| • | • | • |

The Gendered Politics of Representation in a Multicultural Context

Feminists have long argued that collective identities are androcentric. Julia Kristeva (1989), for example, argues that collective identities are produced along a logic of masculine identity formation that includes rejection of some “other” and stresses the control, if not the suppression, of differences within.[7] As far as Western cultures are concerned, many feminist analysts have expressed their suspicion of “substitutionalist universalism,” inasmuch as they detect male, middle-class, white men profiled behind the equal individual of democratic discourse (Benhabib 1986; Fraser 1989; Love 1991). Similarly, the case for the androcentric mold of the Islamic ummah has been made repeatedly by Muslim feminist scholars (Abrous 1989; Ait Sabbah 1986; Jowkar 1986; Lazreg 1988; Mernissi 1983, 1987). This argument is at the core of my understanding of the gendered politics of representation as illustrated in the male public debate about female attire.

In this case, deterritorialization brought about by Maghrebi postcolonial immigration raises the problems of the cultural reproduction of identity and values, not only for Maghrebis facing possible gallicization, but also, I would argue, for the French, whose territory now contains “strange foreigners,” to paraphrase Kristeva (1989: 274–77). Because of the gendered dynamics of collective identity, deterritorialization has specific consequences for both French and Maghrebi men, as male vehemence during the affair of the veil so aptly demonstrates.

The affair challenged patriarchal and fratriarchal understandings of gender roles and identities. In this particular instance, Maghrebi fathers and religious hierarchies were joined by Catholic and Jewish clerics who demonstrated unreserved support for the veil. Together they opposed the free circulation of women in the fraternal and secular French Republic. Those among the second-generation Beurs hoping to join the French fraternity (such as Arezki Dahmani of France-Plus), however, supported a strict interpretation of secularity. Others, less confident of their place in France or more involved in a process of ethnicization, defensively supported the veil and their right to “difference” in protecting “their women.” For them, Islam has become the main resource and guarantor of a marginalized and ethnicized androcentric collective identity (Bloul 1992), and Muslim women have become the privileged site for the affirmation and display of such identity, quite apart from any individual decision women may make. Frenchmen’s responses betray their understanding of this collective use of women. As Qsarstadt and Qsarheim men are also well aware, the existence of “veiled women” in the French public space—whatever the motive—is perceived by Frenchmen as a Muslim male challenge to their own control of French republican fraternal space.

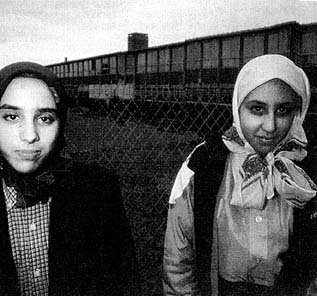

In this regard, the disruptions of masculinity brought about by deterritorialization are aptly captured, for the French side, by the particularly polysemic caricature shown in figure 46. The ugly, old, neutered Catholic nun is an obvious reference to the convergence of views of religious leaders of all denominations in favor of the veil. The nun stands for the old religious and patriarchal orders as seen from a modern French male point of view: denying access to women in the name of the old orders is out. The glamorization of the Muslim student is counterfactual, as a photograph of the students suggests (fig. 47). But it reveals what the unconscious stakes are: the unsupportable presence of forbidden women on the collective male territory of republican institutions. This is an old theme in the history of French/Maghrebi colonial relations, here given a new postcolonial twist.

Figure 46. “Give them this…they want this!” Le Canard enchainé, October 25, 1989.

Figure 47. Two students at the Collège Gabriel-Havez de Creil, Oise.

The presentation of both the nun and the sexy Muslim student as active agents is also counterfactual. While the caricatured nun is a classic example of scapegoating (the victim as oppressor), such presentation of the hypersexualized young Muslim woman as an autonomous actor is more complex. The cartoon is obviously addressed to the French viewer as paradigmatically male. It is also a deliberate attempt to enlist the sympathy of young Beurettes, quite congruent with the “chivalrous” position taken by most Frenchmen in the debate, who suddenly became champions of women’s rights. By fantasizing young Muslim women as autonomous actors (while denouncing their subjection!), it establishes with them an imagined alliance in the ridiculing of the old, repressive patriarchal orders represented by a nun (rather than an imam). Thus the French male viewer can fantasize complicity with a forbidden postcolonial object of desire. Finally, this fantastic seduction is staged without compromising a remarkably persistent misogyny, quite congruent with the more habitual exclusion of women from French republican fraternal space.