| • | • | • |

Masjid Sankore: “Medina” for New York’s Prisons

Founded in 1968, Masjid Sankore became the first recognized Islamic institution in a New York prison. Its founders were several African-American converts who in the late 1960s collectively sought assistance from Muslims outside the prison in a crusade to ameliorate their conditions of worship. They turned particularly to the leaders of Brooklyn’s indigenous Dar ul-Islam movement, who soon were making regular visits and offering assistance in negotiating with the prison administration, as well as with the outside world. Eventually, the Muslims won the warden’s approval to establish a permanent prayer hall and named their mosque after an ancient African center of Islamic teaching in Timbuktu, Mali.

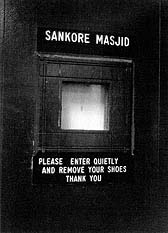

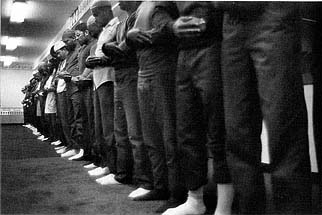

Sankore rapidly outgrew its initial cramped space, eventually taking over the prison’s old tailor shop, a comparatively spacious area with real pillars. The prisoners devoted much time and effort organizing the space into a genuine masjid and a place of refuge from the drab confines of the rest of the prison. “When you walked in there, it was another world. You didn’t feel like you were in Green Haven in a maximum security prison. Officers [guards] never came in. It was like going into any other masjid on the outside; you felt at home,” commented Sheikh Ismail Abdul Raheem, one of the first emissaries from the “Dar” movement to visit Sankore. The door to the mosque announced a transition to a different space (fig. 23). Once inside, it provided space for quiet, interaction, and, above all, communal prayer (fig. 24).

Figure 23. Door to Masjid Sankore at Green Haven Correctional Facility, N.Y. Photograph by Jolie Stahl.

Figure 24. Friday prayers at Masjid Sankore, Green Haven Correctional Facility, N.Y. Photograph by Jolie Stahl.

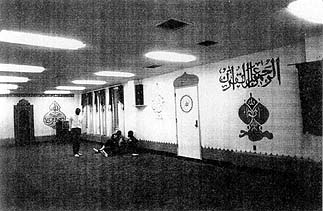

Sheikh Ismail also recalled that, in the early years, both the Sunni Muslims and the Black Muslims (Nation of Islam) practiced a cadenced march through the corridors as if to mark out their own militant counterdisciplinary tradition. That was the only thing they shared, however. The Nation sought and demanded its own mosque, which after 1976 became the American Muslim Mission Mosque (fig. 25), known as the Masjid ut Taubah (the Mosque of Repentance). Today, the American Muslim Mission and the Nation of Islam compete fiercely with the Sunnis for new initiates at Green Haven. Because of official policy, life-sentence prisoners as well as those viewed as potentially disruptive to the prison regime are transferred every few years in and out of the ten different maximum security prisons in the state. Thus as time went on, alumni of Sankore spread their Islamic fervor throughout the correctional system. Simultaneously, the Nation of Islam and orthodox Sunni groups like the Dar ul-Islam Movement won further concessions on behalf of Muslim inmates. In these negotiations with authorities, the Dar’s “Prison Committee” used Masjid Sankore as the standard against which Islamic religious freedom in prison was measured.

Figure 25. The American Muslim Mission mosque, the Masjid ut-Taubah, in Green Haven Correctional Facility, N.Y. Photograph by Jolie Stahl.

By 1972, the official status of Muslim inmates was further enhanced by the role they had played during the bloody Attica uprising of the previous autumn. Contrary to their image as militant radicals, the Muslims in Attica protected their guards and used their power as a disciplined, self-governing inmate organization to reestablish order during a period where the entire prison society was threatened with permanent anarchy. For the first time in history, inmates formed a disciplined syndicate, visibly identifiable by their prayer caps (kufa) and manicured beards, whose outlook was linked neither to the old criminal subculture nor to the rebellious militant ideologies of the epoch. Consequently, the embattled Department of Corrections offered them a modicum of legitimacy and surrendered some of its own power to govern the prison in a tacit alliance with the Muslims.

Following the Attica riot, DOCS designated Green Haven, the scene of similarly explosive tensions, a “program facility,” where emphasis was placed on learning and rehabilitation as opposed to punishment. College courses, vocational training, substance-abuse programs, work release, and family-reunion visits resulted directly from a negotiation of inmate demands and the actions of newly appointed liberal administrators. Muslims were situated at the center of these activities and forced the administration to submit to literal interpretations of laws pertinent to religious freedom for prisoners. During this period, they asserted the right to perform daily salāt, and they even achieved relative financial autonomy by importing and selling legal commodities from the outside. Masjid Sankore instituted classes in qur’anic instruction and Arabic. Prisoners throughout the state referred to Green Haven’s masjid as the “Medina” of the system—a place of hijra in the sense of retreat, refuge, and reconstruction. According to records from the Islamic Center, Sankore had more converts to Islam than any other mosque in America during the years 1975 and 1976. Some of the converts were outside guests or even corrections personnel, who would often volunteer to work Sankore religious events without pay (Mustafa et al. 1989). Other successful prison mosques were eventually started in Attica, Auburn, Clinton, Comstock, Elmira, Napanoch, Ossining, Shawangunk, and Wende. A family reunion visit at Wende is shown in figure 26.

Figure 26. Shu’aib Adbur Raheem, a former imam of Masjid Sankore, and his wife during a family reunion visit at Wende Correctional Facility, N.Y. Photograph by Jolie Stahl.