8. A Place of Their Own

Contesting Spaces and Defining Places in Berlin’s Migrant Community

Ruth Mandel

In a mosque in Berlin, located in a cavernous, unheated former textile factory, now subdivided and shared by a dozen migrant families, a Turkish Sunni hoca (religious leader, teacher, or preacher) told me that he and many other migrants intend to remain in Europe until the last European Christian has converted to Islam. This vision of the transformation of Europe to a landscape populated with Muslims and ruled by Islamic law is not, however, the only one held by migrants from Turkey. For example, some of the minority Alevis from Turkey, in radical contrast, extol the virtues and tolerance of their newfound European homes. These two divergent visions of “place” have created in Kreuzberg—the so-called Turkish ghetto of Berlin—a highly variegated ecology of Muslim experience. For some, Christian Europe is a land of infidels, and most certainly experience religious hardship there. For others, Europe is, rather, a land of opportunity. In this essay, after describing Kreuzberg, I address the complex expressions of Islam among Sunni and Alevi migrants, and discuss some of the ways in which these expressions change as a result of migration.[1]

| • | • | • |

Demography, Zoning, and Square Meters

German discourse about the “foreigner problem” often claims that the high Turkish birthrate will eventually overwhelm Germans demographically, particularly given the negative birthrate among the native German population.[2] Berlin’s foreign population remains the highest in Germany. West Berlin experienced a decline in population over the fifteen years encompassing the early 1970s to the mid 1980s, with the number of residents falling from 2,268,718 in 1973 to 2,156,209 in 1986. However, West Berlin’s foreign population grew from 178,415 to 257,916, about 12 percent of the whole. Despite alarmist rhetoric, however, Turks in Kreuzberg made up only 19.3 percent of the quarter’s legal residents in 1983: of a total population of 139,590, 28.7 percent, or 40,025 residents, were foreigners, of whom 26,952, or 67.3 percent, were Turks. In the next three years Kreuzberg’s foreign population barely changed, standing at 40,087 in 1986, compared to 110,490 Germans (West Berlin Municipal Government 1986). By 1992, the population of West Berlin was 2,163,040. However, German/German unification drove the figure for the new, united Berlin up to 3,456,891 in 1992, of whom 3,070,980, or 88.8 percent, were German. Of the 11.2 percent who were registered foreigners in 1992, 138,738, or 36 percent, were Turks, who thus comprised 4 percent of the city’s total population.

There are far more Turks in Kreuzberg than official figures indicate, and their number would no doubt be larger but for restrictive zoning laws regulating the whereabouts of foreigners. These laws, enforced by the Ausländerpolizei (Aliens Police), identify three quarters of the city—Kreuzberg, Wedding, and Tiergarten—as off-limits to the least desirable foreigners (those from the Third World). These are the three districts with the highest percentages of Turkish residents, with 19.3 percent, 13.7 percent, and 10.2 percent respectively. This restrictive regulation has been only partially successful. Informal restrictive covenants effectively prevent foreigners from renting housing outside these three neighborhoods, forcing them to circumvent the zoning laws. Housing has thus been a perpetual problem for the Turks of Berlin, with people shifting among several occasional and illegal residences. A Turk may be registered with the Ausländerpolizei at an address in a quarter that is not off-limits, perhaps the home of a sympathetic friend or relative, while actually living in Kreuzberg in a flat legally registered to others.

Turks also suffer because of the legally required minimum number of square meters per inhabitant in every flat set in 1977 (Castles 1984: 79).[3] Turkish families commonly fail to meet this requirement, based as it is on German, not Turkish, habits. Turks resort, therefore, to some form of false residency registration. It is not uncommon for a Turkish family of, say, seven, perhaps including three generations, to live, eat, and sleep in two rooms. Turks often sleep on dösek, futonlike mattresses, laid side by side at night and folded up and stacked in a corner by day, when the room becomes the living and dining room.

A visitor usually can ascertain if indeed this is the sleeping arrangement in a Turkish home by the presence or absence of the telltale alarm clock on a low shelf of the requisite huge breakfront in this multipurpose room. (Many migrants work very early shifts on construction jobs or in factories and rely on alarm clocks to waken them at 5:00 a.m.). The breakfront is considered a highly desirable piece of furniture in migrant homes, and is used for displaying china, souvenirs, plastic flowers, family photographs—particularly wedding photos—and countless knick-knacks. In front of the sofa, often used for sleeping at night, there will generally be a long, low table, around which the family gathers for meals. Several adults and children might sleep side by side on the floor of one such room. Moreover, space can always be made for guests. Reactions from the Turks to the space requirement range from confusion to embarrassment, as they realize that they are being legally—and morally—sanctioned for what they take to be normal behavior.

| • | • | • |

Landscapes of Kreuzberg: the Structural, the Social Structural, and the Antisocial

It is no accident that Kreuzberg, the “Turkish ghetto,” is the least-renovated district in western Berlin. In the former West Berlin, it was surrounded on three sides by the Berlin Wall. Today, in Germany, Turkey, and indeed in many circles throughout Europe, the name Kreuzberg connotes a very specific set of images and associations, which revolve around its reputation as “Kleine Istanbul,” Little Istanbul. However, its notoriety was already established long before the Turks’ arrival in the 1960s, for Kreuzberg has been politically marked for centuries (cf. Spitalfields: Eade, this volume). In the seventeenth century, French Huguenot refugees found asylum there. In the nineteenth century, indigent, landless immigrants from Silesia, Pomerania, and eastern Prussia came in search of work. At the turn of the last century, the district served as home to industrial workshops and small factories, as well as to the workers employed in them. A particular form of building structure was erected to serve these working and living needs. This multilayered, structurally dense and complex configuration was known as the Hinterhaus (back/rear house, or building), designed around a series of Hinterhöfe (back/rear courtyards). This living/working arrangement distinctly delimited a highly stratified social ordering, in brick and mortar, of classes and functions. The rear buildings, unlike those in front, were built of plain brick, lacked direct access to the street and to sunlight, had no private toilets, and were invariably noisy and crowded.

Thus, although they lived in contiguous structures, different social classes experienced vastly different lifestyles. Large courtyard buildings, typically about six stories, opened up to secondary and sometimes tertiary and even fourth courtyard buildings. Sometimes an additional building might jut off one of the sides, or stand free in the middle of the courtyard; this might be a factory or workshop. The spacious sunnier apartments facing the streets were reserved for the wealthy workshop and factory owners. Often these apartments would consist of an entire floor of the building—in other words, the four sides of a square, constructed around the inner courtyard. The workers’ flats in the Hinterhäuser behind the main building and courtyard were smaller, darker (in an already dark city, with fewer sunny days than most in Europe) and hidden from street view.

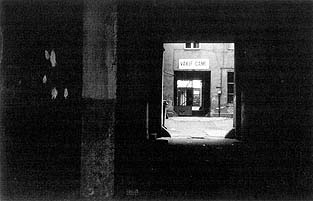

These are the buildings in which Berlin’s Turkish migrants typically live. Many of their mosques, community, and political organizations are located in such buildings as well (fig. 28). Today, most of the flats have been repeatedly subdivided and allowed to fall into disrepair. Although many façades, and some interiors, have been beautified in a public renovation project undertaken in Kreuzberg in the past decade,[4] in the courtyards beyond the often grandiose entrances, the inner Hinterhaus of run-down, dark, dank buildings remains. These façades are not decorated with elegant Stücken (decorative stucco reliefs) like the adjacent streetside buildings, but instead stand in quasi-ruin, occasionally still pockmarked with bullet holes from World War II.

Figure 28. A Berlin mosque seen through a Hinterhof courtyard. Photograph by Ruth Mandel.

For many migrants from Turkey, the space of the inner courtyards, where children play and adults socialize, defines their social life. Some apartment houses are known for the regional homogeneity of the residents. Upon entering some of these unrenovated apartment buildings, one is often confronted with the lingering odor of urine emanating from Aussentoileten, tiny shared “water closets” located in the stairwell between floors. In many, there is no central heating, no hot water, and only one cold-water tap. Coal dust in the air settles on clothing, under fingernails, and, of course, in the lungs.

The Germans who live in Kreuzberg are themselves among the powerless: elderly pensioners; alcoholics; the indigent; visual and performing artists seeking loft space for studios, theaters, or cinemas; or other members of counterculture groups, who fall into roughly two categories, the punks and the Alternativen, the latter being the remnants of the Acht-und-sechzigers—the “sixty-eighters,” an expression that refers to the politicized radical activists of the highly charged times surrounding 1968, now closely associated with the Green Party, health food, and communes.[5]

Although for many it is the thriving alternative scene that has lent Kreuzberg its notoriety, for others it is the presence of the Turkish Ausländer (foreigners)—people brought to Germany as Gastarbeiter (guest workers)—that defines Kreuzberg’s identity as Kleine-Istanbul. The large number of Turks who ride the subway into Kreuzberg have given it the sobriquet “Orient Express.” The train’s final stop is a few blocks from Mariannenplatz, a large park favored by Turkish women and families for picnics. Nicknamed Turken-wiese, the “Turkish pasture” or meadow, this park lies in front of a former children’s hospital, since transformed into Kreuzberg’s Künstlerhaus Bethanean, an artists’ center, often catering to the local Turkish community, which sponsors exhibitions, concerts, theater, and a Turkish children’s library. In addition, it provides studio space to local artists and housing and studio space for temporary foreign artists-in-residence. Mariannenplatz is a popular site for summer outdoor concerts and festivals—alternative art and music fairs, “foreigner festivals,” and the like. Political posters and notices of demonstrations are commonplace. Although Kreuzberg may no longer mark an international frontier, the Turks who live there regularly cross a perilous divide separating two different worlds. They navigate between their worlds, not only when they make the annual vacation trip to Turkey each summer (Mandel 1990), but daily when they leave the Turkish inner sanctums of their cold-water flats, their Turkophone families and neighbors, their Kleine-Istanbul ghetto to enter the German-speaking work world and marketplace, where the characteristic economic relations between “First” and “Third” worlds are linguistically, socially, and cultural reproduced.

| • | • | • |

Little Istanbul

Both Sunni and Alevi migrants from Turkey take great care to prevent the moral contamination that they believe threatens them in Germany particularly in the form of haram (forbidden) meat, pork. Helal (that which is obligatory or permitted) dietary laws, nearly unconscious in Turkey, have moved to the forefront of concerns in gurbet (exile). Clever entrepreneurs have used the fear of haram to their advantage and have had great success with their helal industries, which sell everything from “helal” sausage to “helal” bread. Elsewhere (Mandel 1988), I have discussed the explicit association many Turks make between pork and promiscuity, which lends still greater fervor to the conspicuous avoidance of German food, restaurants, grocery stores, and butchers. The result has been a proliferation of shops catering nearly exclusively to Turks. Like the British fish-and-chips shop pictured in figure 2, Turkish food shops in Germany typically put the word helal on their signboards, or even post a certificate guaranteeing helal meat.

One of the central Turkish commercial districts is near Schlesisches Tor, the terminus of the subway. The area boasts dozens of Turkish-owned and -operated businesses, carrying Turkish products for Turkish customers: bakeries, tailors, coffeehouses catering exclusively to Turkish men (for card-playing, gambling, drinking), butchers, greengrocers, grocery stores, restaurants, video rental shops, and Turkish travel agencies, some of which also perform several other functions, such as those of insurance agency, realtor, and translation bureau. There is a storefront office housing the Turkish branch of the German Social Democratic Party. Several “Import-Export” shops sell items such as the coffee cups and tea glasses favored by Turks, colorful shiny fabrics, assorted knickknacks, electronic goods, music cassettes, and jewelry. Some of these shops do an excellent business in items for the dowry and baslik, the brideprice.

German-owned shops close promptly at the legal time, whereas Turkish shops have gained a reputation for staying open late. This is widely appreciated, not only by Turks, but by working Germans as well. Furthermore, Turkish greengrocers have acquired a reputation for produce of much higher quality than that offered by their German counterparts. For example, the greengrocer (manav) I patronized received shipments of good fresh produce twice weekly from Turkey. Many Turks in Berlin, and, increasingly some Germans as well, shop at the weekly Friday Turkish open market (pazar) at the Kottbüsser Tor neighborhood of Kreuzberg, winding several blocks along a canal. Stands sell produce, dairy products, meat, flowers, bread, and spices, as well as olives, feta cheese, Turkish tea, and pork-free Turkish sausages. A major social event, this weekly outdoor market is reminiscent of markets held in Turkish towns and cities. Shoppers exchange news, gossip, glances, recipes, and information, and the mood is one of noisy chatter, bargaining, and busyness. Not far from the market are several mosques. In recent years, attendance at mosques has escalated, and after Friday prayers, the streets around them are filled with Turkish men, many identifiable as Muslim by their skullcaps or hats and characteristic beards.

The oldest mosque in Berlin is not in the heart of Kreuzberg, however. Founded in the nineteenth century, Turk Sehitliki Camii served Berlin’s small Muslim community as a house of worship and a cemetery, now overflowing to a huge adjacent area. Even so, many prefer to repatriate bodies for burial “at home.” Figure 29 shows the mosque’s minaret rising above the burial ground.

Figure 29. Minaret at Berlin’s oldest mosque and cemetery complex. Photograph by Ruth Mandel.

Islamic organizations and parties coexist with the mosques and businesses in Kreuzberg. For example, Refah (Prosperity), Turkey’s main religious party, maintains an active storefront shop and local headquarters in the heart of Kreuzberg. It looks like a bookshop from outside, its windows stocked with books and pamphlets in Turkish on subjects like “Marriage and Wedding in Islam”; “Youth and Marriage: A Marriage Guide”; and “How to Pray” (a manual for children). Juxtaposed with this literature are banners and busts won in sports competitions by the organization’s teams. Inside, a few young men may be milling around drinking tea in the book-filled front room, some wearing Refa lapel pins. A heavy curtain separates the front room from an inside room, which is set up for meetings and lectures, with a large Turkish flag in the front.

| • | • | • |

Gurbet: Cinema and Exile

Given this physical setting, how do Turks view their life in Germany? In the mid 1980s, a very popular film called Gurbet told the story of the religious, obedient daughter of a migrant family who always wore total “Islamic” dress (kapali), complete with large head scarves and long coats. She associates with Germans, however, who introduce her to liquor, drugs, and miniskirts and rape her. Meanwhile, one of her brothers has become involved with organized crime and is shot. Another brother tracks down the wayward sister; the girl, afraid of what he will do to her, jumps from the top of a high building and kills herself. Germans are made out to be cold, indifferent, calculating, inhuman, and abusive as employers of Turkish workers. They are immoral and sexually promiscuous. The close-up camera work focuses on crucifixes, the breasts of braless German disco dancers, thighs of German girls in miniskirts, and the like. The entire migrant enterprise is portrayed as fraught with tragedy and shame. The Turks do ultimately return to Turkey, but they return either in their coffins, or bitter in mourning for their dead relatives, cursing the day they left their homeland and villages.

Frequent exposure to movies such as this surely play a role in the Turkish viewers’ fears of and attitudes toward Germans. The fear of foreignness reflected in Gurbet is, however, anything but novel. Rather, it is only a new variation of an old theme. Hundreds of similar movies made in Turkey depict nearly identical narratives; the only difference is that Istanbul, instead of Germany, is portrayed as the corruptor of innocence. The ratio expressing the cultural topography is: Turkish village : Turkish city :: Turkey : Germany.

The same values of home, safety, morality are associated with either one’s village or one’s homeland, and stand in sharp contrast to the immorality of gurbet, represented either as the evil city or Germany. Turkey is the village, and Germany the city writ large. Yet Germany is not Turkey and offers constraints and opportunities that shape religious and ethnic life in ways that may also be seen as positive.

| • | • | • |

Expressions of Islam Abroad: Alevis and Sunnis

For the migrants from Turkey, well-entrenched networks sustain an international movement of personnel that fosters what are seen as competing Turkish and Islamic identities. For example, a bilateral agreement permits the Turkish Ministry of Education to send Turkish teachers to the Federal Republic of Germany to teach public school courses in Turkish history, culture, and civics. These teachers have generally tended to be staunch supporters of Kemalism—by definition, laicists.[6] A lively competition for control of the indoctrination and education processes of the second generation has thus ensued, compounded in 1987 by a major scandal linking key officials in the Turkish government to Saudi Arabian funding of the export of Islamic religious education to Germany.

Many Turks in Germany already were observant Muslims before migrating. However, for others it is the foreign, Christian, German context that provides the initial catalyst for active involvement in religious organizations and worship. In part, this increased identification with Muslim symbols and organizations is a form of resistance (on women and head scarves, see, e.g., Mandel 1989: 27–46) against the prevailing norms of an alien society commonly perceived of as dangerous, immoral, and gavur (infidel).[7] The migrants’ marginality provides the context for explicitly religious expressions and concerns that might not be relevant were they part of society’s mainstream.

Migrants also have opportunities to participate in organizational, preaching, and educational modes that would be illegal in Turkey. All are free from legal constraints on religious activities. The minority Alevis in particular find in the diaspora an environment conducive to expressing their Alevi identity, free from what they perceive as the pressures of a repressive Sunni-dominated order in Turkey.

Repatriated Sunni migrants in Turkey frequently told me that it was in Germany that they had become religious (dinci,dindar); only there had they begun wearing head scarves and attending mosque. Anti-Alevi prejudices migrate along with Sunni Gastarbeiter. Direct contact may overcome some of these, but friendships between the two groups are generally thought of as exceptional. Sunni beliefs about the alleged immorality, ritualized incestuous practices, and impure nature of the Alevis are deeply ingrained. The second-generation young people thus rarely marry outside sectarian boundaries.

| • | • | • |

Head Scarves and Alevis

The official government position is that the majority, perhaps 80 percent, of Turkey’s nearly sixty million citizens are indeed Muslim and identify on some level with the Hanefi branch of Sunni Islam. However, it is estimated that approximately 20 percent of the population, some ten million, adhere to the “heterodox” sect of the Alevis.[8] Although the Alevis share many dogmatic tenets with Shi‘ism, they do not identify with the Iranian Shi‘a, the Syrian ‘Alawites, or any other Shi‘a group. For decades in Turkey, the Alevis have had reputations as leftists and communists of various persuasions.

Many, if not most, of the anti-Alevi allegations revolve around morality and women. In Germany, one of the symbolic markers of religious affiliation that has grown in importance is the head scarf. The closer the scarf is to a totally covering veil, the higher its piety/prestige value. Therefore, one mode used by observant Sunnis to differentiate themselves from the Alevis is by the type of headgear one wears or has one’s wife and daughter wear, since a woman’s public appearance directly reflects on her male relatives. Many observant Sunnis are offended by Alevi practices. They speak disparagingly of Alevi women and girls parading about without this symbolic barrier of cloth, an ostensible protector, announcer, and definer of morality.

Alevi women in Germany frequently do not wear scarves. This is especially true of those who were born in Germany or who came as children. Their middle-aged mothers might wear kerchiefs (loosely tied, revealing hair) on the street, but never a complete three-layer semi-veil. This lack of concern for scarves resonates with the Alevi belief system, which privileges inner qualities over external practices and display such as dress. Indeed, the Alevis, like the Shi‘a generally, practice taqiya, dissimulation (in relation to sectarian affiliation). Following the doctrine of dissimulation, Alevi women need not keep their scarves on to keep their identity intact.

Interestingly, the act of shedding the scarf, an act not particularly significant to Alevis, becomes imbued with meaning for some Germans. This is because the Turkish women’s head scarf has entered German discourse as an important symbol, signifying the will and capacity to integrate (cf. Bloul, this volume). Conservative advocates of repatriation point to the head scarves as proof that Turks are fundamentally incapable of fitting into German society. Others, some of whom might defend the continued presence of Turks on German soil, see the scarf as a marker of backward, patriarchal oppression of women, and try to persuade the wearers to change in order to fit in. A minority among this latter group of German liberals are aware of the differences between Sunnis and Alevis. They are quick to appropriate the Alevis for their own political project and to use them as an example of Turks who “successfully integrate.” Thus, both wearing and not wearing scarves are political and polysemic statements in both German and Turkish societies (Mandel 1989).

| • | • | • |

Alevis and Sunnis: Separate Spaces in a Shared World

The migrant diaspora context does little to alleviate the already deep-set antagonisms, suspicion, and animosity between Sunnis and Alevis. In fact, if anything, many Sunnis become still more hostile toward Alevis. The unchecked politicization of mosque-centered religious preaching that proliferates in Germany is often directed against infidel immoral Germans, communists, and, by extension, Alevis. Abroad, located as they are in an environment that is characterized as haram, it is easy for anti-Alevi Sunnis to make the association that these heretical Muslims would not only join forces with Germans of the political left but adopt German moral codes as well. Berlin supports dozens of mosques, which focus sectarian identity. The Mevlâna mosque (fig. 30), for example, is located in a modern Berlin-style high-rise, shared with numerous doctors’ practices and residential apartments. Named for the Mevlevi dervish order founded by Jalal ud-din Rumi, a medieval Persian poet who settled in Konya, this mosque is associated with Sufi devotional practices. The signboard depicts Rumi’s mausoleum in Konya.

Figure 30. Concrete apartment/office block with names of residents (several doctors’ practices) and the Mevlâna Camii mosque, Berlin. Photograph by Ruth Mandel.

The Sunnis and Alevis generally live and operate in very different social circles. It is rare for individual Sunnis to be invited to an Alevi wedding or circumcision celebration—or vice versa. When a Sunni friend of mine in Berlin was asked by an Alevi friend and neighbor to be the kivre (circumcision sponsor; godfather) of his son, the novelty generated quite a bit of gossip. Alevis try to do as much business as possible at Alevi-owned establishments, a preference reinforced by regional identity for both Alevis and Sunnis. In Berlin in 1990, for example, a large group of Alevi families collectively pooled their resources in order to open a private wholesale store. Some claimed that they had been excluded from similar Sunni-owned ventures and therefore wanted their own. Both in Istanbul and in Berlin, I often was astonished at the extent and intricacy of how the Alevi networks functioned. Particularly in Turkey, since Alevis are the minority group, they are more sensitive than Sunnis to the subtle clues and signs that indicate who is who.

Alevis may conceal their identity, as did Haydar, a young Alevi man from eastern Turkey in trying to appeal to Sunni customers in his video shop. In 1985, approximately seventy Turkish video rental shops in West Berlin catered to tens of thousands of clients demanding new films several times a week.[9] At Haydar’s shop, the clientele ranged from young children not tall enough to reach the counter to fatigued working people on the way home from work to single young people congregating to socialize. Relatives and friends of the shop’s owner often dropped in, including several young male cousins and their friends, who would sit in the shop learning to play the lutelike saz, associated with Alevi mystical poetry, under Haydar’s tutelage. At times when he had to work at a second job, his wife, Havva, ran the store.

During the Şeker Bayrami holiday (celebrated at the end of Ramadan), Haydar had a bowl of the conventional candies to give to customers, as well as limon kolonyasi (lemon cologne) to squirt on their hands.[10] Although Haydar offered me some candy, he and his cousins refused to partake of it, his nephew explaining, “We don’t celebrate it—it’s not our holiday. Kurds don’t observe Şeker Bayrami.” When I asked, he admitted that he had meant Alevis, not Kurds. Perhaps he thought that I, a foreigner, might know what Kurds were but not Alevis.[11] He may have been testing me; or, he may have preferred not to implicate himself and his relatives as Alevis.

The very act of providing Bayram candy for Sunni customers was telling. Not only would it please them, it was a good business practice. Consonant with the Alevi practice of dissimulation, Haydar could “act” Sunni; he feared that had he not tried to “pass,” he might have lost customers, who would have taken their business to a Sunni.

| • | • | • |

From Ritual to Revolution

Alevi and Sunni attitudes to their stay in Germany seem to differ. More Alevis appear to stay. Not only have Alevis left behind their minority religious status, they also have left a particularly difficult political and economic situation. Many are from the poor eastern, Kurdish regions that have been under martial law and suffered protracted civil war. Thus Alevis tend to see themselves as staying in Germany indefinitely. They are more apt than Sunnis to invest in nicer and costlier flats, while Sunnis might stick to a slum and a simple diet of beans, rice, and bread in order to save their money for investment in property or a business in Turkey. I contend that Alevis, by virtue of their historical tenacity in the face of centuries of repression, massacres, and discrimination, see in Germany, not a land of infidels whose influence is to be feared and avoided, but rather a land of opportunity and tolerance, neither of which they have found in Turkey.

Today, in Europe, several Alevi groups conceive of themselves in explicitly political—and national—terms. Perhaps the most extreme, a group calling itself “Kizil Yol” or Red Path, advocates the founding of “Alevistan,” or a nation of Alevis. Taking its model from the struggles of Kurdish separatists for the establishment of an independent Kurdistan, these followers of the Red Path are criticized by some on the grounds that Alevilik (Aleviness) is a religion, not a nationality. Most Alevis would not support this nationalist expression of Alevilik, and Kizil Yol is far from representative. Nonetheless, the notion of “Alevistan” is compelling, for it suggests the emergence in the diaspora of a consciously discrete identity that gravitates around a fantastic center.

Thus, it is precisely because of their absence from Turkey and their presence in gurbet, in diaspora, that some Alevis have begun to refashion their identity. Moreover, this condition has afforded them the political and conceptual freedom in which to imagine a nation-state for themselves. In terms of notions of place, it is important to note the influence of the discourse of Western nationalisms, and particularly the idea of the nation-state. For what is perhaps the first time, Alevis have begun to conceptualize themselves in terms of place, in a jargon borrowed from the West—territory.

In Turkey, anti-Alevi repression is felt in multiple realms, in explicitly political activity, and also in the religious domain. In particular, the Alevi practice of their central communal ritual, the cem (pronounced “gem”), was until recently outlawed.[12] The cem is the secret communal Alevi-Bektasi ritual of solidarity and “collective effervescence,” involving song, music, and dervish trance dancing, as well as a reenactment of the martyrdom of Husain (cf. Schubel, this volume). As part of Atatürk’s secularization policies, a law enacted in 1925 closed down all tarikats—religious, often dervish, orders—and forbade their ceremonies and practices. Even prior to this ban, the Alevis were forced to practice the rite of cem in secret. The clandestine nature of the cem is not only suggestive of a restrictive and oppressive political and social climate but resonates as well with the dissimulation condoned and practiced by the Alevis. In addition, the ceremony itself reproduces an identification with the oppression and martyrdom of ‘Ali, Hasan, and Husain.

In this diaspora, the celebration of the cem ritual provides a collective grounding for displaced Alevis. Similarly, it offers a familiar and emotionally charged mytho-historical charter, providing and suggesting an associated code for conduct. In recent years it has been celebrated approximately on an annual basis, although in a novel form and setting. A cem that I attended took place in a run-down working-class district of Berlin whose population boasts a high proportion of foreign—primarily Turkish—residents. It was held in a large hall, deep in a complex of large, old Hinterhäuser (like that in fig. 28), now converted and rented out for discos, parties, and the occasional religious ritual.

This cem was attended by about three hundred people, fairly evenly divided among genders and generations. It was complete with the sacrificed animal, divided, cooked, and eaten together. All presented niyaz offerings of food to the presiding dede. Several musicians played the baglama, or saz, throughout the ceremony. After the emotionally charged dousing of the candles (for the twelve imams and martyrs) came the semah, a type of music and dance associated not only with the Alevis but with dervishes generally. There are many varieties of semah, and the men and women who rose to dance to saz music represented stylistic and regional variants. The music is highly rhythmic, begins slowly, then speeds up as the dancers enter a dervish, or ecstatic trance state.[13]

The ritual and the feast are geographically movable. The organizers had brought the proper decor and affixed it to the wall behind the pirs (who are members of holy lineages). This consisted of pictures of Ali, Hasan, Husain, the other imams, Haci Bektash, the Bektashi Pir Ulusoy, and, to be safe (again, dissimulation), there was a large portrait of Kemal Atatürk. Above all these hung the Turkish flag.

Not only did this Berlin cem occur in an unconventional space, the time continuum was radically transformed as well by the addition of a novel element: video. Three video cameras had been set up, with blinding lights, all operated by amateur cameramen. No one thought it peculiar or paid the cameras any heed. The multiple recordings of the ritual on videocassette offer new meaning to the concepts of participant, observer, and event. For example, a few days after the cem, I was in an Alevi home, and someone suggested they watch it on the VCR. It was put on, but after about five minutes the father of the family demanded that it be turned off. He could not tolerate the children laughing and playing in one part of the room and his cousins on the sofa next to him gossiping about what some of the people in the video were wearing. For him, the only way to watch it was to recapture the intensity and sober ambiance of the ritual itself.

Despite the warehouse environment and the foreign context, it is at events such as this cem that Alevi identity renews itself for the migrants and their children. Much of the novelty lies in the very composition of the group participating—for example, the juxtaposition of pirs from diverse regions of Turkey, all seated at the place of honor, the post, with the officiating dede—some of whom had only become acquainted with one another at the cem itself. Until very recently, such a cem probably would not, could not, take place in Turkey.[14] Yet in the diaspora, highly effective informal networks forge a community of a sort that has never existed at home, as it attempts to worship and celebrate in concert.

Conversely, in the diaspora context, some leftist Alevi activists have again reinterpreted the meaning of the cem. A young leftist Alevi man in Germany explaining the cem in terms of the progressive nature of Alevilik said to me, “Without women there can be no cem; without women there can be no revolution.” Thus, the cem becomes the metaphor and template for social change. Quintessentially polysemic, the cem emerges as a ritual act, either reactionary or revolutionary,[15] depending on the context and interpretation. In its very practice, then, it assumes historical importance as an expression and assertion of an identity that must struggle to survive against odds at home and abroad. In that assertion, historical meanings and relations are assimilated and reinterpreted in a new, contemporary context—for example, “revolution.”

Migrant Alevis have in many ways successfully reversed their hierarchical subordination to Sunni Turks. While steadfast in their Aleviness, they identify with and admire many aspects of German society that Sunnis find threatening. Modeling themselves on certain German, Western modes, they pride themselves on how modern they are, as opposed to the “backward” Sunnis. They point to what they see as their more “democratic, tolerant, and progressive” stance, and to the “marked” village clothing many Sunni women wear: flowing salvar pants, head scarves, and so on. Finally, Alevis tend to be more politically engaged in leftist politics and syndicalism than Sunnis, and, through such activities, have greater contact with Germans. This greater contact with Germans reinforces their self-image as “tolerant.”

The differences between Sunni and Alevi attitudes can be seen in the way the two groups speak of Germans. Alevis referring to Germans will say, for example, “They’re people, too,” whereas Sunnis tend to be critical and dismissive of Germans, commonly disparaging them as gavur. Although still peripheral with respect to Sunnis, the Alevis may be slightly less marginal than Sunnis in relation to mainstream German society. As a consequence of their greater acceptance of German ways and people, they have become more accepted by Germans than are many Sunnis. The status of Alevis is also raised in the eyes of Germans by the fact that they characteristically do not attend mosque, and perhaps also by some aspects of the practice of dissimulation.

While Alevis abroad are doubly marginal, with respect to both Germans and Sunni Turks, their relative position vis-à-vis Sunnis has undergone a transposition. In Germany, Sunni dominance has become less and less relevant as a reference point. Alevis had traditionally defined themselves primarily in opposition to Sunnis, and always in relation to them; now, in Germany, they have in some respects gradually replaced Sunnis with Germans as their salient other. Whereas some Alevis in Germany have taken advantage of Western freedoms to adopt a more inward, communal orientation, unfettered by past political and social constraints, others have opted for an ecumenical stance, and still others choose to dissociate themselves from anything they perceive as religious.

| • | • | • |

Conclusion: Toponomy, Almanyali, and New Identities

The migrants’ experience of Kreuzberg both derives from and helps to shape its physical reality. Ultimately, despite their presence in “Gavuristan,” the land of the infidel, surrounded by all sorts of things profane and haram, the Turks manage to create and define a world for themselves. The world they construct lies on frontiers ranging from culinary to linguistic, from sartorial to domestic. These markers serve as functional borders delimiting a new center, which, differentially and subjectively interpreted, defines the meaningful expressions of Turkish identity abroad.

This essay has been concerned with the ways migrants from Turkey fit into the existing urban social and physical structures, and have helped to refashion, challenge, and revalorize the German definitions. Paralleling the defining German nicknames “Little Istanbul,” “the Orient Express,” and “Turkish pasture,” some Turks have their own code names for parts of Berlin as well. Istambulis sometimes use the names of the Istanbul neighborhoods for functionally analogous neighborhoods of Berlin: “Caǧaloǧlu” for a section of Kreuzberg that has Turkish printers, publishers, and bookstores; “Bebek” for the elegant Grünewald neighborhood of Berlin; and Kreuzberg itself might be referred to as Turkey or Istanbul; and “Beyoǧlu” serves as the nickname for the main shopping district in Berlin; an old, out-of-commission covered train station, now converted to Turkish shops, advertises itself as “Türkische Bazaar.” An indoor shopping area in Kreuzberg calls itself Misir Çarşisi—Egyptian Market—the Turkish name for the famous spice bazaar in the old part of Istanbul.

The ability to name itself or be named by others is not the only measure of control over the construction of a community or the definition of group boundaries. In the process of creating and recreating itself, the community does so, on the one hand, in implicit opposition to the German context—in defiance of the official definition of Germany as a nonimmigration land, one implicitly unsuitable for pluralism—and, on the other, against pressures to assimilate. By redefining, or renaming parts of the German urban environment, these Turks are staking a claim and appropriating it for themselves—and on their own terms.

The extensive degree of commercial self-sufficiency is another way the migrants have recreated the place for themselves, and in their own terms. Thus, one need not know a word of German to buy insurance; rent a video; buy pide bread, olives, or helal meat; talk to a child minder at a day-care center; deal with a travel agent; and so on. Thus the motivation for many of the migrants to learn German remains minimal. In addition, the prevailing ideology that most everyone shares remains the “myth of return.” For many, if not most, migrants, Kleine Istanbul is not home. They dream of their final return to Turkey, plan for it, save for it, talk of it. And in their summer vacations, they rehearse it, returning for a month or five weeks.

When they arrive in Turkey, however, they are greeted with an ironic appellation; they are called almanyali, “German-like.” The dream of going home proves to be an impossible one, since they are no longer accepted as they once were. In fact, many migrants are relieved to return to Germany after disappointing summer trips. Once back “home” in Germany, they can find sympathetic friends with whom they can complain about this bitter experience, and recall that Germany is so much cleaner, more efficient, and the bureaucrats more honest. After a quarter century in Germany, the idealized dream of Turkey becomes distorted; in its stead, whether they are willing to admit it or not, Germany has begun to come to the conceptual fore.

In this new place, by their own actions and decisions, they are setting new precedents, as they project an agency of their own design, reshaping the Kreuzbergs of Europe into novel and heterogeneous communities. It is in the recognition of an alternately constructed center that the Turks are able to seek positive identifications. Paradoxically, however, this center is located in a peripheral place vis-à-vis Turkey, the original affective orienting center. Thus, the longer the migrants live in the “peripheral center,” the greater its prominence and the more of a competing threat it poses to the traditionally central role occupied by Turkey.

In the 1980s, the Turkish-German “second generation” came into its own as a resident “ethnic” group—albeit in a country that denies this categorical possibility. The likelihood of repatriation is rapidly diminishing for this young Turkish-German population, and the prospect of living their lives as Turkish-Germans in Germany has come to seem more normal to them. Many of them who attend vocational school and university will be productive workers in German society; others, who had the misfortune to be shuttled back and forth between Anatolia and Germany as children, are more marginal and are now bilingual but illiterate young adults. Some have joined Kreuzberg’s growing street gangs and have in that way become involved either in crime or in defending against neofascist Germans who assault Turks, or in both. In a sense, this defending of their turf by Turkish gangs symbolically affirms their right and intention to remain in Germany.

In this “peripheral center,” the Islamic dimension of Turkish life is far from a mere changeover from the migrants’ previous experience. For many, religious behavior and symbols are new or infused with new meaning, whether as a mark of the new ethnicity thrust on them, as a response to the change from rural to urban life, as resistance to German culture, or, for some Alevis, as a claim on that culture. The conceptualization of this space is anything but homogeneous, whether articulated as gurbet or as a potential dar al-Islam (House of Islam). Embedded within Kreuzberg’s variegated social ecology are the seeds from which alternative expressions of Islamic identities may bloom.

Notes

1. The information presented here reflects the rapidly changing situation in 1988–90. Some place names, statistics, and so forth, may therefore be out of date.

2. Germany’s highly restrictive abortion law, an important part of the Federal Republic’s pro-natalist policy, contrasts sharply with that of the former East Germany. In the “five new states,” eastern German women have been reluctant to accept the imposition of the anti-abortion policy by the west. This has been one of the most highly charged issues surrounding unification.

3. Bund-Länder-Kommission, Zur Fortentwicklung einer umfassenden Konzeption der Ausländerbeschäftigungspolitik (Bonn: Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Sozialordnung, 1982).

4. This citywide urban renewal project, International Bauaustellung, sought to dislocate as few people as possible and to allow residents to decide the nature of alterations. Thus, poorer residents were able to opt against central heating and to retain their coal ovens, for example, to keep costs down. Stephen Castles et al. discuss “the old assertion that the ‘German Federal Republic is not a country of immigration’ ” and remark that some have suggested ameliorative steps such as granting residence and work permits, monitoring the school attendance of the migrants’ children, and requiring “adequate” dwelling space (Castles et al. 1984: 79).

5. In the years since unification, Kreuzberg has undergone further gentrification, and now areas of eastern Berlin have emerged as centers of countercultural bohemian and artistic life, assuming the role once played by Kreuzberg.

6. Not all European host countries follow Germany’s example. The Netherlands, for instance, refuses to admit Turkish textbooks and teachers into its school system in favor of its own texts taught by resident Turks. The Dutch claim that the official books and teachers export objectionable political propaganda. West Berlin also commissioned a controversial new set of Turkish textbooks for grades one through eight. They were written and illustrated by Turkish writers and artists residing in West Berlin and contain a great deal of literature and many references that were banned in Turkey.

7. Gavur (or alternatively, kâfir) is an extremely pejorative term for non-Muslims, embodying strong moral condemnation and unambiguously asserting the user’s superiority. Technically, it only refers to peoples who are not “of the book”: Jews and Christians are thus not gavur. However, in common usage, it refers to all non-Muslims, and often to Alevis, as well. Pious Muslims used—and use—this word for Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the architect of Turkish secularism.

8. Non-Muslim minorities live in Turkey as well. There are, for example, ancient communities of Christians—Armenian, Greek Orthodox, Levantine Catholic and Protestant, and Assyrian. A Sephardic Jewish community, with roots in fifteenth-century Spain, lives primarily in Istanbul. In the far east of the country, there are small groups of Kurdish-speaking Yezidis, as well as Shafi Muslims.

9. In the late 1980s, cable had begun to arrive in Berlin, and with it a Turkish station. It is likely that this will have an affect on how much video will be viewed in the future.

10. Lemon cologne is regularly used in the context of hospitality and more generally when one comes in from outside. A generous amount is squirted into the cupped palms, then rubbed on the hands and face. It is also used in homes and commonly on intercity buses in Turkey, squirted by a young boy hired to assist the bus driver.

11. Haydar’s and most Alevi families in Berlin are from eastern Turkey. Many of these Alevis speak a Kurdish language called Zaza (others speak Kurmanci). Alevis from western Anatolia for the most part speak only Turkish and claim only the slightest affiliation with the Kurdish Alevis.

12. Although illegal, cems have always taken place in Turkey. Moreover, an Alevi revival has been gaining momentum in recent years. On the national level, Alevi assertiveness can be seen in the massive attendance at events such as the August Haci Bektash festival; a celebration of Pir Sultan Abdal that ended in tragedy, with an arson attack that killed many celebrants; and, finally, several days of rioting in Istanbul in March 1995, provoked by an attack on Alevis.

13. For the Sunnis, the phrase “to put out the candle”—mum söndürmek—is an expression that directly refers to this ritual. It is a far from neutral expression and has long gained notorious popular colloquial currency in Turkey, implying the common Sunni belief in the moral inferiority of the Alevi community. Specifically, it is a metaphor referring to the Alevis’ allegedly engaging in scandalous, immoral activities. The Sunnis would have the Alevis committing ritualized incestuous orgies when “the candles go out” at the cem. This is consistent with Sunni logic, which finds joint participation of women and men in cems offensive and sinful.

14. In view of the liberalization in Turkey vis-à-vis the Alevi population in recent years, cems are again taking place.

15. Some Alevis, cynical about “reactionary, feudal-like” abuses of power alleged against some religious leaders, scorn the dedes and cems.

Works Cited

Berlin Senat. 1994. Bericht zur Integrations- und Ausländerpolitik. Berlin: Ausländerbeauftragter des Senats.

Castles, Stephen, Heather Booth, and Tina Wallace. 1984. Here for Good: Western Europe’s New. Ethnic Minorities. London: Pluto Press.

Mandel, Ruth. 1988. “We Called for Manpower but People Came Instead: The ‘Foreigner Problem’ and Turkish Guestworkers in West Germany.” Ph.D thesis, University of Chicago, Department of Anthropology.

——————. 1989. “Turkish Headscarves and the ‘Foreigner Problem’: Constructing Difference through Emblems of Identity.” New German Critique 46 (Winter): 27–46.

——————. 1989. “Shifting Centres and Emergent Identities: Turkey and Germany in the Lives of Turkish Gastarbeiter.” In Muslim Travellers: Pilgrimage, Migration, and the Religious Imagination, ed. D. Eickelman and J. Piscatori, pp. 153–71. London: Routledge.

West Berlin Municipal Government. 1986. Miteinander leben: Bilanz und Perspektiven. Der Senator für Gesundheit, Soziales und Familie Ausländerbeauftragter, Berlin; and Statistische Berichte, Berliner Statistik, Melderechtlich registrierte Einwohner in Berlin (West), December 31.