| • | • | • |

The Muslim World Day Parade

The oldest continuous civic parade in New York City is the Irish-American St. Patrick’s Day Parade, which celebrated its two hundredth and thirty-first year in 1993. Many of the subsequently established one hundred and sixty-eight annual ethnic day parades currently marching in downtown Manhattan borrow from the Irish prototype the established “grammar” of parade enactment: floats, marching bands, forward military-like march formation, related community groups, local politicians, banners, and so forth (Kelton 1985: 104). The recently inaugurated Muslim World Day Parade has added the performance of mosque architecture, Muslim procession, and prayer to the visual repertory of parade display.

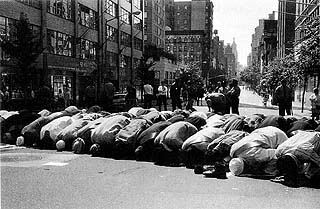

The Muslim World Day Parade begins with the marchers transforming the intersection of Lexington Avenue and Thirty-third Street into an outdoor mosque (fig. 37). The mosque is, literally, a masjid, “a place where one prostrates oneself [before God],” in the context of canonically fixed movements and verbal repetitions. Strips of plastic are laid down diagonally along Lexington Avenue so that participants and worshippers face the northeast corner of the two intersecting streets. The parade thus begins with an outdoor collective ceremony that demarcates the Muslim community and represents the primordial and recurrent moment of the sanctification of the community and the world by a prayerful gathering for which no specific architectural setting is necessary.

Figure 37. The 1991 Muslim World Day Parade: Lexington Avenue and Thirty-third Street becomes an outdoor mosque. Photograph by Susan Slyomovics.

Floats, a necessary feature of New York City parades, here take the form of scale models of the three holiest mosques of Islam, concrete expressions of the faith. Parade organizers present these mosques as cultural symbols to teach historic and religious values. First, the Ka‘ba, the holiest shrine in Islam, is identified as the “House of God, located in Makkah [Mecca], Saudi Arabia.” The second site, that of Muhammad’s heavenly ascent, is also identified by place: the Dome of the Rock, which “is” Jerusalem (al-Quds, the name of the mosque and the city). The third, the Masjid Al-Haram, is identified by its location in Medina and its role as the burial place of the Prophet. The information conveyed about these floats is presumably for non-Muslims.

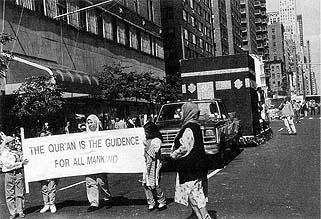

Indeed, a significant characteristic of the Muslim World Day Parade that contrasts with other parades is the visual importance and legibility of banners and signs. Parading banners or carrying the word of Islam becomes the parade’s most noteworthy feature and one that points, at the same time, to the omission of other classic parade entertainments: scantily clad females, women on display in floats, dancers, and so forth. Signage identifies specific Islamic organizations and sites unknown to the spectators, who thus acquire knowledge of New York’s newer religious groupings by reading the unfolding documentation of the breadth of Islam in the world or even of its local co-ethnic permutations (e.g., the Islamic Society of Staten Island, the Chinese Muslim organization, and PIEDAD, the acronym for the emerging Hispanic Muslim community).

Muslim marchers also carry their message by means of banners largely in English with quotes explaining Islam and specifically targeted to non-Muslims: “the qur’an is the guidence [sic] for all mankind” (fig. 38). Bystanders literally read ambulating sacred texts as if cinematic subtitles were translating the gestures of the marchers to the viewers. Signs proclaim, “There is no God but Allah the One, the Absolute, the Almighty, One Creator, One Humanity,” followed by signs bearing the names of Jewish and Christian prophets recognized by Islam, with Muhammad as the last seal of prophecy: “Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus and Mohammed.” Many signs emphasize Islam’s inclusive embrace of figures identified with Judeo-Christian religions, all of whom are honored by Islam. Such signs are also characteristics of the Muhurram procession in Canada and the Sufi processions in Britain described elsewhere in this volume (cf. Schubel, Werbner).

Figure 38. The 1991 Muslim World Day Parade: Banners preceding the float of the Ka‘ba. Photograph by Susan Slyomovics.

The domain in which the parade takes place is a prominent New York City public space: a march southward down Lexington Avenue heading from Thirty-third Street to Twenty-third Street, a route identified with South Asian food, travel, and sari stores. Thus, Muslim space on a New York City avenue can be temporarily created by combining two contrasting forms: the ephemeral structure and format of a civic parade and the monumentality of mosques on floats during the parade (Slyomovics 1995).