Preferred Citation: Robertson, Jennifer. Native and Newcomer: Making and Remaking a Japanese City. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2m3nb148/

| Native and NewcomerMaking and Remaking a Japanese CityJennifer RobertsonUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1991 The Regents of the University of California |

For beloved Serena

Your funeral pyre is getting cold

but we will keep your words

to chase the serpents coiled around our histories

to dream new mythologies

to light our common fire.

Preferred Citation: Robertson, Jennifer. Native and Newcomer: Making and Remaking a Japanese City. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1991 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2m3nb148/

For beloved Serena

Your funeral pyre is getting cold

but we will keep your words

to chase the serpents coiled around our histories

to dream new mythologies

to light our common fire.

Preface

The following is a brief sketch of the historical periods and institutions referred to in this book. The Edo (or Tokugawa) period, 1603–1868, was distinguished by an agrarian-based social and political order unified under a hereditary succession of generals (shogun) from the Tokugawa clan based in the capital city of Edo, whose ruling power was valorized by a hereditary succession of reigning emperors based in Kyoto. Bakufu was the term for the military government. A Confucian social hierarchy adapted from China divided the population into four unequal classes of people: samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants, in that order. Each class was further bifurcated by a patriarchal sex/gender hierarchy. There were several categories of "nonpeople" as well, including outcastes and itinerants. Out of the vigorous urban commoner culture that developed in the late seventeenth century emerged several fine-art and performingart genres regarded today as "traditional," such as the puppet theatre, kabuki, woodblock printing, and haiku. A policy of seclusion kept the country more or less closed to foreign contact and exchange for 250 years.

Victorious antishogun forces restored the emperor to a ruling position in 1868, marking the beginning of the Meiji period (1868–1912) and social changes summed up by the slogans "civilization and enlightenment" and "rich country, strong army." Agrarianism gave way to industrialization, and the seclusion policy to one of imperialism. Japan's first constitution and elected assembly were informed by European (especially Prussian) government systems. The occupational hierarchy

of the Edo social system was replaced by a class system premised on economic stratification and noble lineage. Strict distinctions between female and male divisions of labor and deportment were codified in the Meiji Civil Code, operative until 1947. Generally speaking, the industrialization, militarization, and imperialism of the Meiji period escalated during the succeeding Taisho (1912–1926) and Showa (1926–1989) periods. Although universal male suffrage was inaugurated in 1925, women did not vote until 1947, when sociopolitical reforms were initiated during the American Occupation (1945–1952) following World War II. The late 1930s and 1940s in particular were marked by the military mobilization of the population and the state's appropriation of the Shinto religion as a national creed. The present constitution, which renounces war and (theoretically) the right to possess military potential, became effective in 1947. The emperor is recognized as a symbol of state; sovereignty rests with the people, and the Diet is the highest organ of the state.

Throughout the book, Japanese names are presented family name first unless the person publishes in English, in which case the given name appears first. All translations from Japanese to English are mine unless otherwise indicated.

Acknowledgments

This book is dedicated to the late N. Serena Tennekoon (28 March 1957-2 January 1989), whose love, mind, elegance, and courage are now and forever a sacred memory. The last stanza of a poem written by Serena in 1987 in memory of a Sri Lankan woman, a feminist activist, appears on the dedication page.

The first incarnation of this ethnography was in the form of a doctoral dissertation (1985), and my first readers were the members of my dissertation committee at Cornell University. Robert J. Smith (Chair) was especially helpful at that time. There are many persons who may not read this book but whose assistance, expertise, and goodwill greatly facilitated its production at various stages. I must thank Hishinuma M., Miura S., Miyazaki H., Oda T., Ogawa S., and Oto S., all of Kodaira; the staff of the Civic Life and Social Education Departments, Kodaira City Hall; the staff of the Kodaira welfare center; the staff of the Kodaira central and branch libraries; the director, staff, and steering committee of the Research Institute for Oriental Cultures, Gakushuin University, Tokyo; and D. Chenail, P. Bryant, S. Bushika, and L. Tolle, faculty secretarial office, Williams College. I am grateful to Keith Brown, Larry Carney, Michael Cooper, Ezoe Midori, Stephanie Jed, Vivien Ng, Otobe Junko, Helen Robertson, Sugiura Noriyuki, and Sunada Toshiko for their assistance and support at various stages of this project. Many thanks to Sheila Levine, Amy Klatzkin, and Dorothy Conway for their editorial expertise, and special thanks to Maria Teresa Koreck for critical feedback.

The fieldwork and archival research making possible this book were facilitated by the following awards: the U.S. Department of Education, Fulbright-Hays Research Abroad award (no. G008300855); the International Doctoral Research Fellowship Program for Japan of the Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned Societies with funds provided by the Ford Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities; the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research award (no. 4492); the Japanese Ministry of Education, Monbusho Scholarship; and Sigma Xi, the Scientific Research Society.

Abbreviations

|

Introduction

Ethnography and Making History

The original title of my book was The Making of Kodaira; Being an Ethnography of a Japanese City's Progress. Its source was Gertrude Stein's ethnographic The Making of Americans; Being a History of a Family's Progress (1925). Stein was a consummate ethnographer; she succeeded in illuminating the "bottom nature" of her subjects and their worlds through the process of "condensation." That is, she scrutinized her subjects until, over time, there emerged for her a repeating pattern to their words and actions. Her literary portraits (e.g., Stein 1959) were condensations of her subjects' repeatings, an ethnographic technique quite the opposite of the "social scientific" process of ideal typing.

Nisbet has likened ideal typing to sculpting. Like sculptors, social scientists, figuratively speaking, chip away at a block of marble in order to expose the Michelangelesque sculpture within. This method involves a priori knowledge of both the presence and the exact form of the idealtype figure trapped inside: "the object, whether structure or personage, [is] stripped, so to speak, of all that is merely superficial and ephemeral, with only what is central and unifying left" (Nisbet 1977, 71). Contrarily, the wholeness of Stein's subjects bespeaks the acquisitive—as opposed to reductive—nature of her mode of portraiture. She did not presume to know beforehand what was superficial and what was cen-

tral. These are arbitrary criteria not isolable in any one individual or group. Those features labeled either "superficial" or "central" exist in a flux of words and actions differently repeated over time and space by individuals or groups. As Stein recounts in "The Gradual Making of The Making of Americans ":

When I was up against the difficulty of putting down the complete conception that I had of an individual, the complete rhythm of a personality that I had gradually acquired by listening seeing feeling and experience, I was faced by the trouble that I had acquired all this knowledge gradually but when I had it I had it completely at one time…. And a great deal of The Making of Americans [sic ] was a struggle…to make a whole present of something that it had taken a great deal of time to find out, but it was a whole there then within me and as such it had to be said (Stein, in Dubrick 1984, 13)

Stein in this passage identifies what I perceive as the salient features of the ethnographic process: it is personal; it requires time and patience, for knowledge and understanding are acquired gradually; and it involves a struggle to convey critically that knowledge and understanding about a pluralistic world in flux through the relatively static medium of (English) words (Dubrick 1984, 93). In a similar vein, Agar has noted that

the dominant rhetoric for the discussion of social research as a general process fits poorly with ethnographic work. The traditional linear model of hypothesis-operationalization-sampling design-data collection-analysis is a powerful one, relevant to many questions that might be asked by one human group of another, but at most it plays only a partial role in ethnographic work. Yet the norm is to translate ethnographic work into this rhetoric when discussions move to a general level. The results are a bit like talking about a computer in cubic yards—you can do it, but somehow it misses the point. (1986, x)

Knowledge of the sociohistorical constructedness of cultural practices does not preclude either understanding and appreciating them or working within their parameters (cf. Bourdieu 1986, 2, 4; Dubrick 1984, 26). This practical knowledge,[1] moreover, is crucial if an ethnographer is to avoid the reifications and spurious homogeneity that ideal typologizing, as a form of objectivism, can promote. Bourdieu, for example, has cautioned that

failing to construct practice other than negatively, objectivism is condemned either to ignore the whole question of the principle underlying the production of the regularities which it then contents itself with recording; or to reify abstractions, by the fallacy of treating the objects constructed by science, whether

"culture", "structures", or "modes of production", as realities endowed with a social efficacy, capable of acting as agents responsible for historical actions or as a power capable of constraining practices; or to save appearances by means of concepts as ambiguous as the notions of the rule or the unconscious, which make it possible to avoid choosing between incompatible theories of practice. (1986, 26–27)

Thus, anthropologists of Japan must recognize that the arbitrary model of "the Japanese" as "homogeneous," "middle class," and, since the mid-1980s, "affluent" is a schema of Japanese and non-Japanese manufacture alike. Many of us try to minimize or avoid the fallacious tendency of forcing Japanese cultural practices into Western analytical categories. But we must also strive to distinguish those practices from the dominant ideology—the "ruling definitions of the 'natural'" (Comaroff 1985, 6)—operating in Japan at different historical moments.

My subject is not City Japan but, rather, Kodaira, a city whose texture is a distinctive composition of particular sociohistorical events, practices, and personages. At the same time, because Kodaira is a Japanese city, its composition is not exceptional or anomalous; elements of its texture derive from larger historical, political, and economic conditions affecting the country as a whole. Nevertheless, as I explain below, I did not select to work in Kodaira because it was representative of the majority of Japanese cities (in the way that, say, the Embrees selected Suye-mura as the ideal village for their "community study" [Smith and Wiswell 1982, xxiv]).

One of the ironies of determining the ideal-typeness (such as the Village Japan-ness) of a place is that a city, town, or village often may be selected as a fieldsite because certain features fit the contours of a stereotype or the requirements of a prevailing theory or research proposal. In other words, the particularity of the stereotype, theory, or research proposal is emphasized over that of a place (the fieldsite) and the experiences of its inhabitants. Although my point is made polemically, the situation described is not untypical and, to some extent, is to be expected. Obviously, anthropologists are influenced in their assumptions and choice of a research project or theoretical approach by the disputatious environment of academia and by larger sociohistorical exigencies.[2] However, because of the (increasingly questioned) convention of objectivity in fieldwork, the influential controversies that animate and color inhabited places sometimes remain unheeded or unacknowledged. Moreover, an ethnography framed in the "ethnographic

present" effectively brackets the sociohistorical agency and agents of those same controversies.[3]

The initial research for this book was informed and shaped by various social forces and discourses intersecting in Kodaira during the two-year period 1983–1985, when I conducted the bulk of my fieldwork.[4] In other words, the reflexivity of my text lies in my acknowledged sensitivity to those forces and discourses, and not in a narrative of my trials and tribulations in the field. What I basically want to show in the following chapters is how a problem was created and dealt with (as opposed to solved) during my period of fieldwork.

This ethnography is, to a large extent, a literary portrait of Kodaira condensed from the various repeatings of a particularly cogent word, or trope, in just as many contexts. That trope is furusato, literally "old village," whose resonances and ramifications on the national and local levels are explored critically in chapter 1. The "making and remaking" of my title refers to ongoing discourses about the place of Kodaira past and present, discourses in which the trope of furusato has figured prominently, in recent times, in mediating the past-present relationship. Verbalized as furusato-zukuri, or "old village"—making, this trope has been activated as one of the main ways in which a sense and popular memory of the past are (re)produced outside of professional history writing. Each chapter of this book elaborates on some aspect of furusato, which, as I argue, has been evoked in the Japanese media and elsewhere—increasingly since the "oil shocks" of the early 1970s and consistently during the 1980s—as the dominant representation of "the Japanese" past and future. This representation is collective without being unitary in its meaning (cf. Corrigan and Sayer 1985, 197). Readers should not assume that furusato-zukuri is some sort of central-government conspiracy to force a return to a totalitarian past. Since I explore the sociohistorical conditions under which furusato acquired its representative power and pervasiveness both in Japan and Kodaira in the following chapters, I will limit my discussion here to my understanding and use of the interrelated terms history, past, and future.

History is both a spatiotemporal process and a social production constituting ways in which the past is continuously organized, represented, reclaimed, reworked, and reproduced as memory, which may be private or public and popular. A crucial focus in this book is on "popular memory," which "exists in its relations to the dominant discourses and not apart from them or by itself" (Bommes and Wright 1982, 255). The study of popular memory

is a necessarily relational study. It has to take in the dominant historical representations in the public field as well as attempts to amplify or generalize subordinated or private experiences…. The study of "popular memory" is concerned with two sets of relations. It is concerned with the relation between dominant memory and oppositional forms across the whole public (including academic) field. It is also concerned with the relation between these public discourses in their contemporary state of play and the more privatized sense of the past which is generated within a lived culture. (Popular Memory Group 1982, 211)

The past is constructed and remade in more ways than the written or literary, and by more people than professional historians. Despite a field of competing and contested representations of the past, certain constructions achieve dominance and centrality while others are marginalized (ibid., 206, 207). In this connection, as I show, not only did furusato emerge in the 1970s as the dominant national representation of "the Japanese" past and future, but a particular representation of furusato, one infused with nostalgia, achieved dominance.

The making of Kodaira today largely is a process of remaking the past and imagining the future—a process of reifying a Kodaira of yesterday to serve as a stable referent of and model for an "authentic" community today and tomorrow. In short, as "images, places, and spaces turn from mnemotechnic aids into topoi they become that which a discourse is about" (Fabian 1983, 111). This business of remaking the past, or making history, is a political, practical project in and for the present, for "the proper object of history is not the past but the past-present relationship" (Popular Memory Group 1982, 240), or rather, I would amend, the past-present-future relationship.

"Making history" also describes (in a Steinian sense) the process of ethnography, just as the past-present-future relationship also characterizes it. Ethnography not only "constantly turns us toward the past," but "our past is present in us as a project, hence as our future. In fact, we would not have a present to look back from at our past if it was not for that constant passage of our experience from past to future. Past ethnography is the present of anthropological discourse inasmuch as it is on the way to become its future" (Fabian 1983, 93; italics in the original). It should become apparent that there are many ethnographers of Kodaira, many makers of history, although this book represents my particular contribution.

Furusato-zukuri is a political project not just because of its recent appropriation by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) as the dynamic

of its domestic platform but, more important, in the sense that it is the means by which a consensual version of the past vis-à-vis the present, and the future vis-à-vis the past, is established. Not all of the current agencies and agents through which the image of furusato is stereotyped are linked to the LDP; some are relatively autonomous, such as the "localist" study groups noted in the following chapters. Finally, the vividness, naturalness, and apparent concreteness of the remade past camouflage the rhetorical strategies used in its construction. One of my aims is to make visible both those strategies and the agencies and agents through which they are deployed.

Kodaira City, Ethnographically

Like Stein in The Making of Americans, I am up against the difficulty of "putting down" the various textures of a city that I have experienced both during my childhood and as an adult and a professional anthropologist. I spent my childhood and early teens in Kodaira, and while reminiscing about those eight years (and another two in nearby Musashino City) facilitated many an interview, my personal past did not directly influence my selection of Kodaira as a fieldsite and home from June 1983 through August 1985. A colleague, Matsumura Mitsuo of the Institute for Areal Studies in Tokyo, suggested that the Musashino region in central Tokyo metropolitan prefecture would be an ideal locus for a historical anthropological study of village-making (mura-zukuri ), the substance of my initial research proposal. That I wound up living in my old neighborhood in Kodaira was determined more by the availability of a suitable apartment than by a nostalgic curiosity about my childhood haunts. As it turned out, I could not have landed in a better place at a better time.

Kodaira City is located approximately in the center of Tokyo metropolitan prefecture. Covering about twenty-one square kilometers and shaped like an arrowhead, the city lies about twenty-six kilometers west of central Tokyo (map 1). In 1940 Kodaira was a chiefly agricultural village of about 8,600 persons; its population increased by over five times that number within twenty-five years because of a tremendous influx of newcomers during the late 1950s and early 1960s. The population has remained stable at roughly 153,000 persons since the late 1970s.

Map 1.

Tokyo metropolitan prefecture. Kodaira City

is blackened in for identification.

(Adapted from the map in Zenkoku shichoson yoran 1989)

Map 2.

Kodaira City. (Based on the version in KK 1983; see map 6 for further details)

Kodaira is bisected into northern and southern halves by Oume Road, which, from a sociohistorical perspective, is the most important road in the city (map 2). It was along Oume Road that the area's initial homesteads were founded in the mid-seventeenth century as part of a massive shinden (land reclamation) program engineered by the Tokugawa bakufu in the early 1700s. The descendants of those pioneering settlers continue to live along Oume Road. Collectively, they constitute (as of 1985) the minority (1 percent) "native" (jimoto, tochikko ) sector of Kodaira, in contradistinction to the majority (99 percent) "newcomer" (ten'nyusha, kodairakko ) sector. "Newcomer," generally speaking, refers to those white-collar and blue-collar individuals and families who settled in Kodaira from the late 1950s onward. As I substantiate in the chapters that follow, antinomy between natives and newcomers—partly expressed as competing appropriations of furusato —provides the dialectic that energizes furusato-zukuri in Kodaira.

The name "Kodaira" was coined in 1889 for the new administrative village (gyosei mura ) created when seven smaller villages—the "Kodaira Seven"—were amalgamated under the auspices of the Meiji government's centralization program. Kodaira was made a town in 1944 and a city in 1962. The oldest of these seven villages, Ogawa-mura, was reclaimed from barren land in the 1650s by its namesake, the farmer Ogawa Kurobei. The other six villages were reclaimed about seventy years later, in the 1720s. Kurobei is now eulogized by city hall as the civic ancestor of all Kodaira residents, who are urged in the local press and other media—in altogether anachronistic terms—to follow

Kurobei's example and usher the city into its "second reclamation" period.

City hall is keen on restoring to the sprawling "bedroom town" (beddotaun ) the harmony and camaraderie that allegedly characterized life and work in the seven original villages. Kodaira's second reclamation was inaugurated in the early 1970s under the rubric of furusato-zukuri. Newcomers in particular are encouraged to adopt a "pioneer spirit," which city hall presumes motivated the first reclamation and settlement over three hundred years ago. The rhetoric encouraging newcomers to regard themselves as locals (jimoto ) is countered by increased efforts on the part of natives to reclaim and maintain a special place for themselves within the suburban city.

In the following chapters, I explore and analyze the various contexts within which antinomy between natives and newcomers and competing appropriations of furusato are manifested. These include settlement patterns, festivals, religious consociations, ritual practices, and neighborhood associations. The order in which I have organized the six chapters is my first step in making visible the rhetorical strategies informing native place—making in Kodaira and Japan today. In this connection, at several points in the book I purposely shift from a formal to a more informal style in order to impart a sense of the flavor of my encounters and experiences in Kodaira.

In chapter 1, I introduce the concept and operations of native place—making (furusator-zukuri ) and discuss the politics of nostalgia operating at the national and local levels.[5] My chief interest is in the ways in which "the Japanese" past and future are reconstructed and appropriated. The title of this chapter, "Nostalgic Praxis," refers to the process of furusato-zukuri as a project that involves remaking the past as the condition for bringing about a social transformation—something that is new. That the "something new" is conceptualized in terms of an "old village" points to the operations of furusato as a dominant trope deployed at the national level by the state to both regulate the imagination of the nation and contain the local.[6] In Kodaira "old village" is equated with a purported historical and affective core of the city, a core made visible as theoretical and material metonyms, from the "authenticity" of a "living history" to thatched-roof farmhouses and festivals.

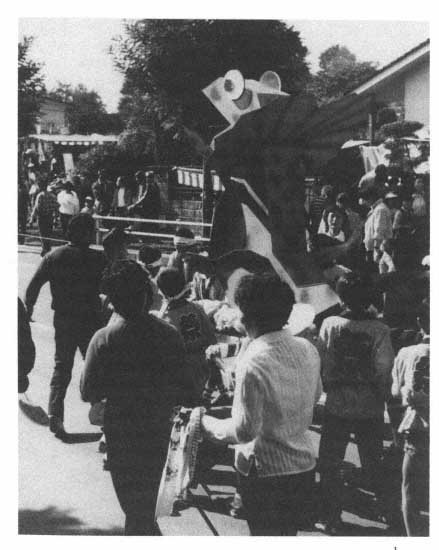

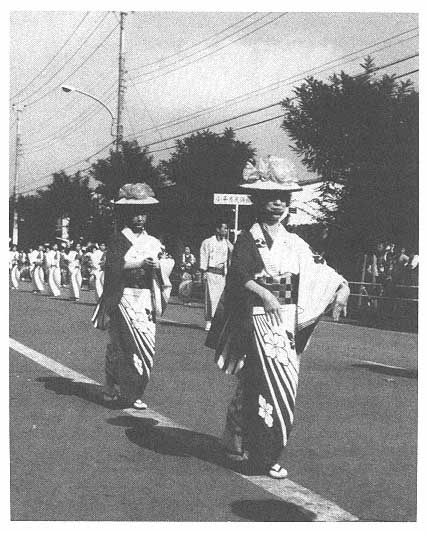

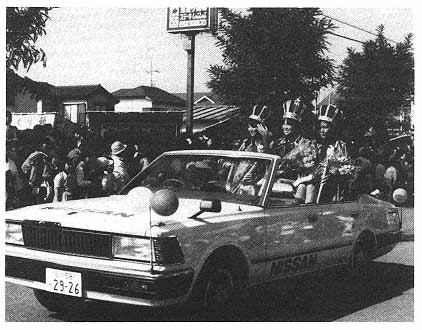

Chapter 2 contains a description and analysis of the Kodaira citizens' festival, inaugurated in 1976 to authenticate the newly reclaimed Furusato Kodaira.[7] Into the terrain of the citizens' festival have been implanted nostalgic interpretations of village life and ritual activities in the

Edo period. It is productive, therefore, to analyze the structure of the citizens' festival in terms of its narrativity. As I elaborate in this chapter, the citizens' festival is both a symbol of Furusato Kodaira and a chronicle, or narrative emplotment, of the past and present social episodes that constitute the gradual making of that city.

Earlier I noted that the proper object of history is not the past but the past-present-future relationship. Significantly, it is under the auspices of furusato-zukuri that Edo-period village life has become an absorbing subject of study in Kodaira and elsewhere. In this connection, chapter 3 has two interrelated agendas. One is to analyze presentday remakings of "Kodaira's" past. The other is to construct from archival data a coherent literary portrait of the social, political, and economic circumstances of the Edo-period farm villages that were later amalgamated under the name "Kodaira." Knowledge of these villages and their settlement illuminates the topographical grounds for the integrity of the native sector. A comparison of the material and symbolic aspects of village-making centuries ago and furusato-zukuri today helps to contextualize the narrative of the citizens' festival.

The authenticating effect of the citizens' festival is achieved by the addition of palanquin shrines (mikoshi ) lent and carried by native residents exclusively. Kodaira natives have sought to reclaim their place in the suburban city largely through religious and ritual channels, the subject of chapter 4. For example, their practice of denying shrine and temple parish membership to newcomers is one of the most explicit ways in which they maintain the integrity of their sector. In this chapter, I extend the twofold agenda of chapter 3 by exploring both the history of religious institutions in Kodaira City today and the conditions influencing the installation of shrines and temples in the newly reclaimed shinden villages. Another dimension of native-newcomer antinomy is provided in chapter 5, in which I explore the various forms of spatial and temporal placement and displacement experienced by natives and newcomers. The very construction and performance of the citizens' festival, moreover, highlight the differential representation of natives and newcomers in terms of their social, geographic, and symbolic place within the city. Neighborhood associations, their historicity and membership, signify another type of settlement pattern in the episodic making of Kodaira. Chapter 6 reviews the furusato-zukuri project, concatenating new examples and ones from the preceding five chapters with the theoretical concepts presented here.

In this book, I explore some of the images and places—such as the

citizens' festival and historical landmarks—that have made the turn from mnemotechnic aids into topoi of discourses on the past-presentfuture relationship. On the whole, I am more interested in the construction of dominant images of and, by extension, dominant discourses about furusato. Public representations of furusato-zukuri —and not private memories of the past, regardless of their collective character—are my concern. Of course, by making problematic the dominant, I simultaneously draw attention to and thereby make visible the marginal. My focus, with respect to Kodaira City, on a dialectic of native and newcomer highlights the forces and relations that sustain the difference between the two sectors and at the same time shows how the newcomer appropriates the native and vice versa.

Chapter One

Nostalgic Praxis

Definitions

"Future society," it has been said, "is the flavor of furusato. "[1]Furusato literally means "old village," but its closer English equivalents are "home" and "native place." Some of the questions raised about "home" might also be asked of furusato:

[W]hat is a home? Is it a place? A set of relationships? A group of possessions? A feeling state? There is no universal answer, nor is there even a simple answer to the question of where a person's home is. Not every person thinks of himself [or herself] as having one, and only one, home. Parents' dwellings and other houses, neighborhoods, towns, or countries may also be thought of as home and even referred to as "my real home."…"Home" may also refer to the roots of one's psychological life which may or may not be the same as one's behavioral life. (Hayward 1975, 8)

Neither "home" nor furusato is simply "an environment where a person's observable life goes on" (ibid.). As a landscape, the quintessential features of furusato include forested mountains, fields cut by a meandering river, and a cluster of thatched-roof farmhouses. Furusato also connotes a desirable lifestyle aesthetic summed up by the term soboku, or artlessness and rustic simplicity. And, as I will discuss, furusato is shaped by, just as it shapes, a "living historical" past. "Living history" has been defined as "the simulation of life in another time" (Jay Anderson, in Handler and Saxton 1988, 242), although at the crux of historical

simulation is the concept of "authenticity" (ibid.). Furusato-zukuri, or "old village"—making (also native place—making), works to integrate present-day activities and interpretations with past events, and to set in motion the construction of an "authentic" image (flavor) of the future.

Furusato is one of the most popular tropes and symbols used by Japanese politicians, city planners, and mass media advertisers and programmers. The ubiquity of furusato derives from the manifold contexts in which it is appropriated, from the gustatorial to the political and economic. In this chapter, I will explore the transformational potential of furusato-zukuri and show how furusato has been deployed as a dominant trope to regulate the imagination of the nation and contain the local.

Since the 1970s, the evocation of furusato has been an increasingly cogent means of fostering insideness at local and national levels alike. Furusato Kodaira, for example, is enveloped by Furusato Japan. The process by which fursato is evoked into existence is furusato-zukuri, a political project through which popular memory is shaped and socially reproduced. The dominant representation of fursato is infused with nostalgia, a dissatisfaction with the present on the grounds of a remembered or imagined past plenitude. Since nostalgia is a barometer of present moods, I will explore the main exigencies occasioning furusato-zukuri.

The Time and Space of Furusato

Furusato comprises both a temporal and a spatial dimension. The temporal dimension is represented by the word furu(i), which signifies pastness, historicity, senescence, and quaintness. Furu(i) also signifies the patina of familiarity and naturalness that objects and human relationships acquire with age, use, and interaction. The spatial dimension is represented by the word sato, which suggests a number of places inhabited by humans: a natal household, a hamlet or village, and the countryside (as opposed to the city). Sato also refers to a selfgoverned, autonomous area and, by extension, to local autonomy.

The written form of furusato also manifests its multivalent nature.

turing the visual (mind's eye) apprehension of furusato —namely, an "old village." The syllables fu-ru-sa-to, however, provide no such extratextual referents but, rather, represent the sound furusato itself as a thing. Furusato today is most frequently written in the cursive syllabary because the word is used in an affective capacity to signify not a particular place—a real "old village," for example—but, rather, the generalized nature of such a place and the warm, nostalgic feelings aroused by its mention and memory.

Moreover, even when the ideographs are used, the current practice is to superimpose syllables above or alongside them, to ensure that the compound is read as furusato instead of as its alternative Chinese-style reading, kokyo.[3] The ideograph, in effect, is divorced from its objective, extratextual referents and is available for use in a connotative capacity. Moreover, as a yamatokotoba, or "really real" Japanese word, furusato, unlike kokyo, appears to be natural, familiar, and culturally relative.

Furusato appropriates a special past: mukashi

The Japanese media are rife with references to furusato: the "flavor of furusato " (furusato no aji ), the "forests of furusato " (furusato no mori ), the "commonsensical wisdom of furusato " (furusato no chie ), and the sobriquet Furusato Japan, to cite but a few. The mass media contribute to and exploit the ubiquity of furusato, and help to make consensual its popular imagination. The landscape depicted in illustrated Tamajiman-brand sake advertisements, for instance, consists of the quintessential features of furusato described earlier. An ode to furusato serves as a caption: "The scenery of the Tama range carries to you a warm smell and the nostalgic song of furusato. This evening, bring on a rush of memories with a cup of our sake. " Such advertisements help

endow rural topography with hallowed content, effectively furthering its sentimental appeal. The appropriation of furusato by sake advertisers is particularly apt, since sake is an indigenous alcoholic beverage made from rice, a crop redolent of nativist symbolism. One ancient nickname for Japan, in fact, is mizuho no kuni (land of fresh rice ears).

Enka, a type of ballad, similarly eulogizes the landscape of nostalgia. These popular songs, enthusiastically crooned at home and in bars by millions of Japanese karaoke (sing-along tape) aficionados, provoke tear-jerking memories of furusato. Lyricists resort most frequently to three categories of furusato symbols in order to facilitate this response. They are symbols of a rural landscape: dirt path, sky, fields, mountains; symbols of estrangement: train, train station, port, train whistle, soldier, letter; and symbols of an "old village" lifestyle: spinning wheel, lullaby, paper lantern, shrine festival (Mita 1980, 220-25). Enka, furthermore, are sung in a nostalgic modality, which involves such conventions as a minor key, slow tempo, wavering melody, and repetitious cadences (cf. Davis 1979, 82–83).

The cogency of furusato, as a sentimentally evoked topography, increases in proportion to the sense of homelessness experienced by Japanese individuals or groups. In this regard, Japanese social scientists—particularly those cited in this chapter—have suggested that, with the rapid urbanization of the countryside since the postwar period, the Japanese "can't go home again." Because of the urbanization of villages, both villages and cities have lost their distinctiveness as social environments—so that the nostalgia provoked by estrangement from an "old village" has become thin and insignificant (Minami 1980, 146). There is no particular place to go home to; consequently, there is no particular place to feel nostalgic toward. Homelessness today may be defined as a "postmodern" condition of existential disaffection: nostalgia for the experience of nostalgia. A diffuse sense of homelessness, then, may be seen as an important sociopsychological motive for the furusato-zukuri project and the symbolic reclamation of the landscape of nostalgia.

The literary critic Kobayashi Hideo (1902–1982) presaged the postwar experience of homelessness in an essay titled "Kokyo o ushinatta bungaku" (Homeless literature, 1933). Paradoxically, Kobayashi attributed his realization of the mnemonic construction of furusato to his own inability to conceptualize "old village" life, a condition he blamed on the fact that he was born and raised in Tokyo (Kobayashi [1933] 1975, 288). He was estranged not from a rural hometown but

from the melancholy experience of estrangement from a rural hometown.

Today at train stations along the Yamanote Line, which encircles the heart of Tokyo, new Furusato Tokyo signs have been posted to direct people to shrines, temples, and historical landmarks in the vicinity. The Furusato Tokyo emblem consists of a red orb, symbol of the Japanese nation-state, across which is superimposed a blue rectangle inscribed in white with Furusato Tokyo. Posters for the 1984 Furusato Tokyo festival, inaugurated in 1981, featured the slogan "Kokoro no naka no Tokyo e satogaeri suru hi" (The day to go home to the Tokyo in [your] heart-mind), reflecting the mnemonic construction of furusato. Unlike the obon (ancestors') festival in late summer and the New Year's festival, two occasions when vast numbers of Tokyo residents return to their natal households, the October event is an occasion for psychic mobility. Residents are encouraged to make a metaphysical return to their new hometown, Furusato Tokyo (Minna no Tokyo, 1 December 1984; see also Furusato Tokyo matsuri jikko iinkai 1986; My Town Concept Consultative Council 1982).

Presenting the Past

Although the imagination of furusato is not constrained by the necessity of a physically present rural landscape, its current reification is shaped by a history of discourse about the countryside. There exists a literary genre of affective environmentalism, beginning in the eighth century with the mytho-histories Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, spanning poetry anthologies and Edo-period farm manuals, and persisting today in the form of domestic policy platforms, city charters, and sake advertisements, among other media and productions.

The confluence of affect and environment is especially evident in the newly revivalized work of Shiga Shigetaka (1863–1927), who identified the mountains, forests, valleys, and streams as the "original forces that nurture the Japanese sense of aesthetics, have nurtured it in the past, and will nurture it in the future" (in Higuchi 1981, 186). Furusato-zukuri, in this context, may be interpreted as a means of reproducing native/national aesthetics in the face of pervasive urbanization and environmental pollution. Shiga, moreover, in his recently republished magnum opus, Nihon fukeiron (Treatise on the Japanese

landscape, 1894), declared that nature is more beautiful in Japan than anywhere else in the world, and even insisted that foreign visitors to Japan were awestruck and humbled by the unparalled beauty of the archipelago. Written during the westernizing Meiji period, Shiga's widely read treanse was an important factor in the development of a national identity predicated on an "[a]ffection for the Japanese countryside and pride in its distinctive beauty" (Pyle 1969, 161) as well as on an awareness of Japan's dramatic emergence in international affairs.

Furusato-zukuri recalls, in spirit if not in substance, early-twentieth-century efforts to achieve a cultural and national identity in a modernizing context; for, as historian Carol Gluck argues, "Japan's modern myths were made in and from the Meiji period" (1985, 16). There are, however, crucial differences between furusato-zukuri today and Meiji-period mythopoeia. Most important is the absence in the furusato-zukuri project of an appeal to the preservation of an agrarian economy. Farmers presently constitute less than 8 percent of the working population, as opposed to an average of 60 percent during the Meiji period, and agricultural production today accounts for less than 4 percent of the GNP (Norinsuisan daijin kankyoku chosaka 1989, 10–11). The general design of furusato-zukuri projects throughout Japan, as I discuss shortly, deals not with an agrarian economy in crisis but with the recreation of a villagelike ambience in cities, towns, and villages alike. Furthermore, the incommensurability between city and country perceived by the Meff ideologues is resolved in the furusato-zukuri project as a dialectic of "tradition" and "modernity," as sobriquets such as Furusato Tokyo and Furusato Kodaira reveal quite literally.

Finally, the sonopsychological catalyst for furusato-zukuri today is a nostalgia for nostalgia. The emperor system, on the other hand, involved an ideology of national unity and identity premised on an agrarian system of born production and social relations (see Gluck 1985, especially chap. 6; also Havens 1974). For this last reason especially, furusato is not isomorphic with the Meiji construct kokutai, the organic national polity. The politics informing the furusato-zukuri project are those belonging to a "postmodern" society, in which "the form of hegemony lies in the power to master signs of styles and periods, the ability to read/construct 'codes of distinction'…order and power do not have to be imposed, or authored, but are already embodied in the very order of objects as they are presented" (Stewart 1988, 232).

Furusato also appears to be a projection of what the ethnologist Origuchi Shinobu (1887–1953) referred to as the "eternal-land cult" of

Yamato, the ancient name for Japan from which yamatokotoba derives. Origuchi suggested that the name Yamato gradually evolved from signifying a "gateway where one enters the mountains" to the land entered through that gateway: "The fact is that the people of old regarded the area within the mountain gateway as being sunny and cheerful…. When one descended through the gateway, one came upon a fertile plain, a bright and happy land. It was generally thought that, once inside the gateway, one encountered no more barriers. Consequently, attention was focused on the gateway itself, and its name, yamato, came to be applied to the land of light and hope within" (in Higuchi 1981, 99).

The generic mountainous landscape now associated with furusato appears to be at once a gateway and the land inside. Current popular memories and interpretations of furusato provide a gateway to further understanding of "the Japanese" landscape of nostalgia.

Popular Memories and Interpretations

At the beginning of 1984, the Asahi shinbun (one of the three leading national dailies) solicited essays for a column on the subject of "new furusato " (atarashii furusato ). (The very appearance of such a column attests to the significance and newsworthiness of furusato.[4] ) The use of "new" suggests that the editors define furusato both in the narrow, literal sense of real "old villages" and in the broader, metaphoric sense of a lifestyle aesthetic premised on a nostalgic interpretation of Edo-period village life. Below are brief synopses of four essays selected for publication in the morning edition of 14 January 1984. Collectively, they indicate the potential of furusato as a basis for the codification of popular memory within the larger political project of furusato-zukuri. By framing the topic of social transformation in terms of furusato, the editors reinforce the dominance of this trope. While my interest here is in the dominant images that emerge in the essays, several individualized and idiosyncratic images are also evident.

First is an account written by a middle-aged woman, a homemaker. She distinguishes between the household's furusato (her husband's natal household) and her own furusato (each of the places where she herself has lived). Her sarariiman ("salary man," i.e., white-collar worker) husband was transferred several times, and so the family has resided in

several cities. Her criterion for a "new furusato " is affective in nature: "When and if a kernel of confidence, trust, and dependency grows between you and your new neighbors, then a new furusato is born." For this woman, affect per se is more central to the re-creation of furusato than is the evocation of a rural landscape, although symbols of an "authentic" community generally derive from the countryside (Gluck 1985, 250).

An unemployed seventy-nine-year-old man, on the other hand, insists that two minimum necessary conditions must be met if a place is either to maintain or to achieve furusato status. They are "motherly love" and a "local dialect." "Without these conditions, he writes, "the furusato -feeling toward a place will evaporate, and regardless of whether it is a residence inherited from one's ancestors, it will float free, remembered only as a faraway place" This essayist recognizes the capacity of language for "generating imagined communities" and building "particular solidarities" (Anderson 1983, 122). His identification of "motherly love" with furusato is also of considerable importance in understanding the sociopsychological valences of furusato in postwar Japanese society, as I elaborate below.

The popular association of "mother" and furusato is so tenacious that social critic Matsumoto Ken'ichi insists that the two words are synonymous. However, because of the rampant urbanization during the postwar period wrought by rapid economic growth, furusato no longer exists as a "concrete entity" (jittai ). Likewise, Matsumoto continues, with the concomitant predominance of urban nuclear families, "mother" no longer symbolizes the countryside (inaka ), the farm village, the land and soil, or rice.[5] Because they have lost their external referents, he concludes, both furusato and "mother" are "dead words" (shigo ) (Matsumoto 1980).

Matsumoto argues that bothfurusato and "mother" have been lost to the same intrusive forces: westernization, industrialization, and urbanization. His point is more fully understood, on one level, in light of amae, psychiatrist Takeo Doi's term to describe a dyadic relationship of mutual dependency modeled after the mother-child manifold, in which one presumes upon another's willing benevolence: the "child" demands to be indulged, the "mother" encourages indulgence (Doi 1986). On another—and, in my view, more cogent—level, Matsumoto's argument is an expression of the nostalgia exacerbated by the so-called "postmodern" malaise.

Insofar as "natal household" is among its various definitions, furu-

sato, by extension, is a place—not necessarily an old village—where one can amae without compunction. Both the elderly essayist and Matsumoto would have it that, as a place suffused with "motherly love," furusato cannot exist without "mother." Their interpretation of furusato can be explained in part by the following argument. Today in Japan, mothers (who are married, as opposed to single) overwhelmingly are perceived as the irreplaceable primary agents of their children's enculturation. But since 1984, nearly 60 percent of the 60 percent of women between thirty-five and fifty-four in the work force are married women, and the majority of these women are very likely mothers (Atsumi 1988, 54–55). This trend evidently disturbs many men and a few women,[6] including the proponents of furusato-zukuri, such as government and civic leaders. The strong connection made in the furusato rhetoric between "motherly love" and amae suggests that what most disturbs these people is the possibility that a "woman with an identity outside the family would not be compelled to find her self-worth only through the successes of her children; accordingly, a strong psychological impetus to induce amae in them would be lost" (Mitchell 1977, 78).

Accordingly, the furusato-zukuri project calls for the realignment of the female sex and the "female" gender role of the "good wife, wise mother," a twofold gender role invented by the patriarchal Meiji Home Ministry (Nolte and Hastings 1991; Koyama 1982; Mitsuda 1985).[7] Significantly, in Kodaira and elsewhere, home-based mothers are encouraged to collect local folktales and read them to their children, ostensibly raising the furusato consciousness of both parties (see Sakada 1984c, 300–302). Exponents of "old village"—making thus are keen on reviving and maintaining the synonymy of "mother" and furusato in the face of urbanization and, more recently, internationalization.

"Mother" names a gender role, a semantic construct unconstrained by the experiences (parturient or otherwise) of real females, who, moreover, are not all " female" in the same way. By declaring furusato and "mother" to be dead words, Matsumoto both unwittingly and ironically confirms the absence of external (physical and real-life) referents for these terms—although the nostalgic implication is that there once were such unified referents. The imagination of both furusato and "mother" is independent of the existence or absence of either; both constructs gain cogency from the process of privileging nostalgia and ideology over historical and experiential reality. Matsumoto blames human agency in the guise of westernization and urbanization) for the death of furusato and "mother," but he fails to acknowledge the human

agency responsible for the construction of these "dead words" and their referents in the first place.

Furusato-zukuri projects are premised on a nostalgia for an "authentic" community symbolized by ofukuro-san, one of the most affective expressions for "mother" used by males and evoked in a wide variety of sentimental media—enka (ballads), for example. Ofukuro-san literally means "bag lady" and, consequently, refers connotatively to the notion of females as repositories—in this case, repositories of "traditional" values deposited for safekeeping by the (male) engineers of furusato-zukuri programs. This term for "mother" is a telling throwback to the premodern reference to females as ohara-san, or "womb ladies," indicative of a belief in procreation as a monogenetic phenomenon, or the belief that the male sex role is the generative and creative one and that the male alone is responsible for the identity and subjectivity of a child. Female bodies, literally and figuratively, are the containers for male-identified "babies," from human infants to things such as values and ideologies.

When Matsumoto and others attribute the death of "mother" to westernization and urbanization, they are—in effect—alluding to the crumbling of male certainty about the virility of "traditional" values and providing a chauvinist incentive for cultural monogenesis (see Mattelart 1986). Although the same "traditional" values were eschewed in the immediate postwar period as backward, cumbersome, and encumbering, they are now being implanted into the landscape of nostalgia, the isomorph of which is the female body qua "mother," where they can be cultivated (gestated) and harvested (delivered). An ideology of sexual difference and gender-role segregation informs the image of a "back-to-the-future" old village redolent of "motherly love." By conflating furusato and "mother," nostalgic men—like Matsumoto, politicians, and the Kodaira City administrators—can proclaim the inclusion of precisely what is excluded from the cure for the "postmodern" malaise—namely, female-identified subjectivity and self-representation. Such men may be nostalgic for the Good Old Days, but they remain very much a part of the present.

A third contributor to the column on "new furusato, " a housewife, identifies progress as the juggernaut that has crushed the élan of furusato. Her account is a personal one. She is discouraged by, but somewhat resigned to, the consequences of urbanization, to which furusato is all too vulnerable. The jarring image she evokes is one of rice paddies overlaid with concrete highways. She recognizes, however, that

people (in this case farmers) themselves ultimately are to blame, for their desire to profit from land sales only hastens urbanization (regardless of their concrete socioeconomic motives for giving up the hoe).

A final essay was submitted by a middle-aged man, a civil servant. He wonders whether the "my town" planned communities presently under development throughout Japan can ever be realized as "new furusato. " Placing furusato within a rural setting, he argues that "campestral features such as nostalgia, pleasant scenery, compassion, and camaraderie cannot simply be reassembled and called furusato. " His conditions for an "authentic new furusato " are presented as desirables and imperatives. He insists that

furusato should be a place where one can return whenever the urge strikes. And, ideally, it is a place where one's kokoro [heart-mind, conscience] finds repose and where daily-life routines are grounded in compassion. Second, it should be a place where customs and traditions are highly valued. The history of a town or village should be transmitted through story from generation to generation, and this in turn should be the source nurturing familistic ties and a feeling of regional solidarity. Third, an authentic furusato is not likely to be realized on the basis of an academic blueprint implemented by government offices. Residents themselves must determine self-consciously just what is furusato.

Ironically, and perhaps because he is a civil servant, this last essayist's criteria of and for a "new furusato " are virtually identical to those recommended by central-and local-government, and civilian, proponents of furusato-zukuri projects. Also evident here is an appeal to self-government or local autonomy (jichi ), and the notion of the rural village, along with the "good wife, wise mother," as repositories of authentic and authenticating social values.

Furusato-zukuri projects are often categorized under the epochal rubric chiho no jidai, or "age of localism." Since the late 1970s, when the expression was coined, a vociferous debate has been waged as to whether "age of localism" euphemistically disguised the collapse of local autonomy or marked a departure from and a viable alternative to Tokyo-centrism (see Yamaguchi 1981). For instance, Isomura Eiichi, chair of the Japan Urban Studies Association, contends that chiho no jidai actually names an "age of cities." That is, the slogan reflects a move on the part of regional cities to emerge from the shadow cast by Tokyo and assert their "unique" characteristics (Isomura 1981, 16, 208). While this is not the place for an extended discussion on the vicissitudes of local autonomy in Japan,[8] it is pertinent to note that, in the Meiji period as in the present examples, chiho was variously defined as the

"opposite of cities" and/or any place outside Tokyo. Moreover, like furusato today, jichi in the early twentieth century possessed a double meaning: it emphasized localities' administrative self-governance and at the same time "tied the chiho as closely as possible to the center" (Gluck 1985,193).

All but one of the above essayists equate furusato with a nonurban setting, and key furusato components—nostalgia, pleasant scenery, local dialect, compassion, camaraderie, motherly love, enriching lifestyle—are described as qualities endemic to the countryside. The remaining essayist does suggest that furusato and city are compatible, insofar as neighborly trust and dependency are the foundation for a "new furusato. " All but the first essayist, however, suggest that "new furusato " evokes the affective relationships and sociabilities presumed to have mediated and moderated life in "old villages."

Another perspective on the subject of "new furusato " is provided by a survey conducted in October 1985 by the newly established (May 1985) Furusato Information Center in Tokyo. The center was founded under the auspices of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries to facilitate the rehabilitation of depopulated rural communities through the creation of city-country networks.[9] Its operating budget for 1985 was about 450 million yen, part of which was spent networking with over 1,700 cities, towns, and villages; sponsoring symposia; installing a furusato information "hot line"; distributing pamphlets, newsletters, and guidebooks; and conducting a survey on furusato, its image and efficacy (Furusato joho senta-dayori, 1986; Nakajima 1986).[10]

Part of the center's survey required the 1,920 female and male respondents to offer words they associated with furusato. Inaka (countryside) overwhelmingly was the respondents' first choice, followed by shizen (nature), yama (mountains), and kawa (rivers). More than public opinion per se, these results seem to reflect the generic image of furusato popularized in a variety of mass media and adopted by consumers. Other furusato synonyms included atatakai (warm, intimate), shusshinchi (birthplace), ryoshin (parents), haha ([my] mother), soboku (naive, pristine, simple), and kokoro ga yasumavru tokoro (place where the heart-mind finds solace), in that order (Furusato joho senta 1986, 16–17, 48).

The language of the "new furusato " essays and the center's survey strongly suggest that old village-ness is signified through antithesis. Furusato is not limited to an actual rural place, nor does it presuppose

an agricultural lifestyle. It is, rather, everything that suburbs and metropoles are not. Compassion, camaraderie, tradition, and even motherly love are presumed absent from postwar urbanized society, with its preponderance of nuclear families and mothers working for wages outside their homes. Nearly half of all Japanese live within fifty kilometers of the three largest cities (Nagoya, Osaka, Tokyo), on 1 percent of the land, and over 75 percent live in urbanized areas. For them, the image of an old village offers an appealing alternative to overcrowded, impersonal living conditions. Moreover, unlike the Edo-period farm village, with its harsh system of sanctions (such as murahachibu, or ostracism), the "new furusato " is represented as a benevolent community emerging from the nostalgic imagination of "homeless" Japanese. The grand design of the "new furusato " programs in suburban cities throughout Japan is the creation of a villagelike ambience (see Sakada 1984b, 1984d; Tamura and Mori 1985). Recognizing that native place-making mostly is a matter of reclaiming mental and cultural terrain, proponents of furusato-zukuri aim to cultivate and harvest that terrain, or the landscape of nostalgia.

The Landscape of Nostalgia

In his treatise Bungaku ni okeru genfukei (Original landscapes in literature), Okuno Takeo offers a nativist explanation as to why "old village" is such a ready model of and for cultural renewal. The Japanese, he claims, are historically a farming people; therefore, despite a century of industrialization and urban growth, they "are subconsciously and collectively imprinted with the image of farm (paddy) villages and their environs" (Okuno 1975, 72). Since furusato is, according to Okuno, an Ur -landscape permanently etched on the kokoro of ethnic Japanese, it can be evoked through the agency of nostalgia. Okuno's ideas illustrate effectively the cultural mythopoeia and appeal to popular memory informing furusato-zukuri.

Nostalgia figures as a distinctive way of relating the past to the present and future by juxtaposing the "uncertainties and anxieties of the present with presumed verities and comforts of the…past" (Davis 1979, 10). Nostalgia is not a product of the past, for what occasions it resides in the present, regardless of the sustenance provided by memories of the past.

To refer to the past, to take account of or interpret it, implies that one is located in the present, that one is distanced or apart from the object reconstructed. In sum, the relationship of prior to present representations is symbolically mediated, not naturally given; it encompasses both continuity and discontinuity. (Handler and Linnekin 1984, 287)

Nostalgia is provoked by a dissatisfaction with the present on the grounds of a remembered or imagined past plenitude. The proponents of furusato-zukuri acknowledge the newness of the old, as evinced by the oxymoronic term "new furusato. " The prefix furusato is used to identify and distinguish things purportedly indigenous to Japan. But the sobriquet Furusato Japan also attests to the ruling Liberal Democratic Party's (LDP) recent appropriation of furusato-zukuri as an administrative model of and for a "new" national culture.

Furusato-zukuri was adopted in 1984 by the LDP as the affective cornerstone of domestic cultural policy. The new policy, referred to as "Nippon retto furusato ron" (Proposal for Furusato Japan), was introduced that year in a televised speech by the finance minister, Takeshita Noboru. In 1987 Takeshita succeeded Nakasone Yasuhiro as prime minister, and appropriated furusato as the trope for his own political platform. Although he resigned in 1989 following charges of corruption, Takeshita's brainchild, the Furusato kon no kai (Spirit of Furusato Association), was adopted by the present (1989) prime minister, Kaifu Toshiki, as his personal advisory committee.[11] Political factionalism aside, the LDP as a whole regards furusato-zukuri as the means by which to forge a new "cultural state" (bunka kokka ) in tandem with a "new Japanese-style welfare state" ("Nihonsei no atarashii fukushi kokka") (Takeshita and Kusayanagi 1986, 10; see also Showa 59-nen to undo hoshin 1984).

Tanaka Kakuei, the former (and now incapacitated) prime minister, spearheaded LDP interest in furusato-zukuri with his 1973 bestseller, Nippon retto kaizo ron (Proposal for remodeling Japan). Takeshita simply replaced "remodeling" withfurusato in appropriating his former mentor's title. In his book, Tanaka bemoaned the fact that "for an increasing number of people, furusato is but a small apartment in the city," and worried that "the present state of affairs will make it difficult for the Japanese people to transmit their superior qualities and wisdom to the next generation." His proposed program of decentralizing industries and increasing transportation networks was aimed at creating "what the Japanese people want most…a beautiful, livable land and an untroubled future" (Tanaka 1973, i–ii). Tanaka's proposal—already under-

mined by the disclosure that his associates had been informed of details which enabled them to speculate in local real estate—was rendered economically moribund by the "oil shocks" of the early 1970s.

Where Tanaka had focused on remodeling the physical landscape, the LDP seems to be interested in exploiting the affective potential of furusato-zukuri toward the creation of a politically symbolic landscape of nostalgia. The adoption of the term furusato signals the reorientation of domestic policy from a preoccupation with strictly material needs to a preoccupation with the affective dimensions of materialistic wellbeing. This shift is evident in the savings bonds advertisements discussed shortly. Its folkish, nostalgic connotations imbue the furusato-zukuri project with an emotional appeal and a legitimacy sanctioned by "tradition." But, as I discuss later in the context of advertising, the "tradition" evoked by furusato does not depend on an objective relation to either the past or the countryside.

As something perceived as broadly "Japanese," furusato appeals to a wide spectrum of political interests, from the right to the left. The postwar revaluation of local practices was promoted from the early 1950s by localists and "antigovernment" forces,[12] although the favored expression then for "authentic" community was not furusato but kyodotai, a concept I discuss at length in chapter 3 (Irokawa 1978). Today furusato is evoked both by local environmentalist groups, who are opposed to chemical fertilizers and pesticides,[13] and by the conservative LDP. Actually, the LDP adopted furusato only after its rhetorical and symbolic usefulness had been established by local and regional agencies. The promotion of furusato-zukuri offers the party an efficacious way of addressing troublesome political, social, and environmental issues under a single rubric.

Public opinion polls conducted over the past decade by the prime minister's office and private agencies reveal that the respondents harbor pessimistic views about the future of their society. Rural depopulation and environmental pollution are seen as especially worrisome and are associated with high economic growth. The central government regards such views as the consensus of popular opinion. In a poll published in February 1984, six months before Takeshita's "Proposal for Furusato Japan," 50 percent of the respondents felt that Japanese society would become more hectic and unstable in the future. The results were used in formulating the Fourth Comprehensive National Development Plan now in effect (Japan Times, 5 February 1984; YanoTsuneta Kinenkai 1985, 35, 313-17). In response to the worries

expressed in such opinion polls, the Association of National Trust Movements in Japan was founded in 1983. The objective of the association is to prevent the "destruction of environments of scenic or historic value through indiscriminate development or urbanization" (Kihara 1986, 190). In conjunction with the aims of furusato-zukuri, the preservation of historical landmarks and nostalgic landscapes also constitutes an effort to reinvent a "traditional" style of social relations.

Japanese political and social commentators (hyoronka ) tend to attribute the current preoccupation with furusato to the oil shocks of the early 1970s. "Oil shocks" is a now clichéd expression for the reactions of Japanese people to the dramatic rise in the cost of petroleum. It is argued that this development reminded them—or, rather, was used to remind them—of their chronic dependence upon imported raw materials, and led to a revaluation of "tradition" with a view to attaining self-sufficiency.

Self-sufficiency in the context of furusato-zukuri, however, actually embodies less an effort after political and economic independence than the pursuit of an "authentic" community in contradistinction to internationalization. As Befu has discerned, "the very processes of Japan's internationalization induce its separateness from the rest of the world and cause Japan to assert its cultural autonomy" (1983, 261). Sociologist Isamu Kurita agrees, and has argued that the search for an "Exotic Japan" by Japanese today was stimulated by the internationalization of postwar culture:

[T]he very international-ness of the life-style makes the traditional Japanese arts appear quite alien and exotic. We look at our tradition the way a foreigner does, and we are beginning to love it. It is the product of a search for something more "advanced" and more modish than what we have found in our century-long quest for a new culture.[14] (1983, 131)

What the oil shocks signaled was the end of high growth produced by the "economic miracle" of the 1960s. High growth itself could no longer be regarded as a political panacea, and political confrontation with the sociocultural costs of rapid economic growth could no longer be postponed. The end of the "economic miracle" meant the end of big spending programs, such as free medical care for the elderly and welfare support for children and disabled people. Furthermore, the crisis precipitated the decline of progressive politics and the concomitant strengthening of conservative (LDP) influence. The LDP has since co-opted the formerly progressive issues of pollution, welfare, and citizen par-

ticipation (Samuels 1983, 214-19; Showa 59-nen to undo hoshin 1984).

The nostalgic experience is particularly intense where the sense of vexation and insecurity is not just limited to the present but is expected to color the future as well (Zwingmann 1959, 199). Since nostalgia is a barometer of present moods, the ubiquity of furusato would seem to bespeak a chronic, pervasive anxiety on the part of many Japanese people today. Anthropologist Mitsusada Fukasaku echoes this anxious sentiment with his remark that the Japanese "can't go home again." He argues that

traditional patterns of life and thought are no longer possible, because Japan is no longer geographically isolated from the international community, [because] agriculture is no longer the basis for the Japanese economy, because Japan's once beautiful nature has been destroyed by pollution and urbanization, and because the traditional culture has been completely commercialized. (in Wagatsuma 1975, 330)

Although Fukasaku insists that the people of Japan will begin to create "a new culture of their own," he does not venture any suggestions about the form and content of this "new" entity. The "new" culture—the "authentic" community—appears as a state-regulated project in which the nostalgia for nostalgia is manipulated, on the one hand, to mask human responsibility for socioecological change and, on the other, to create a collectivist mythopoeia predicated on the reification of the "old village." "Old villages" are presumed to have existed in harmonious tranquility until vitiated and transmogrified by outside forces—such as westernization, industrialization, and urbanization. In the furusato-zukuri literature, change for the worse is described as precipitated by external agents. Change for the better, on the other hand, is presented as a wholly Japanese undertaking, a rallying against intrusive foreign agents. This distinction is evident in the verbs used to denote change. Change for the worse is denoted by passive expressions containing the intransitive verb naru (to evolve, to become, to be). Naru brackets, deflects, and conceals intentionality: creation is presented as an irruption, an epiphany, a release of what already is there.

Naru contrasts with tsukuru (to make, to build), a transitive verb that denotes intentional, purposeful action. Tsukuru is linked with furusato to form the compound furusato-zukuri. Unlike naru, tsukuru acknowledges that creation is a form of labor, a conscious construction. Naru elides or renders unproblematic the sociohistorical conditions of

production; things simply enter the realm of present actuality from somewhere in the past. Thus, when the administrators of Kodaira bemoan urban sprawl, they couch their complaints in naru expressions: Kodaira "has become" a sprawling bedroom town lacking integrity. In this way, the administrators can avoid blaming specific persons and groups for the city's problems and instead exhort residents "to actively make" Kodaira into a place "we can call furusato. " Similar rhetoric and a preponderance of -zukuri compounds characterize the LDP's 1984 platform.[15]

"Old Village" Villages

As a local-level policy, furusato-zukuri is not limited to cities faced with the untoward consequences of urban sprawl. It is also implemented in rural villages as a strategy to check depopulation. The term furusato-mura ("old village" villages) designates depopulated villages seeking to attract "honorary villagers." Honorary villagers are long-term tourists from the city who can enjoy picking mushrooms and bracken, slopping hogs, and transplanting rice seedlings without having to actually depend on agriculture for a living. Neither do the native villagers, since tourism is regarded as a more lucrative and desirable enterprise.

The Furusato Information Center functions as a clearinghouse for both prospective furusato-mura and honorary villagers. An example of typical copy prepared by a "village" for perusal by urban clients and publicized by the center is translated below. The site in question was newly renamed Kozuke-mura, after the pre-Meiji name for the area now encompassed by Gunma prefecture. This profile recalls Origuchi's discourse on Yamato as a gateway.

Pursue the romance of "Kozuke-mura, " Gunma's secret frontier (gateway). The pristine currents of the "Kannagawa" flow through the center of the village, which is encircled by mountains. Ninety-four percent of the land abounds in beautiful forests—which is why it is called "Gunma's secret frontier." Kozuke-mura has a history spanning more than 200 years: the Kurozawa family house was designated a national treasure…. Petrified rocks impart the romance of the Age of Dinosaurs. Many natural monuments—national and prefectural treasures—are found here.

Moreover, traditional seasonal events… and folk arts… are still passed on from generation to generation in their original form.

Natural wonders and pure traditions have been preserved in their original state. Those things unnurtured in a city, like a "restful heart-mind" and "poetic sentiment," are reawakened here. (in Nakajima 1986, 105)

Most of the so-called traditional village activities performed in furusato villages are either recently invented or newly revived as recreation for domestic tourists. Among them are festivals, kagura (Shinto music and dancing), folk kabuki, storytelling and folksinging sessions, handicrafts exhibitions, nature hikes, and rice-pounding contests. Honorary villagers, who pay an average annual residency fee of about 10,000 yen, enjoy other amenities as well. Back "home" in the city, they are provided with furusato newsletters and local produce (Asahi shinbun, 13 March 1983; Furusato joho senta 1985; Kawashima 1984, 121-26; Sakada 1984a, 353–419). Real villagers, on the other hand, are entrusted with the custody of an irreplaceable (if imagined) community; they are curators of the landscape of nostalgia.

For natives and honorary villagers alike, what is experienced is not village life but a villagelike life. Honorary villagers are encouraged to think of a given village as if it were indeed their "new furusato." This "as if" does not denote falsity but, rather, refers to an imagined community. It is not false, because it is "a part of social relations which has a definite effect. In living 'as if,' subjects do not live in illusion, this 'as if' is the reality of their existence as subjects" (Paul Hirst, in Strawbridge 1982, 132).

Furusato-mura provide access to another, more "authentic" future society, but the "old village" villages must also be sufficiently of this world to be accessible by public or private transportation. Japan National Railways (JNR, privatized in 1987 as Japan Railways) early recognized its potential to traverse past and present. From "Discover Japan" in the 1970s to "Exotic Japan" in the 1980s, JNR advertised its worldbridging services to "homeless" urbanites. In the Meiji period, "agrarian moralists" warned of the detrimental effect trains would have on rural life (Gluck 1985, 163). Today the railroad brings people back to both the countryside and a nostalgic frame of mind. What is ironic in this connection is that, whereas rail service to isolated rural stations is being phased out gradually, nostalgia-evoking steam engines are making newly scheduled runs as tourist attractions. Those who are unable to travel can take advantage of the post office's "furusato parcel post" (furusato kozutsumi ) service, inaugurated in 1985. Customers can choose from a variety of regional foodstuffs and handicrafts, colorfully advertised in "furusato parcel post" catalogues. The parcels are then

posted directly to them from local manufacturers. Domestic tourism is a cogent means of inducing nostalgia and occasioning the experience of an exoticized past. Railway companies, the post office, and developers of furusato-mura alike recognize that leisure, just now becoming an industry in its own right in Japan, is among other things an anodyne realm in which gratification is offered in compensation for the disturbing consequences of postwar urbanization.

Conclusion: The Making of Furusato Japan

Furusato-zukuri is employed by the state as a synonym for "cultural administration" (bunka gyosei ), which in turn signifies the reorientation of domestic policy since the "oil shocks" of the 1970s from a strictly materialist to a more affective focus. The present time is referred to in various media as an "age of affect" (kokoro no jidai ), the rather premature rationale being that, since basic material needs have been more or less met, civil servants and city planners must attend to the emotional needs of the people (cf. Uruoi no aru machi-zukuri kenkyukai 1984, 21–22). This slogan is illustrative of the symbolic and affective political context within which furusato ideology operates. Former Prime Minister Nakasone consistently expressed the need for "heart-mind accord" (kokoro no fureai ) between political administrators and the people (e.g., Nakasone 1984). Nakasone's call for administrative reform was characterized as the "culturization of administration" (gyosei no bunkaka ), the complement of "cultural administration" (Aiba et al. 1985, 296–319; Ando 1984, 143-54; Mori 1985, 49–62).[16]

The "culturalization of administration" involves transforming the essential substance and nature of administration itself: decorating government offices with works of art; producing colorful pamphlets that explain administrative policy in jargon-free language accessible to the public; making government buildings available on weekends for public use, such as for hobby classes; broadcasting music from government buildings during holidays, to create a festive ambience; and nurturing affective relations between civil servants by promoting the use, in their memos, of the more warmly respectful suffix sama over the indifferent dono (Mori 1985, 56; see also Tamura 1985, 3–20, 52–61).

Implicit in the "culturization of administration" is the idea of admin-

istrating culture and "tradition." Both are evoked to signify and provoke a new "value consciousness" (kachi ishiki ) informing the furusato-zukuri project. Planners, bureaucrats, advertisers, and the polled public seem to recognize implicitly that "traditional" aspects of culture and social life do not constitute an objectively definable inheritance, although they may be eulogized as such. Instead, they are negotiable symbolic constructs continuously reinvented in the present—and, in the case of furusato, through the agency of nostalgia.