symbol that stands for itself" (Wagner 1986:29–30) and defines the institution. "Doing ngoma" opens with a declarative statement, prayer, or utterance, then moves on to song begun by the one who makes the statement; as the call and song is developed, the surrounding people respond with clapping and soon singing begins en masse, and then the instruments enter in. This basic set of features, with many variations, may be found throughout the larger Central and Southern African setting. The Ndembu call it kwimba ng'oma , "to sing an ngoma" (Turner 1975:63). The Venda of the northern Transvaal also use the same verb to speak of nyimbo dza dzingoma , singing an ngoma, "drum" (Blacking 1985:41). The Kongo of Western Bantu "drum up" (sika ngoma ) a major medicine with a song, nkunga . In the Nguni-speaking setting in Southern Africa, the isangoma , diviner-healer, is one who (i -) does (sa ) ngoma. All of these references identify ngoma with patterned rhythm of words, the use of performance dance, and the invocations or the songs that articulate the affliction and the therapeutic rite.

Many song-dance performances punctuate the sufferer-novice's course through the white. Even after becoming a fully qualified healer,

the practitioner participates continuously in ngoma sessions. This chapter presents a single important example of "doing ngoma." In both content and structure, this ngoma performance reveals that here, in the consciously formulated exchange of song-dance, and in the movement of the individual from sufferer-novice to accomplished, singing, self-projecting healer, lies the heart of the institution. I believe it is a classic—that is, ancient and formative—institution in Central and Southern African healing.

Unfortunately, it has been least well studied of all the aspects of African medicine. Many scholars have missed the mark, in a sense, emphasizing only a limited aspect of it. Some have singled out only the healer-patient relationship for attention; others, the symbols; yet others, the plants. Many have followed trance behavior and assumed it is the central point of the ritual, without putting it sufficiently into institutional context. Very few scholars of African medicine and religion have bothered to look at the music. Scholars of African music, for their part, have ignored the therapeutic qualities, and intentions, of this kind of music.

Text And Texture In African Healing

Amandina Lihamba, in a recent article, "Health and the African Theatre," has described the relationship between health and performances of all kinds in Africa. "Health and disease are social phenomena with implications beyond the individual, the physical, and the present. Performances are often concerned with the maintenance of community and individual health, the prevention of ill health, and the restoration of health and with instilling survival knowledge" (1986:35). Examples include W. Soyinka writing about the cleansing of society, cosmic equilibrium, and society as sufferer; Muhando on the madness of social and economic success, and society causing sickness; and Hussein describing the evil of corruption, exploitation, oppression, and class divisions and aspirations as devils (Mashetani ) who have infiltrated society and need to be exorcised for health to be restored. Ngoma provides the fabric of personal transformation; it helps sort through personal or societal experience with prevalent metaphors and other types of knowledge.

There may be no close analogue in Western civilization to these combined features of ngoma. Lihamba and others' reference to theater and performance are accurate. However, for illustrative purposes I shall for

the moment argue that an approximation of such an analogue exists in the conjunction of Latin and Old French roots textus, textere , and contextus or contextere . These terms provide a picture of a fabric of meanings pulled out of a context and put into words. Textere refers doubly to "weaving a fabric" in the technical sense of putting together the warp and weft of cloth, as well as to the original written or printed words of a literary work, a single text. The con -text is where the separate threads are brought together into one fabric.

Ngoma brings together the disparate elements of an individual's life threads and weaves them into a meaningful fabric. It does this, particularly, through devices of mutual "call and response" sharing of experience, of self-presentation, of articulation of common affliction, and of consensus over the nature of the problem and the course of action to take. The ngoma text is created over the course of many months and years and finally is presented formally at the time of the sufferer-novice's emergence as a fully ready healer. In another sense the text of self-presentation is never completed, for as long as the ngoma participant lives, there will be moments and times of self renewal, in the context of others.

"Doing Ngoma": The Core Ritual Unit

The song-dance of ngoma may last all night, as in the Kongo example at the head of the chapter. Such a session is made up of many shorter units of song: the self-presented and the response. In the Cape Town setting, which will be featured here, it may be repeated by the same person (usually with a different song), or someone else "takes up ngoma" and "does his or her ngoma"—sa ngoma . The sequence of such units may go on for hours. It may occur within the context of events heralded as purification celebrations for established healers or as celebrative points in the initiatory course of novices. The familiar group ngoma song presentations may be seen at a wide variety of events within the local ngoma network. An important variant of the sufferer-singer presenting his or her invocation and song is for another singer to present the "case" of the sufferer. This may occur in the instance of a very sick individual, someone who has not developed her or his song or who cannot perform, or a senior healer who has suffered the death of a close kinsman and is being ministered to.

The case that will be illustrated is from a "washing of the beads" of a senior igqira/sangoma in the Western Cape following the period of

mourning of the death of her mother. Her sister and host of the event sang the leads, reiterating the death of their mother. The spoken openings to each unit narrated the days leading up to the death, details surrounding the death. It was thus in effect a requiem ngoma and a coming out of mourning of the descendant. Death is impure, but mourning and commemoration allow the ngoma practitioners to cleanse themselves and to "throw out the darkness" and to "wash the beads" with medicines—in Nguni pollution terminology, to replace darkness with light.

At the site of throwing out the darkness, outside, the same format is again repeated. For the spoken prayer parts, the novices (amakwetha) sit down for the declaration, then rise for the dancing and singing (fig. 9).

In the following pages I present a sequence of self-presentations (ukunqula ) and song-dances (ngoma) performed at the above event, first among senior sangoma and amagqira of the Western Cape, followed by a session by their novices.[1]

1. Ukunqula [by the senior healer whose mother had died, and who was being cleansed]: Sukube ndilthandenza ke xa kdisitsho kumama . In so saying I'm praying to mother. We'll leave having washed each other [repeated many times]. Kuphilwa ngamutu . We survive [or live] because of each other. While we say we came to "heal" here.

Ngoma: Bambulele umama ... They killed mama.

2. Ukunqula : You would have thought that the night "war" would have calmed down this [igqira spirituality]. But no, it doesn't. I'm in it, always facing a white person [at work], and maybe that's why I'm "on edge."

Ngoma: Balele phezu kweentaba zuLundi . The [ancestors] are sleeping at the top of the mountains of Ulundi.

3. Ukunqula : Let's camagusha now! Let darkness be replaced by light. Nizala [a relative], I want you to say for me to these amagqira and these visitors what we're here for, they're welcome.

Ngoma [in Afrikaans]: Wat makeer vandag, wat makeer? What's happening today?

Figure 9.

Plan of house, compound, and street in Cape Town township setting

where "doing ngoma" was performed, in the context of "washing of the

beads" of senior healer Adelheid Ndika following her mother's death:

(a) living room and intermediate ritual space where all ngoma sessions are

held, as well as "calling down ancestors"; (b) kitchen; (c) bedroom;

(d) storage room; (e) backyard; (f) subrenter shelter; (g) water tap, toilet;

(h) profane public space where "coming out" is held and where darkness

of pollution is "thrown away."

4. Ukunqula: Hulle wil meet wat makeer vandag? Kaffirdans. You want to know what's happening here today? It's a Kaffir dance! Let darkness be replaced by light.

Ngoma: Ndiyamthenda u Jesu; waklulula umoy a wam . I love Jesus, he set free my soul.

5. Ukunqula : Let darkness be replaced by light. Camagusha . I thank being welcome in this home, camagu . I was coronated in this home, and the isidlokolo bushy hat was given to me here.

1.

Young women and mothers of the lineage in procession, during Nkita rite in

Kongo-Ntandu society, western Zaire. Photo archive, Institut des Musées Nationaux

du Zaire.

2.

Diversity of ngoma drums

from the Congo Basin, Zaire:

(a)

with face of Mbuolo healing

spirit, Yaka, Southwestern

Zaire, Institut des Musees

National duZaire (IMNZ)

71.138.1 (59 cm. tall, 28 cm. wide);

(e)

RMCA 8977, Kusu, Maniema, 65 x 36

cm., before 1902 (Boone VI/2 "ngoma");

(f)

RMCA 48.20.107, Hungana,

Southwestern Zaire, 98 x 33 cm.,

before 1948 (Boone XIII/10);

(b)

Tshokwe-Lunda, Kasai,

IMNZ 71.22.13 (53 cm. tall);

from the collections of the

Royal Museum of Central

Africa, Tervuren (RMCA)

and published in Olga Boone,

Les tambours du Congo belge

et du Ruanda-Urundi, 1951;

(c)

RMCA 38828, Luluwa, Kasai,

52 x 35cm., collected 1939

(Boone plate VIII/34, "ngoma");

(d)

RMCA 31696, Tabwa,

Southeast Zaire, 28 x 27 cm.,

prior to 1882–1885

(Boone VI/12, "ngoma");

(g)

RMCA 27729, Lele, Kasai,

98 x 28 cm., before 1924

(Boone XXXVIII/5);

(h)

RMCA 37955, Hutu, Rutshuru, Kivu, 83 x 41 cm.

(Boone XXVII/7, "ingoma" or "impuruzu"), the

thong-tied drum beaten with stick shown here,

typical of northern forest and West African

region, but with form and name of "ngoma" area.

The faced drums articulate visually the idea of

the spirit-rhythm in ngoma. Photographs c—h

courtesy Section of Ethnography, Royal Museum

of Central Africa, 3080 TERVUREN, Belgium.

3.

Kishi Nzembela, of Kinshasa, Zaire, before painting of her late daughter

Janet, for whom she is a medium in Bilumbu, a ritual of Luba origin. Photo

by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

4.

Kishi Nzembela, a Catholic, stands before this painting of Jesus in her healing

chapel in her home compound in Kinshasa. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

5.

Pregnant woman "in seclusion" as part of reproduction enhancing ngoma

among the Chokwe of Zaire, Southern Savanna. This is comparable to ngoma

Mpombo in the South Kasai. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1959.

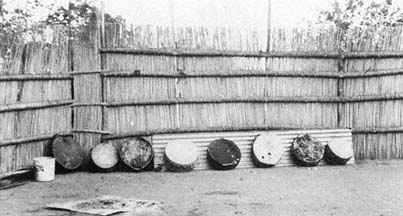

6.

At Betani, the diviners' college, eight tigomene drums of cowhide over seg-

ments of oil drums lie in the sun to tighten the hide for the next performance.

They will be used in mediumistic takoza divination ceremonies to reveal the

causes of distress for clients. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

7.

Tanzanian mganga Botoli Laie of Dar es Salaam demonstrates and displays paraphernalia for ngoma Mbungi:

five ngoma drums, two wooden double gongs, and medicine basket. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1983.

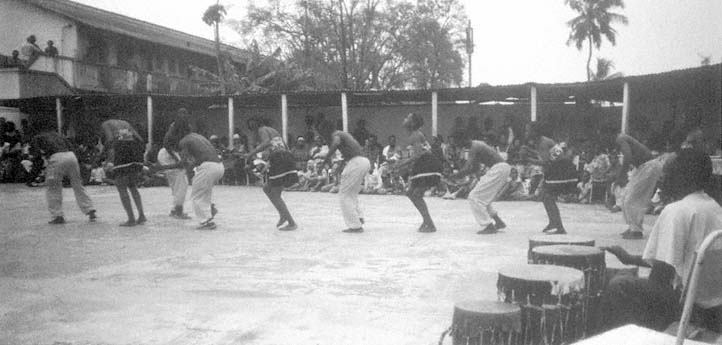

8.

An example of ngoma as secularized entertainment, performed by the Baraguma ngoma troupe of Bagamoyo, here doing the Sindimba dance

at the Almana nightclub in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Instruments include ngoma, other drums, and xylophone. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1983.

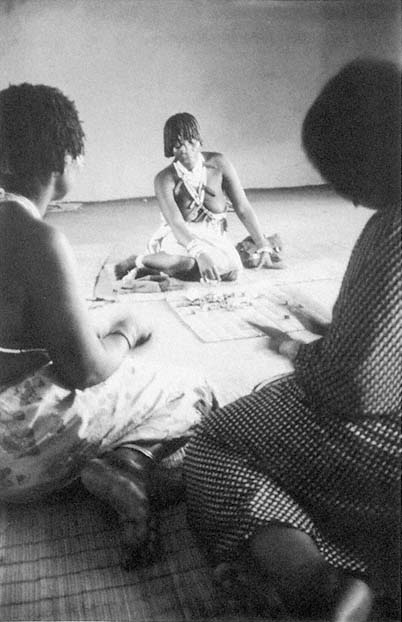

9.

enior novice in Ida Mabuza's college in Betani, Swaziland, performs pengula

bone-throwing divination, widespread in Southern Africa, before a client (right)

and a colleague (left) who indicates agreement or disagreement with each

declaration by the diviner. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

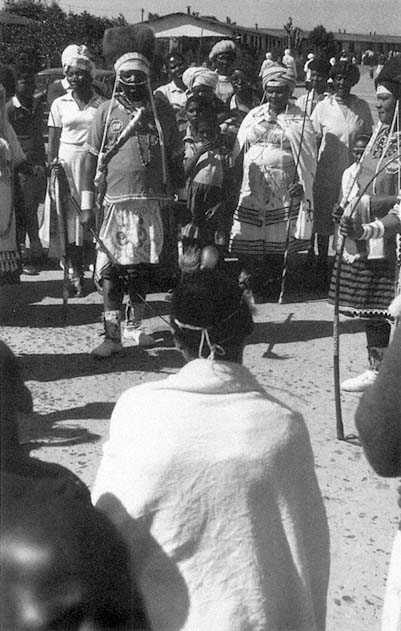

10.

A group of novices (amakwetha ) in white performing an ngoma on the street in Guguleto township, South Africa,

at the time of a "washing of the beads" purification for igqira Adelheid Ndika. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

11.

Cowhide over oil drum is here used in an ngoma session in Guguleto, Cape Town,

South Africa. It is drummed by a novice (nkwetha) who has her head bound with

two strands of white beads to indicate that she is "in the white." She is accompanied

by a hand-clapping noninitiate. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

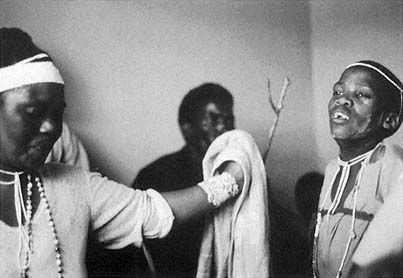

12.

Two novices (amakwetha) participate in ngoma session in Guguleto, Cape Town.

They are part of a close circle of novices who are "presenting themselves" in

call-and-response performance. The script of this event is given in chapter 5.

Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

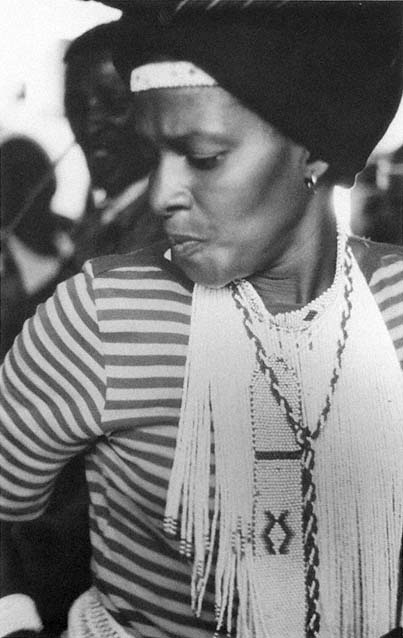

13.

Ngoma session presented in chapter 5 was led by this woman, a just-graduated

igqira (healer) whose manner of leading the others out, of dancing, and of

bringing the participants together was as striking as is her composure in the

picture. The beadwork is the beginning of her igqira costume, which began

with a few strands of white beads when she was a novice and will flower into

a colorful full costume. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

14.

A "white" novice serenely watches others in

ngoma performance after having presented

herself to others in evocation, prayer, song,

and dance. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

15. Preparing to "throw out the darkness,"

the pollution of death of a novice's kinsman.

Igqira Golden Majola distributes tobacco to

his novices, which they will throw into the

waters of the Indian Ocean near Cape Town

to the accompaniment of a singing and drumming

ngoma. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

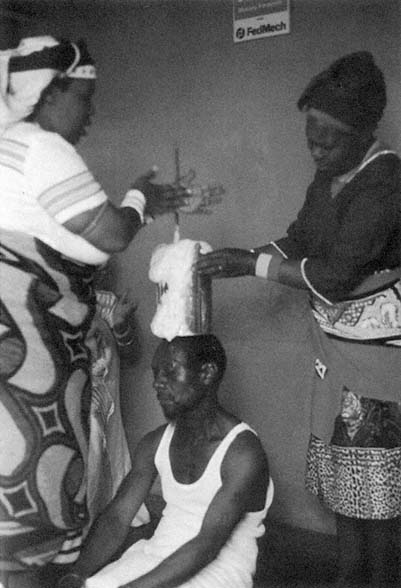

16. Amagqira Adelheid Ndika (left) and helper (right) stir the ubulau medicine of entry

into "the white" at the outset of the sufferer's novitiate. Photo by, J. M. Janzen, 1982.

17. Later, after the goat sacrifice and the all-night ngoma, the opening

phase of ngoma initiation is concluded with ngoma sessions on the street of

Guguleto, a black township near Cape Town. The "white" novice is seated

in the foreground while fully qualified amagqira take turns encouraging him

with song-dance ngoma. Photo by J. M. Janzen, 1982.

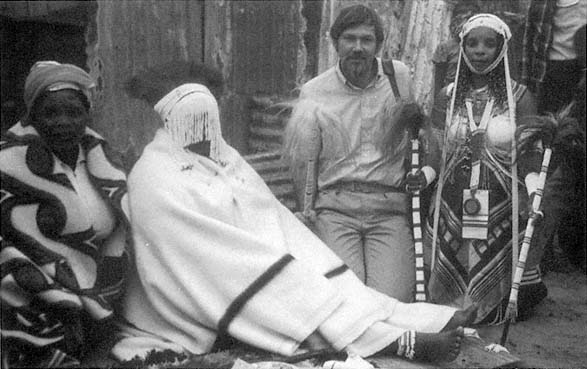

18.

The author kneeling between the graduating still-veiled novice and her kinswoman (left) and her igqira healer (right),

in Guguleto township. Photo by Reinhild Janzen, 1982.

Ngoma : I love Jesus, he set free my soul.

6. Ukunqula : Mzala, I thank what you've done, saying sorry after "sinning," consulting those above you.

Ngoma : I love Jesus, he set free my soul.

7. Ukunqula : We came to uncover the wound, and thereafter take some oil and anoint it. I, too, came to say: Let the wound be healed. The amagqira have spoken well.

Ngoma : I love Jesus, he set free my soul.

The basic call-and-response structure of the ukunqula/ngoma pattern is enriched by a rhythm between speaking and singing. Afrikaans, English, Xhosa, Zulu, and Swazi evocations and songs in these two sessions are a particularly poignant reminder of the cleavages and cosmopolitan diversity of South African society. Especially touching are the exchanges in Afrikaans (#3, #4) that may have been prompted by my presence with several members of my family. One of the senior igqira in evocation number 3 asks the others to tell "why we're here." That is followed by an ngoma in Afrikaans: "What's happening here?" The next ukunquia (#4) responds that it's a kaffirdans . This demonstrates the power of the medium to absorb the condescending attitude of white South Africa toward an African institution. The exchange is, however, intended to be ironic. Ukunqula number 2 also touches on the role of ngoma in helping these amagqira deal with the racial tension in their society. This woman was a domestic worker in a white home, and she complained to us of her low wages for long, hard working hours despite many years of seniority. She used the ngoma session to tell the others, and her ancestors, that this is what made her "on edge," or spiritually "sharp."

The repetition of the ngoma "I love Jesus ..." from Zionist singing, demonstrates the influence of Christianity, but it also suggests that it is difficult to draw a line separating "African" from "Christian" reference points. However, ngomas 1, 2, and 7 are in a more conventional idiom.

After shaking off the isimnyama , pollution, as a result of the death, and singing-praying for the igqira, the second ngoma session follows for the novices. A just-graduated, fully qualified igqira (the woman in the blue and black striped sweater, plate 13) leads this session. (Plates 10, 11, and 12 portray this event.) She opens with a song-dance.

Ngoma: Simonwoya . We have spirit ...

8. Ukunqula [by a boy novice]: Ka Ngwane [ancestors], hear me.

Ngoma: Mombeleleni, unonkala, ngasemlanieni . Sing and clap for the crab next to the river.

Ngoma: He Majola [clan name], phuma e jele . Majola, come out of jail. Ndinendabe zonzi wakho . I have news of your house. (See fig. 10.)

[One of the persons in the circle points to another who is sick, a novice.] We are giving [the song, ngoma] over to you mother, camagu .

Ngoma : ... eluhambeni . ... in a trip [inaudible].

9. Ukunqula : I ask for protection from my people [ancestors], the Radebes and the Mtinikulus.

Ngoma : [call] Akulalwa ezweni akulalwa ; [response] akulalwa akulalwa ezweni . ...

Ngoma: He Majola phuma entelakweni, ndinendaba zonzi wakho . Majola come out of confinement (lit. "the pot"), I have news of your household. Camagu!

Ngoma : Hey Majola, come out, I have news of your household.

10. Ukunqula : Let darkness be replaced by light. I call on my ancestors. This igqira was handed me by a parent while living. I take after my grandmother, and use one of the eyezeni medicines. I resemble an igqira of igqiras, a truly authentic one. The white bones over which death lies, I approached them with my back turned to them, that they not be resentful of me. May the drug be revealed to me, so that as an igqira I may be able to say the truth after kneeling before my clients.

Ngoma: Khawuhibe igqira . Go, go igqira.

11. Ukunqula : Since I almost left this ceremony without coming forth to say something, I might fall sick after leaving this house. May I sing.

Figure 10.

Spatial layout of "doing ngoma" in living room of home depicted

in figure 9; (a) all participants in living room; (b) circle of amakwetha

(novices); (c) fully qualified igqira (healer) who leads session; actors in the

ritual unit once session has begun: (d) in left-hand scheme, novice presents

ukunqula ; (e) other novice or leader responds to self-presentation, and

leads in song-dance, as shown in right-hand scheme.

Ngoma: Ndine thumba lam lokuthandaza . I have my time to pray.

Ndinendawo yam yokuthandaza . I have my place to pray.

12. Ukunqula: Camagusha! Let us remember what we are here for. To ukublamba , purification. I have very little with me. [Response] Camagu. Let the darkness be replaced by light! [Response] Camagu . I pray for a drug, that it may do its work. May it be there, as far as the caves, the river, from where it comes, and where its roots are ground on a stone to make medicine of it. I am also here to pray to God. May this home of the Makwayis have the darkness replaced by light.

Ngoma: Andimanto esandleni, ndize kanye Nkosi. Sendondele ekrusini, ekubethelweni . I have nothing at hand, I come once Lord ...

13. Ukunqula : When I'm here, presenting myself, I think back to my mother's home, at the KwaNguni, and the way they said, "Let darkness be replaced by light." Ndiyanqula ndiyathendaza, camagwini ? [Response] Camagu . I admit that I take pills when I come to a ceremony [inthlombe ] because it makes me sick. May darkness be replaced by light. My people should not worry that I'm doing

this ukunqul presentation. I'll lead in my song and then hand the ngoma over.

Ngoma: Andiyoyiki le ntwaza na ingangani . I am not afraid of this girl who is as big as myself. [Response] Camagu .

14. Ukunqula : I am hard-pressed by rental fees and many other things. I had to take from my children, asked them to give me some soap, for the young women here to smell good.

Ngoma : Blessed be the name of the Lord [in English].

Ngoma: Yomelelani kunzima emblabeni . Be strong because it's hard here on earth.

15. Ukunqula : I come from afar. My home is in Swaziland, and I'm a visitor. I call on my ancestors.

Ngoma : [call] Unwoya wam ; [response] wankbulul'umoya wam . My spirit, he set my spirit free.

Ngoma: Ndize kuwe, undincede . I am coming to you Lord for help.

Ngoma: Sicel'i camagu . We are requesting a camagu.

16. Ukunqula : I call upon my ancestors to let darkness be replaced by light. I am glad that the darkness that has been hanging over here could be removed, that broken hearts have been consoled. I thank all of God's children present, in the name and authority of Jesus. Hallelujah, might God give us power. May Jesus give the woman Maradebe power. Things are as they are, the wearing of white beads [novices who are initiated], because there is no peace in the world. Hallelujah, beloved ones, may God bless you.

Ngoma: Themba lam ngu Yesu, ndozimele ngeye . My hope is Jesus, I'll hide in him.

17. Ukunqula : I wish to be a sincere, honest igqira. If I can't diagnose something, I'll kneel down and pray in order to tell the truth. I want to stand atop of Table Mountain and be light to the people. May the darkness be replaced by light!

The spoken calls (ukunqula ) and sung responses (ngoma), with drum and dance accompaniment, demonstrate the complex basis of this institution. There is a keen desire on the part of these novices (amak-

wetha) to be in touch with each other, as they put it, to camagusha . The phrases "let's camagusha " or the call "camagu! " followed by the response camagusha indicates before each ngoma unit a kind of ritual positioning to follow through. This call announces, in effect, "let's do an exchange," or "we have heard," "we have agreed." These verbal signals are important as rhetorical framing devices in the ngoma work at hand.

There is also evidence of deliberately handing the ngoma around, as it were, "being it." In set number 8 someone, it is not clear who, hands the song over to another woman.

The content of the individual declarations and songs varies widely, the former for the most part relating to the lives of particular individuals, their call, sickness experience, environment, their aspirations, whereas the latter, the songs, are more culturally standardized. A number of ukunqula evocations call on ancestors for help and solace. We see from the names mentioned that this is a varied group of novices from across Southern Africa. Clan names such as Ka Ngwane from the Eastern Transvaal (#8), Radebe and Mtinikulu (#9), the generic KwaNguni (#13) are mentioned. One says she is from Swaziland. The ancestors are invoked in a general sense here, which differs from identification with particular ancestors in other regions of Central and Southern Africa (e.g., Fry among the Zezuru, or Turner among the Ndembu). There is also indirect and direct reference to natural domains of land and water and to mediators across these domains. The young boy (#8), following his ukunqula , sings out the "crab song" and others join in. This is a commonly heard ngoma both in Southern Africa and elsewhere (the term nkala for crab is very widespread, as is the reference to the crab as a mediator). The crab burrows in the beach sand and scurries into the water when discovered. It is the perfect natural reference for a spiritual metaphor bridging land, the domain of humans, with water, the domain of ancestors and spirits. Similarly, there is reference to plants and drugs (e.g., #12) found in caves and along rivers, mediatory zones, that are used to enhance the ngoma process of "coming out" and "sharing" and "presenting" oneself.

Most of the novices express a concern for articulating their inner conflicts, getting their words out. Songs in numbers 8 and 9 mention a Majola who is implored to "come out of his confinement"—literally a pot—because they have news to share with him. This image of a person being in a jail, or a prison, or a "pot," is an intriguing one for the person who is trying to clarify his situation. Another image common in this

occasion was that of "replacing darkness with light," being able to "see" clearly.

Some of the ukunqula self-presentations have to do with personal problems. In number 10 the novice talks of her call from her grandmother and asks that she be able to follow in her steps as an igqira. In number 11, the novice feels compelled to share so that she won't become sick. The novice in number 12 prays for a medicine that will help her clarify her situation. Novice number 13 admits that she takes medicine prior to the sessions because they make her sick. In number 14, the singer confesses that she is so poor that she took from her children to be able to bring something to the sharing session. Another, in number 16, laments that there are so many lgqira/ngoma novices because things are so hard, because there is no peace in the world. Several seem to be already thinking ahead to when they will be igqira. Novice number 10 prays that she will have effective medicines revealed to her by her grandmother. Novice number 16 prays that another woman may have power. Novice number 17 wishes to stand atop Table Mountain—the highest, most prominent point in the Cape—and be a shining light to her people.

References to God, to Jesus, and to the ancestors suggest that there is no dividing line in the minds of these people between what is "African" and what is "Christian." In fact, many of them have been in contact with the church and even continue to be members, but they are now participants in ngoma to come to terms with their sickness, their situation, and their ukutwasa , "call."

Common Songs And Personal Song In Ngoma Narrative Tradition

The distinction between the therapeutic song and the coming-out song suggests that within the complex symbol "ngoma" there are at least two levels of narrative or performative understanding. The first is the importance of song-dance in defining and coming to terms with the suffering; the second is the importance of moving the sufferer toward a formulation of his or her own personal articulation of that condition.

In Victor Turner's account of Chihamba, a cult of affliction devoted to Kavula, the White Spirit, a doctor named Lambakasa "sings an ngoma " to Kavula on behalf of another woman asking to be relieved from barrenness:

Completely white is that white clay

You yourself grandparent [nkaka ]

All of you, you Nyamakang'a

All of you, our dead.

Today if you are making this person sick

Today we will sing your drum

This person must become strong.

Completely white is that white clay. (Turner 1975:63)

This appears to be a generic ngoma, not Lambakasa's special song. Yet it fits the format of intercession of one ngoma participant for another, seen already in the case of the young Cape Town novice who could barely do his ngoma, or of the senior healer whose sister sang of her grief at the death of their mother, or of the participant who turned the song over to a particular woman who was very sick. This format is the quintessential act in ngoma, for it bonds the singer to the one being sung to, and shows the second how, when he recovers, he may begin to reformulate his own self with a creative new song.

Ngoma may take another form in which the individual begins to present self in a more active and articulate manner. This leads to the special personal song. An example of this is found in the work of psychoanalysts Vera Buhrman and Nqaba Gqomfa, who have studied Xhosa healing in the Transkei, South Africa. Every igqira (sangoma) and trainee has a personal special song that "came to him" during sickness and training (1981:300). Mrs. T., an igqira who is the main figure in the article, was healed by and trained with her igqira husband. She dreamed her song at the beginning of her sickness, when she was twasa:

Ho, here comes an animal,

It is clapping for me.

This song, like many among the amagqira, represents figures of the water or the forest ancestors, thus having an outer cosmological linkage. Further dimensions of Mrs. T's song, or songs, demonstrate her inner self-image, and the immediate events in her life, most recently a death in her family:

I am sick, I am sick.

News is bad about me in this location

Things are bad with me,

I am living by prayer.

All things have gone wrong at my place.

I am going.

Things have gone wrong at my place. (1981:309–310)

Her husband's "special song" dwells on his medium, a horselike figure that he calls Vumani:

Here comes Vumani,

I divine with him,

My horse of news.

I will die calling

Ho! It is coming!

Ho! My horse of news

Is coming.

Vumani. (1981:303)

An example of a strong, fully developed song comes from the Lemba order of early twentieth-century inland Kongo society. Here entire polygynous households were initiated to Lemba following affliction or draft by the household head. Lemba's characteristic sickness afflicted this mercantile elite, striking them with fear of the envy of their subordinates and the urge to redistribute their wealth to their lineage communities. The Lemba initiatory treatment created especially consecrated polygynous households that served as nodes on the regional fabric of alliances and routes through and over which the caravans moved on their way to and from the ocean and the big market at Mpumbu above the rapids on the Zaire River. One of the few personal Lemba songs that has survived follows:

That which comes from the sun

the sun takes away.

That which comes from the moon

the moon takes away.

Father Lemba,

He gendered me, he raised me.

Praise the earth,

praise the sky.

For I have been enhanced,

I have gone far,

From far I have brought [Lemba] back.

The initiate Lemba couple has taken a pilgrimage into contact with the ancestors to bring back its Lemba insignia. It is also a symbolic pilgrimage song, declaring successful emergence into full Lemba status. A further verse of the song addresses the sufferers this successful therapist works with.

Search in the ranks

of the patrifilial children

of your clan.

KoKoKo [of the drum] ... Ko! [response of drum]

Will you gain Lemba? E [yes] Lemba!

The presiding healer refers to the source of initiatory revenue the client may bring, and the lineages of the matriclan's sons in whose ranks one may find preferred marriage partners to enhance community stability. Addressing the spirit, the healer sings:

Let go of the sufferer so he may be healed,

He will bring goods accordingly

Thereby offering a gift to your priests. (Janzen 1982:120–121)

A final example, from historic Sukuma in western Tanzania, from ngoma Ndono, shows that the ngoma song can take a collective, almost national turn. Here, a Christianized song from the time of World War I laments the drought that is raging and draws some wider implications.

We failed in our duty to Jesus the redeemer.

Our God, he is cross and sends no rain.

We see the clouds but they move away.

God hides the water and lets us die,

even the child in the womb of the mother.

What is our crime, O God?

Men arrived who taught us lies,

not to make the right sacrifices.

All countries are sad;

everywhere the sun is shining with such force.

Our God is very cross about adultery, witchcraft, lies, and

the crimes of theft.

The Mtemi Mkondo of Bulima has a good name,

but he does not succeed in making rain.

I hear that far toward lake Victoria there is rain.

The rain there moves stones,

it drives them quickly in front of it along the ground.

O Mother, wait, I shall sit on a log and

look at the world to see from where the rain comes.

Where is my father to teach me?

I am alone.

Though the ax of the rainmaker Migoma can be noticed,

I am alone, but not afraid. (Cory n.d. a )

The study of songs such as these in African healing has not come very far, since most scholars who have looked at them have concentrated on lyrics or on nonverbal symbols. They have not usually associated the content of these songs with social and cultural concepts. Yet

the distinction between common and personal song appears to be very widespread in ngoma-type rituals. The significance and the role of self-presentation, or of others helping the sufferer learn to articulate self and ultimately compose his or her own song or song repertoire, have barely been outlined in field studies and in scholarship.

The Structure Of Ngoma Therapeutic Communication

One way of comprehending the place of ngoma song in African healing is to take seriously the reference to text, texture, and context, and to look not only at the content of the songs but at the structure of these communications. The underlying and most pervasive structure of ngoma is the call-and-response pattern that is common in most African music. This is true not only of the songs, but of the very structure of the music and the ritual itself. There are numerous variations on this theme: sufferer and healer; sufferers among themselves; healers among themselves; sufferer, healer, and others; elements of sufferer's kin group; and spirits and humans. Since little collected therapeutic song material gives the relational context clearly, we need here to depend on the examples available from across the ngoma region.

The Western Cape example of "doing ngoma" offers a ready illustration of the call-and-response motif of song. The invocation, spoken, is followed by a song that is intoned by the speaker. The surrounding individuals join in with song. There are further amplifications of the call-response rhythm. There is the dialectic of speaking and singing. Within the singing there may be a call-and-response pattern. The sets of invocation (ukunqula ) and song-dance (ngoma) are referred to by the set call "Camugwini ?" and the response "Camagusba! " These two applications of the common verb "to agree," or "to have consensus, or affirm," pave the way for a well-understood routine that brings a sufferer into the group, sets him or her up to offer a few thoughts or concerns, and for the others to respond to them in an affirming, supporting manner. Throughout all of this, instrumental accompaniment is limited to the song-dance, and follows the vocalized, danced portion of the set. This is in keeping, everywhere, with the pattern of instruments becoming a secondary or tertiary voice in the sequence of voices entering in. According to Simha Arom's massive work Polyphonies et polyrythmies instrumentales d'Afrique centrale (1985), this feature is basic to musical styles across Africa. It is the foundation upon which

the unique features of polyrhythmic and polyphonic patterns are built (see fig. 11a).

A more elaborate pattern of different voices is illustrated in the account of Lemba songs offered above. Here, senior priests and priestesses, the novice priest and priestesses, and the patrifilial children of the novice priest exchanged turns leading their songs in a "graduation" rite (Janzen 1982:114–121). These songs are intoned with the verbal call "Ko-ko-ko?" (suggestive of the drums) and the response "Ko!" Then the lead singer opens with a phrase such as "Will you gain Lemba?" and the chorus responds with "Yes—Lemba!" This is followed by the body of the song-dance performance of each particular song, with its recurrent internal call-and-response pattern.

A further, larger structure reflects the parties present in the rite. Throughout the event, the progression of lead singers is the following: (1) sponsoring healer or Lemba Father; (2) the other Lemba priests who are present at the event (sometimes the Lemba priestesses have a separate song); (3) the patrifilial "children" or offspring of the novice (that is, the offspring of males of his matriclan—a classificatory support group); (4) finally, the novice, after he and his wives have completed their initiations (see fig. 11b).

In the communication pattern of song in which divination is done, an even more complex exchange emerges at times. This can come in two ways. The first is in the presence of a third party who affirms or negates the interpretation of the diviner-healer; the second comes in those cases in which the diviner acts as a medium for a spirit. In Southern Africa the "third party," either an assistant to the diviner or a kin or friend representing the client-sufferer, responds to the divinatory interpretation of the diviner. After each utterance of the diviner, the third party intones "I agree" (si ya vuma ) or "I do not agree." In the first case the diviner will continue the course of analysis of the case until reaching a conclusion. In the latter, the diviner will back up and try another track of analysis or will stop to discuss the case with the client. However, in Southern Africa and elsewhere, the diviner is often expected to establish the truth through a variety of convincing means, mechanistic or inspirational. Divination is not an empirical science based on questioning and the study of empirical evidence; it is held to be a mystical art, based on clairvoyant knowledge and wisdom. Thus, at the end of the session, there is agreement.[2]

When this clairvoyance is expressed in mediumistic form with the spirit invading and speaking through the diviner, in a sense the spirit

Figure 11.

(a) The structure and sequence of voices and instrumentation in

ngoma song, common to African music more widely; (b) the relationship

of "roles" or "parts" in a documented ngoma event in North Kongo in the

early twentieth century (Janzen 1982:106–124).

is the third party along with the diviner and the client-sufferer. In the ethos of possession divining, it is not appropriate to disagree with the spirit. One may not understand the spirit, but it is always right. Therefore the diviner becomes the third party, interpreting the utterances of the spirit as they are channeled through him or her, much as the diviner interprets the bones in Southern Africa, or the Ngombo basket objects on the Southern Savanna, or the shells of the Ifa oracle.

The combination of multiple communicative dimensions of vocal, visual, instrumental, and spatial and social domains enriches the overall "text" in ngoma, allowing it to articulate the complexity and contradictions of human experience. This process is enhanced by the addition of interpreters or the addition of points to the communicative structure (fig. 12) and of music to the communication, all of which we may speak of as "ritualization."

In several anthropological definitions of ritual inspired by communications theory (e.g., Leach 1966, 1976; Bateson 1958, 1972) the essence of ritualization is the process of adding channels or mediums of expression to a discourse so that there may be multiple, or redundant,

Figure 12.

Modes of mediation in ngoma communication. These variations

model most of the cases presented in this work in terms of structures

between subjects or "players." Setting (a) shows a common clinical setting

with a therapy manager mediating between healer and sufferer. Divination

usually offers two types of structures, (b) and (c), in which the technique or

the shade/spirit become the message mode between healer and sufferer-

client. A more elaborate model emerges, (d) and (e), in which there is an

interpreter for the diviner and the spirit or technique (as in Nguni divining

where someone intervenes to "agree" or "disagree" on behalf of the client.

This model also applies to "doing ngoma" (e) in which there is a session

leader who mediates between spirits and novices, and a particular novice

at a given moment and the others who respond in ngoma.

levels of communication. Thus, in the example cited above, instrumentation would both repeat, and enhance, the primary level of vocal communication. For Bateson and Leach, ritualization occurs because of a "block" or "static" in primary channels of communication and behavior. Redundancy helps to overcome or bypass these blockages. This is not far from Turner's (1968) approach to ritual, which it is based more on the importance of sign and symbol. In this perspective, ritual is simply the greater degree of "density" in the meaning attached to par-

ticular sign referents. Ritual acts out relationships and meanings so as to heighten emotion and to articulate contradictory sentiments. These authors are not, however, overly concerned with the role of music in ritualization, although their theories do not contradict the focus upon music that is ultimately required to understand Central and Southern African ngoma.

Of Music and Ritual in Ngoma

Mahamoud Kingiri-ngiri, the Sufi Muslim mganga (healer) of Dar es Salaam who was introduced in chapter 1, rejected the use of ngoma in his healing work on the grounds that it was merely "happiness." Isa Hassan, who is also Muslim, utilizes ngoma because it is an essential method of getting the patient to "talk." Ngoma, especially the drumming, "heightens emotions." The theory behind this theme will be taken up in the next chapter, in which we explore "how ngoma works." Here I introduce the character and role of music in ngoma therapeutic ritualization.

A frequently mentioned feature of musical ritualization in this tradition is the "distinctive rhythmic pattern" of each ngoma. John Blacking, who has studied the music of the Venda people, traces this feature to the place of rhythm in the very distinction between song (u imba ) and speech (u amba ) (1973:27). As this distinction is also present in the KiKongo language in Western Bantu—singing being kuyimba , speech kukamba —we may assume it to be another very widespread Bantu language feature beneath therapeutic ritual. For the Venda, as for other Central African societies, ngoma and related therapeutic rites and techniques are designated by their distinctive rhythms. Of the nyimbo dza dzingoma , Blacking notes that these "songs for special rites accompany certain ordeals that the novices must undergo when they are in the second stage of initiation. Each one has a distinctive rhythmic pattern" (1973:41).[3] In Tanzania, Isa Hassan and other waganga and music experts also point to the association of spirits in ngoma and distinctive rhythms. Music, with the assistance of medicines, brings out the speech in the sufferer, which then indicates to the presiding mganga which spirit must be dealt with. For Botoli Laie, a mganga from Kilwa in Tanzania, specific instruments play distinctive rhythms appropriate to each spirit. This degree of specificity between spirit and rhythm, as well as the dance, is present as well in loa possession in Haiti (Cour-

lander 1960:21), particularly in the Central and West African originating spirits.

We should be slow, however, to make a necessary connection between particular rhythms, instruments, and dances and spirits across the full gamut of African expression. As we have already noted, trance is not necessarily a corollary of the spirit or shade etiological hypothesis. In the Western Bantu Nkita society, the entire lineage is caught up in doing the rite. Its initiation is prompted by the sickness or death of infants and mothers in the matrilineage or by disputes at the time of protracted segmentation events. The "therapy" also entails restoring ancestral legitimacy in the lineage fragments. Even in settings such as the Western Cape recounted earlier in this chapter, the tightly regimented ngoma song-dance sessions do not prompt trance behavior, nor do there appear to be distinctive rhythms with the particular ancestral figures mentioned in the self-presentations and the songs. Gilbert Rouget's well-known work Music and Trance is based on the assumption that music is widely associated with trance, in some places triggering it, and in other settings calming it (1985:xvii). The relationship between the two is thus more complex than the reductionist arguments proposed by authors such as Neher (1962), Needham (1967), Huxley (1967), and others who suggest that percussion, drumming, or related pounding rhythmic music, by its intrinsic nature, stimulates or generates dissociative behavior.

These reductionistic theories of musical rhythm and trance behavior are very attractive in certain settings in Central and Southern Africa where trance occurs in connection with strong drumming. Attendants of a seance in which trance is accompanied by the participants' use of shakers and several types of drums, including the high pitched ngoma, with rhythm upon rhythm added to achieve the unique polyrhythmic effect that African music is so well known for, must in their "gut" believe in the theory of the neurological inducement of trance through rhythm. The effect of polyrhythmic percussion is not only the hammering, driving of the basic beats, which are like call-and-response patterns in conversation with each other, but the "metronome sense" (Chernoff 1979:49) of the "off beat" and the "hidden beat" that pulsates as a basic driving force beneath the surface (Thompson 1983:xiii). The supposition that this hidden beat sets up sympathetic echoes with the brain's alpha waves, which are at a comparable rhythm, seems quite plausible.

The problem, again, is that not all trance is touched off by strong

rhythmic music—indeed, some is touched off by no music at all—and some strong polyrhythmic music when played masterfully does not induce trance. If there is a statistical prevalence of trance or possession behavior in the ngoma region in association with polyrhythmic music, with drumming, especially ngoma drums, despite the tempting reductionist hypothesis, the evidence and the logic of the case require us to conclude that it is a culturally mediated association.

Such a conclusion suggests that trance may be an analogy or a metaphor for the interpretation of life's experience but is not a driving or determining force that invariably shapes the course of sickness and healing.

Conclusion

"Doing ngoma" is the central feature of the institution we have called ngoma throughout this work; it is the ritual unit that defines the institution. Doing ngoma has been illustrated in this chapter by a Cape Town event in 1982, but it could have been equally well illustrated by events from throughout the wider region where, it seems, a great similarity of form prevails. This ngoma unit is structured around the call-and-response paradigm of communication, with spoken call often being echoed or answered by sung and danced response and the accompaniment of instruments. This communicative structure is the context within which the meaning of individual lives, among the ngoma practitioners, is articulated and where these individuals are urged to create a song of their own. Of course, there are counseling sessions and other types of conferrals between these semipublic ngoma gatherings that may occur whenever ngoma adherents meet. But it is the ngoma song-dance presented here that is the "minimal constituent unit" of the entire ngoma process.

Western scholarship has not known exactly how to categorize this unit, as was the case with the larger institution. Is "doing ngoma" music, or is it song, dance, or group therapy? Is it worship? In the theoretical push to identify the uniqueness of the institution, I have reserved judgment on this score by introducing the core notion as a translation of the indigenous name, "doing ngoma." Some of the principles of "ritualization" seem to apply to the manner in which ngoma is done and when it is done. More will be said in the next chapter about the amplification of messages and the role of metaphors within the

song-dance communication, especially on the role of spirits in these communications.

A close look at "doing ngoma" reveals that it is the format and the setting in which highly individualistic perceptions are brought into the mirror of social reflection and subjected to reinforcement, repetition, and reaffirmation. The source of all the texts, dances, and rhythms is this individualized yet collective session in which the participant-sufferer-performer is urged to "come out of his prison" to full self-expression.