| • | • | • |

Alevis and Sunnis: Separate Spaces in a Shared World

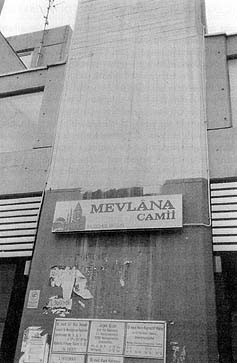

The migrant diaspora context does little to alleviate the already deep-set antagonisms, suspicion, and animosity between Sunnis and Alevis. In fact, if anything, many Sunnis become still more hostile toward Alevis. The unchecked politicization of mosque-centered religious preaching that proliferates in Germany is often directed against infidel immoral Germans, communists, and, by extension, Alevis. Abroad, located as they are in an environment that is characterized as haram, it is easy for anti-Alevi Sunnis to make the association that these heretical Muslims would not only join forces with Germans of the political left but adopt German moral codes as well. Berlin supports dozens of mosques, which focus sectarian identity. The Mevlâna mosque (fig. 30), for example, is located in a modern Berlin-style high-rise, shared with numerous doctors’ practices and residential apartments. Named for the Mevlevi dervish order founded by Jalal ud-din Rumi, a medieval Persian poet who settled in Konya, this mosque is associated with Sufi devotional practices. The signboard depicts Rumi’s mausoleum in Konya.

Figure 30. Concrete apartment/office block with names of residents (several doctors’ practices) and the Mevlâna Camii mosque, Berlin. Photograph by Ruth Mandel.

The Sunnis and Alevis generally live and operate in very different social circles. It is rare for individual Sunnis to be invited to an Alevi wedding or circumcision celebration—or vice versa. When a Sunni friend of mine in Berlin was asked by an Alevi friend and neighbor to be the kivre (circumcision sponsor; godfather) of his son, the novelty generated quite a bit of gossip. Alevis try to do as much business as possible at Alevi-owned establishments, a preference reinforced by regional identity for both Alevis and Sunnis. In Berlin in 1990, for example, a large group of Alevi families collectively pooled their resources in order to open a private wholesale store. Some claimed that they had been excluded from similar Sunni-owned ventures and therefore wanted their own. Both in Istanbul and in Berlin, I often was astonished at the extent and intricacy of how the Alevi networks functioned. Particularly in Turkey, since Alevis are the minority group, they are more sensitive than Sunnis to the subtle clues and signs that indicate who is who.

Alevis may conceal their identity, as did Haydar, a young Alevi man from eastern Turkey in trying to appeal to Sunni customers in his video shop. In 1985, approximately seventy Turkish video rental shops in West Berlin catered to tens of thousands of clients demanding new films several times a week.[9] At Haydar’s shop, the clientele ranged from young children not tall enough to reach the counter to fatigued working people on the way home from work to single young people congregating to socialize. Relatives and friends of the shop’s owner often dropped in, including several young male cousins and their friends, who would sit in the shop learning to play the lutelike saz, associated with Alevi mystical poetry, under Haydar’s tutelage. At times when he had to work at a second job, his wife, Havva, ran the store.

During the Şeker Bayrami holiday (celebrated at the end of Ramadan), Haydar had a bowl of the conventional candies to give to customers, as well as limon kolonyasi (lemon cologne) to squirt on their hands.[10] Although Haydar offered me some candy, he and his cousins refused to partake of it, his nephew explaining, “We don’t celebrate it—it’s not our holiday. Kurds don’t observe Şeker Bayrami.” When I asked, he admitted that he had meant Alevis, not Kurds. Perhaps he thought that I, a foreigner, might know what Kurds were but not Alevis.[11] He may have been testing me; or, he may have preferred not to implicate himself and his relatives as Alevis.

The very act of providing Bayram candy for Sunni customers was telling. Not only would it please them, it was a good business practice. Consonant with the Alevi practice of dissimulation, Haydar could “act” Sunni; he feared that had he not tried to “pass,” he might have lost customers, who would have taken their business to a Sunni.