4. “Refuge” and “Prison”

Islam, Ethnicity, and the Adaptation of Space in Workers’ Housing in France

Moustapha Diop

Laurence Michalak

In the intense public debate about migration issues in France, there has been a general tendency to treat the religious affiliation of labor migrants from predominantly Muslim countries as their most salient feature. Migrants in France are, indeed, almost all Muslim—Arab North Africans, West Africans, and Turks. Yet we should not assume that religious affiliation necessarily plays a preeminent role in the position of labor migrants vis-à-vis the host country. For example, almost all Latin American migrants to the United States in recent years have been Christian, but religion plays no role in American discourse on migration. In France, however, where most migrants are of a different religion than their hosts, “Muslim” has become a synonym for “other”—or, some would argue, code for “nonwhite.” If migrants increasingly speak as “Muslim,” finding such an identity natural and effective in the new contexts where they live, we must see that in part as a label thrust upon them.

Muslims in France do not act to any significant degree—or at least not yet—as a corporate group, with a consciousness of unity, a sentiment of solidarity, and a consensus for collective action. Islam appears to be increasingly an aspect of “ethnicization,” which may or may not transcend national and other social divisions. The importance of domestic settings for constructing such social identities is evident throughout this volume. One of those settings is the densely populated, highly charged, semipublic space of the foyers created in France for migrant workers, whose space has sometimes, in important ways, been made Islamic.

| • | • | • |

The Foyers in France

The foyer is a ubiquitous aspect of the French urban and architectural landscape wherever there are high concentrations of foreign workers. The term foyer, or “home,” with its domestic connotations, is ironic, in that the foyers rarely house families and typically forbid couples and children. The migrants in the foyer are frequently married, but they have left their families in their countries of origin. The foyer is a social universe of non-French males, an island of workers, usually unskilled or low-skilled, away from their homelands and isolated from their families. In fact, foreign workers have had high rates of unemployment in recent years, so that the foyer has become a kind of reservoir of cheap foreign labor.

The function of the foyer is to provide sleeping accommodations and common facilities for its inhabitants. Several workers may share a room or a group of small individual bedrooms, grouped around a shared kitchen/dining facility and a bathroom.

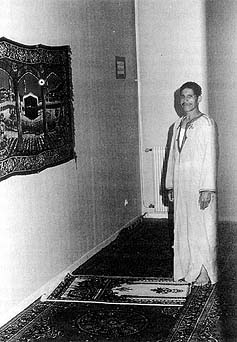

A single building or group of buildings with multiple clusters like this forms the foyer. The foyer may also have common rooms, such as a room for Muslims to perform their daily prayers, like the makeshift room shown in figure 15. The foyer tends to be isolated—located away from the urban center, contiguous to places such as cemeteries and garbage dumps, typically found at urban peripheries. To compare the foyers to concentration camps or minimum security prisons or urban reservations would be too harsh. To compare them with youth hostels and student residences seems too mild.

Figure 15. A makeshift room for prayer in a foyer in the Var region of southeastern France. Note the rugs and the hanging with the Ka‘ba image to indicate the direction of prayer. Photograph by Laurence Michalak.

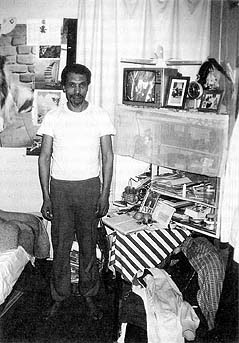

The first modern foyers for migrant workers in France date from the early 1950s, but their rapid spread began when the French government passed a law (Article 116 of Law No. 56–780 of August 4, 1956), creating SONACOTRAL, the Societé nationale de construction de logements pour les travailleurs algériens (National Company for the Construction of Housing for Algerian Workers), to finance, construct, and manage housing for “Muslim French from Algeria come to work in metropolitan [France], and for their families.” SONACOTRAL was clearly expected to help keep closer control over Algerian workers in France, but algérien was dropped from the name in 1963, and the organization is now called SONACOTRA. By the early 1980s, other organizations—such as the ADEF (for management of construction-workers’ foyers), AFTAM (which included students and had a mainly sub-Saharan clientèle), and AFRP (for North Africans in the Paris region)—together accounted for another 128 foyers with 35,338 beds (Ginesy-Galano 1984: 28–48). By the end of 1988, SONACOTRA controlled 69,000 rooms and 1,800 apartments in 330 establishments, with a staff of 1,100 (Gagneux 1989). SONACOTRA today justly describes itself as “France’s Number One Host”—it is the largest entity in France in the field of hotels and housing. Figure 16 shows a small room in a SONACOTRA foyer. The next largest foyer organization is an umbrella group of organizations called UNAFO, the Union nationale des Associations gestionnaires des foyers des travailleurs migrants (National Union of Associations Managing Foyers for Migrant Workers), which includes most of the smaller foyer chains, totaling nearly 50 associations with about 260 foyers, 52,000 beds, and 2,200 staff, housing a mobile population (Brun-Melin 1989).

Figure 16. A Tunisian worker in a room in a SONACOTRA foyer. Photograph by Laurence Michalak.

| • | • | • |

West Africans in the Foyers

The modern history of black African immigration to France began after World War I, when former African soldiers (known as tirailleurs sénégalais, or Senegalese infantrymen) were allowed to work on merchant ships as kitchen hands, coal trimmers, and stokers. In 1945, West Africans were employed as seamen in the context of government concerns about shortages of labor. After World War II, however, French seamen urged that French be hired ahead of foreigners—notwithstanding that many West Africans were French citizens. Between 1954 and 1959, the immigration of seamen, along with many unskilled and low-skilled workers, continued.

After 1960, African immigration to France increased with colonial independence. A multilateral agreement between France and the African states allowed members of the Franco-African Commonwealth to move without restriction to France or to the other African states that had formerly been components of the French empire (namely, Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal). African migration to France during the 1960s was usually temporary, lasting about four years. But after 1974—the official date suspending immigration into France—black Africans began to settle in for good.

There are officially 172,689 Africans in France from eighteen nations, making up 4.5 percent of the foreign population, according to the 1982 national census. The largest African group are from Senegal (33,242 people), followed by migrants from Mali (24,340), Cameroun (14,220), Ivory Coast (11,680), and Mauritania (5,060). West Africans work in industry (38 percent), in services (32 percent), in building and civil engineering (8 percent), in domestic services, and in the textile and confectionary industries.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, West Africans were housed in slums, including old factories adapted for housing, in cities such as Marseilles, Rouen, Le Havre, Paris, and Montreuil. In Paris, they were mainly concentrated in the eleventh, twelfth, eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth arrondissements. In 1962–64, under a 1901 law, associations were created for the purpose of lodging black Africans: Accueil et promotion (Welcome and Support); ASSOTRAF, the Association d’aide sociale aux travailleurs africains en France (Association for Social Aid to African Workers in France); and SOUNIATA, the Association pour le soutien, la dignité et l’unité dans l’accueil aux travailleurs africains (Association for Support, Dignity, and Unity in the Welcome of African Workers). These associations were directly or indirectly created by the government and were run by French political figures who claimed that they were “friends of Africa,” some of them with links to former French colonies. Thus, in the late 1960s and the 1970s, while SONACOTRA took care of the Maghrebis and European migrants such as Portuguese and Yugoslavs, these other associations looked after the West Africans. SONACOTRA began giving rooms to black Africans in the mid 1970s, when it was ordered to do so by the prefecture of Paris. In the Ile-de-France, a quarter of UNAFO’s 126 foyers serve mixed populations, while only 11 of SONACOTRA foyers do.

West African foyers usually house people either from the same region or of the same ethnic origin, or at most perhaps two or three different ethnic groups or nationalities. All or nearly all of the people in these foyers are Muslims. Two main groups are usually to be found in the foyers—the Soninke, or Sarakolle, and the Tukuleur (from the Senegal River Valley, shared by the three countries of Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal). In Paris, the foyers are mostly Malian, while in Les Mureaux and Mantes-La-Jolie (Yvelines), the Senegalese are the majority. There are other ethnic minorities in the foyers as well, such as the Bambara (Mali and Senegal), the Manding (Senegal and Mali), and the Manjak (who are Catholic and come from Senegal and Guinea-Bissau).

The social life of the residents replicates significant features of life in their homelands. All the ethnic groups—except for the Manjak—have strong hierarchical organizations, and despite the overcrowding, divisions between nobles and commoners are respected through invisible barriers. Every man has his place. The head of the community, or the village, is always a man of high birth. Among the Soninke, the head is helped in his task by a council of nobles, who see to the administration of the community or village. The council looks after the morality of the group, monthly dues for food, and the lodging of newcomers or people in need (because of illness or unemployment). It also provides help for the village of origin with mosques, schools, sanitary arrangements, and so on.

Just below, or sometimes at the same level as, the notables stands the marabout. He is very important in the group, serving simultaneously as secretary, confidant, teacher, leader, and talisman-maker, and is usually well trained in qur’anic and Islamic studies. The marabout is also expected to moderate the tendency of the griot—a kind of troubadour and historian—to rekindle ancient quarrels between noble families. The griot is Janus-faced. According to the circumstances, he can act on the “pagan” side of the nobles, rekindling memories of the glorious past of the Soninke people, or he can put on Islamic dress and go hand in hand with the marabout. At the bottom of the social pyramid are the lower categories of traditional craftsmen (cobblers, smiths) and the “slaves”—the descendants of former prisoners of war.

There is a complicity between the noble, the marabout, and the griot—a web of collusion so well spun that the lower-status groups assent to their conditions without making too much fuss, even when and if they are more educated and more knowledgeable about French society than their “masters.” In the Soninke communities, the cooking must always be done by the “slaves.” In return, the “masters” must be lavish toward them, especially during traditional feasts such as those at initiations. On these occasions, the dividing up of space in the meeting rooms reveals the underlying principles of exclusion and inclusion. Women sit apart from men, and Islamic rather than traditional practices are invoked. There is a subtle spatial segregation between nobles and commoners. As for the lower social categories, they are busy helping the nobles and their guests. The boundaries are subtle. Everyone knows where and next to whom to sit.

Residents of the foyers are outspoken and articulate in describing the negative aspects of their lodgings. They perceive their lodgings as “prisons” or “concentration camps,” and individual rooms as “tombs.” Still, despite these criticisms, most West African residents also acknowledge positive aspects of the foyer: “The foyer is my second village”; “It is a place where things go well”; “It is very secure, a welcoming place compared to the aggressiveness of the town”; “In the foyer, people come and go without problems.”

Were the foyers created in order to further the segregation of migrant workers? Whatever the answer, one must acknowledge that foreign residents have transformed the space of the foyers, using it to their liking. In place of the official rules of the foyer, they have substituted unofficial rules of their own.

In the 1970s, the foyers, whether Maghrebi or West African, were strictly supervised by directors who were, for the most part, French army veterans who had served in Indochina, Algeria, or West Africa. Administrative rules were drastic. Visits from people outside the foyer were severely controlled, largely limited to male relatives, at fixed hours and in the television room only. After 8:00 p.m., the director could enter and inspect any room. The director would play off one nationality against another, first of all by separating nationalities into specific floors, and secondly, by emphasizing the cultural or religious differences between nationalities or ethnic groups. This period of military-style rule came to an end after the widespread 1975 strike about living conditions in the foyers. From that time on, the African foyers were open to free visitations and susceptible to “stowaways”—illegal residents from outside.

Nowadays in an individual room there may be the “official” bed, plus two or three folding beds, like the rooms of Mourides or Turks (see Ebin, Mandel, this volume). During weekends, the rooms are filled with visitors in traditional dress, sitting wherever a place can be found, chanting in loud voices, and drinking tea—which is perceived as an Islamic beverage. Meals of meat, or fish, and rice are also served, whereas during the period of military directors, it was forbidden to eat in the rooms. In some rooms of Muslim residents, one can see, among other decorations, a Hegira calendar, pictures of Mecca, ornate qur’anic calligraphy, and perhaps photographs on a table of a spiritual leader or a new mosque in an African village of origin. In the rooms of marabouts or educated Muslims, there are Islamic and Arabic books and a prayer rug in a corner. Thus sanctified, the place can become a site for prayer or religious education, so that space is defined by practice, not convention, much as it is described in several chapters of this book.

In the quest for identity, black Africans have endeavored to appropriate different collective areas of the foyers, including the corridors, the communal dining rooms, and the courtyards. The foyer has become multifunctional—a place of business and a place of worship. In nearly every African foyer, there are traditional activities such as craftsmen’s workshops, markets, and restaurants. The latter are run by women, Malians for the most part, who are helped by “slaves,” and sometimes by unemployed young commoners. The food usually consists of rice, meat stews, and sometimes chicken and chips (called a “European meal”). The price varies between eight and ten francs. The midday meal draws customers from outside, both migrants and French workers, into the foyers.

In most of the foyers, the common rooms and the corridors also serve as marketplaces. The market is usually conducted by men of high rank from the community, and their rooms become warehouses. The market provides different types of products—cigarettes, soap, chewing gum, sweets, African toothpicks, kola nuts. At weekends, the market increases in size, and, in some foyers, it is “sanctified” by such products as religious tapes, prayer rugs, Islamic calendars, religious books for different reading levels, prayer beads, incense, “Indian” perfumes, and even “halal” meat. The markets that specialize in these products are situated in foyers in which the “mosques” and village association meetings draw from five to eight hundred people on weekends.

In summertime, the courtyards of the foyers are taken over by men selling both raw and roasted ears of corn. An ambience conducive to informal socializing is created. The smell of roasted corn fills the air, and people stay up late. These marketplaces become places for meeting, discussion, and the construction and the consolidation of different kinds of identity.

In the 1970s, the landlords began to tolerate workshops in the foyers, so that black Africans could make a living related to their “tradition and culture.” Tailors, cobblers, and smiths carry on their professions in tiny shops—perhaps fifteen square meters for five or six craftsmen. Some of these people work only on weekends; others work every day and even at night—especially tailors at the approach of Islamic festivals.

During the Islamic holiday of the ‘Id (French: Ayd), people of lower status, especially cobblers, become butchers. The slaughtering of sheep in black African foyers began in 1971, after a social commission associated with the sixth national plan advocated support for cultural activities in the foyers. With the money that was allocated for this purpose, black Africans working through the foyers bought sheep for sacrifice at the Islamic new year and during the ‘Ids, and invited lodgers, policemen, and mayors’ delegations for these occasions.

In the France of the 1990s, however, ritual slaughtering has become a big issue, giving non-Muslims presumed moral ground to challenge the Muslim presence. This recalls “moral” causes discussed elsewhere in this volume in relation to Muslims: architectural conservation (Eade), “noise pollution” (Eade), and women’s rights (Bloul). Petitions have been drawn up by humane societies, the National Front, and the French butchers’ lobby to protest this practice. In January 1990, the famous movie star Brigitte Bardot vigorously attacked religious animal slaughter, both Jewish and Muslim, in an interview on French national television. She repeated these attacks in August in Présent (August 1, 1990), a newspaper sympathetic to the National Front, France’s extreme right-wing party. But this time she objected, not only to the Muslim method of animal slaughter, but also to the French government policy, which “tolerates such ritual sacrifices and allows the spread of Islam in France. It’s a shame.” In the meantime, the Conseil de réflexion sur l’Islam en France, composed of Muslims of different nationalities and created in 1990 by the ministries of Interior and Culture, is trying to find ways to resolve this issue.

The foyer is also a place of worship. The first prayer room to be instituted in a black African residence appeared in 1967, located on the ground floor of the foyer “La Commanderie” in the nineteenth arrondissement of Paris. The next year a marabout living in the same building transformed his own sixth-floor room into a prayer room. He argued that a “mosque” should not be something given by non-Muslims; Muslims should themselves open their own prayer room. The marabout, who has now returned to Africa, thus drew a distinction between legitimate and illegitimate prayer places.

Only in 1977 did a second foyer introduce a prayer room. Despite this slow beginning, now almost all foyers have prayer rooms, which are subsidized by all residents of the foyer, whether Muslim or not. UNAFO, the principal organization of black African foyers, has, for example, 126 foyers in the Ile-de-France, of which 119 have prayer rooms.

The prayer rooms may be located on any floor—basement, ground floor, or various upper floors. The sizes vary, averaging around thirty to forty square meters. The prayer room is usually well furnished with multicolored carpets and contrasts with the rest of the building in its tidiness. A box for donations is always hung inside the room, next to the exit.

On weekdays, the prayer room may not be more than 20 to 30 percent filled. But on Fridays and during the ‘Ids, it is completely full and people—both residents and outsiders—overflow into the courtyard. On such occasions, the nearby pavements become part of the prayer place, bewildering French neighbors, who talk about being “invaded,” a telling metaphor. Two other dates offer opportunities for gatherings. The first is the Night of Destiny, the 26th to the 27th of the lunar month of Ramadan, when people assemble all night for prayer and recitation of the Qur’an, and food is brought in by the families of the residents and by outsiders. The second opportunity is Mawlud—the Prophet’s birthday.

In some foyers, the prayer rooms are used as classrooms, albeit without tables or chairs. Qur’an and Arabic classes are conducted for children, with the lowest-level group next to the teacher and more advanced groups and individuals scattered about in different corners of the room. For the adults, lectures and talks follow the weekend afternoon prayer (salat al asr).

The “mosque” in the foyer contributes to the formation of Muslim identity. Even nonpracticing Muslims seem proud of its existence. The territory of the “mosque” is perceived, in principle, as a base that belongs to all Muslims, and, as such, it is a symbolic place of safety.

| • | • | • |

North African Arabs in the Foyers

The collective life in the foyer of labor migrants faced with poverty and isolated from country and family would seem to offer the potential of comradeship, even of political action. The very fact of residence in a foyer has been important on occasion, as when foyer residents organized rent strikes in the 1970s. As the strikes led to improvements in conditions in the foyers, especially the relaxation of visiting rules noted above, tenants’ organizations appeared to lose their raison d’être. Nor have the Tunisian, Algerian, and Moroccan amicales, or “friendship organizations,” been very effective. All tend to be small groups dedicated to performing useful services, such as repatriating dead bodies. North Africans certainly tend to identify with their countries of origin, but this is not manifested through adherence to voluntary organizations such as the amicales, and their national sentiments are more cultural than political.

Islamic practices, often centered on the foyer, are typically part of those cultural sentiments. A 1985 survey conducted by Michalak in the Marseilles area included questions such as:

Of being Muslim, Arab, and [Moroccan/Algerian/Tunisian], which is most important for you?

How do you spend Ramadan in France?

Do you fast when you work?

Do you believe in God? Pray? Give alms?

Have you made or do you plan to make the hajj?

Do you drink alcohol? Eat non-halal meat?

Are you a good Muslim?

Have you changed your practice in France?

Is there a place to pray where you work?

Have you given money for a mosque?

Are you a member of an Islamic organization?

What is your opinion about Islamic political groups?

To the question of primary identity, all but one of those interviewed replied that their main identity was as Muslims. “There is no God but God,” one worker said; “that comes before anything else.” Some denied having any identity besides being Muslim; “My only nationality is God,” said one. National identity usually came next, then regional identity. Everyone interviewed affirmed belief in God and in Muhammad as His Prophet.

All those interviewed, both formally and informally, claimed to fast during Ramadan, even those who did heavy manual labor on farms. As one person described it:

Another said:During Ramadan it’s hard and tiring, especially when Ramadan comes in the summer with long days and heat. I come home and fix dinner, eat at 9:00 or 10:00 p.m.—I fast longer than sunset because I have to cook. Then I go to the mosque [prayer room in the foyer] until 1:00 a.m. for the prayer—yes, for about 2 ½ hours. Then I come back to my room and sleep and get up at 2:00 a.m., eat, and go to work. I hardly sleep during Ramadan.

Far fewer people pray than fast. About half of those interviewed performed the daily prayers—usually cumulatively, rather than at the five prescribed intervals, in order to avoid interrupting their work. Nobody interviewed had a workplace with a prayer room.I work better when I fast, especially after the second or third day. I fast, I pray in the evening, I read the Qur’an, and I work. My children fast too.

The foyers are sometimes focal points because of their prayer rooms. A typical prayer room in a foyer has minimal furnishings, such as a rack for shoes; rugs, which are rolled up and placed on shelves when they are not in use; a set of five cardboard clocks with movable hands posted on the wall to indicate the five times of prayer; and a small carpet with the image of the Ka‘ba mounted on the wall to indicate the direction of prayer (fig. 17 below). Some prayer rooms in the foyers used to be canteens, which, among other things, served alcoholic beverages, but were converted to prayer rooms at the request of the residents. This is an example of the adaptation of French space by Muslims.

On Fridays, an imam usually leads the prayer in the foyer prayer room and gives the Friday sermon. One respondent described the imam in his foyer as follows:

The prayer rooms at the foyers are usually open to anyone, from within or outside the foyer, and outsiders do come in to pray, especially on Fridays and especially in places with no mosque. Of course, many pray privately. One agricultural worker said that he worked every day except Sunday and prayed in the fields. So attendance at the Friday prayer is not a reflection of the numbers of Muslims who actually pray.Our imam is sixty-three years old and is Algerian. On Fridays he gives a khutba—about Muslim life, the life of the Prophet, the words of God, what things are halal and haram. The imam was a worker, and we pay him with donations. People who earn good wages and don’t have large family responsibilities give 50 or 100 francs a month each. One of the foyer residents replaces the imam for the Friday sermon when he is on vacation. On weekdays, anyone among those present, usually someone older, can lead the prayer.

One of the foyer residents told me that he sometimes prayed at his workplace in a relatively unfrequented room where broken equipment was stored:

The factory supervisors may have been avoiding potential controversy. The worker, however, believed that because he was engaged in prayer, he was rendered invisible and under divine protection from any harm.One day about two years ago—I’ve been working there for eight years now—I put down my cardboard in the tower in front of the door and was praying. Then my foreman came in. He was with a big boss of the company visiting from Paris, and the director of the refinery and a bunch of engineers—a whole crowd. I said to myself, he’s going to say I’m stealing time from my job, and fire me. Well, I continued my prayer, and they visited the room as if I wasn’t there, and left. Later I saw the superintendent and asked him about it, but he didn’t know what I was talking about. He said yes, he had taken the group on a tour, but he hadn’t seen me. I asked one of the other people who was in the group, and he hadn’t seen me either.

The North Africans generally agree that it would be a good idea for there to be a real mosque to pray in—not just a room set aside for prayer in a secular building. As one worker said:

No worker in the sample had yet been on the pilgrimage to Mecca, although they all said they would like to go some day.I read in the newspaper the other day that there are 450 mosques in France and 33 in Bouches-du-Rhône. We Muslims should take care of building the mosques, and the consulates and the North African governments can help us. You have to get an authorization from the city hall to build one. I’ve given money for mosques. [Here] we need to get a bigger place to pray, to be on our own. There’s a really good, big mosque in Marseilles, near the old city gate.

North African workers often try to time their vacations so that they can participate in zardas, the annual festivals at rural North African shrines. One worker said:

Another worker expressed an objection to zardas, reflecting the opinion of reformers and some transnational Islamic movements:The zarda of Sidi Tahar, who was a son of Sidi Abdelkader, is always in the late summer, after the harvest, starting on a Wednesday afternoon and lasting until Thursday morning, with a hathra (ecstatic dance) and a draouch (divination), but which week the zarda will be is always set at the last minute. Nobody ever has to tell me when it will be. I just wake up in the morning and I know. I go to work and tell the boss, I have to go, and he says, go. I’ve never been refused.

The zarda is an error, a false Islam. You can’t ask a marabout like Sidi Belkacem for help. He wasn’t a prophet. Muhammad was the last prophet. You can’t ask Muhammad for help either. You have to ask God.

It is possible that the status of being a member of a Muslim minority in France tends to make some workers more Muslim than if they had stayed at home. That is, people become ascriptively Muslim when they are born into Islamic settings, where minimal religious practice—for example, fasting—is expected. In a non-Muslim setting, practice of Islam may become more self-conscious and linked to expressing a group identity.

In a situation of being part of a Muslim minority and encountering hardship and adversity, some migrants may become more observant Muslims, or join Islamic groups that can organize with greater freedom abroad than at home. The phenomenon of being treated as a Muslim by non-Muslims also reinforces Islamic identity. None of the workers I interviewed, however, expressed enthusiasm for Islamic political movements, for which they often use the pejorative term khawangiyya (from the ikhwan, the Muslim Brotherhood). One worker associated Islamic political movements with sabotage. Another, evincing absorption of French values (cf. Bloul, this volume), remarked, “Politics and religion should not mix; you can talk about politics in the amicale, but not in the [prayer room].” Several spoke of increased practice:

One might argue that many people have become more observant in Islamic countries too, especially in these times when Islamic practice is being intensified. In this instance and in many other instances, however, the return to Islamic practice was brought on by an experience of discrimination abroad, which makes migration an important element in individual religious experience.I prayed from when I was about seven because my father made me, and in school, and then for a while after I finished school, until I was eighteen. When I came to France that changed. I found another system of life. From 1971 to 1978, I worked in a factory in the Alps where they made jam and tomato paste and other preserves. In 1978, they wanted me to work in the kitchen and make preserves from pork. I explained that I couldn’t. They said they would fire me if I didn’t, but I wouldn’t set foot in that kitchen. Then I came here, where I had friends. I found work after only two days. Ever since then, I pray every day.

There is a political advantage to emphasizing Muslim identity in France. In separating church and state, France guarantees religious freedom. Since Catholics and Jews have the right to build churches and synagogues, for example, Muslims logically have the right to build mosques. There has been discussion in France of creating a commission for Islamic representation. Thus workers might adopt an Islamic stance, not only out of conviction, but also as a strategy for dealing with the French authorities under certain circumstances.

| • | • | • |

Ethnicity in the Foyer: Interaction Between West Africans and Arabs

In mixed settings, generally speaking, Maghrebis and black Africans do not emphasize their ethnic or national identities. Still, the foyer bears in itself the seeds of potential conflict. An illustration of this is a survey carried out in fifteen foyers in the Lyons region in 1978, since which time things have changed very little. The survey noted that quarrels frequently occurred over the use of kitchens. Muslims complained that European residents cooked pork on nearby stoves, which tainted their meals. Disputes between Muslims and Christians, between Turks and Maghrebis, and between Algerians and Moroccans arose for any number of reasons.

A serious example of strained relations between black Africans and Maghrebis took place in 1975 in a foyer in Villejuif (a suburban town near Paris), when a small incident developed into a major riot. A Maghrebi poured water down on some black Africans who were speaking loudly under his window. This escalated into a violent interethnic conflict, which lasted for three days, despite the intervention of the French Special Police (the CRS). There were six deaths in all—three on each side.

A basic source of contention is the difference in community life and the use of space in the foyers. The Maghrebis, in part because they have been in France longer, have become more individualistic. The black Africans have not only come more recently, but, as villagers, resist passage from wider spaces to the tiny and orderly spaces of the foyer. As a result, black Africans are seen as encroaching upon the territory of others.

Black Africans seek to increase their numbers. When a room becomes vacant, they press for it to be rented to someone from their community. In some of the foyers in Seine-Saint-Denis, this policy has worked so well that the Maghrebis have left one by one. Maghrebis tend to cook and eat individually, while for the black Africans a meal is a major social occasion for the exchange of news, jokes, and laughter. The black Africans thus gradually appropriate the whole collective space as their exclusive domain.

Faced with this situation, the Maghrebis may simply leave for private lodgings in towns; others stay, but withdraw into their rooms, which they furnish with television sets, telephones, and drinks (as in Val-de-Marne, for example). The majority of North Africans try to lodge with other North Africans through lobbying the residents’ committees.

Some, however, confront the black Africans on religious grounds. They equate true Islam with Arabs only, and stigmatize the religious practices of black Africans. As Arabs, they look down upon black Africans as people who belong to Sufi turuq and are ignorant of the Arabic language, and therefore of the Qur’an. They try to assume the lead in the collective prayer in the prayer room and to exclude black Africans from directing prayers.

Foyer managers tried to use this division to break the strikes of the 1970s. Many foyer managers brought numerous black Africans into the SONACOTRA foyers, hoping to divert discontent into intercommunity conflicts. In fact, the two groups combined against SONACOTRA. Both French trade unions and the Algerian amicale tardily tried in vain to take over the strikes. The government’s actions, including deportations, only hardened the resolve of the strikers. In the end, the strikes not only led to some improvement in living conditions, they gave the workers the opportunity to establish their own residents’ committees, control the use of the foyers, and play a role in forging new identities.

One aftermath of the 1970s strikes has been the assertion of an Islamic identity. At that time, calls for the creation of more prayer rooms became more insistent. Requests for facilities for Islamic practice are clearly older than the Khomeini era. The “foyer mosques” are a mark of Islamic identity for all Muslims, be they regular or irregular in their attendance at prayers. From the late 1970s to the early 1980s, Maghrebis were reluctant to pray under a black African imam. Yet even then, the significant distinction began to be that between regular and irregular mosque attenders.

To claim to be a Muslim by birth was no longer sufficient. There appeared a coalition of observant Muslims, both black and Arab—who organized their lives apart from the others, offering an alternative to the traditional organization described above. They offered one another mutual support, especially in relation to the pilgrimage. On occasions such as Ramadan, and especially the Night of Destiny, they regularly assembled in the “mosque” for qur’anic recitation and prayer.

The brothers in the faith began campaigns to purify the “pagan” parts of the foyers. Beer was no longer to be served in the foyers, and prostitutes were forbidden entry to them. “Cleanliness is next to godliness” became the rule. The regular attenders began their dawa (“mission”) among the infrequent attenders, who were invited to attend religious lectures. Celebrations of Islamic festivals became more elaborate. There were frequent discussions of the importance of true jihad during Ramadan. Clocks were displayed to show times of prayer (fig. 17).

Figure 17. Clocks set to show prayer times as part of an effort within the foyer to encourage Islamic practice. Photograph by Laurence Michalak.

Those who kept on living as usual—especially younger Maghrebis and black Africans—were marginalized as black sheep. Differences also emerged among the regular mosque attenders, again a cleavage not following lines of nationality. The believers in turuq opposed the people of the hadith. The Soninke belong for the most part to the Jama‘at Tabligh (see Metcalf, this volume). The Soninke stigmatize the Tukuleur (who are faithful to the Tijaniyya tariqa) and tend to associate instead with the Tabligh Maghrebis. In some foyers in Les Mureaux (Yvelines), the prayer rooms are divided in two after the main prayer of the day. On one side the turuq believers gather in a circle, performing their wird (special recitation of a tariqa). On the other side, the Tabligh assemble under the direction of their amir to introduce newcomers to the finer points of the true religion. The rivalry between religious groups gets more acute during Ramadan and on the eve of the hajj. Every group tries to draw in more people to attend lectures. This rivalry divides Maghrebis and black Africans among themselves.

| • | • | • |

Conclusion

The foyers, which were built to provide sleeping quarters for transitory men, have been transformed into multifunctional institutions for long-term and permanent residents. The different functions of foyer space accord with different aspects of migrants’ identities. Thus the foyer residents engage in social interaction as Soninke or Tatouin in one context, Tunisian or Malian in another, sometimes as consumers, sometimes as Muslims.

In examining the foyers, we have called attention to the significant ways in which black West Africans and North African Arabs act to appropriate and transform foyer space. However, these foyer residents operate within contexts of considerable constraint. They cannot truly “appropriate” space in the foyer setting, and they can “transform” it to only a very limited extent. The foyer buildings are not “theirs” in any sense of ownership. Architecturally, the foyers are buildings conceived by non-Muslims for ends that have nothing to do with community, religious or otherwise. On the contrary, the foyer both isolates individuals (as in the small suites of the SONACOTRA model) or concentrates them in stifling density (as in the case of the West African foyers in the Ile de France and in some of the non-SONACOTRA foyers). To the extent that foreign workers succeed in adapting this foreign space, they work against the grain, making superficial modifications, within local and national political climates that are at best neutral and at worst explicitly hostile. Islamic practices such as prayer, ‘Id, and wird have been one way in which workers have defined themselves as best they could and made this space their own. The capacity of the workers to create meaningful relations and ritual is the more dramatic in such harsh settings.

Works Cited

This essay is based on the research of Moustapha Diop on the predominantly black West African foyers of the Ile-de-France and of Laurence Michalak on the predominantly Arab North African foyers of the Bouches-du-Rhône.

Barou, J. 1978. “Les Causes de sous-location dans les foyers SONACOTRA de la région lyonnaise.” Report. Paris: SONACOTRA.

Brun-Melin, Annick. 1989. Les Foyers vus par les professionels. Brochure. Paris: Union nationale des Associations gestionnaires des foyers de travailleurs migrants (UNAFO). June.

Diop, Moustapha. 1988. “Stéréotypes et stratégies dans la communauté musulmane de France.” In Les Musulmans dans la société française, ed. R. Leveau and G. Kepel, pp. 77–87. Paris: Presses nationales des sciences politiques, Fondation nationale de science politique.

——————. 1989. “Immigration et religion: Les Musulmans negro-africains en France.” Migrations-Société 1: 45–57.

d’Orso, Louis (president). 1980. L’Association des Foyers de Provence et de Corse à 30 ans: 1950–1980. Brochure. Paris: AFPC.

Gagneux, Michel (president). N.d. [ca. 1989]. SONACOTRA: L’Habitat en mouvement. Brochure. Paris: SONACOTRA.

Ginesy-Galano, Mireille. 1984. Les Immigrés hors la cité: Le Système d’encadrement dans les foyers (1973–1982). Paris: L’Harmattan / CIEM.

Labbez, Joelle. 1989. Les Soviets des foyers. Paris: Editions Albatros.

Leveau, Rémy, and Gilles Kepel. 1985. Culture islamique et attitudes politiques dans la population musulmane en France: Enquête éffectuée pendant le mois de Ramadan (mai–juin) 1985. Paris: Fondation nationale des sciences politiques.