The Queens Muslim Center

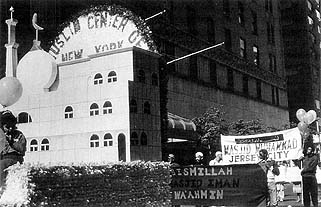

The mosques that float down Lexington Avenue may be recognizably famous structures such as the Dome of the Rock or they may be prototypical mosques in high architectural style. However, the fourth mosque float in the Muslim World Day Parade in 1990 represented the future Queens Muslim Center. This float is the point of departure for my inquiry into the nature of storefront mosques (fig. 39). The float is the only currently realized form of that mosque, which otherwise exists only as a hole in the ground in Flushing in the Borough of Queens.

Figure 39. The 1991 Muslim World Day Parade: Float of the Queens Muslim Center, with sign of the basmala (In the name of Allah, the compassionate, the merciful). Photograph by Susan Slyomovics.

The Queens Muslim Center was founded in June 1975 by Hanafi Sunni immigrants from Bangladesh, Pakistan, and India, in a rented apartment on Forty-first Avenue in Queens. The center is situated in the well-to-do middle-class neighborhood of Flushing, where the other predominant ethnic group is the flourishing Chinese community, estimated at seventy thousand strong. In 1977, the center was incorporated as a nonprofit tax-exempt institution, and by 1979, members had purchased a one-family house for $75,000 in cash. The adjacent house was purchased shortly afterward, and the two structures were razed for the new building. Groundbreaking for the new building took place on May 21, 1989. Photographs of the event prominently feature the presence of the imam of the Ka‘ba, Sheikh Saleh bin Abdullah bin Homaid of Saudi Arabia, flanked by then Mayor Edward Koch.

While awaiting the completion of their new structure, the members meet in a two-and-a-half story, gable-roofed house located around the corner at 137–63 Kalmiah Street. The temporary quarters of the Muslim Center has room for only two hundred members. The carved wooden door leads to an enclosed porch with shelves for storing shoes and a bulletin board for written notices. From the porch, a staircase leads to the upstairs women’s section. The downstairs is completely opened up, except for the kitchen wall entrance. The interior is carpeted and strips of tape orient the worshipper to Mecca. A pulpit made from kitchen cabinets and two wooden steps surmounted by a simple flat, wooden domelike ornament creates a minbar (pulpit or seat). Markaz (“The Center”), the magazine published by the Queens Muslim Center, describes a new building with room for five hundred and fifty people to pray in the main mosque, outside halls with room for one thousand six hundred people, another community hall seating four hundred, a kitchen, an Islamic school, and a gymnasium offering lessons in martial arts and the Qur’an. When it is finished, the Muslim Center will be an instance of successful transition from rented apartment to purchased house (both of them makeshift “storefront” expedients) to architecturally purposeful mosque and community center complete with designed dome, crescent moon, and minaret, the kind of mosque now typically preferred in the diaspora (cf. Haider, this volume).

The Queens Muslim Center embodies the aspirations of many, although not all, Muslim communities in New York City. These are best articulated by Levent Akbarut in “The Role of Mosques in America,” an article written for The Minaret, a widely circulating newspaper based in East Orange County, California, and excerpted in Markaz (1990). Akbarut argues that the American mosque, in contrast to mosques in the countries of origin, needs to be a school, because urban schools are substandard; a community center, because the streets are dangerous; and a locus of political activity, such as voter-registration drives, so that Muslims will have a say in the decision-making processes of this country (cf. Eade, this volume). Quoting a saying, or hadith, from Al-Bukhari, the author acknowledges that “a mosque within the confines of four walls and a ceiling is not a requirement for a Muslim community to offer prayer, because God has made the whole earth a sanctuary for worship.” Why then, he asks, did the Prophet build a mosque during the Medinan era? The answer is that the mosque functioned as a center of Islamic affairs and organization and thereby nurtured and sustained the Islamic effort. This example should be kept in mind by Muslims seeking to establish Islam in America (Akbarut 1986: 10). What the author envisions is precisely what the Muslim Center in Queens hopes to achieve: not only a mosque, but a building that unmistakably declares what it is, as opposed to the unmarked Queens house that currently functions as a mosque.