Preferred Citation: Dunleavy, Janet Egleson, and Gareth W. Dunleavy Douglas Hyde: A Maker of Modern Ireland. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2w1004tq/

| Douglas Hyde: |

For Henry J. Dunleavy

In Memoriam

Preferred Citation: Dunleavy, Janet Egleson, and Gareth W. Dunleavy Douglas Hyde: A Maker of Modern Ireland. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2w1004tq/

For Henry J. Dunleavy

In Memoriam

Acknowledgments

For assistance with this study of the public and private life of Douglas Hyde, we are indebted first of all to Sean O'Luing, biographer, translator, poet, and friend, who one August day in 1978 stopped us on the steps of the National Library of Ireland and urged that we undertake this task. The following day, on these same steps, he placed in our hands two shopping bags full of Hyde materials—letters, interviews, cuttings, manuscripts, notes—that he had patiently gathered over the years. At every turn, this book bears witness to his invaluable gift and continuing encouragement and advice.

To the executors of the Douglas Hyde estate, to his late daughter, Una Hyde Sealy, and to all his living heirs, we owe a special debt, not only for their generosity in providing access to family holdings, answering hundreds of inquiries, and permitting us to quote from Hyde materials, but also for their friendship.

We are deeply grateful for the support we have had from the American Council of Learned Societies, American Irish Foundation, American Philosophical Society, Camargo Foundation, John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, and College of Letters and Science and Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee which has made our work possible. We wish also to thank Bernard Benstock, Shari Benstock, John Halperin, Eric Hamp, Fred Harvey Harrington, Ann Saddlemyer, David H. Greene, Alf MacLochlainn, T. Kevin Mallen, William Roselle, and William V. Shannon, whose confidence, expressed at critical junctures in this project, guaranteed its completion.

We sincerely appreciate the help we have received from scholars, archivists, and others in England, Ireland, Canada, and the United States whose special knowledge of or access to much-needed information was often crucial to us. Among those who patiently answered our many questions on aspects of written and spoken Irish and Hiberno-English, on the nuances of Irish culture, and on lesser-known facts of local and national Irish history were Bo Almquist, Dan Binchy, Richard J. Byrne, James Carney, Tomás de Bhaldraithe, Pádraig de Brun, Bernard Finan, Dorothy Fox, David Greene, Thomas Hachey, Maura Harmon, Maurice Harmon, Patrick Henchy, Michael Hewson, Richard M. Kain, Mary Lavin, James Liddy, Gerard Long, John Lyons, M.D., Eoin MacKiernan, Fionnuala MacLochlainn, Deirdre McMahon, Maureen Murphy, Breandán Ó Conaire, Tomás Ó Concannon, Betty O'Connell, Maurice O'Connell, Daithi Ó hÓgain, D.S.O Luanaigh, Tomás Ó Maille, Nessa ní Sheaghdha, T. P. O'Neill, Brid O'Siadhail, Micheal O'Siadhail, Bruce Rosenberg, Michael MacDonald Scott, Colin Smythe, and Christopher Townely.

Our thanks are due also to those who facilitated our research in special subjects and assisted us in other areas of professional expertise, especially Jeanne Aber, Lance J. Bauer, Alan M. Cohn, Pierre Deflaux, John P. Ferré, James Ford, Patrick Ford, Howard Gotlieb, Herbert Kenny, Helen Landreth, Judith Livingston, Ciaran McGonigle, William Moritz, Catherine Murphy, Michael Pretina, Henry Siaud, Lola Szladits, Raymond Teichman, Alan Ward, and Russell Young.

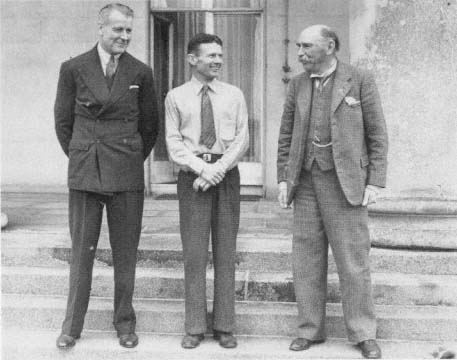

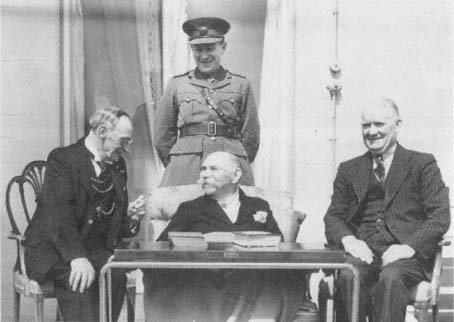

From 1978 to 1989, as we steadily expanded the combined collection of notes and documents presented to us by Sean O'Luing and previously accumulated by us in connection with earlier projects, we were fortunate to have the help of scores of men and women acquainted with Hyde himself, his life and times, and his achievements. Among those who shared with us their personal recollections, correspondence, and memorabilia were Colonel Thomas Manning and Colonel Eamon de Buitléar, aides-de-camp to Douglas Hyde, and their families; Desmond McDunphy, Eileen Monahan, and Brenda Warran-Smith, whose father, Michael McDunphy, held the office of secretary to the president during and after Hyde's presidential term; Erskine Childers, former president of Ireland; members of the family of the O'Conors of Clonalis, especially the Reverend Charles O'Conor Don, S.J., Josephine O'Conor, Eva Staunton, Captain Maurice Staunton, Gertrude Nash, and Group Captain Rupert Nash; The Macdermot, Madame Macdermot, and other members of the family of the Macdermots of Coolavin; Thomas

Kilgallen, M.D., of Boyle, physician to Lucy Hyde; members of Hyde's household staff at Ratra, including Carrie and Tom Mahon, Annie Mahon, and Peter Morrisroe; Bob Connolly, sexton, Church of Portahard; Hyde's American friend Ben Greenwald; and a number of Hyde's former students, including Dan Bryan, Eileen Gannon, Christine Keating, and Liam MacMeanman. President Erskine Childers showed us through the state rooms of Áras an Uachtaráin and described their appearance when Hyde was in residence; President Patrick Hillery authorized a second visit that enabled us to recheck specific details; Ambassador William V. Shannon and his wife, Elizabeth Shannon, answered our questions about the presidency, American-Irish relations, and the history of the official residences in Phoenix Park.

In north Roscommon and Sligo we talked extensively with men and women whose local memories of people, places, and events were significant to the life of Douglas Hyde. Kate Martin and the late Bertie MacMaster of Kilmactranny shared with us facts about Hyde's birthplace and local recollections of members of the family of the Reverend Arthur Hyde, Jr., who once made their home there. Pa Burke, for many years the oldest living resident of Castlerea, recalled for us his first Irish lessons in the early days of the Gaelic League. Michael Cooney reminisced about the Frenchpark in which he had lived as a boy at the turn of the century. Tommy and Mary Bruen, Kevin and Margaret Dockery, and Mick and Peggy Ward shared their knowledge of the oral tradition of north Roscommon as it pertained to local families and to local geography, including place-names. The Reverend Robert Holtby and Mrs. Maud Holtby searched Church of Ireland records for both Kilkeevan and Portahard for details concerning dates and events. And dozens of other current and former residents of Roscommon, Sligo, Leitrim, Galway, and Mayo whom we met informally in the course of our research—in shops, in pubs, walking along country roads—contributed family memories, anecdotes, tales of local interest, and little-known facts of local history to our store.

Among private collectors of Hyde's books and papers, we are indebted to the late Captain Tadgh MacGlinchey, Ciaran MacGlinchey, Aidan Heavey, the Trustees of the O'Conor Papers at Clonalis House, and others who prefer to remain anonymous. Hyde figured largely of course in other private collections as well. Maeve Morris gave us copies of Hyde items in the Henry Morris Papers. Francis Barrett supplied information about the Trinity College Historical Society. C. Joseph Neusse, Provost Emeritus, Catholic University, contributed informa-

tion concerning Hyde's visits to Washington, D.C. Geraldine Willis searched the archives of the Representative Church Body. William Flynn, Beverly Goldner, Desmond MacNamara, Frank Martin, and John Woolsey tapped other sources, including their own experiences and memories, to provide a range of perspectives on Hyde himself, his life and times, and his family background. Among representatives of the media in Ireland and Irish booksellers who frequently extended themselves on our behalf, we think particularly Andrew Hamilton, Caroline Walsh, and Conor Brady of the Irish Times ; the late Michael O'Callaghan of the Roscommon Herald ; Padraig O'Reilly and James Fahy of Radio Teilifís Éireann; and the Kenny family of Kenny's Book Shop in Galway.

For permission to consult holdings and for assistance in using research materials and facilities we are indebted to administrators and staff members of the following libraries and archives:

In the United States : the Boston Public Library; Bapst Library of Boston College; Mugar Library of Boston University; Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial Library; Houghton Library of Harvard University; Milwaukee Public Library; National Archives of the United States; Berg Collection and Special Collections of the New York Public Library; Providence (Rhode Island) Public Library; Morris Library of Southern Illinois University; McFarlin Library of the University of Tulsa; University of Wisconsin—Madison library; and Golda Meir Library of the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee.

In Canada : the Harriet Irving Library of the University of New Brunswick.

In France : the University of Haut-Bretagne at Rennes and the regional libraries of Aix-en-Provence, Avignon, Cassis, and Marseilles.

In England : the British Museum Library, Public Records Office, and Postal Archives.

In Ireland : the National Library of Ireland; the libraries of the Royal Irish Academy and the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies; the University College, Dublin, library; the Trinity College, Dublin, library; and the University College, Galway, library; the Archives of the Trinity College, Dublin, College Historical Society and the Department of Folklore, University College, Dublin; the State Papers Office; and the Public Record Office.

In Ireland we profited also from the generous assistance of Peter Beirne of the Kilrush branch of the County Clare Library, Helen Maher and Helen Kilcline of the Roscommon County Library, Nora Niland

of the Sligo County Library and Museum, and the staff of the Sweeney Memorial Library in Kilkee.

In developing our composite portrait of Douglas Hyde we have depended primarily on Hyde's own diaries, letters, mementos, manuscript drafts, and memorabilia and the oral and written testimony of his family, friends, associates, acquaintances, and their heirs. Among the published sources we have consulted for confirmation of dates, facts, and events, for other images of both the private and the public man, and for background, historical context, and multiple perspectives, none has been more useful than Dominic Daly's The Young Douglas Hyde (1974). We recognize that even in our occasional differences we owe much to Daly's pioneer effort; we deeply regret that his untimely death cut short our conversations on subjects of mutual interest in the early stages of our work. Many others named above—including those personally acquainted with Hyde—also have died in the years since 1978. We mourn their passing and regret that they are not alive to see the fruits of their contributions, but we feel privileged to be able to preserve here their memories, observations, and opinions.

In the penultimate stages of our work, Sal Healy of Dublin, Priscilla Diaz-Dorr of Tulsa, and Margaret Kendellan of Milwaukee provided cheerful and thoughtful research assistance. Francey Oscherwitz's queries encouraged sensible revisions.

Finally—for his wisdom, patience, and understanding without which we might never have reached this point—we are deeply indebted to our editor, Scott Mahler.

JANET EGLESON DUNLEAVY

GARETH W. DUNLEAVY

APRIL 1990

1

Douglas Hyde and the Generational Imperative

In an introductory tale to the Táin Bó Cuailnge , or "Cattle Raid of Cooley," Senchán Torpéist, an Irish laureate of the seventh century, convenes the poets of Ireland for the purpose of reconstructing this most famous of Irish epics, the centerpiece of ancient Ireland's mythic and cultural traditions. The poets are unsuccessful. As a last hope one of their number is sent to Gaul to recover what he can from a "certain sage" there. On the way he stops in Connacht, at the grave of Fergus mac Roich, a major figure of the Táin and the last man known to have had the entire narrative in his head. Fergus himself appears; the lost epic is recovered; the tradition is preserved intact.

The concept of a generational link among Irish poets, scholars, heroes, leaders—of the responsibility of each, during his or her lifetime, to assure the future by preserving the past—has continued to bind successors to Fergus mac Roich and Senchán Torpéist, even to the twentieth century. "When Pearse summoned Cuchulain to his side, what stalked through the Post Office?" asked W. B. Yeats, whose poetic vision of modern Ireland etched ancient traditions on the events of 1913–1923. An image from the Táin , Oliver Sheppard's Death of Cuchulain , was the nation's answer. Today, guarding the entrance to the Dublin General Post Office, it commemorates not only the martyred leaders of 1916 but all of Ireland's champions, past, passing, and to come. Bound by their generational imperative, poets and historians continue to fuse future, past, and present as the years make and remake modern Ireland. Visible in the changing pattern—now prominent in the foreground,

now unnoticed in the background, by turns in and out of focus—is the figure of Douglas Hyde.

One bright, beautiful day in May 1968 in Frenchapark, county Roscommon—uncharacteristic weather for the small west-central Irish village nestled among hill and bog where rains fall generously in the spring of the year—a large official vehicle maneuvered confidently along narrow twisting roads and through crossroads, attracting the attention of pedestrians and bicyclists engaged in daily errands. Beyond the village center, on the road to Ballaghaderreen, it stopped at a churchyard nearly within sight of historic Rathcroghan, the plain pregnant with prehistoric monuments where legend has it that the Táin began. The familiar-looking stranger who stepped from the car was tall and thin, with the military manner befitting a man called "the Chief." Eamon de Valera had come to kneel at the grave of Douglas Hyde. With him were his grandchildren. Bob Connolly, the sexton, was the only other person present. After a few moments de Valera entered the empty church where the Reverend Arthur Hyde, Jr., rector of Frenchpark, had presided from 1867 to his death in 1905. In that church, as a boy, Douglas, fourth son of the Reverend Arthur Hyde (third to survive infancy), had listened unwillingly to his father's sermons, silently formulating conflicting opinions based on a broader vision of the world. There during his adolescent years he had obediently but reluctantly conducted Sunday school classes for children of the Big House landlords and local squirearchy who comprised his father's flock, and had assisted with other church duties. Manhood had taken him to Dublin, to London, to the Continent, and to North America, where his own ideas had flourished. Yet throughout his long life he had returned often to this same cemetery of the Church of Ireland in the parish of Tibohine in the village of Frenchpark to kneel at the graves of mother, father, daughter, brother-in-law, wife. Here, before Vatican II, in predominantly Catholic Ireland, with hundreds crowding near to bid him farewell and thousands more paying tribute along the route of the funeral procession from Dublin to Frenchpark, he himself had been buried in 1949.

Far more than an ecumenical gesture, de Valera's 1968 visit to the grave of Douglas Hyde was the personal tribute of a younger maker of modern Ireland to his mentor and predecessor; of one old friend, old comrade, to another; of modern Ireland's third uachtarán , or president, to its first. It was also an affirmation of the generational link forged by Senchán Torpéist centuries before, of the obligation each

Irish leader has to Ireland's past and future. Others had come the preceding day to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Gaelic League, the organization Hyde had helped to found and had led during a long and significant chapter of his life. Churchyard and church had echoed with familiar oratory. But this personal pilgrimage Eamon de Valera had chosen to make alone, with only his grandchildren to accompany him. He had not come to shout speeches to the crowd, calling out, "People of Ireland! People of Ireland!" with the note of urgency characteristic of his public addresses, but to whisper softly to the man who, like Fergus mac Roich, had made of himself a link in a great chain of national being, creating a commodious vicus of recirculation more accessible than that of James Joyce through which the old-new nation, modern Ireland, might be sustained.

Whispering at the grave of Douglas Hyde in the May sunshine of 1968, de Valera might have recalled the mission of the seventh-century poet to the grave of Fergus mac Roich. More likely his memories were of his own late-night visits to Áras an Uachtaráin when Hyde was president. The purpose of their nightly meetings had not been to reconstruct the past but to consider the present and develop strategies for the future. Hyde had been de Valera's personal choice for the presidency established under the Constitution of 1937. Few had understood why. Even after Hyde's unanimous election in 1938, newspapers and gossip mongers had talked of de Valera's "sop" to the Protestant Ascendancy, to the Gaelic revivalists, to the Trinity intellectuals, and to the Church of Ireland, as if ever in his political career this stern man had given weight to such considerations. No, de Valera had chosen Hyde for himself—for his experience, his judgment, and his political skills, honed over a period of nearly half a century; for his ability to move easily and smoothly in circles of which de Valera had never been part; for his shrewd understanding of Americans, Canadians, the British, the French, and the Germans at a crucial time in modern history when an independent Ireland was about to take its place on the world stage.

By 1938 de Valera, born in 1882, had been a schoolteacher, a mathematician, a soldier, a leader of the republican insurrectionists, and an architect of the Free State. His political strengths had been his determination, singleness of purpose, and endurance, his ability to inspire others to degrees of patience, fortitude, loyalty, and courage of which they might not have thought themselves capable. Hyde, born in 1860, had been a poet, a folklorist, a playwright, a philologist, a literary historian, a university professor, an antiquarian, a leader of the Gaelic Re-

vival, a pioneer of the Irish Literary Renaissance, and an Irish Free State senator. Cosmopolitan, politically sophisticated, and an easy conversationalist comfortable within a wide range of social contacts, during fifty years of public life he had proved adept at probing the thoughts and feelings of others while revealing little of himself, at signaling from offstage and providing onstage support to others who assumed major roles, and at concealing his own confrontational intentions behind a benign exterior. On the question of Ireland, the two men had long shared ideals and goals. De Valera was better understood, a strong and forceful leader whose life was like an arrow shot through the air. Hyde was an enigma, a man whose career, by 1938, had given rise to a myth, an internally inconsistent accretion of half-truth, misunderstanding, presumption, expectation, rumor, and opinion that until now has not been challenged by evidence. Clues to Hyde's motivation, goals, character, and personality lead through public and private records and personal memories to extraordinary conclusions. As in all good detective stories, investigation must begin with a review of documented and objective facts, with the public scaffolding of the private life.

2

A Smiling Public Man

Douglas Hyde had lived a long and controversial life when, at the age of seventy-eight, he was unanimously elected first president of modern Ireland. His seven-year term (1938–1945) coincided with that crucial period in modern history when the war that swept Europe and Asia and buffeted the Americas not only threatened Ireland's very existence but compounded the social, economic, political, and cultural pressures already at work in the self-proclaimed new nation.

Born in Castlerea, a market town in county Roscommon seven miles west of the village of Frenchpark where he now lies buried, Hyde spent the first six years of his life approximately thirty miles to the north in the modest glebe house of Kilmactranny, where his father was rector until 1867. Although still remote by modern standards, the county Sligo village already had won the small place in Irish history that later fascinated Hyde, for it was here in the early eighteenth century that Donnacha Liath (Denis O'Conor), although impoverished during the wholesale confiscations of 1692–1700, had maintained his position as descendant of Connacht kings and Irish high kings. In O'Conor's modest cottage Blind O'Carolan had played on his celebrated harp the musical compositions for which he was known throughout Europe. This same cottage, a refuge for hedge schoolmasters and unregistered priests during Penal times, often had sheltered O'Conor's banished brother-in-law, the daring Bishop O'Rourke, who traveled the country disguised as "Mr. Fitzgerald" under the nose of English soldiers.

"The Hill," the handsome Georgian mansion in Castlerea where

Douglas Hyde was born (since altered by later owners), was not his own family home but the glebe house of Kilkeevan parish, home of his maternal grandparents, the Venerable John Orson Oldfield, archdeacon of Elphin and vicar of Kilkeevan, and Maria Meade Oldfield, daughter of Frank Meade, Q.C., of Dublin. Elevated by the hill that gave the house its name, in 1860 it looked across Main Street and over the walls and gardens of the Sandford demesne, now Castlerea town park, on the banks of the river Suck. A few hundred yards along the same street was the more modest birthplace of Sir William Wilde, a distinguished eye surgeon and antiquarian, son of the town doctor and father of Oscar Wilde. Although Oscar himself was born in Dublin in 1854, long after his father had left Castlerea, local memory continued to associate the house with the Wilde family. Prevalent in Hyde's boyhood were rumors, persistent even today, of a mysterious message scratched on a back window. When its street-level rooms were converted to a pub, the name given it was the Oscar Bar. At the time of Hyde's birth historic Clonalis—the walled estate at the edge of town on the Castlebar road that is still held by the O'Conors of Connacht—was the home of Charles Owen O'Conor Don, M.P., great-great-great-grandson of Donnacha Liath of Kilmactranny. Preserved and expanded by O'Conor Don, its extensive library and manuscript archive reflected then as today the interests of Donnacha Liath's son and grandson, Charles O'Conor ("the Historian") of Bellangare and Dr. Charles O'Conor, scholar, translator, and librarian to the Duke of Buckingham at Stowe. Distinguished visitors included not only well-known political figures but scholars from England and abroad. As a young man invited to visit the forty-four-room mansion with its halls and dining room lined with portraits of O'Conor ancestors, Hyde had examined there such ancient Gaelic manuscripts as the fourteenth-century Book of the Magauran (now in the National Library) and the earliest known fragment of Brehon law. At Clonalis also he had stood wondering before the harp that O'Carolan had played in Kilmactranny.

Hyde's paternal grandfather was the Reverend Arthur Hyde, Sr., vicar of Mohill, a town near Drumsna, where Anthony Trollope, then a post office inspector, had found the germ of his first novel, The Macdermots of Ballycloran . As a lineal descendant of Sir Arthur Hyde, whose reward for service to Elizabeth I had been a knighthood and letters patent to 11,766 acres of county Cork, he belonged, however—through a junior line—to the Cork Hydes of Castle Hyde, a celebrated estate on the Blackwater that had remained the family seat until 1851. Father,

grandfather, and great-grandfather before him had served the Church of Ireland since the seventeenth century. Regarded before disestablishment as more social and economic than religious in nature, the respectable career the church provided—as Lady Melbourne had advised her son William—was particularly suited to younger sons. Indeed, had William's elder brother not died, clearing the way for him to become Lord Melbourne, he would have had neither the means nor the social position to rise as he did to prime minister and so earn his place in English political history.

No providential death having intervened to raise the eighteenth-century family of Douglas Hyde from junior-branch status, son followed father: the heir of the Reverend Arthur Hyde of Hyde Park, county Cork, became the Reverend Arthur Hyde, vicar of Killarney. His marriage to a daughter of George French of Innfield established a connection with the Frenches, the family of Lord de Freyne, proprietary landlord of Frenchpark. So it was that in 1867, when he was appointed rector of the parish of Tibohine, the Reverend Arthur Hyde, Jr., son of the Reverend Arthur Hyde of Mohill and father of Douglas Hyde, moved his family to Frenchpark, to live among country squires and landed gentry in a social environment more favorable than that offered by Kilmactranny. Neighboring kinsmen in Frenchpark included not only Lord de Freyne but his brother, John French, whose Roscommon estate, Ratra, was later to become, in 1893, the home of Dr. Douglas Hyde.

Such a pedigree was not the kind from which controversy ordinarily might be expected, nor was there anything apparent in Hyde's childhood or youth that pointed to the many and various careers that were later to engage him. When he grew old enough to handle fishing rod and gun, he was included in the sporting activities his father organized with his sons. But as Douglas's two brothers, Arthur and Oldfield, were in general too old to be his companions and his sister, Annette, who was five years his junior, was too young, most of Hyde's days were spent alone with his dog, Diver, or tagging along behind amiable workmen, or with the sons of neighboring cottagers from the glebe lands and nearby estates. Crossing meadow and bog on these daily rambles, he often stopped for a cup of tea and a biscuit in the thatched cabins that dotted the countryside. His welcome was warmest in those in which Irish was the primary language, where it was a matter of some amusement that the master's boy had an ear for the language and liked to try his few phrases on willing listeners. Douglas's interest in Irish won at-

tention at home, too, where until he and his brothers were old enough to assert different aspirations both the Reverend and Mrs. Hyde assumed that all three of their sons would follow the family tradition and enter the ministry. The church, advised the Reverend Hyde, when young Arthur and Oldfield mocked Douglas for making a serious study of what they considered a language of servants, was particularly interested in young men who might qualify for a living in one of the areas to the west where Irish was still dominant. But Douglas—who was educated at home, as were his brothers and sister, in his father's well-stocked library—also was given to understand that history, natural science, mathematics, the classics, and Continental languages and literature were more important subjects, in which one day he would be required to pass entrance examinations for admission to Trinity College.

Before his sixteenth birthday Douglas had acquired the informal elementary education in the Irish language and Irish history and the interest in Irish folktale and song which he then began to pursue through self-directed study of texts bought in secondhand bookstores on rare boyhood trips to Dublin. It was in a Dublin bookstore when he was not yet eighteen that he first met members of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language, an organization of which O'Conor Don of Clonalis was a founding member and officer. Through the society he was introduced to the old manuscripts and rare books of the Irish-language collection of the Royal Irish Academy and to new friends who encouraged his attempts at translating and writing original verse in modern Irish. Before he was twenty-one his Irish poems and translations had appeared in periodicals published on either side of the Atlantic, and he had been accepted as a cultural nationalist by fellow members of both the sedate and literary society and its splinter organization, the more activist Gaelic Union.

Meanwhile there was Trinity to be concerned about. Admitted in 1880 to the divinity program through which, from the sixteenth century, sons of the Ascendancy (including his own father and grandfathers) had received their university education, Hyde quickly won a reputation as an outstanding scholar. To his father it seemed that for Douglas a career in the church and a living in Irish-speaking Mayo was assured. Hyde himself was ambivalent, especially when he discovered that Trinity circles equated an interest in modern Irish with nationalism and regarded nationalists as anathema. Despite the disapproval of influential faculty, he not only continued his membership in the society and the Gaelic Union but joined the beautiful and radical Maud Gonne,

the flamboyant young Yeats, and other women and men of their age and class in a circle called "the Young Irelanders" (after the revolutionary Young Ireland movement of the 1840s) that clustered around John O'Leary, an old Fenian leader returned from exile. Yet to most people Hyde seemed harmless enough, for between 1886 and 1890, having earned B.A., M.A., and LL.D. degrees, he appeared intent on becoming nothing more dangerous than a Dublin man-about-town: a gentleman scholar who spent his days in the library of the Royal Irish Academy and his evenings at theaters, concerts, and dinner parties; a convivial member of proper clubs; a familiar and socially adept figure at teas and tennis parties who talked easily about his travels to English watering holes and the fashionable and scenic gathering spots he had visited on the Continent; an aspiring candidate for a respectable university post in literature and language.

This appearance of indolence and indifference was misleading. By the time Hyde was thirty, his scholarly publications (at which he had been working in fact very seriously) were attracting as much attention as his published poems and translations; his growing international reputation as an authority on Irish folklore and as a theorist and methodologist in the new field of folklore scholarship was bringing him respectful inquiries and requests for assistance from eminent scholars abroad. Had he not been opposed (because he advocated educational support for modern Irish) by such powerful political academicians as John Pentland Mahaffy, later provost of Trinity College, he might have had the Irish university post he coveted. But on this issue Hyde was as implacable as his enemies. Alternatives were few until an invitation to Canada to serve a one-year term as interim professor of modern languages at the University of New Brunswick offered an opportunity beyond Mahaffy's sphere of influence.

In Fredericton, where life was both pleasant and comfortable, Hyde soon began to weigh the possibility of emigrating permanently to Canada or the United States. His duties, which he enjoyed, included teaching French and German; he quickly acquired a circle of congenial friends; he became fascinated with the language and culture of nearby native American tribes; and he set for himself such compatible scholarly tasks as that of comparing native American folklore with the folklore of Gaelic Ireland. Yet at the same time, in what seemed a strange departure to acquaintances who knew of such activities, he sought contacts with such men as O'Donovan Rossa and Patrick Ford, known Fenians and Irish compatriots who were unwelcome in Ireland because of their

political activities. And in his diaries and in notes that he sent home he attempted to gauge Irish-American reactions to contemporary events in Lord Salisbury's England and Parnell's Ireland. Although Hyde's letters from Canada cite his father's illness as the deciding factor in his return home at the end of his New Brunswick year, they also reflect his strong support of Charles Stewart Parnell and his interest in the trials and scandals that had weakened Parnell's position and divided public opinion on the question of his reelection.

By October 1891 Parnell was dead, and with him the energy, excitement, and hope he had generated. The Parnellite nationalists were in rout; the entire Home Rule party was in disarray; the populace was too discouraged to respond to political attempts to rally them. Back in Ireland, Hyde had returned to his usual circles, where his reputation was enhanced by the success of Beside the Fire, published in 1890 and the first of his books to establish his work as an important source for the young writers of what was soon being called "the Irish Literary Renaissance." Word from abroad was that his poems and translations, reprinted in Paris and Rennes, were being enthusiastically received on the Continent, especially in Paris and Brittany where Celtic studies had become a growing area of scholarly investigation and a pan-Celtic movement was gathering popular strength. He was receiving letters soliciting his new work from both popular and scholarly publications.

Elected president of the newly organized National Literary Society in 1892, Hyde boldly chose as both title and theme of his inaugural speech "The Necessity for De-Anglicizing Ireland." Its call for cultural revolution raised few alarms among English authorities, apparently because they could not conceive of an effete literary circle that was seditious, or of folktales, folk songs, and traditional games that could pose a clear and present danger to the state. Nor did the government take notice a year later, in 1893, when Hyde was chosen first president of another new organization, the Gaelic League. Officially its policy was to avoid conflict with the British government by steadfastly maintaining a nonpolitical stance. Unofficially it engaged in activities expressly designed and publicly proclaimed to have as their purpose the fulfillment of the goals Hyde had set forth in his speech on deanglicization. But the prime reason why Hyde's tentative plans for a return to Canada were dropped was that his friendship with Lucy Cometina Kurtz, an attractive, intelligent, and intellectually independent young heiress to whom he had been introduced by his Oldfield aunts, had ripened into engage-

ment. By 1893 they were married. As the turn of the century and his fortieth birthday approached, Hyde's professional and private life were by all appearances both promising and satisfying.

During the next twelve years Hyde continued composing, collecting, and translating the Irish stories and poems that provided, according to Yeats, the "entire imaginative tradition" that stirred the writers of the Irish literary revival. His scholarly studies—expanded to include philology and literary history—drew inquiries from such eminent academicians as Harvard's Fred Norris Robinson and Georges Dottin of the University of Rennes. His circle of friends grew to include the distinguished German Celticist, Kuno Meyer. By 1899 Hyde had published A Literary History of Ireland, a full-length pioneer study still regarded as authoritative. Persuaded by Lady Gregory and W. B. Yeats to join their newly formed Irish Literary Theatre, forerunner of Dublin's famous Abbey, he successfully tried his hand at writing original plays in Irish for its repertoire. By 1905 he had composed a corpus of Irish plays performed throughout the country and available in print, and he had preserved hundreds of poems and stories from the oral tradition in such collections as Beside the Fire (1890), Love Songs of Connacht (1893), The Three Sorrows of Storytelling (1895), and Songs Ascribed to Raftery (1903). Extracts of his work that appeared in translation in France and in English-language periodicals in the United States and Ireland had attracted enthusiastic readers who, writing to editors, were requesting more. So varied and prolific were Hyde's activities in the years between 1893 and 1905 that Yeats publicly compared him to Frederic Mistral, the Provençal poet and founder of the Félibrige who won the Nobel Prize in literature in 1904.

During these years the Gaelic League, still led by Hyde, also was gathering strength, abroad as well as in Ireland, and political and revolutionary pressures for Home Rule were increasing. Despite the clearly political implications of many of his activities, Hyde continued to maintain a nonpolitical stance and to insist that his own and the league's efforts were confined within a purely cultural framework. In 1899, with testimony from eminent scholars from abroad to support him, he defeated the governors of the British education system in Ireland on the question of the validity of formal study of the Irish language. In 1900 he took on the British Post Office in an epic battle that ended in a Pyrrhic victory for Goliath, so numerous were those who came to the aid of David. Word of these successes traveled, winning new supporters

for Hyde and the Gaelic League not only in Ireland but also in England, on the Continent, in Canada, the United States, Mexico, Argentina, and even in the Phillipines and far-off Australia.

As through branches and affiliate organizations the influence of the league spread, Hyde's personal popularity increased correspondingly. In persuasive letters urging Hyde to present a series of lectures in the United States, John Quinn of New York, a wealthy Irish-American philanthropist and lawyer, declared that academic and community groups in fifty-two American cities were eager to sponsor an eight-month tour, if he would but agree. Among prominent Americans who showered Hyde with invitations in 1905–1906, as he crossed and recrossed the United States and Canada by rail, carriage, and boat, were the presidents of Harvard, Yale, Catholic University, the University of Wisconsin, and the University of California; the daughters of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow; Andrew Carnegie; Finley Peter Dunne (Chicago's famous "Mr. Dooley"); and President Theodore Roosevelt. All San Francisco seemed to embrace him: its citizens responded generously to his request for financial contributions to continue the league's efforts on behalf of Irish culture and the Irish language.

The year before his fiftieth birthday Douglas Hyde began a new career as professor of modern Irish at University College, Dublin. Among his students were women and men who later taught Irish in this and other Irish universities. Some were appointed to the distinguished faculty of the Dublin Institute of Advanced Studies. Two months after Hyde's fifty-sixth birthday a small host of brilliant young men whom he had inspired and taught went to their deaths in the Easter Rising of 1916. He had opposed their action not, as is often stated, because he was against physical force as a means of gaining national independence but because he feared that their brave vulnerability would result in just such a blood sacrifice at a time when he believed that all alternatives had not yet been exhausted. Armistice in 1918 provided relief for neither Douglas Hyde nor Ireland. Physically ill, emotionally depressed, and beset by personal and family troubles and tragedies, he struggled to regain his equilibrium as Ireland struggled through the war of independence (1918–1921) and the civil war (1921–1923) that hampered efforts to build the limited self-government permitted under the divisive Treaty of 1921. Called upon to serve in the Free State Senate in 1925, Hyde readily assented, hoping to find relief from the sorrows of his personal life in renewed political activity and his continu-

ing commitment to scholarship, writing, and teaching. What he found instead was a factionalism that forced him to expend most of his energies on defending himself from personal attack in a climate in which old alliances were often abandoned and new ones were quickly repudiated. At the end of his senate term Hyde nevertheless made a bid for reelection—and lost.

During the next seven years, at an age when most men contemplate retirement, Hyde continued to devote long hours of every day to his teaching and scholarship and to Lia Fáil, a new literary journal in Irish studies that he had launched. Meanwhile anti-Treaty republicans who had been boycotting the Free State government reentered politics with the purpose of winning by election what they had been unable to gain by guerrilla warfare. Eamon de Valera, American-born survivor of the Easter rebellion, war of independence, and civil war, a committed nationalist who had been one of Hyde's young Gaelic Leaguers, soon emerged as the dominant political leader. His success was greeted by some as a sign of a new political optimism. To many dispirited citizens of the Free State it seemed that Thomas Davis's promise of a nation once again might yet be fulfilled. On de Valera's agenda was the writing of a new Constitution that would eliminate the provisions of the treaty he had opposed and establish the framework of the republic he had long envisioned.

In 1937 de Valera persuaded Hyde—then seventy-seven, retired from the university, but still actively engaged in scholarship at home in Roscommon—to return to Dublin to serve a second term in the Free State Senate. On December 29, 1937, the new Constitution was ratified. In the spring of 1938, at de Valera's insistence, Hyde agreed to stand for the office of uachtarán, or president, that had been created by the new Constitution. The same document silently abolished the Irish Free State, establishing by fiat the independent modern Irish nation called Ireland, or Éire. In May all political factions united to elect Douglas Hyde first president of an independent Ireland. For himself de Valera had reserved the post of taoiseach, or prime minister.

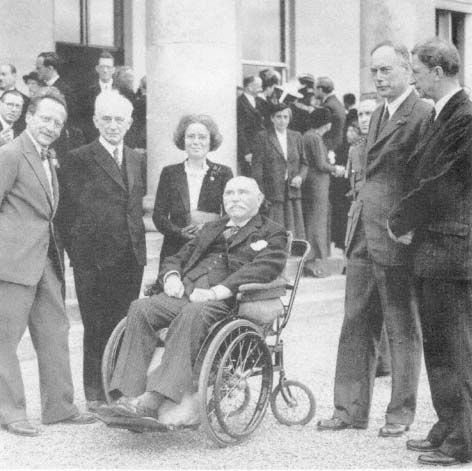

Seven years later, in 1945, at the end of a first full presidential term that had spanned the difficult war years, Hyde was asked if he would stand for a second term. He was eighty-five years old and he had suffered a stroke that had left him unable to walk, but his mind was as young and curious, his wit as active, and his commitment to the Irish nation as firm as ever. Nevertheless, he declined: the character of the office of president had been shaped under his aegis; it was time, he

believed, for someone else to take a hand in its future development. This time, however, instead of returning to his native Roscommon, he wanted to remain in Dublin, characteristically close to the action. "Little Ratra," a home in Phoenix Park near Áras an Uachtaráin, was made available to him. There he died, modern Ireland's first elder statesman.

Energetic, amiable, eminently approachable, an easy conversationalist and a charismatic speaker in several languages, Hyde was the kind of man whom people liked to refer to by nickname. In the Big House milieu in which he had been brought up, he was "Dougie." To the millions who knew him best through his work on behalf of the Irish language, he was "An Craoibhin," (from An Craoibhín Aoibhinn, "the delightful little branch," an Irish pen name he had adopted as a young poet). His sister, Annette, called him "Humpy," a name she had given him in childhood, when to her it seemed that whenever she wanted his company outdoors, he was bent over book or notebook. To his daughters he was their affectionate, prank-loving "Tweet." Yet he was also, contemporaries avow, an enigmatic figure, a strange and complex man with a private self kept well hidden from others and a goal-oriented capacity for callousness and thoughtlessness that shocked his most intimate co-workers whenever it emerged. Remembered by the people of northwest Roscommon as among the kindest and friendliest of the local gentry, he was also capable, they admitted, of a petty stinginess. In social circles he was regarded as a devoted husband and father, yet to this day private recollections and rumors of both serious and short-term romantic attachments persistently circulate. Widely perceived as a man dedicated to a cause, he was a puzzle to many who openly wondered at a commitment that, given his class, birth, and social status, cost him so much and held so little personal promise. On occasion his emotional involvement became so intense as to lead him to betray a friend. At the same time he was amused rather than annoyed by associations drawn between his name and that of the protagonist of Robert Louis Stevenson's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde . After his death conflicting statements by others concerning the date and place of his birth raised questions about his parentage. Unchecked by formal investigation and published evidence, over the years anecdote, rumor, recollection, and opinion have been quoted as fact.

Known thus to everyone and no one, Douglas Hyde, a maker of modern Ireland, died in 1949, leaving behind him no easy explanations of his life story but diaries, letters, copybooks, and journals, written

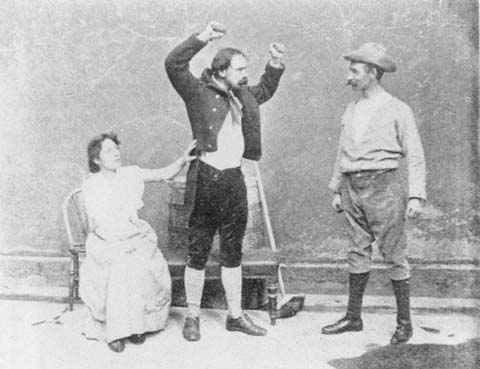

mostly in Irish but also in English, French, German, and occasionally Latin and Greek, to be sifted and winnowed in search of truths. His published writings include not only his own work, translated and published in many different countries, but his collaborations with Lady Gregory and W. B. Yeats. Among hundreds of correspondents from all over the world whose letters he answered, usually within twenty-four hours of receipt, were such disparate figures as Theodore Roosevelt, president of the United States; Katharine Tynan, distinguished poet; and Eoin O'Cahill, a native Irishman who had left Ireland as a young man but who returned to it in spirit at the end of his life when, living in Michigan, he refashioned figures from Irish mythology to create stories in Irish of the American Wild West. Hyde touched the lives of thousands; hundreds preserved recollections of specific incidents that reveal aspects of his character and personality. His wide circle of close friends was as varied as the range of his correspondents. To the end of his days it included Maud Gonne, whom he had once tried to teach Irish; Sinéad de Valera, who had played the Fairy to his Tinker in his play The Tinker and the Fairy ; the O'Conors of Clonalis in Castlerea; An Seabhac (Pádraig Ó Siochfhradha), folklorist of Dingle; Thomas Lavin, a former Frenchpark neighbor and a contemporary, father of the Irish writer Mary Lavin; old comrades from the Gaelic League; and the Mahons and Morrisroes of the cottages just outside the gates of Ratra, the home two miles from the center of the village of Frenchpark in county Roscommon that had been purchased for him from the estate of John French by the Gaelic League.

Today an afternoon's ramble that takes as its starting point the remains of the foundation of the now ruined Ratra passes over nearby meadow, along bog roads, through farmyards, and by stone cabins, many also in ruins, where 128 years ago a clergyman's son learned his first Irish words and the transformation from Douglas Hyde to An Craoibhin and an t-uachtarán began. Not far from the cottages outside the gates, in which there are still Mahons and Morrisroes who remember Douglas Hyde, is the cemetery in which he lies buried, next to the church in which the Reverend Hyde served as rector from 1867 to 1905.

Behind these public facts there was a private life.

3

The Budding Branch

February 28, 1940, was brisk and cold. A chill wind swept through Phoenix Park, rattling the great windows of its three stately homes, former residences of British government officials. From the chimneys of Áras an Uachtaráin, official residence since 1938 of the president of Ireland, smoke from turf fires rose and quickly dispersed, its unmistakable scent evoking warm recollections of distant cottages in hearty Dubliners walking or cycling nearby. During the hard winter months past, to relieve distress caused by wartime shortages, the president had ordered that the mansion's coal stores be distributed among the people of Dublin. A turf fire was in any case what he himself preferred, nor did he mind giving up dusty bins of shiny black coal for the velvet-brown stacks from midland bogs that he now had the pleasure of seeing when he took an occasional turn outdoors, striding along purposefully or stopping to banter with a workman, his long woolen muffler and the smoke from his pipe both curling around and behind the collar of his tweed jacket.

Built as an eighteenth-century ranger's lodge, Áras an Uachtaráin had been enlarged in 1816 to create a proper viceregal residence for the British lords lieutenant who then governed Ireland. It was at that time that the wings and portico that give the mansion its neoclassical appearance had been added. hastily and not yet completely renovated in 1938 to serve as the home of the first Irish president, it needed just such touches as a turf fire, in its new occupant's opinion, to give it a proper Irish flavor. Similar patriotic sentiments, he sometimes ex-

plained to visitors, his eyes wide and shining with feigned innocence, led him to keep a small flask of poteen in the presidential study. Michael McDunphy, secretary to the president, frankly disapproved of the poteen—and had not been so sure of the turf. An efficient, conscientious, and serious man favored by de Valera for the newly established government position to which he had been appointed even before Hyde's election, McDunphy worked hard at the job of hiring and heading the presidential staff, assuring its efficient operation, establishing protocol, maintaining liaison between Áras an Uachtaráin and other branches of the government, and communicating through diplomatic channels and the media with the world at large. Stacking turf outside the presidential mansion was just one of many things he had to be concerned about, for fear of what the newspapers might make of it. McDunphy was right, of course—from previous experience Hyde knew that political cartoonists, like cats, should never be overfed—but in this case wartime exigencies allowed the president to have his turf and the people of Dublin to have their coal, yet left the caricaturists, good hunting cats all, still lean and hungry.

Caricaturists and cats both figure in Irish history—probably because, as a monk with an ironic bent observed some eleven centuries ago, they employ similar skills:

I and Pangur Ban my cat,

'Tis a like task we are at:

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.

The original of that old Irish poem—found in Austria, in the margins of a manuscript of a codex of St. Paul—was well known to Hyde. As a young man he had made oblique and playful allusion to it in a mock lament he had written in modern Irish, about the loss of a kitten, companion of his study, on which a portly friend had sat. Himself a Gaelic scholar, translator, and poet, Hyde admired the way in which Robin Flower had hunted and caught the flavor of the poem in a singsong English different from Kuno Meyer's earlier and more literal verse translation. The German Celticist, an old friend, had struck a nice balance beween scholarly integrity and poetic sensibility, but Flower's greater concern for the spirit of the original was more consistent with Hyde's own translation ethic.

Better far than praise of men

'Tis to sit with book and pen;

Pangur bears me no ill will,

He too plies his simple skill.

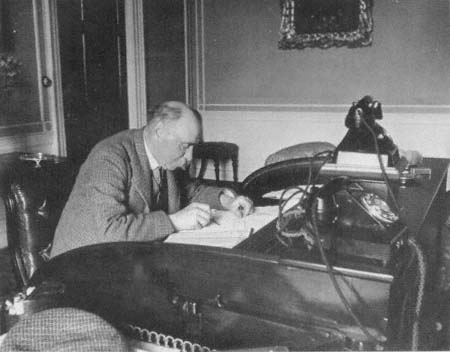

On this February day in 1940, that was Hyde's task: to ply his simple skill with words. Warmed by the turf fire in his study, he sat at his writing desk, his sturdy figure hunched over three sheets of blue four-by-six-inch notepaper, his rounded back to the door.

'Tis a merry thing to see

At our tasks how glad are we,

When at home we sit and find

Entertainment to our mind.

Less able to find time to entertain his imagination since taking office as president, Hyde delighted in opportunities such as the one before him that combined duty with pleasure. His task was to make a rough draft of what he planned to say to an audience of schoolchildren on the subject of studying Irish.

Oftentimes a mouse will stray

In the hero Pangur's way;

Oftentimes my keen thought set

Takes a meaning in its net.

Seeking meanings that he might catch in his nets, Hyde looked up from his work to glance through French windows, past formal gardens, at the high, white sky beyond. It was an old habit of his, resting his eyes on the sky while he was thinking, learned when he was a boy of twelve or thirteen and had begun to have the soreness of his eyelids that had plagued him off and on ever since. A nuisance, that soreness of the eyes. Fortunately it had never completely disabled him, nor had he ever let it interfere seriously with either his reading or his writing, not even at home in Roscommon, where it always seemed worse. If some days through habit he found himself looking up at the sky more often than usual, it was not always to rest his eyes but to search for—what?

'Gainst the wall he sets his eye

Full and fierce and sharp and sly;

'Gainst the wall of knowledge I

All my little wisdom try.

In his presidential study in Aras an Uachtaráin, whenever his glance strayed first round the room and then through the French windows to

the sky above the garden, the sky was full of wheeling gulls. A great country for birds, Ireland. Even in the center of the city, in the reading rooms of the National Library, they could be heard scuffling on the roof and screaming overhead. In Roscommon, in that same sky continually covered and uncovered by scudding gray clouds, a teal might be dropping back to the sheltered ledge bordering the lake near Caoile from which the entire flock had arisen, moments before, at the sound of a hunter's first shot. At Ratra, if the turlough in the far field were larger today, a lapwing reflected in its shallow waters would be an easier target. If not, for the hunter's gun there were always the omnipresent crows silhouetted in the leafless trees of late winter.

Though miles away in Dublin, any Roscommon man would know from the look of the sky how the air smelled west of the Shannon, how the wind felt on a reddened cheek. Days toward the end of February often were fine there: brisk and cold, with perhaps a light dusting of new snow to limn the prints of a saucy hare after a week's thaw. In the early, frosty morning on just such a day as this when he was a boy Hyde used to walk down to Cloigionín-a-naosc's in snow that squeaked underfoot; flush a snipe at the flash; return home slowly, sometimes stepping in his own earlier footprints, grown large since he had left them. On such a day, as a boy, he often went out again after supper, sending Diver to retrieve a jackdaw shot close by the house or running along well-worn paths, the dog at his heels, to enjoy for a while in the lengthening twilight the comfort of Seamas Hart's turf fire and the warmth of his companionship.

Such thoughts of the past inevitably crowd out the present when a writer faces the kid of task Hyde had before him on that last Wednesday in February at the start of his eighty-first year, a winter's day with a promise of spring in the air. To think what would draw a response from children requires remembering what it is like to be a child.

When a mouse darts from its den

O how glad is Pangur then!

O what gladness do I prove

When I solve the doubts I love!

Hyde wrote and crossed out and wrote again. Sixty-five, seventy years had passed since he was a boy. Curious turns and twists of fate separate youth and age. A memory that would bridge the distance between himself and the children he soon would meet, that was what he needed: something that would persuade them that near the end of the journey

of life the old must look to the young for assurance of that continuity of effort that is their last earthly reward. Would the children respond to such a memory? How would they regard him? Would they listen to what he had to say? Or would they squirm, suppressing giggles and yawns, wishing the event over, the old man gone? If Hyde could have met each youngster separately, coaxed from the eyes of each the mirror of his own, surely they would have become friends. Protocol, however, required that the president of Ireland address schoolchildren in groups.

Hyde always had had an easy rapport with children. Summers in Roscommon in the years before his wife became ill, while she chatted with other ladies in the drawing room at Clonalis, he used to play hide-and-seek with the six O'Conor girls, up and down stairs, behind chairs, under beds, and through the forty-odd rooms of the "new" house (so-called to distinguish it from the old one, down by the river, abandoned in 1872 after the first wife of Charles Owen O'Conor Don died there of the tuberculosis that also had killed his mother). Hyde liked visiting Clonalis with Lucy, even when none of the O'Conor men was about, not only for enjoyment of the children but for the pleasure of past associations. Castlerea was a familiar seven-mile drive from Frenchpark village; it was just nine miles from Ratra, the old John French estate forever associated with Seamas Hart where he expected that one day he would end his days. The road through the top of the town passed the nine-hole Clonalis golf course where he still sometimes played when he was home, then curved along high stone walls past the great iron gates of the estate on its way to Castlebar. When he and Lucy had business to transact in Castlerea they would turn left onto Main Street before reaching Clonalis, cross the bridge over the river Suck, and pass the post office on the left, to the market square. The road entering from the right a few yards beyond ran down to the railroad station. On one side of this road, at the junction of Main Street, was Kilkeevan Church, where he had been baptized; on the other was the Hill, then the glebe house of Kilkeevan parish, home of his grandparents, where he had been born. His grandfather Oldfield had died later that year. Sometime after, his grandmother and unmarried aunts, Maria and Cecily, had moved to Blackrock, in county Dublin. In addition to Maria, Cecily, and his own mother (her name was Elizabeth, but everyone called her Bessie), the Oldfield daughters included Ann, wife of Dr. William Cuppaidge, the physician who was always called to treat his chronic soreness of the eyes and other family ailments.

Charles Owen O'Conor Don, whose first wife had died at Clonalis,

had known the Oldfield family. He had been a young man serving his third year in Parliament when Douglas Hyde was born. The O'Conors also had known the Wildes, Oscar Wilde's father and grandfather. Sir William, who had received his early education at the Elphin Diocesan School, had left Roscommon for Dublin long before Oscar was born, so Oscar and Douglas had not been acquainted as children. George Moore, however, who had grown up at Moore Hall near Partry in Mayo, used to tell of summertime boating and picnicking, himself and his brother Maurice, with the Wilde boys, Oscar and Willie, on Lough Carra. As a young man Hyde had been fascinated by stories of the boys' mother, Lady Wilde, who called herself "Speranza" and who had written poetry for the Nation .

February 28, 1940: more than seventy-nine years had elapsed since the Venerable John Orson Oldfield had been laid to rest behind the iron gates of the overgrown Church of Ireland cemetery on Castlerea's Main Street, across from Kilkeevan Church; almost thirty-six since Charles Owen O'Conor Don had taken his place in the family plot of the Roman Catholic cemetery adjacent to Clonalis, his ancient title passing to first one nephew and then another. Oscar Wilde had died in 1900. George Moore was dead, too; it was seven years since his ashes had been buried on an island in his silver-green lake. Where were the O'Conor girls on this crisp winter morning? Married, some of them—Jo working in London for the British Foreign Office. On a postscript to a letter, Hyde had written that he could not send her his love as long as she held that job.

But on this February day Hyde had no time to reflect either on the curious convergence of personalities associated with Castlerea or on the whereabouts of the six O'Conor sisters. The work at hand had nothing to do with Frenchpark or Castlerea or any other part of his native county. The children for whom he was planning his brief talk were not those he had known as Roscommon neighbors and friends. Who was he to these young citizens of a new and different Ireland? A symbol—their first constitutional president? How old he must seem to them, how distant his memories of the past. Would they understand that once upon a time an t-uachtarán had been a child like each of them? Could he talk to them perhaps not as their president but as An Craoibhin Aoibhinn, the poet, playwright, and folklorist whose work they had read or recited? If he had taught their parents or teachers, some might have heard of him as the Dr. Hyde who had been professor of modern Irish at University College. He was often photographed for the newspapers,

greeting visiting scholars and other dignitaries from abroad. But what do children care about scholars and dignitaries? What do they care about? Wars, heroes, history? What had he cared about when he was a boy?

Against the high, white sky over Phoenix Park there rose in the mind of Douglas Hyde the image of a small boy, not more than ten years of age, who had been taken from his native Connacht bog and mountain across the troubled Irish Sea to England. A crowd of other boys surrounded him, mocking him because (the written words leaned forward as Hyde wrote, straining to outdistance his pen as they raced uphill across the page) "nach raibh mé cosamhail leo féin" (I was not like them). One boy—Hyde recalled wryly that he was "in the same situation as myself" (that is, another Irish boy in England)—led the attack, calling Hyde an "Irish Paddy." Hyde wrote out the scene in Irish, that he might reconstruct it for the children he was to address: "Never say that again," he had threatened the boy, raising his fists. "You're nothing but a lazy loafer; I can beat you any day. I speak your language as well as you, and can you say a single word of mine? You had better realize that I'm twice the man—the double and better of yourself. And you, you grinning half-brain, you make fun of me and call me names."

"I was young then, and hot-tempered." Hunched over as Annette always remembered him, Hyde continued his recollection, contracting the size of his letters in his haste to finish before his remembered emotions cooled, excusing the fury of the embattled child he had been as he became again the elderly president of Ireland. But a blaze is not easily extinguished, even after seventy years, especially when it has been kindled by thoughts of injustice; firm and clear were the letters of the words with which he ended his account: "I still think I was right."

He had it then, three full sheets of notes and phrases from which to develop what he would say to the children.

So in peace our tasks we ply,

Pangur Ban, my cat and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.

All he needed to finish his task were a few final words in Irish to encourage the children to continue their study of the national language.

Each of you, every boy or girl among you . . . you can say as courageously and truly as I did that you are the better person, twice over! But you can't say it without your own language, so don't lose a bit of your Irish, because if you

do it is history that you lose. Speak Irish among yourselves, for fear of losing it. And don't be timid—it won't be long before Irish spreads all over the world.

As he worked the little drama into his speech, for a short while Hyde was no longer, as he sometimes complained, a bird in a gilded cage. He had rummaged through memories of his childhood to find his characters; he had turned the clock back to set them moving and talking. He was a guest again at Coole Park, working on the script of a new play that he would read out to Lady Gregory and Yeats after dinner. At Coole, when he finished the scene he was working on, he used to walk down to the lake to watch the swans before dinner. At Áras an Uachtaráin, he might take a turn around the house to enjoy the turfragrant air.

Practice every day has made

Pangur perfect in his trade;

I get wisdom day and night

Turning darkness into light.

Had such an event as Hyde described occurred when he was ten? Did it take place in England? Were the circumstances as he related them? In the diary of his eighteenth year he had recorded in retrospect a few facts about his brief and only school experience, apparently the kernel of his story. It had taken place when he was thirteen: "My brother Arthur went to college in the year 1871 and my other brother Oldfield did the same in 1875. I stayed all the time safe at home except in 1873 I hurt my left thigh." The leg injury had set him back in his studies. He was sent in consequence to a "thieving school in Dublin" where he remained about three weeks and "learned nothing." Dissatisfied with the quality of the school, his father soon had withdrawn him.

Hyde's later accounts of this experience, separately retold by his daughter, Una Hyde Sealy, and his first biographer, Diarmid Coffey, suggest other reasons for his withdrawal: on the one hand, a case of measles; on the other, the Reverend Arthur Hyde's unwillingness to shoulder the cost of Douglas's tuition. Between these two sources there are discrepancies also in just how long Douglas remained at the school before he was taken home. The school is not named, but Una Sealy was sure that it was in Kingstown, now Dún Laoghaire, a suburb south of Dublin, rather than in Dublin proper. Coffey agreed, adding that only the shortness of Hyde's enrollment "prevented his becoming as Anglicised as most Dublin schoolboys," for such Irish schools, catering as they did to upper-class families, were modeled on English boys'

schools. Recreating the experience in 1940, Hyde seems to have mirrored reality not as it was but as it might have been. Creating a scene reminiscent of The Lord of the Flies, he increased the tension between boy and setting by repositioning his remembered self in England rather than Dublin, then enhanced the potential for conflict by providing his boyhood persona with the verbal ability to defend a principle he but half understood against a half-felt wrong.

The truth is that in 1873, when Douglas Hyde was thirteen, he could not have made any honest claim to being an Irish speaker. His excercise books indicate that what he then knew of the language probably was limited to at most twenty or thirty common phrases. These he had but recently begun to record as part of a newly serious effort to learn Irish, which until then he had simply parroted. His new method was to listen carefully to the Irish speakers who lived and worked on the glebe lands, at nearby Ratra, or at the edge of the bog; to repeat the sounds he thought he had heard; then like a magpie to take them home and store them in his exercise book, together with their meanings, using a phonetic system he had devised for himself. Such a primitive program of study was possible because, contrary to the conclusions of 1851 census takers who had identified northwest Roscommon (a sparsely settled midland area west of the Shannon, bordering Leitrim, Sligo, and Mayo) as largely English-speaking, when Hyde was a boy many men and women of hill, hollow, and bog (including those employed by Hyde's father and other local landlords) still spoke Irish among themselves or used a mixture of Irish and English in their daily lives. In the cottages of Frenchpark, Fairymount, and Ballaghaderreen, even in some of the houses in Castlerea, Irish was therefore the first language of countless very young children and the only language of most ould wans —women and men in their seventies, eighties, and beyond who spoke the local north Roscommon dialect that has now long since died out and who were revered for their wisdom and memory and respected as guardians of cultural lore and traditions. Contemporary scholars suggest that their dialect probably was close to the Irish still spoken today in Menlo, in east Galway.

The content of Hyde's beginning Irish vocabulary was restricted, of course, by the context in which it was learned. The first expressions he reconstructed in his exercise book involved shooting, drinking, agricultural chores, marketing, and the weather. Sometimes in the shop in Ballaghaderreen or at the fair in Bellanagare, he would eavesdrop on other Irish speakers, testing his comprehension. Although Hyde's

brothers shared his environment, neither took the trouble to learn to communicate in Irish, nor apparently did their father. It is almost certain that Hyde's upper-class schoolfellows in Kingstown would have known no Irish either. These were the boys whom Hyde apparently set out to impress with his blas (fluency), going so far as to pretend not only that he was bilingual, but that Irish was his native tongue. With twenty or thirty phrases at the ready to hurl into the contest he set up, there is no doubt that he would have had the advantage, if he had found anyone who considered a knowledge of Irish worthy of the challenge. Naive as he was at thirteen, with so little experience outside his native Roscommon (was this the reason why, in retrospect, he thought the incident in the schoolyard had occurred when he was only ten?), possibly he expected that his arcane knowledge would confer upon him the status a new boy always needs. His ability to rattle off an expression in Irish had won indulgent attention at home. Even his father, a Trinity graduate for whom education meant fluency in Latin and Greek, had shown interest in the increasing number of Irish words he was able to use, and Douglas's brother Arthur had told him that at Trinity College, Irish speakers were eligible to compete for a sizarship. "Maith an buachaill " (good boy) and "Good on you, boy," the country people of Tibohine would say, smiling and shaking their heads as if in amazement, whenever he mastered a new phrase.

Reactions in Kingstown were predictably different. To be sure, scholars did study Irish at Trinity College, then a bastion of Ascendancy attitudes and culture in the center of Dublin, but by "Irish" Trinity scholars meant the old language of Continental scribes that had been deciphered by European philologists, the classical language of bardic poets, or the literary language of chroniclers and historians artfully inscribed on parchment or vellum. Regarded not as the heritage of modern Ireland but as artifacts of a lost civilization, such manuscripts, many of them collected a century earlier for the Duke of Buckingham by Dr. Charles O'Conor, the duke's librarian, were accessible only to those who could qualify for admission to the libraries and manuscript rooms of Trinity, Oxford, the Royal Irish Academy, or the British Museum Library, or to such private holdings as the family archive of the O'Conors of Clonalis. But the unrecorded daily language of thatched hut and bog cabin? To suggest that such Irish had any relation to the language of the manuscript tradition was, to most nineteenth-century scholars, to equate the cries of Italian street vendors with the poems of Catullus and Horace or the superstitions of Greek seamen

with Homer's Iliad and Odyssey . No wonder the Kingstown schoolboys laughed and jeered.

By the time Douglas realized that, contrary to his expectations, native fluency (real or pretended) in modern Irish would not enhance his stature in the Kingstown school—that, on the contrary, it would actually diminish him in the eyes of the other boys—apparently he had gone too far to reverse himself. His spirited defense, if delivered at all (the words remembered in 1940 for delivery to Irish schoolchildren may represent only what Hyde wished he had said) no doubt seemed in retrospect the right answer to their jeers. In 1873, in a school for Ascendancy boys, it could not have been more than a brave front, after which Douglas returned to Roscommon and to a life that went on much as it had before.

To Dominic Daly, author of The Young Douglas Hyde, Hyde's Roscommon childhood seemed idyllic. Free from school routine, with a boat and a horse at his disposal, a dog for companionship, and unencumbered hours to spend rambling the countryside, boxing with local youths in the glebe house farmyard, playing cards in the kitchen with gamekeepers, stewards, and farm laborers, or listening to Irish stories before cottage fires, it had a Huck Finn quality. These were indeed pleasant days when together the rector of Frenchpark and his three sons constructed targets for rifle practice, checked the turlough in the meadow for waterfowl, hunted birds and rabbits, and rowed, sailed, and swam in Lough Gara. But Douglas's diaries also document tension and unhappiness, especially between sons and father; illnesses that eroded family relationships; and an angry resentment of the tyrannical and unpredictable behavior of the Reverend Arthur Hyde.

A microcosm of all that Trollope had portrayed of western Ireland, especially in The Macdermots of Ballycloran —its complexities misunderstood by Englishman and Dubliner alike, its way of life alien to the anglicized eastern establishment, its attitudes and values rooted in cross-currents of written and unwritten history—the town of Mohill in county Leitrim where the Reverend Arthur Hyde, Jr., grew up in the half century before disestablishment had defined for him the choices available to the son of a clergyman born in Leitrim in 1820 into the junior branch of an Ascendancy family. By heritage he was thoroughly Ascendancy, by social and educational background he was thoroughly Anglo-Irish. To continue in the family tradition, to become the fourth Reverend Arthur Hyde of the Church of Ireland, was for him an appropriate choice at a time when the social fabric and economic and polit-

ical mores of the west of Ireland could be counted on to support his taste for security on the one hand and independence on the other.

At Trinity College the Reverend Arthur Hyde distinguished himself as an excellent classicist. In the churches to which he was assigned he served as a man of the cloth on Sunday; the rest of the week he divided between his library, where he enjoyed the role of gentleman scholar, and the fairs, fields, and bogs where he was known as a handsome, devil-may-care country squire and sportsman. For his sons he wished no more than that they, too, should become country vicars, learn to shoot accurately and drink lustily, carry out their responsibilities civilly, and devote themselves, as behooved Hydes of their birth and breeding, to a gentlemanly kind of scholarship.

Scholarship was important to the Reverend Arthur Hyde: Trollopian in many respects, he was a dignified man, not a Somerville-and-Ross Church of Ireland minister. Proud of his achievements at Trinity (he had been awarded the bachelor of arts in 1839, when he was but nineteen, and a second-class divinity testimonium a year later), at home he quoted Greek and spoke Latin to his sons, insisting that they develop a similar fluency, especially before servants. (It was this practice, carried over by his sons Arthur and Douglas in their diaries, that resulted in entries in which "nova ancilla " signaled the arrival of the new housemaid, to be followed shortly by "ancilla expulsa est .") In Kilmactranny he was remembered as a man who eagerly studied the natural world, especially the medicinal properties of local plants and the habits of birds and animals. No subject was too esoteric to warrant his attention. Additions to the library of the glebe house were made regularly. Douglas notes in his diary that invariably the packages his father brought home from his frequent trips to Dublin included new books for the library shelves.

But the Reverend Arthur Hyde was neither so patient nor so reflective as his love of reading and scholarship might suggest. "Passionate" was the adjective employed by old Bertie McMaster of Kilmactranny when he recalled stories that the elders of his generation used to tell, of how the vicar bullied the young men of the parish into joining his cricket team, then raged at them during practice sessions for their unskilled performance; how he pilloried boys and girls who had not learned their Sunday school lesson; how he stopped in the middle of a Sunday sermon to scourge latecomers; how he was known for miles around as an exemplary shot—a man who, drunk or sober, could knock a magpie off a pig's back with a single bullet or catch a plover in flight.

In Frenchpark, in the pubs along the road between the village and Tibohine, local people who remembered the rector would say of him with a smile and a wink, "He was a playboy, he was."