1. Making a Space for Everyday Ritual and Practice

1. Muslim Space and the Practice

of Architecture

A Personal Odyssey

Gulzar Haider

In 1960, courtesy of Fulbright-Hays, I was sent from Lahore to the University of Pittsburgh for six weeks to be “oriented” to American cultural, political, and educational systems. I was assigned to a host family, the Waynes, who were active in the YMCA and numerous other voluntary organizations. The Waynes took it upon themselves to help this stranger see some fascinating sides of America. Socially active Christians, they were also devout Americans. They took me to different church services, and I naturally asked if there were mosques in Pittsburgh. Mr. Wayne offered to take me to one, a building he confessed to not knowing too much about.

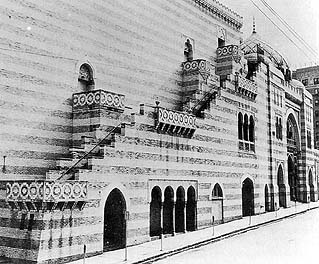

As we turned onto a minor street on the University of Pittsburgh campus, he pointed to a vertical neon sign that said in no uncertain terms “Syria Mosque.” Parking the car, we approached the building. I was fascinated, albeit with some premonition. I was riveted by the cursive Arabic calligraphy on the building: la ghalib il-Allah, “There is no victor but Allah,” the well-known refrain of Granada’s Alhambra (fig. 5). Horseshoe arches, horizontal bands of different colored bricks, decorative terra-cotta—all were devices to invoke a Moorish memory. Excitedly, I took a youthful step towards the lobby, when my host turned around and said, “This is not the kind of mosque in which you bend up and down facing Mecca. This is a meeting hall–theater built by Shriners, a nice bunch of people who build hospitals for crippled children and raise money through parades and circuses. They are the guys who dress up in satin baggies, embroidered vests, and fez caps.”[1]

Figure 5. The Shriners’ theater known as the “Syria Mosque,” Pittsburgh, Pa. Photograph by Gulzar Haider.

For a few seconds I felt as if the Waynes were playing a strange practical joke on me. And then I realized they were quite serious, composed, and a touch jubilant at their find. Two Americans and one Pakistani in search of a mosque had comically ended up in front of an architectural joke, a tasteless impersonation. A big poster in the lobby promised a live performance of Guys and Dolls later that month, proceeds to go to the Syria Mosque campaign for a children’s hospital.

We returned to a restaurant on the campus. From my seat, I could see the tall, spirelike building called the “Cathedral of Learning” through the glass, and a reflection of the “Syria Mosque” superimposed on it. With the passing years, I have realized that it was in that restaurant that the inherent ironies of the Muslim condition in the West, as expressed through architecture, got branded on my heart. Cathedral, a word from the sacred lexicon, had been appropriated by the university for its tallest and most celebrated building, aiming at the sky and daring it to open its gates and surrender its secrets. There were chapels for some denominations on the campus, but this “cathedral” was the seat of a new faith: the secular-humanistic pursuit of knowledge. And, by extension, the tall towers marking the heart of the American city were “cathedrals of Capitalism.”

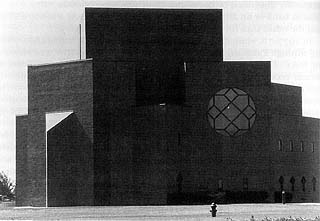

And there was the “Syria Mosque,” emblem of a pirated tradition used by the pirates to identify their “secret” brotherhood. Though charity, service, and volunteerism legitimized the Shriners, they could not erase their insensitive and callous misuse of another religion’s artistic vocabulary and symbolic grammar. This was the “oriental obsession” of the otherwise “puritanical” Europeans and Americans (Sweetman 1988). How was “Islamic architecture” represented in the West? Beyond the Shriners, there were movie theaters (fig. 6), casinos with names like “Gardens of Allah” and “Taj Mahal” (fig. 7), and—summing up the fantasies of the luxurious and exotic—the 1920s planned city of Opa-locka, Florida, whose vision sprang from a multimillionaire’s fascination with the film The Thief of Baghdad. In Opa-locka, everything had a dome and minaret (Luxner 1989).

Figure 6. Movie theater, Atlanta, Ga. Photograph by Gulzar Haider.

Figure 7. Trump casino: the Taj Mahal, Atlantic City, N.J. Photograph by Gulzar Haider.

I brought to my encounter with this American landscape an architectural ambivalence of my own, articulated as the draw of “modernity” against “tradition” in every sphere. My father had already made the choice to leave our ancestral home in the countryside, a choice redolent with symbolism, since that home had adjoined the shrine of a legendary saint whose descendants we were. My father chose to migrate to Lahore, a city of schools and colleges, of progress and promise for his sons, and the seat of the British governor of Punjab. There the “indigenous” was old and terminally ill, and the “alien” was modern and exemplary. We lived in Mughalpura but aspired to move to Modeltown. There were the Shalimar Gardens but we preferred to see the white-dressed white gents and ladies playing tennis in the Lawrence Gardens. There was Shah-‘Alam bazaar selling essence of sandalwood, but we felt special buying lime cordial from the Tolinton Market. Study of Urdu, Persian, and Arabic was a refuge of romantics or the last resort of the rejected; English was the essential requirement for those aspiring to serve the Raj. Kashmiri Bazaar led only to the then-decaying Wazir Khan Mosque. But the Mall, with its Government College, Mayo School of Arts, YMCA, Lloyds Bank, Imperial Bank, Regal Cinema, Charing Cross, Victoria Monument, and Aitcheson College was the road to the bright future. “Modern,” “European,” “British” and, later, “American”—in general, “foreign”—these words were the stuff that dreams were made of.

India got its freedom, and Pakistan came into being. Shakespeare Lane became Koocha-e-Saadi, one poet giving way to another, but the seeking heart did not change its bearings from Stratford to Shiraz. Thus, despite my heritage, I intellectually grew up, with much curiosity and some guilt, on the books and magazines of the British Council, United States Information Service, and Goethe Institute reading rooms. It was there that I met Christopher Wren and was mesmerized by the drawings in Banister Fletcher’s History of Architecture(1896). It was there that a book showed me for the first time the grand strokes of Sir Edwin Lutyens’s New Delhi. I was quite willing to trade Shah Jahan’s old “genie” for the new genie of the Raj.

Perhaps the most precious gift I received was the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright and, through him, the works of Louis Sullivan and the words of Walt Whitman. I can still recall the moment I “found” architecture. I had barely picked up a little book, Towards a New Architecture, by Le Corbusier (1927), when these words, “Eyes Which Do Not See,” leapt at me:

In the title “Eyes Which Do Not See” I sensed a resonance with the qur’anic parable of ignorance. And in the lines I sensed the clue to knowledge. Youth had found its manifesto! Already skeptical of “tradition,” now repelled by the casual use of “Islamic architecture” I encountered abroad, I wanted to be part of what was new. I resolved to resist dream makers like the pious South Asian Muslim in Miami who had retrieved a discarded pressure tank, placed it on a flat-roofed tract house as a “dome,” and topped off the whole thing with a crescent.A great epoch has begun.

There exists a new spirit.

There exists a mass of work conceived in the new spirit; it is to be met with particularly in industrial production.

Architecture is stifled by custom.

The “styles” are a lie.

Style is a unity of principle animating all the work of an epoch, the result of a state of mind which has its own special character.

Our own epoch is determining, day by day, its own style.

Our eyes, unhappily, are unable yet to discern it.

| • | • | • |

Wimbledon and the Isna Mosque in Plainfield: Interior Realities

When I reached the West, like the immigrants described in Regula Qureshi’s essay (this volume), I welcomed the company of fellow Muslims at prayer in makeshift settings. It was the practice that mattered in my case, as no doubt in many others, a practice promised to my mother when I left home. En route to America, on my very first Friday in the West, I prayed in a small English house on a corner lot in Wimbledon. There was no mihrab niche, just a depression in a side wall, a cold fireplace with a checkerboard border of green and brown ceramic tiles. A small chandelier with missing pieces of crystal was suspended asymmetrically in a corner. A rickety office chair with a gaudy plush rug draped over its back acted as the minbar pulpit. The prayer lines were oblique to the walls of the rooms and the congregation overflowed into the narrow hall and other nooks and corners. Was there anything mosquelike about this building, except that people had sincerely spread their mats in a common orientation, willingly performed their sajud in unison, and listened to someone’s sermon, accepting him as their imam?

Via the Syria Mosque, the Cathedral of Learning, and a few Fridays in transit I arrived at the old Georgian campus of the University of Illinois. About twenty of us prayed in the Faculty Club in the Illinois Union Building. We rearranged the furniture, spread rolls of green towel cloth at an estimated skewed angle, and listened to the sermon of a mathematician from Jordan, our “imam of the week.” I was awed by his audacity in presenting Divine Unity as a sphere and in talking of Asma’ al-Husna, Allah’s Beautiful Names (see also n. 5 below), as an ordered state of points defining that sphere. As I recall this, I wonder whether he was—as I would later become—a lost son seeking authentication, in this case through his grandfather’s philosophical geometry.

Soon I felt at home in a community of Muslim students. My turn to lead the prayers finally had to come. In my maiden sermon, I recited those verses of the Qur’an wherein God affirms Abraham and Ishmael’s building of the Ka‘ba as a House for Him.[2] Being away from the elders of my own culture, I felt safe in proposing my own exegesis: that the verse alluded to the sacred nature of architecture in support of the Divine commandments. And, by logical extension, I concluded that architecture could potentially be idolatrous when committed in defiance of the commandments. By 1963, a continental organization had been founded on our campus, the Muslim Student Association of USA and Canada. At its second annual convention, I again spoke, this time on nothing less than the architectural heritage of Muslims.

That year also, I was given permission to substitute for one of my studio projects the design of a mosque in North America. My understanding of Muslim architectural tradition was based on some memories of Lahore,[3] a childhood trip to Agra, and my recent visual encounters with six volumes of A. U. Pope and Phyllis Ackerman’s A Survey of Persian Art (1938–39). But tradition was definitely not a burning issue for a student “going abroad for studies in America.” Our dizzyingly optimistic, forward-looking American campus environment did not present the traditional versus the modern even as a legitimate question. Old was of interest only to historians. Old was the “problem.”

Thus the shift of orientation of the Masjid-e-Shah against the great maidan of Isfahan was posed as one of the problems that needed a new solution. I confronted the problem by eliminating it. My prayer hall was circular in plan: a symbol of “unity,” and free from the demands of orientation. I solved the problem of columns by using a single inverted dish-thin shell. I took the pool from the courtyard, made it much larger, and let my mosque float in it like a lotus. Finally, I proposed a bridge that was symbolically the path from the worldly—the profane parking lot—to the otherworldly, the prayer hall. Inventive energy has its own obsessive momentum, so I cut a laser slice of space right through the circular wall of the prayer hall to create a mihrab ending in the garden beyond. Perhaps the most daring gesture was to propose large-scale calligraphy on the top of the dome. The idea was to let the modern man in flight look down and recognize that this was a contemporary mosque in the West.

The project was graded excellent, and I was sincerely proud of my achievement. Three decades later, I am grateful to God that there was no government, nor any other patron around me, to help me commit this crime on a real site. There are grand projects of that decade across the Muslim world, designed when young architects who had studied in Sydney or London or New York returned to build their modernity-driven, metamorphosed mosques. These are places that distort the imagination of the one who prays. Modernity, in the design context, was too self-consumptive, self-driven, ever-changing, to be relevant to the timeless protocol of the human body on a humble prayer mat engaged in qiyam (standing), ruku‘ (bowing), sajud (prostration).…May God be Merciful to the one who recognizes his mistakes.

My next mosque design was in 1968–69, after I had earned my bachelor’sdegree in architecture from Illinois. This was a joint project with Mukhtar Khalil, another Muslim student. We entered the competition for the Grand National Mosque in Islamabad (now the well-known Faisal Mosque). The site and the beautiful surroundings, complex program, and grandiose scale encouraged us to provide an equally heroic design response. We conceived an Islamic “St. Mark’s”: a trapezoidal setting, with educational blocks on three sides, a horizontal plaza with geometric stone patterns, and an artificially twisted entrance to create an element of surprise. The mihrab area was a round sculpted form inspired by Ronchamp. And further to avoid any remote chance that someone might mistake our building for a “traditional” structure, we proposed a minaret tower four hundred feet high and fifty feet in diameter, visible from the peaks of the Murree Hills, covered with turquoise-glazed tiles, containing a library and a museum on the model of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. St. Mark’s, Ronchamp, the Guggenheim, and a heavy dose of abstract calligraphy, all in one project! The sirens of modernity had cast their spell. It was my good fortune that the design got eaten by termites in a Post Office warehouse.

For about ten years I struggled with various Muslim communities in search of an opportunity to design a place of prayer. It was a period of trials and professional wanderings (Haider 1990). Nothing is more telling of the communal fragmentation of ideas and images than the kinds of mosques people carry in their minds. Recalling my encounters, I have sometimes felt like a volunteer nurse in a room full of Alzheimer’s patients at various stages of their condition. My own mind being a page with far too many images stamped on it, I have always empathized with community luminaries heatedly debating what their mosque should look like—not infrequently illustrated by pages torn from a mosque calendar offered by a Muslim bank or an airline. Usually the majority side favors a modern style and the other aims for recognizable “conventional” imagery.

In 1977–78, while spending a sabbatical year in Saudi Arabia and traveling through Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey, I saw the destructive and alienating force of architecture in the name of progress. I started to experience a certain ecology of architecture, literature, belief, philosophy, commerce, culture, and craft still operating in the old bazaars behind the modern façades of the cities I visited. I began seeing architecture as a formative element in culture rather than a mute expression of it—an isolated bit of gallery artwork to be reviewed, honored, bought, sold, and collected.

In 1979, I was invited to design a national headquarters mosque in Plainfield, Indiana for the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA), which had evolved from the Muslim Student Association founded sixteen years earlier. It was the same MSA that had started at my university in Urbana, and the person who invited me was Mukhtar Khalil, my co-contestant in the Islamabad mosque competition of 1968. The invitation was an honor I received with many self-doubts. I recalled Abraham’s House for God, and started my search for a place of prayer for those who, at home or in “occidental exile,”[4] turn their faces to that Blessed House in Mecca and recite:

I was also very intrigued by the Divine attributes expressed in two of the names of God, “The Hidden” and “The Manifest.” I wanted to find in them a special wisdom for the designer, who must create but not confront, offer but not attack, and yet withal express the profound in a language understandable and pleasing to the listener.[5]

Lo I have turned my face Firmly and truly Toward Him who willed The heavens and the earth And never shall I assign Partners to Him. (Qur’an 6:79)

To distinguish the exterior from interior, I chose to veil this mosque, evoking the need for meaningful and purposeful dissimulation. I thought of my building as an oyster whose brilliance and essence were internal, while the expressed form sought human ecological harmony, modesty, even anonymity. This was the period, after all, when I had gotten used to friends Americanizing my name to “Golz” and my wife’s from Santosh to “Sandy.”

In my design, I resisted Western exploitation of the visual symbols of Islamic “tradition” rather than the tradition itself. During the nineteenth century and the prewar twentieth, Muslim reality had been observed and projected through many distorting prisms. There were paintings, romantic fictions, exotic travelogues, and, later, circuses, movies, movie theaters, magic potions, exotic foods, and music—all capitalizing on immediate expectations of magic fortunes and paradisiacal sensuality. From Las Vegas and Atlantic City “pleasures for sale” to Barnum and Bailey’s “Greatest Show on Earth” to Shriners’ temples, all had exploited, with gluttonous appetite, the symbols associated with the Muslim past (Said 1978).

The project was built and has been used since 1982 (fig. 8). It has no expressed dome, although inside there are three domes creating an unmistakable space of Islamic prayer. Those who have been inside are struck by the “mosqueness” of it all. It remains an enigma, however, especially to those Muslims who are used to seeing mosques and not praying in them. Like the makeshift mosque in Wimbledon, what mattered in the Plainfield mosque was the practice—in this case intended to be fostered by the design—within.

Figure 8. The Islamic Society of North America headquarters mosque, Plainfield, Ind. Photograph by Gulzar Haider.

| • | • | • |

The Bai‘tul Islam Mosque, Toronto, and Back to Wimbledon: Externalizing Islam

The demand for what is seen as visual authenticity in the mosque, however, has intensified over the past decade. On the one hand, this is a natural sign of the maturation of the first wave of postwar immigrants, many of whom came for education and then settled for better economic and professional opportunities. On the other hand, this is also a sign that efforts at “melting into the pot” have given way to assertion of a Muslim identity as a better alternative. There are also global movements afoot that have given Muslims in the diaspora a sense of identity and linkage as part of the umma, or worldwide Muslim community. Some have now started to express “dome and minaret envy,” in relation, for example, to the Plainfield mosque.

These years have also been a period of intense energy in architectural-academic discourse as modernism started to come under questioning and later open attack. The word postmodernism came to evoke everything from zealous commitment to ridicule. New terms such as postfunctionalism,poststructuralism,deconstructivism,logocentricism, and even reconstructivism made their appearance.

Even so, the postfunctionalist search for “meaning” and the return of “philosophical inquiry” through architecture has been timely for the emergent discourse on sacred architecture. For Muslims, there has been much discussion about the value of the Islamic heritage within a technologically homogenizing world. The symposia of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, in particular, have brought the protagonists of tradition and those of modernity around the same table under the mostly civilizing gaze of some philosophers and itinerant sages. These symposia have taught me to treat my most cherished architectural conceptions with a humbling doubt.

For me, the academic inquisition against modernism has provided numerous opportunities. As the design canons of modernist minimality and pure composition have come under attack, there has been a new air of respectability for the study of ornament, craft, tradition, form, symbol, text, inscriptions, and, above all, the philosophical underpinnings of architectural intentions. There is now legitimacy for seeking to know culture though the direct experience of art—“tactile knowing,” as we ended up calling it. It was the interpretive drawing of carpets, miniatures, and gardens, as well as the recitation of poetry, that opened up Islamic culture for many of my Canadian students.

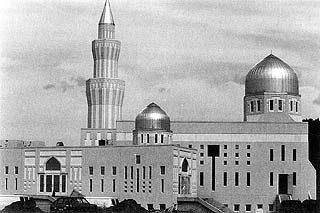

In 1987, almost ten years after the ISNA mosque, I received a commission to design a large mosque in Toronto. By then, numerous North American Muslim communities had shown a desire for assertion through architecture, rather than anonymity through dissimulation. This desire was particularly keen in this case: the mosque was to be the national headquarters of the Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam, a community declared out of Islamic bounds by act of the Government of Pakistan in 1974, which now, quite simply, wanted all the architectural help it could get to express its Islamic presence in Canada (Haider 1990). I was advised to reject this commission, lest I risk my future and never get another job, or even risk my hereafter by “partnership in the crime of Ahmadiyyat.” I am not an Ahmadi Muslim, and I am not qualified to make pronouncements on Islam or meter others’ Islamicity. I am convinced, however, that I have designed a mosque, and that what are performed there are prayers in the finest tradition of Islam.

In designing the Toronto mosque, I used the prayer rug as a conceptual inspiration, as well as a source of formal and decorative discipline. Conceptually, the prayer rug, as it is spread out and qibla-directed, defines the elemental place of prayer. As the believer positions and orients his or her body on it and goes through various stages of salat, the Islamic ritual prayer, a place-space is defined, in the physical and temporal as well as experiential sense, that has all the essential attributes of a mosque. As the prayerful body interacts with the qibla-directed Cartesian planes established by the prayer rug, so the collectivity, the parallel rows of the community of believers, resonates with the architectural space of the mosque. All design decisions, especially the proportions of the space, the pattern and the placement of fenestration, the sequential placement of entrance and arrival, tile patterns and carpet layout are aimed at achieving this resonance. The prayer rug rises out of its horizontal plane and wraps itself around the space.

This mosque started with the study of prayer rugs; and its final act of design resulted in a prayer rug that has been sand-etched in the glass of the doors marking the entrance to the prayer hall. If the Plainfield mosque might seem like a corporate headquarters to the freeway observer driving by, the Toronto mosque boldly asserts an Islamic profile, reclaiming the conventional minaret and dome for their appropriate ends (fig. 9).

Figure 9. The Bai‘tul Islam mosque, Toronto. Photograph by Gulzar Haider.

Twenty-five years after the first encounter, I had a chance to visit Wimbledon again. The house-mosque was now wrapped with a glazed finish; arched windows sat squeezed into what were at one time rectangular openings; the parapet had what seemed like an endless line of sharp crescents; and there were a number of token minaret domes, whose profile came less from any architectural tradition than from the illustrations of the “Arabian Nights.” By now, they, too, had felt compelled to “Islamize” that sometime English house.

My innocent but bizarre encounter with the “Syria Mosque” has never left me. Like a plow in the field, it turns inside out what would otherwise have been quiet, sedate, but decaying chambers of my mind. I have never ceased raising questions about what a North American mosque might be and become. The mosque will have to attain its rightful and self-assured place in world society, so that later generations who choose to come to North America will not be faced by a theater garbed in Moorish dress.

Muslims living in the non-Islamic West face an unparalleled opportunity. Theirs is a promising exile: a freedom of thought, action, and inquiry unknown in the contemporary Muslim world. They are challenged by a milieu that takes pride in oppositional provocations. Those who can break free of the inertial ties of national and ethnic personas will be the ones who will forge an Islamicity hitherto unexperienced. They have the freedom to question the canons of traditional expression. Their very exile, understood as separation from the center, will make the expressions of Islam more profound, whether in literature, music, art, or architecture.

Muslim minorities in the non-Muslim world will ultimately realize that their history has put them in a position somehow reminiscent of the Prophet’s Meccan period. Their isolation will purify and strengthen their belief. It will refine their thought and make their tools precise, and at an appropriate time, they will start to send “expressive” postcards home. Then there will begin another migration, not in space and time, but from blindness of a certain kind to a clearer vision, from spiritless materiality toward expressive spirituality.

Notes

Editor’s note: I prepared this essay from a draft paper by Gulzar Haider, “Prayer Rugs Lost and Found: In Search of Mosque Architecture” (1993), a slide presentation at the SSRC (May 13, 1989), and the published essays cited. I have organized and edited the material, provided linkage where necessary, and chosen the illustrations.—BDM

1. The Shriners are formally known as the Ancient Arabic Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, “an auxiliary of the Masonic order…dedicated to good fellowship, health programs, charitable works, etc.” (Random House Dictionary, 2d ed., s.v. “Shriner”).

2. “Call to mind also when Abraham and Ishmael raised the foundations of the ‘House’ and (having done so) prayed: O Lord, accept this offering from us, it is Thou Who are All-Hearing, All-Knowing” (Qu’ran, 2:128).

3. Lahore is well known for such masterpieces of Islamic architecture as the Badshahi Mosque, Jahangir’s Tomb, and Shalimar Gardens.

4. The phrase is borrowed with respect and apology from the great Muslim sage Shihab al-Din Yahya al-Suhrawardi, who spoke of al-ghurbat al-gharbiyya (translated by H. Corbin and S. H. Nasr as “occidental exile”) as the state of the soul separated from its divine origin. See Nasr 1964: 64–68.

5. Al-Batin (Hidden), al-Zahir (Manifest), two of the “Ninety-nine” Asma’ al Husna (Beautiful Names of God). Of much philosophical interest through Muslim history, the “Names” are sometimes proposed to be irreducible facets of the Divine Being that may reflect the seeker’s self to himself and thus make possible gnosis, the cognizance of the destiny of the seeker’s soul. The two names al-Batin and al-Zahir are of special interest to architects in pursuit of the silent eloquence of space and the quintessential presence of form. For an initiation into the relationship between esoteric philosophy of Islam and its architectural expression, I am indebted to Ardalan and Bakhtiar 1973.

Works Cited

Ardalan, Nader, and Laleh Bakhtiar. 1973. The Sense of Unity: The Sufi Tradition in Persian Architecture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fletcher, Banister. 1896. A History of Architecture for the. Student, Craftsman, and Amateur: Being a Comparative View from the Earliest Period. 2d ed. London: B. T. Batsford.

Haider, Gulzar. 1990. “‘Brother in Islam, Please Draw Us a Mosque.’ Muslims in the West: A Personal Account.” In Expressions of Islam in Buildings, pp. 155–66. Proceedings of an International Seminar sponsored by the Aga Khan Award for Architecture and the Indonesian Institute of Architecture, Jakarta, October 15–19, 1990. Aga Khan Award for Architecture, Geneva.

——————. 1992. “The Bai‘tul-Islam Mosque: Architectural Intentions.” In Ahmadi Muslims: A Brief Introduction, pp. 10–12. Ontario: Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam.

Le Corbusier. 1927. Towards a New Architecture. Translated by Frederick Etchells. New York: Brewer & Warren.

Luxner, Larry. 1989. “Opa-locka Rising.” Aramco World Magazine, September– October 1989, pp. 2–7.

Nasr, S. H. 1964. Three Muslim Sages: Avicenna, Suhrawardi, Ibn ‘Arabi. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Pope, Arthur Urban, and Phyllis Ackerman, eds. 1938–39. A Survey of Persian Art. London: Oxford University Press.

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

Sweetman, John E. 1988. The Oriental Obsession: Islamic. Inspiration in British and American Art and Architecture, 1500–1920. New York: Cambridge University Press.

2. Transcending Space

Recitation and Community among South Asian

Muslims in Canada

Regula Burckhardt Qureshi

Islamic practice is central in creating meaning and community among many first-generation Muslim families in Canada. Characteristic of that practice are the four recitational assemblies described below, all focused on shared articulation of religious and cherished words: milad, hymns and homilies in praise of the Prophet; zikr, Sufi invocational phrases and hymns; qur’ankhwani, one or more complete recitations of the Qur’an; and ayat-e-karima, 125,000 reiterations of a qur’anic verse.[1] South Asian Muslims have become well established across the urban landscape of Canada, and they have created a strong community life on the foundation of shared events internal to the community.

Advantaged by their access to English and English institutions, as well as by their successful entry into higher education, professions, and services, South Asians stand out among immigrants from the Muslim world. Originating mainly in Pakistan, but also in India, Bangladesh, East Africa, and Sri Lanka, they are linked by a common language, Urdu, and by a cosmopolitan culture shared by urban Muslims all over the Indian subcontinent. Immigration to Canada has largely come from upper- and middle-class families, who have also set the tone of community life in the new country; only recently, liberalized Canadian sponsorship laws have enabled immigration from socially and educationally less privileged backgrounds. These later immigrants benefit from the growing community network and the Canadian government’s multicultural outreach. As a result, with their social, educational, and health needs met by a comprehensive governmental support system, South Asian Muslims in Canada are overall reasonably prosperous and upwardly mobile, owning and replacing cars and homes, directing their children into preferred professional training, and sponsoring the immigration of relatives from the home country.

South Asian Muslims have, in the course of time, built mosques and become involved in the public representation of Islam through its buildings and organizations. In Edmonton, for example, to celebrate the ‘Id holidays (and, for a few, to attend weekly prayers), they initially joined the Arab-Canadian congregation in the small al-Rashid Mosque,[2] contributed to its impressive new building, and eventually built the Markaz ul Islam as a mosque for the Pakistani community. But to focus on this public face leaves the observer on the outside and on the surface; it misses a strong community life that is deeply meaningful and quite private. This privacy is far from exclusive, since South Asian Muslims hold sharing and hospitality as primary values. People love to open their homes to share special life events and religious practices integral to their warmly social community life.[3]

Islam has been a major determinant of individual and group identity among these immigrants in Canada, mediated by their shared language and regional lifestyle. More important, it offers its ideational foundation and a rich set of practices to give salient articulation to the uncharted exigencies of life in Canada. This process of “making Muslim space” for the Muslim diaspora within the larger Western context must take as its starting point one that is community-internal, one that defines, not what outsiders see, but what insiders identify as creating “space” for Islam.

In his comprehensive search for visually perceptible symbols and signs in Islam, Oleg Grabar cautiously but inevitably concludes that “Islamic culture finds its means of self-representation in hearing and acting rather than in seeing,” for “it is not forms which identify Islamic culture…but sounds, history, and a mode of life” (1983: 31, 29). Remarkable for coming from a specialist in the visual domain (Islamic architecture), this insight completely affirms my own experience as a specialist in sound; more important, it resounds from a chorus of Muslim voices speaking in both poetry and prose. Starting with the Prophet of Islam himself, these voices say in essence that Muslim space is where Muslims prevail (Abel 1965: 127). From the hadis of the Prophet Muhammad, which universalize the mosque as any place where Muslims pray,[4] to Sufi literature, where a tavern can become a cell (al-Hujwiri: 409), the theme of “multiplicity of purpose and flexibility of space” is a persuasive one in Islamic discourse. It also marks the history of Islamic “built space” itself (Jones 1978: 162).

Spatial cannot, therefore, be reduced to meaning visual and accessible to reification, as in a good deal of Western scholarship (Durkheim 1938; Moravia 1976). The new ethnography based on dialogue and process considers itself more appropriately represented by the modalities of the aural and oral (Fabian 1983; Ong 1970), which provide a better starting point for a dialectical communication giving access to the voices of those who are being studied.

Running counter to the widespread Western view of an Islam located in minarets, calligraphy, and carpets, what Muslims have taught me to associate with their religion are its commitment to universality, its resources of portability, its focus on a single sacred center, and its singularly verbal message. Islamic praxis transcends local space primarily by aural, not visual, communication. Consider the following vivid images of Canadian Muslim living: ritual prayers recited using towels as makeshift prayer rugs on any available floor area, subject only to identifying the direction of the Ka‘ba; of reading the Qur’an during spare moments at the office desk; of holding a Sufi zikr seated informally across the space facing an unlit fireplace; of a funeral oration in the gymnasium that is part of the mosque complex; of breaking the fast during Ramadan in front of a TV or anywhere in the house; of a list of qur’anic invocations held by a magnet on the refrigerator door. What expresses Muslim identity—or experience, or faith—is process, at the core of which are words: the words of the qur’anic Message, words that explain and interpret the Message, words that praise God and his Messenger, words that express the believer’s submission—“Islam.” This emphasis resonates throughout the essays in this volume.

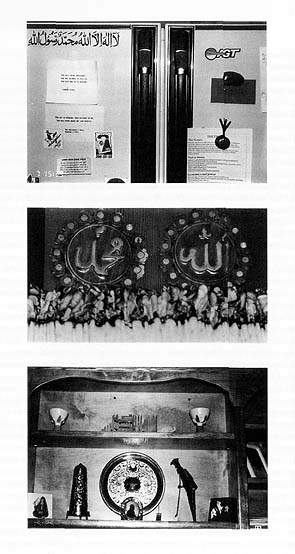

Key to proper utterance is the believer’s intent. This is most clearly articulated in the classical Sufi writings on the assemblies for the performance of zikr and sama’ (listening to mystical poetry). These texts postulate neutral space and time,[5] for what creates the actual ritual are its words, appropriately uttered and received. Muslims are linked by words, above all the divine Message of God in the Qur’an, and by the Ka‘ba, toward which they all face during ritual prayer (salat). Such words are rendered visual and even decorative, but the purpose is to remind the Muslim to utter these words by reading or reciting them. Thus in a mosque all the outstanding spatial features are directly linked to both the Word and its actualization: from the minaret for reciting adhan and qur’anic calligraphy on the outside to the mihrab niche for the imam to lead the prayer and the mimbar from which he speaks the khutba (sermon). In the home, the Qur’an is always present; it is not displayed but placed in an elevated location as a mark of respect. What needs to be stressed is that for Muslims neither the Qur’an nor any visual Islamic display is a locus of contemplation; they are meant to initiate articulation and action.

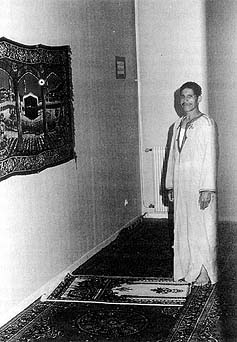

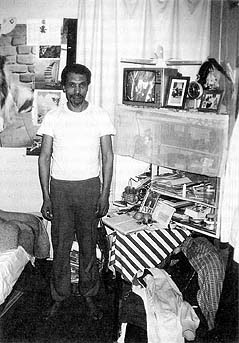

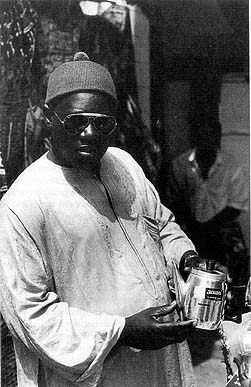

Figures 10a-b. The verbal-visual presence of Islam in a Canadian home. Photographs by Regula Burckhardt Qureshi.

As for the visual articulation of Muslim identity in today’s South Asian Muslim home in Canada, what dominates is the qur’anic word (fig. 10). Artistically calligraphed qur’anic verses are displayed in many forms: prints in a Western-style rectangular picture frame, ornamental trays or plates of etched or embossed brass or copper, religious words on art objects collected from different parts of the Islamic world, including the South Asian homeland. Pakistan, especially, offers items that are both traditional, such as enamelled ceramic plates or tiles, and modern, such as calligraphic sculptures made of recently discovered marble. What all these calligraphic items have in common, regardless of differences in material, style, or connotation, is their primary function: to convey a religious verbal message. The messages may be the names of God or the names of the Prophet, or the kalma, “La llaha-il Allah, Muhammad al-Rasul Allah” (“There is no god but God, and Muhammad is his Prophet”). They are often a part of the Qur’an, for example, the sura al-Rahman (sura 55), on divine beneficence, and include the words that open the Qur’an and preface each sura: “In the Name of God most Gracious, most Merciful” (“Bismillah al-rahman al-rahim”); they are recited when a Muslim begins any task, from beginning a meal to starting on a journey. Also favored are the four qul,[6] especially the sura al-Ikhlas (“Qul hu wallahu ahad…”);[7] these are short suras beneficial for any place and occasion. A special passage selected to give safety to home and family is the “Ayat al-Kursi.”[8] Complementing these verbal messages are occasional pictorial representations of the Ka‘ba, which can take the place of a painting to adorn the living room.[9]

Aesthetically less relevant, but all the more clearly action-oriented in function are words that convey information to facilitate religious observances, mainly in the form of an Islamic calendar that marks the lunar months and days, religious holidays, and times for starting and ending the fast during the month of Ramadan and perhaps for the five daily prayers. In addition, families with children may display words for Muslim living, for their children to absorb, perhaps qur’anic verses on a calendar supplied by the local mosque or simply a list of religiously appropriate responses to different life situations in Arabic—for instance, “Masha’allah” (“by the grace of God”) or “Insha’allah” (“God willing”). Individual homes, of course, differ widely in the kind, extent, and style of visual-spatial expression of Islamic words.

Engaging in the articulation of Islamic word and performing the relevant actions form the basis of individual Muslim identity; sharing that engagement links Muslims into a community. The primary ritual of a Muslim is salat, the prescribed ritual prayer offered five times each day, for which South Asian usage employs the Persian term namaz. Even though a Western observer’s visual attention may be directed to the ritual gestures of prostration, it needs to be stressed that the primary action of namaz is verbal: one “says” or “recites” the prayer (in Urdu: namaz parhna).[10] Another form of individual recitation is qir’at, the reading of chosen passages from the Qur’an, either following namaz or at any other suitable time. Normally silent, such recitation or reading may also be chanted; this sets apart the sound of the words by making them beautiful (khushilhan), while the act of recitation is set apart by a respectful and modest posture and physical attitude. Most important, religious recitation means actually saying the words, even when reading silently, not just visually perusing them, as in the Western sense of reading. Indeed, the fact that Urdu speakers apply the term reading to both silent reading and voiced recitation or chant denotes less a limitation in vocabulary than a fundamentally different conception of the act of reading itself (Tomlinson 1993).

In addition to namaz, reading or reciting religious words is also carried out as a structural, collective activity in the four kinds of assemblies described here. They fall into two different formats. Milad and zikr follow a traditional performative format of South Asia in which one or several persons recite to the assembled audience. Led by reciters, they require competence and result in a structured performance sequence. The Shi‘a majlis (Schubel, this volume) follows the same pattern (Qureshi 1981). Qur’ankhwani and ayat-e-karima, on the other hand, are participatory gatherings of silent recitation, which is shared by all. All four assemblies share basic features of setting and overall procedure.

First of all, the prime locus for holding these assemblies remains the home, community associations and public buildings notwithstanding, for the processes of community formation emanate essentially from individual families, as do the rituals or religious “performance events” that link people of the same group. The distinct subcultures of men and women contribute to and are shaped by these occasions. Visually apparent in separate seating arrangements and formal social space generally, what this “segregation” means—rather than what it displays—is interaction and mutual reinforcement among members of the same gender within and across families. Supported by their single-gender network, both men and women mobilize support for initiatives such as the holding of religious assemblies appropriate to their family’s personal circumstances.

Over the years in Canada, spatially separated socializing has visibly increased. On the surface, this trend would seem to run counter to increasing adaptation to the Western host society. In fact, it represents an “internal adaptation” to more extensive familylike socializing among people not related by family ties. Given this reality, spatial separation is a response, for example, to the concerns of elderly parents, especially grandmothers, who are unaccustomed to mixed socializing. It also reflects concern for creating an appropriate social environment for growing daughters by reinforcing the traditional pattern of restricted interaction between the sexes (Qureshi 1991). This trend has been further reinforced by the conservative impact of transnational Islamic movements.

In reality, however, networks of connectedness among women and among men have always been strong. This point bears emphasizing, precisely because the spatial element of female seclusion tends to claim much attention at the expense of recognizing the autonomous role of women in South Asian Muslim homes. Home-based affairs are always in the hands of women, who also, of course, produce the repasts provided for social or religious “functions” outside the home.

The key change in religious assemblies from the pattern of the homeland is that they now take place largely in this context of domestic hospitality and socializing (Qureshi 1972; 1980: v; 1981). The separation of men and women is facilitated by modern house plans that include both a drawing room and a family room, with men typically in the formal drawing room, leaving women to the family room or other less formal parts of the house. A similar use of space has been described for the typically modest homes of South Asian Muslims in Britain (Shaw 1988) and for African-American Muslims (McCloud, this volume).

| • | • | • |

Milad

Milad is the devotional assembly in the most traditional sense, celebrating the Prophet’s birth on the twelfth day of the month Rabi ul-Awwal. Practiced by Muslims all over South Asia, the milad has an established format. A small reciting group presents a sequence of chanted[11] hymns in praise of the Prophet (na‘t), alternating with spoken homilies (riwayat,bayan) and interspersed with Arabic praise litanies (durud). Like all religious events, a milad begins with God, often in the form of a hymn of praise to God (hamd); sometimes it is preceded by qur’anic recitation. A salutational hymn to the Prophet (salam) followed by an intercessory prayer to God (du‘a) and a recitation of al-Fatiha (sura 1), the sura dedicated to prayer for the dead, conclude the event (fig. 11).

Figure 11. Hymns recited at Milad-e-Akbar: Durud (litany in praise of the Prophet); Na‘t (“Allah Allah Allahu”); Salam (“Ya Nabi Salam Alaika”); and Du‘a.

Milads are held during the entire month of Rabi ul-Awwal and also on auspicious occasions such as a move into a new house, professional success, and family events such as the arrival of a daughter-in-law from Pakistan or the birth of a healthy grandchild. Milads are predominantly a women’s tradition, and even in South Asia, they take place mainly in homes, with women reciting.[12] In Canada, the smaller Muslim community of the 1960s and 1970s saw milads that included both women and men and their then mostly small children.

One of many such events from the late 1970s stands out in my memory, a milad held in conjunction with a bismillah celebration, a ceremony that initiates a child’s education, traditionally at the age of four years and four months. The milad was organized to precede the brief ceremony as an expression of praise and thanks, and to invoke blessings. The ceremony itself bespeaks the centrality of reading and reciting the qur’anic word: a religious teacher or family elder guides the child’s hand to write the first letters of the Arabic Urdu alphabet and recites with her the opening words of the Qur’an: “Bismillah al-rahman al-rahim” (“In the name of God, the all-compassionate, the all-merciful”).

As friends gradually arrived, they were invited to settle down in the living- and dining-room area, which was cleared of furniture and covered with white sheets, back support being offered by pillows and bolsters, as well as by the walls. A special carpet was placed against one wall for the reciters. An attractive cloth packet containing the book Milad-e-Akbar (Akbar Warsi n.d.), a compilation of hymns and prose sermons from which recitations would be chosen, was placed on a decorative raised pillow. The guests sat down along the other walls, eventually forming a loose circle around the entire area. Men and women naturally chose to sit in different areas of the s-shaped space, joining friends among their gender group and talking informally. The hostess had previously asked a friend who was a competent reciter for the recitation, and the latter then asked two other invited friends to join her. The milad was relatively short, with only two sets of hymns and riwayat, followed by the salam and then the du‘a.

Then the bismillah ceremony followed, all conducted by the women, with the men participating as listeners. Everyone’s attention was on the beautifully dressed little girl and her words of recitation. The joyous event concluded with a sumptuous dinner.

Today, preference has shifted to all-female milads, supported by the trend noted above toward separating social space by gender. Excluding men also allows the hostess to include participants from twice as many households, which is socially desirable given the expanding personal circles brought about by the larger numbers of immigrants. These events are now multigenerational. Overall, the recitation may lack the performative creativity of the seasoned semiprofessionals of the Indian subcontinent. But, as in a recent “housewarming” milad where the grandmother of the young hostess presided over four generations (fig. 12), milads often do achieve an intensely religious mood in a setting of relaxed intimacy.

Figure 12. Recitation of the great-grandmother. Photograph by Yasmeen Nizam.

| • | • | • |

Zikr

Zikr (“recollection”) is the Sufi practice of remembering God by repeating His name. The most commonly recited zikr phrases are linked to the articulation of the kalma: “Allahu” (God is); “La ilaha il-Allah” (There is no God but God); and “il-Allah” (The only God). Their constant repetition is intended to create a spiritual-emotional experience of nearness to God. The zikr assembly is convened by a spiritual leader, who is responsible for intoning and coordinating the repeated reiteration of these powerful invocations, as well as for providing spiritual guidance for the experience.

Zikr assemblies are relatively uncommon in Canada because of the scarcity of Sufis among South Asian Muslim immigrants, and among middle- and upper-class Muslims in South Asia generally. Many Muslims do not really approve of the practice. At a zikr gathering held in the 1980s, non-Sufis were invited as personal friends, or as an outreach gesture on behalf of Sufism and of the host’s Sufi lineage. After a fine dinner, the guests were seated in the family room, oriented around the host, who informally introduced the significance and purpose of the zikr. He then initiated the zikr recitation with the universal opening phrase of the kalma, speaking the words rhythmically and accompanying them with the traditional gesture of bowing the head and placing the right hand on the heart, whose pulse is understood as the Sufi’s inner zikr. The participants joined in with either voiced or silent zikr (zikr-e-jali or zikr-e-khafi).

Here the performer-audience opposition is less total than in the milad because of active audience participation. Ideally, a Sufi assembly would also offer the listeners the spiritually involving experience of sama’, listening to mystical hymns (qawwali), but that is rarely possible because of the lack of trained performers. For this reason, the few Sufis who have held such assemblies in Canada reach for the resource of zikr, which requires only a modicum of recitational skill. Another recent trend is the playing of qawwali recordings to evoke the experience of sama’.

| • | • | • |

Qur’ankhwani

Qur’ankhwani and ayat-e-karima are distinctly nonperformative and therefore differ from the other two assemblies fundamentally in their organizational structure. In these participatory assemblies, people gather to share in the task of completing a major task of recitation: the complete text of the Qur’an in qur’ankhwani, and 125,000 utterances of a specified qur’anic verse in ayat-e-karima.[13] Each individual recites soundlessly, so that neither spatial nor temporal management is required, although there is informal coordination between reciters. Women and men gather in separate rooms with sheet-covered floors, seated along walls or furniture for back support, their heads covered “as a mark of respect.” Participants focus on the task of reciting, their lips often moving silently as they speak each word to themselves.

Qur’ankhwani entails the recitation of the whole Qur’an.[14] This is done traditionally during Ramadan and on the occasion of a death, as well as on the soyem and chehlum (commemorations on the third and fortieth days after death), and the anniversary of a death (barsi). In recent years, qur’ankhwani has also been organized on auspicious occasions, and more generally to invoke a blessing (for instance, on a new home). The aim is to complete the reading of at least one and preferably several Qur’ans, for these represent accumulated blessings dedicated to the person or cause for whom the qur’ankhwani is being held.

One senior widow holds a qur’ankhwani, followed by a meal, each year on the weekend following the death anniversary of her husband, who died ten years ago. In order not to fall short of at least one complete reading of the Qur’an, her two sons and daughters-in-law begin to read one or two hours before the event starts, and if many people arrive early, a second or even a third Qur’an might be completed. If the reading still falls short of the goal, the recitation is completed later by members of the household.

The host has made the Qur’an available in the form of thirty separately bound sections, the siparas, which form the traditional units of qur’ankhwani recitation and are familiar to everyone. On this occasion, a friend brought a second set, so that instead of sharing, the men’s room and the women’s room each had its own. Each guest picked up one siparah, perhaps selecting a particular siparah containing a favored sura. Completed siparahs were placed separately to avoid duplication. Someone already present quietly provided newcomers with directions as needed. Anyone not ba-wuzu (ritually clean)[15] did not recite but sat quietly. Those who read quickly soon added their siparas to the pile of completed ones, and each picked up another. When none were left in the women’s room, unread siparas were brought in from the men’s room, since they, being fewer in number, had not been able to read as much. Each person who had completed his or her last sipara sat quietly or, in the case of women, went to the kitchen to help and socialize. On completion of the Qur’an, the host’s daughter placed a tray with a dish of halva on the sheet-covered floor of the living room where the women had been sitting, and everyone recited the sura al-Fatiha, followed by the du‘a to bring peace to the dead person and to bless the food that was later placed on the table along with the halva.

Now everyone rose, removed their head coverings, and proceeded to enjoy the company of friends and a delicious meal. Participants in a qur’ankhwani work hard for the host to gain religious merit or blessings; this generates a special sense of reciprocity between host and guest, arising from a genuine sense of religious commitment.

| • | • | • |

Ayat-E-Karima

Ayat-e-karima denotes the famous qur’anic verse in which the Prophet Jonah, in the belly of the whale, cries out to God admitting his wrong, and God then saves him, saying, “and thus do we deliver those who have faith” (21:88).[16] The words of the ayat thus recall and invoke God’s mercy, hence the name karima (“merciful”): “La Ilaha Illah anta subhaneka inni kunto min az-zalemin” (There is no god but Thou; glory to Thee; I was indeed wrong.) When God’s help is needed for something important, this verse is chosen to be recited a total of 125,000 times. The task is undertaken collectively in this least structured of all assemblies, for the recitation consists of a single phrase known to all, so that there is no need for either leadership or printed text.

In 1986, a Pakistani-Canadian invited her friends to an ayat-e-karima when her husband was recovering from a serious illness. Given the immensity of the task, a late morning time on a Sunday was chosen, and many friends were invited. A large number came to support this effort; most brought along their tasbihs (rosaries) of one hundred beads to facilitate counting, or they picked up one of the tasbihs provided by the host. To add up individual counts, fifty sheets with twenty-five circles each had been drawn up and placed among both men and women, so that circle by circle could be marked off for each tasbih completed, in contrast to the old system of counting with almonds. Participants took care of their own counting, until all the circles were marked off. The recitation completed, a du‘a was recited for the desired purpose. Then people rose to recite their namaz and to socialize; as usual, the event concluded with a sumptuous dinner, after which people quickly dispersed.

In this recitational event, no one stood out in any way; attending it was simply to reinforce the bond of mutual support that can always be activated among members of the community. In its own way, each of the four assemblies adds profoundly and significantly to this support, invoking shared ways of reaching God and shared means of coping with present-day life situations.

| • | • | • |

From Home to Mosque

This shared religious life appears essentially private, personal, and deeply conservative. The prime constant in this experience has been the home domain, although not in the sense of a specific home, since families readily move, and not in the sense of a specific urban area, since there are no signs of a South Asian Muslim quarter emerging. At the same time, the Muslim sense of community and, even more so, the sense of religious identity, has increasingly been extending beyond the home. The two main mosques in Edmonton, the one originally Arab and the second South Asian, reflect a gradually evolving sense of community, serving less as “sacred space”[17] than simply as loci for religious observance. The mosque is also the place where South Asian Muslims are today negotiating a communal identity that has both religious and sociocultural facets. This is evidenced in the way they selectively attend both mosques on different occasions. For instance, for ‘Id prayers many Pakistanis go to the original al-Rashid Mosque, with the aim of joining in one single Muslim congregation on ‘Id day, as they do in their homeland.

Notable is the participation of women in mosque worship, a practice pioneered by Arab Muslims and now practiced by South Asians, although in their homelands, mosques are attended only by men. Another Western innovation is the use of the mosque basement for community “functions”—and, of course, for children’s religion classes. The significance of participation becomes obvious if one compares such centers of Muslim worship as the Shi‘a imambara (or imambargah) or, even more so, the Isma‘ili jama‘tkhana, where women, and thereby children, participate in complementary roles as fully as men, so that for these Muslims their centers have become truly a community space.[18]

Increasing mosque activity no doubt reflects a recent and slowly growing trend toward solidifying and projecting a collective Muslim identity in the public domain, while also negotiating ethnocultural and linguistic differences vis-à-vis the universalizing thrust of transnational Islamic movements. Muslim Canadians themselves, however, often debate and deplore the fact that they are not “well organized” as a community.

Where South Asian Sunnis have constituted themselves into public community groups, it has been as narrower linguistic, regional, and national associations, such as the largely Punjabi-speaking Pakistani Association of Alberta. On the other hand, Urdu speakers, who hail from urban areas across the Indian subcontinent, lack a national focus in addition to a specifically Islamic one.[19] Individuals and families also express themselves through association with earlier and differently defined communities of Muslims—the Muslim Student Association; its parent organization, the Islamic Society of North America; a Muslim youth or women’s group; a Sufi group; a mosque association. Over their history in Canada, self-identification for Muslims has ranged within a universe extending from the single family to the umma of all Muslims; Muslim self-expression can therefore draw from anywhere in this rich reference base.

A gradual shift toward the mosque as a center of identity has been taking place during the past ten years. With the establishment of the South Asian mosque, or “Pakistani masjid” (as the Markaz ul Islam is commonly called), a deep involvement in the building, funding, and running of the mosque has created a sense of solidarity among men, on the one hand, and women, on the other, of many families. Contributing to this solidarity has been the desire of families to strengthen the religious identity of their growing children by encouraging joint activities. Recitational assemblies, especially qur’ankhwani assemblies held after a death, are beginning to take place in the mosque. Out of respect for its sacred content, qur’anic recitation is done in the mosque’s area for worship, on the main floor for men and the balcony for women. Both men and women arrive individually and choose a sitting place on the floor, using the walls for back support; one or two chairs are provided for the infirm. The event proceeds exactly as in the home. Those who finish their reading sit quietly, silent or talking softly; some individually assume prayer position to say optional rak‘at preceding the regular namaz that will follow the completion of the qur’ankhwani. After prayer, everyone repairs to the basement, where an appropriate repast has been laid out by the hostess and her women friends.

Ayat-e-karima, too, is sometimes held in the mosque, so as to involve a much larger number of reciters. As in the home, women of the host’s family organize the event, but here with the help of friends who share the tasks of preparing the food and of telephoning a large number of people to recite, using a list that circulates for this purpose. What stands out is that women continue to manage these events even in the mosque.

Unlike qur’ankhwani and ayat-e-karima, the milad is held in the meeting area in the basement of the mosque, given the nonliturgical status of its texts. In this space, men and women are, beyond the cloakroom area, separated by movable screens acquired earlier to create separate classroom spaces for an Islamic school. In contrast to the home situation, the proceedings are under male leadership, including riwayat and individually recited na‘t. Na‘t are also recited by a group of children, mainly girls, but not by women.

The milad is concluded by a repast; but occasionally now another, more public, way is chosen to conclude a large milad by offering everyone a share of tabarruk (blessed food). Thus there are signs of a more “public” or communitarian hue in these mosque events. On the other hand, they are hosted by—or often in the case of a death, on behalf of—a particular family, just like the same events held in the home of such a family. The issue of female participation in mosque basement activities is an evolving one, influenced on one side by the lack of precedent for women taking any active role on mosque premises vis-à-vis men, other than providing refreshments, and on the other by the recognition of women’s actual contribution toward the genesis and maintenance of this mosque.

Zikr does not have the community appeal to warrant being held in the mosque.

At this point, the frequency and importance of mosque events is minor as compared to home-based assemblies; it remains to be seen whether the desire to articulate a public Muslim identity will in the future supersede other, nonreligious facets of community identity, which up to now have continued to motivate South Asian Muslim bonding and self-expression.

| • | • | • |

From Performance to Participation

Placing the four assemblies in the historical perspective of three decades clearly indicates a movement toward the increased prevalence of the participatory, soundless, leaderless gathering of Arabic recitation. The growing preference for qur’ankhwani, not only in North America but also in Pakistan, probably reflects the impact of influential transnational Islamic movements. The general shift toward participatory, silent recitation appears moreover to be a function of two aspects of contemporary South Asian Muslim life in North America. One is a lack of performance resources, given the absence of traditional service professions, whether hereditary musical specialists, such as qawwals who perform mystical hymns for Sufi assemblies, or musically adept artisans and tradesmen. Second, the participatory assembly reflects the Canadian reality of a voluntary association among individuals who share a bond of religion and community activated only by mutual goodwill, leaving behind the ties of dominance and dependence that characterized social relationships in the homeland. The qur’ankhwani accurately represents this reality where everyone’s voice is speaking, but no one dominates. This contrasts clearly with the milad model, which projects dominance, submission, and temporal-spatial coordination within the group.

This trend represents a confluence of several trajectories, all of which are relevant to the larger issue of self-representation by South Asian Muslims in North America. First, identity is asserted vis-à-vis the West and in the face of its perceived “threat to valued social relationships” (Metcalf 1989) through an acting out of those relationships, reinforcing them by means of the shared verbal articulation of religious identity. Second, space is functional. Structural spatial expression of Muslim identity resides in the mosque, the processual spatial expression of Muslim identity is the qibla, and the social expression of family and gender relationships is the home. Finally, linking all three in dynamic action are the Word and its articulation, embodied in both the ritual of prayer and of the recitational assembly. Ritual prayer serves to universalize; recitational assemblies, to actualize the particular community of South Asian Muslims in Canada.

Seen in a wider context, the life of the four recitational assemblies forms a salient part of the unique and dynamic process of this Muslim community’s creating itself in the West. Its primary action has been to focus self-expression inward in order to articulate community identity to its own members, largely disregarding the presence of a larger society of outsiders. But as their sense of community has strengthened, the focus of self-expression is expanding toward self-representation vis-à-vis the larger society. Recitation, too, is affected by this shift, but it remains to be seen how South Asian Muslims transform the living Islamic Word as they move from adapting Western space to Muslim uses toward the creation of a Muslim space displayed to non-Muslims in the West.

Notes

1. This paper is drawn essentially from the life involvement of one who is both an outsider and insider among Muslims in Canada, a socially entrenched participant and translator across the margins. Its focus is on Muslims who have become, over the years, more like family members than friends, and what I write must reflect their sense of self-representation. My collaborators’ wish to stay outside this text accounts for the absence of the personal voices so attractive to read (see also Qureshi 1991). Special thanks go to Saleem Qureshi, Siddiqua Qureshi, Amera Raza, Atiya Siddiqi, Yasmeen Nizam, Zehra Hameed, Aqil Athar, Anisa and Nazir Khatib, and Najma Hossain. I am particularly grateful to Atiya Siddiqi, Anisa Khatib, Ansa Athar, and Yasmeen Nizam for sharing photographs of their homes. This chapter is dedicated to all of you!

2. Built in 1938 by a small group of Arab immigrants, Edmonton’s al-Rashid Mosque is the oldest in Canada. The newly built al-Rashid Mosque was opened in 1982. Today, the original small building has been moved to the historical site of Fort Edmonton. The Markaz ul Islam was opened in 1986.

3. For a discussion of basic concepts in South Asian Canadian community formation, see Qureshi 1983.

4. “The whole world is a masjid [mosque] for you, so wherever the hour of prayer overtakes thee, thou shalt perform the salat and that is masjid” (SahihMuslim 1977, vol. 1, ch. 194, no. 1057, p. 264; see also Samb 1991: 645).

5. The classical formulation is by Ghazali (Macdonald 1901–2; see also During 1988).

6. Qur’an, suras 109, 112, 113, 114.

7. Ibid., sura 112.

8. Ibid., sura 2:255.

9. In Shi‘a homes, names include members of the Prophet’s family (‘Ali, Fatima, Hasan, Husain), and pictures of their tombs at Karbala (Husain) and Najaf (‘Ali).

10. If disabled, a Muslim can recite a namaz without the gestures, just as dry cleaning can be substituted in ablutions (wuzu) if water is unavailable. Flexibility vis-à-vis ritual observance is characteristic of Islam and clearly serves to facilitate individual observance.

11. Despite the highly musical presentation, the term singing is inappropriate, since Islamic tradition does not approve of music in association with religious expression.

12. An informal alias for milad is auraton ki qawwali (women’s qawwali)—that is, a women’s equivalent of the (male) Sufi devotional assembly convened for listening to the performance of mystical hymns (Qureshi 1995).

13. Also chosen sometimes for repeated recitation are the words of the first qul, for which the appropriate number is 11,000 times. The practice of undertaking a fixed number of repeated repetitions is collectively termed wazifa.

14. The term khatam-e-qur’an (completion of the Qur’an) is also used for qur’ankwhani (see, e.g., Werbner 1990).

15. For example, during menstruation.

16. All qur’anic translations are taken from Yusuf Ali 1986.

17. In my experience, the term sacred does not resonate positively with Muslims.

18. My long association with both the Shi‘a and Isma‘ili communities leads me to think that their prior experience as endogamous minority groups (especially in East Africa) may have endowed them with an institutional religious life that furthered their adaptation and self-definition in Canada. The swift establishment of thriving imambaras and jama‘tkhanas after the two groups emigrated from East Africa contrasts strikingly with the very gradual establishment of South Asian mosque activities. Also striking is the fact that before the substantial immigration of Khoja Shi‘as from East Africa, South Asian Shi‘a religious life in Canada was not more publicly organized than that of South Asian Sunnis, possibly because of low numbers. See Schubel, this volume.

19. In Alberta this is exemplified by the now-dormant Urdu Muslim Cultural Association. The more recently established Bazm-e-Sukhan is explicitly secular and includes anyone interested in Urdu culture.

Works Cited

Abel, A. 1965. “Dar-ul Islam.” In The Encyclopedia of Islam, ed. B. Lewis, C. H. Pellet, and J. Schacht, 2: 127–28. Leiden: Brill.

Akbar Warsi, Khwaja Muhammad. N.d. Milad-e-Akbar. Delhi: Ratan.

Durkheim, Emile. 1938. L’Evolution pédogogique en France des origines à la Renaissance. Paris: Felix Alcan.

During, Jean. 1988. Musique et extase: L’Audition mystique dans la tradition soufie. Paris: Albin Michel.

Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

Grabar, Oleg. 1983. “Symbols and Signs in Islamic Architecture.” In Architecture and Community: Building in the Islamic World Today, ed. Renata Holod, pp. 25–32. Aga Khan Awards for Architecture. Millerton, N.Y.: Aperture.

al-Hujwiri. 1911. Kashf al-Mahjub. Translated by R. A. Nicholson. Gibb Memorial Series, no. 17. London: Luzac. Reprint, London, 1959.

Jones, Dalu. 1978. “The Elements of Decoration: Surface, Pattern, and Light.” In Architecture of the Islamic World: Its History and Social Meaning, pp. 144–75. London: Thames & Hudson.

Macdonald, Duncan Black. 1901–2. “Emotional Religion in Islam as Affected by Music and Singing, Being a Translation of a Book of the Ihya Ulum ad-Din of al-Ghazzali.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1–28, 195–252, 705–48.

Metcalf, Barbara D. 1989. “Making Space for Islam: Spatial Expression of Muslims in the West.” Proposal for SSRC Conference, Boston, November 1–4.

Moravia, Sergio. 1976. “Les Ideologues et l’age des lumières.” Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century 154: 1465–86.

Ong, Walter J. 1958. Ramus: Method and the Decay of Dialogue. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Samb, A. 1991. “Masdjid.” In The Encyclopedia of Islam, ed. C. E. Bosworth, E. van Douzel, B. Lewis, W. P. Heinrichs, and C. H. Pellet, 6: 644–707. Leiden: Brill.

Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt. 1972. “Indo-Muslim Religious Music: An Overview.” Asian Music, 15–22.

——————. 1980a. “India, Subcontinent of: IV Chanted Poetry, V Popular Religious Music, Muslim.” In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 9: 143–47. London: Macmillan.

——————. 1980b. “Pakistan.” The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 14: 104–12. London: Macmillan.

——————. 1981. “Islamic Music in an Indian Environment: The Shi‘a Majlis.” Ethnomusicology 25, 1 (January): 41–71.

——————. 1991. “Marriage Strategies among Muslims from South East Asia.” In Muslim Families in North America, ed. E. Waugh, S. Abu-Laban, and R. B. Qureshi, pp. 185–212. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press.

——————. 1995. Sufi Music of India and Pakistan: Sound, Context, and Meaning in Qawwali. 1986. Reprint. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt, and Saleem M. M. Qureshi. 1983. “Pakistani Canadians: The Making of a Muslim Community.” In The Muslim Community in North America, ed. E. Waugh, B. Abu-Laban, and R. B. Qureshi, pp. 127–48. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press.

Sahih Muslim. 1977. In Al-Jami‘-us-Sahih by Imam Muslim, trans. Abdul Hamid Siddiqi. 4 vols. New Delhi: Kitab Bhavan.

Shaw, Alison. 1988. A Pakistani Community in Britain. London: Blackwell.

Tomlinson, Gary. 1993. Music in Renaissance Magic: Toward a Historiography of Others. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Werbner, Pnina. 1988. “‘Sealing’ the Koran: Offering and Sacrifice among Pakistani Labour Migrants.” Cultural Dynamics 1, 1: 77–97.

Yusuf Ali, Abdullah, trans. 1986. The Holy Quran: Full Arabic Text, Roman Transliteration and Translation. Lahore: Sheikh Muhammad Ashraf.

3. “This Is a Muslim Home”

Signs of Difference in the African-American Row House

Aminah Beverly McCloud

Muslims over history have varied widely in their cultural lives. They have, however, generally shared certain practices dependent on space. Muslims’ submission of their will to God ideally reappropriates space and reorganizes temporality. Salat (formal prayer) requires space both physically and mentally. Fasting makes demands of mental and spiritual space, while altering temporality. The Hajj demands its space and time. In salat, for example, boundaries are formed when the prayer space is isolated. The calling of the adhan and the iqamah signal movement from one reality to another as the Muslim and Muslimah stand before allah. In salat, the individual merges with the worldwide (and local) umma in a time for God that is distinct and unbounded. Both the practical needs of ritual and the profound juncture of the coterminous nature of the time and space of salat with the time and space of the world have a fundamental influence on space.

This essay first briefly describes the main Muslim communities and their congregational spaces in Philadelphia and then turns to a discussion of the city’s African-American Muslim homes. Muslims make these homes, built on standard models, into a distinctive “Muslim space” through signage, decoration, and practice.

| • | • | • |

The Philadelphia Communities and Congregational Space

Philadelphia has been a microcosm of Muslim activity at least since the 1940s. Most Islamic groups in the United States either have members living there or some ties with residents. By the middle of the 1970s, numerous Muslim communities were evident in Philadelphia, among them the Moorish Science Temple of America (1913), the Ahmadiyah movement (1921), three Nation of Islam communities (1930), the American Muslim Mission (1980), the Darul Islam (ca. 1971), and several communities associated with the Muslim Student Association.

“Our divine national movement stands for the specific grand principles of Love, Truth, Peace, Freedom, and Justice,” the Moorish Science Temple’s statement of belief begins. “It is the great god allah alone, that guides the destiny of the divine and national movement” (Ali 1927). The community expect “the end of tyranny and wickedness” against African-Americans and seek to connect with their Muslim heritage in general and with the descendants of Moroccans in particular. They identify the qur’anic kufars (disbelievers, or the ungrateful) as the European-Americans, who face imminent destruction as a result of their apparent disbelief and unaccountability while engaging in evil conduct. They understand the nature of reality as spiritual and human existence as co-eternal with the existence of time. They believe that the Christianity taught by European-Americans was designed to enslave Africans, and they regard heaven and hell as conditions of the mind created by individual deeds and misdeeds.

Moorish Science members usually meet in a designated house in a room painted beige or eggshell, with neatly ordered rows of chairs on an uncarpeted floor polished to perfection. In one house I visited, all the chairs faced a small stage with a podium, behind which were seven chairs signaling some persons of importance. On the wall behind the stage were nicely framed portraits and documents: Noble Drew Ali’s mother dressed in white, with a long white veil; Noble Drew Ali by himself, looking regal; a charter for the community; and a set of bylaws. All the other walls were bare, and the only other fixture was a red flag with a green five-pointed star in its center. The sect offers members a space of neatness, cleanliness, and order.

The Ahmadiyyians, who originated in the Indian subcontinent in the late nineteenth century, assert that God is active in this world, determining and designing the course of events. They hold that there should be a living relationship with God, from whom revelatory experience is still possible. Because of this belief, other Muslims have accused them of denying the finality of Prophethood (cf. Haider, this volume). Ahmadis do, however, believe in the Oneness of God, observe the prescribed prayers, fast during the month of Ramadan, pay zakat, and perform the pilgrimage to Mecca. They also uphold the Al-Hadith (Friedmann 1989). They are active missionaries, and their journals, The Review of Religions and The Moslem Sunrise, have been widely used.