Chapter 4

Castle on the Plains

New Relationships

The construction of Bent's Old Fort cast the beliefs and values of the modern world into material form. It became a kind of "medicine lodge" for the ritual behaviors—and the material symbols associated with these rituals—that served to established the new ideology in the Southwest. We can see in Bent's Old Fort the "calcified ritual" of Yi-Fu Tuan and in the history of the fort the results of that ritual. One result was the very definite class hierarchy that arose with the construction of the fort: company owners at the top, other free traders next, then trappers, then Mexican laborers, and, at the bottom, the Native Americans. Among the Native Americans, though, the Cheyenne and the Arapaho held by far the highest status, evidenced in part by the fact that they were sometimes admitted inside the fort. Other Native Americans were never permitted inside the boundaries of the fort's walls. The fort served as a "model," if you will, of the new systems of control introduced by the Anglos, but it also functioned to implement those controls. It provided a paradigm for what amounted to the industrialization of the southwestern Plains and, later, of the Southwest.

But the fort was not introduced into a cultural vacuum. Native American and Mexican groups protected and advanced their interests in strategic ways. A visitor to the Southwest today can see what was accomplished by their maneuvering: a modern society that displays a unique combination of Hispanic, Native American, and Anglo cultural traits. It is also a society in which dialogue among groups of different cultural backgrounds and resistance to cultural homogenization commonly occur.

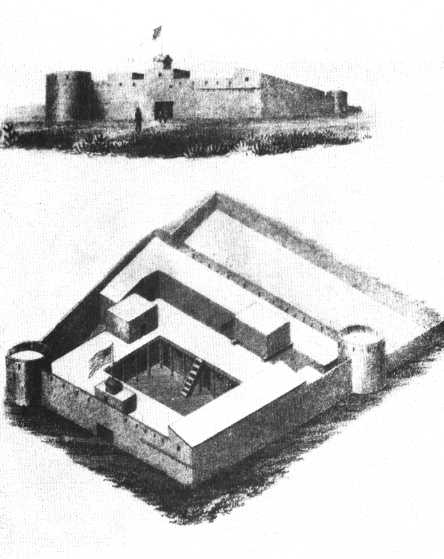

Figure 8.

Bent’s Fort, as drawn by Lieutenant J. W. Abert in his

“Journal from Bent’s Fort to St. Louis in 1845." (Courtesy

Colorado Historical Society, Denver, file #26318;

Senate Doc. 438,29th Cong. 1st sess.)

Bent & St. Vrain Company

Bent's Old Fort was by far the most impressive of several structures built by the Bent & St. Vrain Company, a partnership formed by Charles and William Bent and Ceran St. Vrain. This partnership is first evidenced by a letter dated January 6, 1831, from Ceran St. Vrain to Bernard Pratte & Co., so it seems likely that the company was formed a bit earlier, probably in 1830[1] Later, Bent brothers, George and Robert, became involved with the company and lived for some time at Bent's Old Fort and the other forts owned by the company. They, however, played relatively minor roles in the general management of the company.

The company had been created to exploit the commercial opportunities offered by Mexican Independence in 1821. Beckoning American traders and trappers were the silver bullion and furs of Santa Fe and Taos, beaver pelts from the almost untrapped streams south of the Arkansas River, and the buffalo hide trade with the nomadic Native American tribes in the vicinity, of the Arkansas and Platte rivers. New Mexico had been jealously guarded from the attentions of Americans until that time by the Spanish. Native American groups who were trading with the Spanish also had harassed American traders and trappers in the area north of New Mexico prior to Mexican Independence in order to protect their position in that trade.

There is some evidence that the Bent brothers had constructed a stockade at the eventual site of Bent's Old Fort as early as 1828.[2] By that time the Bents were actively trading on the Arkansas River. The construction of Bent's Old Fort from adobe bricks may have begun at that same time or a few years later. Janet LeCompte, a historian who has specialized in the upper Arkansas River Valley, has argued that work did not begin on the adobe fort before 1833,[3] although archaeological evidence indicates a

beginning date of construction of about 1831.[4] Construction seems to have been interrupted by a smallpox epidemic which scarred William Bent for life.[5] A letter written by Ceran St. Vrain to the U.S. Army dated July 21, 1847, attempting to interest the federal government in the property, stated that the fort "was established in 1834," but this was written some years after the fact;[6] the fort was probably ready for business by 1833.[7]

By the time the fort was completed, the Bent & St. Vrain Company was already enjoying truly remarkable financial success. In early November of 1832 the company wagon train arrived in Independence, Missouri, with a cargo valued at $190,000 to $200,000. The silver bullion, mules, and furs had been gathered together over the course of two years.[8]

The massive adobe trading post was known as Bent's Fort and Fort William while it was occupied. It became "Bent's Old Fort" after its abandonment in 1849 and the construction by William Bent of another trading post in 1853 at Big Timbers. William Bent was the sole proprietor of this smaller post, built of lumber and stone. It soon became known as Bent's New Fort. William operated his new fort until 1860, after which he continued to trade from his ranch on the Purgatory River until his death in 1869.

The company of Bent & St. Vrain was dissolved in 1849, the year of the old fort's abandonment, a victim of rapidly changing and sometimes tragic circumstances and the inability of the company's leadership to cope with this. Charles Bent, after being appointed the first American governor of New Mexico, was murdered in Taos in 1847 by an angry. mob incited by the outgoing Mexicans. Company leadership became impaired with his death, not only because of the loss of Charles's business acumen and influence but also because of the emotional reaction suffered by the surviving partners. William Bent's anger and frustration at the loss of his brother, compounded by other personal difficulties he was experiencing, may have influenced his decision to abandon Bent's Old Fort. Indications that he tried to destroy the fort as he left support this speculation. But it was Ceran St. Vrain who acted to dissolve the company. Facing up to the general unrest after the Mexican War among the Native American tribes and the changing world market for furs, as well as the death of Charles Bent, the canny St. Vrain probably decided that other ventures held more promise.

Position, Strategy, and Execution

Bent & St. Vrain Company owed its considerable success to the ability of the principals to understand, and to skillfully operate within, the emerging capitalistic world market and the Native American trading systems. The fort was essential to the company's strategy.

Whereas other entrepreneurs had deployed their own trappers or had attended Native American trading rendezvous, Bent and St. Vrain saw that operating from fixed trading posts would be a superior strategy in the trading environment of the southwestern Plains in the early 1830s. Buffalo hides were supplanting beaver pelts as the most desirable of furs in the trade. These could be procured solely from the Plains Indians, who

knew not only how to hunt the buffalo but also how to prepare the fur. Various tribes among the Plains Indians, though, militantly protected the positions they had established as middlemen in Native American trade. The fixed trading posts let some of the tribes enhance their position.

Pacifying Native American groups by allowing them an important role in the fur trade permitted Bent & St. Vrain Company to maintain a presence on the international border. New Mexico, with its untrapped rivers and untapped reserves of Mexican silver, horses, mules, and blankets, lay just across the Arkansas River from the fort. The large adobe fort offered an alternate trading locale to the ancient fairs held at Taos and Pecos pueblos and the more recent Spanish and Mexican trade at the cities of Taos and Santa Fe. From the day business began at the fort, the availability of manufactured goods there drew trade from the New Mexican pueblos and cities.

During the height of the favorable market configuration, Bent & St. Vrain Company operated several smaller trading posts on the southwestern Plains in order to maximize their profits (see fig. 9). Intertribal fighting made these posts desirable, since warring Native American groups were cautious about entering territories frequented by their enemies. In 1842, Bent & St. Vrain Company built a log trading post on the south fork of the Canadian River, in what is now the panhandle of Texas. In 1845, they built a more permanent adobe post a few miles from the first. The second post on the Canadian became known as "Adobe Walls" (and was the scene of two famous battles between Anglos and Native Americans after its abandonment). These posts were established to facilitate trade with the Kiowa and Comanche, who were generally loath to venture north of the Arkansas River into the territory, of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, despite the Bent & St. Vrain Company's continuing efforts to make a peace between these tribes.

Earlier, Bent & St. Vrain Company had built a substantial adobe trading post on the South Platte, north of the future site of Denver and twelve miles below what would be called St. Vrain Creek. George Bent, the brother who probably supervised its construction, named it Fort Lookout. Later it would be known as Fort George, and finally as Fort St. Vrain, most likely because by that time Ceran St. Vrain's brother Marcellin was frequently in charge there. Fort St. Vrain was more accessible to some of the bands of Cheyenne and Arapaho who preferred to stay north of the South Platte and to the Ute, Sioux, and Shoshoni. The establishment of the fort, moreover, neutralized attempts by several other traders to establish posts in that vicinity.

Figure 9.

The trading empire of Bent & St. Vrain Company. (Illustration by Steven Patricia.)

Probably for the reason of eliminating competition, Fort Jackson, also on the South Platte, was purchased in 1838 from the firm of Sarpy and Fraeb. The fort had been backed by the powerful American Fur Company. An agreement was reached just after the negotiations for the fort were concluded: thenceforth, Bent & St. Vrain Company would not send trading parties north of the North Platte River, while the American Fur Company would no longer encroach upon the territory south of there.[9] Of the "cartel" thus formed, David Lavender commented, "And so in 1838 big business sliced up the western half of America.[10] There is every reason to think that Ceran St. Vrain negotiated this agreement by means of his close personal relationship with the family of Bernard Pratte, who was the head of the company that served as the American Fur Company's western office.

Bent's Old Fort was the most remarkable structure in the West until the mid nineteenth century and the most dominant feature in the history of the southwestern Plains. As David Lavender has pointed out: "In nearly two thousand miles from the Mississippi to the Pacific there was no other building that approached it. Only the American Fur Company's Fort Pierre and Fort Union up the Missouri were comparable."[11] Matt Field, a correspondent for the New Orleans Picayune who visited the fort in 1839 wrote that it was, "as though an air-built castle had dropped to earth. . . in the midst of the vast desert."[12] Did the Bents intend to impress and influence those with whom they dealt by the sheer size of the fort and its architecture, which evoked thoughts of grand castles? We cannot say with certainty, but we do know that the structure itself awed many who visited there. We know also that this worked on numerous occasions to the advantage of Bent & St. Vrain Company. By this and other means, the principals of Bent & St. Vrain were uncommonly adept at influencing persons from many different cultures and backgrounds to act for the benefit of the company. For a quarter-century they exercised control of the region from their fort.

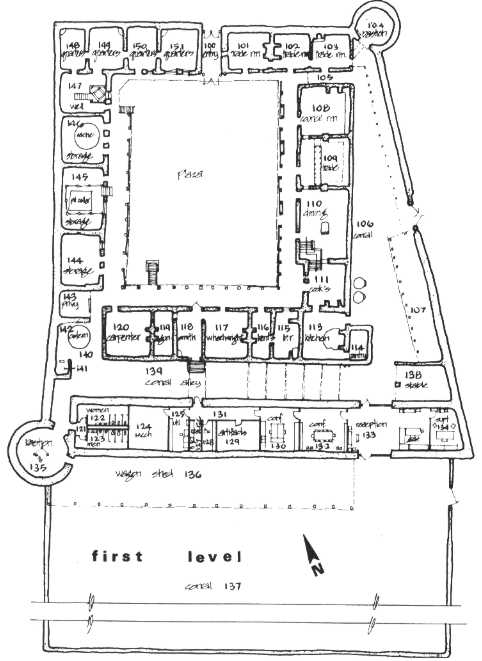

The best presentation of the dimensions of the fort, drawn from at least twenty-six firsthand written observations and three archaeological excavations at the site, was provided by George Thorson, the National Park Service architect in charge of the reconstruction of the fort (see fig. 10). Synthesizing from the various sources, he concluded:

The fort was divided into four main areas: the compound, the inner corral, the wagon room, and the main corral. The compound was essentially a rectangular core of buildings (115 feet by 135 feet) around an inner plaza (80 feet

by 90 feet). The inner corral on the east was a wedge-shaped area about 10 feet wide at the northeast bastion, expanding to 40 feet wide at the south. A 15-foot alley separated the compound from the 20-foot wagon house on the south and the 27-foot diameter bastion on the southwest corner. Therefore, the main fort was about 130 feet on the north front and 180 feet on the south with a 175-foot depth. Behind to the south was the main corral at 150 feet by approximately 14O feet (the precise dimension was lost due to earth disturbance). Twenty-nine rooms were identified on the lower level and 9 on the upper level. The enclosed rooms encompassed almost 17,000 square feet. The overall fort proper covered over 27,000 square feet, and the outer corral covered 21,000 square feet for a total of over 48,000 square feet, well over 1 acre.[13]

The fort was built without benefit of architectural drawings, and there was a lack of uniformity, evident in numerous aspects of the fort's construction. The thickness of the exterior walls varied from about 2 to 2.5 feet. A National Park Service employee who was on site for several years before reconstruction began has said that the foundations of the fort, previously visible at ground surface, were not straight, but meandered along a generally linear path.[14] Modifications and additions were made throughout the fort at various times during its use, and some discrepancies between documented and observed dimensions may be due to modifications that were made after documentation. Some of the most extensive of these were made during the years 1840-41 and 1846, as activities that culminated in the Mexican War intensified.

Archaeological evidence has indicated that the two most distinctive features of the fort, the towers or "bastions" at the northeast and southwest comers of the fort proper (excluding the main corral) were of different diameters. Although Lieutenant Abert, a skilled illustrator who visited the fort in 1845 with the U.S. Army, recorded the diameter of both bastions as 27 feet, archaeological examination of the remains did not verify this. The southwest bastion is 27 feet in diameter, but the northeast is only about 20 feet.

During the fort's occupation, eight visitors recorded estimates of wall height, and these ranged from 15 to 30 feet, the average estimate being about 19 feet.[15] Only one visitor, John Robert Forsyth, estimated the height of the bastions. Forsyth, who stopped at the fort for a few days in 1849 on his way to California to search for gold, recorded in his journal that the bastions were 25 feet high.[16] The attached main corral walls were not as imposing as the walls of the fort proper, but they could be defended by arms fired from the fort in an attack. The walls here were probably 6 to 8 feet high and, by some accounts, were planted on top with thick

Figure 10.

Plan view of the two levels of Bent's Old Fort. (Courtesy Colorado

Historical Society, Denver; from George A. Thorson, "The

Architectural Challenge," Colorado Magazine [Fall 1977]: 112-113.)

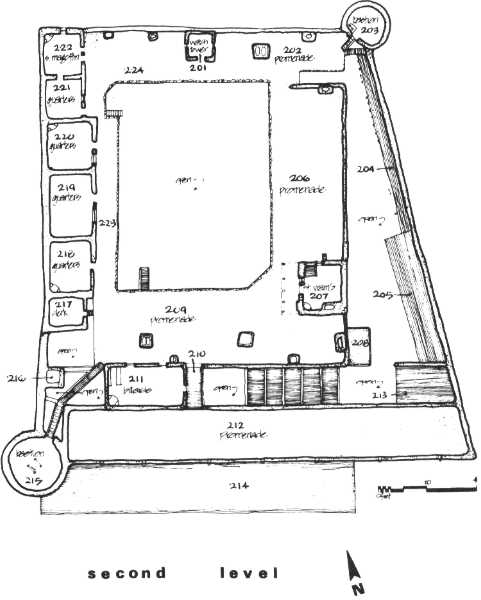

Figure 11.

Aerial view of the excavated foundation of Bent's Old Fort,

taken in 1964. (Courtesy Colorado Historical Society, Denver.)

cactus—a reasonable precaution in a country where horse stealing was an honored occupation.

From overhead, the entire structure would have appeared trapezoidal (fig. 11). The two corners thus produced, one obtuse and the other acute, afforded less cover to a person approaching from the back of the fort than would have two corners of 90 degrees. Without this aspect of the fort's design the corral area would have been less open to surveillance from the bastions and second floor of the fort.

It is plain that the fort was constructed to withstand any attack the Plains Indians might mount, and perhaps an attack from the Mexican army as well. Entry to the fort was restricted to a sort of a tunnel, a zaguan, in the front. The door to the zaguan was of stout wooden planks, sheathed with iron. Above was a watchtower with windows on three sides and a door on the fourth, providing views in all directions. A telescope assisted the watchman on duty. In the sides of the zaguan were small windows, which could be firmly closed or opened, so that goods could be passed to those Indians who were denied full admission to the fort. A brass cannon, mounted atop the northeast bastion, was fired on special occasions with an impressive report. Both bastions were filled with arms. Grinnell claimed:

Around the walls in the second stories of the bastions hung sabers, and great heavy lances with long sharp blades . . . for use in case an attempt should be made to take the fort by means of ladders up against the walls. Besides these cutting and piercing instruments the walls were hung with flintlock muskets and pistols.[17]

A large American flag flew from a pole adjacent to the west side of the watchtower, proclaiming the presence and power of a young country marching westward.

On the inside, the design of the fort showed the influence of both Pueblo and Spanish architecture. Room blocks formed the perimeter of the fort, about twenty-nine rooms on the ground floor, perhaps 15 by 20 feet in size. The tops of these room blocks were fiat, and a man could take cover behind the parapet that was formed by the fort's exterior wall as it extended above the roof of these rooms. More rooms were added to form a full second story along the west side of the fort; rooms were also built atop the southeast comer. Huge vigas, cottonwood trunks, formed the superstructure of the fort and were visible in the ceilings of the rooms. Almost every room had a fireplace for warmth in the winter and on chilly evenings. During the heat of the summer, the thick adobe walls provided cool shelter.

Some rooms were for sleeping, but more were for other uses. On the first floor were storage rooms, the trading rooms, the kitchen and dining hall, and workshops for tailoring, carpentry, and blacksmithing (where activity was as incessant as in the kitchen). An office for clerks was located on the second floor. Also on the second floor was a special, large room where the fort's owners entertained friends and visitors; eventually this room contained a billiard table and bar. Usually the elite of the fort's rigid social hierarchy lived and socialized on the second floor. It appears that the Bents and St. Vrain may have had rooms on both floors, and may have had access to both by means of stairways located within or just outside their quarters.[18]

When completed, the fort could house about two hundred men and three to four hundred animals. It was staffed by almost every. race and nationality that had come to the West. In addition to accommodations for those that slept within the fort's walls, many Indian lodges were frequently set up near the fort, and the numbers of Cheyenne and Arapaho who occupied them added to the activity at the fort during the day.

Bent's Old Fort dominated trade in the Southwest for almost two decades. This trade yielded immense profits in furs and silver, profits that

American businessmen had sought for decades. At the beginning of this period, the fort was a unique American presence; at the end, the area it occupied became a part of the United States.

Many of those closely associated with the fort are well known to historians, and some are familiar to almost all Americans. Perhaps the best known of those who had close ties to the fort is Kit Carson. Popularly known also are Thomas Fitzpatrick, Bill Sublette, "Uncle Dick" Wootton, "Peg-leg" Smith, and other trappers and traders. Virtually every American active in the Southwest who had any influence in commercial or political events in the second quarter of the nineteenth century visited the fort. This included all of the traders and trappers in the region. The fort was used as a staging area by General Kearny's Army of the West just prior to its invasion of Mexico at the outbreak of war in 1846, and the fort had effectively operated as a center for the collection of intelligence for that war for many years before the invasion.

Bent's Old Fort provided rich financial rewards to those associated with it. By 1840, the trading profits of Bent & St. Vrain Company were second only to those of the American Fur Company.

Prehistoric Trade Between Pueblos and Nomadic Groups

The key to the success of the Bent & St. Vrain Company was the ability of its principals to link existing networks of trade with the global system that Bent & St. Vrain represented. Trade networks in the region had been well established in prehistoric times. Some archaeologists suggest that trade between the eastern frontier Anasazi-Pueblo peoples in the Southwest and the nomadic tribes occupying mountain and plain areas may have been initiated because of the need for meat protein by the agricultural Anasazi.[19] Timothy Baugh has noted that agricultural societies in the Southwest were migrating to defensible positions near dependable sources of water and engaging in trade with more nomadic tribes by A.D. 1400.[20]

The process was accelerated by several climatological and cultural occurrences. Around A.D. 1300, a drought caused the relocation of a number of Anasazi-Pueblo villages from what is now southwestern Colorado to various spots along the Rio Grande, in what is now New Mexico. The construction of Taos, along with several other pueblos that quickly be-

came locales for trade with the more mobile Indians, was begun during the fourteenth century. Trade routes were well established with civilizations in central Mexico and with groups on the Pacific coast by that time.[21]

The Proto-Historic Period

European contact began in earnest in the sixteenth century, encroaching upon North America from three directions. From these earliest meetings between Europeans and Native Americans emerged a pattern that would be repeated many times and in many places, including the nineteenth-century southwestern Plains and Southwest.

On the East Coast, European fishermen began exploiting the waters off Labrador, Newfoundland, and New England, putting ashore occasionally to obtain supplies and make repairs. Before long, sailors were making regular summer campsites at which nets were mended and fish were dried and smoked prior to the return voyage. Fishermen soon were engaged in barter with Algonquians, trading European goods for furs. The fur trade, here and across the continent, set off a chain of economic, social, and ideological occurrences that led eventually to European conquest of the continent.

European settlement began early in the seventeenth century with the death of Philip II in 1603 and the end of Iberian control of the Atlantic. In the next thirty years, Jamestown, Quebec, Fort Nassau at Albany, New Amsterdam, New Plymouth, and Massachusetts Bay were founded.[22]

Native Americans quickly discovered that their traditional activities could be more easily, efficiently, and effectively carried out through the use of European goods. Metal implements like knives and axe heads were superior to those made by native technologies. Firearms in some landscapes and situations enhanced the productivity of hunting and offered an advantage in armed conflict. Blankets were lighter, and, for their weight and volume, warmer than furs. Other trade goods had less utility but were soon highly desired; perhaps foremost among these was liquor. Native Americans also wanted items that could be used for decorative purposes.

Competition and conflict among Indian groups turned desire for trade goods into need. Given the voracity of the European appetite for furs, hunting and trapping grounds were soon completely "harvested," leading the natives engaged in the pursuit of furs into the territories of others. This conflict was exacerbated by competition among Europeans from

different countries. The English and French, for example, vied with one another for furs that they obtained from Native Americans. In doing so, they formed alliances with specific Native American tribes: the English traded with the Iroquois and the French with the Huron. They encouraged their allies to wage war upon the tribes that were assisting the competing European country. Those attacked could only draw more closely to their European allies. Eric Wolf observed that:

Everywhere the advent of the trade had ramifying consequences for the lives of the participants. It deranged accustomed social relations and cultural habits and prompted the formation of new responses—both internally, in the daily life of various human populations, and externally, in relations among them. As the traders demanded furs from one group after another, paying for them with European artifacts, each group its ways around the European manufacturers.[23]

Wolf also noted that the trade changed both the character and intensity of Native American warfare. Displacement of populations from their habitat and near annihilation of whole populations through the introduction of European disease and military technology began early and continued unabated all along the eastern "front." As just one example of this, the Abenaki of the Maine coast were one of the first Native American groups with which Europeans traded for furs, beginning in the seventeenth century. By 1611, the Abenaki population had declined from about 10,000 to 3,000, most who died having succumbed to the European diseases to which they had no immunity.[24] A great wave of disease, population displacement, and warfare swept west, ahead of the presence of the northern Europeans in the New World.

While the English, Dutch, and French advanced from the east, another group of Europeans was moving into the New World from the south and west. Disease may have been an even greater factor in the social dislocations here. Alfred Crosby cites Spanish records that indicate approximately fourteen epidemics in Mexico and seventeen in Peru from 1520 to 1600. Joseph de Acosta recorded that by 1580, in several coastal areas occupied by Spain, twenty-nine out of each thirty Native Americans had died, and he thought it likely that the rest would soon follow.[25] The susceptibility of the native population to European diseases continued, evidenced by the comment of a German missionary in 1699 that "the Indians die so easily that the bare look and smell of a Spaniard causes them to give up the ghost."[26] Crosby speculates that so great was this susceptibility. that the native messengers who brought news of Spanish arrival may have car-

ried fatal infections with them, killing the recipients of the message before they ever saw, the invaders.[27]

Ideology and the Europeans

Scholars of all stripes, but particularly historians, have paid more attention to the ideology. of the Spanish than of the northern European groups that assaulted the New World from the east. Almost certainly this is because studies have been written from the Anglo-Saxon point of view. The motives of the northern European intruders from this perspective seem obvious: they were "economic" and therefore "rational." Most who have dealt with the subject have not considered northern European motives as ideologically based, although identification as such is implicit in William Cronen's book, Changes in the Land, and explicitly made by marxist-oriented theoreticians like Mark E Leone, who draws from Althusser's treatment of ideology.[28]

Spanish motives, then, in contrast to Northern European ones, have been regarded as less tied to "rational" goals like the establishment of industrial modes of production, and therefore they have seemed more curious. Recently, William Brandon proposed in Quivira that the promise of treasure, based in mythology. but encouraged by the successes of conquistadors such as Cortez and Pizarro, determined the nature of Spanish-Native American interaction in the New World.[29] The obsession with treasure caused the Spanish to overlook the more "realistic" economic opportunities that might have been enjoyed by taking advantage of Native American trading networks.

Brandon was more charitable to the Spanish than many earlier historians, who subscribed, as David Hurst Thomas observed, to the leyenda negra, the "Black Legend," which "systematically overlooked and belittled Spanish achievements." The legend held that Spain was motivated purely by "glory, God, and gold." In pursuit of their ends, the Spanish were cruel, bigoted, arrogant, and hypocritical.[30]

Thomas took issue, of course, with such disparaging remarks about the Spanish national character, yet he recognized the special place of religion in the Spanish occupation of the New World, emphasizing the "Hispanic master plan for missionization as a part of a strategy. for controlling the New World."[31] In the eighteenth century, a preoccupation with the establishment of capitalistic enterprise in trade and manufacturing

began to displace increasingly moribund traditional religious institutions as primary agencies of social organization in British colonies, but this did not happen in the Spanish-held colonies.[32]

Ray Allen Billington stressed what he saw as the desire of the Spaniards to "save" what they regarded as lost souls while bettering the lot of the natives:

Their task was not only to win souls, but to teach agriculture and industries which would convert Indians into useful citizens. Hence, each missionary was not only a religious instructor but a manager of a co-operative farm, a skilled rancher, and an expert teacher of carpentry, weaving, and countless other trades. The skill with which they executed these tasks attested to their considerable executive talents, just as the ease with which they pacified the most rebellious red men demonstrated their kindly personalities and diplomacy. Only rarely was the calm of a mission station marred by a native uprising; most Indians found the security of life in a station, the salvation promised them, and the religious pageantry ample compensation for the restrictions imposed on their freedom. Usually ten or more years were required to win over a tribe; then the station was converted into a parish church, the neophytes released from discipline and given a share of the mission property, and the friars moved on to begin the process anew. The mission station was a dynamic institution, forever intruding into new wildernesses, and leaving behind a civilized region.[33]

This approach did not succeed against the competition introduced into this area of the New World by other European countries, especially when the Spanish were dealing with the more nomadic Native American groups. In fact, it eventually worked to the disadvantage of Spanish hegemony:

As on other borderlands where Spanish, French, and English civilizations clashed, Spaniards failed to win the friendship of native tribes because their frontier institutions were little to the liking of the red men. They offered the Indians salvation and civilization; the French promised brandy, guns, and knives. The Spanish urged natives to abandon nomadic ways for sedentary lives in mission villages; the Frenchmen learned to live as the natives did and succeeded. Only the French government's failure to exploit its advantage saved Spain's northern provinces during those years.[34]

Billington's interpretation of these events is echoed by others, including Lewis Hanke in an essay on Spanish attitudes toward Native Americans. Here Hanke made the statement that "Spanish conquest of America was far more than a remarkable military and political exploit . . . it was also one of the greatest attempts the world has seen to make Christian precepts prevail in the relations between peoples."[35] Hanke described the

debate that raged among sixteenth-century Spanish intellectuals as the colonial era began. It was an elaborate exchange between polar factions that operated within a European value and belief system. The inherent equality of all human groups was propounded by the Spanish Dominican, Bartolomé de Las Casas; the opposing position that Indians (and, presumably, other non-Europeans) were an inferior type of humanity was argued in the writings of Juan Gines de Sepulveda. The work of Spanish missionaries was consistent with the position taken by Las Casas; the ado ventures of the conquistadors and later military exploits with that of Sepulveda. Spanish policy in the New World varied according to the faction in ascendancy.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho

Neither Spain's military nor its missionaries could withstand indefinitely the economic and ideological assaults launched first by France and then the United States in what became the American Southwest. And winning the Southwest was to prove decisive for the United States in fending off attempts to control western North America notably by Spain, but also by France and England.

The highly mobile Plains tribes, who in battle were capable of besting contemporary light cavalry, were the "wild card" in this game for the control of the trans-Mississippi West. Of all of these groups, arguably the most important were the Cheyenne and Arapaho by virtue of their intimate association with the Bent & St. Vrain Company and the pivotal role played by that company in securing the dominance of the United States in the Southwest. The Cheyenne and Arapaho had realized the strategic significance of the opportunities presented by the disruption of traditional roles and ways of life that Native American groups experienced with the arrival of the Europeans. These two tribes were then in a position to capitalize upon the European entry into the already established Native American trading network.[36]

The Cheyenne and the Arapaho were once sedentary farmers inhabiting areas near the Great Lakes. Historical and archaeological records indicate that by the late seventeenth century the Cheyenne were in present-day Wisconsin and Minnesota, while the Arapaho inhabited portions of Minnesota and Manitoba (fig. 12).

Sometime after 1750 the Cheyenne adopted a radically more mobile

Figure 12.

Cheyenne migrations from the late seventeenth through the late nineteenth

centuries. (Illustration by Steven Patricia.)

lifestyle. Just before this time they had been living on the Cheyenne River in what is now North Dakota, where they had been semisedentary, engaging in enough agriculture that they were trading corn and vegetables to neighboring tribes. Then they acquired the horse in order to hunt buffalo more successfully.[37] According to Virginia Cole Trenholm, the Arapaho possessed the horse as early as 1760.[38] The introduction of the horse into Cheyenne and Arapaho cultures enabled a dramatic expansion of trading activities for these groups. By 1780, both Algonquian-speaking groups were in the upper Missouri River Valley, where they formed an alliance that has persisted to the present (see fig. 12). The precise reasons for their movements can, of course, never be surely known, but surely the first of these was the dislocation of other Native American populations.

By the 1790s, Baron de Carondelet, the Spanish governor of Louisiana, who had chartered the Missouri Company (properly the "Company of Explorers of the Upper Missouri"), regarded the Cheyenne as the shrewdest of the trading Native American groups with which he dealt. They often represented the Arapaho, who were shy with strangers but who produced buffalo robes much in demand by virtue of their meticulous preparation and the quill work with which they were decorated.[39]

This is not to say, of course, that the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and other Plains groups had not been involved with trade before they acquired the horse. The Plains network encompassed the very large area of the Plains and was linked to trading systems in the Great Basin, the Plateau, and the Southwest.[40] Abundant historical evidence reveals that trade was established between the southwestern Pueblo and the Cheyenne and Arapaho, and also between the Pueblo and the Comanche, Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, Pawnee, and Sioux.[41] As we have seen, there is also plentiful evidence of prehistoric trade between the Pueblo and the Plains tribes.

Donald Blakeslee has hypothesized that the trade system grew out of a need for intersocietal food distribution.[42] Great quantities of food were typically exchanged during a trading visit. Blakeslee cited the work of Fletcher, who observed that the entire meat production of a buffalo hunt was sometimes given away as a part of the calumet ceremony that traditionally accompanied Plains trading visits.[43] In addition, feasting was perhaps the most prominent feature of these trading visits. Goods were exchanged that were used in food procurement; later, these goods included horses.

Trade was carried out in a ceremonial context in which advantage in

the short term was not the first priority of either party to the trade. In fact, almost any article of trade could be obtained by a party in need by the simple expedient of sending a delegation to those possessing the desired items to "smoke" with them. After having shared tobacco with the visitors, the hosts would be committing a serious breach of etiquette if they were to deny any request made by the visitors.[44]

Another indication of the ceremonial basis for trade was the redundant nature of much of it: Groups would trade for items that they had already or for which they had little or no need. All trade was accompanied by displays of exquisite etiquette, with those hosting the traders displaying every courtesy. So intense was the desire to engage in trade, so urgent was the need to establish thereby an identity in the fast-changing world of the nineteenth-century Plains Indian, that it produced behavior that might seem bizarre to those accustomed to present-day exchanges in the United States. Plains Indian trading behavior puzzled even the nineteenth-century traveler Lewis H. Garrard, who recounted several trading episodes in the famous journal of his 184-7 travel down the Santa Fe Trail. One of these is as follows:

On my neck was a black silk handkerchief; for this several Indians offered moccasins, but I refused to part with it. At last, one huge fellow caught me in his arms and hugged me very. tight, at the same time grunting desperately, as if in pain; but one of the traders who understood savage customs said that he was professing great love for me. . .. So pulling off the object of his love I gave it to him.[45]

Garrard also reported an incident in which an Indian brave threw himself on the ground and cried at Garrard's refusal to trade with him.

Such recorded behavior indicates desire for enduring, kin-type relationships established by the ritual of trade much more than desire for the objects that might be obtained by trade. Ceremony not only secured an identity for participants but also had a more long-term practicality than did the sort of exchange in which the object was to obtain the greatest profit per trade. It set up relationships that insured the availability of food in times of famine. Thus Blakeslee saw the well-documented "smoking" for horses and other items as a degradation of a calumet ceremony, in which the smoking of catlinite pipes by leading individuals of two social groups set up a fictive kinship relationship between them.[46] This ceremony was the centerpiece and underpinning of a trading system that Blakeslee postulated, partly on the basis of archaeological evidence, to have evolved

during the thirteenth century, A.D. He regarded the trading network served by the ceremonialism to be a response to what is called the Pacific Climatic Episode (A.D. 1200-1550), when a markedly drier climate increased the danger of drought and accompanying famine to the groups involved in the network.[47] The greater the distances between trading partners, the greater the insurance, since greater distance would lessen the likelihood that the trading partner would be affected by the same drought. The most effective network, then, would be the largest possible. An environmental impetus for the trade with the southwestern Pueblo in the thirteenth century A.D. , incidentally, would accord well with Timothy Baugh's idea that trade between the pueblos and the Plains groups increased as the Anasazi-Pueblo grew more focused on an agricultural technology and lifestyle.

By the early nineteenth century, bands of Arapaho were frequenting the area of the upper Arkansas. Bands of Cheyenne soon followed. There they could harvest Spanish horses and pursue their role as middlemen in the trade with the most remote of the Plains tribes, with the Pueblo tribes, and with the Spanish. They brought to the region British goods, obtained, for the most part, from Missouri River Indians. It was about this time that the Cheyenne split into Southern and Northern Cheyenne, and the Arapaho into Southern and Northern Arapaho. The continuing trade between the southern divisions of Cheyenne and Arapaho and the Bent & St. Vrain Company maintained and deepened their distinct identifies. The other Native American groups mentioned were involved in trade with Bent & St. Vrain Company in one way or another, too. The most important pueblos to the Plains trade were those at Taos and Pecos. Bent & St. Vrain Company negotiated a position that usurped in large measure the traditional roles of the Taos and Pecos pueblos (and others) and the more recent role of Spanish Santa Fe. As noted, the company then linked this network with the emerging eastern United States-European mercantile system.

As an illustration of just how well established the Plains trading network was by the time of the American entry into the fur trade of the trans-Mississippi West, consider that Lewis and Clark found iron-headed war clubs among the Pahmap Indians of Idaho—war clubs traded by those on the expedition to the Manna at their village on the Missouri River while on their way west. In a year the war clubs had moved 700 miles and, as Lewis and Clark reconstructed, through the hands of at least three tribes.[48]

The Native American "Wild Card"

The pattern of increased conflict between erstwhile Native American trading partners who allied themselves differently to competing European (and, in this case, American) factions was as much present in the southwestern Plains and the Southwest as it had been elsewhere, earlier, in the New World. Somewhat exacerbating this pattern was that certain traditional and ceremonial components of trade deteriorated as capitalistic aspects amplified. One instance of this has already been cited: The calumet ceremony, once the highlight of the trading visit, came to be practiced in a much attenuated form, one referred to as "smoking" for desired items. Although trade would still serve as an instrument of in-terband and intertribal cohesion, it would also provoke competition and conflict. Jockeying for position by dislocated and disarticulated Native American tribal groups would increase.

By the early nineteenth century in the southwestern Plains, the competition between European traders had narrowed for the most part to that between the Americans and the Mexicans, although there was a fear on the part of both of these nations that the British, farther to the west, might be waiting in the wings.

The position of New Spain in this competitive configuration had been, of course, usurped by Mexico. Before the successful revolt of 1821 New Spain had been assaulted by both the French and the Americans. The French gained increasing influence and an enlarging share of trade because they adapted well to Native American ways rather than trying to convert Native Americans to Christianity as did the Spanish. While the Spanish apparently succeeded to some degree with the sedentary Pueblo tribes (much of this conversion was eventually revealed to be superficial), the nomadic groups steadfastly resisted Spanish attempts at salvation.

In 1803, when the United States acquired Louisiana from France, the situation for New Spain turned from bad to worse:

For half a century after New Spain flung its protective wall across the northern approaches to Mexico, the feeble barrier underwent a constant assault. . .. Of the aggressors the most dangerous were Anglo-American frontiersmen, and their shock troops were the fur traders.[49]

Zebulon Pike had made his famous foray into New Mexico in 1806, not long after the American acquisition of Louisiana. This must have confirmed the fears of the Spanish that the Americans had their eyes on New

Mexico, had such confirmation been necessary at all. In 1804 the former Spanish lieutenant-governor of Louisiana expressed what many of his countrymen were thinking when he wrote that the Americans intended to extend "their boundary lines to the Rio Bravo."[50]

The expansionist ambitions of the United States were apparent to the Spanish. So too were the maneuvers that the Americans could undertake preparatory to an actual invasion. The Spanish understood that the Plains Indians could either impede or enhance the effectiveness of the American strategy of infiltrating New Mexico through the fur trade. David J. Weber, in his book The Taos Trappers: The Fur Trade in the Far Southwest 1540-1846, reported that Baron de Carondelet worried about American attempts to expand their fur trade through "control" of Native American groups.[51] And Spanish officials by 1803 had come to see the Plains Indians as an essential buffer to American encroachment, if their loyalty could be obtained through participation in the Spanish fur trade.[52]

To this end, during the ten years before the end of Spanish rule in New Mexico, the Spanish traders made a concerted and successful effort to expand their business beyond their traditional trading partners, the Comanche, to include the Kiowa situated on the Arkansas, the Pawnee who then frequented the Platte, and the Arapaho who moved between the south Platte and the Arkansas.[53] They also continued their policy, of driving out or jailing any foreign trapper or trader who ventured into New Mexico. One of these, Jules de Mun, learned from the governor in 1817 of the Spanish fear that the Americans were building a fort near the confluence of Rio de las Animas and the Arkansas. The Spanish were frightened enough of this prospect to send troops to the site. When they found nothing, de Mun was released. The Spanish, in fact, were premature in their anxiety by more than a decade, as the site of the imagined fort was very near that of Bent's Old Fort.[54]

Spanish efforts to create a viable fur trade with the Indians were hampered by the structure of Spanish society. There was no middle class to carry out this work. The only persons in Spanish colonial society with enough economic and social sophistication to trade in furs were the very persons formally prohibited from doing so, the governors of the provinces and the clergy. Although many governors and some clergy did engage in such trade, the illegalities rendered their efforts problematic and most likely less effective than they might have been in other circumstances. Later, just before Mexican Independence, would-be Spanish traders were hamstrung by the most practical of considerations: the severe shortage of trade items with which to barter with the Indians. This lack made many attempts

at trade with native groups incredibly small-scale affairs. Sometimes traders would endure the hardships and risks of travel to Native American groups with only a few bushels of corn to offer and would receive only a few hides in return.[55]

In summary, the fur trade under the Spanish was not well developed because of three related factors. First, as just noted, there were virtually no fur traders, that is, people trained and experienced in the trade and committed to pursuing it as a way of life. Second, the Spanish found it difficult to accommodate effectively the Plains and Southwest Native American trading systems already in place. To acquire furs, they relied primarily upon the encomieda system, a taxing of the Pueblo Indians by Spanish government officials. These Native American groups were sedentary and much more susceptible than were the Comanche, Apache, Kiowa, Ute, and other mobile tribes to Spanish coercion. Weber recorded a monthly payment from Pecos pueblo in 1662 as sixty-six antelope skins, twenty-one white buckskins, eighteen buffalo hides, and sixteen large buckskins.[56] The Pueblo tribes, of course, would have acquired these hides for the most part from Plains Indian groups, through the trade fairs which harkened back to the thirteenth century.

The sorts of furs rendered as tax in this example illustrate the third characteristic of the fur trade in the time period. Almost all furs traded were of "coarse" varieties, as opposed to the "fine" furs which were the main interest of the Americans, English, French, and, much earlier, the Dutch. There was a sense among these parties that pelts taken from southern areas like New Mexico might not be of the same quality as furs from farther north, where animals were subjected to more severe winters. Nonetheless, New Mexican fine furs were valuable. John Jacob Astor himself, while aware that beaver furs from New Mexico were "generally not so good" as those from farther north, still desired the New Mexican pelts because "the article is very high it will answer very well."[57] Perhaps contributing to a certain initial lack of interest in fine furs on the part of the Spanish was that fine furs may not have been as fashionable in Spain and southern European countries as they were in northern Europe.

This, however, did not lessen their value as trade items with northern European countries. "Fine" furs—especially beaver, but also weasel, fox, and ermine—were fashionable in northern and many western European countries and so commanded much higher prices in the mid nineteenth century than did the rough variety. Adding to their appeal was that they were more easily transportable than rough furs.

But the Spanish could not really participate in such trade because New

Mexicans themselves were not collecting pelts, and the fine furs were not available through the encomieda system because the Plains tribes brought only the coarse variety of furs to the pueblos. Plains Indians had been harvesting the larger skins, much more practical for their uses, for centuries, and a way of life had grown up around these harvesting activities. Bolstered by ideological systems, such behavior patterns are not easily altered. While there are numerous historic examples of Native American societies emphasizing certain economic activities at the expense of others after trade had been initiated by the Anglos, there are few examples of them adopting totally new economic activities. The adoption of farming by Plains Indians, for example, was resisted because it was not perceived as a meaningful activity. It seems likely that trapping beaver was similarly uninteresting to the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Sioux, Ute, and other tribes during the Spanish period, as there are numerous references to the unreliability of Plains Indians as a source for beaver pelt, even when the value of these pelts had been amply demonstrated to them.

American Entry into the Southwestern Fur Trade

The structure of Plains Indian culture worked to the favor of the Bents and their company. The value of beaver pelts dropped dramatically even before the midpoint of the century as the winds of fashion shifted and beaver skin hats grew passé among the gentry (they were replaced by silk hats). As the demand for beaver pelts diminished in Europe, there was a coincidental rise in the value of coarse furs such as buffalo, which were used as carriage lap robes, in coats, as rugs, and for other purposes that had become fashionable. Bent & St. Vrain Company, of course, employed the buffalo robe trade as the mainstay of their trading enterprise, achieving a vertical integration through the close ties they so effectively cultivated with the Cheyenne and the Arapaho and, through them, other Plains groups.

But initial interaction between Americans and Native Americans in the southwestern Plains was not auspicious. Unlike the Spanish and English, American fur traders often did their own trapping, rather than relying upon Indians to bring them furs. As noted previously, beaver trapping was not so ingrained in southwestern Plains Indian culture as in the Indian cultures of the Northeast, and Americans were therefore much more

efficient at collecting beaver pelts than were the Plains tribes, which provided additional motivation for the Americans to engage in trapping themselves. Another difference between the Americans on the one hand and the English and Spanish on the other was that Americans were often independent businessmen or were grouped in competing companies, whereas the European fur traders were part of monopolistic companies supervised by their governments, like the Hudson's Bay and the Missouri companies. The United States had established government trading posts, called "factories," in 1796 to protect Indians against the unscrupulous practices of many traders, but in 1822 they were abolished. The private sector had complained vigorously that they constituted unfair competition. After the demise of the factory system, which coincided with the opening of Mexico to trade, American entrepreneurs rushed into the frontier and began to rapidly strip it of its wealth.

The Native Americans acted to preserve their position as trading middlemen. The Arapaho, for example, would not allow traders to trade in their country. Not only did the traders present a potential threat to their position, the Arapaho could acquire the goods they desired elsewhere. They visited the Arikira on the Missouri to trade furs and horses they had acquired in the southwest for European goods and corn. Some of these European goods, of course, included firearms, gunpowder, and lead. At the same time, Arapaho were trading buffalo robes and beaver pelts with the Spanish (actually, the Comancheros) to the south for firearms and other goods. When in 1811 Manuel Lisa sent Jean Baptiste Champlain to trade with the Arapaho in their southwestern home and the Spanish traders in Santa Fe, the Arapaho killed him and two of his party. The Arapaho attacked a number of other parties who ventured into this territory for the same reason: to keep intruders out of their trading area.[58]

Between about 1810 and 1820, the Arapaho and the Cheyenne gradually moved south to the Arkansas River, lured by Spanish horses and Spanish trade. Both groups stoic horses from ranches in Chihuahua and Durango, which they could now trade to the Americans along with the buffalo robes that the horses helped them acquire. The Americans frequented the ancient trading rendezvous at Taos, where they brought guns, whiskey, and tobacco.[59] The lure of such items, in themselves, was not enough to generate a warm welcome for the Americans among the Cheyenne and Arapaho, since the American presence could threaten the position of the tribes within the trading configuration. Native American traders, after all, ranged as far as Missouri, the Rockies, and Canada, as well as into New

Spain. Such travels provided alternate means of access to manufactured goods. Although the Plains Indians would trade on their own terms with Americans, the tribes continued to harass Americans who entered tribal territory without their permission. For this reason several American trappers were killed near Taos in 1823.[60]

Mexican Independence

Native American hostility toward Americans may have peaked in the 1820s, as increasing numbers of trappers and traders from the young country to the east took their chances along the Santa Fe Trail, lured by the opening of New Mexico that came with Mexican Independence in 1821. Uninvited and underarmed trading parties were quickly divested of their horses, mules, and goods. By 1832 this hostility had begun to lessen[61]

It is not coincidental that hostilities began to abate as the first trading posts were erected in the area, allowing Native American groups to trade furs (and other items) to the Americans for merchandise. In this way, the Indians' position as middlemen was resurrected and institutionalized. The most notable and successful of the companies who entered the southwestern Plains was Bent & St. Vrain Company. The fortunes of Bent's Old Fort rose with the rising tide of buffalo robe fashionability.

The new profitability of the trade in buffalo robes provided a strong and stable economic base for the relationship between the Bents and their compatriots on the American side, and the Cheyenne and Arapaho on the Native American side. Weber noted, "Unlike beaver pelts, which few Indians trapped, buffalo robes were readily available through trade with the Indians so that the fur trade could be carried out at strategically located fixed trading posts.[62] Thus the Native Americans could pursue activities that they found satisfying and retain their position as middlemen.

American entrepreneurs also found a much more cordial reception in New Mexico after Mexican Independence. New Mexicans possessed almost no manufactured goods during the Spanish colonial era. Their society was preindustrial. Just as there was no sector of the populace exclusively occupied with trapping or trading for furs, so there was no one engaged in the production of glass, cloth, pots and pans, ceramics,

knives, and other such utilitarian items, except for personal use. Ceran St. Vrain, who ultimately made New Mexico his home, was struck with the evident poverty there, even in the cities.[63] New Mexican dwellings were dark places and rudely furnished, with no glass for windows, often no chairs, beds, or tables, and few ceramics with which to eat. Meals were often cooked in a single pot and eaten by means of tortillas. Furs and blankets took the place of furniture, but even these were difficult to obtain, except by the elite who had the goods to trade for them or the coercive power to acquire them through taxation. Desirous of the products of American and European industry, the victorious Mexicans of 1821 welcomed American traders with open arms.

For a short time this welcome extended even to trapping in New Mexico. By 1824, however, the rush of Americans into the territory had prompted an alarmed central government to decree that only "settlers" be permitted to trap beaver. As it was, in the brief period between 1821 and 1824 when the official restrictions against foreign trapping had been abolished, Americans had been intermittently jailed or otherwise harassed by officials for engaging in trapping in New Mexico. These same officials saw the 1824 decree as an urgent necessity if Mexico were to realize any benefit from this resource inside its borders. Thus the remnants of the old power structure stepped in after a few years to restore what it regarded as a semblance of order to the newly independent state.

Although manufactured goods were earnestly desired from the American traders, there was a chronic shortage of specie during the 1820s with which to purchase such items. Pelts were soon accepted eagerly—indeed, pelts were as desirable as specie if not more so, because profits taken in beaver skins were not taxed. Here was another case in which the leadership in New Mexico saw the American intruders operating outside of the legitimate authority of the new state—and depriving the state of much needed revenue by doing so.

American interest in the opening of New Mexico was intensified because of hard economic times at home. Even farmers in Missouri found that they had to supplement their incomes with trapping in order to acquire scarce capital. Potential for profit in the fur trade was much increased when the United States government abolished its "factories." The bravest of the horde of traders drawn to the Missouri River by the abolition of the factory system ventured beyond, into the newly accessible territory, led on by stories of its largely untrapped streams. Thus, in its early years, trade on the Santa Fe Trail was dominated by traffic in furs. This put ad-

ditional pressure not only on these resources but also on the New Mexican government to control the activities of these newcomers.

American traders traveled to New Mexico in the summer, traded for what specie and furs they could, then stayed the winter to trap, returning home in the spring. As the political mood in Mexico turned against American trapping, increasing numbers were drawn to the small village of Taos. There authorities were not quite so watchful, and additional furs and other marketable items like blankets were available through the trading network nodules at Taos and Pecos pueblos. Taos was also attractive because it was located in the best beaver trapping area of New Mexico.

American trappers circumvented Mexican restrictions in devious ways, often with the collusion of certain Mexican authorities. Trapping permits for persons with Mexican names, for example, could be obtained by American trappers if a certain number of Mexicans were brought along on the trapping expedition as "trainees." Americans eventually claimed Mexican citizenship and frequently took Mexican brides. They set up households and diversified into other businesses. This strategy was adopted as quickly as possible by Ceran St. Vrain. St. Vrain acquired Mexican citizenship on February 15, 1831, which would have been just a month or two after he established the Bent & St. Vrain Company with Charles Bent. Thereafter, St. Vrain used the name "Severano Sanvrano" in his dealings in Mexico.[64] Simeon Turley, to cite just one other well-known example, also acquired Mexican citizenship. He then built a distillery and set about profiting from the sale of "Taos Lightning," much in demand locally and north of the border. Such expatriate Americans, who retained their patriotism without bothering too much to conceal it, were to play an essential role in the eventual American conquest of the territory.

By the late 1830s, the Mexicans had found a way to profit from the Santa Fe trade, and an embryonic middle class had formed. David J. Sandoval, who in recent years has reexamined the area's history from the Mexican point of view, noted that "as early as 1838 Mexican merchants may have transported the bulk of New Mexico-bound goods on the trail."[65] Sandoval's research indicates also a more sophisticated use of the centuries-old Indian trade fairs by the Mexicans during this time. The one at San Juan de Los Lagos, for example, lasted ten days each December. Trading done during this time was exempted from taxation, except for duties paid to the Mexican government upon entry of the goods into Mexico, and the incipient Mexican middle class used this opportunity to maximize their profits.

Mexican Independence and Native American Relations

In the quarter-century between Mexican Independence and the Mexican War, the Mexicans suffered much more from the depredation of Plains groups than did the Americans. The situation had been deteriorating for some years even before Mexican Independence, according to David J. Weber, who saw this as a fundamental rejection of Hispanic culture by the seminomadic Native Americans. In turn, the nomadic Native Americans were termed by Hispanic frontiersmen "indios barbaros," "salvajes," "gentiles," or "naciones errantes ."[66] Thus these "savage" or "barbaric" Indians were differentiated from the Pueblo Indians, who appeared more civilized to the Hispanics because of their sedentary and agriculturally based lifestyle.

It was precisely this sedentary way of life, based in agriculture or ranching, that made the Hispanic frontiersmen, the "pobladores," irresistible prey for many warlike tribes including the Apache, Navajo, Ute, Comanche, Kiowa, and Kiowa-Apache. As a military veteran said of the Apache, "war with this horde of savages never has ceased for one day, because even when thirty, rancherias are at peace, the rest are not."[67] This situation very likely obtained with all of the other tribes who engaged in raiding, too; harmonious relations with one band of a tribe did not necessarily mean that another band from the same tribe, or even individuals in the friendly band, would refrain from depredations. The conflict became ceaseless on the Mexican side of the Arkansas after Mexican Independence.

One reason for this further intensification of conflict after Mexican Independence was the waning of Mexican military power, which encouraged raids by the warlike groups. The Americans, however, were clearly involved in the escalating violence: The Mexicans were very aware that they were providing the seminomadic groups with firearms and ammunition. The Spanish had been careful about the numbers of such items and the ways in which they were parceled out, although they had encouraged the Indians to use firearms. In doing so, they attempted to make the Indians dependent upon them, hoping that they would lose their remarkable abilities with the bow and arrow. If this had occurred, the Spanish would have been better armed, because they offered the Native Americans only inferior firearms. Also, the Spanish had hoped that any uprising could be quelled simply by withholding ammunition and replacement firearms. This

strategy was not successful because the Plains tribes retained their skill with the bow and arrow, continuing to rely upon their traditional weapons as the mainstay for hunting and warfare. The Mexicans worried about the weapons and ammunition now freely available from the Americans. By the late 1820s, as Weber noted, New Mexicans believed that "American armaments had shifted the balance of power to the Indians."[68]

The American traders who moved into New Mexico after independence in 1821 also exhibited no prudence in supplying another item. This was whiskey, a key ingredient in the general breakdown of order among Native American groups. In the long run, this probably precipitated more problems for the Mexicans than did the greater availability of firearms.

At least as important, the Americans encouraged depredations by providing a ready market for stolen goods, particularly horses and other stock. In some cases this was unintentional, but in many others, it was not. In just one of numerous documented incidents, the trader Holland Coffee, in 1835, met with Comanche, Waco, and Tawakoni and "advised them to go to the interior and kill Mexicans and bring their horses and mules to him and he would give them a fair price."[69]

The Plains tribes that traded with the Bent & St. Vrain Company, especially the Cheyenne and Arapaho, became "wealthy:" They now had not only plentiful firearms and ammunition but also the tokens of value needed to attract warriors for raiding parties and to equip those parties with the supplies and magical fetishes needed to insure success. They also possessed the "medicine" that went with trade objects, enhancing their prestige and their ability and readiness to attract followers and allies in warfare. This increasing ability to acquire stock through raiding and furs through hunting, and the ready market provided by the Americans, produced some dramatic shifts in trading patterns and alliances—all of them toward the Americans and away from the Mexicans.

David Weber examined this realignment among the Ute. The Ute had been staunch trading partners and allies of the Mexican pobladores until about 1830. At that time Antoine Robidoux, an American of French descent, built two trading posts in their territory, one on the Gunnison River, the other on the Uintah River, in the area that is now Colorado. Seduced by Robidoux's guns and ammunition, the Ute no longer had need of the inferior goods offered by the old trading partners, the pobladores. It was not long before the pobladores, in fact, were seen as appropriate targets for Ute raids. By 1844, the Ute "war" on the pobladores had begun.[70]

Finally, we can see how certain sorts of traditional Plains Indian behaviors were amplified through the influences of the Americans. These

influences were not only the introduction of exciting new weapons and a large and ready market but also the dislocation of relationships among Native American groups. Westward-moving Americans were pushing Native Americans ahead of them. At the same time, new alliances were forged, for practical purposes, among tribes that might otherwise have warred. Thus Plains Indians like the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Kiowa-Apache for economic reasons could not wage war on the Americans—or on each other. Among the Plains tribes, though, the most meaningful of activities were those that proved prowess in hunting, raiding, or war. The new alignment of the Plains Indians on the American side (with the notable exception of the Comanche, as we have seen) both directed this orientation of behavior against the Mexicans and intensified it.

Now the rewards for raiding were doubled. One could not only count coup but also could gain added prestige by the acquisition of really substantial booty. The orientation toward raiding and warfare was further intensified as buffalo disappeared. In the absence of buffalo to hunt, there was for a man, according to the Plains Indians system of values and beliefs, little else worth doing than warfare and raiding.

The Preeminence of Bent & St. Vrain Company

By the mid 1830s, Bent & St. Vrain dominated the fur trade in the southwestern Plains and the Southwest, in large part because of the relationship the firm had established with the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Bent & St. Vrain Company had not secured their trading relationship with the Plains tribes unchallenged by other American traders, who were just as aware of the financial opportunities that had arisen with Mexican Independence. Although the precise chronology is fuzzy, the noted historian of the upper Arkansas, Janet LcCompte, believed that a trader named John Gantt was the "first Cheyenne trader on the Arkansas."[71] But this competitor with the Bent & St. Vrain Company was simply not as successful at establishing firm and lasting relationships with the Native American groups of the area.

It seems likely that Gantt alienated the Cheyenne and Arapaho from the beginning of his interaction with them. Although he was licensed to trade with the Indians, LeCompte reported that his real intention was to have his own men trap beaver, thus cutting out the Cheyenne and Ara-

paho as middlemen.[72] Even after Gantt decided to construct a trading post and deal with the Cheyenne and Arapaho on their own terms, he was outmaneuvered in the establishment of relationships with these potential wading partners.

Many sources record that William Bent made the decision to build his adobe fort near the Purgatoire after a visit by the Cheyenne Chief Yellow Wolf to his temporary picket stockade, which he had located farther up the river. Yellow Wolf is said to have told Bent at this meeting that the Cheyenne would trade with Bent if he would move his operation farther down the Arkansas, into the buffalo range and the traditional wintering ground of "Big Timbers."[73] The significance of this event is heightened in light of Weber's discovery that the Spanish had heretofore been engaging in trading rendezvous with the Plains tribes at this location, even as early as 1818.[74] This might well mean that Yellow Wolf's directions to Bent signaled the intention by the Cheyenne that he would replace the Spanish traders as the Cheyenne's primary trading partner and supplier of manufactured goods. This is a message that, given Bent's probable knowledge at the time, he could understand.

Although Bent did not move quite so far as Big Timbers, he did in essence follow Yellow Wolf's advice, embarking upon a cooperative association with the Cheyenne that would be firmly cemented in 1835. In that year he married Owl Woman, daughter of White Thunder, Keeper of the Sacred Arrows, and thus probably the most respected man among the Cheyenne. By doing this, William Bent became a Cheyenne himself. Many years later, when Owl Woman died, he married her sister, following Cheyenne tradition. Other intimates of the Bents married Cheyenne or Arapaho women. Kit Carson, for example, a friend and associate of the Bent family since childhood, took an Arapaho wife.

Perhaps the most telling incident in the competition for trade relations with the Cheyenne and Arapaho occurred in mid summer of 1834. Gantt had moved his trading operation, like Bent had earlier, downstream, just three miles west of—Bent's Fort. Copying Bent, Gantt was also building an adobe fort, replacing the stockade he had just abandoned. When a party of Shoshoni camped near Gantt's Fort, still under construction, Bent led ten of his men in an attack on the Shoshoni, killing and scalping three of them. He also encouraged the Arapaho and Cheyenne with whom he was trading to steal the Shoshoni horses. The Arapaho and Cheyenne needed little encouragement, being bitter enemies of the Shoshoni. This show of force by Bent had at least two effects. First, it intimidated and shamed Gantt, who was shown to be unable or unwilling to defend his trading

partners. It also demonstrated Bent's solid affiliation with the Cheyenne and Arapaho and strengthened that affiliation, since they banded together to defeat a common foe. William Bent may have had more than this rather devious end in mind when he precipitated the attack, since a witness stated that William said the reason for his action was that the Shoshoni had stolen some mules from his brother.[75] Whatever Bent's motivation, Gantt withdrew from competition for the Indian trade in the area not long thereafter.

With that, Bent & St. Vrain secured a powerful position in the fur trade. The friendship of the Cheyenne and Arapaho provided the company with a source of coarse furs and protection for the other aspects of their business, which included the trade in fine furs obtained from "mountain men" who would henceforth gather at the fort for supplies and companionship. The Cheyenne and Arapaho, in return, received manufactured goods and the associated "medicine," which could attract allies and intimidate enemies.

Eventually, the Bents encouraged the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples to make peace with some of their traditional foes. Such peace benefited the Bents because it facilitated trade with the enemies of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, thus expanding their ready source of buffalo robes. The Comanche, who generally stayed on the south side of the Arkansas, fell into this category. Because of the Bents' alliance with the Cheyenne, the Comanche considered themselves enemies of both parties. One instance of Comanche hostility, toward Bent & St. Vrain Company was the murder of the Bents' horse herder and the theft of as many as one hundred horses in 1839.[76] Also, Robert Bent, brother of William and Charles, was killed by Comanche warriors in 1841. Despite such incidents, the Bents were determined to trade with the Comanche, and also the Kiowa, who were not only enemies of the Cheyenne but also traditional trading partners with the Mexicans and, before them, the Spanish.[77] In acquiring these groups as trading partners, the Bents were incidentally moving them closer to the American side of a conflict that had long been developing with the Mexicans.

In 1840, the Bents' efforts paid off. In the summer of that year, at a location on the Arkansas near Bent's Old Fort, peace was made between the Cheyenne and the Arapaho on one side and the Kiowa, Comanche, and Kiowa-Apache on the other.[78] The peace was sealed with an exchange of items that both sides had obtained from Bent's Old Fort, including guns, beads, blankets, cloth and brass kettles. Very probably these were regarded as among the most precious objects the tribes possessed because of their "medicine." With this, the number of individuals with whom the Bent & St. Vrain Company could trade for furs was doubled. By the next

year, 1841, Charles Bent wrote to Manuel Alvarez in Taos that he expected 1,500 lodges of Comanche and an equal number of Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux that year. He wrote later that thirty-one Comanche and Kiowa chiefs had arrived in March at the fort, noting, "They have made peas [sic] with us."[79]

After the Mexican War

The principals of the Bent & St. Vrain Company had been greatly involved with the preparations for the Mexican War and were instrumental to the war's success. It is ironic that the war destabilized the area to the extent that the Bent & St. Vrain Company could no longer survive. Newcomers streamed in during the war and after American victory, and buffalo herds decreased rapidly. With these developments, the Plains tribes turned more than ever to raiding.

Comanche hostilities intensified from 1846 to 1849, with severe consequences for the company. In the summer of 1847, attacking wagon trains and troops on the Santa Fe Trail more ferociously than ever before, the Comanche took sixty white scalps, and they destroyed or stole about 330 wagons and 6,500 head of stock.[80] In 1848, the Kiowa responded by informing the Indian Agent for the territory, the old Bent & St. Vrain Company employee Thomas Fitzpatrick, that they would no longer be allied with the hostile Comanche but would join the peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho on the Arkansas River. Despite their action, the Comanche hostility and the general disruption of activities in the southwestern Plains that it engendered greatly curtailed Bent & St. Vrain Company's ability to carry out trade.

Ceran St. Vrain went to St. Louis in the summer of 1848 to dissolve the company. Charles Bent had been killed in the uprising at Taos in January of 1847. This left William Bent as the sole original principal of the firm, and the only one who remained on the Arkansas. In August 1849, William Bent packed up all that could be moved and set out downstream. After the wagon train had gone several miles, he returned alone.

What happened next is uncertain. What is known both from written accounts from that time and archaeological evidence is that his actions in some way caused a fire that substantially damaged what had been called his "adobe castle." One story was that the cholera epidemic at the fort prompted him to set barrels of tar burning in order to fumigate the fort,