IV

Literary Responses to the Eighteenth-Century Voyages

Charles L. Batten, Jr.

By the expression "literary responses" in my title, I mean accounts written by travelers themselves. Although this study focuses on English travelers, I must stress that travel literature was a truly international genre during the eighteenth century: French and German voyages and travels usually appeared in English almost as quickly as they were initially published. Since these accounts are essentially nonfictional, they tend to receive short shrift from literary types—and I am the token literary type in this volume of essays. In focusing on the accounts of travelers themselves, my study is not , for example, going to be about how playwrights (like John Dryden) borrowed settings and names of characters from travelers, or how poets (like Samuel Taylor Coleridge) borrowed situations and descriptions from travelers, or how novelists (like Tobias Smollett) borrowed conflicts and narrative structures from travelers. Rather, my aim here is to look at the accounts of travelers as literature per se. Eighteenth-century critical opinion, as we shall see shortly, amply justifies this approach.

By the expression "eighteenth-century" in my title, I mean very roughly the hundred years that separate William Dampier's setting sail for Jamaica in 1679 (described at the very beginning of his New Voyage Round the World ) and the return to England of Captain James Cook's third voyage in 1779—alas without Captain Cook on board. At the beginning of this hundred-year period, the map of the world contained many blank areas, mainly in or adjoining the Pacific Ocean. When Dampier conducted his first voyage, "nearly half the surface of the globe we inhabit" was, in the words of Cook's editor John Douglas, "hid in obscurity and confusion."[1] Incidentally, the blank areas on the globe are where Jonathan Swift situated Lilliput, Brobdingnag, Laputa, Balnibarbi, Glubbdubdrib, Luggnagg, the land of the Houyhnhnms, and the like.

The reasons for these blank areas are quite simple: since 50 miles was the average day's sea journey, the time consumed in searching out "remote nations of the world"—to use Swift's expression—was immense, rather like trying to catch a dust mote floating in a not-so-pacific bathtub. Moreover, trade winds obliged most ships to follow roughly the same routes across the Pacific. Things began to change in 1699, when the British government put Dampier in charge of one of the first expeditions ever sent primarily to acquire new knowledge. On Dampier's first voyage, he was a privateer (to use the polite term), a pirate (to use the blunt one). On his second voyage, he was the leader of a scientific expedition. Things changed even more in 1763, when the Peace of Paris concluded the Seven Years' War and ushered in an unparalleled era of exploration and discovery. It removed the so-called legitimate motives for privateering and, in so doing, reduced the dangers of nonmilitary navigation. In the year following the Peace of Paris, England sent Captain John Byron to explore the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic and other archipelagoes in the Pacific; three years after the peace pact, Captain Samuel Wallis circumnavigated the globe; four years after the peace pact, Cook embarked on his first voy-

age. As the result of such undertakings—especially Cook's three voyages—the blank areas on the globe were reduced by 1784 to what John Douglas called "minutiae." It is tempting—though of course fruitless—to speculate where Swift would have had to locate Lilliput, Brobdingnag, Laputa, Balnibarbi, Glubbdubdrib, Luggnagg, and the land of the Houyhnhnms if he had written Gulliver's Travels after Cook's third voyage.

When I use the expression voyages of discovery, I primarily mean travels undertaken on ships aimed at discovering either new lands or new characteristics of previously discovered lands. That, after all, is the focus of this volume. Yet if we look—as I propose—at the literary responses to these voyages of discovery, we must avoid artificial distinctions based solely on subject matter. For the eighteenth-century Englishman, any foreign discovery necessarily involved some kind of sea voyage, at least until 1785 when the first balloon crossed the English Channel. And as is the case with Richard Lassels' Voyage of Italy (1670), the word "voyage" sometimes denoted travel in general rather than shipboard travel in particular. But more important there was little difference during the century concerning how an author wrote about discoveries made, for example, in far-off Tahiti and in nearby France. Daniel Defoe surely used techniques learned from travelers to distant lands when he wrote his Tour Thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724-1727).

I apologize for this lengthy definition of terms in my title. By way of extenuation, I can point out that Charles Darwin also had trouble with titles. It took him no less than four published tries to come up with The Voyage of the Beagle . His first title was the agonizingly ponderous Narrative of the Surveying Voyage of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle, Between the Years 1826 a 1836, Describing Their Examination of the Southern Shores of South America, and the Beagle's Circumnavigation of the Globe .

Samuel Johnson makes the following comment in his

advertisement to John Newbery's The World Displayed (1760-1761):

Curiosity is seldom so powerfully excited, or so amply gratified, as by the faithful relations of Voyages and Travels. The different Appearances of Nature, and the various Customs of Men, the gradual Discovery of the World, and the Accidents and Hardships of a naval Life, all concur to fill the Mind with Expectation and Wonder; . . . the Student follows the Traveller from Country to Country, and retains the situation of Places by recounting his Adventures.

This praise of voyages and travels has a curiously hollow ring to our modern ears. It sounds like a glorification of castor oil, or cold showers, or mastering classical Greek. Any teacher who has attempted to lead twentieth-century undergraduates through the intricacies of eighteenth-century travel accounts knows he has built the makings of a rebellion into his syllabus. Even Henry Fielding's Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon (1755), Tobias Smollett's Travels Through France and Italy (1766), and Dr. Johnson's own Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (1775)—by anyone's measure some of the most "literary" of the century's travel accounts—evoke boredom at best, outrage at worst, among most modern students.

But any of us who examines how eighteenth-century travel accounts have fared at the hands of critics and historians recognizes that a failure to appreciate them for what they are is scarcely an undergraduate phenomenon. Someone like Hans-Joachim Possin, for example, identifies what he calls "das Thema des Reisens in der englischen Literatur des 18. Jahrhunderts." According to Possin, the theme that runs through all eighteenth-century travel literature is that of "the exemplary quest" in which the hero or narrator searches "for possible ways and means of self-knowledge and self-realization." This quest involves a "dynamic and dialectic process of struggling between the idealistic yearnings of a passionate imagination and the realistic, empirical findings of a moralistically tempered

intelligence." And all of this is "cast into the narrative pattern of a journey." Consequently, such components of travel accounts as "style, plot, [and] the character of the narrator-traveler bear a remarkably close relationship" to those that occur in "strictly fictional" works.[2] Such a definition—which incidentally enables Possin to lump together such generically disparate works as Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress , Fielding's Tom Jones , Johnson's Rasselas , and Smollett's Travels —implies that the reader will encounter some rather exciting narrative and psychological material in travel accounts. From such a critical perspective, the travel account indeed seems virtually a subspecies of the Bildungsroman .

In a similar vein, Sondra Rosenberg claims that in form eighteenth-century voyages and travels most resemble picaresque novels:

Like the hero of that genre, the hero of the travel book is an outsider in the world in which he finds himself. He has no roots in the culture he is in. Both he and the picaro try to come to terms with the society they are in. For the picaro, coming to terms means being fully accepted by the society as a working, productive member of it . . . or, failing to do so, by dying. . . . For the hero of the travel book, coming to terms does not mean becoming part of the culture, but rather understanding it and de fining its limits. [3]

Such a view then leads Rosenberg to argue that Fielding's Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon must be at least partly a "parody of voyage literature"[4] since it is so boring and so unlike a picaresque novel.

I believe that Possin and Rosenberg are seriously mistaken and—more important—that their mistakes reflect the way many twentieth-century readers usually approach the kind of books that Dampier, Cook, and Hawkesworth wrote. Possin and Rosenberg are looking in the wrong places to locate the appeal of eighteenth-century travel accounts. In form, eighteenth-century voyages and travels

are neither Bildungsromanen nor picaresque novels. They lack psychological development and sustained narrative interest. To read them as novels is inevitably to read them as either failed novels or parodies.

My aim here is not to define the generic form of eigh-teenth-century travel accounts. I have attempted to do that elsewhere.[5] While they may look like autobiographies, their primary subject matter is the countries visited—not the experiences of the traveler. When a traveler mentions his experiences, they must always be subservient in importance to the countries being described. For the most part, a traveler's experiences enable him to organize his observations and reflections concerning the countries he visited. If a traveler relates too much about himself, he leaves himself open to charges that he is egotistical; if he relates too little about himself, he leaves himself open to charges that he never visited the countries he describes.

Nor is it my aim here to prove that travel accounts constituted one of the century's most popular literary genres—indeed, some have claimed they were second only to novels.[6] Others have satisfactorily performed that task.[7] A word of caution, however, is in order. This popularity scarcely means that the century unanimously approved of all voyages and travels. Readers often damned specific accounts as being dull, egotistical, trivial, repetitive, plagiarized, dishonest, and the like. (Fielding, indeed, claimed that virtually all travel accounts were deficient in their execution.) But while the century may have damned particular accounts, it almost unanimously approved of their general literary goals. The major exception to this approval is Jonathan Swift, but more about him later.

My aim here is to argue the following thesis: central to most eighteenth-century accounts of voyages and travels—and to the popularity they enjoyed—is the concept of the Scientific Hero. The hero, however, is not in the travel accounts—as Possin and Rosenberg would have it. If the traveler described himself as a hero per se, his account

would be dismissed as a novel, as a romance, or as an act of pure egotism. As I argue in the first part of this study, the "heroic" dimension of the eighteenth-century traveler is largely supplied by extraliterary means. It comes not so much from what the traveler says about himself in his account as it does from the way eighteenth-century readers felt about travelers in general and from what they discovered by reputation concerning certain travelers in particular. As I shall argue in the second part of this essay, the "scientific" dimension of the traveler is largely supplied by literary means. It comes from how the traveler experimentally examines the various characteristics of the countries he describes. Finally, by way of conclusion, I shall suggest some ways in which this concept of the Scientific Hero might help us better understand Swift's goals in Gulliver's Travels . Most of the century glorified the Scientific Hero; Swift satirized him.

The Traveler As Hero

The eighteenth century was by all accounts the age of travel, and the traveler tended to be one of the century's cultural heroes. Travel often served as a rite of passage for the Englishman. Throughout the century, completion of the Grand Tour gave him credentials as a man of learning and cultural polish. And toward the end of the century, completion of the Petit Tour—that is, travels in England and sometimes in Scotland and Wales—increasingly gave him credentials as a man of taste and sensitivity for nature. Chevalier Dennis de Coetlogon seems not to have indulged in hyperbole when he claimedn 1795 that "the English Nation is more inclined to Travelling than any other in Europe ."[8] The English "Milord" of the eighteenth century was as ubiquitous as today's Middle Eastern sheik or Japanese businessman, and most foreigners seemed to think that he carried almost as much money with him.

Figure 4.1.

William Bunbury: Tour to Foreign Parts (1778). (Figures 4.1-4.4

reproduced courtesy of the University Research Library,

University of California, Los Angeles.)

The century's satirists could scarcely have made such fun of travelers if traveling had not been so popular and had not served such an important cultural function. William Bunbury's Tour to Foreign Parts shows a young Englishman on his Grand Tour in France (see Figure 4.1).[9] The tutor (or rather the "bear-leader," as wags liked to call him) stands behind him. The proprietor of La Grenouille Traiteur—or "The Inn of the Treacherous Frog"—stands in front of him, bill of fare extended. One wonders if chicken or cat will grace the young gentleman's dinner table. In any event, his vacant smile gives us no doubt concerning the amount of learning and cultural polish he will acquire on his Grand Tour. In a similar satiric vein, Thomas Rowlandson's Dr. Syntax Copying the Wit of the Window shows an Englishman gathering supposedly valuable information while on his Petit Tour.[10] This information involves

romantic verses, like the following ones, scratched on the windows of inns:

I hither came down

From fair London town

With Lucy so mild and so kind;

But Lucy grew cool,

And call'd me a fool,

So I started and left her behind.

But the eighteenth-century Englishman's itch for travel extended far beyond the confines of the Grand or Petit Tour. The amateur Went to France or rural England; the professional went to the Cape of Good Hope or Java. He might be a seaman, a merchant, a missionary, or—especially toward the end of the century—a naturalist. These travelers to far-off regions tended to suffer less severe treatment from satirists. Their tales might certainly be doubted, but they were more often lionized by polite society.

A brief look at Captain Cook shows the extent to which a traveler could become a cultural hero—imbued with personality traits and heroic actions far transcending anything described on the pages of his journals. To be certain, Cook had the good sense to be murdered by a South Sea islander: dead men make better myths than live ones. Cook's death elevated him to the heights of national hero, and there was no need to remind oneself of the petty reasons for Cook's argument with the natives. But better yet, Cook's subsequent apotheosis elevated him to the status of a secular god. Figure 4.2 is based on a backdrop De Loutherbourg constructed for The Death of Captain Cook; A Grand Serious-Pantomimic-Ballet . . . As Performed at the Theatre-Royal, Covent Garden (1789).[11] In this popular pantomime, Cook's death results from a love triangle among the natives in which he tries to operate as a kind of divine mediator. And to move from the sublime to the mundane, by the beginning of the nineteenth century Englishmen

Figure 4.2.

De Loutherbourg: The Apotheosis of Captain Cook (broadside, 1794).

could purchase porcelain figurines of Captain Cook to decorate their tables and mantles.

But Cook, of course, was a cultural hero long before his death. The force of his personality and the exciting stories he told in person (rather than on the pages of his journal) were enough to make a strong impression on his hearers. James Boswell, for example, reports Cook's dinner conversation in the following fashion:

He gave me a distinct account of a New Zealander eating human flesh in his presence and in that of many more aboard, so that the fact of cannibals is now certainly known. We talked of having some men of inquiry left for three years at each of the islands of Otaheite, New Zealand, and Nova Caledonia, so as to learn the language and . . . bring home a full account of all that can be known of people in a state so different from ours.

On the basis of such tales, Boswell confesses he "felt a stirring . . . to go upon such an undertaking." But he then added, in typical Boswellian fashion, that he would sail with Cook if the government granted him "a handsome pension for life."[12]

As a result of such "public appearances," travelers often imparted a different kind of information than was contained on the pages of the accounts they published. Thus it was not uncommon during the eighteenth century to read between the lines, filling in facts supplied elsewhere by the traveler at some dinner party or by common rumor. John, Durant Breval earned a place among Alexander Pope's dunces for telling stories of how he had helped a nun escape from a convent in Milan, where she was confined against her will. But no such story appears in Breval's Remarks on Several Parts of Europe (1726, 1738). While a tale like that would increase a traveler's fame at dinner parties and in coffee houses, it would scarcely serve as a decorous or relevant topic to be treated in a published travel account. In a similar vein, James Bruce got himself into serious trouble by telling anecdotes prior to publishing his

Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (1790). After journeying through Abyssinia in search of the Nile's headwaters, Bruce greeted London society in 1774 with the seemingly preposterous claim that he had eaten raw meat cut from live cows. For many hearers, this true story sounded too much like a lie, the kind that Psalmanazar had told at the beginning of the century. And if Bruce lied about eating raw flesh, perhaps he even lied about traveling to Abyssinia.

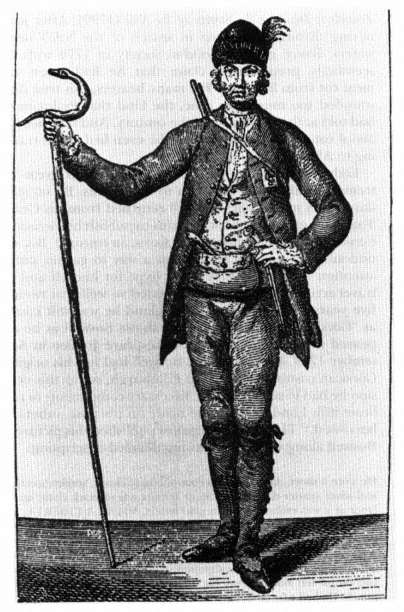

Eighteenth-century travelers often went to great extremes to call public attention to themselves. By no standard a shy man, James Boswell returned from his Grand Tour with many stories, with plans to publish his Account of Corsica (1768), and with a flashy Corsican costume. Boswell undoubtedly saw this costume as a way to garner public attention—a kind of advertising hype for himself and his travel account. Indeed, he succeeded so well that twenty-five years after his return to England he was still known as "Corsica Boswell." Figure 4.3 shows Boswell as he appeared at Garrick's famous Shakespeare Jubilee in September 1769. Unfortunately, Boswell had left his original Corsican costume at home in Edinburgh, so for this occasion he had to search out the necessary components to replicate it in London. Some he made on purpose, others he borrowed.[13] The London Magazine published this picture of Boswell along with the following detailed description:

He wore a short, dark-coloured coat of coarse cloath, scarlet breeches, and white spatter-dashes, his cap or bonnet was of black cloth; on the front of it was embroidered, in gold letters, VIVA LA LIBERTA; and on one side of it was a handsome blue feather and cockade, so that it had an elegant, as well as a warlike appearance. On the breast of his coat was sewed a Moor's head, the crest of Corsica surrounded with branches of laurel. He had also a cartridge-pouch, into which was stuck a stiletto, and on his left side a pistol was hung from the belt of his cartridge-pouch. He had a fusee slung across his shoulder, wore no powder in his hair, but had it platted, at its full length, with a knot of blue ribbon at the end of it. He had by way of a staff a very curious vine. . . He wore no mask, saying it was not proper for a gallant Corsican.[14]

Figure 4.3.

James Boswell in the London Magazine (Sept. 1769), p. 455.

Chances are that Boswell wrote this detailed description specifically for inclusion in the London Magazine .

When Pierre Maupertuis returned from his expedition to Lapland in 1736, he brought back his heavy fur clothing but one-upped Boswell by also bringing back two Lapp girls. Maupertuis's Figure of the Earth (1738) never mentions these girls.[15] After all, they had nothing to do with the goal of his expedition, which was to measure the length of a degree along the meridian in an attempt to determine whether Newton had been correct in claiming the earth was flattened at the poles. Indeed, Maupertuis refuses even to describe his shipwreck on the way home because it does not "belong to the present Subject" of his book.[16] Maupertuis undoubtedly had many reasons for transporting these girls to Paris. They were curiosities, much like the inscriptions and antiquarian artifacts brought back by travelers to Italy and much like the plants and insects brought back by travelers to the New World. But they also helped make Maupertuis famous. He might be a rather anonymous person in his travel account, but he had no intention of remaining anonymous in the salons of Paris. Voltaire originally celebrated Maupertuis and his fellow voyagers by saying:

Heroes of science, hail! like Argonauts ye brave

The dangers of far climes, the perils of the wave;

Your measurements exact and arduous give birth

To the true knowledge of the figure of the earth.[17]

In a subsequent edition of this poem, Voltaire changed his tune by trivializing Maupertuis's achievements: a "measurement, Lapp girls, and other curious things."[18]

And, finally, when Dampier brought back Prince Giolo (or Prince Jeoly) from his first voyage, his main purpose seems to have been merely financial: he would earn money displaying this tattooed South Sea islander much as Glumdalclitch's father made money showing Gulliver in Brobdingnag. Dampier's descriptions of Giolo in A New Voyage

are straightforward, matter-of-fact, and unromantic. By contrast, the Londoners to whom Dampier sold Giolo came up with advertising copy that could serve as the basis of an exciting romance. A broadside owned by the Clark Library claims that Prince Giolo was shipwrecked in a violent tempest, taken prisoner on the coast of Mindanao, and then sold to foreigners bound for Europe. It tells us that except for face, hands, and feet, Giolo's entire body is painted. On his back parts, for example, could be seen "a lively representation of one quarter part of the World" with "the Artick and Tropic Circles center[ed] in the North Pole of his Neck." Why go to the expense of sending mariners to chart the Pacific when it had already been done for us on Giolo's back? This broadside also tells us that the painting on Giolo's body made him invulnerable to "all sorts of the most venomous, pernicious Creatures [that] can be found; such as Snakes, Scorpions, Vipers, and Centapees."[19]

This is the stuff romances are made of. But Dampier's New Voyage —like most eighteenth-century travel accounts —is not the stuff romances are made of unless one reads between the lines. And to read between the lines requires the reader's imaginative involvement—an involvement that glorifies the traveler and, I think, projects the reader into the traveler's situation.

The Traveler As Scientist

But why, aside from his own self-advertising, did the eighteenth-century traveler—and by extension the eighteenth-century travel writer—develop into this kind of cultural hero? After all, travelers are no longer cultural heroes, unless they happen to find themselves in novel conveyances like space capsules circling the moon or one-man sailboats circling the globe. And travel accounts no longer form a major branch of literature, except in the eyes of a very few readers, most of whom happen to be planning their own trips.

Voyages of discovery—at least as conceived of in the eighteenth century—are but rarely possible in the twentieth century. Going to Anacapa Island recently, my family found coreopsus plants, Indian middens, and a butterfly that lives nowhere else in the world. We saw exciting things, but we discovered nothing. Others had already seen, described, and explained everything we encountered. But had we been an eighteenth-century family, even with our deficient twentieth-century educations, we could have discovered something on Anacapa and, better yet, published a description of it. If the eighteenth century is the age of traveling for discovery, the twentieth century is—alas—the age of tourism. Discovery has largely disappeared; sightseeing has taken its place.

Essential to discovery in any age is not only the possibility for true novelty but also a scientific spirit, the kind that Jean d'Alembert describes as ruling his century:

Our century is called . . . the century of philosophy par excellence. . . . If one considers without bias the present state of our knowledge, one cannot deny that philosophy among us has shown progress. Natural science from day to day accumulates new riches. . . . The true system of the world has been recognized, developed, and perfected. . . . In short, from the earth to Saturn, from the history of the heavens to that of insects, natural philosophy has been revolutionized.[20]

In a similar vein, James Keir claimed in 1789 that "the diffusion of a general knowledge, and of a taste for science, over all classes of men, in every nation of Europe, or of European origin, seems to be the characteristic feature of the present age."[21]

"To know how to travel well," said Chevalier de Coetlogon, is "a very great Science" and "in great measure the Source of all other Sciences."[22] One of my colleagues at UCLA has claimed that during the hundred years between 1680 and 1780, science and literature were as close in their ultimate aims as they have ever been.[23] This is especially true for eighteenth-century travel literature. The scientific spirit that sent travelers in search of new discoveries and

inspired them to write about those discoveries also sent readers in search of new travel accounts to peruse. And these readers were not merely ones we would call "scientific types" in the twentieth century. William Wordsworth, for example, wrote the following request to James Webbe Tobin in 1798:

I have written 1300 lines of a poem [i.e., The Recluse ] in which I contrive to convey most of the knowledge of which I am possessed. My object is to give pictures of Nature, Man, and Society. Indeed I know not any thing which will not come within the scope of my plan. . . . If you could collect for me any books of travels you would render me an essential service, as without much of such reading my present labours cannot be brought to a conclusion.[24]

Wordsworth is scarcely famous for his unbridled love of all things scientific; for him, "we murder to dissect." Yet Wordsworth's letter implies that in subject matter and ultimate goal—if not in form—little difference existed between his projected poem and the travel accounts he was planning to read.

It would be folly to claim that the scientific mood of the eighteenth century was caused by the Royal Society. But the Royal Society certainly captured this mood and in so doing helped propagate it. A major part of the society's work involved investigating foreign lands. As Thomas Sprat indicates in his famous History (1667), the Royal Society undertook a four-part approach to such research, employing fellows to examine treatises already written concerning foreign countries, to interview "seamen, travellers, trades-men, and merchants," to compose questions that remained to be answered about foreign countries, and to send these questions to correspondents in the remote corners of the world.[25] Indeed, the Royal Society's thirst for discovering foreign parts smacked of enthusiasm: "Almost as much space of Ground remains still in the dark, as was fully known in the times of the Assyrian , or Persian Monarchy . So that without assuming the vain prophetic spirit . . . we may

foretell, that the Discovery of another new World " is still at hand.[26] To achieve these discoveries, the Royal Society was not slow in publishing its "Directions for Sea-men, Bound for Far Voyages." These initial directions largely involved straightforward record keeping. They instructed travelers to measure depths, register weather, plot coastlines, collect seawater, and the like. The purposes for such directions were similarly straightforward: to attain its ends, the Royal Society must "study Nature rather than Books , and from the Observations, made of such Phaenomena and Effects She [i.e., Nature] presents, to compose such a History of Her, as may hereafter serve to build a Solid and Useful Philosophy upon."[27] The Royal Society expanded these directions, before long issuing specific inquiries for travelers bound to such places as Suratte, Persia, Virginia, the Bermudas, Guiana, Brazil, and Turkey.[28] And in the spirit of the Royal Society, that archdeist John Toland published a series of "Queries fit to be sent to any curious and intelligent Christians, residing or travelling in Mahometan countries; with proper directions and cautions in order to procure satisfactory answers."[29]

Even in their most superficial characteristics, many eighteenth-century travel accounts display a fairly obvious influence by the Royal Society. Dampier's New Voyage was dedicated to the Royal Society—something that Swift could scarcely have failed to notice. Cook's voyages were sent out by the Royal Society. William Halifax's travel account was published in the society's Transactions . Smollett's Travels contains a register of the weather—the kind of record the Royal Society had requested travelers to keep as early as 1666.[30] Addison's Remarks on Italy contains acoustical experiments conducted in the neighborhood of Milan—the kind of experiments the Royal Society liked to print in its Transactions . This list could easily continue.

The scientific spirit meant that travelers investigated the entire range of nature: they looked for and attempted to describe anything that was not already known involving in-

animate nature, plants, animals, and men. The title page of Dampier's New Voyage (see Figure 2.1) proclaims that it describes such disparate subjects as "Soil, Rivers, Harbours, Plants, Fruits, Animals . . . Inhabitants . . . Customs, Religion, Government, Trade, &c." Similarly, the title page of Smollett's Travels promises observations on "Character, Customs, Religion, Government, Police, Commerce, Arts, and Antiquities" with "a particular Description of the Town, Territory, and Climate of Nice."

The eyes of travel writers were on the physical representations in front of them, rather than on the classics or the Bible.[31] At least implicitly, travelers found themselves—whether they knew it or not—on the Moderns' side in the old Ancients versus Moderns dispute.[32] Their appeal was to experience, not authority. As the English editor of Anders Sparrman's Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope said in 1785, "every authentic and well written book of voyages and travels is, in fact, a treatise of experimental philosophy."[33]

The scientific goals of travelers and travel writers tended to be practical or theoretical, or in some cases both. The practical ones involved promoting trade, colonizing foreign lands, discovering new foods, finding useful minerals, learning new crafts, and the like. It is in this vein that Dampier claims he had "a hearty Zeal for the promoting of useful knowledge, and of any thing that may never so remotely tend" to his country's "advantage."[34] Travelers with a theoretical goal tended to assume with Pope that all of nature (be it inanimate, vegetative, animal, or human) is essentially uniform: "All Nature is but Art unknown to thee." As Hume pointed out, "Should a traveller . . . bring us an account of men, wholly different from any with whom we were ever acquainted . . . we should immediately prove him a liar, with the same certainty as if he had stuffed his narrative with stories of centaurs and dragons, miracles and prodigies."[35] Such a uniform view of nature does not mean the traveler should stay at home; rather it means that he should search out new bits of information that can

modify his larger view of nature. Although nature does not change, man's view of it does. And for this reason the century's great thinkers—men like Adam Smith, David Hume, and John Locke—combed travel accounts to support the theories they were developing.

Travel accounts thus served as storehouses for vast amounts of information. Some travelers seemed largely happy with collecting new information; others seemed primarily interested in synthesizing and explaining the information they collected. The first group focused on what Locke called "observations," the second on what he called "reflections." The great collections of travels—especially the Churchills'—served as forerunners of the encyclopedias.[36] And in an age when indexes were rare, travel accounts quite frequently contained extremely thorough ones.

While eighteenth-century travelers looked for anything new in the wide range of nature, their scientific investigations in such areas as geology and human nature posed some of the strongest challenges to conventional thinking. (England had to wait until the nineteenth century for Darwin's investigations to pose similar challenges to its views on flora and fauna.) In dealing with both geology and human nature, travel writers tended to be experimental philosophers; in so doing, they captured the scientific spirit of the century and the scientific interests of its readers.

The Scientific Approach to Geology

Patrick Brydone's Tour Through Sicily and Malta (1773) was one of the century's most popular travel accounts. Roughly a quarter of the way through his Tour , Brydone begins his description of Mount Etna, a description that incidentally struck most eighteenth-century reviewers as the most interesting part of his book. At the base of Etna, a Signor Recupero led Brydone and his fellow travelers to a deep well

where they could observe many layers of lava, each covered with a considerable amount of soil. By examining these layers, this clergyman had reasoned as follows: "If it requires two thousand years or upwards, to form but a scanty soil on the surface of a lava, there must have been more than that space of time betwixt each of the eruptions which have formed these strata." Counting these strata, Recupero had calculated that lava had been flowing from Etna for at least fourteen thousand years.

While this may strike us as good scientific reasoning, Brydone and Recupero both knew that it flew in the face of Archbishop Ussher's calculation that the world began in the year 4004 B.C. More important, Ussher had based his calculation on biblical rather than geological inquiry. Thus Brydone hastens to add: "Recupero tells me he is exceedingly embarrassed, by these discoveries. . . . That Moses hangs like a dead weight upon him, and blunts all his zeal for inquiry. . . . What do you think of these sentiments from a Roman Catholic divine?—The bishop . . . has already warned him to be upon his guard: and not to pretend to be a better historian than Moses."[37] Here Brydone seems primarily interested in poking fun at those silly Italian Roman Catholics. Elsewhere in his Tour , however, he comes out firmly on the side of Recupero's scientific method. Thus while ascending Etna, Brydone marvels at how smoke and heat are still evident from an eruption that occurred some four years earlier. This leads him to a scientific reflection: "There is an easy method of calculating the time that bodies take to cool:—Sir Isaac Newton, I think, in his account of the comet of 1680, supposes the times to be the squares of their diameters; and finding that a solid ball of metal of two inches, made red hot, required upwards of an hour to become perfectly cold, made the calculation from that to a body of the diameter of the earth, and found it would require upwards to twenty thousand years."[38]

In calculating that the world is at least twenty thousand years old—and not six thousand according to Ussher—

Brydone gets himself into serious trouble with some of his orthodox English readers. Johnson and Boswell both found fault with its "antimosaical" attitudes; Johnson thought Brydone would have been a better travel writer if he had been "more attentive to the Bible."[39] But that would have been fundamentally antithetical to the scientific spirit of Brydone's account.

The Scientific Approach to Human Nature

Investigations by eighteenth-century travel writers into the science of human nature are clearly more typical, far-reaching, and influential than those into geology. Their research into human nature marks the beginnings of modern social sciences. As Peter Gay has pointed out, "Whether realistic, embroidered, or imaginary, whether on ship or in the libraries, travel was the school of comparison, and travellers' reports were the ancestors of treatises on cultural anthropology and political sociology. It led to the attempt on the part of Western man to discover the position of his own civilization and the nature of humanity by pitting his own against other cultures."[40] The eighteenth-century travel account thus served as a "museum, in which specimens of every variety of human nature" were studied.[41] This museum, however, could always be misused. Dr. Johnson, for example, attacks Montesquieu for supporting his strange opinions by describing practices "of Japan or of some other distant country, of which he knows nothing."[42]

Some travelers spent their efforts attempting to define national characteristics. This was especially true for travelers on the Grand Tour, from whom we typically learn that Englishmen are serious and morose, Scotsmen proud and overbearing, Irishmen fortune-hunters, Frenchmen fops, Spaniards grave, Russians bearish, Italians effeminate, and the like.[43] And it is in this tradition that Smollett

encapsulates his experiments with French human nature in the following splenetic passage from his Travels Through France and Italy :

If a Frenchman is admitted into your family, and distinguished by repeated marks of your friendship and regard, the first return he makes for your civilities is to make love to your wife, if she is handsome; if not, to your sister, or daughter, or niece. If he suffers a repulse from your wife, or attempts in vain to debauch your sister, or your daughter, or your niece, he will, rather than not play the traitor to his gallantry, make his addresses to your grandmother, and ten to one, but in one shape or another, he will find means to ruin the peace of a family, in which he has been so kindly entertained.[44]

Travelers to places farther away than Italy and Spain tended to focus their scientific attention on more generalized questions concerning human nature. As Pope said, "The proper study of Mankind is Man." In so doing, they often tried to confirm, or in some cases reject, two of the century's more common myths: the Noble Savage and the Chinese Sage.

Omai was one of the eighteenth century's most noble savages. He came to England on board Captain Furneaux's ship after Cook's second voyage. London fell in love with Omai: He was genteel, polite, likable, and could even beat Giuseppe Baretti at chess. To top it all off, he came from the South Seas where summer was perpetual, sex spontaneous, and hard work unnecessary.

Here is the stuff of romance, but here too is the stuff of scientific argument. What is man? Is he essentially good, as suggested by popular views of Omai? Or is he essentially bad, as suggested by orthodox Christian thought? The argument between Shaftesburians and Hobbesians entered the pages of virtually every travel account dealing with the South Seas. If Western man is evil, why is that so? Denis Diderot's Supplement to Bougainville's Voyage suggested that Western society, and especially Christian sexual morality, was to blame. Dr. Johnson, of course, said poppycock.[45]

The Chinese Sage posed similar problems. While the Noble Savage was uneducated and simple, the Chinese Sage was enlightened and sophisticated. Moreover, his enlightenment came from Confucius, who in many respects sounded suspiciously like Jesus. As a myth, the Chinese Sage certainly dates back to the Jesuit missionaries who tried to convert China using what the eighteenth-century Englishman saw as a clever brand of natural religion. Jesuit failures dated from the intervention of the pope in such free thought. In any event, by the time Johnson translated Father Jerome Lobo's Voyage to Abyssinia in 1735, the concept of the Chinese Sage had become so standard that Johnson could show his orthodox credentials by claiming that his readers would find on his pages no "romantic absurdities" such as "Chinese perfectly polite and completely skilled in all sciences."[46]

The discovery of this well-organized, advanced culture that knew nothing of the Christian message proved a trauma to the orthodox, a delight to the liberal. Leibniz, for example, could claim that the Chinese should send missionaries to instruct Europe in natural philosophy just as Europe had sent missionaries to instruct China in revealed religion.[47] And Hume could claim that the Chinese literati were "the only regular body of deists in the universe."[48] Some travelers and some philosophers using their accounts even went so far as to claim that the Chinese wrote a universal language, having escaped the curse of Babel.[49] For a century interested in all things universal, this was heady stuff indeed.

But in his investigations of the Noble Savage and the Chinese Sage, the Englishman ultimately was not concerned primarily with people who lived either in the South Pacific or the Orient. Rather, his main scientific interest lay in discovering something about himself—his own religion, society, sciences. Actual travelers who voyaged to the South Pacific and the fireside travelers who studied their accounts made comparisons between themselves and the people they either saw or read about. This was essential to

the scientific method. Dr. Johnson indeed sees this kind of comparison as a psychological justification for the popularity of travel literature. Our pleasure in reading about foreign countries, he says, "arises from a Comparison which every Reader naturally makes . . . between the Countries with which he is acquainted, and that which the author displays to his Imagination." As a consequence, this pleasure "varies according to the Likeness or Dissimilitude of the Manners of the two Nations. Any Custom or law unheard or unthought of before, strikes us with that surprise which is the effect of Novelty." By contrast, a custom or law similar to our own "pleases us, because it flatters our Self-love, by showing us that our Opinions are approved by the General Concurrence of Mankind."[50]

Such comparisons became the basis not merely for travel accounts but also for many of the century's satiric attacks on its own society. Non fictional travel accounts find Occidentals observing Orientals; fictional accounts often find Orientals observing Occidentals. In William Hogarth's Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism , which probably dates from 1759, we see an English church infected with religious frenzy. The clergyman thunders so loud he breaks the sounding board. His dislodged wig reveals a Jesuit in disguise; his opened gown reveals a harlequin in disguise. He is surrounded by fanatics like Mrs. Toft—who convinced the king's physician she had given birth to rabbits—and he is inspired by Wesley's sermons. The enthusiast at the far left shows that Jews are not immune to such frenzy. But outside the window we see the Turk calmly smoking his pipe. Nothing needs to be said; the comparison tells it all. Hogarth is not praising Islam; rather, he is attacking the excesses of Christianity.

A number of influences undoubtedly stand behind this picture. Hogarth may have been thinking of his friend Henry Fielding's latitudinarian sentiments. In Joseph Andrews , Parson Adams says that "a virtuous and good Turk " is "more acceptable in the sight of their Creator, than a

vicious and wicked Christian, tho' his Faith was as perfectly Orthodox as St. Paul's himself."[51] Hogarth may have been thinking of travel accounts like Sir Paul Rycaut's Present State of the Ottoman Empire (1668) and Lancelot Addison's West Barbary (1671), both of which attempt to dispel European views of Muslims as "Barbarous, Rude, and Savage."[52] Hogarth may have been thinking of satires like Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy or Persian Letters , both of which use a foreign traveler to dissect the follies of Parisian society. In any event, the inquisitive and irreverent attitude Hogarth expresses here is firmly in the tradition of the eighteenth-century scientific traveler.

Conclusion

Few readers have failed to see Gulliver's Travels as at least partially a parody of travel accounts. It opens with a satiric jab at Gulliver's "cousin Dampier," and Book II gives us an unintelligible passage of nautical jargon lifted from Samuel Sturmy's Mariners Magazine . In addition, few readers—especially since Marjorie Hope Nicolson's work on Book III—have failed to see that Gulliver's Travels is at least partially an attack on scientific experimentation. The Laputans are so wrapped up in the kind of speculative and experimental philosophy undertaken by the Royal Society that practical considerations have utterly left their heads.

To come up with easy answers concerning Gulliver's Travels is to miss the rich complexity of its satire and artistry. Nevertheless, if we regard Gulliver as a Scientific Traveler from the very beginning of Gulliver's Travels , we recognize two things: The parody of travel accounts is not restricted merely to individual passages, and the satire on the scientific method and its attendant reliance upon reason is not restricted merely to Books III and IV.

Swift's feelings concerning the Royal Society and the new experimental method must have been deep-seated

and in some ways prophetic. His Erastian views led him to regret that the Test Act did not apply to membership in the Royal Society. But more important, he must have seen travel accounts as instruments of the Royal Society. Relying as they did upon the scientific method, they would lead travelers and readers away from issues of morality and orthodoxy. Poring over the book of nature meant slighting the book of God. Swift might well have agreed with Henry Stubbe, who believed that "studying of natural philosophy and mathematics was a ready method to introduce scepticism at least, if not atheism, into the world."[53]

Gulliver is a Scientific Traveler throughout Gulliver's Travels . In Part I, he dissects Lilliputian society. We of course know that Lilliput equals England, but he does not. In Part II, he dissects Brobdingnagian society—comparing it with his own and finding it deficient. We of course know that Gulliver is to a large extent wrong. In Part II he also dissects giant wasps, and like a good member of the Royal Society he presents their stingers to Gresham College. He also carefully examines the breasts of the giant Brobdingnagian women. Figure 4.4 might be called a "centerfold" from the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society ;[54] it is meant to illustrate "An Account of a Very Sudden and Excessive Swelling of a Woman's Breasts." Chances are slight that this particular picture influenced Gulliver's Travels ; chances are great, however, that such preoccupation with scientific inquiry did.

So far I have suggested that Gulliver is first and foremost a Scientific Traveler. But unlike Dampier, Boswell, and Cook, he is no hero. As we saw in the first part of this study, the returning traveler was usually feted and dined; Gulliver, however, refuses to eat with humans unless his nose is stuffed with rue, lavender, or tobacco. In Gulliver's desire to become totally rational, he has become irrational. The scientific method of Gulliver—which most of the century's travel accounts glorified and which Swift detested—has to a large extent led to this insanity. Dampier and

Figure 4.4.

"An Account of a Very Sudden and Excessive Swelling of a

Woman's Breasts," Philosophical Transactions of the

Royal Society (17 Oct. 1669), plate facing p. 1041.

Gulliver both undertake voyages of discovery. Dampier is the age's Scientific Hero; Gulliver is Swift's Scientific Antihero.