PART ONE—

HUMANS AND ANIMALS

One—

Introduction

James J. Sheehan

In 1810, William Blake painted a picture that came to be known as Adam Naming the Beasts . Blake's portrait of the first man reminds us of a Byzantine icon of Christ: calm, massive, and immobile, Adam dominates the science. One of his arms is raised in an ancient gesture signifying speech, while around the other a serpent meekly coils. In the background, animals move in an orderly, peaceful file. Of course, we know the harmony depicted here will not last. Soon Adam and his progeny will lose their serence place in nature; no longer will they be comfortable in their sovereignty over animals or secure in the unquestioned power of their speech. Our knowledge of what is coming gives blake's picture is special, melancholy power.[1]

Since the Fall, man's place in nature has always been problematic. The problems begin with Genesis itself, where the story of creation is told twice. In the second chapter, the source of Blake's picture, God creates Adam and then all other living things, which are presented to man "to see what he would call them: and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof," The first chapter, however, has a somewhat different version of these events. Here man is the last rather than the first creature to be made; while still superior to the rest by his special relationship to God, man nevertheless appears as part of a larger natural order. A similar ambiguity can be found in Chapter Nine, which begins with a divine promise to Noah that all beings will fear him but then goes on to describe a covenant between God and Noah and "every living creature of all flesh." From the very start of the Judeo-Christian tradition, therefore, humanity is at once set apart from, and joined with, the realm of other living things.[2]

In Greek cosmology, humanity's relationship to animals was yet more

uncertain. Like the Hebrews, the Greeks seemed eager to establish human hegemony over nature. Animals sacrifice, which was so central to Greek religion, ritually affirmed the distinctions between humans and beasts, just as it sought to establish connections between the human and divine. Aristotle, the first great biologist to speculate about human nature, developed an elaborate hierarchy of living beings, in which all creatures—beginning with human females—were defined on a sliding scale that began with adult males. But the line between humanity and its biological neighbors was more permeable for Greeks than for Hebrews. Gods frequently took on animals form, which allowed them to move about the world in disguise. As punishment, humans could be turned into beasts. Moreover, a figure like Heracles, who was human but with supernatural connections, expressed his association with animals by wearing skins on his body and a lion's head above his own. And if animal sacrifice set humans and animals apart, there were other rituals that seemed to blur the distinction between them. Dionysus's Maenads, for instance, lived wild and free, consumed raw flesh, and knew no sexual restraint. By becoming like beasts, the Maenads achieved a "divine delirium" and thus direct contact with the gods.[3]

Christians saw nothing godlike in acting like a beast. To them, the devil often appeared in animal form, a diabolic beast or, as Arnold Davidson points out, in some terrible mix of species. Bestiality, sexual transgression across the species barrier, was officially regarded as the worst sin against nature; it remained a capital crime in England until the second half of the nineteenth century. Humanity's proper relationship to animals was that of master; beasts existed to serve human needs. "Since beasts lack reason," Saint Augustine taught, "we need not concern ourselves with their sufferings," an opinion echoed by an Anglican bishop in the seventeenth century who declared, "We may put them [animals] to any kind of death that the necessity either of our food or physic will require." Even those who took a softer view of humanity's relationship with animals believed that our hegemony over the world reflected our special ties to the creator. "Man not only rules the animals by force," the Renaissance philosopher, Ficino, wrote, "he also governs, keeps and teaches them. Universal providence belongs to God, who is the universal cause. Hence man who generally provides for all things, both living and lifeless, is a kind of God."[4]

Although set apart from the rest of creation by their privileged relationship with God, many Christians felt a special kinship to animals. As Keith Thomas shows in his splendid study, Man and the Natural Workd, so close were the ties of people to the animals among whom they lived that often "domestic beasts were subsidiary members of the human community." No less important than these pressing sympathies of everyday inter-

dependence were the weight of cultural habit and the persistent power of half-forgotten beliefs. Until well into the eighteenth century, many Furopeans viewed the world anthropomorphically, imposing on animals human traits and emotions, holding them responsible for their "crimes," admiring them for their alleged expressions of pious sentiment. Although condemned by the orthodox and ridiculed by secular intellectuals, belief in the spirituality of animals persisted. As late as the 1770s, an English clergyman could write, "I firmly believe that beasts have souls; souls truly and properly so-called."[5]

By the end of the eighteenth century, such convictions were surely exceptional among educated men and women. The expansion of scientific knowledge since the Renaissance had helped to produce a view of the world in which there seemed to be little room for animal souls. The great classification schemes of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries encouraged rational, secular, and scientific conceptions of the natural order. As a result, the anthropomorphic attitudes that had invested animals—and even plants—with human characteristics gradually receded; nature was now seen as something apart from human affairs, a realm to be studied and mastered with the instruments of science. Here is Thomas's concise summary of this process:

In place of a natural world redolent with human analogy and symbolic meaning, and sensitive to man's behavior, they [the natural scientists] constructed a detached natural scene to be viewed and studied by the observer from the outside, as if by peering through a window, in the secure knowledge that the objects of contemplation inhabited a separate realm, offering no omens or signs, without human meaning or significance.[6]

Within this new world, humans' claims to hegemony were based on their own rational faculties rather than divine dispensation. Reason became the justification as well as the means of humanity's mastery. Because they lack reason, Descartes argued, animals were like machines, without souls, intelligence, or feeling. Animals do not act independently, "it is nature that acts in them according to the arrangement of their organs, just as we see how a clock, composed merely of wheels and springs, can reckon the hours." Rousseau agreed. Every animal, he wrote in A Discourse on Inequality, was "only an ingenious machine to which nature has given sense in order to keep itself in motion and protect itself." Humans are not in thrall to their instincts and senses; unlike beasts, when nature commands, humans need not obey. Free will, intellect, and above all, the command of language gives people the ability to choose, create, and communicate.[7]

Not every eighteenth-century thinker was sure that humanity's unquestioned uniqueness had survived the secularization of the natural

order. Lord Bolingbroke, for example, still regarded man as "the principal inhabitant of this planet" but cautioned against making too much of humanity's special status.

Man is connected by his nature, and therefore, by the design of the Author of all Nature, with the whole tribe of animals, and so closely with some of them, that the distance between his intellectual faculties and theirs, which constitutes as really, though not so sensibly as figure, the difference of species, appears, in many instances, small, and would probably appear still less, if we had the means of knowing their motives, as we have of observing their actions.

When Alexander Pope put these ideas into verse, he added that the sin of pride that brought Adam's fall came not from his approaching too close to God but rather from drawing too far away from other living things:

Pride then was not, nor arts that pride to aid;

Man walk'd with beast, joint tenants of the shade;

And it was Pope who best expressed the lingering anxiety that must attend humanity's position between gods and beasts:

Plac'd in this isthmus of a middle state,

A being darkly wise and rudely great,

With too much knowledge for the sceptic side,

With too much weakness for the stoic pride,

He hangs between; in doubt to act or rest;

In doubt to deem himself a good or beast;

In doubt his Mind or Body to prefer;

Born but to die, and reas'ning but or err. . . .

Chaos of Thought and Passion all confus'd,

Still by himself abus'd, or disabus'd;

Created half to rise, and half to fall,

Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all;

Sole judge of Truth, in endless error hurl'd;

The glory, jest, and riddle of the world.[8]

In the second half of the eighteenth century, what Pope had once called the "vast chain of being" began to be seen as dynamic rather than static, organic rather than mechanistic. The natural order now seemed to be the product of a sosmic evolution that, as Kant wrote in 1755, "is never finished or complete." This meant that everything in the universe—from species of plants and animals to the structure of distant galaxies and the earth's surface—was produced by and subject to powerful forces of change. By the early nineteenth century, scientists had

begun to examine this evolutonary process in a systematic fashion. In 1809, Jean Baptiste de Lamarck published Philosophie zoologique, which set forth a complex theory to explain the transformation of species over time. Charles Lyell, whose Principles of Geology began to appear in 1830, doubted biological evolution but offered a compelling account of the earth's changing character through the long corridors of geologic time. Thus was the stage set for the arrival of Darwin's Origin of Species, by far the most famous and influential of all renditions of "temporalized chains of being." With this book, Darwin provides the basis for our view of the natural order and thus links eighteenth-century cosmology and twentieth-century evolutionary biology.[9]

Even before Darwin formulated his theory of natural selection, he seems to have sensed this his scientific observations would have powerful implications for the relationship between humans and animals. In a notebook entry of 1837, Darwin first sketched what would beocme a central theme in his life's work:

If we choose to let conjecture run wild, then animals, our fellow brethren in pain, diseases, death, suffering and famine—our slaves in the most laborious works, our companions in our amusements—they may partake [of] our origins in one common ancestor—we may be all netted together.

When he published Origin of Species twenty-two years later, he approached the matter delicately and indirectly: "it does not seem incredible" that animals and plants developed from lower forms, "and if we admit this, we must likewise admit that all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth may be descended from some one primordial form." In any event, he promised that in future research inspired by the theory of natural selection, "much light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history."[10]

The meaning of Darwinism for human history quickly moved to the center of the controversies that followed the publication of Origin . In 1863, T. H. Huxley, for example, produced Man's Place in Nature . Darwin himself turned to the evoluton of humanity in The Descent of Man, where he set out to demonstrate that "there is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties." Each of those characteristics once thought to be uniquely human turn out to be shared by higher animals, albeit in lesser degrees: animals cannot speak, but they do communicate; they are intellectually inferior to humans, but they "possess some power of reasoning"; they cannot work as we do, but they can even use tools in a rudimentary way. Darwin's discussion of animal self-consciousness is worth quoting at length, not simply because it conveys the flavor of his argument but also because it illustrates the

ease with which he slipped from talking about differences between humans and animals to describing differences between "races" of men.

It may be freely admitted that no animal is self-conscious, if by this term it is implied that he reflects on such points, as whence he comes or whither he will go, or what is life and death, and so forth. But how can we feel sure that an old dog with excellent memory and some power of imagination, as shewn by his dreams, never reflects on his past pleasures and pains in the chase? And this would be a form of self-consciousness. On the other hand, as Büchner has remarked, how little can the hard-worked wife of a degraded Australian savage, who uses very few abstract words, and cannot count above four, exert her self-consciousness, or reflect on the nature of her own existence.

Darwin carried on his examination of humans and animals in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Here he seeks to demonstrate that basic emotions have common origins and a biological base by pointing out the similarity of emotional expressions among human societies and between humans and animals. Like reason, language, and consciousness, emotions such as love, fear, and shame are not the sole and undisputed property of humanity.[11]

The research program suggested in this work on human and animal emotions was not immediately taken up by Darwin's many disciples. There were, to be sure, many who sought to apply Darwinism to human society, but they usually did so without a systematic examination of the resemblances between human and animal behavior. To social scientists influenced by Darwin, what mattered was less that people were animals than that they were still—in Harriet Ritvo's phrase—"the top animals," separated from the rest by what Dawwin himself had called man's "noble qualities" and "godlike intellect." Most of the natural scientists who followed Darwin turned in the opposite direction, away from humans toward other species with longer evolutionary histories and more accessible biological structures. As a result, empirical work on the connection between human and animal behavior, so central to Darwin's work on emotions, did not become an important part of his legacy until the second half of the twentieth century.[12]

The direct heirs of Darwin's research on human and animal emotion were scientists who studied behavioral biology, the discipline that would come to be called ethology. Although important research on ethology had been conducted during the 1920s and 1930s, the subject did not become prominent until the 1960s; in 1973, three leading ethologists shared the Nobel Prize. The new interest in ethology encouraged the publication of a variety of works of quite uneven quality, but all shared the conviction that studying the similarity of behavior existing across

animal species could yield important insights into the character of human individuals and groups. For example, Konrad Lorenz, a pioneer in the field and one of the Nobel laureates, maintained that, in both man and animals, aggressive behavior was instinctual. "Like the triumph ceremony of the greylag goose, militant enthusiasm in man is a true autonomous instinct: It has its own releasing mechanisms, and like the sexual urge or any other strong instinct, it engenders a specific feeling of intense satisfaction." Such deeply rooted instincts, ethnologists warned, will inevitably pose problems for, and set limits on, humans' ability to control themselves and their societies.[13]

By the 1970s, popular and scientific interest in ethnology had become enmeshed with a larger and more ambitious set of ideas and research enterprises conventinally called sociobiology. Edward O. Wilson, perhaps sociobiology's most vigorous exponent, describes it as the "scientific study of the biological basis of all forms of social behavior in all kinds of organisms, including man." Wilson began to define his view of the field in the concluding chapter of The Insect Societies (1971), which called for the application of his work on the population biology and zoology of insects to vertebrate animals. Four years later, he concluded Sociobiology: The New Synthesis with a chapter entitled "Man: From Sociobiology to sociology." This was followed in 1978 with the more popularly written Oh Human Nature, which examined what Wilson regarded as "four of the elemental categories of behavior, aggression, sex, altruism, and religion," from a sociobiological perspective. Wilson brought an ethnologist's broad knowledge of animal behavior to these subjects but added his own growing concern for the genetic basis of instincts and adaptations. This genetic dimension has become increasingly important in Wilson's most recent work.[14]

Sociobiology in general and Wilson in particular have been the subject of intense attacks from a variety of directions. In the course of these controversies, the term has tended to become a catchall for a variety of different developments in behavioral biology. Like many other controversial movements, sociobiology often seems more solid and coherent to its opponents, who can easily define what they oppose, than to its advocates, who have some trouble agreeing on what they have in common. It is worth noting, for example, that Melvin Konner, while sympathetic to Wilson in many ways, explicitly denies tht his own work, The Tangled Wing (1982), is sociobiology. But what Konner and the sociobiologists do share is the belief that most studies of human beings have been too "anthropocentric." If, as Wilson and others claim, "homo sapiens is a conventional animal species," then there is much to be learned by viewing the human experience as part of a broader biological continuum. Doing so will help us to understand what Darwin, in the dark passage at

the end of The Descent of Man, referred to as "the indelible stamp of his lowly origin" which man still carries in his body and what Konner, in a contemporary version of the same argument, calls the "biological constraints on the human spirit."[15]

We will return to some of the questions raised by sociobiology in the conclusion to this volume. For the moment, it is enough to point out that the conflicts surrounding it—illustrated by the works of Konner and Dupré in the following section—are new versions of ancient controversies. These controversies, while informed by our expandng knowledge of the natural world and expressed in the idiom of our scientific culture, have at thier core our persistent need to define what it means to be human, a need that leads us, just as it led the authors of Genexis, to confront our kinship with and differences from animals.

Two—

The Horror of Monsters*

Arnold I. Davidson

As late as 1941, Lucien Febvre, the great French historian, could complain that there was no history of love, pity, cruelty, or joy. He called for "a vast collective investigation to be opened on the fundamental sentiments of man and the forms they take."[1] Although Febvre did not explicitly invoke horror among the sentiments to be investigated, a history of horror can, as I hope to show, function as an irreducible resource in uncovering our forms of subjectivity.[2] Moreover, when horror is coupled to monsters, we have the opportunity to study systems of thought that are concerned with the relation between the orders of morality and of nature. I will concentrate here on those monsters that seem to call into question, to problematize, the boundary between humans and other animals. In some historical periods, it was precisely this boundary that, under certain specific conditions that I shall describe, operated as one major locus of the experience of horror. Our horror at certain kinds of monsters reflects back to us a horror at, or of, humanity, so that our horror of monsters can provide both a history of human will and subjectivity and ahistory of scientific classifications.

The history of horror, like the history of other emotions, raises extraordinarily difficult philosophical issues. When Febvre's call was answered, mainly by his French colleagues who practiced the so-called history of mentalities, historians quickly recognized that a host of historiographical and methodological problems would have to be faced. No one has faced these problems more directly, and with more profound results, than Jean Delumeau in his monumental two-volume history of fear.[3] But these are issues to which we must continually return. What will be required to write the history of an emotion, a form of sensibility, or type of affectivity, Any such history would require an investigation of

gestures, images, attitudes, beliefs, language, values, and concepts. Furthermore, the problem quickly arose as to how one should understand the relationship between elite and popular culture, how, for example, the concepts and language of an elite would come to be appropriated and transformed by a collective mentality.[4] This problem is especially acute for the horror of monsters, since so many of the concepts I discuss which are ncessary to out understanding of monsters come from high culture—scientific, philosophical, and theological texts. To what extent is the experience of horror, when expressed in a collective mentality, given from by these concepts? Without even attempting to answer these questions here, I want to insist that a history of horror, at both the level of elite concepts and collective mentality, must emphasize the fundamental role of description. We must describe, in much more detail than is usually done, the concepts, attitudes, and values required by and manifested in the reaction of horror. And it is not enough to describe these components piecemeal; we must attempt to retrieve their coherence, to situate them in the structures of which they are a part.[5] At the level of concepts, this demand requires that we reconstruct the rules that govern the relationships between concepts; thus, we will be able to discern the highly structured, rule-governed conceptual spaces that are overlooked if concepts are examined only one at a time.[6] At the level of mentality, we are required to place each attitude, belief, and emotion in the context of the specific collective consciousness of which it forms part.[7] At both levels, we will have to go beyond what is said or expressed in order to recover the conceptual spaces and mental equipment without which the historical texts will lose their real significance.

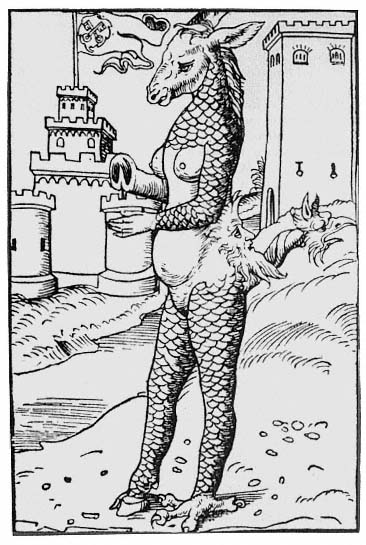

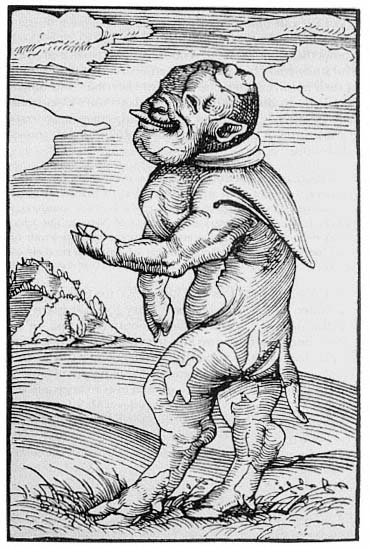

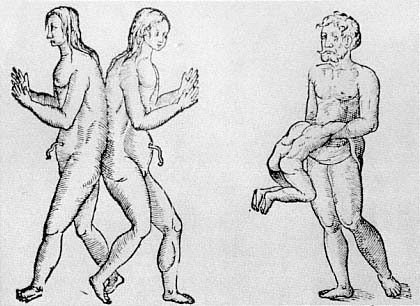

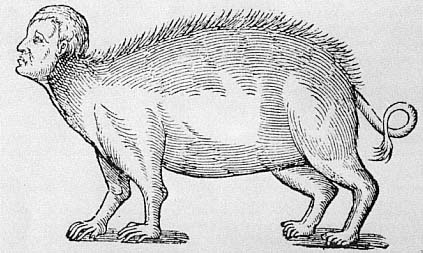

In 1523, Martin Luther and Phillip Melancthon published a pamphlet entitled Deuttung der czwo grewlichen Figuren, Bapstesels czu Rom und Munchkalbs czu Freyerbeg ijnn Meysszen funden .[8] It was enormously influential and was translated into French, with Calvin's endorsement, in 1557, and into English in 1579 under the title Of two wonderful popish monsters . The pamphlet consisted of a detailed interpretation of two monsters: a pope-ass, discussed mainly by Melancthon, supposedly left on the banks of the Tiber River in 1496, and a monk-calf, interpreted by Luther, that was born on December 8, 1522, in Freiburg (figs. 2.1, 2.2). Both of these monsters were interpreted within the context of a polemic against the Roman church. They were prodigies, signs of God's wrath against the Church which prophesied its imminent ruin. There were two dimensions to the Lutheran exegesis of these monsters.[9] On the one hand, there is a prophetic or eschatological dimension, only diffidently mentioned in this pamphlet, in which monsters and prodigies, as a general phenomenon, were taken to be signs of fundamental changes about to

Fig. 2.1.

The Pope-Ass.

affect the world. Often these signs were interpreted as nothing less than an announcement that the end of the world was at hand, and support for this prophetic interpretation was adduced by citing the Book of Daniel, a biblical text invokec by both Melancthon and Luther. The other dimension, which, following Jean Céard, we can call allegorical, is the one with which this pamphlet is most preoccupied. The allegorical exegesis of these monsters is intended to show that each monster has a very specific

Fig. 2.2.

The Monk-Calf.

interpretation that can be grasped because, in one way or another, it is represented before our eyes in the constitution of the monster itself; each monster is a divine hieroglyphic, exhibiting a particular feature of God's wrath. So, for instance, the pope-ass, according to Melancthon, is the image of the Church of Rome; and just as it is awful that a human body should have the head of an ass, so it is likewise horrible that the Bishop of Rome should be the head of the Church. Similarly, the overly

large ears of the calf-monk exhibit God's denouncement of the practice of hearing confessions, so important to the monks, while the hanging tongue shows that their doctrine is nothing but frivolous prattle.

A useful study could be made of the adjectives that appear in this text; in lieu of such a study, let me just note that "horrible" and "abominable" occur frequently in both Luther's and Melancthon's discussions, often modifying "monster." The mood of these adjectives is accurately conveyed in the translator's introduction to the 1579 English translation of the text. It begins:

Among all the things that are to be seen under the heavens (good Christian reader) there is nothing can stir up the mind of man, and which can engender more fear unto the creatures than the horrible monsters, which are brought forth daily contrary to the works of Nature. The which the most times do note and demonstrate unto us the ire and wrath of God against us for our sins and wickedness, that we have and do daily commit against him.[10]

John Brooke goes on to tell us that his motive for translating this pamphlet is the better "to move the hearts of every good Christian to fear and tremble at the sight of such prodigious monsters,"[11] and he warns his readers not to interpret these two monsters as if they were but fables. He closes his preface with the hope that, after reading this pamphlet, we shall "repent in time from the bottom of our hearts of our sins, and desire him [God] to be merciful unto us, and ever to keep and defend us from such horrible monsters."[12] He concludes with a few more specific remarks about the pope-ass and calf-monk addressed, and we shall not overlook the form of the address, "unto all which fear the Lord."

In order to better understand the preoccupation and fascination with monsters during the sixteenth century, a fascination fastened onto by Luther and Melancthon, whose text is fully representative of an entire genre, we must place these discussions within a wider context. As Jean Delumeau has argued in the second volume of his history of fear, it is within "the framework of a global pessimistic judgment on a time of extreme wickedness that one must place the copious literature dedicated to monsters and prodigies between the end of the fifteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth."[13] Sinfulness was so great that the sins of men extended to nature itself which, with God's permission and for the instruction of sinners, seemed to have been seized by a strange madness; the resulting monsters were to be understood as illustrations of these sins. Heresy and monsters were frequently linked during this period, both by reformers and Catholics alike. Prodigies were not only specific punishments for particular sins but they also announced greater punishments to come—war, famine, and perhaps even the end of the

world. This proliferation of monsters presaged a dark future explained by God's wrath at the increase of wickedness on earth.[14] Français Belleforest summarized the shared sensibility: "The present time is more monstrous than natural."[15]

To make as clear as possible the relationship between horror and monsters, I am going to focus primarily on one text, Ambroise Paré's Des monstres et prodiges, originally published in 1573 and frequently reprinted after that.[16] Since I am going to set the conceptual context for my discussion of Paré in a rather unconventional way, I want to state explicitly that a full comprehension of this treatise requires that it be placed in relation to other learned and popular treatises on monsters that both preceded and followed it. We are fortunate in this respect to have Céard's thorough treatment of Paré in his brilliant La Nature et les prodiges and in the notes to his critical edition of Des monstres et prodiges;[17] moreover, in the best English-language treatment of monsters, Katharine Park and Lorraine Daston have provided a three-stage periodization—monsters as divine prodigies, as natural wonders, and as medical examples for comparative anatomy and embryology—that is indispensable in helping us to understand shifts in the conceptualization and treatment of monsters from the Middle Ages to the eighteenth century.[18] Rather than summarizing the work of these scholars, I am going to turn to a different kind of text to prepare my discussion of Paré, namely, Thomas Aquinas's Summa Theologica .

Aquinas's Summa is not only the greatest work of genius produced by medieval moral theology but also a profound synthesis of previous work, coherently connecting doctrines, ideas, and arguments whose relationships had never been made very clear; moreover, the Summa also made conceptually determinate notions that had had a deep and wide-ranging significance in the Middle Ages but that had not really been approached with sufficient analytical precision. I am going to use one portion of the Summa as representative of medieval attitudes, attitudes that have lasted, in one form or another, for many subsequent centuries. I shall not address the question of the Summa 's originality in this area; suffice it to say that I believe that this is one place in which Aquinas gave a conceptually powerful formulation to a set of dieas that had been essential, even if not very precise, to most of medieval moral theology.

Part II of Part II, Questions 13 and 154, of the Summa Theologica deal with lust and the parts of lust, respectively. Aquinas begins, in Article 2 of Question 154, by considering the question of whether the venereal act can be without sin. He argues as follows: if the dictate of reason makes use of certain things in a fitting manner and order for the end to which they are adapted, and if this end is truly good, then the use of these things in such a fitting manner and order will not be a sin. Now the

preservation of the bodily nature of an individual is a true good, and the use of food is directed to the preservation of life in the individual. Similarly, the preservation of the nature of the human species is a very great good, and the use of the venereal act is directed to the preservation of the whole human race. Therefore, Aquinas concludes,

wherefore just as the use of food can be without sin, if it be taken in due manner and order, as required for the welfare of the body, so also the use of venereal acts can be without sin, provided they be performed in due manner and order, in keeping with the end of human procreation.[19]

He proceeds in the first article of Question 154 to differentiate six species of lust—simple fornication, adultery, incest, seduction, rape, and the vice contrary to nature—all of which are discussed in the remaining articles.

My concern is with the vices contrary to nature, which are discussed in Articles 11 and 12. In Article 11, he argues that this type of vice is a distinct species of lust, since it involves a special kind of deformity; vices contrary to nature are not only contrary to right reason, as are all the lustful vices, but are also "contrary to the natural order of the venereal act as becoming to the human race," which order has as its end the generation of children.[20] Aquinas distinguishes four categories of vice contrary to nature—bestiality, sodomy, which he interprets as male/male or female/female copulation, the sin of self-abuse, and not observing the natural manner of copulation. It is difficult to determine exactly what falls under this last category, but it is clear from II-II, Question 154, Article 12, Reply to Objection 4, that male/female anal and oral copulation are two of the most grievous ways of not observing the right manner of copulation.

In Article 12, Aquinas rank-orders, from worst to least worst, all of the lustful vices. He claims, first, that all four categories of vice contrary to nature are worse than any of the other vices of lust. So that bestiality, sodomy, not observing the natural manner of copulation, and self-abuse are worse, because of their special deformity, than adultery, rape of a virgin, incest, and so on.[21] Vices contrary to nature are worse in kind and not merely in degree than other lustful vices. Aquinas then goes on to rank-order the vices contrary to nature. The least bad of these vices is self-abuse, since the "gravity of a sin depends more on the abuse of a thing than on the omission of the right use."[22] Next worse is the sin of not observing the right manner of copulation, and this sin is more grievous if the abuse concerns the right vessel than if it affects the manner of copulation in respect of other circumstances. Third worse is sodomy, since use of the right sex is not observed. Finally, the most grievous of all the vices contrary to nature, and so the most grievous of any lustful vice,

is bestiality, since the use of the due species is not observed; moreover, in this instance, Aquinas explicitly cites a biblical text as support.[23] One final remark of Aquinas's must be mentioned before I turn to Paré. About the vices contrary to nature, from masturbation to bestiality, Aquinas writes,

just as the ordering of right reason proceeds from ne, so the order of nature is from God Himself: wherefore in sins contrary to nature, whereby the very order of nature is violated, an injury is done to God, the Author of nature.[24]

To act contrary to nature is nothing less than to act directly contrary to the will of God.

One may understandably be wondering how this discussion of Aquinas is relevant to the treatment of monsters, so let me turn immediately to Paré's Des monstres et prodiges . The preface to his book begins as follows:

Monsters are things that appear outside the course of Nature (and are usually signs of some forthcoming misfortune), such as a child who is born with one arm, another who will have two heads, and additional members over and above the ordinary.

Prodigies are things which happen that are completely against Nature, as when a woman will given birth to a serpent, or to a dog, or some other thing that is totally against Nature, as we shall show hereafter through several examples of said monsters and prodigies.[25]

Cérd has argued that Paré was somewhat indifference to the problem of precisely how one should distinguish monsters from prodigies. Monsters and prodigies did not constitute absolutely separate classes and during the successive editions of his book, Cérd things Paré became more and more convinced that the term "monster" was sufficient to designate all of these phenomena.[26] But however imprecise and unarticulated this distinction might appear, the idea that there was a separate class of phenomena, prodigies, that were completely against nature affected the language, attitude, and conceptualization with which Paré approached his examples.

In the first chapter of Des monstres et prodiges , Paré distinguishes thirteen causes of monsters, which causes, although not completely exhaustive, are all the ones he is able to adduce with assurance. Ten of these causes are straightforwardly natural causes; two, the glory of God and the wrath of God, are straightforwardly supernatural causes; and one, demons and devils, has a long and complicated classificatory history.[27] Briefly, to classify the products of demons and devils as a result of supernatural causes was to threaten to place the devil on a par with God, granting him the same powers to overturn the natural order that God

possessed. The possibility of such a theologically untenable position led to detailed discussions concerning the status of demonic causation; and as we can see from chapter 26 to 34, Paré fit squarely into these discussions, concerned both to grant the reality of the devil and yet to limit his powers. Of the two straightforwardly supernatural causes, Paré's threatment of the first, the glory of God, is exhausted by one example, the restoration of a blind man's sight by Jesus Christ, an example literally copied from Pierre Boaistuau's Histoires Prodigieuses , first published in 1560.[28]

The other supernatural cause, the wrath of God, is far more interesting for my purposes; most of the example produced by Paŕ to illustrate this category are of the same kind, and they are closely linked to the natural cause of the mixture or mingling of seed. I want to discuss these examples in detail in order to support some claims about the history of horror. But I should make one more preliminary remark. Paré, like virtually every writer during this period, had no intellectual difficulty in referring to both supernatural and natural causes; he felt no incompatibility in discussing these two types of cause together. Yet although God was always in the background of Des monstres et prodiges , by far the most space is devoted to natural causes, with God's explicit appearances being relatively few. This contrasts, for instance, with Jacob Rueff's De conceptu et generatione hominis , a book known to Paré, published in 1554 and for a long time the classic work on the problems of generation. Rueff also discussed supernatural and natural causes together, but in Book V of De conceptu , when he discusses monstrous births, Rueff considers them all as divine punishment, and their physical causes, however active, are almost ignored in favor of the evidence of the judgments of God. In Rueff's text, whether the physical or natural causes of the production of monsters, monsters are first of all punishments inflicted by God on sinners.[29] So Paré's book already demonstrates a shift of emphasis that makes his treatment of supernatural causes all the more interesting.

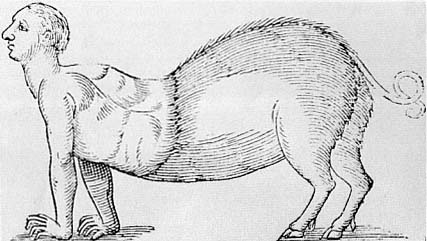

Paré's chapter on thw wrath of God opens with these words:

There are other creatures which astonish us doubly because they do not proceed from the above mentioned causes, but from a fusing together of strange species, which render the creature not only monstrous but prodigious, that is to say, which is completely abhorrent and against Nature. . . .

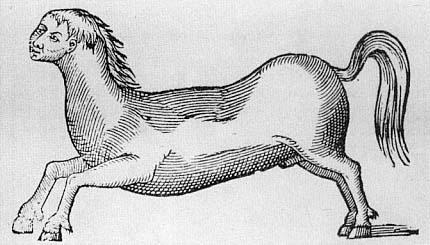

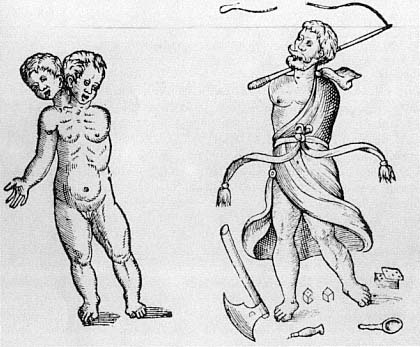

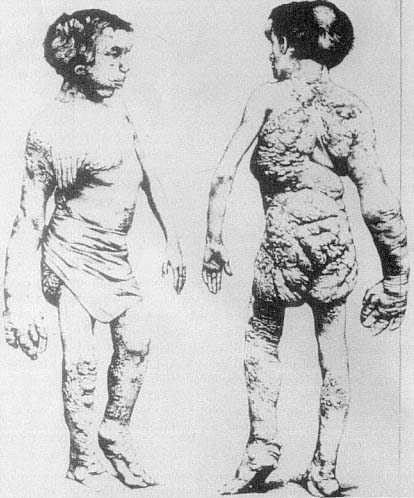

It is certain that most often these monstrous and prodigious creatures proceed from the judgment of God, who permits fathers and mothers to produce such abominations from the disorder that they make in copulation, like brutish beasts. . . . Similarly, Moses forbids such coupling in Leviticus (Chapter 16) (fig. 2.3).[30]

The creatures discussed in this chapter are produced by the natural cause of the fusing together of strange species, but, more important,

Fig. 2.3.

A colt with a man's head.

their, so to speak, first cause is God's wrath at the copulation between human beings and other species, a practice that is explicitly forbidden in Leviticus. The result is not only a monster but a prodigy, a creature that is contrary to nature and that is described as completely abhorrent.

If we turn to the chapter that treats the natural cause of the mixture or mingling of seed, we find Paré endorsing the principle that nature always strives to create its likeness; since nature always preserves its kind and species, when two animals of different species copulate, the result will be a creature that combines the form of both of the species.[31] The kind of naturalistic explanation exhibited in this chapter is, however, framed by crucial opening and closing paragraphs, which I quote at length. The chapter begins with this statement:

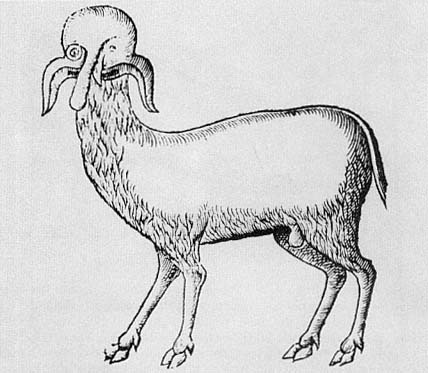

There are monsters that are born with a form that is half-animal and half-human . . . which are produced by sodomists and atheists who join together, and break out of their bounds contrary to nature, with animals, and from this are born several monsters that are hideous and very scandalous to look at or speak about. Yet the disgrace lies in the deed and not in words; and it is, when it is done, a very unfortunate and abominable thing, and a great horror for a man or woman to mix with and copulate with brute animals; and as a result some are born half-men and half-animals (figs. 2.4, 2.5).[32]

The chapter closes with this:

Now I shal refrain from writing here about several other monsters engendered from such grist, together with their portraits, which are so hideous and abominable, not only to see, but also to hear tell of, that, due to their

Fig. 2.4.

A monstrous lamb.

great loathsomeness I have neither wanted to relate them nor have them portrayed. For (as Boaistuau says, after having related several sacred and profane stories, which are all filled with grievous punishments for lechers) what can atheists and sodomists expect, who (as I said above) couple against God and Nature with brute animals?[33]

What I want to isolate is the conjunction of God's wrath at human disobedience of his laws (a supernatural cause) with the production of a creature contrary to nature, a prodigy, the reaction to which is horror; and, finally, I want to emphasized that the prime example for Paré of such human disobedience is bestiality. These features are in effect Paré's analogue to Aquinas's discussion in the Summa Theologica . For Thomas, there is a distinct category of lust, worse in kind than other species of lust, namely, just contrary to nature (remember that prodigies, being completely against nature, are worse in kind than monsters, being only outside the course of nature), the most grievous example of which is bestiality; moreover, when such sins are committed, an injury is done to God. Paré physicalizes this framework of concepts by exhibiting the consequence of such an injury to God; the resulting bestial creature is a sym-

Fig. 2.5.

A child, half dog.

bolic representation of God's wrath, and the reaction of horror we have to such hideous creatures is intended to remind us of, and to impress upon us, the horror of the sin itself. Thus, the special viciousness of sins contrary to nature extends to the creatures produced by these sins. Paré reserves his most charged language—horror, horrible, hideous, loathsome, abominable—for these creatures and the sins they represent.

The link between moral disorder and the disorder of nature was a constant theme during this period. It was widely believed that evil committed on earth could leave its mark on the structure of the human body.[34] And the way in which the physical form of the body gave rise to moral and theological questions went far beyond the case of prodigies. The issue of monstrous births as a whole raised practical problems for priests, since they had to decide whether any particular monstrous child was human, and so whether it should be baptized or not. There were, of course, disagreements about how to make these determinations, but the form of the body served as a guide to theological resolution. The kind of reasoning employed is well represented by Guido of Mont Rocher's Manipulus Curatorum Officia Sacerdotus of 1480:

But what if there is a single monster which has two bodies joined together: ought it to be baptized as one person or as two? I say that since baptism is made according to the soul and not according to the body, howsoever there be two bodies, if these is only one soul, then it ought to be baptized as one person. But if these are two souls, it ought to be baptized as two persons. But how is it to be known if there be one or two? I say that if there be two bodies, there are two souls. But if there is one body, there is one soul. And for this reason it may be supposed that if there be two chests and two heads there are two souls. If, however, there be one chest and one head, however much the other members be doubled, there is only one soul.[35]

I mention this example to indicate that Paré's use of the body as a moral and theological cipher is only a special instance, and not an entirely distinctive one, of a much more general mentalité.

What is most remarkable aobut Paré's book is that when he confines himself to purely natural causes, he employs the concept of monster exclusively (phenomena outside the course of nature) and not the concept of prodigy. Furthermore, the experience of horrror is absent from his descriptions. Horror is appropriate only if occasioned by a normative cause, the violation of some norm, as when the human will acts contrary to the divine will. The chapter that immediately follows Paré's discussion of the wrath of God concerns monsters caused by too great a quantity of seed. Compare its opening language with the language of the previous chapter already quoted.

On the generation of monsters, Hippocrates says that if there is too great an abundance of matter, multiple births will occur, or else a monstrous child having superfluous and useless parts, such as two heads, four arms, four legs, six digits on the hands and feet, or other things. And on the contrary, if the seed is lacking in quantity, some member will be lacking, [such] as feet or head, or [having] some other part missing (figs. 2.6, 2.7).[36]

Even Paré's discussion of hermaphrodites in chapter 6 bears no trace of horror, and we see that their formation is due entirely to natural causes,

Fig. 2.6.

Examples of too great a quantity of seed.

Fig. 2.7.

Examples of lack in the quantity of seed.

Fig. 2.8.

Hermaphrodites.

with no admixture of willful violation of a norm (fig. 2.8). Hermaphrodites are monsters, not prodigies, naturally explicable and normatively neutral.

If we read Paré's treatise chapter by chapter, we find that horror is a normative reaction, a reaction engendered by a violation of a specific kind of norm. When causal knowledge, that is, knowledge of the natural causes, is produced to explain a monster, the effect of such explanation is to displace horror, to alter our experiences of the phenomenon with which we are confronted. Horror is linked to Paré's discussion of supernatural causes because the issue in these discussions is always the normative relation between the divine and human wills. A horrible prodigy is produced when the human will acts contrary to nature, contrary to the divine will, and so when this contrariness (as Aquinas makes conceptually articulate and as is reflected in Paré) involves the thwarting of a very particular kind of norm. I see no reason to doubt the accuracy of Paré's descriptions, of where and when he experienced horror, especially because this kind of description is confirmed in so many other treatises.[37] It strikes me as no odder that Paré and his contemporaries would experi-

ence horror only when confronted by a prodigy, by some especially vicious normative violation, than that the Israelites of the Old Testament would come to experience horror at the seemingly heterogeneous group of phenomena called "abominations." And the inverse relationship between horror and causal explanation is the other side of the similar relationship between wonder and causal explanation. A sense of wonder was the appropriate reaction to the production of a miracle, just as horror was the appropriate reaction to the production of a prodigy. Lorraine Daston has argued, in examining the decline of miracles and the sensibility of wonder, that "it was axiomatic in the psychology of miracles that causal knowledge drove out wonder, and in the seventeenth century the converse was also emphasized: wonder drove out causal knowledge."[38] The psychology of miracles and the psychology of prodigies were phenomenologically and analytically akin to each other.

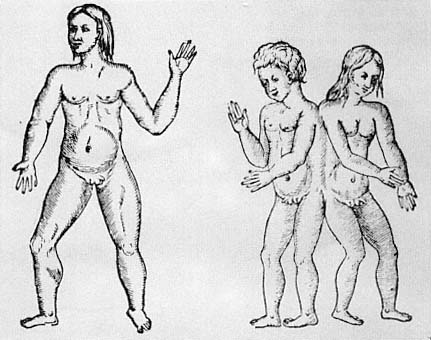

In his chapter on the mixing and mingling of seed and the hideous monsters that result from bestiality (fig. 2.9), Paré describes a man-pig, a creature born in Brussels in 1564, having a man's face, arms, and hands, and so representing humanity above the shoulders, and having the hind legs and hindquarters of a swine and the genitals of a sow (fig. 2.10). This man-pig was one of a little of six pigs and, according to Paré, "it nursed like the others and lived two days: then it was killed along with the sow on account of the horror the people had of it."[39] As one would expect from what I have argued, horror was in fact the reaction triggered by this man-pig, and it was so consuming as to push the people to kill both the sow and her monstrous offspring.

In 1699, Edward Tyson, a fellow of the Royal Society and Royal College of Physicians, communicated a report, published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, entitled "A Relation of two Monstrous Pigs, with the Resemblance of Human Faces, and two young Turkeys joined by the Breast." Tyson announces his intention at the start:

By the description of the following monsters I design to prove that the distortion of the parts of a fetus may occasion it to represent the figure of different animals, without any real coition betwixt the two species.[40]

He proceeds to describe, in much detail, a so-called man-pig, discovered at Staffordshire in 1699. His article contains no evidence of horror, disgust, dread, or any related emotion. As he continues, it becomes clear that his description of the seemingly human face of the pig is meant to show that it is the result of some depression of the pig's face, caused by a compression of the womb or by the pressure of the other pigs in the same part of the womb. No reference to bestiality is necessary to understand the production of this creature, and no horror is, or should be occasioned by it. Tyson mentions the case of a man-pig reported by Paré,

Fig. 2.9.

A monster, half man and half swine.

Fig. 2.10.

A pig, having the head, feet, and hands of a man, and the rest of a pig.

the very case I have quoted, and is content to point out some differences between Paré's case and his, for example, that his man-pig did not possess human hands. Tyson is cautious about whether recourse to bestiality is ever required to explain such monsters, but the main thrust of his article is to show that causal explanations of the kind he has produced have a much greater explanatory relevance than has often been recognized. His attitude stands at a great distance from Paré's, and it is exem-

plified by his remark, made when discussing other reported cases of monstrous pigs, "I believe either fiction, or want of observation has made more monsters than nature ever produced"[41] —sometimes almost employing the concept of monster as if monsters were thought to be creatures contrary to nature, whereas the whole point of his communication has been to show that they result from abnormal deformations due to natural causes.

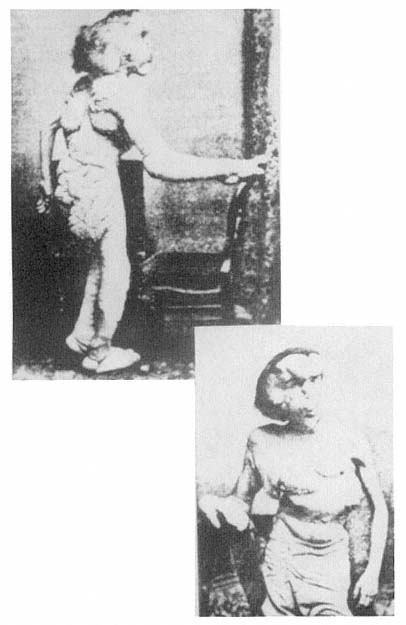

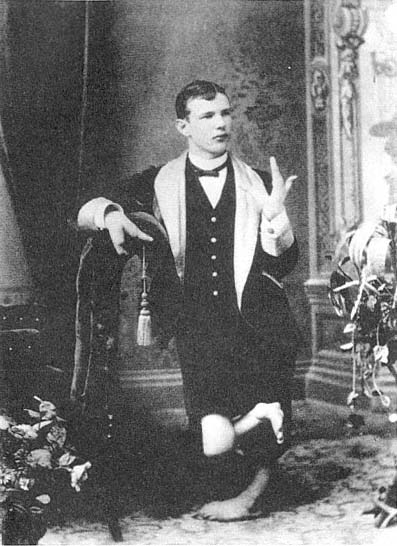

The displacement of horror as a result of causal explanation, as though knowing the cause of a monster calms the horror we might feel, can also be seen in the case of John Merrick, the so-called Elephant Man, and such displacement operates in one and the same individual, namely, Merrick's physician, Frederick Traves (figs. 2.11, 2.12). In the medical reports submitted to the Pathological Society of London, words such as "deformity," "abnormality," "remarkable," "extraordinary," and "grossly" describe Merrick's condition. The reports do not convey an experience of horror but rather an impression of how extreme Merrick's deformities are, and, because of that extremity, they indicate the immense medical interest of his condition. However, when we read Treves's memoir and he describes his and others' first encounters with the Elephant Man, the mood is completely different. Here we find words and phrases such as "repellent," "fright," "aversion," "a frightful creature that could only have been possible in a nightmare," "the most disgusting specimen of humanity that I have ever seen," "the loathing insinuation of a man being changed into an animal," and "everyone he met confronted him with a look of horror and disgust."[42] (See fig. 2.13.) It is as though we can describe Treves's emotional history by saying that when he attends to the complicated causal etiology of Merrick's condition, he can transform his own reaction from one of horror and disgust to pity and, eventually, sympathy. We often assume that the appellation "Elephant Man" derives from the fact that Merrick was covered with papillomatous growths, a derivation of this name reported in one of the medical communications. And certainly this appearance could have accounted for that title. But it is easy to forget that this is not the official reason that Merrick himself gave for his being called the Elephant Man. He reported that shortly before his birth, his mother was knocked down by a circus elephant and that this accident, with its horrifying consequences, was the source of the label, "Elephant Man." It is perfectly evident that this story conceals, and not very well, the fantasy of bestiality, and it is exactly this fantasy that is embedded in Traves's memoir when he speaks of "the loathing insinuation of a man being changed into an animal."

Although the adjective "abominable" occurs frequently in discussions of monsters and prodigies, I will not insist here on the obvious differences between this use of the term and the concept of abomination in the

Fig. 2.11.

John Merrick, 1884–85.

Old Testament. The use of "abominable" to describe prodigies remains inextricably linked to horror, as I have argued; but the doctrine of natural law, absent from the Old Testament, decisively alters one feature of the biblical conception. A study of the relevant biblical passages would show that it is primarily one uniquely specified people who, because of their special relation to God, feel horror at abominations. But in the texts I have discussed, it is rather as though the horror of sins contrary to nature, and of the products that result from them, is experienced by all human beings qua rational beings. For the use of natural reason alone is sufficient to grasp the viciousness of sins contrary to nature, and bestial-

Fig. 2.12.

John Merrick.

Fig. 2.13.

Postmortem cast of the head and neck of John Merrick.

ity, for example, is a violation of natural law, which requires no special act of divine revelation to be known but is nothing else than the rational creature's participation in God's eternal law.[43] So every human being ought to experience horror at that which he knows, as a rational being, to be contrary to nature. In this context, the doctrine of natural law helped to conceal the recognition that horror is a cultural and historical product and not demanded by reason alone, a fact that is more easily recognized in the pertinent biblical texts. Since horror came to be enmeshed in the framework of natural law and natural reason, prodigies, and the wrath of God, could be described in a way that was intended to represent the

experience of every human being, not simply the experience of a culturally specific group. Objects of horror could now directly appear to be naturally horrifying.

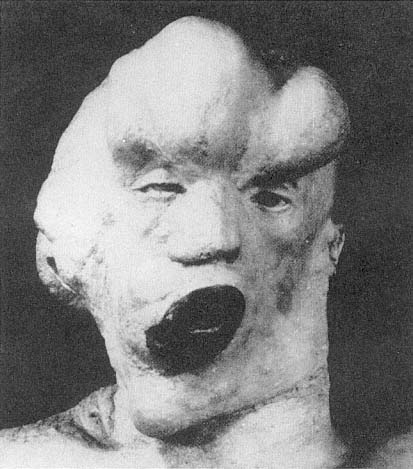

As I have already shown, bestiality, the worst of the sins contrary to nature, exhibited its viciousness in the very structure of the human body itself, in the creatures produced by the willful violation of God's natural law. But this configuration, whereby a certain kind of undermining of norms was exhibited in the effects of physical pathology, was not restricted only to this one form of lust contrary to nature. Eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century treatises on onanism reproduce this same pattern of concepts; self-abuse, another one of Aquinas's sins contrary to nature, ravages the physical structure of the body, producing, among its effects, acute stomach pains; habitual vomiting that resists all remedies during the time this vicious habit is continued; a dry cough; a hoarse, weak voice; a great loss of strength; paleness; sometimes a light but continuous yellowness; pimples, particularly on the forehead, temples, and near the nose; considerable emaciation; an astonishing sensibility to changes in the weather; an enfeeblement of sight sometimes leading to blindness; a considerable diminution of all mental faculties often culminating in insanity; and even death (fig. 2.14).[44] Indeed, this relationship between the viciousness of the sin and the pathology of the body even gave rise to a genre of autopsy report, in which the autopsy of a masturbator would reveal that the effects of this loathsome habit had penetrated within the body itself, affecting the internal organs no less than the external appearance.[45] In Tissot's L'Onanisme, Dissertation sur les maladies produites par la masturbation, we find the same kind of terminology and sensibility that accompanies Renaissance descriptions of prodigies. Tissot opens his discussion of cases, with which he has had firsthand experience, with the following preamble:

My first case presents a scene which is dreadful. I was myself frightened the first time I saw the unfortunate patient who is its subject. I then felt, more than I ever had before, the necessity of showing young people all the horrors of the abyss into which they voluntarily plunge themselves.[46]

And he invokes the idea of masturbation as contrary to nature in strategically central passages.[47]

It is often said that Tissot's treatise is the first scientific study of masturbation, and his book is engulfed by medical terminology and punctuated by attempts to give physiological explanations of the pathological effects provoked by masturbation. But it is just as evident that his book remains firmly placed within a tradition of moral theology, which begins with a conception of masturbation as an especially vicious kind of lust. It produces mental and physical disease and disorder, but even in the scien-

Fig. 2.14.

Death by masturbation.

tific treatments inaugurated by Tissot, it remains a vicious habit, not itself a disease but a moral crime against God and nature. Tissot begins his book with the claim, which he says that physicians of all ages unanimously believe, that the loss of one ounce of seminal fluid enfeebles one more than the loss of forty ounces of blood.[48] He immediately recognizes that he must then explain why the loss of a great quantity of seminal fluid by masturbation, by means contrary to nature, produces diseases so much more terrible than the loss of an equal quantity of seminal fluid by natural intercourse. When he offers an explanation, in Article II, Section 8 of his book, he attempts to frame it in terms of purely physical causes, the mechanical laws of the body and of its union with the mind. But try as he might, he cannot help but conclude this section by reintroducing the claim that masturbators "find themselves guilty of a crime for which divine justice cannot suspend punishment."[49]

Theorists of sodomy also exploited this same kind of connection between normative taint and physical deformation. The normative origin of attitudes toward sodomy is contained not only in the very word, with its reference to the episode of Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis, but also in the emergence of other words to refer to the same practices. For instance, buggery derives from the French bougrerie, a word that refers to a Manichaean sect that arose at Constantinople in the ninth century, and

which recognized a sort of pontiff who resided in Bulgaria. Thus, to be a bougre meant that one was a participant in heresy, and there is no reason to believe that this heretical sect had any special proclivity toward sodomy. However, eventually, the accusation of bougrerie came to be identified with an accusation of sodomy, and the link to heresy became submerged.[50] Moreover, in French, the phrase "change of religion" could be used to describe pederasty; to become a pederast was to change religion (changer de religion ).[51] Both sex and religion have their orthodoxies, their heresies, their apostasies—their nomrative paths and deviations.

Even when the theological underpinnings of the concept of sodomy receded into the background, its normative content and origin was always close at hand. Ambroise Tardieu, whose enormously influential Étude médico-légale sur les attentats aux moeurs was first published in 1857, devotes about one-third of this book to a discussion of pederasty and sodomy. Tardieu restricts the term "pederasty" to the love of young boys, whereas the more general term "sodomy" is reserved for "acts contrary to nature, considered in themselves, and without reference to the sex of the individuals between whom the culpable relations are established."[52] Most of the cases of sodomy Tardieu describes concern either male/male anal intercourse or male/female anal intercourse. The fact that he repeatedly characterizes these acts as contrary to nature indicates the normative tradition into which his work fits. Although Tardieu acknowledges that madness may accompany pederasty and sodomy, he wishes to make certain that these acts escape "neither the responsibility of conscience, the just severity of law, nor, above all, the contempt of decent people."[53] He is aware that the "shame and disgust"[54] that these acts inspire have often constrained the reports of observers, and his book is intended to remedy this lack, and in extraordinary detail.

Much of Tardieu's discussion of pederasty and sodomy is concerned with the physical signs that permit one to recognize that these activities have transpired, with the material traces left by these vices in the structure of the organs. Tardieu believed that an exhaustive discussion of these signs is necessary if legal medicine was going to be able to determine with assurance whether such acts contrary to nature and public morality had taken place. He describes the deformations of the anus that result from the habit of passive sodomy, a topic that had already received much discussion in the French and German medicolegal literature. But he goes on to describe the signs of active pederasty, signs left on the viril member itself, which he claims have been completely ignored in previous treatises. Changes in the dimension and form of the penis are the most reliable indications of active sodomy and pederasty. The active sodomist has a penis that is either very thin or very voluminous. The excessively voluminous penis is analogized to "the snout of certain animals,"[55] while

Tardieu describes the much more common, excessively thin penis of active sodomists in the following remarkable way:

In the case where it is small and thin, it grows considerably thinner from the base to the tip, which is very tapered, like the finger of a glove, and recalls completely the canum more .[56]

To confirm his general observations, he reports the physical conformation of the penises of many active sodomists:

Having made him completely undress, we can verify that the viril member, very long and voluminous, presents at its tip a characteristic elongation and tapering that gives to the gland the almost pointed form of the penis of a dog.[57]

Another of Tardieu's active sodomists has a penis that "simulates exactly the form of the penis of a pure-bred dog."[58] As if to confirm that sodomy is contrary to nature and God, the relevant parts of the human body are transformed by this activity so that they come to resemble the bodily parts of a dog. What could be more horrifying than the moral and physical transformation of the human into a beast, a man-dog produced no longer by bestiality but by the disgusting practice of sodomy. Long after the classical discussions of prodigies, the category of the contrary to nature continued to mark out one fundamental domain of horror.

By the late nineteenth century, the experiences provoked by so-called freak shows already contrasted with the horror of the contrary to nature. Rather than exhibiting the physical consequences of normative deviation, the freaks exhibited in sideshows and circuses were intended to amuse, entertain, and divert their audiences. In general,

the urban workers who came to stare at freaks were by and large an unsophisticated audience in search of cheap and simple entertainment. . . . In the early 1870s William Cameron Coup had introduced a two-ring concept while working with Barnum and by 1885 most shows revolved around a multiple ring system. The result was a drift toward glamour and spectacle as the basic product of the big shows. The tendency was well developed by the early nineties and brought specific changes to the exhibits. Contrasts of scale—fat ladies and living skeletons, giants and dwarfs—and exhibits involving internal contrasts—bearded ladies, hermaphroditic men and ladies toying with snakes—began to displace the more repulsive exhibits. As the shows were freighted with fewer mutilated horrors they became less emotionally loaded and less complex as experiences.[59]

It should be noted that part of the purpose of the multiple-ring circus would have been defeated by the displaying of horrors. For if having more than one ring was intended to get the spectators to look from exhibit to exhibit, to gaze periodically and repeatedly at each of the

Fig. 2.15.

Fred Wilson, the Lobster Boy.

rings, to experience the circuis in all of its diversity, then the exhibition of a horrifying object would have tended to thwart this experience. The experience of horror disposes us to fix on its object, unable to avert our gaze, fascinated as well as repulsed, blocking out virtually everything but the object before our eyes. Thus, horror is incompatible with the glamour, spectactle, and variety that is inherent in the multiple-ring circus.

Fig. 2.16.

Avery Childs, the Frog Boy.

The modern circuis has to be set up so that no single exhibit so predominated that the many rings were, in effect, reduced to one.

Even if we put aside the fact that the categories of freaks and prodigies were by no means composed of the same specimens, we can see how different this experience of freaks was by examining photograph of them. Charles Eisenmann was a Bowery photographer who took many portraits of freaks during the late nineteenth century. Some of these photographs represent characters that are half-human and half-animal and so, at least in this respect, can be thought of as successors to the medieval and Renaissance prodigies produced by bestiality. But these photographs exhibit no indication of horror. Avery Childs, the Frog Boy, is evocative and amusingly photographed but no more horrifying than a contortionist, his slippers emphasizing that he is more human than frog (fig. 2.15). Indeed, these photographs insist on the humanity of their subjects, precisely the opposite of Paré's discussions, which highlight the

Fig. 2.17.

Jo Jo, the Russian Dog Face Boy.

bestiality of prodigies. Fred Wilson, the Lobster Boy, suffers from a serious congenital deformity, but dressed in his Sunday best, with his hair neatly combed, one is drawn as much to his human face as to his supposed lobster claws (fig. 2.16). And even Jo Jo, the Russian Dog Face Boy, one of Barnum's most famous attractions, wears a fringed valour suit and sports that great symbol of Western civilization, the watch chain (fig. 2.17). Furthermore, his right hand bears a ring, and his left hand is neatly placed on his knee. And he poses with a gun, as if to suggest that he is not an animal to be hunted but can himself participate in the all too human activity of the hunt. Horror at the prodigious, amusement by the freak—the history of monsters encodes a complicated and changing history of emotion, one that helps to reveal to us the structures and limits of the human community.

Three—

The Animal Connection*

Harriet Ritvo

The dichotomy between humans and animals—or man and beast, as it used to be called—is so old and automatic that we scarcely notice it. It was enshrined near the beginning of our tradition, in the second chapter of Genesis, when God presented the animals to Adam one by one, in the vain hope that one of them would prove a fit helpmeet for him. In the end, of course, none of them would do, and God had to provide Adam with a creature more like himself.[1] At least since then, the notion that animals are radically other, on the far side of an unbridgeable chasm constructed by their lack of either reason or soul, has been a constant feature of Western theology and philosophy.[2] It has completely overshadowed the most readily available alternative, which would define human beings as one animal kind among many others.

And the advent of modern science has not made much difference. Most scientific research about animals has been founded on the assumption that they constitute a distinct class to which human beings do not belong. Thus, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century zoologists were confident that "the prerogative of reason," which animals lacked, distinguished humanity "as . . . intended for higher duties, and a more exalted destiny."[3] This confidence insulated them from the implications of such disquieting recognitions as the following, taken from an early Victorian zoological popularizer: "When we turn our attention to Mammalia . . . we find some startling us by forms and actios so much resembling our own, as to excite unpleasant comparisons."[4] Nor did Charled Darwin's formulations necessarily change things. The gap between humans and animals remained axiomatic even, or perhaps especially, in fields like comparative psychology, which focused on the kinds of intellectual and emotional qualities that were also assumed to distinguish us as a species.

George Romanes, a pioneer in such research and the friend and protégé of Darwin, tried to quantify this discontinuity in a book entitled Mental Evolution in Animals, published in 1883. It included a graphic scale of emotional and intellectual development, presented as a ladder with fifty steps. Civilized human adults, capable of "reflection and selfconscious thought," were at the top. Then there was a large hiatus. The highest animals were anthropoid apes and dogs, which Romanes considered capable of "indefinite morality" as well as shame, remorse, deceitfulness, and a sense of the ludicrous. They occupied step 28, along with human infants of fifteen months. Close behind them, on step 25, were birds, which could recognize pictures, understand word, and feel terror; and they were followed on step 24 by bees and ants, which could communicate ideas and feel sympathy.[5] The details of this schematization sound quaint now, but its underlying taxonomy, which defines humans and animals as separate and equivalent categories on the basis of their intellectual, spiritual, and emotional capacities, continued to determine the course of research on animal behavior for the succeeding century. As Donald Griffin, a contemporary critic of this taxonomy, has pointed out. "Throughout our educational system students are taught that it is unscientific to ask what an animal thinks or feels . . . [and] field naturalists are reluctant to report or analyze observations of animal behavior that suggest conscious awareness . . . lest they be judged uncritical, or even ostracized from the scientific community."[6]

Although the dichotomy between humans and animals is an intellectual construction that begs a very important question, we are not apt to see it in that light unless it is challenged. And serious challenges have proved difficult to mount. Those who have based their thinking on the uniqueness of our species (i.e., its uniqueness in a different sense than that in which every species is unique) have often resisted even the attempt to make the dichotomy controversial. The scientific consensus cited by Griffin exemplifies entrenched institutional reluctance to acknowledge that an alternative taxonomy might be possible. An analogous refusal by philosopher Robert Nozick structured his review, which appeared several years ago in the New York Times Book Review, of Tom Regan's The Case for Animal Rights . Instead of grappling seriously with Regan's carefully worked out and elaborately researched argument, Nozick simply dismissed it by asserting that animals are not human and therefore cannot possibly have any rights. That is, he claimed that Regan had made a crippling category mistake by failing to recognize the insuperable barrier that separated humans from all other creatures and that it was therefore not necessary to think seriously about anything else that he said.[7] Such views are not confined to scholars and scientists; so, despite its evasiveness, Nozick's stratagem is unlikely to have bothered

many of his readers. Recent research suggests that most ordinary Americans explicitly endorse the dichotomy that Nozick postulates, whatever else they may think or feel about animals, for example, whether or not they like them, or whether they wish to protect them or to exploit them.[8]

But this repeatedly avowd taxonomy is not the whole story, either about the relationship of human beings to other species or about the way that people have perceived and interpreted that relationship. There are other indexes of belief and understanding than explicit declarations. In the case of other animals, and especially the mammalian species that human beings resemble most closely, the explicit denial of continuity may paradoxically have freed people to articulate, in a veiled and unselfconscious way, their competing sense of similarity and connection. A lot of evidence suggests that when people are not trying to deny that humans and animals belong to the same moral and intellectual continuum, they automatically assume that they do. Discourses that seem to refer exclusively to animals are frequently shaped by cultural constructions clearly derived from human society, even in the scientific and technological fields where it might seem that such constructions would be counterproductive, out of place, and easy to identify and discard. The consequences of this unacknowledged connection have often been enormous, even in the behavioral sciences most strongly committed to reinforcing the dichotomy between humans and animals. Thus, it is no accident that the baboon studies published by S. L. Washburn and Irven DeVore in the 1950s and 1960s stressed the importance of male dominance hierarchies. Analogously, the research undertaken by the increasing number of female primatologists in the past two decades has emphasized the extent to which female primates aggressively manage their own reproductive careers, radically revising earlier characterizations of them as sexually passive and even "coy."[9]

thus animal-related discourse has often functioned as an extended, if unacknowledged metonymy, offering participants a concealed forum for the expression of opinions and worries imported from the human cultural arena. Indeed, much of what people—experts of one sort or another—have said about animals can only be explained in this context. Thus, the foregoing examples from the recent history of primatology suggest how social or political ideology can determine the research agenda of scientists. But these examples may seem too easy. After all, despite the explicit professional commitment of primatologists not to anthropomorphize the animals they study, those creatures are of special interest exactly because of their closeness to humankind. They are obvious targets for projection, as are the extinct pongide and hominids whose fossil remains are interpreted by students of human origins.[10]

It is, however, possible to find evidence that the same intellectual and

cultural preconceptions shape discourses that, on the face of it, look much less promising. One such discourse informs the literature of animal breeding that emerged in late eighteenth-century Britain and developed and flourished throughout the next century. The ostensible subjects of this discourse—horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, dogs, and cats—share far fewer characteristics with human beings than do apes, monkeys, and australopithecines; its participants were concerned with practical results, rather than with anything so abstract and potentially tendentious as the increase of knowledge or the development of theory.