11. The Muslim World Day Parade and “Storefront” Mosques of New York City

Susan Slyomovics

The Muslim World Day Parade and the “storefront” mosque both present images of Islam in the city of New York, illuminating political and organizational activities that promote symbolic modes of expression for an emerging Muslim community.

New York City dwellers are nationally famous for their use of collective gatherings such as public parades to enact complex social relations of ethnicity, religion, and power (Kasinitz and Friedenberg-Herbstein 1987; Kelton 1985; Kugelmass 1991). One day each year since 1986, city streets and urban neighborhoods have temporarily reflected festive images of Muslim community solidarity. Similarly, numerous “storefront” mosques (parallel to “storefront” churches and temples) constitute a specifically Muslim reusage and makeover of the quintessential urban venue, the commercial storefront: a first-floor space facing on the street, its entrance flanked by glass windows for merchandise display, that is generally owned or rented by a business for use as a shop. In the terminology of vernacular architecture, the term storefront is extended to housing stock, such as apartments, suburban homes, or lofts, when it is transformed into markedly different spaces and new uses—in this case, to sacred space functioning as a mosque.

The storefront mosque comes under the rubric of “non-pedigreed architecture,” a label designating the “vernacular, anonymous, spontaneous, indigenous” constructions of the informal, undocumented sector (Rudofsky 1964). So too a parade can be considered as vernacular street drama whose social context, like the storefront mosques, mirrors the changing demographics of the city. In addition, the Muslim World Day Parade explicitly draws upon the iconography of the mosque, not only as a form of self-representation, but also as an image for non-Muslim audiences to interpret.

| • | • | • |

The Muslim World Day Parade

The oldest continuous civic parade in New York City is the Irish-American St. Patrick’s Day Parade, which celebrated its two hundredth and thirty-first year in 1993. Many of the subsequently established one hundred and sixty-eight annual ethnic day parades currently marching in downtown Manhattan borrow from the Irish prototype the established “grammar” of parade enactment: floats, marching bands, forward military-like march formation, related community groups, local politicians, banners, and so forth (Kelton 1985: 104). The recently inaugurated Muslim World Day Parade has added the performance of mosque architecture, Muslim procession, and prayer to the visual repertory of parade display.

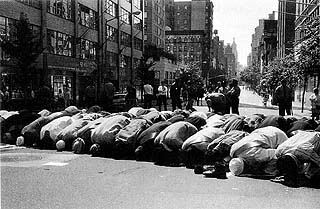

The Muslim World Day Parade begins with the marchers transforming the intersection of Lexington Avenue and Thirty-third Street into an outdoor mosque (fig. 37). The mosque is, literally, a masjid, “a place where one prostrates oneself [before God],” in the context of canonically fixed movements and verbal repetitions. Strips of plastic are laid down diagonally along Lexington Avenue so that participants and worshippers face the northeast corner of the two intersecting streets. The parade thus begins with an outdoor collective ceremony that demarcates the Muslim community and represents the primordial and recurrent moment of the sanctification of the community and the world by a prayerful gathering for which no specific architectural setting is necessary.

Figure 37. The 1991 Muslim World Day Parade: Lexington Avenue and Thirty-third Street becomes an outdoor mosque. Photograph by Susan Slyomovics.

Floats, a necessary feature of New York City parades, here take the form of scale models of the three holiest mosques of Islam, concrete expressions of the faith. Parade organizers present these mosques as cultural symbols to teach historic and religious values. First, the Ka‘ba, the holiest shrine in Islam, is identified as the “House of God, located in Makkah [Mecca], Saudi Arabia.” The second site, that of Muhammad’s heavenly ascent, is also identified by place: the Dome of the Rock, which “is” Jerusalem (al-Quds, the name of the mosque and the city). The third, the Masjid Al-Haram, is identified by its location in Medina and its role as the burial place of the Prophet. The information conveyed about these floats is presumably for non-Muslims.

Indeed, a significant characteristic of the Muslim World Day Parade that contrasts with other parades is the visual importance and legibility of banners and signs. Parading banners or carrying the word of Islam becomes the parade’s most noteworthy feature and one that points, at the same time, to the omission of other classic parade entertainments: scantily clad females, women on display in floats, dancers, and so forth. Signage identifies specific Islamic organizations and sites unknown to the spectators, who thus acquire knowledge of New York’s newer religious groupings by reading the unfolding documentation of the breadth of Islam in the world or even of its local co-ethnic permutations (e.g., the Islamic Society of Staten Island, the Chinese Muslim organization, and PIEDAD, the acronym for the emerging Hispanic Muslim community).

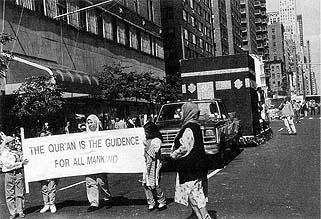

Muslim marchers also carry their message by means of banners largely in English with quotes explaining Islam and specifically targeted to non-Muslims: “the qur’an is the guidence [sic] for all mankind” (fig. 38). Bystanders literally read ambulating sacred texts as if cinematic subtitles were translating the gestures of the marchers to the viewers. Signs proclaim, “There is no God but Allah the One, the Absolute, the Almighty, One Creator, One Humanity,” followed by signs bearing the names of Jewish and Christian prophets recognized by Islam, with Muhammad as the last seal of prophecy: “Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus and Mohammed.” Many signs emphasize Islam’s inclusive embrace of figures identified with Judeo-Christian religions, all of whom are honored by Islam. Such signs are also characteristics of the Muhurram procession in Canada and the Sufi processions in Britain described elsewhere in this volume (cf. Schubel, Werbner).

Figure 38. The 1991 Muslim World Day Parade: Banners preceding the float of the Ka‘ba. Photograph by Susan Slyomovics.

The domain in which the parade takes place is a prominent New York City public space: a march southward down Lexington Avenue heading from Thirty-third Street to Twenty-third Street, a route identified with South Asian food, travel, and sari stores. Thus, Muslim space on a New York City avenue can be temporarily created by combining two contrasting forms: the ephemeral structure and format of a civic parade and the monumentality of mosques on floats during the parade (Slyomovics 1995).

| • | • | • |

“Storefront” Mosques

Muslim civic parades highlight issues relevant to a survey of some New York City storefront mosques: the use and nature of signs, the designated space in which to hear the call to prayer, the orientation toward Mecca, and the presentation of the Muslim self to the American public.

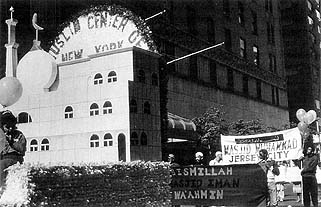

The Queens Muslim Center

The mosques that float down Lexington Avenue may be recognizably famous structures such as the Dome of the Rock or they may be prototypical mosques in high architectural style. However, the fourth mosque float in the Muslim World Day Parade in 1990 represented the future Queens Muslim Center. This float is the point of departure for my inquiry into the nature of storefront mosques (fig. 39). The float is the only currently realized form of that mosque, which otherwise exists only as a hole in the ground in Flushing in the Borough of Queens.

Figure 39. The 1991 Muslim World Day Parade: Float of the Queens Muslim Center, with sign of the basmala (In the name of Allah, the compassionate, the merciful). Photograph by Susan Slyomovics.

The Queens Muslim Center was founded in June 1975 by Hanafi Sunni immigrants from Bangladesh, Pakistan, and India, in a rented apartment on Forty-first Avenue in Queens. The center is situated in the well-to-do middle-class neighborhood of Flushing, where the other predominant ethnic group is the flourishing Chinese community, estimated at seventy thousand strong. In 1977, the center was incorporated as a nonprofit tax-exempt institution, and by 1979, members had purchased a one-family house for $75,000 in cash. The adjacent house was purchased shortly afterward, and the two structures were razed for the new building. Groundbreaking for the new building took place on May 21, 1989. Photographs of the event prominently feature the presence of the imam of the Ka‘ba, Sheikh Saleh bin Abdullah bin Homaid of Saudi Arabia, flanked by then Mayor Edward Koch.

While awaiting the completion of their new structure, the members meet in a two-and-a-half story, gable-roofed house located around the corner at 137–63 Kalmiah Street. The temporary quarters of the Muslim Center has room for only two hundred members. The carved wooden door leads to an enclosed porch with shelves for storing shoes and a bulletin board for written notices. From the porch, a staircase leads to the upstairs women’s section. The downstairs is completely opened up, except for the kitchen wall entrance. The interior is carpeted and strips of tape orient the worshipper to Mecca. A pulpit made from kitchen cabinets and two wooden steps surmounted by a simple flat, wooden domelike ornament creates a minbar (pulpit or seat). Markaz (“The Center”), the magazine published by the Queens Muslim Center, describes a new building with room for five hundred and fifty people to pray in the main mosque, outside halls with room for one thousand six hundred people, another community hall seating four hundred, a kitchen, an Islamic school, and a gymnasium offering lessons in martial arts and the Qur’an. When it is finished, the Muslim Center will be an instance of successful transition from rented apartment to purchased house (both of them makeshift “storefront” expedients) to architecturally purposeful mosque and community center complete with designed dome, crescent moon, and minaret, the kind of mosque now typically preferred in the diaspora (cf. Haider, this volume).

The Queens Muslim Center embodies the aspirations of many, although not all, Muslim communities in New York City. These are best articulated by Levent Akbarut in “The Role of Mosques in America,” an article written for The Minaret, a widely circulating newspaper based in East Orange County, California, and excerpted in Markaz (1990). Akbarut argues that the American mosque, in contrast to mosques in the countries of origin, needs to be a school, because urban schools are substandard; a community center, because the streets are dangerous; and a locus of political activity, such as voter-registration drives, so that Muslims will have a say in the decision-making processes of this country (cf. Eade, this volume). Quoting a saying, or hadith, from Al-Bukhari, the author acknowledges that “a mosque within the confines of four walls and a ceiling is not a requirement for a Muslim community to offer prayer, because God has made the whole earth a sanctuary for worship.” Why then, he asks, did the Prophet build a mosque during the Medinan era? The answer is that the mosque functioned as a center of Islamic affairs and organization and thereby nurtured and sustained the Islamic effort. This example should be kept in mind by Muslims seeking to establish Islam in America (Akbarut 1986: 10). What the author envisions is precisely what the Muslim Center in Queens hopes to achieve: not only a mosque, but a building that unmistakably declares what it is, as opposed to the unmarked Queens house that currently functions as a mosque.

Masjid Al-Falah, Corona, Queens

This same theme is evident in the building of a second Hanafi Sunni mosque located in Corona, Queens, a lower-middle-class neighborhood populated primarily by Spanish-speaking immigrants from Central and South America. Masjid Al-Falah, at 42–12 National Street, began as a rented storefront carved out of a three-story wooden house in 1976. (The storefront is now occupied by a Pakistani restaurant, the Mi‘raj, whose proprietor is active in the mosque.) The mosque membership then purchased the lot across the street, where a single-story mosque structure was completed in 1982.

Masjid Al-Falah was given a building prize by the Borough of Queens. It holds approximately seven hundred and fifty people, but there are plans for two additional stories, a dome, and a forty-foot-high minaret. Only the base of the minaret has been laid out, because a forty-foot minaret is not certain to obtain a borough building permit. Although the Queens Muslim Center has received borough permission for minarets and domes, its muezzin and the sounds of the call to prayer must remain electronically unamplified, and out of deference to the secular authorities, the Corona mosque’s imam likewise uses only the power of his voice to summon worshippers.

In this case, the architectural goals derive not from the membership but from the builder, William Park, a Korean construction engineer who was at one time chief engineer of Korean construction crews in Saudi Arabia and Iraq. (The architect named on the billboard outside the project, Jone Jonassen, is in fact a “front,” since a valid architect’s license is needed to file the plans.) Park says his designs are based on his own impressions of the composite mosque architecture that he saw and helped to construct in the Gulf states. Thus, the architectural tastes of the oil-rich countries, filtered through the sensibilities of a Korean crew working in Saudi Arabia, have also immigrated on a smaller scale to New York.

Al-Fatih Mosque, Brooklyn

A third example of transforming structures designed for other purposes into an acceptable mosque is the Turkish Al-Fatih mosque located in the multi-ethnic Sunset Park district of Brooklyn at 5911 Eighth Avenue. Serving some five hundred and fifty members, the building, purchased in 1979, provides space, not only for prayer but also for a school on weekends, a women’s organization, youth clubs, and student cultural activities. The mosque is located on a block that houses a series of Turkish businesses whose storefronts fill half of the block, among them a halal grocery for Middle Eastern foods and a business that acts as a cultural and linguistic broker for the local Turkish-speaking community by providing income tax, realty, air travel, and translation services. Sunset Park’s ethnic diversity is evident in the adjacent block, which houses a Japanese hairdresser, a Buddhist storefront temple, and a Chinese bookstore and restaurant.

The Turkish mosque was originally a movie theater, designed, as many American movie houses have been, as a Hollywood amalgam of Orientalist-Moorish-Arabesque fantasies (cf. Haider, this volume, fig. 6). The conversion of the movie house into a mosque reclaims the Orientalist style, invests it with new meaning, and literally reorients the building. The exterior portals have been refashioned by a Turkish carpenter, Irfan Altinbasak, to form semicircular arches. New American-made plastic-based Turkish-styled tiles are being used to replace the original Iznik tiles, dislodged one by one by the inclement New York City weather, to redecorate the exterior.

As worshippers enter on the left, they encounter the former ticket booth area, now converted to a religious bookstore, while on the right-hand side, there is a wall decorated with beautiful Turkish tiles from Iznik. Although a donor’s name might be calligraphically acknowledged on mosque walls in Islamic lands, it is a distinctly American touch to set up a wall of donors: eventually each tile will carry the name of a donor who contributed to the establishment of the mosque. What was once the lobby of the movie house is now divided into sections by a series of arcades layered with marble added by the Turkish carpenter, a genuine Oriental addition to the original Oriental decor. The arcades serve no structural purpose but provide a decorative and emotional tone. Once, the Oriental touches made the movie theater feel like a luxurious, privileged space, set off from ordinary life; what they do now is “to make the interior feel like a mosque,” as the Turkish leaders informed me.

The main part of the praying area is the actual screening auditorium, the back wall of which serves as the qibla, with a wooden minbar and a tiled mihrab. The stage where the screen once was has become a cordoned-off women’s section. The Turkish mosque is thus a very powerful reinscription of interior space: American moviegoers once faced in the opposite direction to present-day Muslim worshippers, who literally turn their backs on the space where sex goddesses were once displayed on the screen, which is instead now occupied by women screened off from view.

Curvilinear, draperylike forms overhang the stage and have been highlighted and emphasized by painted designs. The carpeted interior is bare, with the exception of two model mosques. One is used as a collection box, and the second, evoking the minaret skyline of Istanbul, is placed on a raised dais; no explanations were given to me for its presence. Amplification is only permitted in the interior of the mosque. The imam expressed a wish for an exterior dome and a minaret, but here, too, there had been difficulty in obtaining the necessary building permit.

Creating Mosques: The Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens

Several other examples illustrate the transformation of buildings into mosques. The Islamic Sunnat-ul-Jamaat, a Hanafi Sunni mosque in the Bronx at 24 Mt. Hope Street was created by English-speaking Guyanese immigrants of Indian Muslim descent. Beginning in a basement on the Grand Concourse in 1978, they purchased a three-story single-family building in 1988 for $45,000 and now have 500 paying members, among them a minority of West Africans. They now plan to buy the adjacent building in order to be able to accommodate the three to four thousand worshippers they hope to have. They have marked the entrance to their mosque as sacred space by a sign in Arabic with English transliteration: “O God, open to me the doors of your mercy.”

The interior staircase separates men praying on the first floor from women on the second. Interior walls and partitions have been gutted; as in other American mosques, masking-tape guide lines run the length of the first and second floors to orient worshippers toward Mecca. On Sunday, October 7, 1990, the Prophet’s birthday (Mulid an-Nabi), a celebration was combined with the annual general meeting and election of mosque officers, thus complying with New York State rules for nonprofit organizations and combining ritual and business. The members videotaped the event, not only for themselves, but for their families back in Guyana, who could thus see the building and the celebration. The four-hour celebration ended with a homecooked meal of Indian, West Indian, and West African cuisine served upstairs to the women and outside to the men.

Two true storefronts in Brooklyn exemplify modest transformations to create appropriate mosques. The Masjid Ammar Bin Yasser, at Eighth Avenue and Forty-fourth Street in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park, is a storefront of a building owned and inhabited by a Palestinian family from Ramallah. Most of the two hundred and fifty members are Palestinian, Lebanese, and Jordanian. The first-floor mosque and the basement school, named after Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, have been operating since 1986. The interior space was transformed into a mosque by cutting two large semicircular arches into the wall that formerly divided the space in two and by turning the two interior doorways that once opened into the next building into mihrabs, one signaled by a carpet, and the second more elaborately by a carpet and tiling and by the installation of a minbar. On the outside, varnished wooden slats have replaced the storefront windows. Most poignantly, signs depicting a dome and minaret stand in for the absent, prohibited structures.

The second nearby storefront mosque, Masjid Moussa Bin Omaer, is situated on Fifth Avenue near Sixty-second street in Brooklyn, an area of three-story single-family homes whose bottom floors were converted to storefronts as the street became a commercial thoroughfare. The mosque has rented space since 1987, and its interior is protected by white-painted wooden planks, now covered with graffiti. The members of the mosque, mainly Egyptians and Palestinians, did not wish me to photograph the interior because they had just begun to build and felt, therefore, that this was not yet a real mosque and should not be documented.

Similarly, one of the members of the Masjid Al-Fatima in Woodside, Queens, interrupted my interior picture-taking. The Al-Fatima mosque occupies the basement, rent-free, of a commercial building and storefront owned by a Pakistani, who runs a fleet of taxis from the rest of his building. The downstairs uses alternating strips of colored carpet to orient the worshipper to Mecca. The minbar is a simple carpeted step. The entrance to the basement mosque is again signaled by a green-painted carved dome with a sign.

The Turkish-Cypriot mosque in Morris Park, the Bronx, is the former rectory of a Protestant church. The new owners put their imprint on the front of the building by appropriating decorative techniques of Italian-American grillwork on window frames for their latticelike, nonfigurative qualities and then transforming the side square windows with cardboard inserts, two visual display techniques suggesting Islamic not Gothic arches.

Mosques have also been created from suburban homes in Queens (for example, a one-year-old Afghan mosque marked only by its discreet sign); from a five-story commercial warehouse (Masjid Al-Farouq on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn); from a Brooklyn Heights townhouse (Masjid Daud, established in 1936); from a commercial warehouse (by Crimean Turks, who are located in the otherwise entirely Orthodox Jewish Hasidic neighborhood of Borough Park in Brooklyn); from a former dentist’s office (in the Queens neighborhood of Jamaica); and from the basement of a storefront in the Bronx. This last example may be a first stage: the basement “storefront” mosque might expand upstairs to the actual storefront and eventually be replaced by a newly constructed mosque.

It should be emphasized that Muslims and mosques in the outer boroughs of New York City are regarded by non-Muslims as positive presences in a neighborhood, even in an insular Italian-American neighborhood like Morris Park. Dan Fasolino, the local Democratic district leader, a former New York City police officer turned realtor, tightly monitors neighborhood property sales. He claims to speak for the local community when he says that immigrant Muslims are hard-working, entrepreneurial, upwardly mobile new Americans. One does well to remember this, given that one storefront mosque acquired sudden prominence in the United States: the al-Salam mosque, currently occupying the third floor of a commercial building in Jersey City (New York Times, September 9, 1993). This is the mosque associated with Sheik Omar Abdel-Rahman, who is alleged to have been implicated in the bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993.

| • | • | • |

Conclusion

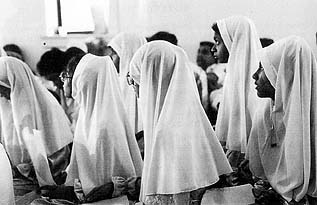

A song sung by the female students of the Sunnat-ul-Jamaat mosque in the Bronx on the occasion of the Prophet’s birthday (fig. 40) suggests themes in Muslim self-representation in New York City shared by mosque architecture as well. The melody was a southern railroader’s dirge made famous during the folk-song revival of the early 1960s by groups such as The Journeymen, The Kingston Trio, and Peter, Paul and Mary. It also became famous under the song title “Five Hundred Miles”:

| If you miss the train I’m on | |

| You will know that I am gone | |

| You can hear the whistle blow 500 miles | |

| 500 miles, 500 miles | |

| Lord I’m 500 miles away from home | |

| Not a shirt on my back | |

| Not a penny to my name | |

| Lord I can’t go back home this-a-way |

Figure 40. Young students at the Sunnat-ul-Jamaat mosque in the Bronx. Photograph by Susan Slyomovics.

The Peter, Paul and Mary version was a worldwide best-selling record, and clearly it must have been heard in Guyana. The original American verses speak of the adventure, the poverty, and the romance of the lonesome road that never reverts back home. The new Muslim lyrics make a different use of the metaphor of life as a road: “Do you know what Islam says / It says life’s a big big chance / It says that life is a far road space / Return upon rest.” The words of the chorus replace “This-a-way, Lord I can’t go back home this-a-way” with “A way of life, Islam is a way of life, a complete way.”

The melody, a kind of architectural framework, is given, but the content is new. Similarly, a pamphlet describing the Shi‘ite mosque services, which was pressed into my hand by the Iraqi imam of the Brooklyn Shi‘ite temple during the bombing of Baghdad by the United States and its allies in the Gulf War, bears this legend superimposed on a map of the United States: “This is our destiny, let us make it.” Muslims express their culture in new ways within the space and institutions of their larger sociopolitical world.

The movement I am charting begins with interior space gutted, transformed, and even acoustically reconfigured to Muslim sacred space, then expands outward according to the increased membership and prosperity of the community, and finally triumphantly rewrites American locales, either transiently, as for the Muslim World Day Parade, or permanently, as in the case of the new Manhattan All-Muslim mosque on Third Avenue and Ninety-sixth Street, between the Upper East Side and Spanish Harlem, officially serving all of New York City (fig. 4, this volume). While Muslims would acknowledge that a mosque requires little more than a property or rented space, many seek such impressive buildings. One of the members of the Guyanese Bronx mosque said to me that their mosque in the Bronx, the Sunnat-ul-Jamaat, was not a real mosque. The real mosque was a picture appliqued on her purse depicting a Saudi mosque. A real mosque, she said, had a minaret and a dome and was richly decorated inside and outside. Her description in fact resembled the official All-Muslim mosque.

We can never be sure, when using architecture or vernacular architecture to “read” contemporary ethnicity, whether a given reading accurately interprets what is being said. Even though architectural phenomena are hard and objective, their meanings are soft and ambiguous. Architecture represents social meaning. Physical space also affects its occupants. For example, do Turkish worshippers in a transformed Oriental-style movie house come to think of themselves as “Oriental”?

New York City is a center of cultural production, a process that has been more laissez faire in the United States than in Europe. Ritual prayer and creating spaces for that prayer have been central activities in Muslim community life. In the Muslim World Day parade—featuring, above all, mosque replicas—and the new mosques, Muslims are finding ways to create new communities while inserting themselves into this particular state and its larger society. This is a process that leaves both sides changed.

Works Cited

Akbarut, Levent. 1990. “The Role of Mosques in America.” Markaz: Journal of the Muslim Center of New York (Groundbreaking Special Number) 12: 10–12. Reprinted from The Minaret, November–December 1986.

Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, eds. 1983. The Invention of Tradition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kasinitz, Philip, and Judith Friedenberg-Herbstein. 1987. “The Puerto Rican Parade and the West Indian Carnival.” In Caribbean Life in New York City: Sociocultural Dimensions, ed. Constance R. Sutton and Elsa M. Chaney, pp. 327–50. New York Center for Migration Study.

Kelton, Jane Gladden. 1985. “The New York City St. Patrick Day’s Parade: Invention of Contention and Consensus.” Drama Review, no. 29: 93–105.

Kugelmass, Jack. 1991. “Wishes Come True: Designing the Greenwich Halloween Parade.” Journal of American Folklore 104: 443–65.

Rudofsky, Bernard. 1964. Architecture without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Slyomovics, Susan. 1995. “New York City’s Muslim World Day Parade.” In Nation and Migration: The Politics of Space in the South Asian Diaspora, ed. Peter van der Veer, pp. 157–76. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.