Preferred Citation: de Gobineau, Arthur Joseph. Mademoiselle Irnois and Other Stories. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1987 1988. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2w1004x8/

| "Mademoiselle Irnois" and Other StoriesArthur de GobineauUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1988 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: de Gobineau, Arthur Joseph. Mademoiselle Irnois and Other Stories. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1987 1988. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2w1004x8/

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to the staff of the Millikan Library of the California Institute of Technology, in particular Janet Jenks, Judith Nollar, and Ruben Ybarra for their help with references; to the staff of the Cabinet des Estampes of the Bibliothèque Nationale, especially Jacqueline Martinet. David Elliot helped us with military and Lance Davis with economic history. For reading and responding to various sections and stages of our work, we want to thank Jean Gaulmier, Jean Boissel, Pierre-Louis Rey (who also provided us the photograph of Gobineau), Virgil Burnett, Jerome McGann, Oscar Mandel, Eleanor Searle, and John Sutherland. We are both endebted and grateful to our colleague George Pigman III, who has patiently and generously educated us in word processing, formatting, and typesetting (and when education failed, took over); to John R. Miles, who encouraged us early in the game, when it most counted; to our editor Scott Mahler, a loyal champion of our manuscript; to David Grether, chairman of the Humanities and Social Sciences Division of the California Institute of Techology, for a travel grant which permitted iconographic research and for other financial assistance; and finally to each other: Amant alterna Camenae .

ANNETTE AND DAVID SMITH

Foreword

Introducing at a century's distance a fiction writer who was also a historian, a philosopher, and a self-taught scientist requires a large and complex web of information. Rather than annotate the introduction and translations excessively, we would like to acknowledge here the sources to which many of our pages refer whether annotated or not. The three volumes of the Pléiade edition of Gobineau's Oeuvres , edited by Jean Gaulmier with the collaboration of Jean Boissel (Vol. I), of Pierre Lésétieux and Vincent Monteuil (Vol. II), and of Jean Boissel and Marie-Louise Concasty (Vol. III), amount to a condensed research library. The three volumes represent the culmination of several decades of studies centered (from 1966 to 1978) around the Etudes gobiniennes . Boissel's Gobineau, L'Orient et l'Iran (Paris: Klincksieck, 1973) [cited as L'Orient et l'Iran ] and Gobineau (Paris: Hachette, 1981) and Pierre-Louis Rey's Univers romanesque de Gobineau (Paris: Gallimard, 1981) [cited as Univers romanesque ] provide comprehensive treatments of Gobineau's relationship with the Middle East, his life and his aesthetics, respectively. Finally, some of the ideas in the first two sections of the introduction are borrowed from a study by Annette Smith, Gobineau et l'histoire naturelle (Paris/Geneva: Droz, 1984). Still, not all has been said elsewhere, and it is our hope that this hearty sampling of Gobineau's short stories will give English-speaking readers an appetite for the rest of the fare.

The texts on which our translations are based are those of the Pléiade edition, in which typographical errors as well as numerous small errors inadvertently introduced by the author have been corrected by the editors. Still, there remain many baffling lines and redundancies that stem from Gobineau's generally spontaneous and emotional, rather than logical, style. His punctuation as well was personal, at times erratic. For the most part, these flaws and eccentricities have been reproduced in the translation as part of his écriture ; only those that would have interfered with clarity have been altered.

We have also observed French conventions regarding the punctuation of dialogue (though using American quotation marks), in part because they better render Gobineau's mode of handling it and in part because they help retain the flavor of the French text, albeit translated. To a similar though temporal end, we have occasionally and unobtrusively, we hope, capitalized somewhat more in accordance with nineteenth-century practice than that of our own time.

With regard to rendering Gobineau's approximations of Arabic, Turkish, and Persian words and place-names, we looked for English transliterations from the period or as close to it as possible. With this in mind we used the following sources in this order of priority: J. J. Morier, The Adventures of Hajji Baba of Ispahan (London, 1851) and A Journey through Persia, Armenia and Asia Minor . . . (London, 1812); J. P. Ferrier, Caravan Journeys and Wanderings in Persia, Afghanistan, Turkestan . . . (London, 1856) and History of the Afghans (London, 1859); A. W. Kinglake, Eothen (London, 1893); E. G. Browne, A Year amongst the Persians . . . (London, 1893); and S. G. Wilson, Persian Life and Customs . . . (New York, 1899). We only exceptionally borrowed from The Travels of Sir John Chardin into Persia and the East Indies (1691) as it is of another era. We favored the first four works because Gobineau knew Morier's and

Ferrier's writing. These authors were rarely consistent vis-à-vis one another and not always consistent within their own works, and concessions had to be made to common sense and euphony. Finally, Webster's International Dictionary proved helpful when all else failed.

As a rule we have refrained from annotating words that are sufficiently explained in the text by the author, but for convenience we have annotated foreign words and those that would require the average reader to seek help in a dictionary or an encyclopedia.

While a general background for Gobineau seemed desirable before approaching the texts, information relevant to each one of the stories as well as our own critical notes on the stories are presented at the end of the volume. Thus, general readers eager to attack the fiction will not be delayed by the scholarly apparatus and need not go further than the stories themselves. Scholars and students of literature will, it is hoped, find the afterword useful. All translations are our own unless specified otherwise.

For a complete Gobineau bibliography, see any of the works mentioned at the beginning of this foreword. In addition to the Pléiade edition of the Oeuvres , we list below all editions and collections of Gobineau's works cited in the notes and, where appropriate, the abbreviations used.

Bibliothèque Nationale et Universitaire de Strasbourg (Fonds Gobineau). [BNUS]

Correspondance entre le Comte de Gobineau et le Comte de Prokesch-Osten (1854–1876). Paris: Plon, 1933. [Corr. Prokesch-Osten ]

Correspondance Tocqueville-Gobineau. In A. de Tocqueville, Oeuvres complètes , Vol. IX. Paris: Gallimard, 1959. [Corr. Tocqueville ]

Les Dépêches diplomatiques du Comte de Gobineau en Perse , edited by A. Doris Hytier. Geneva: Droz, 1959. [Dépêches diplomatiques ]

Deux études sur la Grèce moderne. Paris: Plon-Nourrit, 1905.

Dom Pedro e o Conde de Gobineau , edited by G. Raeders. Sao Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional, 1938. [Corr. Pedro ]

Ecrits de Perse: Treize lettres à sa soeur , edited by A. B. Duff. Mercure de France (Nov. 1957): 385–415.

Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines , edited by J. Boissel. In Oeuvres , Vol. I, pp. 1174. [Essai ].

Etudes critiques (1842–1847) , edited by R. Béziau. Paris: Klincksieck, 1984.

Etudes gobiniennes , Vols. I–IX, edited by J. Gaulmier. Paris: Klincksieck, 1966–1978.

Histoire d'Ottar Jarl, pirate norvégien. . . .Paris: Didier et Cie, 1879. [Ottar Jarl ]

Lettres à deux Athéniennes , edited by N. Mela. Athens: Lib. Kauffmann, 1936.

Lettres brésiliennes , edited by M. L. Concasty. Paris: Editions du Delta, 1969.

Mademoiselle Irnois, Adélaïde et autres nouvelles , edited by P.-L. Rey. Paris: Gallimard, 1985 [Mademoiselle Irnois ].

Nouvelles asiatiques , edited by J. Boissel. In Oeuvres , Vol. III, pp. 305–573.

Les Pléiades , edited by J. Gaulmier. In Oeuvres , Vol. III, pp. 929–1168.

Oeuvres. 3 vols. Paris: Gallimard, 1983–1987. [Pl. I, Pl. II, Pl. III]

Poemi inediti di Arthur de Gobineau , edited by P. Berselli Ambri. Florence: L. Olshki, 1965. [Poemi inediti ]

Les Religions et les philosophies dans l'Asie Centrale , edited by J. Gaulmier and V. Monteuil. In Oeuvres , Vol. II, pp. 403–809. [Religions et philosophies ]

Trois ans en Asie , edited by J. Gaulmier and V. Monteuil. In Oeuvres , Vol. II, pp. 27–401.

Voyage à Terre-Neuve . Paris: Hachette, 1861.

Introduction

In the realm of French literature, one of the surest signs of an author's consecration is inclusion in the definitive, critical Bibliothèque de la Pléiade published by Gallimard. The works of Arthur de Gobineau finally received such recognition in 1983, missing the centennial of his death by one year. Gobineau would, however, have been satisfied. "Time is on my side," he wrote in 1869.[1] He also wrote, "My contemporaries will only appreciate me one hundred years after my death,"[2] which, perhaps, offers evidence of clairvoyance, if not logic. But then Logic and Luck were not among those presiding over his birth. It would be difficult to name a nineteenth-century writer more at odds with his era.

The simplest way to characterize Gobineau is by the prefix anti. He was antirepublican, anticolonialist, antiprogressive, and antievolutionist in the century of democratization, imperialist expansion, technical progress, and Darwinism. As a student, he was judged impertinent and expelled from school. As a writer, he offended even some of his strongest supporters (Tocqueville, for one) with the somber anti-Christian determinism of Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines , irked such veteran orientalists as Botta, Pott, and Mohl with his eccentric explanation of the cuneiforms, and ranted in vain against evolutionists as entrenched as Lyell, Oppert, and even Darwin. But he felt an equal contempt for the "so outrageously ignorant and inept" good Catholics

in the opposite camp.[3] As a diplomat in Greece, he antagonized his English and Russian counterparts as well as the Greek Nationalists. And he periodically infuriated his administrative superiors with his constant complaints, leaving a voluminous record of his squabbles with them in a thick (still unpublished) dossier monomaniacally labeled "Various Knaveries." Yet, this rebel sought admission to the Legion of Honor and usurped the title of count, courted, however awkwardly, seats in two academies, and solicited an audience with Napoleon III, "that Bonaparte" whom he despised almost as much as the "Rrrrépubbblique."[4] His personal life ended in vociferous strife with his wife and two daughters and led to a testament worthy of the Divine Marquis: "I hereby leave and bequeath what Madame de Gobineau my wife has not stolen or spent from my estate to Baroness de Guldencrone, born Diane de Gobineau . . . and do so only because the law requires it."[5]

Should we see him, as one of his most sympathetic critics does, as "a torn and aggressive being, tentative and proud . .{nb. dreaming of what he is not and rejecting what he is"[6] or, more prosaically, as a neurotic? Neither view is an inducement to read his works or to learn more about him. But we can also see in him a loving newlywed; an attentive, if demanding, father; a fiercely loyal and sometimes chivalrous friend. He was cultivated by many eminent personalities of his time and, because he was a brilliant conversationalist, was lionized by many hostesses. Although reduced to a roving bachelorhood during the last twenty years of his life, he invariably found, wherever he was stationed, the love of women who were always beautiful and often distinguished. Perhaps the secret of his charisma lay in his indomitable energy. The young writer's naive mottoes (Réussir ou mourir or Malgré tout ), the adult's passion for daring voyages, the older man's willing plunge into a second career, all show the same lust for life. It takes unusual faith in oneself, in art, and in the

world to take up the sculptor's chisel as a serious commercial venture after twenty-eight years of civil service. Gobineau worked at his sculpture with the same magnitude of conception demonstrated in his most ambitious poetic works. Unlike his fiction, his sculpture, unfortunately, turned out to be as mediocre as his poetry. Still, the vision of a penniless, aged, feverish, and half-blind Gobineau stubbornly carving away in his barren Rome studio (which he once considered sharing with an ill-treated donkey) offers a clue to the question of why, after fascinating his contemporaries, he has been hailed by ours as one of the real tempéraments in French literature. Whether he is also "the most underrated writer in the nineteenth century"[7] is for his readers to decide.

"We Were, in Short, the Uprooted"[en8]"We Were, in Short, the Uprooted"[8]

In another display of singular logic, Gobineau wrote of his birth in 1816 in Ville-d'Avray, "I was born on a Fourteenth of July . . . which proves that opposites often come together."[9] What it proved is unclear; but what Gobineau meant to indicate was the irony of this child of a Legitimist family, later a man haunted by a nostalgia for the old monarchic order and boasting of a Viking Jarl as his ancestor, having been born on Bastille Day. His father, Louis, an officer from an ancient and distinguished Bordeaux family, was indeeed faithful enough to the Bourbon kings that he went to jail on this account in 1813 and was later (in 1831) ordered to retire. Thus, the family settled into the relative poverty that would plague Gobineau all his life, even though he was at heart disdainful of material possessions. While he maintained a satisfactory relationship with his respectable but mediocre father, it was his mother who really shaped his destiny. Anne-Louise Madeleine de Gercy brought to the marriage the double enigma of a father who might have been

one of Louis XV's bastards and of a Creole mother from Santo Domingo. While Creoles are, of course, defined as of pure white blood, by a curious metonymy, they represented for Gobineau (who married one himself) the closest thing to mulatto women, in whom he found "an often powerful charm."[10] Madeleine de Gobineau was restless and bored by provincial life and had literary ambitions, which eventually resulted in two obscure publications. The story of her life is not unlike that of a less worthy "Muse du Département," that daring Balzac heroine. But what makes a good feuilleton rarely makes a good family.

After the birth of a second child, Caroline (who was always to remain Gobineau's confidante), Madame de Gobineau had another daughter by her children's young preceptor, Charles de La Coindière. In 1827 (Gobineau was then eleven) she and her lover left the conjugal home, taking the three children along on a life of wandering and less than straight business. In 1830, charged with swindling, she fled to Basel and then to Bienne, also in Switzerland, where Gobineau attended the local gymnasium for approximately eighteen months. Madame de Gobineau thereby fulfilled the old truth that no parental curse or beneficence is unmitigated. For while she created in the young Gobineau an immense insecurity and anxiety about his origins (one she would later increase by circulating rumors that he was a foundling), she was also responsible for giving him a solidly Germanic and Germanophile education. The gymnasium masters introduced him to eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century German idealism and its two-pronged currents: organicism and orientalism. The former promoted a biological model for all aspects of human endeavor, particularly in the social sciences; the latter, a rediscovery of the Orient as the cradle of Western civilization. Gobineau's lifelong tropisms—his organic view of history and his obsession with origins (of mankind, of cultures, of writing, of Persia, and eventually

of his own family)—were activated by the curriculum of the Bienne gymnasium and reinforced, in the second case, by the basic and private wound of a displaced and ill-loved child.

In 1834, the two older children were called back to France by their father, then living in Lorient. Instead of pursuing mathematics, which would have opened to him the doors of Saint-Cyr, Gobineau embarked on a program of general studies, of which the classics, folklore and (even this early) oriental subjects and languages comprised a sizable part. In October 1835, having failed to gain entrance to the military academy, he left for Paris with fifty francs in his pocket. His Parisian uncle, Thibault-Joseph, an aging lecher and the supposed "rich uncle," never became the gold mine anticipated by the family. Gobineau rented a garret and painfully survived with menial jobs. This harsh initiation into the "hell" of Paris triggered his lasting hatred of the metropolis and his eventual self-imposed expatriation.

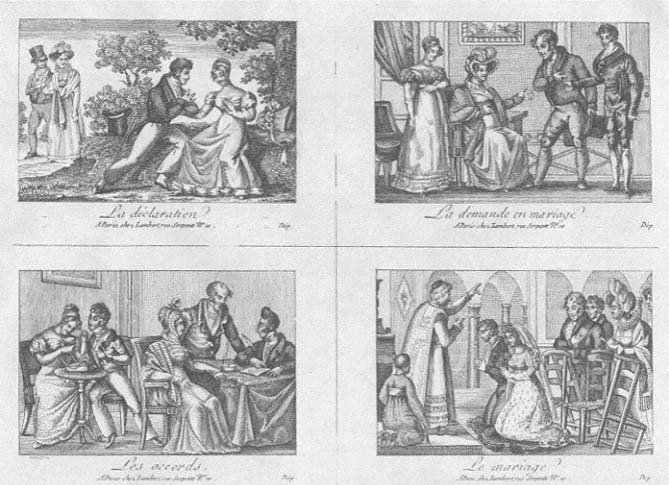

He had arrived with letters of introduction to some of the eminent men and fashionable salons of the time. The lively correspondence with his family—his sister in particular—constitutes a humorous documentation of the life of an impecunious twenty-year-old would-be dandy and already committed intellectual. Under the wings of such established scholars as Mohl, Baron Eckstein, Quatremère, Sainte-Beuve, acquainted with Ballanche, Lamartine, de Maistre, Lacordaire, Talleyrand, Tocqueville, and even Alexander von Humboldt, the great anthropologist and pioneering ecologist, Gobineau served his apprenticeship as a mediocre poet, passable orientalist, and gifted journalist. Between 1840 and 1848, he published several feuilletons, including "Mademoiselle Irnois," and wrote one tragedy. With a group of selected friends (the "Scelti") he founded the soon-aborted Revue de l'orient and then, in 1848, the more serious Revue provinciale , dedicated to the administrative decentralization of France. Sometime in 1844, Gobineau, who in the

first years of his Parisian life had had his heart broken by a provincial girlfriend, met Clémence Monnerot, and in 1846 he married her. Whether coincidence or the result of Gobineau's personal bent, she, like Gobineau's maternal grandmother, was a Creole, and, like his mother (who by then had seen the inside of several prisons), seems to have been a willful woman. Beautiful enough to have served as a model for Chassériau, distinguished in manners and with a flair for elegance, Clémence nevertheless repeated the pattern set by Gobineau's family: she eventually left her husband. However, in 1849, the turning point in his career, their marriage was quiet and happy. The couple became the parents of a daughter, Diane, and only the lack of money prevented perfect happiness. But that same year, their financial situation improved. Tocqueville, who had been one of Gobineau's mentors since 1843, became minister of foreign affairs and took his protégé as his chef de cabinet , then secured his appointment as first secretary of the French Legation in Berne.

It was thus that Gobineau's thirty-year career as a maverick diplomat began. He was not a success. Although his journalistic training had given him a fine intuition about foreign affairs, he was cantankerous, frank, stubborn, proud, and poor—five reasons for his superiors, many of whom were run-of-the-mill bureaucrats, to dislike him. His posts and missions took him all over the world, from Switzerland to Greece, from Germany to Newfoundland, and from Brazil to Sweden. By far the most important assignment for Gobineau's intellectual maturation was his being posted to the Middle East, which he welcomed as "the real thing" after his merely bookish (and perhaps superficial) knowledge of the Orient.

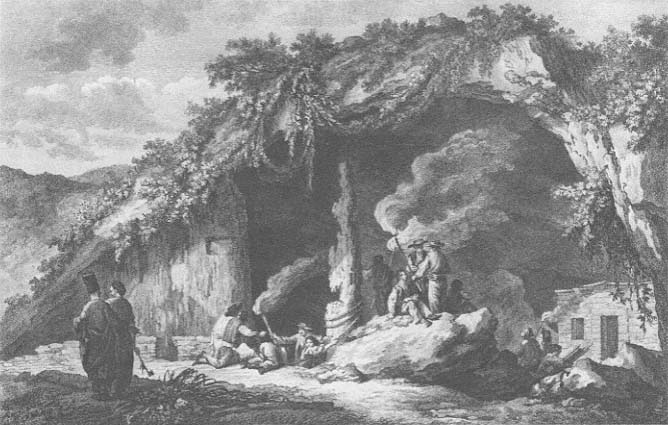

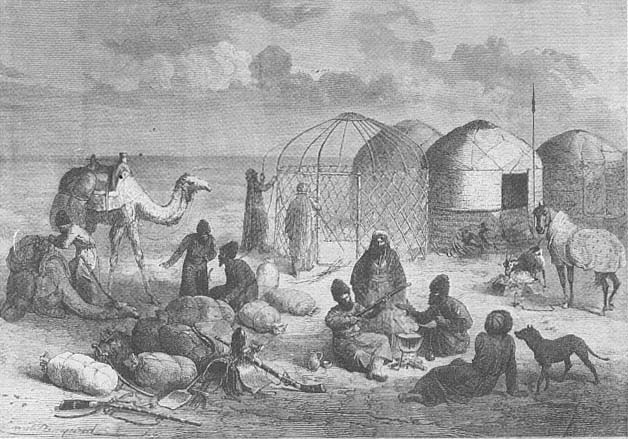

He went twice to Persia. The first time, from May 1855 to January 1858, he was chargé de mission , then head of the French Legation. During this period, he traveled in a caravan from Boûchir to Teheran, camping in the midst

of bedouins. The impression made on the neophyte Gobineau by this rough but relatively genuine way of apprehending Persia and by the unforgettable visions of Persepolis and Ispahan would color forever his responses to the Middle East. Teheran, where he and his family enjoyed the novelty of being western "potentates," was, at least at first, more to the taste of Clémence. But soon, cholera, administrative harassment, the corruption of French adventurers in Persia, diplomatic complications resulting from the aftermath of the Crimean War and from the war between Persia and Afghanistan, and Clémence's increasing loneliness disenchanted them with the diplomatic profession. Nothing, however, succeeded in causing Gobineau to be disenchanted with Persia itself. After eighteen months, Clémence insisted on returning to France with Diane; Gobineau accompanied them to the Russian frontier. At this time cholera was taking its toll everywhere, and Gobineau almost lost his own daughter, if not to cholera, to an exotic fever. Clémence, exhausted and pregnant, and Diane, barely recovered, dragged themselves through the Caucasus to the Black Sea where, thanks to the intervention of a close friend, the Austrian statesman Prokesch-Osten, they were able to regain Constantinople on an English frigate, though not without encountering a storm so terrible that the tiller broke and the passengers had to be lashed to their bunks. It is not surprising that Clémence was hardly on solid land when she bought (with the money left by Thibault-Joseph, who had finally condescended to die) the small castle of Trye near Beauvais and that she was, thereafter, less willing to accompany her husband on diplomatic missions. Persia, which had fulfilled Gobineau's dreams to the point that, as he wrote later, he would mourn it the rest of his life,[11] had indeed been a double-edged bounty.

Gobineau himself returned to France. By then, he had published his extravagant Lecture des textes cunéiformes and was working on Trois ans en Asie and L'Histoire des Perses .

In 1859, he turned down an appointment in China and accepted a diplomatic mission to Newfoundland, a seven-month trip to which we owe the story, "The Caribou Hunt." In 1862 and 1863, Gobineau, now plenipotentiary, returned alone to Persia via Constantinople and the Caucasus. This time he stayed mostly in Teheran, which allowed him to expand his knowledge of Persian and Arabic languages and literatures. Under the guidance of rabbis and mullahs, he led the life of "a happy alchemist," wallowing in rare manuscripts and old books and attempting to become "more Persian than the Persians."[12] He finished another work on cuneiforms as well as Les Religions et les philosophies dans l'Asie Centrale . But partly under pressure from his wife, who had been lobbying for his transfer and who had not yet entirely given up her conjugal prerogatives, Gobineau had himself put on leave and returned home. Clémence succeeded almost too well. There were rumors of an appointment in Washington. Nothing could have more appalled Gobineau, who saw the United States as the cauldron of all evils: not only did the Americans treat Indians and blacks cruelly, disowning in private their public ideals, but, even worse, theirs was the prototype of a democratic, technological, and uniform mass culture. Fortunately, he was appointed to Greece. Gobineau, Clémence, and their (by then) two daughters arrived in Athens in November 1865.

If Persia had been an intellectual catalyst for Gobineau, Greece was the station where he achieved the greatest personal happiness. This time, Clémence condescended to go along; the appointment promised to be glamorous. Her elegance and the beauty of her two daughters thrilled the court of nineteen-year-old King George I. The family's status reached its apex in April 1866 when, with pomp and circumstance, Diane married one of the king's aides-de-camp, the Danish Baron de Guldencrone, on a French frigate in Piraeus harbor. Acquiring a real Viking as a son-in-law fit perfectly

Gobineau's Aryan myth. Gobineau now turned to a new cycle of literary production, partly under the influence of Zoé and Marie Dragoumis, two sisters of an enlightened Athens family, one of whom, Zoé, he secretly loved for many years. Excursions to Corfu, Naxos and Santorin, with their many remains of medieval French occupation, motivated him to see to the publication of his historical novel, L'Abbaye de Typhaines . He wrote "The Crimson Handkerchief" and was already conceiving the fine "Akrivie Phrangopoulo" and a collection of poems, L'Aphroessa , which was no less mediocre than his earlier ones.

Greece could have been interesting professionally. Still trying its wings as a sovereign state, it depended on the protection of England, France, and Russia. Gobineau was not, unfortunately, the supple mediator that the situation required. Moreover, he was exasperated by the Greek Nationalists' push for expansion, which he considered immature (he noted in "Akrivie Phrangopoulo" that Turkish rule in the Cyclades had at least the advantage of having maintained a very low profile). His years in Persia had made him a supporter of the crescent rather than the cross. Perhaps the most embarrassing and painful moment in his career came when he had his compatriot, Gustave Flourens (the son of physiologist Pierre Flourens, whom he admired very much), arrested and deported for agitating in favor of the Cretan insurrection. But what good could be expected from a country that, although it boasted of descending from the original Hellenes, offered one of the worst examples of racial mixing?

Alas, the Greek Eden turned out to be only an oasis. Gobineau was appointed plenipotentiary to Rio de Janeiro and took up his post in March 1869, without Clémence. The single bonus of his new position was an active intellectual friendship with Emperor Dom Pedro II. Although he continued to kindle the flame in his letters to the Greek sisters, he was not long in finding another muse, a Brazilian Bovary,

Aurea Posno, with whom he would for several years exchange curiously ambiguous letters. But the miasma of Brazil did not agree with him. In his boredom, his imagination flew back to sunny Greece or to other times. He wrote two epics in verse, Beowulf and the first version of Amadis , and two of his best stories, "Akrivie Phrangopoulo" and "Adélaïde."

In 1870, having contracted swamp fever, Gobineau was granted a medical leave. He returned to his beloved Trye, where he had been elected mayor. It could not have been a worse time to exercise his stewardship. Because of his education and his many friends amongst the German intelligentsia, he did not believe that Germany would ally itself with Prussia or that the Prussian soldiers could become barbarous ruffians. The Franco-Prussian War proved him wrong on both counts. However, Gobineau performed his duty as first magistrate impeccably, organizing the defense of the canton, staying in the village while the population fled, and negotiating with the Prussians in place of the prefect, who also had fled. In 1871, he mediated between the Thiers government and the occupiers, considerably reducing the war levy for the department of the Oise. But in the opinion of his constituents, none of this made up for the fact that he spoke German fluently and had a polite relationship with the German officers billeted in his chateau or that his son-in-law was a blond, blue-eyed foreigner. During that year, Gobineau, whose material circumstances bordered on misery, watched the struggle between the Commune and the Versailles government with relatively less contempt and more sympathy for the popular rebellion than for the Versaillais. But in the midst of the turmoil, his major preoccupation remained the writing of his longest and most ambitious novel, Les Pléiades .

Fortunately for his purse, for he was by then reduced to expedients, Gobineau was appointed plenipotentiary to Stockholm in 1872. His correspondence from Sweden shows, at first, his delight at being in the only part of the world that,

according to him, retained traces of the great Aryan race. His literary production was at full momentum: he started on Nouvelles asiatiques and La Renaissance , published Souvenirs de voyage and finished Les Pléiades . Perhaps Gobineau felt relieved that Clémence did not endure Stockholm for more than six months. After her departure, he channeled his full emotional and intellectual energy into a passionate relationship with Mathilde de La Tour, an Italian diplomat's wife, who became his constant love, companion, and protector throughout his last years. Whether it was this liaison or a series of petty financial quarrels with his wife and daughters that precipitated it, the rupture with his family was permanent by 1876; and Trye, the only fixed residence Gobineau had had in his wandering existence, was sacrificed to this intensive war.

In January 1877, Minister of Foreign Affairs Descazes, feeling (with good reason) that Gobineau, who had been traveling with Dom Pedro for four months, had become a plenipotentiary in absentia, summarily retired him. For the next six years, Gobineau resumed his nomadic life, this time between Italy, where Madame de La Tour resided; Chaméane, her castle in the center of France; Solesme, the Benedictine abbey which his sister had entered in 1868; Paris; and, occasionally, Bayreuth, as the guest of Wagner, whom he had met in Berlin and Venice. (Posterity would later brand mere literary exchanges regarding Amadis and Nouvelles asiatiques as the conspiracy of the prophet and the cantor of the master race.) The second version of Amadis , written during the period 1877 to 1879, was Gobineau's swan song. In these years, he devoted himself almost entirely to his sculptures and to complicated schemes through which he hoped to sell them. His health, which was seriously impaired by the Brazilian fevers, declined, and he began to lose his sight. He bore his poverty and physical ailments with an elegant stoicism, finding solace in Madame de La Tour's tenderness, the loyalty

of his old servant, Honoré, and the affection of his two dogs. On October 13, 1882, on his way from Chaméane to Pisa, where his friend San Vitale awaited him, he felt exhausted and took refuge in a hotel in Turin. The next day, in the carriage taking him back to the train station, he suffered a massive stroke. He died at around midnight, alone in a simple hotel room in a strange city. It was the last caravansary in a nomadic life; he would have preferred a tent and a camel train.

History, Natural and Otherwise

Gobineau's literary works cannot be presented without a discussion of his Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines as it is the cornerstone of his worldview. It is also the basis for Gobineau's reputation as apologist for the master race and instigator of the Holocaust. In fact, this reputation is undeserved, for to have had the impact on modern history that some claim, the Essai would have had to have been read widely, especially in Germany. We can now make a reasonable estimate of its readership in the years following publication: four hundred readers in France, perhaps one hundred fifty in Germany.[13] And in both countries, it received very few reviews; the most extensive, by the linguist, Pott, was not favorable. One of the two direct forefathers of National Socialism, Houston S. Chamberlain, Wagner's son-in-law, belittled Gobineau, calling him a paranoid, an unrealistic dreamer not interested in building a Brave New World; the other, Alfred Rosenberg, never mentioned him.

It is true that after 1890 awkward attempts by the Gobineau Vereinigung (a group of Gobinolators headed by Ludwig Schemann) to salvage his reputation in Germany succeeded in making La Renaissance and Nouvelles asiatiques better known. And when Wilhelm II mounted the throne in

1890, German neo-Nationalists and expansionists exhumed the Essai from thirty-five years of obscurity and claimed to find in it a theoretical justification for their will to power. But Gobineau was dead by then and, alas, could not protest the astonishing twists given his ideas. It is also true that around the turn of the century, when anti-Semitism grew in Western Europe, it found an excuse in Gobineau's sentimental and mythical vision of the original Aryans, even though that vision had as many practical implications for its author as the Golden Age might have had for Ovid. Indeed, Gobineau twice referred to his projection of the distant future as a "divination."[14]

The Essai irked enough of Gobineau's contemporaries to block his election to the Académie française, but for reasons arising from concerns that are quite different. Tocqueville, for instance, disapproved of its anti-Christian determinism, which he perceived as a sort of Jansenism in the guise of science; Quatrefages, an anthropologist, found Gobineau's argument regarding miscegenation scientifically unconvincing; and Renan abstained from reviewing the book, undoubtedly because he was about to pilfer it in his Histoire générale et système comparé des langues sémitiques . Gobineau never thought of the Jews as a race , since the Semites were but one branch of the original white race and the Jews but one of the Semitic groups. In contrast, Renan wrote that "the Semitic race . . . truly represents an inferior combination in human nature."[15] Why is it, then, that "Renanism" did not supersede "Gobinism" as a synonym of anathema in the French language? And if the standard should be biological determinism, why not talk of "Tainism" or "Zolaism," among others? Moreover, at the time the Essai appeared, Germanophile attitudes were not extraordinary in France. Around 1850, the hereditary enemy was still England; the tradition of revenge against the Huns did not enter French life prior to the 1870 defeat by Prussia. Gobineau grew up

and wrote in a literary world in which Germany had been an ally and, occasionally, a figurehead.

If one actually reads the Essai (its length makes it a chore), it becomes clear that Gobineau would not plead guilty to the three counts he has been charged with. First, the Essai could not possibly confer on the Aryan race a mandate to rule the world, since Gobineau considered the race extinguished by centuries of miscegenation and relegated its pure state to a legendary prehistoric time.[16] He conceded that a few isolated remnants might still survive in Norway, Sweden, and Great Britain, but all other modern nations had long since diluted their pure white blood with black or yellow blood. The Latin peoples were especially tainted, as were the French and even the Germans , those "hybrids" (métis ). Second, expansionism (such as the Third Reich later sought) contained the seeds of its own destruction: no race could conquer others and remain pure, no state could expand and remain stable and free . Disequilibrium was built into growth; aggressive civilizations escaped the Charybdis of instability only to crash into the Scylla of despotism. The Essai , then, could never have sponsored national socialism since the core of its political argument (if there was one at all) goes against all forms of centralized government, from the early Hamite despots to the modern American megastate via the Greek city and the Roman Empire. Only local, self-contained, and organic modes of government, such as the ancient Aryan Odel, could achieve stability, peace, and freedom. Third, and finally, the Jews are treated, in the Essai , in exactly the same way as other ethnic groups. Both branches of the original white race, the Hamite and the Semite, were vigorous in their beginnings, but both had degenerated through centuries of interbreeding with black and yellow peoples. Thus, in its disparaging view of modern mankind, the Essai never singles out the Jews. In fact, Gobineau salutes the ancient Hebrews as "a people gifted in everything they undertook, a free people, a

strong people, an intelligent people which, before bravely losing, arms in hand, the title of independent nation, had given the world almost as many scholars as merchants."[17]

So what is the Essai ? It is a somber epic on the origins and history of mankind, prompted, like all fiction, by its author's psychic needs. Raised on a Legitimist myth, bypassed by the bourgeois monarchy of his time, disgusted by the spectacle of the 1848 Revolution, and tormented by his own origins, Gobineau saved his sanity by finding the world sick, even moribund. According to him the explanation of man's present condition is to be found in the past, and the first books of the Essai offer such an explanation, a priori, with a superb contempt for scientific induction. Having confronted the mortality of civilizations and their inequality in the past as well as in the present and having eliminated one by one all institutional and environmental causes, Gobineau focuses on the notion of genetic leveling among races originally unequal.

Did Gobineau believe in the superiority of the white race? In its original state , yes. Yes, when it came to dynamism and to a certain mixture of altruism and practicality, the qualities in which he saw the best guarantees of lasting civilization. The two other races, however, had their own strengths, which made miscegenation a partial gain.[18] Blacks had intuition and artistic instinct,[19] but they were passive. Gobineau wrote later that they embodied the feminine principle.[20] The yellow race was materialistic, tenacious, and diligent, but unimaginative. It embodied the masculine principle. The special greatness of the white race came from the fact that, masculine in origin, it had been strong enough to expand and to integrate the complementary principles of other races while keeping its momentum long enough to flourish. For example, the Sistine Chapel would not exist if blacks had not intermarried with the Assyrian and Egyptian civilizations, which are the mothers of ours.[21] Nonetheless,

the white race, too, eventually declined through this process, for if miscegenation strengthened the weak, in the long run it weakened the strong. It was an ambiguous message and a harsh vision: one pays a price for everything, even for success.

The subsequent books of the Essai develop a somber script. In Book II, Gobineau tells how the Hamites (now become black through intermarriage with the people they had vanquished) mixed with the white Semites, thus causing the decadence of Egypt but also the birth of arts and poetry, and in Book III, how the white Aryans, whose name meant "honorable" and who came originally from the plateaus of Central Asia, conquered China (where they were overwhelmed by the yellow populations) and India (in the south of which they were penetrated by black elements). Book IV focuses on the most ancient white populations in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, including the Greeks, and Book V, on the beginnings of Western Europe, ending with the grandeur and decadence of Rome. Book VI takes up what Gobineau considered the true "Western civilization," that is, Germanic, as it had been several centuries before Christ, and appends two chapters on America, vilipending the Anglo-Saxons both for their genocide of the Indians and blacks and for their illusory democratic regime (his challenge to Tocqueville). Finally, the "Conclusion générale " recapitulates this grim panorama and evokes its logical consequences in a great prophetic vision: the modern human species shall become but the tasteless, colorless, fiberless product, the caput mortuum , of an endless mixing of blood, characterless, futureless—but equal in all its parts.

On balance, is Gobineau a racist? Yes, in a nineteenth-century way, that is, imbued with the notion of differences and with the assumption of an initial inequality among races and prejudiced as to the canon of physical beauty (although the odious description of the black type in the Essai is of-

ten contradicted by the traveler's impressions in Trois ans en Asie ).[22] Yes, in the sense that he considered genetic factors as decisive and sufficient and that he underrated environmental ones in the destiny of nations and individuals. But he was not a racist in our modern sense, first, because in his view all races had, by his time, degenerated, and second, because he never implied hatred or hinted at genocide. "A society is in itself neither good nor evil; neither wise nor foolish; it is." Races were comparable to oaks or grass which "occupy each its place in vegetal series" and whose strength or weakness is therefore no cause for pride or contempt.[23] After Ancillon and Herder and before Spengler and (why not?) Lévi-Strauss, Gobineau's thesis implied the respect for diversity that our egalitarian and homogenizing culture may have lost.

Scientifically, was all this extravagance? In the light of twentieth-century anthropology and ethnology, assuredly. Gobineau had access to the science of his time, though not always at first hand. His footnotes sometimes amounted to mere name-dropping. But his vehemence and a sort of ontological persecution complex account even more for his lack of objectivity. For he sensed that he had been beached on disenchanted shores after the wreck of a whole world, his world, whose roots were to be found in the Aristotelian order of nature. All species had been created simultaneously and ever after coexisted harmoniously in "the Great Chain of Being." The "Reigns of Nature" (to use Buffon's words) constituted "a whole forever alive, forever unchanging."[24] The evolutionary hypothesis (widely promulgated since the eighteenth century and fought to the bitter end by Gobineau) played havoc with the essential, atemporal perfection of nature. So had the history of Man, by stirring the original distribution of human races. Gobineau's "syndrome," then, was a more ontological and epistemological variation of the romantic mal du siècle , and it explains his particular kind of apocalypticism.

The idea of the life and death of civilizations was common to almost all great nineteenth-century syntheses. Long before Valéry borrowed the theme from Gobineau's Essai , Vico, Saint-Simon, Ballanche, Herder, Hegel, and Michelet (to name but a few) proposed this application of the organic model to history. But most saw it in the light of cycles of regeneration and ultimate progress. What characterizes Gobineau is the death wish at the core of his vision: "Mankind [i.e. , man as the product of history] is sick, therefore it will die," but also, "Mankind is degenerate, therefore guilty, therefore it must die." Consequently, unlike its romantic counterpart, Gobineau's apocalypse does not feature clashing planets, or falling stars, or the voice from "the Mouth of Darkness." It does not intimate the survival of the spirit. Instead, the earth is left a barren swamp in which helpless herds of ruminants (Gobineau's last metaphor for the human race) will forever stagnate in torpid stupidity, an unusually materialistic statement for that time.

"Relentlessly to Reproduce Human Nature"[en25]"Relentlessly to Reproduce Human Nature"[25]

This may seem a long preamble to stories that are delightfully aerial; but in addition to trying to alter any a priori resistance to their author, its aim is to help in reading them more accurately, for, in substance and in form, the stories are inseparable from Gobineau's philosophy. He read widely in natural history while writing the Essai ; the two volumes refer to thirty-five such sources and in a few cases (Prichard, Cuvier, Blumenbach, von Humboldt, Flourens, Carus) repeatedly. These readings confirm a lifelong interest in the natural sciences, particularly in zoology and physiology, that is already evidenced in his daily life (he adored and collected animals), choice of friends and acquaintances (zoologists, ecologists, explorers), and correspondence. And in

our opinion this accounts for what makes him profoundly different from the romantic generation with which he otherwise shares a number of standard themes, such as the myth of a distant golden age, the cult of the Middle Ages, and the passion for exoticism. There is no reason to deny that these also exist in Gobineau's fiction, and his works have often been explained from these points of view. But his "zoophilia" led to a "zoomorphism": instead of referring to a vague and idealistic nature, as do many romantics, his imaginary world is perfused with the forces and principles that regulate a realistic biological world.

In the first place, Gobineau approaches human groups and their milieus with the same kind of interest naturalists bring to the observation of species and specimens. In Les Pléiades , he poked fun at the Princess of Woerbeck, who divided society into animal castes: great mammals, lesser quadrupeds, birds, fish and, finally, insects. But this is more or less the way he himself saw society, except that ruminants often joined ants and termites at the lower end of his private bestiary. The Princess, of course, based her categories on rank, while Gobineau based his on energy, vitality, and honor. The First Empire court and business world in "Mademoiselle Irnois," the Persian bazaars of "The War with the Turcomans," and Madame de Hermannsburg's boudoir in "Adélaïde" remind one not only of a morphologist's collection, which records outward features, but also of an ethologist's field notes. The Naxiotes in "Akrivie Phrangopoulo" are presented as an endangered species, an older form of life preserved by geographical isolation: Naxos is Gobineau's Galapagos.

Because these milieus are depicted as biological, their inhabitants are driven by universal forces that transcend the particular social group and often tear through its tissue. The silky salons in "Adélaïde" become jungles in which chandeliers throw the same cruel and indifferent light on the pas-

sions as would an African sun on the fight of great cats. Under the oriental flourishes of Gobineau's prose in "Turcomans" run primitive instincts: aggression, attachment, fear, jealousy, self-defense. This is a world in which females have the strength, the resourcefulness, and the initiative in sexual selection given them by nature, in which the signs of emotions (blushing, pallor, grinding of teeth, stamping, contractions, dilated nostrils) are more eloquent than their verbal expressions, in which lushness of hair, freedom of stride, and intensity of the eyes advertise the alpha-animals and their opposites, the weak. It is a world in which submission and domination are conveyed by ritual gestures, in which the seeking and securing of a mate (to whom one will be bonded) is never confused with sentimentality or eroticism.

Again, passion or violence alone would make Gobineau no more than a typical romantic writer. But one mark of romanticism is that passions are the prerogative of extraordinary individuals, whom they raise above ordinary men. This is not so in Gobineau, for whom they are simply the behavior of what he often calls natures or créatures (also, sometimes, constitutions or constructions ). As such, they are always innocent, but also unheroic. In this respect, even the much discussed elite of his Pléiades (the gentlemanly "happy few" of his best-known novel) need to be redefined: regardless of their moral struggles, their arrival at a higher moral plane results from the normal trajectory of their nature. Undoubtedly, this makes them more predictable as characters (a reproach sometimes addressed to their creator),[26] but they act, move, and speak with the self-assurance of instinct. Gobineau's characters are never embarrassed by their own contradictions or philosophically concerned about life's contradictions. They are survivors, above all. Emmelina Irnois shows what happens when instinct is derailed. The magnificent way the narrator of "The War with the Turcomans" cheats his officers, goes through wars, coexists with con-

querors, adjusts to polyandry, in which Adélaïde and her mother maintain their respective territories so as to prevent the defeat of either—all this amounts to an ecology. Nature always finds its path, always lands on its feet. Through his narrator, Gobineau says it in his own way at the end of "Adélaïde": "If it were a novel that I am telling you about, I would tranquilly have one and the other [women] die here of exhaustion, shame, and grief. There would be reason enough. But, not at all. Things rarely end this way in real life."

Gobineau's fiction also owes much of its form to an organic model and to the priority given by his system of values to nature over culture. A series of literary articles he wrote for periodicals between 1842 and 1847 are revealing.[27] The qualities he most often praises in, or requires of, other writers are expressed in terms of warmth, energy, rapidity, vigor, ardor, mettle, verve, freedom—in other words, the characteristics one normally associates with the higher orders of animals. And these qualities are precisely what shine in the composition and style of his own fiction. With strong, unrestrained openings that move rapidly to the core of the tale, sudden, brief, often anticlimactic closures à la Chekhov, and unelaborated or absent transitions (this last trait, of course, more evident in his novels than in his short stories), Gobineau's narratives simulate the prompt attack and flight of animals in the wild. Each tale has its own pace. "Adélaïde" uncoils, "Turcomans" trots along, "Mademoiselle Irnois" crawls, "A Traveling Life" advances with the charming (or exasperating) capriciousness of a caravan, "Akrivie Phrangopoulo" digresses through an excursion to Santorini at the end of which Norton's decision to cross this Greek Rubicon surprises not by its substance but by its suddenness—loose composition for a genre (the short story) that in itself showed a predilection for the discontinuous and heterogeneous.

The authors in Gobineau's empyrean were Stendhal (appreciated as a brilliant observer), Balzac (because, unlike

Gautier, he escaped the curiomania of a commissaire-priseur —"antique auctioneer"), Musset (when he overcame his mal du siècle ), but primarily those classic writers whom he perceived as unself-consciously realistic. He always showed a great mistrust of words and, in the long run, considered deliberate stylistic features as an obstacle to the transparency of the subject, which he felt necessary to the recovery of truth. In our era, when most intellectual production is analyzed from the point of view of a radical idealism, this "core realism" at the center of Gobineau's aesthetic beliefs might seem a naive position to take in the same general period that Flaubert was confiding to Louise Colet his ambition to create a self-sufficient literary object that "would exist by virtue of the mere internal strength of its style"[28] and would replace, even void, the world of referents.

In this respect a strange thing happens: Gobineau often re-creates objects that impose themselves on the reader with the same hallucinatory presence as Charles Bovary's immortal headgear. Only one does not perceive the author's labor in the text, which, on the contrary, has an air of felicitous negligence. And he was negligent, writing fast (his masterpiece "Adélaïde" was written in one day), with the casualness characteristic of an aristocrat indulging in a hobby. Let us look, for instance, at the description of Akrivie's hair (pp. 118–119 in our translation): "Une coiffure mordorée, épaisse, abondante, tordue et semblait-il, avec quelque impatience de la peine qu'elle donnait pour la soumettre, bien que plus fine que la soie et souple à miracle." It does not hold together syntactically. First, the conjunction et should not separate avec quelque impatience from tordue , which it modifies; second, it is odd that the third person pronoun la suddenly introduces an outside subject, the person presumably for whom "it seems," who experiences impatience but is distinct from the grammatical subject elle (the hair); third, the last member of this little monster, bien que plus fine , and

so on, brings us back to elle (the hair), while we were by then focusing on the "hairdresser." This is an anarchic sentence in which the hair and imaginary person arranging it (Akrivie herself, in all probability) are encroaching on one another's grammatical territory; but the quasi-miraculous effect is that of a tug-of-war in which the "comber" (culture) is defeated by this animalistic, elusive, and triumphant mass of hair (nature). In other words, we have here a definite literary object consistent with the story's main theme, even though Gobineau made it virtually unbeknownst to himself, as Molière's Monsieur Jourdain spoke prose.

Gobineau himself, however, occasionally mounted the hobbyhorse of literary theory and issued dutiful statements about both the necessity for literature neither to improve on nor to imitate life.[29] He once conceded that perfection of form could redeem any subject, however absurd. Nevertheless, he himself did not write one short story that was not closely connected with his personal experience and his observations in situ. He subtitled the Souvenirs de voyage with the names of three places he had been. He referred to Nouvelles asiatiques as "a way of painting what I have seen"[30] and in his correspondence often dwelled on specific sources and his respect for the truth. Whatever response we may now have to his stories—and they are rich enough to validate a wide range of opinions—he would have resented the hint that his real and fictional worlds are parallel and nonintersecting.

This desire to keep his fiction anchored in the real world partly explains why his tales are always told by a narrator who, as Gobineau proceeded in his career, became not only more and more explicit but more and more complex. Monsieur Irnois "had started from scratch, but that is not what I find astounding," we are told by a self-designating author. However, Gobineau uses the ambiguities of distance that the French on allows to create the ironies of voice of the narrator in "Akrivie Phrangopoulo" who undertakes the visit to

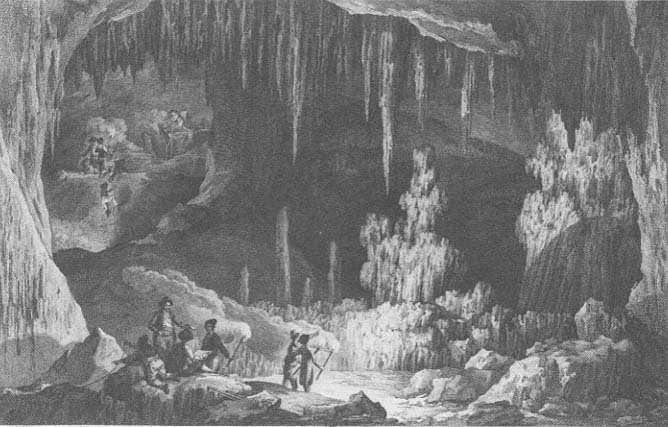

the Antiparos cave. On is in part the Gobineau who was once talked into entering the cave, where he discovered more vulgarity than splendor. It is simultaneously someone else, possibly the voice of a typical tourist (the kind that would leave graffiti) trying to enlist the sympathy of the listener—a closeness and yet a complexity of distance best conveyed by "you" in English: "You have to squeeze foxlike through one of the narrow tunnels. . . .You enter an opaque darkness bent over so as not to break your head." "A Traveling Life" starts with the warning, "It is irrelevant to wonder at this point how and why Valerio Conti. . . ." Again, a listener's query is implied.

Of course, this is not an original trick in short story writing, but Gobineau's version of it is remarkable in the way he finds his own middle ground between the typically eighteenth-century narrator of, say, Tristram Shandy, Jacques le Fataliste , or Tom Jones , who is deliberately deceptive and intrusive, and the typically nineteenth-century narrator, who is reliable and the guarantor of clear societal standards but who lacks real presence. In contrast to these two types, the Gobinian narrator is sincere (if not always reliable, as in "Turcomans") and present, however subtly. Through him, the author speaks to us with an intimacy that amounts to a signature. Few other writers of short stories make the reader as aware of being singled out for a treat. Gobineau's uniqueness may also have to do with the fact that his stories were conceived, possibly tested, and written in periods of his life when he had a built-in audience (while in Athens, Rio de Janeiro, Stockholm). Moreover, as a young man, Gobineau had adored the Arabian Nights and later acquired a copy of the classic Galland translation. To a man not meant for the administrative doldrums, escaping the boredom of uneventful diplomatic jobs might have seemed as pressing as the necessity of saving her neck was for Scheherazade. His contemporaries remember him

as a charming storyteller, an intense and lively reader. At any rate, this assumed friendship between narrator and listener/reader makes Gobineau truer to the oral origins of the genre than many of his contemporaries. Nodier's voice (not his substance) may be the closest to Gobineau's in this respect; what he wrote in defense of his tales, Gobineau could have made his own:

Je suis parleur, dit-on, mais qu'importe le temps?

Je tiens qu'en cet objet c'est la dernière clause,

Pourvu que le lecteur prenne goût à la chose.

Et qui vous dit que je prétends

A conter avec art? Il n'en est rien, je cause![31]

"Those Rogues Who Are More or Less Our Relatives"[en32]"Those Rogues Who Are More or Less Our Relatives"[32]

Although there were other raconteurs in his day, Gobineau felt that with his Asiatic stories, he had "invented something."[33] Unbeknownst to him, that "something" transcended both his literary stature and his scientific errors and prejudices. His comment was probably a response to Barbey d'Aurevilly's complaint about the unimaginative plot of Les Pléiades : "By his function, M. de Gobineau frequents and even rubs shoulders with history; let him give us history, then, but living history."[34] Nineteenth-century history is inseparable from a vast anthropological awakening that had begun in the fifteenth century and was brought home four hundred years later by European colonialism. Gobineau's Nouvelles asiatiques provided the general public the message the Essai had been unable to convey unmitigatedly and positively—the message of human variety. Though his contemporaries, perhaps still unprepared, gave them a tepid reception, their importance has since been perceived. What, indeed, recapitulates the period in these stories is that although the circumstances which underlay them were steeped

in colonialism, they undermine its validity and yield an anticolonial message.

In Gobineau's view, the destiny of the Aryan race had been partly decided in Persia where, descending from the Pamir range, it mixed with disparate (and inferior) racial elements. Gobineau wrote to Prokesch-Osten that, the contemporary world being irreversibly "afflicted with senility," he wanted to show in Nouvelles asiatiques "what good and evil meant in the mores of a decayed people"[35] —an effort that none of these stories nor any of the volumes resulting from his sojourn in Persia (of which Trois ans en Asie and Religions and philosophies dans l'Asie Centrale are the most important) seems to demonstrate. Indeed, his introduction to the Asiatiques , written later (1874) than the stories themselves, states:

Unlike what moralists teach us, men are nowhere the same. . . .It is because men are everywhere essentially different—in their passions, their views, their ways of seeing themselves and others, their beliefs, their concerns, the problems in which they are engaged—that studying them is so diversely and keenly interesting and that it is so important to devote oneself to that study if one wants to understand at all the role men—and not Man—play in creation. That is what gives history its validity, poetry some of its merit and fiction its sole raison d'être.[36]

For anyone interested in contemporary Islam, Trois ans en Asie , published in 1859 and unfortunately still not translated into English, remains essential reading. The first and last sections of the volume tell of the Gobineau's ill-fated first sojourn in Persia. The second section is a systematic analysis of administration, religion, and social hierarchy. The tourist's delight in colorful sights has given way to a penetrating observation of the Persian soul. Trois ans en Asie and Nouvelles Asiatiques are tightly meshed: the talent of the raconteur, who is at the center of the stories, gives the travelogue its special warmth, and all of the substance of the

stories comes from Gobineau's experience of Asia, not all of it firsthand (he was familiar primarily with Teheran and the regions north of it). But it was his spiritual itinerary that was, finally, the most important element.

Prior to the nineteenth century, Europeans knew Persia through Chardin and Montesquieu and through Rameau and Mozart. They viewed Islam through Molière's turqueries and Voltaire's Mahomet . As a transition between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Volney represents an interesting hybrid of history and literature. In fact, he criticized (in his Simplification des langues orientales )[37] his compatriots' linguistic ignorance, which barred them from any understanding of the Orient. It seems that later on the Orient motivated very different kinds of works. On the one hand, oriental scholarship flourished with the cuneiform pioneers: Rawlinson, Niebuhr, Burnouf, Lassen, and Botta (who excavated the Khorsabad inscriptions in Iraq in 1842 and 1851). Gobineau knew of these researches (in many cases through Jules Mohl and the Journal asiatiques ) and used them in the Essai . On the other hand, the voyage en Orient became a literary genre to which not only Chateaubriand, Nerval, Du Camp, and Loti, but also less poetic and equally unreliable voyagers such as Morier, Ferrier, and Flandin succumbed.[38]

But in spite of the recent (and legitimate) discrediting of the notion of "Orient" as a European imperialist invention —"a certain will or intention to understand, in some cases to control, manipulate, even to incorporate what is a manifestly different (or alternative and novel) world"[39] —Gobineau's testimony remains valid. Trois ans makes clear why this is so. In the introduction to the second section, Gobineau wrote, "I have tried to repudiate completely any idea, whether correct or not, of our superiority over the people I was studying. As much as possible, I wanted to see things from their various points of view."[40] We find a poetic version of the same guiding principle in "A Traveling Life":

"The art of traveling is no more given to everyone than the art of loving, or understanding, or feeling." Particularly during his second sojourn in Persia, Gobineau put these ideals into practice by means of serious study, which led him to exclaim: "I am astonished, not to say frightened, by the depth of life in these Oriental nations, especially when I compare them to the moral torpor and reckless materialism of European thought."[41] So the Persians, those fallen Aryans, were not decadent after all. Their nobility showed in their sobriety, in their sense of the spiritual dimensions of life, even in their superb roguishness.

The depth of Gobineau's oriental studies remains a point of contention among scholars. His assessments of the Shiite and Sufi philosophies may lack complexity, but the books they produced still speak to the spirit, if not the letter, of Islam. Gobineau was, in fact, prophetic about the future of Iran when he wrote:

As Persians are Shiite and acknowledge only Ali as their legitimate caliph . . . the Shah maintains himself only by violence. The race [sic] of Imams is considered as still alive. . . .The Imamate can therefore reveal itself at any time in the person of an unknown man. Then this man will be the legitimate sovereign and his right to be so will be unchallengeable.[42]

And he had no less foresight when it came to the future of colonial empires. At a time when Vigny was writing bellicose pieces on the conquest of Algeria and Du Camp was celebrating the steam engine, Gobineau's skepticism in the matter is striking in its sophistication:

For the last 30 years you have heard much in our country about civilizing the other people of the world. . . .No matter how hard I look, I cannot say that in modern times the French have civilized the Canadians, or the Pondichery Hindus, or the Moors in Algiers; nor that the English have changed the ways of their subjects in India, nor the Dutch transformed

the Javanese people, nor the Russians the Caucasians. Confronted by a failure that persistent, it is wise to suspend one's judgment about success.[43]

"Handle Prose As You Would Verse"[en44]"Handle Prose As You Would Verse"[44]

As a genre short fiction has a voluminous and confusing history[45] bristling with contradictions and overlapping definitions of what constitutes the conte, nouvelle , and novelle , not to mention less ubiquitous forms such as the fabliau, histoire, historiette , and anecdote . There is some agreement that the conte is a whimsical, sometimes fantastic, narrowly focused, closed-ended narration, whereas the nouvelle is more complex, sequential, and open-ended. But most critics, it seems, state the definitions only to disprove them immediately. Some of the finest writers in the genre such as Marmontel, Diderot, Goethe, Schlegel, Tieck, Nodier, Mérimée, and Maupassant, did not adhere to these definitions, although they often were the ones who theorized on the subject. Diderot, who categorized the conte as merveilleux (fibbing), plaisant (entertaining), or historique (true to life and moralizing),[46] hastened to entitle one of his own productions Ceci n'est pas un conte. Adolphe , now considered a novel, was called a nouvelle when it appeared. Balzac and Maupassant chose the word conte for their short stories, and Nodier used indifferently conte, nouvelle, historiette, anecdote , and even roman . Gobineau always referred to his short fictions as nouvelles. The game of terminology, however, quickly reaches a point of diminishing returns. What is more relevant is to situate Gobineau's short fiction against a historical backdrop of substantial and formal requirements, and not in terms of labels.

The eighteenth century had already elevated short fiction to the status of servant to the philosophical goals of

the Enlightenment. For a number of reasons having to do, basically, with the substance of romanticism, the nineteenth century went further, making the nouvelle—or conte—a major genre. The chasm between the individual and society, one of romanticism's major themes, is perhaps most cogently explained by Lukács as the increasing alienation of the individual in the midst of an increasingly capitalistic economy and as the internalization of the notion of an ordered world.[47] Thus, short fiction would compensate for the apparent disorder of the world by the rigorous discipline required of the form. It may not be a coincidence, then, that The Decameron and Arabian Nights , those models of models, are supposedly prompted by states of emergency—by the plague in Florence and by the threat hanging over Scheherazade's life.

With the isolation of the individual came marginality, and with it, literature opened its doors to another face of the world—a face that eighteenth-century mystical philosophy (through Swedenborg, Pasqually, and Saint-Martin) had already provided glimpses of. There again, in the romantic period, short fiction was particularly apt at conveying the irrational, or the bizarre, because its tightness forces an emphasis on phenomena rather than on causes, thereby casting an aura of mystery over its various moments—as ordinary as they might first appear. Goethe was the first to assign the short story the task of "accrediting the unusual" when he required that it be based on a paradoxical, "unheard of event which has really taken place" (unerhörte Begebenheit ).[48] Finally, this "other face of the world" could also be the past or the far away, whence the romantic predilection for the historical and the exotic, which, particularly in the first half of the nineteenth century, the short story demonstrates.

If this was the literary context in which Gobineau wrote, to what extent did it affect his fiction? Comparatively little, it seems. In his system of values, man was too much part of nature and society, too transient a phenomenon, for

alienation to occupy a central place in his literary world. For one who thought that "man is a newcomer in the world" and that "geology registers his absence from all early formations of the earth and has never found him among fossils,"[49] society cannot command the occult power that it does in the works of Merimée, for instance, where it accounts for the autocratic societal "one." Inasmuch as Merimée's heroes live in the shadow of this "one," as if fallen from some grace, we might say that his fiction, in contrast to Gobineau's relatively guiltless world, has a Jansenist ring. Moreover, there is little trace of the fantastic in Gobineau's stories, probably because the religiosity on which it rests made little dent in his self-avowed (if not self-advertised) agnosticism.

Gobineau's aversion to the fantastic may also be related to his stand on evolution and the controversy swirling around it, just as the eighteenth century's fascination with monsters revealed a belief that anything could happen in nature. By demonstrating the looseness of the concept of species, freaks betrayed a rampant evolutionism. But, as a disciple of Cuvier, Gobineau postulated the absolute fixity of species. The consequence for his literary world is a lack of interest in marginal beings and happenings. His creatures stay within the type; his behaviors, within that of the species. His admiration for the Moslem mystics (evident in L'Illustre magicien ) is more an oblique criticism of European materialistic mediocrity than an espousal of mysticism per se, as illustrated by the reunion of the lovers at the end. Their energy counted more than their faith. Finally, romantic primitivism or exoticism leaned on an accumulation of technical details that Gobineau despised, intent as he was on conjuring up mentalities rather than props. It has been suggested that the Essai would lend itself to a superb tragicomic strip.[50] Possibly. The subtlety of his short fiction, on the other hand, presents an interesting challenge to film adapters.

One might praise Gobineau for not adding to the long list of standard romantic tales such as came from the pens of Nodier, Gautier, Dumas, for instance. But his rejection of this form shows his limitations as well as his strengths. For from the same stock came the German novellen and the Russian short stories of Gogol, Dostoevski, and Chekhov whose metaphysical dimension is the cradle of modern literature. It is cosmic and unknown forces, no longer societal ones, that surround Kleist's characters and ridicule their rational schemes, thus prefiguring Camus's absurd. His heroes, who reckon with these forces and survive, are no different from Sisyphus. The cosmos dwarfs man's activities, but these activities in turn challenge the blind universe—a contemporary article of faith that is strikingly illustrated in Waiting for Godot but that was already present in Gogol's Overcoat . The fissured being evidenced in the romantic doppelgänger is further displaced and reduced (but also stubbornly salvaged) in Kafka's beetle and designates the repossession of the self as one of the major modernistic endeavors. Poe, whose obsession with the enigmatic announces the existential renunciation of understanding the universe, represents another shade of this spectrum.

French short fiction writers themselves did not entirely escape this occultation of literature, even though Heine denied that "France was a favorable ground for such ghosts"[51] and that the horrible could be cultivated by French writers. But Maupassant and Villiers (both contemporaries of Gobineau) prove the opposite. By imperturbably pushing logic to its end in La Maison Tellier , Maupassant approximates the fantastic in a way that sabotages human institutions. The relentless cruelty of L'Aveugle , which is built around an absence (the gap of the blank eyes) and ends with another (the disappearance of the Blind Man's body), becomes a permanent denunciation of a void in our society. Villiers, whose characters have been compared to "wayfarers vainly stirring

amid shadows,"[52] is also a pioneer of the twilight zone. We miss such proximity to the abyss in Gobineau. If the history of short fiction is a vast landscape in which the watershed is the beginning of an "era of suspicion," Gobineau remains suspiciously on its nonsuspecting side.

Gobineau's offering to literature is of another kind and is connected with his vision of the natural world as not inscribed in time. His inability to accept the causal and sequential structure of evolution makes him both a vestige of another era and the rescuer of a synchronistic view of nature lost to the modern world. This had a direct connection with his fiction, as one of his closest friends, Prokesch-Osten, pointed out: "I have been enchanted by your short stories. It is a novel and correct way to write history , that is to depict . . . what in man is essential and stable . . . and to do so outside of these eternal struggles produced by vanity and passions involved in what one calls history ."[53] The distinction Prokesch-Osten makes between the two histories of man, the man-made one and the natural , seems, in our view, to be as central to Gobineau's fiction as it is to the Essai . It can be called classicism. All classicism, especially that of the grand siècle , uses the immutability of human nature as an alibi for social and political conservatism, and, on the whole, Gobineau did not escape this rule. Yet, another consequence of this obsoleteness is that Gobineau speaks with a clarity that comes only from an unquestioned universe in which "the words and the things" (to use a contemporary notion) did not intimate their divorce. But today's reader, who suffers under an imperialism of ambiguity, may find the transparency and straightforwardness of Gobineau's stories a welcome relief from Merimée's grim motto: "Remember to distrust" (

Gobineau described himself as "a poor fellow from the eighteenth century fallen into ours by a fluke I shall never be able to explain to myself."[54] In his day, he demonstrated a

certain flair in appreciating Heine, Stendhal, and Sand, but he hardly seemed to notice such illustrious contemporaries as Flaubert, Maupassant, Villiers, and Zola. Rather than look to the nineteenth century to find Gobineau's soul mates in the world of letters, we might look to authors with eighteenth-century spirits but presaging the nineteenth century. Diderot (in his tales), Byron (in his poetry and his correspondence) are examples; intuition, scientific and philosophical in the first case and political and aesthetic in the second, carried both writers ahead of their time and, in fact, made them more modern than Gobineau. Yet, like Gobineau, both spoke with the graceful clarity of one who is at ease with the world and himself.

Thus, Gobineau's short fictions succeed where his poetry fails. They have the wholeness of poems. Their apparent lack of sophistication and their matter-of-factness give these stories, paradoxically, the same elusive aura that usually is present in more ambiguous fictions. This is the "margin" Max Jacob found only in some Japanese and Persian poems and (precisely) in Gobineau's stories;[55] it may allow them (as in Archibald MacLeish's famous phrase) to "be" rather than to "mean." The Gobineau who reminded us that "works of art are meant to appeal not only to the mind and the critical faculty but above all, to the heart, the temperament, to whatever those who read them, see them, or hear them are made of" would not, we think, disown this last brush stroke on the portrait.

A. S.

D. S.

Mademoiselle Irnois

I

M. Pierre-André Irnois was one of those money dealers who succeeded best in making their fortunes under the Republic.[1] Without attaining the quasi-fabulous splendors of an Ouvrard,[2] M. Irnois became quite opulent, and, what especially distinguished him from his peers is that he had a knack for preserving his wealth; in brief, he did not imitate Hannibal: first he knew how to vanquish, then to preserve his victory; his breed, had it endured, could have compared him to Augustus. In his sphere, his rise had been even more astonishing than that of Caesar's adoptive son. M. Irnois had started from nothing, though that is not what I find astounding; but rather that he had not the slightest trace of talent; nor did he have the slightest trace of shrewdness. He was at best a mediocre rascal; as for insinuating himself into the company of the mighty or the lowly in order to secure useful favors, he had never given it a thought, being much too brutal, which in his case replaced dignity. Awkwardly put together, tall, thin, dry, sallow, provided with a huge, ill-furnished mouth whose massive jaw would have been a formidable weapon in a hand like that of the Hebrew Hercules, he offered nothing in his person of a nature sufficiently appealing to make one forget the flaws of his character and those of his intelligence. Thus, materially and morally,

M. Pierre-André Irnois did not possess the means to make one understand how he had been able to achieve enormous wealth and to join the ranks of the powerful and fortunate. And yet, he had come to own six town houses in Paris, improved farmlands in Anjou, Poitou, Languedoc, Flanders, Dauphiné and Burgundy, two factories in Alsace, and coupons for all public bonds, the whole crowned by unlimited credit. The origin of so much wealth could only be explained by the strange caprices of destiny.

M. Irnois, I already said, was of very humble birth; everyone, at any rate, believed it, and he along with the rest; but, in fact, nothing was known about it. He had never been aware of a father or a mother, and he had begun his career in the livery of a scullion in the kitchen of a respectable Parisian bourgeois. From there, fired for having let a roast burn that had been put in his care for a gala occasion, he had wandered for some time, a victim of the melancholy ups and downs of vagrancy. The poor devil had subsequently got hold of a job as a footman in the house of a barrister and, soon dismissed for being too impertinent and a bit of a thief, he very nearly died of starvation one fatal night when the watch picked him up, expiring from want of nourishment, under one of the pillars of the Central Market where he had dragged himself after having vainly looked for unmentionable scraps in the neighboring rubbish heaps.[3]

They wanted to send him to the Islands.[4] He escaped, hid himself in the garden of a lady philosopher and philanthropist, and, when discovered, told his story. By chance, that lady had gathered around her that very day several dinner guests, among them M. Diderot, M. Rousseau from Geneva, and M. Grimm.[5]

The ragged vagabond's tale served as a timely text for various considerations, alas only too accurate, concerning the social order. M. Rousseau from Geneva publicly embraced Irnois calling him his brother; M. Diderot also called him