| • | • | • |

The Bai‘tul Islam Mosque, Toronto, and Back to Wimbledon: Externalizing Islam

The demand for what is seen as visual authenticity in the mosque, however, has intensified over the past decade. On the one hand, this is a natural sign of the maturation of the first wave of postwar immigrants, many of whom came for education and then settled for better economic and professional opportunities. On the other hand, this is also a sign that efforts at “melting into the pot” have given way to assertion of a Muslim identity as a better alternative. There are also global movements afoot that have given Muslims in the diaspora a sense of identity and linkage as part of the umma, or worldwide Muslim community. Some have now started to express “dome and minaret envy,” in relation, for example, to the Plainfield mosque.

These years have also been a period of intense energy in architectural-academic discourse as modernism started to come under questioning and later open attack. The word postmodernism came to evoke everything from zealous commitment to ridicule. New terms such as postfunctionalism,poststructuralism,deconstructivism,logocentricism, and even reconstructivism made their appearance.

Even so, the postfunctionalist search for “meaning” and the return of “philosophical inquiry” through architecture has been timely for the emergent discourse on sacred architecture. For Muslims, there has been much discussion about the value of the Islamic heritage within a technologically homogenizing world. The symposia of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, in particular, have brought the protagonists of tradition and those of modernity around the same table under the mostly civilizing gaze of some philosophers and itinerant sages. These symposia have taught me to treat my most cherished architectural conceptions with a humbling doubt.

For me, the academic inquisition against modernism has provided numerous opportunities. As the design canons of modernist minimality and pure composition have come under attack, there has been a new air of respectability for the study of ornament, craft, tradition, form, symbol, text, inscriptions, and, above all, the philosophical underpinnings of architectural intentions. There is now legitimacy for seeking to know culture though the direct experience of art—“tactile knowing,” as we ended up calling it. It was the interpretive drawing of carpets, miniatures, and gardens, as well as the recitation of poetry, that opened up Islamic culture for many of my Canadian students.

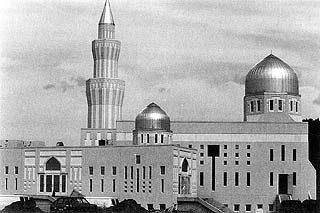

In 1987, almost ten years after the ISNA mosque, I received a commission to design a large mosque in Toronto. By then, numerous North American Muslim communities had shown a desire for assertion through architecture, rather than anonymity through dissimulation. This desire was particularly keen in this case: the mosque was to be the national headquarters of the Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam, a community declared out of Islamic bounds by act of the Government of Pakistan in 1974, which now, quite simply, wanted all the architectural help it could get to express its Islamic presence in Canada (Haider 1990). I was advised to reject this commission, lest I risk my future and never get another job, or even risk my hereafter by “partnership in the crime of Ahmadiyyat.” I am not an Ahmadi Muslim, and I am not qualified to make pronouncements on Islam or meter others’ Islamicity. I am convinced, however, that I have designed a mosque, and that what are performed there are prayers in the finest tradition of Islam.

In designing the Toronto mosque, I used the prayer rug as a conceptual inspiration, as well as a source of formal and decorative discipline. Conceptually, the prayer rug, as it is spread out and qibla-directed, defines the elemental place of prayer. As the believer positions and orients his or her body on it and goes through various stages of salat, the Islamic ritual prayer, a place-space is defined, in the physical and temporal as well as experiential sense, that has all the essential attributes of a mosque. As the prayerful body interacts with the qibla-directed Cartesian planes established by the prayer rug, so the collectivity, the parallel rows of the community of believers, resonates with the architectural space of the mosque. All design decisions, especially the proportions of the space, the pattern and the placement of fenestration, the sequential placement of entrance and arrival, tile patterns and carpet layout are aimed at achieving this resonance. The prayer rug rises out of its horizontal plane and wraps itself around the space.

This mosque started with the study of prayer rugs; and its final act of design resulted in a prayer rug that has been sand-etched in the glass of the doors marking the entrance to the prayer hall. If the Plainfield mosque might seem like a corporate headquarters to the freeway observer driving by, the Toronto mosque boldly asserts an Islamic profile, reclaiming the conventional minaret and dome for their appropriate ends (fig. 9).

Twenty-five years after the first encounter, I had a chance to visit Wimbledon again. The house-mosque was now wrapped with a glazed finish; arched windows sat squeezed into what were at one time rectangular openings; the parapet had what seemed like an endless line of sharp crescents; and there were a number of token minaret domes, whose profile came less from any architectural tradition than from the illustrations of the “Arabian Nights.” By now, they, too, had felt compelled to “Islamize” that sometime English house.

My innocent but bizarre encounter with the “Syria Mosque” has never left me. Like a plow in the field, it turns inside out what would otherwise have been quiet, sedate, but decaying chambers of my mind. I have never ceased raising questions about what a North American mosque might be and become. The mosque will have to attain its rightful and self-assured place in world society, so that later generations who choose to come to North America will not be faced by a theater garbed in Moorish dress.

Muslims living in the non-Islamic West face an unparalleled opportunity. Theirs is a promising exile: a freedom of thought, action, and inquiry unknown in the contemporary Muslim world. They are challenged by a milieu that takes pride in oppositional provocations. Those who can break free of the inertial ties of national and ethnic personas will be the ones who will forge an Islamicity hitherto unexperienced. They have the freedom to question the canons of traditional expression. Their very exile, understood as separation from the center, will make the expressions of Islam more profound, whether in literature, music, art, or architecture.

Muslim minorities in the non-Muslim world will ultimately realize that their history has put them in a position somehow reminiscent of the Prophet’s Meccan period. Their isolation will purify and strengthen their belief. It will refine their thought and make their tools precise, and at an appropriate time, they will start to send “expressive” postcards home. Then there will begin another migration, not in space and time, but from blindness of a certain kind to a clearer vision, from spiritless materiality toward expressive spirituality.