| • | • | • |

A New Pedagogy of the Incarcerated

Acting through the principle of freedom of worship, Islam meets these conditions and shows a remarkable capacity to redefine the conditions of incarceration. A new Muslim repeats the attestation of faith, the shahada, before witnesses at the mosque. His Islamic identity then means a fresh start, symbolized by the choice of a new name, modifications in his physical appearance, and an emphasis on prayer. He is linked to his Muslim brothers worldwide, as suggested by frequent representations of Mecca in the mosque’s decor, for example in the mosque shown in figure 25 above. More immediately, he is linked to his fellow Muslim prisoners. Inmates like those at Masjid Sankore, thanks to communal prayer, qur’anic and Arabic scholarship, and invocation of shar‘ia have been able to exercise significant group control over their fellows. Historically, Christian prison reformers envisioned conversion as cloistered reflection or silent prayer. Islamic teaching, however, changes self-image and social relationships primarily through communal prayer and qur’anic recitation, which establish ties of identification and action between the Muslim believers and the sacred texts of the Qur’an and Sunna. Through religious practice,[6] the prisoner distances himself from the outside world, conceptualized as dar al-harb, and migrates (hijra) toward the ideal of dar al-Islam, defined not by territory but by Islamic practice. The greater the capacity of the prison jama‘a (congregation) to establish the privilege of congregational prayer, the greater the potential effect upon the individual Muslim. It is an impressive sight to see 50 or 100 prisoners bowing and kneeling in prayer in the middle of a prison exercise yard or in a room isolated within a maze of corridors and cells, as in figure 24, above. Since 1973, after consulting the Islamic Center in New York, DOCS has recognized four holidays: Hijra (New Year’s Day), Maulid al-nabi (the Prophet’s birthday), ‘Id al-fitr (feast commemorating the end of the Ramadan fast), and ‘Id al-adha (feast of the sacrifice). During the Ramadan fast, Muslims can requisition halal meat and are permitted to use the kitchen to prepare iftar meals. For breaking the fast, they are also permitted exceptionally to take some of the food back to their cells.

The Muslim’s cell can be recognized by the absence of photographic images and the otherwise ubiquitous centerfold pinups of naked women. When a man becomes a shahada (convert), he gradually learns the proper etiquette for a Muslim inmate. To reorganized personal space corresponds a changed attitude toward his body for the new Muslim. He tries to avoid pork and other non-halal foods; some prisoners even object to the use of utensils that have touched forbidden foods. The issue of providing halal diets to Muslim prisoners in New York State has been in litigation for many years, with the state now using the excuse of budgetary constraints to refuse. The convert also becomes concerned with wuzu (ablution), here transformed into a code of personal cleanliness and grooming. In addition to their kufa (skullcaps), beards, and djellabah (long shirts), the Muslims are usually well scrubbed, and, as advised in the orientation booklet, often wear aromatic oils when entering the mosque. The use of personal toiletries defines the Muslim’s body as different from the sweaty, disciplined body of the ordinary prisoner. Cigarette smoking is also frowned upon among orthodox Muslims.

In respect to a prisoner’s repressed sexual desire, the Islamic regime acquires double significance in its strict opposition to homosexuality. Certainly, it upholds qur’anic injunctions and encourages the sublimation of desire into a rigorous program of study and prayer. More subtly, however, a man’s adherence to these injunctions illustrates counterdisciplinary resistance to one of the more overt dominance hierarchies encountered in prison life. Sexual possession, domination, and submission represent forms of “hard currency” in prison. Thus by asserting the distinction between halal and haram, between what is permitted and what is forbidden, the Muslim community simultaneously follows Islamic law and negates one of the defining characteristics of prison life.

The most contentious issue regarding the prisoner’s body involves surveillance and personal modesty. For example, during the 1970s, the Prison Committee worked with the state to arrange special times for Muslims to shower as a way to ensure privacy. Eventually, DOCS designated Thursday nights for Muslims to coordinate showers among themselves. A related yet unresolved issue is the “strip search,” when men are forced to strip naked and submit to an inspection of their body cavities. Many prisoners refuse to undergo this procedure. Consequently, they file grievances, risk being “written up,” sent to the “hole,” or even beaten if they refuse too vehemently. Lawsuits have been filed, but the courts have backed up the wardens, who insist that security issues take precedence over freedom of religious expression.[7]

The Muslim community generates a certain degree of physical, emotional, and even biological relief from the grinding prison discipline. This extraordinarily synthetic capacity to alter the cognitive patterns of an inmate’s world may even carry over into the realm of taste (halal diet), sight (reverse-direction Arabic script, calligraphy, absence of images, geometrical patterns, etc.), and smell (aromatic oils, incense). By staking out an Islamic space and filling it with a universe of alternative sensations, names, and even a different alphabet, the prison jama‘a establishes the conditions for a relative transformation of the most dreaded aspect of detention—the duration of one’s sentence, the “terror of time.” No other popular inmate association has proved itself capable of redefining the prison sentence in such a long-term way, for in its most successful manifestation, Islam has the power to reinterpret the notion of “doing time” into the activity of “following the Sunna of the Prophet Muhammad.”[8] Prisoners spend much of their time engaged in qur’anic study, conducted according to a nationwide curriculum, moving through various levels from elementary instruction in beliefs and behavior (‘aqida and adab) to advanced scholarship in law, qur’anic commentary, and theology (fiqh,tafsir, and kalaam). There is even a course in leadership training to prepare prisoners for their roles as imams in other jails or on the street.

Materials for these classes, including cassette and video tapes and books, were initially donated by concerned Muslim organizations, but for the past ten years, Muslim inmates themselves have earned surprisingly large amounts of cash through their monopoly of the distribution and sale of aromatic oils, incense, and personal toiletries throughout the prison system. These funds are also used for the elaborate carpentry and calligraphic painting that is done in their mosques, as well as for the catering of ritual feasts for the Muslim ‘Id-al fitr and ‘Id al-adha holidays. They contribute to the sponsorship of intramural cultural events, which are often staged for the purpose of da‘wa. Sankore even published a critically acclaimed newsletter, Al-Mujaddid (The Reformer), which has found its way to important readers throughout the Muslim world sparking international concern for Sankore’s inmates, as well as donations in the form of Qur’ans and other literature, from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Pakistan. Sheikhs, diplomats, and other emissaries from Muslim countries traveled to Green Haven to visit Sankore. Even the late Rabbi Meir Kahane, founder of the Jewish Defense League, met with Green Haven’s Muslim community to thank them for the hospitality extended to a Jewish inmate who was welcomed to conduct Hebrew prayers in a corner of the mosque after being ostracized by his own synagogue. The prison mosque is not only the center of religious instruction but also serves as an alternate focus of authority within the prison. Its power is determined mainly by its large membership, who legitimize the influence of their chosen leaders with respect to the larger inmate hierarchy, encompassing representatives of powerful ethnic gangs such as the Mafia and the Chinese triads, or white fascist parties such as the Aryan Brotherhood and the Ku Klux Klan.[9] For example, in the late 1970s, Sankore’s inmate imam was Rasul Abdullah Sulaiman, who came to prison already possessing some of Malcolm X’s charisma because he had been a prominent member of the latter’s entourage. He quickly rose to such a powerful position within the prison that he had his own telephone and traveled around the place at will, accompanied by a corps of surly bodyguards. He arranged the visits of outside Muslim dignitaries, brought family and friends of the prisoners into the masjid for prayer every Friday, and reportedly even constructed a network of small bunks inside the mosque for conjugal visits after jum‘a (Friday prayer).[10]

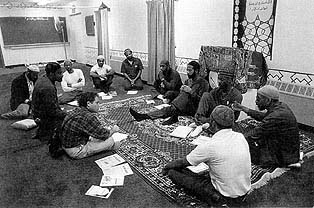

This was the period when Sankore achieved its reputation as the most important center for Islamic da‘wa in America. Before his release in 1980, Rasul married the mother of a fellow inmate, and his new “stepson” was elected imam. This union resulted in the effective and orderly transition of power in the mosque after Rasul’s release on parole. “Sheiks” who study tafsir, fiqh and Hadith, moreover, use these skills to play a role in councils (majlis) to resolve conflicts and keep the peace (fig. 27). They challenge the secular jailhouse standard of status based on physical strength or a manipulative intellect.

Figure 27. The Majlis ash-Shura, or high council, of Masjid Sankore at Green Haven Correctional Facility, N.Y., with the author, 1988. Photograph by Jolie Stahl.

It is possible to explore the deeper implications of the Islamic pedagogy of African-American prisoners if we look at the process of Islamization as a negotiation between the prison authorities and the Muslim inmates where the state’s logic of institutional order meets the fundamentalist doctrine of Pax Islamica, according to which the world consists of only two domains, the dar al-Islam, literally, the House of Peace, and the dar al-harb, the House of War, which is identical with non-Muslim territory. The reorientation and purification of personal space is made possible for the Muslim prisoner through a serious counterdisciplinary regime. Once he is known as a Muslim, the prisoner has little choice but to follow this new set of rules or else he risks at least the disapprobation of his fellow inmates and possibly a physical lashing. Non-Muslims who have been around long enough to understand the alternative set of rules will even admonish the novice convert (mubari) if he is derelict in performance of his obligations.

As enforced by the incarcerated community in general, the shar‘ia becomes an autonomous self-correcting process administered by and for Muslims. “A Muslim’s blood is sacred. We will not allow anyone to shed a Muslim’s blood without retaliation. The prison population knows this and would prefer for us to handle our situation.”[11] So widespread is the fierce reputation of the incarcerated Muslim that the most ruthless urban drug dealers carefully avoid harming any Muslim man, woman, or child lest they face extreme prejudice during their inevitable prison terms.

If this capacity to purify and control Islamic space is remarkable in its consistency, it is not without problems. Inmates may come to Islam merely for protection, not to find a new life. Or they may mistakenly believe that they can absolve past misdeeds and change themselves simply by changing their names and reciting the kalima shahada. They then give the outward appearance of devotion but end up returning to prison having committed the same crimes. Generally, however, low recidivism rates and success in the rehabilitation of drug and alcohol addiction, win tolerance, even approval, for Muslims (Caldwell 1966).

The numbers of practicing Muslims remain significant and their influence continues to rise among the transient populations who fluctuate between prison and the devastated streets of America’s urban ghettos. This calls to mind a comment to the effect that all African-American youths have at least some familiarity with Islam, either through a personal encounter, a relative, a friend, a fashionable item of apparel, or, as is more frequently the case today, in the form of rap music poems.[12] Islam constitutes a cultural passport, whose bearer may exercise the option to depart the anomic zone of ghetto life for destinations mapped out by the Qur’an and Sunna. Nowhere is this option more evident than inside a maximum security prison, where the literal interpretation of the Prophet’s hijra functions as a utopian itinerary and an alternative vision of truth and justice. It insulates the prisoner against the dulling experience of incarceration by inducing him to a regime of five daily exercises (salāt), consisting of a series of obligatory prostrations, that not only transforms the physical relationship to his immediate personal space but also restructures time according to a daily, weekly, and annual calendar of rites that correspond neither with the prison nor with American society at large.

In this sense, Islamic pedagogy has an invigorating effect upon the prison convert. The Qur’an becomes his instructional manual of counterdiscipline. Its study opens more than new scriptural potentials and interpretive traditions, more than simply a new grammar, phonetics, and vocabulary (Arabic), but also an impenetrable code whose messages elude all but the most devout. As a consequence, this counterculture is not simply a ritual of distraction but an ontological reconstruction occurring within a well-defined space, dar al-Islam, characterized by a common set of sensory values evident in smell (aromatic oils, incense); sight (elimination of literal and plastic art forms, elevation of figurative and stylized forms); sound (qur’anic recitation), taste (halal diet) and touch (promotion of strict interpersonal modesty). New intellectual values focus upon the Islamic sciences, particularly fiqh, and new ideas about geopolitics and history from an Islamic perspective.

These values have compelled many African-Americans to review traditional interpretations of their ethno-history, literature, and folklore. Through the prism of Islam, the African-American Muslim invokes a new hermeneutic of power: historically captured, enslaved, and transported to the New World, then miseducated and forced to live an inferior existence, the African-American must enshrine powerlessness even in the act of remembrance, celebration of, or reverence for his ancestors. But his conversion to Islam adds new dimensions to that history, particularly as it emphasizes the presence of African Muslims and nonslave populations, as well as evidence of resistance to Christianization.

Islam symbolizes the aggregate value of authentic African-American culture. In the past, dance, music, fashion, narrative, and even certain forms of Christianity (e.g., Afro-Baptism) have served to mediate, if not transcend, social, racial, and economic oppression. As revealed through the experience of prison da‘wa, Islamic discipline has the power to effect this ontological transformation through a series of counterdisciplinary measures. In terms of social relations, Islam teaches that those who lack the power to transform their material conditions need only reflect upon the ideal qur’anic past in order to see themselves as contemporary actors in a world whose rules of social distinction are neither tangible nor fixed unless they are divine. In this way, Islam deals with class, ethnic, and racial differences—even those as widely divergent as between freedom and incarceration—by collapsing the past, the present, and the future into a simultaneity of space and identity. To the extent that Islam succeeds in America’s prisons, it offers a closed but definitive response to the modern dilemma of justice in an unjust world.

By instituting a strict code of behavior and by networking with other prisoners, the Sunni Muslims established a unique identity. While they are predominantly African-American in membership, there are now a few Arabic- or Urdu-speaking prisoners, and more recently a handful of Senegalese Muslims. Green Haven today, however, as noted above, is divided between two mosques, Sankore and ut-Taubah. The Muslims at ut-Taubah have pledged bay‘a to Warith D. Muhammed, whose imams are always the civilian chaplains appointed by DOCS.

In Attica Prison, the Muslim communities united in 1985 under the aegis of a strong Sunni presence, but there, too, the administration is seen as fomenting disputes, and the community remains unstable because of ongoing differences between Sunnis and members of Farrakhan’s resuscitated Nation of Islam. The Sunni Muslims, who labored to unify Islam under a homogeneous practice, are seeing their space fission once again. “The Nation of Islam has recently been restructured and separated from the Sunni community.…There are approximately three hundred Muslims in the facility” (Rahman 1989). Less than twenty-five miles from Attica at Wende Correctional Facility, similar issues plagued the unified jama‘a (Raheem 1991).[13]

For all these problems, the goal has always been to create a territory that is neither “of the prison” nor “of the street” but a “world unto itself” defined by the representational space that is common to Muslims worldwide. The profundity of this spatial vision is evident in the metaphor, quoted in the title above, used by one prisoner serving a 25-years-to-life sentence: “In here the Muslims are an island in a sea of ignorance.” Islam’s attraction for prisoners lies in its power to transcend the material and often brutally inhuman conditions of prison. Although it may seem to some just another jailhouse mirage, the Muslim prisoner sees entry into that space as a miracle of rebirth, and one that may even spread from the prison to the street.