Preferred Citation: Hatch, Elvin. Respectable Lives: Social Standing in Rural New Zealand. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2v19n804/

| Respectable LivesSocial Standing in Rural New ZealandElvin HatchUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1991 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Hatch, Elvin. Respectable Lives: Social Standing in Rural New Zealand. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2v19n804/

Acknowledgments

Photographs following page 90

This study has profited considerably from the help of others. Several people read an earlier draft of the manuscript, and their comments not only saved me from some serious errors but added considerable insight to the analysis as well: above all I thank Michèle Dominy, Cheleen Mahar, Eric Olssen, David Pearson, and Sandy Robertson. I am indebted, too, for the encouragement and good judgment of Sheila Levine, my editor at the University of California Press, and for the excellent help of Anne Geissman Canright, my copy editor at the Press, whose efforts have significantly improved this book. My family, Deanna, Kristen, and Catherine, also deserve thanks for their willingness to be uprooted for the duration of the fieldwork; Deanna, my wife, was also particularly helpful both in gathering information and providing perspective. Portions of the analysis were worked up originally as oral presentations at seminars and professional meetings, and I am grateful for the very helpful comments of those in the audience. The New Zealand portion of the research was funded by the National Science Foundation, while the California research was funded by a Public Health Service fellowship from the National Institute of Mental Health. My debt to both of these agencies is, of course, considerable. But the greatest debt of all I owe to the people of South Downs, whose hospitality, friendship, and patience seemed unlimited.

Chapter One

Introduction

People everywhere conduct their lives in milieux that are saturated with ideas about prestige—or standing, status, social honor, distinction. Certain features of a prestige structure or status system are within conscious awareness, such as who stands higher than whom; but much of it is not, including most of the cultural framework by which relative standing is defined. Any system of social rank entails a complex and unrecognized body of ideas—a cultural theory of social hierarchy—which is the basis of the hierarchical order and defines achievement for those who are part of it. These same ideas also help to shape one's sense of self, for they identify what kind of person one should be and what kind of life is worth living.

This book is about a small, sheep-farming community on the South Island of New Zealand, and its central argument is that the local system of social standing and conceptions of self are grounded in historically variable, cultural systems of meaning; thus, the social hierarchy cannot be perceived directly by the senses, because it takes form only when viewed from the cultural perspective of the people. These are also contested systems of meaning, for various sectors of the community have an interest in defining personal worth and social standing differently. A crucial part of the hierarchical order, therefore, is the processes by which these differences are worked out over time.

Choosing the Community

This study grows out of work that I did previously in a California community, a locality that consisted chiefly of dryland grain farms, cattle ranches, and a very small town.[1] A central problem of that research was the question of community. This locality was more than a “collocation of houses,”[2] for most of the residents displayed the sense that they had something in common, and whatever that was, it gave the district its identity. Part of what made this a community is that the people knew about and interacted with one another, and, more important, they participated in a set of institutions in which they had a common interest. They cared about the schools, for example, and about facilities for holding local events. But an equally if not more fundamental (and less obvious) aspect emerged as I lived there: that is, the community was a significant reference group,[3] and one of its fundamental features was a hierarchy of standing. Everyone in the district, whether they liked it or not, was placed by others within this hierarchy. People in the locality had their reputations at stake, or their local sense of personal worth and identity, and the dynamics of the community reflected this principle.

I later decided to pursue a similar study in another country, one similar enough to the United States both culturally and historically that I could undertake a close comparison. I also wanted to choose a community that would be very much like the one in California: it should be fully modern, and family farms should make up the economic base of the district. But above all I wanted a locality that exhibited the characteristics I described above: it should constitute an important reference group and a significant arena for social achievement, for I was interested in exploring the nature of the local status system.

I chose to do the work in New Zealand, and in 1978 I traveled from Auckland to Invercargill looking for a suitable place. The region of Canterbury, on South Island, seemed ideal, and, following the advice of people in the University of Canterbury and the Ministry of Agriculture,[4] I chose a community that I refer to as South Downs, a pseudonym.*

*I also use pseudonyms for other nearby localities and for personal names. I appreciate that there are serious disadvantages in so doing, the most important being that it impedes others from checking my findings. However, my material comes almost entirely from tape-recorded interviews and other conversations that cannot be “checked” as archival sources can. In any event, my overriding concern in using pseudonyms is to protect the privacy of the people studied, many of whom spoke freely about matters very personal to them because they understood that I would try to protect their identity. While the material in this book may seem innocuous to an outsider, much of it is highly sensitive to people in the South Downs district.

South Downs was ideal in part because it is a distinctly bounded community, as we shall see, and also because it is far enough from larger towns and cities that it exhibits the characteristics of a vigorous reference group. In March 1981, my family and I moved into a house in the township, and we stayed until just after the new year, over nine months in all.**

The Local Region

South Downs is several hours' drive south of Christchurch, which in turn is one of the leading cities of New Zealand and the focal point of Canterbury.

Much of Canterbury consists of the fertile Canterbury Plains, a long shelf, bordering the ocean, that was formed by alluvium washing down from the Southern Alps. The plains are devoted mostly to

**The primary source of material for this research was informal, open-ended interviews. Typically I chose to interview people I had recently met (at a shop, at a meeting, through a friend), and in some cases I contacted that person again somewhat later to discuss a new set of topics. In a few instances I had three or more interviews with the same individual. I began each session having a general idea of what I wanted to cover, but I did not use a formal list of questions, and the discussions often took wholly unexpected turns. The conversations were tape-recorded, and I transcribed them verbatim soon afterward so that I could refer back to them in preparing for subsequent interviews. Typically the discussions lasted from half an hour to over two hours. While the interviews were the cornerstone of the research, my immersion in the community was equally significant, for this provided background and context that were indispensable for interpreting the interview material. Because my children attended the schools, my wife and I participated as parents in both formal and informal school activities. My wife became a member of a variety of local organizations, such as the golf club, and I was incorporated informally into the Jaycees. I attended county council meetings, Lions Club events, Agricultural and Pastoral Association work days, and the like. My family and I were also drawn into numerous informal social activities. My two children made several very good friends, and my wife and I soon got to know their friends' parents reasonably well. My wife and I acquired friends of our own, and we soon became part of an established social network in the district. The people of this network (and the people we knew best in the community) were primarily middle-aged landholders at the mature stage of the developmental cycle.

mixed farming, although even the most casual observer can see that sheep are especially important in the region. Serving the farms is a network of villages and towns, the most important of which are located on the main railway line.

The width of the Canterbury Plains varies, reaching a maximum slightly south of Christchurch, but at any spot the topography follows a common pattern. If we begin on the coast and proceed directly inland, traversing the plains at a right angle, we eventually come to the foothills or downlands. These are intersected by a series of rivers that run more or less parallel to one another and flow directly across the plains and into the sea. Moving into the downlands we continue to climb in elevation, until eventually we come to the base of the Southern Alps, which are steep, rugged, and high enough for glaciers to form. Passage over the mountains to the West Coast of South Island is possible only through a few difficult passes; consequently the Alps form a very effective divide between Canterbury and the West Coast.

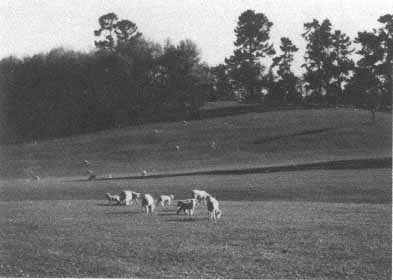

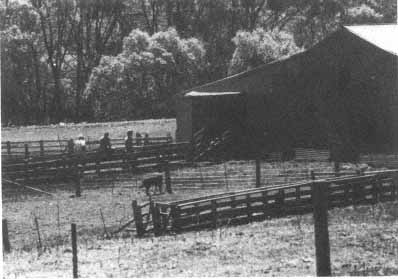

The county of South Downs is located in the downlands and is divided into three main parts. First is the district of South Downs, or South Downs proper, which occupies the upper two-thirds of a narrow valley some thirty miles long; the valley floor is about 1,000 feet above sea level, and above it the hills rise another 2,500 to 6,000 feet. The township of South Downs, located in the valley bottom, has a population of about nine hundred, with another nine hundred individuals populating the surrounding farmland. The district is devoted almost entirely to sheep, although a few cattle are raised and some wheat and other crops are grown. These are predominantly farms, not runs,*** although a few runs occupy the higher and rougher portions of the district.

The second section is Midhurst, which occupies the lower end of the same valley. Midhurst has a township even smaller than that of South Downs, consisting of slightly over one hundred people; the Midhurst district as a whole also has fewer residents—less than five hundred all together. Like South Downs, most of the landholders in Midhurst are sheep farmers, although again, some sheep runs are located in the higher and rougher regions.

The third section completes the county. This is the Glassford dis-

***This distinction is based on differences in property use. A farm is characterized by intensive agriculture, including cultivation of the soil, whereas a run is extensively farmed with little if any cultivation.

trict, with a population of nearly fifteen hundred and including a township of slightly more than three hundred people. Taking in the comparatively high country situated between South Downs and Midhurst, on the one hand, and the Southern Alps, on the other, Glassford is topographically diverse, a combination of relatively flat land, steep hills, and the slopes of the Southern Alps. The area is considered very cold, difficult country, and the properties there are quite large, since several acres are needed to feed a single animal. These are runs, not farms; here, sheep are grazed to as high as the animals can forage during summer, and whereas the properties in the South Downs and Midhurst districts generally are between 350 and 500 acres, in Glassford they are several thousand at least. Many of these runs are very isolated, a fact that has helped to stimulate a strong sense of community among the run-holding families there.

These three districts are thought of as separate but closely related communities, and what underlies their common identity is that they form a single county. Each district elects its own representatives to the county council, which among other things oversees the roads and bridges of the region, a matter of considerable interest to land-holders.[5] The three districts also share the same high school and are part of a single telephone system. In a sense the South Downs district is the most notable of the three, in that it has the largest population and its township contains the greatest number of businesses; the county offices, high school, and telephone exchange are also in the South Downs township. Nevertheless, the Midhurst and Glassford districts do not see themselves as subordinate to South Downs, but rather as equal (though grudging) partners. Indeed, Midhurst tends to see itself as slightly superior to South Downs: it thinks of itself as a more cohesive community and of its farmers as more progressive. And the Glassford district sees itself as superior to both, since run-holding confers greater distinction than farming.

The most important basis for the distictiveness of each of these districts is that they have separate social hierarchies. Landholders know all the other farmers and run-holders in their own district and can place them at least roughly in a single hierarchy of standing, but that hierarchy stops at the borders of the district. For example, virtually every farmer in the South Downs district can discuss the quality of the sheep and paddocks of any other South Downs landholder, and he can comment on his credit worthiness, business acumen, financial well-being, and so on—all of which (among other things)

are important for placing that person within the local social order. The same farmer may know most of the Midhurst landholders by name, and some by reputation; but he would have trouble placing them in a hierarchical order, and in any event he would resist trying to place them within the hierarchy of his own district.

The boundedness of these communities reflects the topographic characteristics of the region. The three districts are divided not only from one another but from still other communities by natural boundaries: mountain ranges, escarpments, and rivers. In this respect these communities are unlike other Canterbury farm districts located on the plains, where natural boundaries are fewer and communities tend to overlap or merge a good deal more.

The three districts are not isolated, however. They are geographically part of, and they identify with, a larger subprovincial section of Canterbury. The east-west borders of this subprovincial section are defined by the ocean and the Southern Alps, respectively, and the south-north borders by major rivers. The people living in South Downs county know the names of at least a few of the leading people in each of the communities making up this larger region, and many have friends and relatives in nearby communities as well. At the economic and symbolic (but not the geographic) center of the subprovincial region is Jackson, its largest town, situated on the main railway line. Most people living in the county of South Downs travel to Jackson several times a year at least. Teenagers sometimes drive there for the evening to see a movie, and many families shop there once a month or so; most landholders visit their accountant there a few times a year, and possibly their banker as well. People also travel occasionally to Christchurch either for business or pleasure, though the drive is long enough that very few do so regularly.

In this study I focus chiefly on the hierarchy of the district of South Downs, and only secondarily on Glassford and Midhurst.

Standing and Personhood

Two main theoretical principles underlie this book. The first is that social standing, achievement, and personal worth or identity are central to most social systems. Consider the Trobriand Islanders.[6] Trobriand yam gardeners were oriented not so much to-

ward the problem of subsistence—or toward sheer material survival—as toward the goal of maintaining or achieving a good name for themselves, their families, hamlets, and villages; this they did largely by growing very large quantities of healthy, robust yams. The relations among groups were essentially competitive ones, whereby the members sought to establish their standing and respectability through yam gardening.[7]

Similarly, Pierre Bourdieu argues that the issue of standing or achievement is central to the dynamics of modern French society.[8] According to Bourdieu, the dominant class in France is made up of two parts: one, chiefly the major industrial and commercial employers, enjoys a large volume of economic capital, while the other, including artists and professors, enjoys a large volume of cultural capital. The two segments are engaged in what Bourdieu calls a classification struggle, in which each seeks to advance its own criteria both for measuring standing and for defining the meaningful and worthy life.[9]

The second principle underlying this book is that status systems are grounded on systems of meaning. Thus, a main task of the analysis will be to render those meanings. This is not all that the research should do; it should also attempt to understand the actions of individuals—to analyze the avenues of achievement that are available to them, as well as their attempts to alter the system to their own advantage by changing the cultural definitions of social standing and personal worth. Yet because the actions of individuals are unintelligible outside the context of their cultural ideas, understanding the cultural framework is an essential step in this study.

To appreciate the force of this point, consider the social structural theories that have sought to explain differences in the prestige of occupations in Western societies.[10] These theories tend to naturalize the processes that underlie prestige, or to assume that certain qualities “naturally” stimulate respect or admiration in the individual's mind. For example, Donald Treiman asks rhetorically why positions that enjoy power and privilege everywhere are accorded high standing (a generalization, incidentally, that needs to be seriously qualified if it is to be accepted),[11] to which he replies: “The answer is simple—power and privilege are universally valued in all societies.”[12] For Treiman, then, it is a natural process of human thought to look up to, admire, or envy persons or positions that exhibit these features.

Treiman states explicitly that his theory applies only to occupa-

tions and not to the differences in prestige among, say, ethnic groups or family names, but this caveat seems disingenuous.[13] He holds that his theory explains why the same occupations tend to rank at about the same level in all societies; clearly, in his view, a powerful force is at work, which is the desirability of power and privilege. To be consistent, he must extend the same explanation to other parts of the status hierarchy: for example, to state that if one ethnic group enjoys greater power and privilege than another, it must also enjoy greater prestige.

Jonathan Turner expresses a view similar to Treiman's. Turner argues that, in general, the prestige of a social position reflects the degree to which it exhibits the qualities of power, skill, functional importance, and material wealth. These four attributes, he further suggests, attract prestige because of “a social psychological process”—by which he seems to mean that people “naturally” look up to social positions and individuals that manifest these qualities.[14] Parallel assumptions are widespread in the social sciences; for example, Robert Murphy remarks that “in hunting societies, a successful hunter will generally be accorded considerable esteem, for he shows excellence in a pursuit basic to the group's survival.”[15] Hunting peoples, like everyone else, “naturally” admire the individual who contributes significantly to the group's material well-being.

My argument in this book is that people are not naturally attracted to certain attributes, for what is desirable, prestigious, and fulfilling is defined by culturally variable systems of meaning. Hence the critical starting point for the analysis of a prestige or status system is to render the meanings that underlie it.

Not only are the values that define what people look up to cultural and not natural, but so are the signs by which the individual judges the relative standing of a social position. Consider Treiman's theory once more. In his analysis the attributes that signify social standing are “natural” signs, the meanings of which are self-evident or transparent. On the one hand they are brute facts, directly observable by the senses; a person can literally see both the exercise of power and differences in material well-being. Thus, in principle, disagreements between two people over the relative prestige of an occupation can be resolved by appealing to objective facts: how much power does the holder of the occupation actually wield, and what is the level of his or her material compensation?

On the other hand, in Treiman's analysis universal standards are used to interpret the objective signs of social position, with the implication that the signs making up the status system of any one society are directly intelligible to the members of any other society. For example, the power and material advantages that distinguish the high-prestige occupations in our society should be as clear to another people as they are to us—one only has to look to see that the well-to-do drive better cars, have physically easier or more interesting work, own more labor-saving devices, eat better food, and live in larger and more comfortable homes. Similarly, we need only look to appreciate that the headman in a chiefdom is better off and enjoys greater power than his subordinates.

Bernard Barber has also studied occupational prestige. According to Barber, an occupation's standing is determined by its importance for the continuance of the larger society: the greater the functional significance of a role, the greater its prestige. What is more, he suggests, “most people can make pretty good estimates of what the functional significance of the various occupational roles actually is.”[16] Thus, the quality or attribute of functional significance constitutes a set of signs for judging social standing, and the sociologist who analyzes occupations in terms of their functional significance “sees” approximately the same hierarchy as the people who view the system from their own perspective. All parties see the same brute facts that are directly observable by the senses, and they apply universal standards in interpreting them.

In this book I argue that the signs that people read when they view the social hierarchy not only are defined by cultural meanings, but they cannot be perceived apart from those meanings. For example, the economic order is an important arena of achievement in both New Zealand and California, with wealth an important factor (or set of signs) for assessing social position in both places. Yet wealth is defined differently in the two locales, with the result that the signs of wealth are different. A California farmer, stepping into a New Zealand farming community for the first time, would “see” a different hierarchy of wealth from what the New Zealanders do.[17] Similarly, if a European man were to step into a Kachin gumsa community in Burma for the first time, he would be unable to “read” the rank of the lineages residing there because he lacks the cultural framework for doing so. By contrast, if a Kachin man from another

community were to enter that same village, he would be able to order the local lineages relatively easily, since he understands the symbols that express rank.[18]

I have mentioned that the systems of meaning need not be fully agreed upon, because segments of society have an interest in altering the definitions of social honor and personal worth. Even in the absence of overt competition, it may be common for individuals to employ somewhat different cultural meanings in regard to the status system; consequently, they may render somewhat different interpretations of the same signs. For example, a handful of families in South Downs possess religious convictions that lead them to define moral worth by principles different from the ones I analyze. Yet the investigator has no choice but to try to enter into the cultural world of the people, however fluid and diversified it may be, if he or she is to render the status system intelligible.

It is important to be clear that South Downs is not a homogeneous community and that the patterns I describe in this book are not fully consensual. What I have set out to do here is explore the internal principles or patterns of a particular cultural system to which people adhere at various times and to varying degrees. While this is not the only cultural system for defining social hierarchy and moral worth within the community, I suggest that it enjoys a unique status among its rivals, for it is the dominant system in the district. A lack of consensus need not imply anarchy.

The Issue of Gender.

The issues of heterogeneity and dissent lead directly to that of gender, for concepts of moral worth and personhood in South Downs are different for men and women. Although gender receives little explicit treatment in this book, its significance is pervasive.

The place to begin is with a cultural ideal in South Downs concerning the differences in men's and women's relationship to the economic order. According to this ideal, men are active agents in the economic sphere—in principle, they are the ones who engage in business affairs—whereas women are dependent on the men's roles in the workplace. The strength of this model became apparent when

one of the firms in the South Downs township was forced to lay off some employees. The policy they adopted was to dismiss married women first, before any of the men, regardless of seniority; the grounds for doing so were that men are the primary breadwinners in the household, whereas the married women had men to support them. Virtually everyone I spoke to, men and women alike, regarded the policy as fitting.

The strength of the model is also manifest in the concept of the farmer. A woman may own a farm by herself, and conceivably she could do all the work on it that a male owner would do (though I know of no case in South Downs where this was true); but even so, to refer to her as a farmer would strain normal usage to the limit.[19] The business of farming is conceived as inherently masculine, and this is so even though women's labor is extremely important on many properties, especially during the early years of ownership when there is insufficient income to hire other help. A woman may be highly regarded for her contribution to the farm operation, yet the labor she provides is considered supportive, not primary, and in an important sense she is viewed as subordinate to her husband in the operation of the business.

This conception of the relationship of men and women to the economic system corresponds to local ideals concerning the social hierarchy. Here, the status system is regarded as a hierarchy of households that draw their standing from the male household heads, and the position of women derives largely from the standing of the households to which they belong.[20] Thus a study of the social hierarchy is essentially a study of the occupations and activities of men.

Reality presents complications that confuse the ideal models I have described. An example is a schoolteacher—a woman—whose occupation ranks substantially higher than that of her husband, a truck driver; another is the handful of adult women in the community who support themselves and their children on their own. Nonetheless, the ideal provides a dominant framework that community members use in representing the local social order.

The implications of this folk model for the present study are considerable. On the one hand, the focus of the research is decidedly on the affairs of men, not women, simply because the local social hierarchy is defined primarily in relation to males. On the other hand, this folk model implies that a man's sense of self-worth and achievement is developed largely in the context of a masculine-oriented

social hierarchy. A man measures his achievements primarily in relation to men and by reference to masculine affairs.

It has been suggested that hierarchy means different things to men and women and that ideals like those described here are not gender-neutral at all; in other words, they do not represent a middle standpoint shared by males and females equally, but reflect the perspective of men specifically.[21] According to this argument, women's voices and perspectives tend to be suppressed by male-gendered ideals like the above. In the research for this study, I was careful to include a wide range of women. Because these women seemed to express the ideals I have described as adeptly and as readily as the men, I have no reason to think that gender differences do exist in regard to conceptions of the social hierarchy. Yet I was not particularly sensitive to the question of male/female perspectives when I was engaged in the field research, and I did not inquire specifically into the question. Consequently, I do not claim that the analysis presented here is gender-neutral, or that everyone shares the perspective that prevails in this work, that is, that women's standing in both the economic order and the social hierarchy is different from that of men. Rather, I attempt to explain how the social order looks and works when it is seen from the viewpoint of—or from within—the perspective I describe here.

The issue of gender enters into this study in another crucial sense as well. Because occupation is so central to conceptions of personal worth and social standing in the district, I devote a good deal of attention to the cultural ideas underlying the local occupational system. Yet the work that people do in the economic sphere defines personal identity very differently for men than for women. Although occupation may be extremely important for a woman's sense of selfworth, it is not central to her gender identity, whereas it is for a man's.

Consider the case mentioned above, in which a local firm, forced to retrench, laid off some of its women employees. One of these women, who had worked for the firm for many years, was severely affected personally by the loss of her job. I suggest that an important reason for her upset was that her personal identity had come to be defined largely by her employment. Her identity as a woman, however—her gender identity—was unaffected by her joblessness.

By contrast, a man's identity as a man is importantly (though not completely) defined by his work.[22] Unemployment may thus be a

feminizing experience for the male, and the same may be true when a wife is significantly more successful in the economic order than the husband. For a man, achievement in the occupational sphere means not only the improvement of his social position, but also the affirmation of his gender identity.

The idea that occupation means something different for men and women is suggested implicitly by Michèle Dominy, who argues in a recent study that the gender identity of “traditional” New Zealand women is defined chiefly in terms of an ideology of motherhood.[23] The cultural ideal identifies the role of homemaker or the woman's activities in the domestic sphere as definitive for her sense of feminine self-worth. Yet this ideal also allows for the inclusion of certain nonhousehold activities—including public service or voluntary activities that are conceived in terms of the domestic or nurturant model—which may contribute significantly to a woman's sense of feminine self-worth as well. Dominy suggests, moreover, that through such participation women may achieve considerable influence in the public sphere. The woman's achievement of gender identity through her activities both in the home and in voluntary public service may, I believe, be further regarded as an analogue to the man's achievement of gender identity through work.

Rather than being irrelevant to this study, then, gender occupies a central place in it. This is true in two senses. First, the book is written in the masculine voice. It assumes what may be a male-gendered perspective, by which men and women are conceived as standing in a different relationship to the economic order and social hierarchy, with women under the mantle of their male household heads. Second, it focuses largely on occupation, which is central to the gender identity of men, not women. This book may thus be regarded not as a study of personhood in general within the district, but of male personhood specifically.

My analysis of South Downs begins with an account of the occupational system, a comprehensive framework for ordering all the households in the district. First I present the “shape” of this system, or the hierarchical pattern that emerges when the local occupations are viewed as an inclusive set; I then analyze the grounds that people use in assessing the relative standing of the positions that make up this set. My purpose is to suggest the more or less implicit principles that are constitutive of the hierarchical order, principles, I argue,

that are cultural, not natural, for they are historically contingent. Next I focus on the most important occupational category in the district, landholding, the goal again being to understand the system at a level that is largely beyond the conscious grasp of the people themselves. The landholding families are ordered on the basis of three primary—and also culturally variable—sets of criteria: wealth, farming ability, and refinement. The definition of wealth among landholders in South Downs is different from that of the California farmers I studied earlier, as noted; similarly, the criteria of ability and refinement rest on cultural theories of social hierarchy that have undergone significant modifications since the 1920s as a result of the vicissitudes of history. What is more, these last criteria—ability and refinement—lead directly to the concept of person, for each implies fundamentally different ideals on which the individual models him- or herself.

Before starting with the analysis of South Downs, however, I need to sketch the history of stratification in rural New Zealand. This will provide context that is essential for what follows.

Chapter Two

The Historical Pattern

The earliest year-round European settlements in what is now New Zealand were established in the 1820s and consisted of whaling stations and Christian missions.[1] Shortly thereafter a growing interest was expressed by British citizens in claiming the islands for colonial settlement, and within a few years the British government acceded to the demands. Britain annexed New Zealand in 1840, making it a Crown Colony the following year.[2] New, permanent settlements soon appeared on both North and South Islands, two of which were particularly important for the present study. One was Otago, founded in 1848 at the site of the present city of Dunedin by adherents of the Free Church of Scotland, with the original colonists chiefly Presbyterian Scots.[3] The other, the Canterbury settlement, founded in 1850, was Anglican and was established at what is now Christchurch.[4] As we shall see, in South Downs the distinction between the Scots and the English, and between Otago and Canterbury, was to occupy a prominent spot in people's discourse about interpersonal relations.

A guiding principle behind the Canterbury settlement was the idea of recreating the British rural hierarchy, whereby the citizenry would be dominated by country gentlemen—men of means, education, and high standing, and also devout Anglicans. The dominant class would have a strong sense of obligation toward their inferiors, a sense that had declined in England and Europe, it was believed, owing to the selfish pursuit of wealth that had become so prominent with industrialization. The guiding figures behind the Canterbury

settlement therefore opposed social equality, for they believed that the lower classes would achieve high standards of civilization only if they lived in an environment of discipline and order.[5] The social hierarchy that the Canterbury organizers had in mind for the new settlement was manifest in the terms that distinguished the two main classes of settlers. “Colonists” were those who could pay their own passage and who had the capital to purchase land, whereas “emigrants” were laborers and artisans who came as assisted passengers: being unable to pay their fare, they were assisted in emigrating by funds from the Canterbury Association.[6]

The plans of the organizers went awry almost from the start. For one thing, it was difficult to convince members of high social and economic standing to come to this distant land. The “colonists,” it seems, were chiefly men and women of the middle classes.[7] Another problem was that upward mobility for working people was easier than expected. The demand for labor pushed wages up, and land was fairly cheap, so substantial numbers of working people were soon able to acquire small farms of their own. As a result, working people developed a strong sense of independence, and both social and economic relations in New Zealand acquired a strongly egalitarian cast almost from the start.[8] Significant differences in wealth existed within the colony, to be sure, but these differences were not associated with patterns of social deference like those in England.[9]

In the earliest stage of settlement the farms were devoted exclusively to feeding the small local population, but by the early 1850s land was being put to a new commercial use. This new use was very different from what the settlement's founders had envisaged, however, for it was soon realized that the Australian system of sheep husbandry was the most feasible economic enterprise for the new colony.[10] This was not a system of small farms raising such agricultural goods as grain, vegetables, and dairy products for local consumption. Rather, the holdings consisted of vast sheep runs devoted to extensive pastoralism, with the land remaining (at first) in its native tussock. A run consisted of at least ten thousand acres and was inhabited by only a handful of people—the run-holder's family, together with a small hired staff of shepherds and other station hands.[11]

Not only was land cheap, but it could also be acquired as leasehold from the Crown, at least initially, and the lease payment was not due until the wool clip was sold. According to one account, £1,050 to

£1,200 was needed to start a sheep station during the early years.[12] This was enough to purchase a small flock of eight hundred to a thousand breeding ewes, employ hired help, make a few improvements to the property (for example, a small hut was needed until a proper house could be built), and provide a small amount of working capital. The land itself did not require much labor, since sheep thrived on the native tussock; and fences were unnecessary to begin with (boundary keepers could be hired to prevent the flocks of neighboring stations from becoming mixed). The system had the added advantage that it was easy to learn, so inexperience was not a great handicap.

The sheep were raised for their wool, not the meat, for until the 1880s the meat could not be shipped abroad without spoiling. The local people consumed some of the animals, but the sheep population quickly exceeded the human head-count. Because the wool was what mattered, the dominant breed was the small, temperamental merino, which produces meat of only modest quality but grows a large amount of fine wool. The merinos require very little labor; indeed, they can be left to themselves most of the year. On many stations they were mustered only once annually to be shorn, when the lambs were also marked and the entire mob was treated for disease.[13]

The original run-holders in Canterbury fell into two distinguishable categories. First were people already established as pastoralists in Australia who saw fresh opportunities in New Zealand and quickly moved there, bringing both capital and a knowledge of sheep production. The second were the Canterbury pilgrims who were sufficiently well-to-do to establish sheep runs of their own.[14]

The Scottish settlement at Otago underwent a similar transformation as a majority of the land became devoted to wool production. There, however, few if any of the original settlers joined the ranks of the early run-holders, since these early immigrants were in general even poorer than the Canterbury settlers and so lacked the capital needed to occupy and stock the runs. Rather, the original Otago run-holders were chiefly Australians on the one hand and a few Canterbury settlers on the other; collectively, they were identified as English and Anglican, and thus represented a challenge to the early Presbyterian dominance in Otago.[15]

By the 1860s virtually all of the land of Canterbury and Otago that was suitable for pastoral use had been claimed.[16] Sheep runs

were now the economic backbone of the colony, and they produced almost exclusively for the international wool market.

Although the pastoral system was well beyond the means of working people, the man who wanted to farm could find other opportunities. A local market existed for farm goods like vegetables, fruit, grain, and milk products, the supply of which could be undertaken by small, affordable family farms. The areas surrounding towns such as Christchurch, Ashburton, and Dunedin were soon devoted to agricultural production for the local market. Most of the work on these properties was done by the farmer himself and his family, because the cost of labor was too high for hired help to be profitable.

The local food market expanded over time as New Zealand's population grew, and this in turn facilitated upward mobility. One important source of population growth was the program of assisted immigration from 1855 to the 1880s, whereby agents in England organized a regular flow of workers to the colony;[17] another was the gold rushes in Otago and the West Coast during the 1860s, which brought a sudden influx of people from such places as Australia and the United States. Still, the local market was severely limited, as were the opportunities for upward mobility that this type of farming provided; all told, a mere fraction of the population could produce all that the people needed.

Wheat Farming

Between 1875 and 1895, wheat came to rival wool as an export item in New Zealand, a development with important implications for the local social organization, especially on the Canterbury Plains.[18] An example is the Longbeach estate near Christchurch, which, though originally claimed for the purpose of wool production, for a period became one vast wheat farm employing up to three hundred men at the peak of harvest.[19] The owners of Longbeach, who were among the most innovative in the development of wheat production, were not alone, for a number of Canterbury landholders kept twenty or thirty teams busy all summer.[20]

One very important effect of the wheat boom was that it created a sizable need for farm workers, most of whom, however, could find

work only during the busy summer months. Another effect was to increase the range of differences among large landholders. Initially all large property-holders operated their holdings along similar lines, as sheep runs; but now those in a position to take full advantage of wheat production were able to engage in a very different form of agricultural enterprise.

Several factors limited the landholder's ability to shift to wheat, one being that some properties were more suitable than others for this type of crop. The hilly and mountainous regions were too steep for the harvesting equipment that was used and typically lacked drinking water for the draft animals. Rather, the properties that could make the shift were located chiefly on the plains, in the river valleys, and on the downlands adjacent to the plains.[21] The rougher areas, and particularly the high country, remained in tussock.

Yet the properties that turned to wheat never fully abandoned sheep farming. When the tussock was first plowed, the soil was rich and productive, but soil exhaustion set in after two or three years. The landholder eventually plowed the wheat stubble into the ground, planted permanent English pasture grasses, and returned to full-scale sheep production.[22] The conversion to exotic grasses was highly desirable, because pasture of this kind supported a larger number of sheep per acre than tussock—perhaps tripling the carrying capacity.[23] The wheat boom in Canterbury thus ended up increasing sheep production considerably on the properties that switched to grain crops.

The wheat boom was important for another reason. Because wheat farms did not have to be large to be profitable, this form of agriculture was within the reach of men with limited means—as long as they were able to do most of the initial back-breaking work on their own. The wheat boom made it possible not only for farm laborers to move into the ranks of farm owners, but also for many small farmers to acquire larger holdings.

During most of the 1870s small farmers felt reasonably prosperous, while the young man starting out found that loans and therefore farms were relatively easy to acquire. But suddenly, in 1879, depression set in, lasting until 1896.[24] A farmer who had purchased his land in the 1860s, say, before the inflated land values of the seventies, was able to establish himself on a secure basis before the depression got under way; but the person who bought a farm in the late 1870s was likely to lose his investment.[25]

Acquiring a Small Farm

An account from Otago in the 1880s describes how an agricultural laborer set out to acquire land in that period.[26] He might buy about fifty acres of unimproved land, at a price of perhaps £2 an acre. This would probably take all the money he had. Lacking the capital to buy a horse, he got to the farm by walking, carrying his tools on his back. Having purchased seed potatoes and rations from farmers living nearby, he then made camp on his property. After the potatoes were planted and he had done what he could to improve the land, he walked back to a more settled district, where he found work to support himself and his family, whom he had left behind. When the potatoes were grown he returned to his farm, planted a larger crop, and built a primitive shelter for his family. The family moved to the farm as soon as they had a crop of wheat to make their own bread, as well as vegetables and potatoes for their own use. They raised poultry and, if they could afford it, bought a cow. To supplement their diet they hunted pigeons and wild pigs and fished for eels. The farmer slowly upgraded the family dwelling and increased the amount of land that was cropped, relying less and less on subsistence farming and more and more on cash cropping.

The case of one Ashburton settler, Thomas Taylor, provides a detailed look at the process.[27] Taylor emigrated to New Zealand from Ireland in 1864, when he was twenty-three. He landed in Auckland, where he got work as a carpenter, but when gold was discovered on the West Coast of South Island he set off to make his fortune (presumably in 1866). His tour as a miner was reasonably profitable—until his gold was stolen, whereupon he set off on foot across the mountains, carrying his few belongings in a swag, to find work in Canterbury. Taylor worked for several years as a farm laborer and threshing-mill driver in a farm district outside Christchurch, where, soon after his arrival, he also leased a small farm plot that provided additional income. At one point he entered into a partnership in a flax mill, but this proved unsuccessful, and once again he lost virtually everything he had.

Taylor continued saving as much of his wages as he could, and in the early 1870s—he now had a wife and two children—he went to the land office in Christchurch to consult the official maps of available properties. He decided on a plot of two hundred acres near

Ashburton and drove there in a trap to see what it was like. Although the land was swampy and covered with a thick and tall growth of flax, he decided to purchase it anyway. He returned immediately to Christchurch to pay his deposit; payment of the full price could be deferred until a future date.

While his wife and children stayed in the farm district near Christchurch, Taylor set out for the new farm, accompanied by a man he had hired to help with the move. The two men drove a dray loaded with equipment and supplies, and they camped in a tent when they arrived. Immediately, however, they set to work building a sod hut for the family to live in, and Taylor brought his wife and children to the farm when the small home was built but before the farm was actually in production. During the first years on the property he worked as a carpenter, building the houses of other settlers who had purchased small farms nearby—with payment often in kind, for his neighbors were as poor as he. Taylor's wife raised fowl, and they had several milk cows; with the money thus earned, plus what he made as a carpenter, the family was able to survive until farming was fully under way. Taylor must have dug a system to drain the swampy areas before he could begin farming, and he had to plow the flax and seed the land, but by about 1877 his enterprise was on a solid footing as a mixed farm devoted to both dairying and cropping. His main crop, presumably, was wheat.

It is significant that Taylor acquired his farm in the early 1870s, for the price he had to pay for the land then was probably much less than it would be just a couple of years later. In addition, his farm was in production during a good part of the prosperous 1870s, so he was probably able to clear his debts before the depression set in in 1879. Had he delayed another five or six years in buying the property he might not have succeeded.

Social Hierarchy in the Late Nineteenth Century

I want now to present an overview of the stratification system of rural New Zealand in the last two or three decades of the nineteenth century.[28] I focus largely on male occupations, since I assume that the single most important factor in assessing class stand-

ing was the occupation of the household head, who typically (and certainly in theory) was a man.

The lowest of the three primary occupational categories comprised workers or the working classes.[29] The run-holders hired yearround crews of shepherds, boundary keepers, general laborers, and the like, as well as occasional or seasonal workers, particularly shearers who came to the station in gangs for a few days each year to work the mob of excitable merinos and half-breds. The need for hired workers was even greater on the farms than on the runs; some farms were large enough to require year-round help for such jobs as plowing, fence building, and tending livestock, and virtually all farms required some additional help during the summer for harvesting and sowing. The workers were hardly homogeneous, and it is reasonable to suggest that one basis for sorting them was by the skills that their jobs required: surely a teamster enjoyed a higher standing than the unskilled laborer who acquired occasional jobs digging drainage ditches and cutting gorse hedges. This measure suggests another, namely income. Some jobs were better paid than others, and some provided more regular employment. Only a minority of rural working men had year-round jobs; most were hired on a temporary basis by farmers and run-holders and so were idle during at least some of the winter, when even the farmer himself had little to do. The problem of winter unemployment—indeed, of unemployment in general—increased during the long depression of 1879–96, when a constant stream of itinerant swaggers moved from station to station in search of handouts. The swagger occupied the very bottom of the rural social ladder in New Zealand.

The second category of this rural hierarchy included the small farmers, who were referred to as “cockatoos” or “cockies,” a term imported from Australia, where the avian cockatoo was considered a pest: in New Zealand as in Australia, the “squatters” (or large pastoralists) found the small farmers a serious nuisance.[30] Because many of these men began their careers as hired workers, we might assume that their life-style was similar to that of the people below them. Yet the evidence from South Downs suggests that not all cockies were of the working classes or exhibited working-class patterns. At least a few came from middle-class families—some were sons of minor English clergymen or small business owners, for example. These were people who paid their own passage to New Zealand and who had financial resources beyond what they might earn in wages,

but whose wealth was sufficient to buy only a farm, not a run. In turn, they probably exhibited somewhat greater “refinement” in lifestyle than either working people or farmers with working-class roots[31] —one significant criterion for distinguishing among farmers. A second criterion was wealth. Some farmers were barely able to afford a very small plot of land, at least at first, whereas others had sufficient resources to buy larger and better situated properties. Some of those who acquired their holdings early (say, in the 1850s) were relatively prosperous by the 1880s, even in spite of the depression—including many of those with working-class backgrounds who exhibited a working-class life-style. By contrast, those who acquired their farms in the mid to late 1870s were, in the next two decades, in a very precarious financial position.

The third social and economic category comprised the large landholders, sometimes referred to as New Zealand's “gentry”;[32] they were set apart from both the working classes and cockies not only by their greater wealth but also by the fact that they employed, and thus had direct authority over, large crews of workers. The average estate in one county on the Canterbury Plains, for example, employed twenty men full time.[33] In 1890, one prominent squatter and a member of Parliament, Captain Russell, commented that he could put a small country settlement for working people, “the whole lot of them, settlers, sheep, cattle, and all, in a corner of my run, and not know they were there.”[34] Because large landholders were typically better off financially than the rest of the population, they could afford a more elegant way of life, including in many cases fine homes surrounded by several acres of gardens and the attendance of uniformed servants and a crew of gardeners. Yet it would seem that differences in life-style were not a function simply of wealth, but of class background as well. In Canterbury at least, the large landholders included a significant number who came to New Zealand with what the working and lower middle classes would have considered a rather highbrow way of life. A substantial number of them were educated in English public schools, for example, and a few had attended either Oxford or Cambridge.[35]

Still, the large landholders, like the cockies, were a heterogeneous group. For one thing, they represented a wide range of social backgrounds. Oral history from South Downs, for instance, includes cases of very poor Scotsmen who immigrated to New Zealand to work as shepherds on the large estates and proved to be especially

capable sheep men; before the end of the century some had acquired small or moderate-sized runs of their own, often in remote and difficult areas where the original run-holders had failed, and at least one astute and experienced Scots shepherd eventually became a very wealthy landholder. For another, run-holders differed considerably in wealth. Some had holdings that were small, poorly situated, and barely profitable, whereas others owned or leased several estates, any one of which could support a family in elegant fashion.

Despite the differences among run-holders, they tended to become linked together in a common social network, which was facilitated by a variety of institutions. In Canterbury, for example, it was common for the families of the large landholders to visit Christchurch regularly, and many had residences there. The social season in Christchurch was marked by a busy schedule of dinner parties and visiting among the well-to-do.[36] The countryside also had a relatively genteel social life dominated by some of the local run-holders. This included such private social events as dinners and tennis parties, as well as “public” affairs like hare hunts, using hounds brought from England. Since the large landholders tended to intermarry, many were related to one another through ties of kinship and affinity; many had also been to private boarding schools together, and some even to public schools in England.

The line between run-holders and cockies was somewhat indefinite and permeable. Some of the more affluent and “respectable” farmers participated in such events as hunts, for example; and in terms of sheer life-style, cockies from an upper-middle-class background probably had more in common with the more genteel runholders than did some of the very wealthy people with working-class roots.

I focus here on rural New Zealand, yet scattered throughout the colony were population centers of various sizes. These were inhabited chiefly by the working and lower middle classes, including the men who provided the seasonal labor on the farms and stations, artisans such as bootmakers, small shopkeepers, and the like. The towns typically included a more affluent middle class as well, made up of such medium-sized business owners as drapers and auctioneers, and a few lawyers and doctors. The people of highest standing in these communities were sometimes included in the run-holders' social circle as well.

Relations Among Classes

The relations among classes are as important a topic as the class distinctions themselves. I mentioned that a more egalitarian ethos prevailed in nineteenth-century New Zealand than in England, by which I mean that the markers of social distance, or the observable symbols by which social hierarchy was publicly expressed, were less pronounced in the colony. For example, it was probably easier for farm workers and domestic servants in New Zealand to slip into casual conversation with their employers than in England.[37] Similarly, although some run-holders supervised the men but did not engage in manual labor themselves, many others worked alongside their men at such jobs as mustering and running the animals through the sheep dip. In this respect they had more in common with the American rancher than with the English country gentleman.[38]

As upward mobility slowed, however, social lines hardened, such that as the century wore on it probably became less acceptable for workers to converse casually with their employers. The relations among classes likewise became marked by varying degrees of tension.[39] The explicit focus of hostility included such bread-and-butter matters as wages, working conditions, and the availability of land, but the question of egalitarianism and hierarchy—or social standing and honor—was another major grievance. A theme of the political speeches of the spokesmen for the labor movement late in the century was the “dignity of labor”[40] —an expression of anger over the pretensions of the employer and the well-to-do and the subservience of working people, in part.

Farmers as a rule sided with the large landholders and other members of “the capitalist classes” when it came to issues concerning working people. Generally opposed to labor actions, farmers sided with the “capitalists” in the traumatic Maritime Strike of 1890, for example. When the strike reached the port town of Timaru, a number of farmers in the district expressed a willingness to send both teams and men to the harbor to do the work of the strikers “as a practical protest against the strike.”[41]

The strongest hostilities, though, were expressed by both workers and farmers toward the large landholders, over the explicit issue of land. By the end of the 1850s all the usable land in both Canterbury

and Otago had been taken up, the vast majority of it by squatters who held leasehold rights from the Crown.[42] Anyone who wanted land was confronted by a phalanx of run-holders determined to protect their investments. In turn, the run-holders felt threatened by the persistent efforts on the part of their social and economic inferiors (and of one another as well) to acquire the most valuable and productive portions of their estates. Very little land was acquired as freehold initially, so the squatters' concern was not irrational: anyone with the capital could attempt to buy any part of the propertyholders' leasehold from under them.

Disagreements with the run-holders over land policy was manifest within the Canterbury provincial council as early as the mid 1850s.[43] By the 1860s the run-holders dominated the council, and they proceeded to pass legislation that protected their interests by making it difficult for people of limited means to acquire small farms.[44] Although the Otago run-holders apparently were not as powerful as the Canterbury pastoralists in provincial politics, the same antagonism between pastoralists and agriculturalists was manifest there as well.[45]

In the 1870s a land boom was under way in Canterbury. Land agents with the necessary capital managed to purchase large sections of runs in advance of the farmers' demand, and many of these speculators apparently made handsome profits. As a result, some of the hostility that people felt toward the large landholders was redirected toward the land agents. The seventies land boom spurred a large number of squatters on the plains, where the demand for farms was particularly high, to buy their land from the Crown as a defensive move; these purchases, together with the many small farms that were bought during that decade, meant that by the end of the 1870s virtually all the comparatively flat and fertile portions of Canterbury had been acquired as freehold. Remaining in leasehold were chiefly the higher and less desirable runs, those not in great jeopardy of purchase by land agents or small farmers.[46]

The hostility that many people felt toward the large pastoralists grew intense during the depression of the 1880s and 1890s.[47] It was now hard enough for the working man to find a job, let alone acquire a farm;[48] and the well-to-do seemed to take advantage of the workers by lowering wages and cutting costs to such an extent that working conditions became unbearable. The colony as a whole was suffering

from economic malaise, and the run-holders by and large were blamed.

Refrigeration and Farming

In 1882, a technological development occurred that changed the economic fortune of New Zealand and fundamentally altered the relationship between squatter and cockatoo. This was the invention of refrigerated shipping, whereby sheep carcasses could be frozen and transported to Britain for sale at the local butcher shop. Now, miraculously, the meat was at least as valuable as the fleece. Within a few years—by the late 1880s—a number of freezing works (where livestock are slaughtered, dressed, and frozen) were constructed near the leading ports, a small fleet of refrigerated ships was fitted out, and the new industry was in business.[49]

Refrigeration revolutionized not only the sheep industry in New Zealand but dairying as well, in that butter and cheese could now become profitable export items. Refrigerated shipping therefore resulted eventually in a very substantial increase in dairy farming, along with the development of a complex of cooperative dairy factories throughout rural New Zealand.[50] Yet the dairy industry grew more slowly than the refrigerated meat industry, for it did not come into its own until well after the turn of the century. What is more, dairying was—and still is—more important in North than South Island. Sheep remained the preeminent livestock type in Canterbury and Otago, although some dairy farming became mixed with other agriculture in the more suitable areas, such as around Christchurch.[51]

Refrigerated shipping provided alternative avenues of upward mobility for the working man and for the small farmer, and eventually it resulted in a large increase in middle-class farmers and a relative decline in the number of working people. In the case of dairying, the work was hard and the hours long, but the ambitious and energetic laborer did not need much capital to begin. I do not focus here on dairy farming, however, because dairying never became very important in the region of my research. I focus rather on sheep production, a type of farming that required greater capital resources

for the beginner than dairying, but that was still within the reach of at least some working people.

Another crucial development that came about at nearly the same time as refrigerated shipping was a return of prosperity, beginning in 1896 and continuing until 1921. Land could be expensive and hard to find, and not all who tried managed to improve their lot, but in general the economic prospects were good for those who could acquire farms or who already had them.

To raise sheep for the carcass as well as the wool required a very different kind of operation from that of the sheep runs, a fact that seems to have favored the development of the small, family farm. The story is complicated; let me begin with a description of the changes required by the new form of production.

First, the frozen meat industry strongly favored other breeds of sheep than the merino.[52] Among the most popular were the Romney, Border Leicester, and Corriedale, which produce less wool of lower quality than the merino, but better meat, and which are also more docile and easier to deal with—an important consideration, since the new industry required that the sheep be handled rather extensively. These breeds also produce more lambs on average, and thus more carcasses per unit of time.

These other breeds have a drawback, however, in that they need exotic grasses to thrive. This leads to the second change required in the new form of sheep production: the landholder had no choice but to plant permanent pasture (an enormous job if the land was still in the native tussock). However—and here is the third point—the new type of sheep farm could be much smaller than a run. Not only did the permanent pasture support more sheep per acre, but each sheep produced more income because its value included earnings from both the wool and the carcass. Whereas a viable sheep run had to be several thousand acres, a profitable sheep farm did not have to be more than several hundred.

A fourth difference was that the new type of sheep farming was much more labor intensive than run-holding. The farmer not only had to plant permanent pasture; he also had to build fences to reduce the size of the paddocks for better stock management, and he had to move the sheep from one paddock to another occasionally to get the most value from the exotic grasses (on sheep runs the sheep were moved but a few times a year at most). Because pasture grasses grow

very little in winter, supplementary winter feed (usually turnips or swedes) had to be planted; moreover, crop rotation was considered advisable, so if possible the pasture grasses were periodically replaced by such crops as corn or wheat. The new breeds of sheep themselves required greater care as well. For example, since they generally had more difficulty than the merino in lambing, the ewes had to be watched closely and assisted at lambing time.

I have mentioned that wheat farming was not equally suitable for all parts of New Zealand; the same was true of the new sheep farming. Just as the exotic grasses did best at lower altitudes where the growing season was longer, the breeds of sheep that the new meat industry sought were less hardy than the merino and did not fare as well in higher, rougher country. As a result, sheep farming became concentrated chiefly in the same areas that experienced the wheat boom, that is, at lower elevations and in flatter areas, whereas runholding continued relatively unchanged in the other regions. In the case of Canterbury and Otago, sheep farming became dominant on the alluvial shelf bordering the ocean and in the lower valleys extending into the foothills; sheep runs, in contrast, remained dominant in the higher foothills and lower mountains (to elevations as high as the merino could survive) and in the higher, colder valleys of Central Otago and South Canterbury.

The economics of run-holding was also changing on account of the frozen meat industry. The merino carcass was worth much less than that of the Border Leicester or Romney, but it was worth something, and while most of the run-holder's income came from the sale of wool, it was now possible to augment that sum by selling the animals themselves. Hence the run no longer had to be quite as large as before to be profitable (though it still had to be counted in the thousands, and not the hundreds, of acres), because each animal produced a slightly higher income for its owner.

Refrigerated shipping, then, did not eliminate the distinction between farmers and run-holders, for now two rather different kinds of sheep raising coexisted. One, sheep farming, was a variety of intensive agriculture, for it involved the use of agricultural equipment to work the soil. The people who engaged in this production were cockies; their farms were labor intensive, they required only a few hundred acres to support their families, and their incomes came from the sale of both meat and wool. The other form, run-holding,

was a continuation of extensive pastoralism, inasmuch as the flock consisted of merinos that were fed on tussock. Agricultural equipment played a minor role in the run's operation, which was not labor intensive. A minimum of several thousand acres were needed to support a family. And a large majority of the run-holder's income came from the sale of wool.

A “Revolution” in Politics

The development of intensive sheep farming was accompanied by major changes in the stratificational pattern or class structure of New Zealand, for as the new sheep farms multiplied, the large estates were breaking up. This situation involves both myth and fact. Beginning in the 1890s and continuing today, these events have occupied a central place in the country's national ideology: according to popular thought, the New Zealanders stood up to land monopoly, economic inequality, and social injustice and brought forth a more egalitarian order. Yet much of the story is true. Certainly the size and number of large properties in New Zealand declined substantially in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many large landholders left the colony altogether, and others presumably sold all or part of their holdings and put the money to other uses.[53] Although the “gentry” did not disappear entirely, by 1917 their ranks had been thinned considerably, and the ones who remained no longer enjoyed as high a position in the social order.[54]

One popular explanation for these developments locates the cause in the parliamentary election of December 1890, when the first Liberal majority was voted into office.[55] By that time the colony had suffered over a decade of heavy depression, and the votes of working people, farmers, and the urban middle class together forced out of office the protectors of “the moneyed classes” and installed a government more responsive to “the people.” A major part of the Liberal government's political program was land legislation that (it was hoped) would bring an end to land monopoly. First, the government instituted a “bursting-up tax” that fell more heavily on the large landholders than others; second, it passed an act enabling the state to buy large estates at a fair price (whether the owners consented or not) and subdivide them into smaller holdings for sale to settlers;

and third, it instituted a system of loans to assist working people in the purchase of farms. The popular image at the time, then, was that the government itself had caused the demise of the large estates.[56]

This explanation is somewhat in doubt, however, because at the same time a variety of economic forces were also at work to end the squatter system.[57] For one, there was a rise in land values. The agricultural recovery after 1896 created a demand for farms, which increased the price of land, in turn stimulating the owners of large properties to subdivide and sell. At work here was the profit motive, not government policy. Yet one part of the Liberal land legislation may well have been a factor in the breakup of the estates: namely, the policy of cheap government loans, which enabled people with little capital to acquire land.[58] Another significant force was that the new sheep farming was better suited to small, family farms than to large-scale operations. Because labor was relatively expensive, especially with the return of prosperity after 1896, workers' wages cut deeply into profits, whereas the labor of family members was cheap. Large-scale, intensive sheep farming may also have involved insurmountable management problems that were not an issue on the family farm. Nonetheless, one historian, Stevan Eldred-Grigg, suggests that these economic explanations are not sufficient. The main reason the large landholders sold their property, he argues, was that they were frightened by the political rhetoric of the day, a rhetoric that labeled them enemies and called for such radical measures as land nationalization. Thus, many of the large pastoralists simply cut their losses and left for Europe and elsewhere, or at least got out of the business of run-holding.[59]

Some pastoralists became farmers, subdividing their properties but retaining significant portions for themselves; they were therefore in a position to make large profits when agricultural prosperity returned. Others, who held property in areas unsuitable for farming, perhaps continued as run-holders. Generally these pastoralists were not the wealthiest of the large landholders, however, because sheep raising was riskier and less profitable in those locales. What is more, their properties too were subdivided, though instead of being converted into small farms they were cut up into medium-sized runs. The property held by a single family in the nineteenth century was occupied by several in 1920. Not only did the remaining run-holders now have less land, but they were surrounded by newcomers, most of whom were joining the ranks of the pastoralists for the first time.

A Return of Prosperity.

The period from the late 1890s to 1921 has been called the golden age of New Zealand farming, for it was a time of agrarian prosperity:[60] agricultural products now brought sufficiently high prices that the farmer made a very good living, farming expanded to the point that it replaced run-holding as the major form of land use, upward mobility resumed (at least for a time), and the cocky rose to a position of dominance in New Zealand's economic and political order. These developments in turn eventuated marked changes in the stratificational system.

We have already seen one of these changes: the gradual breakup of the estates. The possession of a large sheep run was no longer as clear a sign of elite standing as it had been. Moreover, the pastoralists no longer enjoyed political dominance to the degree they did before the “revolution” of the 1890s.[61] Yet few working men held positions of genuine political significance either, for by 1893 power had shifted to the middle classes, and particularly to the farmers.[62] Now the voice of the cocky was most audible in public affairs.

Life-style continued to distance the well-to-do from those below them during this period, however. Many better-off families could still hire large numbers of servants, for example, and the exclusive social life of visiting, hunting, and the like did not cease.[63] An equally significant feature that set the economic and social elite apart was the way they educated their children. Some undoubtedly sent their sons and perhaps daughters “Home” (to England) for a public school education, but New Zealand also had its own well-developed and highly respectable system of private boarding schools.[64]

The growth of the farmer's political importance occurred in the context of the agricultural recovery, but prosperity was not the sole cause of this political development, which, as we have seen, was apparent already in the election of 1893, when the colony was still deep in depression. While the agricultural recovery enhanced the farmer's position, the growth of refrigerated shipping was equally important, for it stimulated intensive agriculture, which by 1914 had outstripped extensive pastoralism in the economy.[65] An increase in the export of meat and dairy products came about because the number of farmers increased; this could take place only because the amount of land devoted to extensive pastoralism, as well as the ratio of pastoralists to farmers, was declining.

The upswing in agricultural prices during the 1890s brought renewed upward mobility. Established farmers increased their holdings, and working people acquired small properties of their own, which in some cases they were able to enlarge over the next several years. The recovery of the 1890s to the 1920s had another positive effect, in that the farmers now felt very prosperous (assuming, of course, that the price they paid for land was not so high that their mortgage payments were a severe burden). Indeed, it has been suggested that, during the teens, the New Zealand cocky was the most affluent farmer in the world.[66] By the 1920s probably as many farmers as run-holders lived in homes with maids' quarters, and the exclusive boarding schools may have enrolled more children of farmers than of run-holders.