Preferred Citation: Lingis, Alphonso. Abuses. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1994 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3779n8sd/

| AbusesAlphonso LingisUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1994 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Lingis, Alphonso. Abuses. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1994 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3779n8sd/

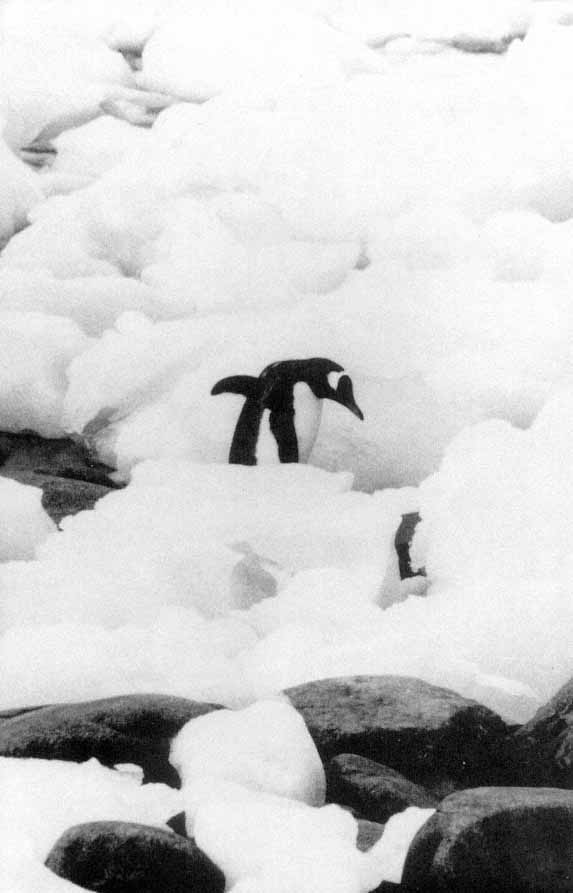

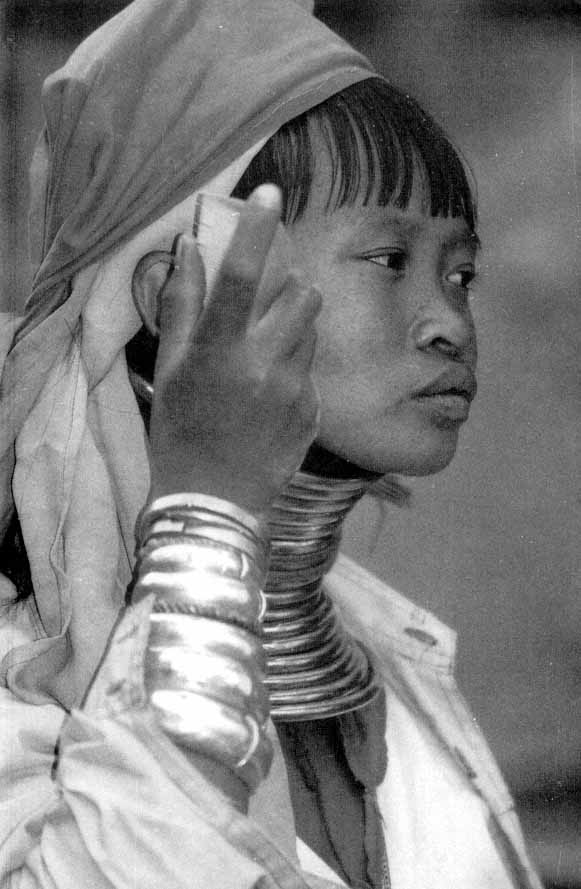

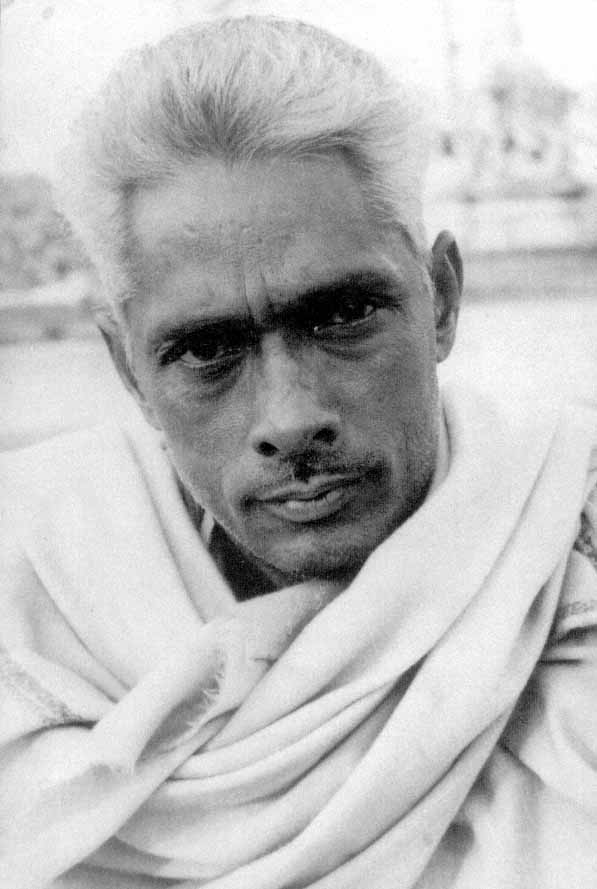

These were letters written to friends, from places I found myself for months at a time, about encounters that moved me and troubled me. Letters from Mexico, Cuba, Peru, the Philippines, Nicaragua, Antarctica, Brazil, France, Thailand, India, Bali, Bangladesh, Guatemala.

The letters were almost never answered, maybe never read. Nowadays people only write letters to record requests, transactions, and detailed explanations, or to send brief greetings; when they want to make personal contact, they telephone. Conversation by telephone communicates with the tone and warmth of the human voice, but what moved one deeply can only be shared through language when one has found the right words. Finding the right words takes time, and the one to whom they are addressed is no longer the one you thought he or she was when you wrote. One sends one's letters to an address he or she has left

It is hard to share something only with words on a silent page. As the places and encounters reverberated in my heart, I found again and again they had not been said with the right words. What I wrote about them finally became too long to send to anyone. I will again find they have not been said with the right words.

To whom, gathered together in this book, are these pages now being addressed? To friends whose names and addresses I do not know. To you, in Mexico, Cuba, Peru, the Philippines, Nicaragua, Antarctica, Brazil, France, Thailand, India, Bali, Bangladesh, Guatemala, and

in places I have never or not yet visited, you who are moved and troubled by what and by whom you encounter there.

It is you who teach me the right words. To find the right words is not only to find the words that convey the tone, the pacing, and the progression of the event; it is also to find the words that communicate to others because they are the words and forms of speech of those others. And though I do not know your names or addresses, these writings have no other purpose than to learn one day from your words the events and encounters that have moved and troubled you. I do call you friends, because it has long seemed to me that a friendship where one does not teach one another becomes shallow and meaningless. Everyone who, while wandering along the shore of whatever continent or island, has found a letter put in a bottle and cast into the sea, has found a friend.

These writings also became no longer my letters. I found myself only trying to speak for others, others greeted only with passionate kisses of parting.

What I wrote was how places and events spoke to me. What persons my nation and my culture have made enemies said to me. What people my nation and my culture have conquered and silenced said to me with their mute bodies. What in sordid places their bodies beautiful and sublime beyond beautiful said to me. What their animal passions said to me. What persons who were dying and had nothing to say about the unknowable they were not advancing but drifting toward said to me by the endurance with which they bore this last journey. What ruined temples and departed gods said to me. I understood that what they said to me they were saying to you.

When the other is there and able to speak himself or herself, he or she listens to the thoughts one formulates for him or her, and assents to them or contests them or withdraws from them into the silence from which he or she came. One only speaks for others when they are silent or silenced. And to speak for others is to silence oneself.

One will say that the philosophical reflections I elaborated were my own. Did not Nietzsche say that philosophy is the most spiritual form of the will to power? It is true that I studied philosophy books, and teach them. Philosophy is abstract and universal speech. It is speech that is not clothed, armed, invested with the authority of a particular god, ancestor, or institution, speech that does not program operations and produce results, speech barren and destitute. It is speech that is destined for all, speech that subjects whatever it says to the contestation of anyone from any culture or history or latitude, accepts any stranger as its judge.

Then what is distinctive about philosophy is not a certain vocabulary and grammar of dead metaphors and empirically unverifiable generalizations. One's own words become philosophy, and not the operative paradigms of a culture of which one is a practitioner, in the measure that the voices of those silenced by one's culture and its practices are heard in them.

I

Tenochtitlán was written in Mexico City in 1988

Photograph: Mummified child in the cemetery at Guanajuato.

Tenochtitlán

There were no cars parked in the streets, and no one walking. There were no shops, no sidewalk stalls of newspapers or soft drinks. I inquired several times from the armed police at corners to find the street. Rows of trees stretched over ten-foot-high stone walls with two or three electronically operated doors cut in them on each block. When I found the number, I pushed the buzzer and identified myself on the intercom. The lawyer himself opened the door for me. Our mutual acquaintance in the States he had known for years; they had first met, he said, on the beach, at Cancun. He invited me to pull my car inside his compound. "A hundred cars a day are stolen in this city," he said with a smile, "and yours is new and beautiful." He led me into his marble-floored home, introduced me to his wife, also a lawyer. We sat in the salon; a maid put margaritas and hors d'oeuvres on the onyx table before us. When he built this house, the lawyer recalled, Tlalpan was a village on the south of the city, blessed with its clean air at the base of the Ajusco volcano. Already at the beginning of the colonial period, the viceroys built subsidiary residences here. Now many movie actors and actresses live in Tlalpan, in palaces I did not see behind those walls. There is also a medical center reserved for senior government officials; it is decorated, the lawyer's wife said, with frescos by Siqueiros, Chavez Morado, and Nishizawa. The lawyer and his wife had both

decided to retire two years ago. Since then, they traveled, to the States, then to France, Spain, and Italy, after that to Japan, Singapore, and Hong Kong, most recently to Australia. They had visited our mutual acquaintance in Philadelphia, and he had come to visit them, stayed with them in Cancun and in Acapulco. The lawyer's wife asked me about Kathmandu; I also described Bali and Bangkok. We had another margarita and then another. We got up to go contemplate an African mask over the fireplace, a tenth-century Khmer Buddha in the hall, an Australian boomerang. We went at random from one continent to another, savoring the names of new places to go to.

In Honduras they are filling cargo ships with pineapples, coffee, and tobacco for us; at the port of Balikpapan in Kalimantan they are filling the oil tankers that will fuel the cargo ships; in the dunes of Morocco they are shoveling phosphates; on the beaches of Malaysia they are scooping up tin; in Zimbabwe they are digging in pits for the diamonds; in Zaire they are mining uranium. But we don't just stay home and wait for the doorbell to ring. We ourselves go there, to them. We go to Acapulco, to Jamaica, to La Paz, to Tangier, to Fiji, to Pattaya. We find ourselves welcome; jet package tours are one of the most important developments in the economies of former colonies in those continents since our last world war. In some of the smaller of these new nations the majority of the resident population consists of busboys, waitresses, gardeners, tour-bus drivers. Certainly we do not go to Acapulco to look into our investments there; one is on vacation. One does not go to poke around in the hamlets of a backwater of the civilized world; one stays in a Hyatt or an Intercontinental. We would not go there to find something for

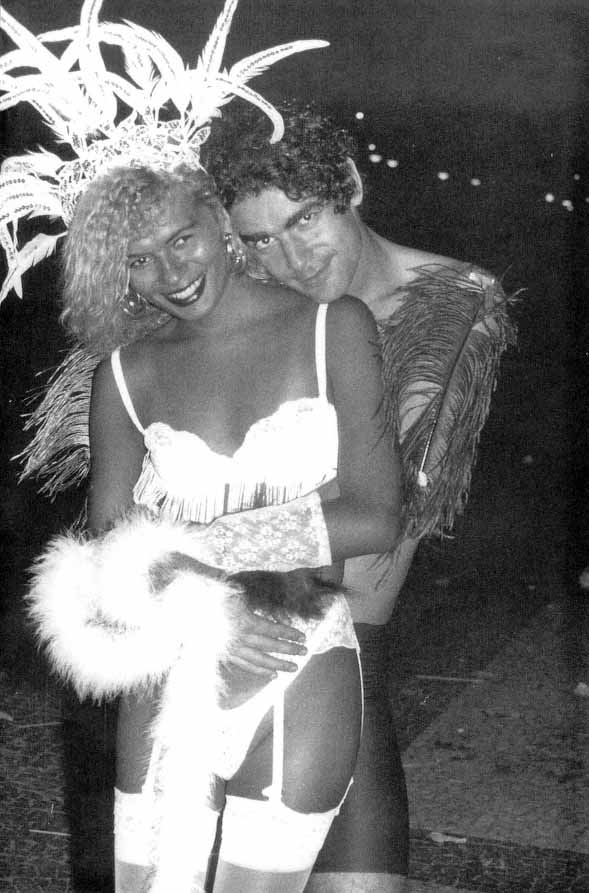

ourselves in the Aztec civilization swept into dust 450 years ago. One goes to the Anthropological Museum in downtown Mexico City. Or one did, until two years ago when the key pieces were dispersed in an unsolved robbery. In the past twenty years, enterprising bands of men have located most of the Maya sites in what is left of the Yucatán rain forests, dislodged their notable carvings with crow bars, and cut them with power saws into pieces of the size to decorate our living rooms. The pieces are to be seen in Austin, Nice, Kuwait. In Acapulco one bronzes one's skin, one swims, water-skis, goes parasailing, scuba diving, and shopping. One encounters the locals, the best-looking young creoles and mestizos and Indians, groomed, liveried, who bring cocktails and cocaine and themselves. In Pattaya the tourist season coincides with the dry season; for five month there is a resident population of fifty-five thousand prostitutes. But prostitute is too harsh and misleading a term for those upcountry adolescents who are the sole subsistence for whole families during the five-month drought. The airline hostesses are the geisha girls of these decades, and it is their affability, their availability, their graces, and their slang the country girls try to learn and imitate in their untrained and touching ways.

On the planes, we ship them back ourselves. They bought us, with all their bananas and uranium and diamonds. But we are not another commodity in the global economy. What after all can they do with us, but garland, feed, and massage us? The term prostitute decidedly belongs to an obsolete vocabulary. We have not sold them ourselves for money. For we have become values. That is, money.

The heat of the afternoon passed. The driver pulled out the lawyer's car; we drove through San

Angel where through wrought-iron spiked gates we caught glimpses into colonial gardens. We got out of the car at Coyoacán to visit the remaining outbuilding of Cortés's palace. On the site of the palace itself, a Dominican church had been built; the lawyer and his wife had been married there. Inside, benediction was concluding; we knelt as the priest swung the monstrance, a four-foot-wide gold sun, over us, Dominus vobiscum. We walked over to see a building said to be the palace of la Malinche, the Aztec girl who had traded her nation for Cortés's affections, and the house where Leon Trotsky was assassinated.

We returned to Tlalpan, we drove through the gates of a wall that extended across the whole block: this had been the home of a surgeon the lawyer had known since childhood, and who had lived here with his wife and one son. The building extended the full length of the block-long back wall; before it were gardens with sleeping swans and peafowl. The owners had sold the mansion with all its furnishings to a restauranteur and had moved to the Costa del Sol in Spain. Inside, the walls were decorated with huge portraits of racehorses. We ordered margaritas and hors d'oeuvres; the waiter brought three silver dishes with oily inch-long eel fry, white termites' eggs, and gusanos de maguey , finger-size segmented worms that are found in the maguey plants from whose white milk-sap the Aztecs derived, and today the campesinos derive, a fermented drink called pulque. The waiter showed me how to fold the wiry little eels into a tortilla with guacamole and piquant sauce. Then we had steak, cut, the waiter assured us, from bulls killed in the corrida the day before.

The lawyer refused me the honor of paying the bill. They would write our mutual acquaintance in

Philadelphia what a gift he had sent them in the pleasure of my company—how much I knew, how much I had seen. Back at the compound, the driver parked the lawyer's car and I unlocked mine. We embraced; how easily we had come to know and love one another! The lawyer went inside and returned to give me a blade of carved obsidian, which as a boy he had found in the rubble and weeds at Teotihuacán and which an archeologist had dated for him as belonging to the second half of the first century B.C. The Aztecs believed that the pyramid of the sun at Teotihuacán was built by the vanished Toltecs at the beginning of their cosmic era, that of the Fifth Sun, which Aztec astrologers and priests had predicted was to come to an end in the year Nahui ollin. It was in the year Nahui ollin that Hernando Cortés landed on the beach of Chalchuihcuecán, which he renamed Vera Cruz.

Between 1521 and 1536 Spanish conquistadors and missionaries put an end to all the great civilizations of America—Aztec, Mixtec, Zapotec, Pipil, and Inca. Of their cities, their social order, their science, their gods, wrote Bernal Díaz del Castillo in his True History of the Conquest of New Spain , "all . . . is overthrown and lost, nothing left standing."[1] Pope Alexander VI, who had granted to the Catholic monarchs of Spain and Portugal the lands of all the heathens of the world, issued bulls granting plenary indulgences in advance for all sins committed in the Conquest. The superiority of the new Christian dispensation did not lie in its horror of war and human sacrifice; the conquistadors conquered because their wars were more treacherous and their massacres more wanton. The superiority lay in that the Christian conquistadors brought love to the worshippers of Quetzalcoatl.

That is, money. Although Tenochtitlán, built in the crater lake of an enormous dead volcano, was an immense market, the Aztecs, the Egret People, did not know money. The wealth arrived as tributes and gifts, and was distributed by prestations and barter. Gold was used to plate the walls of temples; there were no gold coins in Tenochtitlán.

Tributes made, gifts given, impose claims on the receiver. A regime of gifts is a regime of debts. Marcel Mauss, in his work The Gift (1923),[2] showed that it is an economic system; indeed, it is the most exacting economic order. It is an economy of rigorous reciprocity; each gift proffered requires the return of the equivalent. In the economy of gifts man became man, that is, Nietzsche wrote, the evaluator.[3] The herd animal learned to reckon, to appraise, to calculate, to remember; he became rational. He learned his own worth. The self-domesticated animal, a productive organism with use value, became an exchange value.

Money introduces a factor of nonreciprocity. One receives something useful, and one renders in return artifacts without utilizable properties. There is immediate discharge of indebtedness. One arises as a person, free to choose and to give—a value unto oneself. "Working against the narrow and rigorous moral discriminations of Subsistence economies—where love cannot be developed as a value in itself though its semblances are enforced—money vitiates strict reciprocities and differentiates given roles and statuses so as to provide options impossible in situations where giving = receiving ," Kenelm Burridge writes. "Handling money, thinking about and 'being thought' and constrained by it, vitiates firm dyadic relationships and makes possible the perception of oneself as

a unitary being ranged against other unitary beings. The opportunity is presented to become and to be singular."[4]

When Hemando Cortés forced Moctezoma Xocoyotzin to take him to the summit of the Uitzilopochtli pyramid, the charnel-house stench of the blood-soaked priests of the war god filled him with revulsion. He prevailed upon Moctezoma to erect on the same summits as these demons images of Jesus Universal Redeemer and of the Virgin Mother. Yet the knights of Cortés certainly made no objection to the slaughter of captives and noncombatants, nor did their priests, who established the Inquisition in Mexico six years after the fall of Tenochtitlán. The Mesoamericanists today calculate the population of Mexico upon the arrival of Cortés variously between nine and twenty-five million; but they agree that it was reduced to one million during the first fifty years of the Conquest.

The Aztec civilization is singled out in revulsion for having made of human sacrifice a religious ritual. Bernal Díaz identifies Uitzilopochtli, "The Hummingbird of the Left," with Satan, since, without promise of any afterlife, the supreme religious act of his worshippers is the shedding of human blood. Only brave soldiers killed in battle or sacrificed were promised a return, to the earth as hummingbirds, whose plumage was woven into the shimmering raiment of the presiding Aztec officials. Bernal Díaz recognized here a religion of the most perverted form, utterly alien to any gospel, any kind of salvation.

Yet the conquistadors were not liberal Protestants assembling on Sundays for the purpose of listening to a moral exhortation; Catholic Christianity is a religion centered on sacrifice. The redemption brought to an earth damned since Adam's sin was wrought by deity

becoming human in order to be led to sacrifice. Each Sunday the Catholic community assembles before an altar in which that sacrifice is, not commemorated, but really reenacted. If each Christian is not enjoined actually to carry a cross to a gibbet in his turn, that is not because the sacrifice of the Son of Man freed mankind from any destination to be sacrificed; it is that he must not add his ransom to that of Jesus who gave his life for all men. But the Christian life can only consist in a real participation in the redemptive act of the Christ. To be a Christian is to make each moment, each act, each thought, each perception of one's existence a sacrifice. Not simply in partial and intermittent acts of mortification, which would compensate for acts of indulgence, but in a total putting to death of the flesh and of the world. "With Christ I am nailed to the cross. It is now no longer I that live, but Christ lives in me" (Gal 2:19).

The Aztec religion did not require quantitatively more human sacrifice than did the Christian. It was the purpose of sacrifice that differed. Jesus died for our redemption. In the Eden God created, nothing was wanting in the waters above and the waters below, in the skies and on the dry land; the only vice was man—more exactly, woman. Humankind corrupted itself, and against it several times the waters rose again over the dry land in a decreation, from which, for the sake of Noah, of Jonah, of ten just men in Ninevah, of Abraham, a remnant was spared. Paul recognized in Jesus a new Adam; the old mankind must now perish entirely. "For we know that our old self has been crucified with him, in order that the body of sin may be destroyed, that we may no longer be slaves to sin; for he who is dead is acquitted of sin" (Rom 6:6–7). The remnant saved by Jesus is

not cleansed but reborn, in the waters from which all skies, dry land, fishes and flying things, creeping and crawling things once came. The new life is destined, not for this now corrupted world, but for the new Eden, and for immortality. Through mortification of his whole nature, the Christian accedes to definitive deathlessness.

On the pyramids of Tenochtitlán, sacrifice had nothing to do with human salvation, nor with attainment of deathlessness through death. The Aztec religion was a religion not of eternity but of time. All the deities were units of time. Each day had its deity, each day was a deity, a deity was a day. If the Aztec astronomers climbed the summits of pyramids by night to chart the stars and record the comets and labored by day to calculate the periodicity of eclipses and meteors on the orbits of cosmic time, this astronomy and this mathematics were not of religious application; it was theology and of the most pressing cosmic urgency. For as each god has its day, each polyhedron of deities and each table has its time. Every fifty-two years all the orbits reach an equilibrium; the Aztecs could find nothing in all their nocturnal searching of the immense stretches of nothingness between the stars that would guarantee that this stasis could not continue indefinitely, and all motion, all life come to an end. It would then be necessary that motion be liberated, that it not be contained within the beings that move themselves. The Aztecs poured forth their blood in order to give to the most remote astral deities, suspended for a night in the voids, movement.

At the great ceremony of Cuahuitlehua, the children of the Egret People born within the past year were taken to the temple of Tlaloc, where the priests

drew blood from the earlobes of the infant girls and from the genitals of the infant boys. Adults regularly drew blood from their earlobes, tongues, thighs, upper arms, chests, or genitals. Each day in the palaces the nobles pierced their ears, their nipples, their penises and testicles with maguey thorns in order that blood flow to the heavens. The Aztec imperial order did not, like a Roman empire, extend its administration ever further over subject societies and economies; it existed to drain ever greater multitudes of blood-sacrifices toward the pyramids of the sun the Aztecs erected upon the earth, that monster whose maw swallows the setting sun, the remains of the dead, and sacrificial victims. A youth destined to have no children, the sacrificial victim, arrayed as a god Tezcatlipoca, "The Mirror's Smoke," ascended the pyramid to the heavens: he was man set forth as the absolute value, absolute as that which does not exchange what belongs to him for anything he or his kin could receive in return. Theologian Bartolomé de las Casas wrote: "The Nations that offered human sacrifice to their gods, misled idolaters that they were, showed the lofty idea that they had of the excellence of divinity, the value of their gods, and how noble, how exalted was their veneration of divinity. They consequently demonstrated that they possessed, better than other nations, natural reflection, uprightness of speech and judgment of reason; better than others they used their understanding. And in religiousness they surpassed all other nations, for the most religious nations of the world are those that offer in sacrifice their own children."[5]

The conquistadors and the monks brought love to the Mexica. The Aztecs, Bernal Díaz reports dismally, were sodomites, as were the Mayas of Cape Catoche,

the Cempoalans, the Xocotlans, the Tlascalans. Sodomist was their religion: In the first Indian prayer house he and his companions came upon on the Mexican coast, Bernal Díaz reports finding idols of baked clay, very ugly, which represented Indians sodomizing one another. Of the Indians of whom the conquistadors had any knowledge, the exception was Moctezoma II himself, despite his gastronomic taste for the flesh of young boys. It was this, rather than his elegant manners and his gullibility, that commanded the respect of the conquistadors. Cortés assigned a Spanish page to him to test him, and found him incorruptible. When, during the final battle, they turned on him with daggers, Moctezoma requested Catholic baptism. The priest, occupied in breaking through the walls of the palace in search of the treasure, did not come; Moctezoma died without the Catholic redemption. Today he is worshipped as a god in San Cristóbal and Cuaxtla.

The sodomy Bernal Díaz perceived is not contemporary homosexuality, nor that of Greek classicism and Renaissance humanism. Sodomy, determined in the juridic discourse, civic and canonical, of Christendom, is conceptualized not as a nature but as an act, a transgression of divine, human, and natural positive law. Not simply unnatural, according to the ideology of perversion and degeneration of the modern period, which explained it positively by a fault in nature, explained it thereby by nature—sodomy is antinatural. It issues not from an unconscious compulsion but from an intellect that conceives the law and a will that determines to defy it; it derives from libertinage and not from sensuality. Sodomy is the use of the erected male organ not to direct the germ for the propagation of the species nor to give pleasure to the

partner but to gore the partner and release the germ of the race in its excrement. It attacks the human species as such. Not only does it invert the natural finality of organs by which we came to exist; it is directed against the imperative to maintain the genus which every positive law, every universal, must presuppose. It is the last limit of outrage under the eyes of the monotheist god, God the Father, that unengendered principle of all generation and absolutized formula for the normative. It is the act that isolates, that singularizes absolutely. Positively, sodomy is the crime in which sovereignty is constituted and resides. It is the act, unmotivated and unjustifiable, that posits the singular one, the monster. This singular, singularizing act can only be incessantly repeated, rending the monotheist time of universal generation, conjuring up a cosmic theater without order or sanction in which trajectories of time rush to their dissipation.

When Cortés burnt his ships before advancing upon Tenochtitlán, when they were but four hundred slashing their way through the enraged Aztec citadel, what maintained the epic resolve in the conquistadors was their horror at falling into the hands of these sodomites and being sacrificed on the altars of their demons thirsty for the blood of the human species. "It must seem very strange to my readers," Bernal Díaz writes, "that I should have suffered from this unaccustomed terror. For I had taken part in many battles, from the time when I made the voyage of discovery with Francisco Hernandez de Cordoba till the defeat of our army on the causeway under Alvarado. But up to that time when I saw the cruel deaths inflicted on our comrades before our very eyes, I had never felt such fear as I did in these last battles." "I must say that when I saw my comrades dragged up each day to

the altar, and their chests struck open and their palpitating hearts drawn out, and when I saw the arms and legs of these sixty-two men cut off and eaten, I feared that one day or another they would do the same to me."[6] Certainly it was not the painfulness of the Aztec sacrifice as compared to the burning under slow fires that Cortés preferred (and which the Inquisition sanctioned, since this method of execution does not produce the shedding of blood, which would risk making the death of heretics an image of the shedding of the redemptive blood of Jesus) that so horrified conquistador Bernal Díaz; it was the monstrous and sodomist cause for which there was sacrifice.

Bernal Díaz knew that the Aztec priests daily let their own blood flow forth to their gods, and that the sacrificial victims, drawn from courts everywhere in the Aztec empire, and whom he perceived, through empirical induction from the idols he had seen at every stage of the advance toward Tenochtitlán rather than through knowledge of Aztec sexual legislation, to be sodomites, were treated as incarnations of the gods and climbed willingly the calvary of the Aztec pyramids. If Quauhtemotzin destined Cortés for sacrifice on the altar of Uitzilopochtli, The Hummingbird of the Left, it is because he perceived him as Quetzalcoatl. What then would be a sodomite who sacrificed himself?

Aztec sacrifice was not at all for our salvation, for the salvation of the Mexica, the people of Anahuac, "The One World," or of the human species. Its purpose was cosmic and not anthropocentric; with the volcanic obsidian dagger the human blood is released for the sake of the cosmic order or, more exactly, in order that the diurnal gods rise and fall, that the divine trajectories of time rush to their extinction. The

blood that makes our bodies move themselves is released from them in order that time and not the stasis of eternity be. The apparition of the human species and the reproduction of a human politico-economic order are not guaranteed by a cosmic order, but are sacrificed to move the cosmic trajectories to their expiration. This religion assigns to man the most exorbitant destiny ever conceived in any system of thought.

The destiny their religion assigned to the Egret People requires an existence that has broken with that of homo politicus, homo oeconomicus, an existence no longer a subject of, and a value in, reproduction and production. Such a human existence is no longer commanded by a nature that maintains itself—no longer commanded by universals without (incarnated in the individual in the form of the instinct to reproduce the species) nor by self-regenerating compulsions of one's own sensuous nature. The Aztec sacrificial offering is an existence that realizes absolute singularity.

In Christendom sacrifice is required by original sin. The concept of a sin of which all humans are guilty because all are Adam's children is not really the epistemological short circuit produced where the juridic concept of guilt was wired into the biological idea of heredity. Sin is not the ethical-juridic concept of guilt which is elaborated in the theory of voluntariness in Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics. Ethical culpability is imputed to the will and is coextensive with consciousness. One's sin exceeds the measure of consciousness, as all the anguish of Job argues, and the sinner must first pray to know his sin. The notion of sin, depicted as exile, retains what was essential in the archaic notion of stain: evil as a state.

The movement in the act that puts one in the state of sin is not the transgression as such, transgression of a positive law of the order in which one has been domesticated; in the sinful act there is a turning away, an existential conversion from God out of which all transgressions issue.

The concept of original sin identifies the origin of this deviation not in the conscious choice of the individual but in the individual as participant in the history of a people. Saint Augustine of Hippo saw that the tale told in Genesis does not isolate an individual faculty of choice but depicts a collusion of male and female nature in the tasting of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

Born of flesh, the individual turns back to flesh and to the state of sin that is in all flesh. Saint Paul, in the Epistle to the Romans, had spoken of the inner mystery of iniquity: "For I know that in me, that is, in my flesh, no good dwells, because to wish is within my power, but I do not find the strength to accomplish what is good. For I do not the good that I wish, but the evil that I do not wish, that I perform" (Rom 7:18–20). The flesh, in Paul, is not a concept related to the Aristotelian physics of the hylomorphic composition of human substance; it is the emblem of the opacity of a will that does not effect itself.

In Eden, Saint Augustine explains, the will in mind which views the goodness of creation directs the sensuous will; orgasm occurs when the will in sensuous nature sinks into itself and the will in mind collapses. The supreme pleasure of orgasm is supreme not simply in quantitative degree but in that it is most fully one's own; one's will actively participates in and wills this collapse of will. Orgasm is then not just the exemplary, or the most compulsive instance

of the will not effecting itself; it is the realization of sin as a state—original sin as originating sinfulness, a state where the will does not perform the good because it wills its own nullity. The existential exile involved in the originating sinfulness is a turning toward nullity; it is also, for each one, his or her primary way of participating in the history of a people. One's sinfulness is not a property, like racial color or specific morphology, that would be transmitted in the conjunction of sperm with ovum; it is an antiproperty, it is the willed defection of will in which one is conceived and conceives.

In the time of Noah, of Jonah, of Abraham, the Creator did not hesitate to engulf the material world in order to put to death carnal humankind. The Christ eternally engendered by the Creator became incarnate, entered into this flesh of nullity, in order to be sacrificed, and in order to put to death with his death carnal concupiscent humanity. In Jesus the Creator of the material world is himself put to death in order that his creation no longer conceive and reproduce in sin, in order that through the death of carnal nature humankind accede to deathlessness.

The Christian lives in the image and likeness of God, in the imitation of God; he and she procreate as God creates, as the Virgin Mary conceived, without the orgasmic delirium. The Christian reproduces human life in an act of making of his or her carnal nature a sacrificial offering.

Augustine's theology does not devalue man's carnal nature but values it absolutely in the divine economy of redemption. In the economy of sin, giving himself the supreme pleasure of orgasm, man ever augments his debt, which cannot be paid out of the nothingness of will concupiscence engenders. In the sublime economy

of redemption, the substance whose use value is null, the carnal nature willing its own nullity of will, becomes the measure of the exchange value of all goods of use value. The value of concupiscence is no longer measured by the new, but equally concupiscent life it produces. The value of our carnal substance is measured by the infinite value of the flesh of God sacrificed to redeem it and by the infinite series of earthly goods to be sacrificed for its unending mortification. It is the money of the city of God.

There is an inner economy in the man who participates in political economy, in the City of Man and in the City of God. It is by reason of his organism that man is homo oeconomicus. It is also by reason of the economy of the polis that the infant becomes an organism.

An infant is tubes disconnected, corpuscle full of yolk put out of the fluid reservoir of the womb, gasping, gulping free air, pumping, circulating fluids. The disconnected tubes are open to multiple couplings, multiple usages. A mouth is a coupling that draws in fluid, but can also slobber or vomit it out forcibly; that babbles or cries, can pout, smile, spit, and kiss. From the first the mouth that draws in sustenance also produces an excess, foam, slaver, extends a surface of warm pleasure, an erotogenic surface in contact with the surface of the maternal breast. The coupling is not only consuming, of sustenance, but productive, of pleasure, spread, shared. The anus is an orifice that ejects the segments of flow, but also holds them in, ejects vapors, noise, can pout, be coaxed, refuses, defiles, and defies. And spreads its excesses, producing a warm and viscous surface and surface effects of pleasure. The excrement is waste

and gratuity; it is the archetypal gift, which is a transfer without recompense, not of one's possessions, one's things, but of oneself.

In time, the hand couples onto the penis, finds the surfaces of contact productive of viscous warmth, spreading a surface of pleasure. The child discovers the pleasures of wasting his seed; he smears around this liquid currency, he produces a surface of waste again, and surface effects of pleasure. He adheres to this viscous pleasure, wills this waste, this nullity; this will actively participates in and wills this collapse of domestic will. He would like to seduce the mother into this potlatch economy.

These developments are being watched. The other intervenes, the father. The father claims proprietary rights over the mother, interdicts masturbation. The paternal word is not indicative, informative, but imperative; it is prohibition, it is law. The son is sentenced to castrate himself, that is, excise his penis as an organ for the production of pleasure, take it definitively out of anyone's reach.

The father had renounced his own presence as an erotogenic surface laid out before the infantile contact, in order to figure before the child with the force of his word, as law. The word of the father becomes incarnate in the son in order to castrate the penis through which the infantile substance is squandered so as to put this production of nullity, this collapse of domestic will, to death. He puts it to death with his own death, with the excoriation of his own flesh craving for erotogenic contact with his son. The father became incarnate in the son in order to be sacrificed and in order to put infancy to death with his death.

The child laughs at the paternal threat, empirically most frequently formulated in the name of the

father by the mother, even as she fondles him. He will take the paternal word seriously the day he discovers the castration of the mother. In horror he learns that the mother has already been mutilated. The law is sanguinary.

At the same time he comes to realize the chance he is. He comes to understand that he has been pulled forth from that gaping wound between her thighs; he comes to understand that he is the organ of which she has been castrated. He comes to understand why all this time she has been holding him close to herself, fondling him, drooling over him. He recognizes reflected in her eyes something he has not touched nor felt touched by her: the phallus, absent organ severed from her, separated from him, not even an image he sees in her eyes, only a floating mirage before them or a sign sought out by them. He formulates the project of making himself be that phallus of which his mother has been mutilated, in order to hold on himself her narcissist love. He sets out to identify himself wholly with this phallic phantasm. He understands that her solicitude for his needs reduces him to servility and parasitism; he understands that she satisfies his needs in order to frustrate the demand for gratuitous devotion, love, his infancy put on her. He will exchange all his infantile needs for the phallic contours, phenomenal form of void, he parades before her as an insatiable sign, appeal and demand. It is this total investment of himself in the phallus that makes it possible for him to effect the castration of a part, his penis as immediate pleasure-object, the paternal word demanded, as well as the polymorphously perverse erotogenic surface production about it. The phallus is the phantasmal substance, of no use value for the

production of erotogenic pleasure, for which all carnal surfaces utilizable for the production of pleasure are exchanged—the carnal form of money.

In internalizing the paternal law as the law of his inner libidinal economy, in engendering a superego, the son puts himself in the place of the father. When he now comes to the mother and her successors with his penis, it will no longer be in surface contacts producing immediate gratification. They now meet in a monetary economy where nonreciprocity, love, is at stake. Inhabited by the mystical body of the father, the son does not now exchange his phallic value for penile gratification; instead, his real penis is now put in the place of the phallus, becomes a phallic metaphor, an imperative sign demanding love, becomes that for which all goods and services are exchanged: money. Phallic value is the obverse of erotogenic use value; it is measured by the quantity of goods of use value which are exchanged for it.

The sodomite in the eyes of Bernal Díaz contemplating the high priests of the Mayas, the Compoalans, the Xocotlans, the Tlascalans, and the Aztecs is then one that erects his real penis in the place of the ideal phallus and uses it to disembowel paternity and execrate infancy. Human sacrifice, common to the principal cultures of Mesoamerica—Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, Huastec, Totanac, Toltec, and Aztec—had accelerated in inverse-Malthus algebraic proportion. It was necessary that the Aztec world maintain a continual state of war, waged not for political domination, territorial conquest, or plunder but for the sake of constituting brave and noble men as sacrificial stock. The conquistadors and their priests heard that when in 1487 Auitzotzin dedicated the pyramid of Uitzilo-

pochtli in Tenochtitlán, twenty thousand humans were sacrificed. The Aztec order, dazzling and frail as its lord Uitzilopochtli, The Hummingbird of the Left, had succeeded the Toltecs whose pacific deity Quetzalcoatl, The Plumed Serpent, had gone beyond the seas to the east; Moctezoma Xocoyotzin held himself in readiness to sacrifice resolutely the entire Aztec world upon his return. In the perception of Quetzalcoatl Hernando Cortés, it had become an infernal sodomist machine turning for the damnation and annihilation of mankind. Hernando Cortés hurled himself against it, worshipping the Son of Man, driven by his sense of the value of man, and of gold.

The sodomist perversion, as perhaps every perversion, is a perversion of the rationale of economy; the exchanges can no longer continue by way of compensations, The sodomist phantasm put in the place of the possible utility of the human organism does not have the phenomenal form of value, exchange value; it is an unevaluatable value. The perversity lies in the inexchangability of the sodomist position. Recognizing a sodomite in the Aztec, Bernal Díaz recognizes a sovereign singularity, a cosmos severed from every genus, exterminating angel, an angel in St. Thomas Aquinas's eidetic definition, alone in his species, unreproducing and without kin, an individual that exhausts the species, that comes to be in laying waste the species. But what he, craving salvation, redemption, and gold, could not understand is that the supreme act on the pyramid of Uitzilopochtli was the sacrifice of this sovereignty in order that the gods exist, that the trajectories of time run their course. We should not say: that the cosmos turn, for there was precisely not, without blood, an order that would maintain the terrible dispersion of the heavenly bodies in the immensity of the nothingness.

Sacrifice of the monstrous sovereignty in order that the universal dispersion be a cosmos. In order that the movements of time depart.

The monstrous splendor of the absolute value does not have the phenomenal form of value, exchange value. The proprietor of the absolute value does not exchange what belongs to him for anything he could receive in return; he gives in order to not receive. One has, to be sure, received one's existence. In giving one's existence to the universe, has one then perceived anything more than exchange value in that existence? The reality of the more could only consist in giving more than one is, as servility is constituted in receiving more than one can give in return. The giving, with one's existence, of more than one is was the exorbitance to which the Aztecs destined themselves.

It was at Cholula, on the pyramid of Quetzalcoatl, the greatest structure ever built on this planet, 1,600 feet square, rising over forty-three acres, greater than the great pyramid of Cheops in Egypt, that the sacrifice was fixed in its canonical form. The sacrifice was the most beautiful male of his year, face painted gold, wearing jade bird's mask of the wind god, on his throat a jewel in the shape of a butterfly, wearing golden socks and sandals, clad with a mantle of glittering green quetzal plumes, a diadem on his head. For forty days he went through the city dancing and singing; the crowds adored him with flowers and exquisite food. He was given to drink crushed coca mixed with human blood and peyotl. At length the appointed day had come. He ascended the great pyramid, lay spread-eagled on the sacrificial stone for the black-faced priests to open his breast with obsidian daggers to pull out his heart, and for the nobles to

partake of his flesh and blood. Not a nourishment, human flesh with human flesh: Eucharist of Quetzalcoatl, the departing one.

Moctezoma Xocoyotzin had been completely informed of every detail of Cortés's ships—his horses, his supplies, his arms, his acts. He had sent his priests to Cortés with a turquoise mask splayed with quetzal plumes, that of the priest of Quetzalcoatl. He had repeatedly sent emissaries with tribute more and more in excess of what Cortés told them he had come for. Now Cortés was in the city, with his four hundred men, his fourteen pieces of firearms, surrounded by two hundred thousand armed Aztecs. One day Cortés asks for an audience with Moctezoma, seizes him, puts him in house arrest in his own palace. Moctezoma takes every precaution to make sure that his generals do nothing whatever, he accedes to all Cortés's wishes, including the desecration of the most sacred temples. Each day he conceives more and more lavish gifts of gold objects, and orders them to be brought to Cortés. Moctezoma, tall, lean, elegant, dressed in white embroidered robes which are worn but once and destroyed, adorned with jewels and glittering plumes, the sole Aztec proved not to be a sodomite, is, Cortés perceives, mesmerized with love for him. Cortés trims his beard, practices the most ceremonious Castillian manners, fondles his sparkling gifts like a courtesan, and speaks each time of the great love he has for Moctezoma. He keeps Moctezoma from his harem and distributes to his subalterns the princesses Moctezoma offers him. He must be bought with gold, with daily gifts of ever greater piles of gold jewelry, with armies, with an empire, with a whole civilization. When Moctezoma was dead, Bernal Díaz reports that not one of the

troops of Cortés received a single gold piece from the plunder; Cortés had appropriated it to the last dram. His pay for the love of Moctezoma.

What is ordinarily called prostitution is the merchandizing of one's organism, that first and fundamental object of use value. The term "prostitute" is used as an epithet hurled to insult and devaluate someone. Yet does not one become a value through prostitution? There are distinct forms of value, and distinct forms of prostitution. There are those who rent out their bodies for wages, that is, for the sustenance costs involved in maintaining and reproducing themselves. One does not need galleons of gold; renting a prostitute's body for the night is within the means of any sailor or student with a summer job. For one does not pay her in terms of the incalculable value of the voluptuous emotion received but in terms of what any working woman needs to keep herself in business, as, in capitalism, one pays a factory worker not the equivalent of the surplus value his labor contributes to the raw materials but the cost of the sustenance he requires to reproduce himself as manpower.

It is marketing by procurers that makes it possible for prostitutes to sometimes command enormous prices. Their use value is determined by the labor hours released for productive and commercial activity in their possessor—one hour of personality N is worth to the entrepreneur in advertising effectiveness eight hundred billboards erected along freeways. The voluptuous emotion provoked in consumers by the body of Farrah Fawcett or Mark Spitz is worth so much in terms of shampoo or swim trunks sold. Paying cash makes preserving human dignity possible. It is the basis of the distinction between those firm tits

and bulging cock, rented out, and the person as such, transcendent focus of choice—that is, proprietor now of the means for appropriation of any commodities whatever.

Sade's Nouvelle Justine stages a third possibility: that of being driven to sell oneself, not out of penury, but out of extravagant wealth. One then forces oneself on the market, not as a usable object of exchange value, but as that against which the use value of all organisms is measured, that is, as money.

Such a soul, where venality is pure and nowise motivated by the material needs of human nature, we can contemplate writ large in the El Dorado imagined by Sade.[7] The most generalized form of exchange value, the monetary form, requires that all objects of use value can be exchanged for one item absolutely indeterminate in use value. In the monetary economy being extended across the planet outside of Sade's prison cell, each good of real use value is evaluated in terms of its equivalent in gold, the least useful of available substances, less useful than dirt or rocks. Gold is the most useless metal both by reason of its properties and because of its scarcity. Were it abundant one could plaster one's walls with it, for though it is too soft to use in implements, it is as good a nonconductor of heat, cold, and sound as lime. Sade dreams of an economy in which the entrepreneurs would be paid by the consumers not in cash but in women. The entrepreneurs would in turn pay the labor force in women. The stock of women destined as currency in the economy would have to be maintained by the labor of other women, who for their labor would be paid in men.

In Sade's time English merchants on the banks of the Monomotapa and the shores of the Gulf of

Guinea expressed the value of all commodities in terms of human beings. Thus four ounces of gold, thirty piasters of silver, three-quarters of a pound of coral, or seven pieces of Scottish cloth were, according to Father Labat, worth one slave[8] But a slave is an organism, that is, a living substance organized by a political economy; it is the first and fundamental object of use value. In order to function, in the El Dorado imagined by Sade, as money, the women and the men for which all usage objects are exchanged must themselves be without use value. Simply maintaining possession of them does not liberate the possessor of a quantum of hours to be devoted to productive and commercial activity. They are not to be used for reproductive copulation, which yields the possessor potentially enterprising offspring. The time they are in the hands of their possessor is occupied in the production of an unprofitable and sterile voluptuous emotion. All one can do with the inert form of currency, one's gold, is fondle it. All one can do with live currency is fondle, caress, massage, blow, spread it. These objects are without use value by reason of their scarcity as by reason of their properties. They do not have rare physiognomy or charismatic personality that could be marketed. They have the shape of retired stockbrokers, the charisma of dentists' or professors' wives. For El Dorado is, we now know, in south Florida.

A living organism becomes currency through venality—when, in a society where all things of use value are exchanged for gold, the gold in turn is appropriated by one who gives in exchange only the gratuity of voluptuous emotion. The voluptuous emotion, evanescent and sterile discharge, acquires preeminent value in a political economy by reason of its

capacity to render goods of use value useless. The measure of its value is calibrated by the number of those it can deprive of useful goods. Juliette, through years of indefatigable asceticism, has made herself available for any conceivable debauchery. Her utter contempt for all norms and rights has made her immensely rich; now she is ready to sell herself. She has nowise made herself an object of exchange value; she knows so in knowing that she has never parted with a sou for the alleviation of any case of human misery. It is a bliss not to be underestimated; according to St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, the blessed in heaven spend their eternity watching the torments of the damned, ut beatitude illis magis complaceat.

There arrived in Seville, on December 9, 1519, the first ship from Anahuac laden with Cortés's gold—bells and jewels, earrings and nose ornaments of exquisite workmanship, a gold wheel seventy-nine inches in diameter, an Aztec calendar swarming with designs hammered out in repoussé. In August of 1520 Albrecht Dürer came to see them and wrote in his diary: "I have never seen anything heretofore that has so rejoiced my heart. I have seen the things which were brought from the new golden land . . . . a sun entirely of gold a whole fathom broad, likewise a moon entirely of silver, equally large . . . also two chambers full of all sorts of weapons, armor and other wondrous arms, all of which is fairer to see than marvels . . . these things are so precious that they are valued at 100,000 gulden, I saw among them amazing artistic objects that I have been astonished at the subtle ingenia of these people in these distant lands." In the course of time the mints of New Spain coined some two billion dollars worth of currency, and two

billion more were exported in ingots. Two-thirds of the entire silver supply of the world was eventually shipped from the port of Vera Cruz. It was the ruin of Spain. The intricate irrigation system of the Moors, which had made of the Iberian peninsula gardens that fed an empire in Africa, crumbled into ruins; famine ravaged the countryside; and goats sheared the soil even of weeds so that the topsoil was burnt and eroded to leave the rocky desert the peninsula is today. Spanish manufacture and crafts were bankrupted, the guilds were disbanded, merchants were ruined. The cities became hostages of their fifth column of subproletariat, the countryside of bandits. Finally, the Spanish throne fell to Napoleonic armies, and the Creoles in New Spain emancipated Central and South America from Spain within twenty years. The race of Spaniards whose organisms figured in the economy as objects of use value entirely exchanged for Moctezoma's gold, which is exchanged for the figure of Hernando Cortés. Man ofinestimable value.

What did the knight of faith look like? "Hernán Cortés," wrote Gómara, "was of a good stature, broad-shouldered and deep-chested; his color, pale; his beard, fair, his hair, long. . . . As a youth he was mischievous; as a man, serene; so he was always a leader in war as well as in peace. . . . He was much given to consorting with women, and always gave himself to them. The same was true with his gaming, and he played at dice marvelous well and merrily. He loved eating, but was temperate in drink, although he did not stint himself. He was a very stubborn man, as a result of which he engaged in more lawsuits than was proper to his station. . . . In his dress he was elegant rather than sumptuous, and was exceedingly neat. He took delight in a large household and family, in silver

service and dignity. He bore himself nobly, with such gravity and prudence that he never gave offense or seemed unapproachable. . . . He was devout and given to praying; he knew many prayers and Psalms by heart."[9]

What does the knight of faith look like? Kierkegaard wanted to know. "People commonly travel around the world to see rivers and mountains, new stars, birds of rare plumage, queerly deformed fishes, ridiculous breeds of men—they abandon themselves to the bestial stupor which gapes at existence, and they think they have seen something. This does not interest me. But if I knew where there was such a knight of faith, I would make a pilgrimage to him on foot, for this prodigy interests me absolutely. I would not let go of him for an instant, every moment I would watch to see how he managed to make the movements, I would regard myself as secured for life, and would divide my time between looking at him and practicing the exercises myself, and thus would spend all my time admiring him. . . . Here he is. Acquaintance made, I am introduced to him. The moment I set eyes on him I instantly push him from me, I myself leap backwards, I clasp my hands and say half aloud, 'Good Lord, is this the man? Is it really he? Why, he looks like a tax-collector!'"[10] But not tax collecting, just on a tax write-off: those pale men and women, those values, shipped off to Acapulco, to Cancun, to Barbados, to Tangier, to Sanur, in exchange for all the gold, the diamonds, the uranium, and the bananas.

A Doctor in Havana

A Doctor in Havana was written in Havana in 1991.

Speech can be impulsive, ideolectic, capricious, inconsequential. What we call speech that is serious claims to speak the truth. The truth concerns the community. Statements can be true only in the discourse of an established community which determines what could count as observations, what standards of accuracy in determining observations are possible, how the words of common language are restricted and defined for use in different scientific disciplines, practical or technological enterprises, ritual practices, and entertainment with others.

Every community excludes certain statements as incompatible with the body of statements established as true. Every community excludes certain kinds of statements as not being able to be true. Every community excludes certain individuals, whose basic anti-social act consists in not making sense, identifying them as fanatics, as subversives, mystics, savages, infantile, insane. One does not answer what they say seriously, one meets what they say with silence, one employs force—the force of pedagogy, psychiatry, and the police—to make them speak in the ways of truth.

Torture is not simply the persistence of animal savagery in institutionalized forms of society. Would the solitary monster be produced not by an atavist regression to the instincts of beasts of prey but by a condensation in him or her of violent methods

elaborated in institutions? It seems clear that confirmed rapists act not out of the raw sex drive stripped of social control but out of the contraction in them of the institutional imagos and practices of the millennial patriarchal society. The one who gouges out the eyes of his victim has not regressed to the presocialized instincts of apes but has ascended to the ranks of the Ottoman Janissaries and the Roman Inquisition. The one who gouges out his own eyes, who devises dungeons and gibbets for himself, has made occult pacts with the dark powers of the social order.

The torturer works to tear away at the victim's body and prove to him that he is a terrorist or psychotic and that what he believed in is delusions. The victim himself must supply the proof, by his confession. He is not being asked to declare to be true what he knows to be false. The torturer demands of the antisocial one that he confess that he is incapable of the truth, that his bestial body is incapable of lucidity and discernment, that it is nothing but corruption and filth.

Torturers are armed with the implements supplied by ancient practice and modern psychotechnology. They are agents working in the Intelligence Division. The instruments and techniques of torture do have the power to render a body impotent and brutish, tearing away at its integrity, proving it is spineless and gutless. Modern pharmacology each week provides new methods to neutralize the organic chemistry that crystallizes visions and that exudes convictions.

The confession uttered will be integrated into the common discourse that circulates in the community, and which each one joins whenever he speaks

seriously. The cries and bestial moans out of which it came will be lost in the night and the fog.

To speak seriously is not simply to establish and communicate what is true. To speak is to respond to someone who has presented himself or herself. One catches up the tone of his address, her question, his voice resounds in one's own, one answers in the words and forms of speech which are hers. To respond is to present oneself, with one's past, one's resources, and the lines one has cast ahead of one—offering them to the one that faces, whose voice is an appeal and a contestation.

As one speaks to the one present, one responds to him with the voice of the child one was, of one's parents, one's teachers, responds to the words of persons who have passed on, who have passed away. And one offers a response not just to close the question in the now; one's response already invokes her assent or her contestation. When, on the Himalayan path, someone asks one the way, one's response addresses the hour ahead of him, or the days, or the lifetime, and undertakes already to answer for it. One always speaks to the departed, and for those who will be there after one departs. One's words answer for one's death and for the time after one's death.

Speech can be carefree, nonchalant, and frivolous, its patterns forming only to decorate the now of our encounter. But when it is serious, it speaks for the silent and silenced.

A relay for the circulation of the established discourse, the I arises in the effort to speak on one's own. To do so is to silence the circulation of the established truths in oneself. One's silence is tortured by the spasms and

pain of silenced bodies with which those truths were established. One's silence tortures them: AIDS victims identified by established means of research as homosexuals and drug addicts cast out into the streets, Africans not heard by jetliners roaring overhead without dropping tons of the surplus grains heaped up in American granaries, Quechua peasants delivered over to military operations programmed in Pentagon computers, forty thousand children dying each day in the fetid slums of Third World cities, an Auschwitz every three months.

One has to speak for the silenced. But does not one's own speech silence their outcries? One gathers up the words of defiance and faith uttered by those shot before mass graves, one gathers up the words they left with their comrades, their children. One publishes the diaries of Ché. The established discourse, having consolidated its forces to determine things and situations by their death, easily proves they are the economic plans of the unemployable, the political hallucinations of the unsocializable, the utopian programs of fanatics, Maoists in a Peru which is 60 percent urbanized. The documentation of their agonies neutralizes itself.

Responding to those who approach and speak, one captures their voices in one's own, and one's voice animates only the words and forms of speech and the truth of those who have passed away. In the formulations of one's significant speech the cries of the tortured are muffled. Screams in the night are translated into images that circulate in electronic transmitters. They merge into the din of machines and the collisions of nature.

The words and the images relayed die away into a silence heavy with muffled sobs and screams. One's

own words choke one's voice; they postpone the day when one would lay down with the tortured, to wash their wounds, weep with them. Even then, one must speak on one's own. The words that are one's own are not certifications but responses that are questions and pledges, answering now for one's silence and one's death and for the time after one's death.

"Luis is a plastic surgeon and burn specialist. Luis was visited by a government official who told him that two young women, one Brazilian and the other Uruguayan, would soon be brought to his office for evaluation and treatment. He was urged to provide them with extra-special attention, for their problems were of an unusual nature and required utmost sensitivity.

"It turned out that the two were participants in the urban guerrilla movement in Brazil, whose then military regime had gained a worldwide reputation for brutal and 'inventive' torture of political prisoners. The two women, whose names Luis never learned, visited him in his office, separately, that day.

"It was not physical pain that Luis's two new patients displayed, for their wounds or afflictions were not very recent. As soon as they walked into his office, Luis understood the magnitude of barbarism that had been visited upon these two otherwise normal and attractive women.

"They had been captured in Brazil and taken to the infamous DOPS, an acronym for the regime's special counterinsurgency police. There, they expected, they would be tortured and interrogated for days on end, as so many of their comrades had been—many dying in the process, others surviving as half-vegetables, and a handful freed as a result of

successful guerrilla actions. The women knew that 'special treatment' was reserved for members of their sex—the sexual depravity of Brazil's torturers, especially one named Fleury (who led the Death Squad in his spare time), had become well known. So terrible and sophisticated had torture become, as documented by Amnesty International, the Bertrand Russell Tribunal, and other human rights agencies, that the opposition movement had instructed its members to resist or try to resist for at least 48 hours—to give the organizational structures and comrades with whom the captured members had contact time to change addresses, codes, meeting places, etc. It was assumed that the prisoner would be made to talk. It was only the rarest of cases that could totally resist, maintaining absolute silence in the face of such devastating methods.

"Their expectations and fears turned out to be wrong, strangely enough. After several hours of being made to wait in a locked, bare room, they were taken, blindfolded, for a ride to what turned out to be a modern, well-appointed hospital or private clinic some distance from São Paulo. They were locked into rooms without windows, given hospital gowns, and told they would be given the 'best of treatment' and would 'get better soon.' Doctors and nurses, courteous but closed-mouthed when asked what was going to happen, took the women's vital signs and medical histories—the normal routine before surgery. Fresh flowers were brought into the rooms daily. A maddening sort of terror began to set in amidst all this antiseptic civility and preparations for treatment for a malady the women knew they did not have.

"As it turned out, the women themselves were the 'malady.' In their very flesh they would have to pay

for having dared to resist. The 'treatment' was different in the two cases, although identical in purpose. One of the women had her mouth taken away from her. The other lost half her nose. And they were released after several days with the gentle suggestion that they be sure to visit their comrades to show off their 'cures.' They had been turned into walking advertisements of terror, agents of demoralization and intimidation.

"It seems that, in the case of the woman whose mouth had been shut, the most sophisticated techniques of plastic surgery had been employed. Great care had been taken by her medical torturers to obliterate her lips forever, using cuts and stitches and folds that would frustrate even the best reconstructive techniques. . . . A small hole had been left in the face to allow the woman to take liquids through a straw and survive.

"During her initial interview with Luis, she had written on a piece of paper that 'they also did something to my teeth.' But when Luis and the medical team reopened the hole where her mouth had been, the sight was far more sickening than they had expected: All the teeth had been removed and two dog fangs—incisors—had been inserted in their place.

"'We did the best we could and gave her a hole resembling a mouth,' Luis said a few weeks later, 'and dentists will give her a set of teeth. But "ugly" is too kind a word to describe the way her mouth still looks.' Luis's face was tight, the color of a tightly clenched fist. Suddenly, he softened: 'But you know, that woman is extraordinarily beautiful. Do you know what she said after coming out of the anesthesia, her first words since undergoing her loss of speech? 'I will return. No one will ever silence me.'

"The other woman had had half her nose removed, skin, cartilage, and all. A draining, raw, and frightening wound was her 'treatment,' the sign she was to carry around with her to warn people that rebellion was a 'disease' and torture the 'cure.' Luis spoke little about her case, other than to say that a combination of skin grafts and silicone implants would restore a modicum of normalcy to her appearance."[1]

Tawantinsuyu

Tawantinsuyu was written in Qosqo, Peru in 1990.

The planet will be studded with computers capable of storing the contents of the world's libraries, which you can tap into from your home keyboard, locating anything ever formulated in signs with a few taps of your search key. On your screen you can delete and combine all calculations, all discourses. Extinct henceforth the tête-à-tête with the traveler, the explorer, the guru. The pagan learning and language of the Mayas burnt in 1526 by the first bishop of Mexico, Don Juan de Zumarraga, decoded after five centuries on a computer; the human species traced back to one aboriginal pair, not by faith in biblical revelation, but by genetic decoding on the supercomputer. All data on the nuclear winter revealed, not by seers and prophets, but by digital computation at the Max Planck Institute and Cornell University. Our brains, our sense organs, our feelings are now massively invested with information bits. Before going to make contact, with the Aztec ruins or with the migratory whales, we tap the search key on our computers and file in our brains the content of all the relevant library shelves on the topic. A few years ago it still seemed strange to us to notice all those tourists, not viewing the cathedrals and the waterfalls by the eye, but peering in their cameras viewing rather the preview of the snapshot of the urban monuments and the landscapes. We still thought viewing things directly could tell you something. What could any of us

learn from looking at Maya inscriptions? From looking at an occasional whale on high seas? The viewing is only an emotional indulgence. All we learn about these things we learn from our computer screen. The Antarctic continent buried under glacier millions of years old, but 3 percent of whose rocky edges is exposed during the six-month-long summer day, is projected by radar, sonar, infrared and microwave scanning onto computer screens in laboratories on other continents. Satellites continually photograph every centimeter of the visible surface of the planet, but the photographs are far too numerous for whole buildings full of geologists or intelligence agents to shuffle through; supercomputers will select and format the electronic pulses of which they are made.

But is it about things that we can learn anything? What we call perception is not the raw given, it is informed, formed by signs. Signs are significant only in contexts. The texts refer to other texts. The history of Egypt is the history of Egyptology. Physics is a discourse whose terms and rules for formulation are derived out of earlier discourses called physics or natural philosophy. The statement "Water boils at one hundred degrees centigrade" is not a law of nature, neither decreed nor obeyed; it is a definition. Matter and energy are not things you can encounter by looking; they are formulas in a tableau of calculations and illustrated by graphs on the coordinates of electronic screens. Images are not the faces with which the things confront us; things are made perceivable by contexts called culture, the transitory contexts of popular culture or canonized contexts called high culture, both materialized as digital programming and disseminated industrially. The image we see on our television screens, on the walls of our homes, or on

billboards is not a copy of an original; images are from the first matrices of reproduction. The role of the state is to produce media events which generate national confidence and pride and the national consumption of images of national products. There is no difference between a political act and its image; the political campaign was a series of photo opportunities, as are the subsequent meetings with heads of state. The things we imagine, seek out, encounter, accumulate are products generated in indefinite series by programs. Nature is the set of images we have been supplied in television specials, rain-forest and coral-sea, hummingbird's-eye and creeping-amoeba images whose colors are those of cathode-ray tubes, images cropped and spliced by graphics designers and made significant by a narrative in the vocabulary and logic and rhetoric of the current scientific and technological paradigms. Images are produced by information bits fed into programs; as they flicker across our receptor cells, our minds process signs, our cerebral circuitry formats, edits, files, networks.

It is now inconceivable to us that there could be a silent civilization, a civilization divested of all signs,

What there is left to contemplate is the Inca walls. What there is of Qosqo, "Navel of the Earth," is the wall of the residence of the Inca Roca on Calle Hatunrumiyoc, upon which the palace of the Marquis of Buenavista was cemented. What else can you do to find the world of the Incas? There are no inscriptions; they had no writing; their astronomy, cosmology, theology, epics, and chronicles were in the heads of the nobility who were all massacred or Christianized four hundred and fifty years ago. Archaeologists search in vain for statues, idols; they were all of gold and were

the first things to be smelted down by the conquistadors—all but the Punchao, the sacred sun disc of gold and precious stones, which was rescued by the last furious Inca assault on the conquistadors and spirited away to their retreat in the Andes and never located since. The first Inca Pizarro encountered, and captured by treachery, Atahualpa, was told he had the choice of being burnt alive as a pagan or strangled as a Christian. He accepted baptism for the sake of his wife and children, whom Pizarro promised to spare if they were baptized. After the Great Rebellion of 1536 and the final conquest of Qosqo by Pizarro, Manco Inca built a new capital in the inaccessible fastness of Vilcapampa. Four Incas reigned there until, in 1572, the Inca Tupac Amaru was lured out for battle, and hunted down in the Amazon jungle. He was given written assurances by the King of Spain that if he surrendered he would be treated as a prisoner of war. Tupac Amaru surrendered to save the lives of his people, and was dragged in triumph to Qosqo, where, in the cathedral square under the eyes of the Viceroy Francisco de Toledo and the bishop and the priests of the Inquisition, his wife was mangled in front of him and his head then struck off and stuck in a pole set up before the cathedral rising on the foundations of the palace of Inca Viracocha. In the year that followed the Inca nobles who had not been baptized and given in marriage to conquistadors were slaughtered. Vilcapampa, never found by the conquistadors but evacuated by its inhabitants, has to this day not been uncovered from its jungle grave. Toledo launched a vast program to round up the people from their settlements in the high Andes and relocate them in the strategic hamlets, the reducciones he ordered built in the lowlands and about the mines. "It is something

very convenient and necessary for the increase of the Indians, so that they could be better instructed in the articles of our Holy Catholic Faith and would not wander scattered and missing in the wilds, living bestially and worshipping their idols."

There remain the walls, foundation walls upon which the conquistadors built their palaces in Qosqo, the deserted terrace walls, aqueducts, and canals of Inca agriculture in the high Andes.

In 1911 the North American adventurer and later Senator Hiram Bingham announced that he had identified the citadel of Machu Picchu[*] with Vilcapampa, the capital of the last four Incas, lost for four hundred years. Machu Picchu was built on a rock pinnacle three of whose sides drop vertically 2,000 feet into the rapids of the Urubamba River, traversable only over a vine suspension bridge, and whose fourth side rises abruptly into the Huayna Picchu peak. The city was accessible only by a narrow path cut into the cliff wall, where two men could stop an army. No military attack had depopulated Machu Picchu; the city is intact, save for the roofs, made of braided and colored thatching, which had rotted away. A great rock thrusts up high over all the buildings, it was carved in terraces and a plaza flattened on top about the intihuatana , an abstractly carved figure whose function—altar? idol? astronomical instrument?—cannot be determined, the sole one in all Peru which was not smashed by the Catholic priests. There were no statues or gold walls, though the tombs were intact and there were no signs of the deserted city having been

[*] He was led to the city by a Quechua boy whose father had gone to farm some of the still fertile terraces, a boy whose name Bingham did not record. Research on maps and archives revealed that the site had long been recorded with the local name Machu Picchu.

plundered. The contents of all the burial caves, mummies and ritual objects, as well as all the pottery and domestic implements found in Bingham's excavations in 1912 financed by the Yale Club were shipped off to New Haven, and nothing has been to this day returned.

But Machu Picchu could not be Vilcapampa. Its round Qorikancha temple is one of the greatest temples of any civilization, its walls and those of the city too perfectly carved to have been able to have been built in the thirty-six years during which the last four Incas survived after the fall of Qosqo. As the conquistadors were able to obtain, by torture, complete information of all the citadels of the Inca empire, it is almost certain that Machu Picchu had been depopulated and its very location effaced from the memory of the quipucamayus , the Inca state chroniclers, by the time of the Spanish conquest of Tawantinsuyu. There are no inscriptions, no carved reliefs on these walls.

Bingham paid great attention to the cracked and crystallized great rock upon which the Qorikancha temple was built, effects which could only have been caused by enormous heat. He searched in vain for traces of ashes of sacrificial fires. Archeologist Marino Orlando Sánchez Macedo[1] has recently concluded that the gold-plated walls had attracted a catastrophic bolt of lightning, supreme evil omen for the Incas, and, after ritual purification of the site, the inhabitants abandoned it definitively, taking with them all its ritual treasures. Excavation of the burial caves had revealed there were twelve times as many women as men. One-sixth of these women were dwarfs. The mummies were embalmed with hieratic ritual objects: Machu Picchu was not a fortress but a sanctuary of priestesses and sorceresses. Most likely the six

hundred terraces on the cliffs above and below the city grew mainly coca, to supply the sacred rites of Qosqo.

An entire city whose discourse is irremediably irrational to us, bewitched signs, even if we could recover them unrecordable on our software, impermeable to us. Anyone in search of the world of the Incas can only contemplate the walls of Machu Picchu.