10. Karbala as Sacred Space among North American Shi‘a

“Every Day Is Ashura, Everywhere Is Karbala”

Vernon James Schubel

Karbala holds a place of central importance in the piety of Shi‘i Muslims. As the place where the Prophet Muhammad’s beloved grandson Husain was martyred in 680 C.E., Karbala is simultaneously the site of a particular historical tragedy and the location for a metahistorical cosmic drama of universal significance. In the United States and Canada, the ritual evocation of Karbala helps Shi‘i Muslims construct a unique and meaningful identity in the midst of an “alien” environment. By creating spatial and temporal arenas for the remembrance of Karbala, the Shi‘a consciously adapt and accommodate existing institutions such as lamentation assemblies and processions in ways that allow them to claim space through the expression of central and paradigmatic symbols.

This essay explores the role of Karbala as a “sacred center” for Shi‘i Muslims in the context of a particular North American community. The research was conducted primarily at the Ja‘ffari Islamic Center in Thornhill, Ontario, in July and August 1990.[1] The Ja‘ffari Center is a Shi‘i institution whose buildings are located on a major traffic artery in the Toronto suburbs. It serves the spiritual needs of a large community of Urdu- and Gujarati-speaking Shi‘a, consisting largely of immigrants from East Africa.[2] The community’s members live dispersed throughout the Toronto area. The community is relatively affluent, the majority of its members having successfully made the transition to become suburban residents in the modern Canadian “ethnic quilt” (cf. Qureshi, this volume).

Living as members of a religious minority group is nothing new for the Shi‘a. In most parts of the Muslim world, the Shi‘a constitute a religious minority who live their lives physically surrounded by other communities who reject many of their beliefs and practices. The Shi‘a of the Ja‘ffari Center are also an ethnic, as well as a religious, minority, a situation familiar to the Gujarati Khojas, the majority of members of the center, who migrated from East Africa. They must decide which elements of the cultures of their countries of origin they will preserve. For most, their Shi‘i identity is primary.

The remembrance of the battle of Karbala as a significant historical and religious event is crucial to the way in which Shi‘i Muslims maintain their unique identity within the larger ummah. The importation of rituals for the remembrance of Karbala has also facilitated the community’s adaptation to the Canadian environment. The remembrance and re-creation of Karbala allows the Shi‘i community to claim space in North America that is both North American and Islamic: they thus Islamize elements of North American culture while creatively adapting Islam to the North American environment.

| • | • | • |

The Nature of Shi‘i Piety

Shi‘i piety is firmly oriented toward a historically focused spirituality that seeks to understand the divine will through the interpretation of events that took place in human history. Important events in the early history of Islam, such as the battle of Karbala, are understood as “metahistorical,” in that they are seen to transcend and interpenetrate ordinary reality, providing definitive and dramatic models for human conduct and behavior. While this is true to some degree for all Muslims—as well as for Jews and Christians—the Shi‘a place a distinctive emphasis on this aspect of piety, evident in rituals like the one described below.

Shi‘i Islam can be described as the Islam of personal allegiance and devotion to the Prophet Muhammad. As one important Shi‘i thinker in Pakistan explained it to me, whereas both the Sunni and the Shi‘a accept the authority of the Prophet and the Qur’an, the Shi‘a believe that the Qur’an is the Book of God because Muhammad says that it is, and he can never lie; in contrast, the Sunni believe that Muhammad is the Prophet of God because the Qur’an identifies him as such (Waugh et al. 1991; Schubel 1993).[3] Thus, although Sunni Islam emphasizes obedience to the Qur’an as the fundamental basis of Islam, the Shi‘a, who also fully accept the authority of the Qur’an, categorically reject Umar’s statement at the deathbed of the Prophet that “For us the Book is sufficient.” The Shi‘a argue that the Qur’an can only be properly interpreted by Muhammad and his family (Ahl al-bayt), who specifically include the Prophet’s daughter Fatima, his son-in-law ‘Ali, their two sons Hasan and Husain, and, for the Ithna’ashari majority of the Shi‘a, a series of nine more imams (the first three being ‘Ali, Hasan, and Husain), culminating in the hidden twelfth imam, who will eventually return to establish justice in the world. For them, Islam requires allegiance, not only to Muhammad, but also to the twelve imams, to whom God has given divine responsibility for the interpretation of the Islamic revelation.

The Shi‘a also typically claim to be distinguished by their special emphasis on the necessity of love for the Prophet. Muhammad is the beloved of God (Habib Allah). Thus, if one wishes truly to love God, one must also love the Prophet whom God loves; one must further demonstrate that love by expressing love and allegiance for those whom the Prophet loved. This is particularly true of those closest to the Prophet in his own lifetime—Fatima, ‘Ali, Hasan, and Husain. For the Shi‘a, the events of their lives form the ultimate commentary upon the Qur’an.[4] These events carry with them a reality and a meaning that transcends and encompasses all of human and spiritual history.

The most important of these events is undoubtedly the martyrdom of Husain at the battle of Karbala. Vastly outnumbered and cut off from food and water, the last remaining grandson of the Prophet was brutally slain in combat at Karbala, having first watched his close family members killed by the troops of Yazid b. Mu‘awiyah, the man who claimed to be the rightful caliph of Islam. Husain, who as a child had climbed and played upon the back of the Prophet, was decapitated; his body was trampled on the desert floor. The women of his family, the surviving witnesses to the slaughter, were marched in shackles before Caliph Yazid in Damascus. Husain’s head was carried into Damascus on a pole. Given the atrocities committed against the Prophet’s family, from the Shi‘i perspective, the community of Islam divided once and for all at Karbala between those who accepted the necessity of allegiance to the Ahl al-bayt and those who rejected it.

The importance of Karbala for the Shi‘a finds its fullest articulation in numerous rituals that orient the community toward the events that took place there. Indeed, many South Asian cities contain areas called “Karbalas,” in which ritual objects such as ta‘ziyehs (replicas of Husain’s tomb) are buried. Annual commemorations of Husain’s martyrdom at Karbala during the first ten days of Muharram are essential to Shi‘i piety. These include mourning assemblies (majlis-i ‘aza) and processions (julus). Such activities, collectively known as ‘azadari, are occasions for the ritual re-creation of Karbala. Karbala is ritually portable, and South Asian immigrants have carried it with them to the North American environment.

Karbala is linked both to a place and an event. As such, its re-creation involves the transformation of both time and space. The re-creation of the place of Karbala is typically accomplished through the establishment of buildings dedicated to Husain called imambargahs, which are community centers where a number of functions are carried out, including devotional rituals, community education, and the preparation of the dead for burial. The re-creation of sacred time is accomplished by the cyclical commemoration of important events in the lives of the Ahl al-bayt as they appear on the Shi‘i calendar through rituals of zikr (remembrance) and shahadat (witness).[5]

As Professor Abdulaziz Sachedina—an important figure in the community—stated during a majlis in Toronto, the Shi‘a believe that it is incumbent upon Muslims to remember the ayam-i allah (Days of God).[6] For the Shi‘a, of course, these ayam include the days of Karbala. Optimally, the remembrance of Karbala should be integrated into the everyday lives of the Shi‘i community. From the Shi‘i perspective, the whole world continuously participates in Karbala; it is as if the events of Karbala are always taking place just below the surface of ordinary reality. Devotional ritual allows devotees to cut through the veil that separates them from Karbala so that they can actually participate in it. “Every day is Ashura, and everywhere is Karbala,” banners carried in the Muharram processions in downtown Toronto declare.

The ritual re-creation of Karbala creates an environment that in Clifford Geertz’s terms can “establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing those conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic” (Geertz 1973). But Shi‘i devotional activities not only, ideally, instill the assurance that the “system of symbols” encountered in Shi‘i ritual is a “uniquely realistic” model of and model for reality, they can also challenge believers to compare the state of their lives and their society with the paradigmatic actions of Husain and his companions at Karbala. Thus encounters with Karbala serve as opportunities for individual and communal reflection. Devotional activities serve not only to reinforce the unique authority of Shi‘i Islam but also to encourage the creative adaptation of the community to changing circumstances.

| • | • | • |

The Imambargah as “Sacred Space”

Imambargahs in North America serve both to evoke Karbala and to publicly claim space by creating an Islamic presence in the midst of the alien “West.” Imambargahs are tied to Karbala as a sacred place by decorative symbols that draw one’s attention to God, the Prophet, and the Ahl al-bayt. When imambargahs are established in buildings originally designed for other purposes, only the interiors of these buildings are transformed into recognizably Islamic places.

On the other hand, when a community has the opportunity to build its own structure, it must decide to what extent the building will participate in a “Western” aesthetic. In the case of the Ja‘ffari Center, which was built in 1978, an architect was hired with explicit instructions to construct a recognizably Islamic building, and yet one lacking such characteristic features as domes and minarets, which might make it stand out too abruptly from the local architecture (cf. Haider, this volume). The completed building is a remarkable edifice, which is recognizably Islamic and yet part of the Canadian architectural landscape. It represents an Islamization of local architecture that mirrors other attempts by the community to find ways to Islamize the local environment—for example, using English in majlis. Imambargahs are therefore places where an indigenous North American Islamic aesthetic is being created.

The Ja‘ffari Center is situated amidst other religious edifices, including a Chinese Buddhist Temple and a Jewish synagogue—both of which provide extra parking for the center during Muharram. On its main level, the center contains a large hall for majlis, called the Zainabia Hall, and a masjid (mosque). Upstairs are a library and a large room for women with children. Women can participate in majlis from a large room located downstairs.

The centrality of spiritual history and allegiance to the Ahl al-bayt are clearly evident in the architecture and decoration of the building. The very names of the component parts of the structure evoke the presence of the Ahl al-bayt. For example, the majlis hall is named for Husain’s sister Zainab. This is significant, since the hall is used for the purpose of bearing witness to the events of Karbala just as Zainab, as a survivor of Karbala, bore witness to the generation of Muslims immediately following those events. A sign notes that the foundation stone was laid by Dr. Abdulaziz Sachedina on the day of Ghadir Khumm, which commemorates Muhammad’s designation of ‘Ali as his mawla, which may be considered the founding of Shi‘ism itself.

The importance of sacred names and words is evident throughout the building. The majlis hall is flanked on one wall by ten glassed-in arches. The rear wall contains four more—two each on either side of a large arch-shaped window—for a total of fourteen. When I first saw the structure in 1982, these arches held bare glass. Within the past few years, stained glass bearing the word “Allah” in Arabic script and one of the names of the fourteen masumin (those protected from error)—Muhammad, Fatima, and the twelve imams—has been installed at the top of each arch. This hall is laid out towards the qiblah (the direction facing Mecca). At the end of the hall closest to the qiblah, there is a large archway connected to a skylighted alcove, which forms an open boundary between the hall and the masjid.

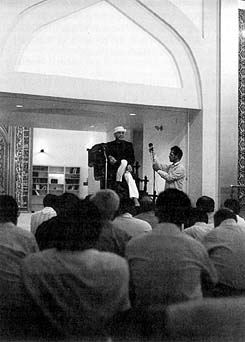

Recently, ornate pieces of Arabic calligraphy have been installed in the center. At the mihrab, there is a piece containing many of the ninety-nine names of God. In the hall itself, on either side of the archway leading to the masjid, there are two large pieces of calligraphy. One depicts the hadith in which the Prophet designated ‘Ali as his successor, the other a qur’anic verse reputed to refer to Husain. During the first ten days of Muharram, the zakir, or person who delivers the majlis, sits upon the minbar (a wooden staircase of about six or seven steps that serves as a pulpit near the qiblah) between these two signs of the Ahl al-bayt’s authority to deliver his majlis (fig. 34).

Figure 34. The majlis hall at the Ja‘ffari Center in Toronto, showing minbar flanked by calligraphy. Photograph by Vernon Schubel.

[Full Size]

At one end of the hall, there is a room labeled zari, which contains replicas of the tombs of the imams (ta‘ziyahs) and other pictures and objects evocative of the Ahl al-bayt. There are also containers for making monetary offerings in the name of the imams, ‘Ali, or the Ahl al-bayt.

All these features serve to evoke the central paradigm of Shi‘i piety—allegiance to the Ahl al-bayt. The physical environment of the building continually draws one’s attention to the necessity of that allegiance by constantly evoking Karbala in both the spatial geometry and the decoration of the center. Karbala is thus always present within the imambargah. During the first ten days of Muharram, the presence of Karbala is intensified through the performance of devotional rituals.

| • | • | • |

Muharram 1411: Devotional Activities at the Ja‘ffari Center

Large crowds of people came to the center for the Muharram activities—an estimated three thousand people attended on Ashura day, the tenth, alone. They came to attend the religious performance called majlis, when people gather to remember and mourn in a structured way the deaths of the Ahl al-bayt. Majlis may be held quite frequently, but they are most intense during the first ten days of Muharram immediately following the evening prayer. The crowd assembles in the majlis hall facing the minbar. Immediately before the actual majlis, poetry (marthiyah) recalling Husain is recited in Urdu.

The zakir’s sermon from the minbar seeks to inspire his audience with a sense of mournful devotion to the Ahl al-bayt. The majlis begins with the quiet communal recitation of Sura Al-Fatiha, the first chapter of the Qur’an. This is followed by the khutba, a formulaic recitation in Arabic consisting of praise of God, the Prophet, and the Ahl al-bayt. At the center of the majlis is the zakir’s presentation of a religious topic. This portion of the majlis generally begins with a verse from the Qur’an, with the rest of the zakir’s discourse acting as an exegesis of that verse.

The last portion of the majlis is the gham, or lamentation, recitation of an emotional narrative of the sufferings of the family of the Prophet. During each of the first ten days of Muharram, the content of the gham is traditionally linked to a specific incident at the battle of Karbala, which is recounted by the zakir. For many people, the gham is the most important portion of the majlis. Members of the congregation begin to sob and wail at the beginning of the gham. The mourning becomes more and more intense as the incidents of Karbala are recounted. People may strike their chests and foreheads. The gham ends with the zakir himself overcome with tears and emotion.

On certain days, the gham is followed by matam, the physical act of mourning. The performance of matam is exceedingly emotional. From the seventh through the tenth of Muharram, the matam is prolonged. Rhythmic and musical variations of poetry are sung by young men standing near the minbar, while the crowd joins in a calling pattern of repetition. The rhythm of the matam is carried by the metrical striking of the hands against the chest.

On the last four days of these rituals, the matam is preceded by small julus, or processions, within the imambargah itself. Symbols that evoke the stories of the martyrs of Karbala are carried through the crowd in the majlis hall. These take many forms: coffins draped in white cloth colored with red dye, as if bloodstained; a cradle representing the infant martyr ‘Ali Asghar; a standard bearing the five-fingered Fatimid hand, representing both the severed hand of the martyr Abbas and the five closest members of the Prophet’s family—Muhammad, Fatima, ‘Ali, Hasan, and Husain. The matam concludes with the recitation of ziyarat (visitation), in which the entire congregation turns in the directions of the tombs of the Ahl al-bayt and recites salutations to them. Ziyarat is the word used for pilgrimage to the tombs of the imams. As used here, however, it refers to Arabic recitations that serve as metaphorical visits to the tombs of the Imams. This is often followed by the communal sharing of food and drink before the congregation disperses.

These rituals focus the attention of their participants on the Ahl al-bayt and the necessity of allegiance to it. The didactic portions of the majlis are reinforced by the emotional power of the gham, matam, and julus, which follow. Through the gham, the community emotionally enters into Karbala. The fact that the ritual concludes with a metaphorical ziyarat, or visitation, of the places where the Ahl al-bayt are buried is significant. The majlis creates an actual encounter with Karbala and challenges the community to live up to its standards.

On this occasion, Ashura coincided with the 1400th anniversary of the events at Ghadir Khumm. The community commemorated the event with the publication of a book on the subject containing articles by a number of scholars (including Dr. Sachedina, who was serving as zakir). The importance of Ghadir Khumm in Shi‘i history prompted a good deal of discussion within the community around about the meaning of Shi‘i identity.

The main majlis was presented by Dr. Sachedina, himself a member of the East African immigrant community of Indian origin. Dr. Sachedina’s majlis made continual reference to Ghadir Khumm, as well as to Karbala. He presented his majlis primarily in English. Some of the content of the majlis dealt with topics that were seen as controversial in the community; at times his positions seemed to provoke some dissension. In response, Sachedina noted during his majalis that the minbar on which he sat was not his, but rather the twelfth imam’s—thus he believes that what he says as a zakir must conform to the message of the Ahl al-bayt, even if it makes members of the community uncomfortable. Since the majlis is presented in the memory of Karbala, it should challenge the community, just as the original incident at Karbala challenged the ummah.

Aside from the main majlis presented by Sachedina, there were earlier majlis by other zakirs and specific women’s majlis. A tent was erected adjacent to the masjid for special English-language majlis for the children and youth. A second tent was established to the west of the center that was used by the local Arabic-speaking Shi‘i community, consisting of Muslim immigrants from Arab countries, for their majlis. During the main majlis, men were seated upstairs in the main hall, whereas women were seated in a room below, facing closed circuit television sets, on which the majlis was broadcast.

The seating of men and women is a source of contention within the community. Sachedina several times raised the issue of gender partition from the minbar, which prompted much discussion after the majlis among members of the community. A member of the community told me that there was a time when men and women sat together for majlis; however, when other members of the community arrived from East Africa, where it was customary for the majlis to be fully segregated, they were shocked by this and demanded that there be a partition dividing men and women within the imambargah (cf. Qureshi, this volume). I was told that a fatwa (legal opinion) had been sought from the late Iranian Ayatollah Khui on this issue, and he had replied that if men and women dressed modestly, there was no need for segregation in the majlis hall. Those opposed to partition point out that whereas most of the women in the community practice some degree of modest dress, few practice full segregation except in the imambargah. If the imambargah becomes the only place in which purdah is practiced, it suggests that it is the function of the imambargah to preserve an East African identity rather than to create a North American Shi‘i one. More important, they argue, if the imambargah cannot be used to instill a sense of propriety of interaction between men and women, where will the youth of the community gain the training and discipline necessary to live in a larger society where they must interact with the other gender?

Another point of controversy in the community concerns the use of English as the language of the majlis. Sachedina made the decision to present the majority of his majlis in English, except for the gham, which he read in the traditional Urdu—which has long served as a lingua franca for South Asian Muslims, and has long been the language of the majlis for the Khojas who make up the majority of the congregation. Urdu is both a popular and a scholarly language with a highly developed literary tradition. The issue of the proper language for the majlis has been debated in the community at least since 1981. Many in the community believe that the majlis must be presented in Urdu, as English cannot convey the proper emotional timbre. Others argue that, since so few of the children can speak Urdu, an English majlis is a necessity if the majlis is to have any value for them. One concession to this has been made through the establishment of a children’s majlis in English.

Sachedina’s decision to present the entire ten days of the main majlis in English was in fact one that he felt he had to justify from the minbar. He argued that the topic of his majlis was more appropriately dealt with in English, even though it was on a theme aimed at adults rather than young people. Interestingly, teenagers tended to attend Sachedina’s majlis until the beginning of the gham. Then they would go outside of the hall either simply to gather in small groups or to listen to the English-language youth majlis. Sachedina had previously expressed the opinion in a series of majlis in 1981 that Urdu was not originally an Islamic language: it only became one as Muslims used it. He argued that English will only become an Islamic language when it is spoken by North American Muslims in religious contexts (see Note on Transliteration, this volume).

The controversies over language and gender partition both point to a central dilemma of this immigrant community: is the purpose of the center to preserve a particularly South Asian and East African form of piety within the community or to facilitate the emergence of a uniquely North American articulation of Islam? The younger generation are fluent in the popular culture of North America. They watch In Living Color and The Simpsons and are as fascinated by them as any other young people in North America. At the same time, they are drawn to the majlis both as a devotional ritual and as a way of making sense of their identity as Muslims in North America. Pride in Muslim identities was clearly evident, particularly in the instances when teenagers brought non-Muslim school friends with them to observe the majlis. The attendance of non-Muslims at the majlis underscores the value of the English majlis in creating common ground between the members of the community and other Canadians. Because of the emphasis on the ethical content of Shi‘ism, which resonates strongly with elements of Christian and European ethics, the English majlis simultaneously creates a common ground for Muslims and non-Muslims visitors within an explicitly Muslim arena.

Young people seemed especially interested in Sachedina’s approach to Islam, which takes the classical tradition very seriously while simultaneously recognizing the unique challenges of articulating Islam in the presence of modernity. Since discussions about the development of a distinctively North American articulation of Islam are not without controversy, the majlis provides an arena for discussions that might otherwise be too sensitive and divisive outside of the ritual confines of “sacred structure.”

| • | • | • |

The Blood of Husain

In addition to majlis, the re-creation of Karbala took other dramatic forms, such as the annual blood drive. Blood is an important symbol connected with Muharram. Husain is linked by blood to Muhammad, and the spilling of his blood on the field of Karbala is an act that is seen by the community as essential to the salvation of Islam. In South Asia, acts of ritual flagellation, called zanjir ka-matam, are commonplace; however this spilling of blood in remembrance of Husain is seen as problematic in the Western context.

Recent fatwas have shown that flagellation—while considered permissible—is nevertheless an act that is allowed only with the provision that it not be done in such a way as to bring embarrassment to Islam. Zanjir ka-matam is conspicuously absent from processions in North America. When I attended Muharram observances in 1986 at an imambargah located near a fast-food restaurant in New York City, the private practice of matam drew a large crowd of confused North Americans. The initial derision and amazement of American students when I lecture on this subject has demonstrated clearly to me the problem of explaining zanjir ka-matam in the West. Some of the people I talked to at the Ja‘ffari Center stated that they believed that such a practice was illegal in Canada. In any event, zanjir ka-matam was not performed at the center.

Instead, East African communities both in Pakistan and North America have engaged in an interesting transformation of blood-shedding in the memory of Husain. For many years, they have encouraged people to shed blood by donating it to blood banks. At the Ja‘ffari Center on the day of Ashura, the community set up a Red Cross blood bank and donated over 163 units of blood. Many more people were turned down because in view of the AIDS crisis, the Red Cross would no longer accept blood from people from sub-Saharan Africa.

One of the most interesting discussions within the community addressed from the minbar had to do with the issue of whether or not this blood could be given to non-Muslims. Sachedina argued on the basis of hadith that the imams had given water and food to people in need without asking first if they were Muslim or non-Muslim; thus blood donation to non-Muslims was allowable. The majority of the community seemed to share his opinion.

| • | • | • |

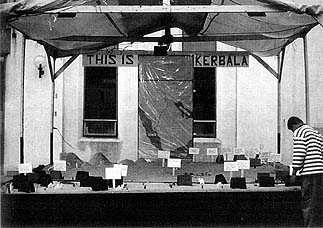

“This is Karbala”

During the Ashura period, a scale model of Karbala was erected outside along the rear wall of the center building (fig. 35). I was told that this custom had recently become popular in Tanzania and had made its way to North America in the past few years. The model battlefield was laid out in a wooden box filled with sand. A trench was dug through the sand to represent the river Euphrates. The tents of the forces of Husain, as well as those of Caliph Yazid’s general, ‘Umar, were erected in the relevant locations and marked with signs. Toy soldiers and horses were placed in different positions on different days to represent the changing circumstances of the combatants. Signs identifying the location of important events of the battle such as “Martyrdom place of Imam Hussein, Son of Ali and Fatema, Grandson of the Holy Prophet,” “Place of Amputation of the Left Arm of Hazrat Abas Ibne Ali,” and “Place where Ali Ashgar was Buried” were placed on the model battlefield. A roof was erected over the entire area, and a sign was hung over the model battlefield that stated “This is Karbala.” A large map on the back wall of the model showed the route Husain and his followers took from Mecca to Karbala.

On the last three nights, a cassette recording of Sachedina explaining the events of Karbala was played in the background. On Sham-i Ghariban, the night commemorating the struggles of the survivors of Karbala as they were marched toward Damascus, the model tents of the women were burned to re-create the actual burning of the tents, and wooden camels were arranged in a caravan to replicate the prisoners’ long march to Damascus. This model was primarily for the children, who in fact took a large part in arranging it. They seemed quite fascinated by it and could often be seen crowding around it.

| • | • | • |

Public Ritual: Julus in Toronto

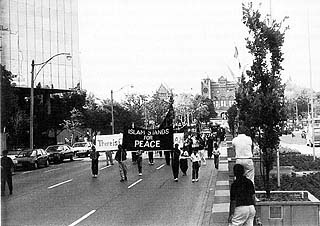

The remembrance of Karbala not only serves to educate the community (particularly the younger generation), it also provides for the education of outsiders, as a means of calling them to the “true” Islam—the Islam best exemplified in the lives of the Ahl al-bayt. Thus, acts of ‘azadari occur both within the center, primarily for the spiritual benefit and education of the community, and outside the center, for the education of the larger community. From the perspective of the participants, Karbala speaks to the humanity of all people, drawing them not only to ethical action, but also to the eventual acceptance of Islam. To this end, the community stages a yearly procession through downtown Toronto.

The julus was held on the 6th of Muharram. It began at roughly 3:00 p.m. on a Sunday afternoon, when the community gathered at Queen’s Park. Most of the community members, especially the women, were dressed in black. People carried banners and staffs, distributed water and other beverages, and handed out literature. In many particulars, the julus in Toronto mirrored similar processions in Pakistan, with a few important exceptions. There was no matam, and there was no horse representing Dhuljinnah, Husain’s mount; there were also no ta‘ziyahs or coffins. However, standards and banners similar to those found in Pakistan were present. Women marched separately from the men, at the rear of the procession, whereas in Pakistan women generally do not participate in processions. (The increased presence of women in community activities is a common theme throughout these essays.)

As in South Asia, the julus serves a number of important and interrelated functions. It enables the community both to reenact the Karbala paradigm and to display its religion to outsiders through such acts as distributing water, food, literature, and the presentation of speeches bearing witness to Karbala and its meaning. In Canada, this audience of outsiders is not only non-Shi‘a, but non-Muslim as well (cf. the processions described by Slyomovics and Werbner, this volume). Witnessing to this audience is problematic, given the ubiquitous stereotypes about Islam in American culture. The Muslim community is well aware of these stereotypes and the general lack of knowledge concerning Islam that produces them. It was no coincidence that the banner that led the procession read “Islam Stands for Peace,” a clear rebuttal of Western stereotypes about Islam as an inherently militaristic religion (fig. 36). As a matter of fact, despite the attempts of the community to use the julus for education about the religion of Islam, the press seemed more interested in asking questions about their reaction to the attempted Islamic coup that had just taken place in Trinidad. They were seemingly uninterested in the religious significance of the procession.

Figure 36. Banner proclaiming “Islam Stands for Peace” in a Toronto procession. Photograph by Vernon Schubel.

[Full Size]

The use of julus as an act of public ritual illustrates an interesting juncture between Shi‘i and North American culture. The julus has its origin in the Muslim world, and yet the act of people marching with banners in the downtown of Toronto seemed curiously familiar. In many ways, the julus of the Shi‘a could be seen by outside observers as simply another version of a secular activity, the parade. On one level, the community was simply bringing a ritual to Canada, but on another it was Islamizing the already familiar North American ritual of ethnic groups parading. This was even more obvious later in the week when the annual Caribbean Festival parade went through the streets of Toronto, with a distinctly different intent and atmosphere (cf. Slyomovics, this volume).

As a part of the educational function of the julus, members of the procession passed out a pamphlet entitled Islam: The Faith That Invites People to Prosperity in Both Worlds, which was clearly aimed at non-Muslims with little or no knowledge about Islam or Shi‘ism. It stressed the notion of peace in Islam and emphasized the common elements of the three monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It clearly elaborated a Shi‘i perspective, noting the need for an “authoritative leader in Islam who will guide the believers on the right path.” It further stressed the necessity of people rising in defense of God’s laws on earth, even to the point of martyrdom if necessary. The paradigmatic example of this martyrdom is, of course, that of Husain: throughout Islamic history, as a result of the battle of Karbala, “When rulers became oppressive, Muslims arose following the examples of Imam Husayn to demand Justice.”

This pamphlet presents its argument in a manner common in Shi‘i polemics; that is, it appeals to the universal human values expressed in the incident at Karbala. The root paradigms (Turner 1974) at the heart of the Karbala drama include such virtues as courage, honor, self-sacrifice, and the willingness to stand up against injustice and oppression. There is the conviction that the universality of these virtues may ultimately attract people to embrace Islam.

The procession, briefly diverted to avoid a gay and lesbian rights parade, made its way to a central downtown square, where a grandstand had been erected, from which speeches were read. There were few non-Muslims in attendance, but the ones who were there watched somewhat bemusedly from a distance. The presence of black-clad, modestly dressed women bearing a huge banner proclaiming, “Every day is Ashura, everywhere is Karbala” was, from the standpoint of non-Muslim Canadians, strikingly juxtaposed against the ultramodern architecture of downtown Toronto.

As with the majlis, the julus contained elements that made it clear that Karbala is not viewed as a past event that holds no meaning outside of its own time. One of the speeches that took place at this gathering deserves special mention in this regard. One of the speakers at the rally was a young black man who referred to himself as a Muslim who loved the Ahl al-bayt. He made a special point of noting that Husain had died to protect the rights of minorities and drew the community’s attention to the events at Oka, where Mohawk Indians had laid siege to a commuter bridge to protest the sale of their sacred lands for the construction of a golf course. The speaker called on the community to see the connections between Karbala and Oka and to send the food gathered at the annual food bank to the besieged Indians.

While the collection and distribution of food is a traditional part of the Muharram observance, the whole issue of giving charity to non-Muslims was controversial. It was addressed several times from the minbar, particularly with regard to the issue of blood donations. A taped telephone message at the center recorded before the julus not only gave the timings for various events but reminded community members to give to the food bank. It assured Muslims that the food would be distributed that year only to Muslims. Following this julus, however, an announcement was made before one of the majalis that a portion of the food would be sent to the Mohawks. This is only one example of the way in which the recollection of Karbala reveals courses of action in the present space and moment. From the Shi‘i perspective, the history of the Ahl al-bayt gives direction to the community in its present Karbala.

| • | • | • |

Conclusion

One night while I sat waiting for the majlis to begin, I overheard a small boy running into the center and shouting to a friend, “Karbala is here. It’s really here; it’s out back.” On one level, he was simply referring to the model of the battlefield outside of the center; but on another level, what he was saying was quite profound: the devotional activities at the center during Muharram indeed seek to re-create Karbala. For this child, a lifetime of participation in the paradigm of Karbala had begun.

The re-creation of Karbala allows Shi‘i Muslims to focus their attention on the necessity of allegiance to the Ahl al-bayt. For them, Karbala resonates as a beacon in what would otherwise be spiritual darkness, challenging all who encounter it. The ethical life of the community is continually measured against the lives of the participants in Karbala. For example, the first page of a pamphlet promoting a plan organized by the community for sponsoring orphans in the name of Hazrat Zainab states:

In the name of the great lady who looked after so many children under so much pressure after the event of Karbala, let us fulfill some of our duties as Muslims by actively helping one particularly needy child to enjoy the basic opportunities of life. As Muslims our struggles must go on. Helping the needy is one of the struggles whose results are satisfying. If we remember, “Every day is Ashura and every place is Karbala,” then we will not forget the needy.

Karbala in this context not only serves as a point of reference for the maintenance of group identity, it is also a continuous call to creative ethical action. The Shi‘i community faces a number of problems common to all religious groups in North America: the impact of secularism, the temptations of materialism, and the often uncaring individualism of a capitalist economy. Majlis functions as a kind of Islamic revival meeting, calling people back to an ethical standard exhibited by Husain and his companions in the battle of Karbala.

Sachedina noted that because the imambargah can convey both cultural tradition and religion, there is always the danger that the former will take precedence over the latter. From his perspective, the imambargah is not a place for sentimental attachment to the customs of “home”: it is, rather, a place for spiritual regeneration. As places for the remembrance of Husain, imambargahs are in some sense “sacred spaces.” But as Sachedina told the community from the minbar in Toronto, there is, in actuality, no such thing as a specifically “sacred space” in Islam. The purpose and intention of Islam is to bring all of human activity into conformity with the Divine Will. If the imambargah becomes the only place where people encounter Karbala, then it fails to serve its purpose.

The imambargah succeeds in its purpose when people leave it having internalized Karbala. Since the imambargah is dedicated to Husain, Sachedina warned that if the community fails to use it in the proper way, then on the Day of Judgment, the very stones of the building will speak to pass judgment on the community. In a sense, “sacred spaces” such as the Ja‘ffari Center are problematic: for the very act of creating a sacred environment carries the risk of thoroughly secularizing the world outside of that space. The real “sacred space” in this interpretation of Shi‘ism is Karbala itself, as it is continually encountered in the hearts and lives of each succeeding generation. This focus on the creation of an inner ethical and spiritual life, fostered above all by devotional assemblies, proves to be a common thread in the religious lives of many of the diaspora communities described in this volume.

Notes

1. The Ja‘ffari Center was originally called the Muhammaddi Islamic Center, but its name was changed to honor the sixth Shi‘i imam, Ja‘far As-Sadiq, thus publicly reflecting the Shi‘i identity of the community. [BACK]

2. This was my second trip to visit this community. I had previously attended Muharram activities in 1982 in preparation for a year of research among Shi‘i Muslims in Karachi, Pakistan. Some thoughts on that previous visit can be found in Schubel 1991. The past eight years have seen a number of important developments in the community, some of which are discussed in this essay. [BACK]

3. I am indebted to Professor Karrar Hussein of Karachi, Pakistan, for this insight. [BACK]

4. The Shi‘i ritual calendar makes special note of these occasions as days of remembrance: the Prophet’s naming of ‘Ali as mawla; the victory at Khaibar under ‘Ali; the Prophet’s meeting with Christians at Najran; Fatima’s confrontation with Abu Bakr over Faydak. [BACK]

5. Although zikr in the form of the repetition of the names of God is usually associated with Sufi devotions, it is also a part of Shi‘i piety. [BACK]

6. Dr. Sachedina is not only a scholar of great renown in his community, but also a professor in the Religious Studies Department at the University of Virginia. He is also a frequent zakir at the Ja‘ffari Center. [BACK]

Works Cited

Geertz, Clifford. 1972. The Interpretation of Cultures. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schubel, Vernon J. 1991.

“The Muharram Majlis: The Role of a Ritual in the Preservation of Shi‘a Identity.”

In Muslim Families in North America, ed. Earle H. Waugh, Sharon McIrvin Abu Laban, and Regula Burckhardt Qureshi. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press.

——————. 1993. Religious Performance in Contemporary Islam: Shi‘i Devotional Rituals in Pakistan. Charleston: University of South Carolina Press.

Turner, Victor. 1974. Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Waugh, Earle H., Sharon McIrvin Abu Laban, and Regula Burckhardt Qureshi, eds. 1991. Muslim Families in North America. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press.