The Reenactments

Jack Wise is more relaxed on this Independence Day than is the superintendent. Jack is the executive director of the Bent's Old Fort Historical Association, a private group that has been organized to support the park's activities. Though there are many special events today, his role is unchanged. He and his staff run the store. He feels confident that this is the soul of the fort, just as trade was in historic times. Visitors want

to take something back from their visit, almost demand it. A National Park Service study of visitor activity at Grand Canyon done some years ago, now legend in the Park Service, revealed that the average visitor spent about twenty minutes looking at the canyon, the rest of the time looking for or checking into hotels, perusing menus and eating, and buying souvenirs. (Though there are, of course, many who depart drastically from this average.) The National Park Service does not operate for profit and so delegates the provision of such services to concessionaires. Some of the concessions are run by private enterprises; others, like the one at Bent's Old Fort, are operated by nonprofit affiliates of the National Park Service.

Jack points out that visitors to the fort in historic times came here to do exactly what current-day visitors do, in one respect—to trade for things. And the things he provides are, to the best of his ability, almost exactly like what was purchased here in historic times (fig. 23). No rubber tomahawks here, he declares. The store stocks Hudson's Bay blankets, the real thing, including the white Bent's Fort blanket made especially for Bent & St. Vrain; custom blacksmithed hand tools, hardware, and cooking utensils; hand-made rifles; powder horns, not plastic but real horn, costing from $100 to $115 apiece ("but people buy them, they buy authenticity," says Jack); museum-quality reproductions of redware pottery; black silk scarves ("I pull them out with a flourish and say, 'for you, from the Orient'—they snap them up"); bricks of tea ("the kids can't get over them"). "It's all in the presentation," says Jack. "If you tell them about the item, how it was used and who used it in historic times, they'll buy it. They want to take home a piece of history."

Sales have increased dramatically since Jack took over responsibility for the concession. He attributes the success of the history association's concession to his ability and that of his staff to go into character. It is plain that they are very good. Dressed in period costumes, they seem like professional actors to me. Jack has a thespian's voice; it fills a room easily. He and his association people bring their acting skills to the concession, turning it into a reenactment as surely as is the dragoon camp down by the river.

Still, he is impatient to test the frontiers of reenactment in ways that the National Park Service will not allow. He hands me a flyer for an event he has planned through an organization with which he is affiliated, called Vistas of Time. Each year he has organized a program called "Polk Springs," named for the private ranch where it is held. He tells me that there are haft a million people in the United States who have been involved with reenactments, in one capacity or another, and it is from this

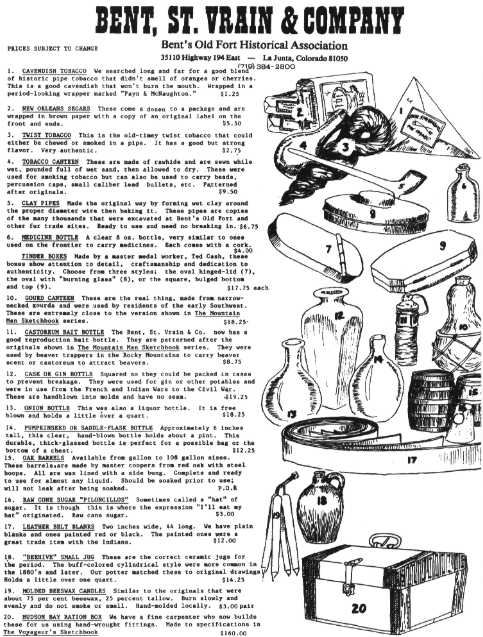

Figure 23.

Page from the 1990 sales catalog published by

Bent's Old Fort Historical Association

group that attenders are drawn. The ad runs, among other places, in magazines for reenactors. It reads, in part:

GREETINGS: THIS IS NOT A REENACTMENT!

We are looking for 100 soldiers right from the Civil War battlefields via the prison pen at Camp Douglas, Illinois, to come West with a galvanized Yankee Infantry Company and soldier in the Indian Wars of 1865 for five full days of very real living history.

This is not a club or regiment being formed with dues and meetings nor are you obligated to anyone in any way. This is strictly an in-depth living history experience where you sign up to soldier in 1865 on the southern plains in Comanche country for five full days. Then you are discharged.

Polk Springs is designed to be a "socio-learning" experience which means you will learn history as it happened and that you may enjoy yourself while learning to live in the past.

On Monday morning, prepare yourself mentally to go into 1865 and not return to the present until the following Friday. Conditions will be identical in every way humanly possible to those of 1865; tough, harsh, and bleak. The experience will wear on you physically and mentally.

Experienced as well as novice reenactors and living historians alike need understand that no one should be offended nor take anything personally. If you are shouted at, threatened or punished for some infraction, it is all in the context of the U.S. Army of 1865, not you as a person today. . . .

There will be no dances, no Sutler's Row, no military balls, no bands or canned music, no referees, no "firing demonstrations," no cars, no interpretive talks, no visitors, no tours, and no cam-corders. There will be virtually no 20th century for five days. This is not a typical event. There will be no reenactments of any battles, no one will "be killed" or "wounded."

HOWEVER, YOU WILL BE FIRING LIVE AMMUNITION!

Discipline by the officers and NCOs will be rigid and tough as it originally was. You will be in the Army for five days and you will be expected to follow orders. You will be in period first person 24 hours a day for five days. There will be no cession of duties at 4:30 PM or any other time to discuss the day's activities, drink cold beer, or listen to Civil War period music on boom boxes. . .. You will not live history as we or any museum or government agency interprets it. You will live history the way it was. We guarantee it.

The almost evangelical fervor with which a past relived without scripts is pursued here reminds me of Mary Douglas's theory that such sentiments are often generated in high-grid, low-group, egocentric societies, the societies of "impersonal rules."[20] Ritual is disdained by those who feel excluded in such societies in favor of direct communication—communication without symbols—with what is sacred and more real, more "authentic." Rhys Isaac noted this also, as discussed in a previous chapter, in

regard to the transformation of Virginia society during the period 1740 to 1790.[21] There was a change in that society from ritual to spontaneity, from hierarchy to egalitarianism, from hospitality to individualism, and from conviviality to privatization. This serves as well as a description of the iconic values of America, values especially related to the American West. Out here on the "frontier" there is disdain for formality, for bureaucracy, for anything, in fact, that limits a person's freedom to do as he or she damn well pleases. Many National Park Service employees who have worked in the "last" American frontier, Alaska, have told me that they were afraid to let people there know that they worked for the federal government. There were stories of nasty, sometimes violent, incidents. Alaskans went north to get away from things like federal governments: governments impose licensing requirements for fishing and hunting, environmental regulations, and restrictions on the use of marijuana.

As I talk to Jack Wise, it occurs to me, not for the first time, that the ethos at work here is very, much like that of the Plains Indian:

The endurance, courage, independence, perseverance, and passionate willfulness in which the vision quest practices the Plains Indian are the same flamboyant virtues by which he attempts to live: while achieving a sense of revelation he stabilizes a sense of direction.[22]

I would venture to say that Geertz has presented here a list of the qualifies that many in America, if not the rest of the modern world, admire most. They are certainly regarded as virtues in the nearby town of La Junta, Colorado, home of the "world-famous" Koshare Indian Dancers (fig. 24). None of the dancers is really Indian. The organization is a Boy Scout Troop. It is much less of an exaggeration to say that the Koshares are world famous. They have danced all over the world and are much in demand wherever the Boy Scouts or similar organizations gather. The Koshares were organized by Buck Burshears, a local man who died several years ago. He was alive when I did my excavations of the Bent's Old Fort trash dumps in 1976, and we had the opportunity to talk several times because he was very interested in what we were finding at the fort. I remember most his conviction that admittance to the Koshares practically ensured a boy's success later in life. Buck could talk at great length about his boys who had become doctors, lawyers, and successful businessmen. In part he attributed these success stories to the discipline it required to be a member of the dancers, but he also felt that the young men were absorbing some of the admirable traits of the Indians: independence, determination, and stoicism.

Figure 24.

Cover of the Koshare Dancers' souvenir publication.

In drawing a distinction here between the National Park Service and non-National Park Service approach to interpretation, I do not mean to say that Park Service personnel are immune to the allure of evangelicalism. Recall that the regional director chose to play the role of the independent, free, and spontaneous trapper instead of the wealthier and more powerful trader. And Don Hill has spent a good deal of time searching through military records for references to his Claremont County, Ohio, ancestors who fought in the Mexican War. He eventually discovered that they had gone through Veracruz, but not Bent's Old Fort. He was disappointed because, as he tells me on Independence Day, he was hoping for the sense of "connection" he understands many of his reenactors to be seeking.

And so while a National Park Service employee such as Alexandra Aldred, Bent's Old Fort's chief of the division of interpretation and resource management, might approach reenactment in a more ordered way than does Jack Wise, it is still with a good deal of passion. Alexandra has worked for the Park Service at Bent's Old Fort since 1968, and a conversation with her soon reveals the qualities—organization, initiative, an innovative approach, and determination—that have moved her from an administrative assistant position (which she held when I was conducting excavations at the trash dumps) to her current job, which is second in authority only to that of the superintendent. In 1976 she was generally known by the Americanized "Alex"; today she gently encourages me to call her Alexandra, pronouncing her name in the Hispanic fashion with softened consonants.

Alexandra shares some statistics with me from the 1991 statement for interpretation. In 1990, visitors were largely families and couples traveling at least overnight and were likely to be relatively well educated and secure financially. A full 65 percent were "through visitors," whereas only 35 percent were "home based" (had departed from and were returning to their homes in the same day). A reported 55 percent of visitors were with family groups, and 17 percent were couples without children. Only 14 percent were local residents (and this counts the busloads of children from local schools), 35 percent were regional residents, 48 percent national residents, and 3 percent international residents. There is a great interest in the site among the German and Japanese visitors, but to get to Bent's Old Fort requires a special effort because it is slightly off direct routes between other major tourist attractions. Only 3 percent of visitors were members of minority groups.

Taking into consideration the composition of her audience, Alexandra is particularly interested in portraying the roles of minority groups in the history of the fort through the interpretive program. She thinks that the living history and reenactment programs convey minority participation in the historic activities at the fort very well. Alexandra explains that the initial interpretive emphasis at the fort on the hunters and trappers, the "mountain men," was a bit misleading since by 1846, the year to which the fort has been reconstructed, these mountain men were no longer frequenting the fort as much. This initial emphasis had been evidence of the powerful link that existed in the thinking of many of the "publics" between the fort and mountain men. There seemed to be some compelling symbolism here. Mountain men—the trappers—perhaps more than any other group held a liminal position between the American and the Native American. Through their intimate association with Native Americans (so we are told by both contemporary and current-day popular accounts), the mountain men acquired some of the Native Americans' most remarkable characteristics: toughness, resourcefulness, disdain for authority, and the ability to survive in the wilderness on their own.

Interpretation is now, however, more carefully based upon research into what transpired here at particular times. This shift in the interpretive focus came as a relief to the park staff, Alexandra tells me. Mountain men reenactments could easily get out of hand. There was a good deal of the drinking and carousing that reenactors associated with the behavior of the mountain men. The reenactors insisted upon the same kind of freedom and absence of societal controls they ascribed to the mountain men.

The Independence Day events—breaking the piñ, firing the cannon, making adobe bricks, cooking food in the plaza, reading the Declaration of Independence, the presence of dragoon and Indian encampments, and so forth—were based upon observations made firsthand by historic visitors to the fort on various Fourths of July. Alexandra discovered all these events in the copies of diaries and notes kept in the fort's library. She worked from the observations of Lieutenant Abert, Susan Magoffin, and Alexander Barclay.

Alexandra is especially pleased because this year, for the first time, a local African-American woman, Phyllis Howard, had agreed to play the fort's famous black cook, Charlotte. Alexandra had tried repeatedly over the years to fill this position by contacting black universities in the South, to no avail.

There have been similar problems in filling the "roles" of Native Amer-

icans and Mexicans for living history and reenactment purposes. Recruiting from the list of potential employees provided by the regional administrative office, the "seasonal register," had not yielded a diverse pool of applicants. Seasonal applicants are allowed to select two parks at which the), would like to work, and those choosing Bent's Old Fort were most likely to be white males. The park has been successful in recruiting for Native Americans on only a few occasions. Each time the recruits were unhappy with being separated from their family groups and went back to the reservations in Oklahoma after a short period. Native Americans at Bent's Old Fort fur trade reenactments are frequently portrayed by Anglos, very talented and dedicated, who bring with them tipis, costumes, cooking equipment, weapons, and other Native American accoutrement they have carefully constructed. Over long reenactment weekends, they will sleep in their tipis down by the river, cooking and living as their careful research indicates that Native Americans did. Meanwhile, real Cheyenne who sometimes come from the Oklahoma reservations to participate in these weekend reenactments usually stay at one of the local motels. Nonetheless, Alexandra never ceases in her attempts to get representatives from appropriate ethnic groups. For the Independence Day observance, she had found a Mexican migrant family from Brownsville, Texas, who were American citizens. Unfortunately, one of the children in the family became ill at the last moment.

Craig Moore, a member of the permanent interpretive staff at the fort, has developed over many years very close ties with the Southern Cheyenne on the Oklahoma reservations. In the spring of 1991, he persuaded the Henry Whiteshield family to come to the fort, where they reenacted the typical manner of ritual exchange in the trade rooms. This proved to be a very moving experience for Craig and many of the interpretive staff, to whom the ritual significance of the reenacted exchange was clear. Henry, gray-haired and distinguished, told me he found it satisfying to be at the fort, and he was gratified at the respect displayed by the visitors who observed the reenacted ceremony.

For the 1992 Independence Day celebration, Craig arranged for the presence of Ann Shadlow and her daughter, Mickey Pratt. Both these women have been very active in the movement to preserve Cheyenne traditions. Ann Shadlow is a storyteller and recipient of the Native American Woman of the Year Award. Her grandmother was Julia Bent, youngest child of William Bent and Owl Woman. Because Julia was present at the Sand Creek Massacre, she, like her brothers Charlie and George, gave up

the white lifestyle that William had tried to encourage them to adopt. Julia married another offspring of an Anglo-Cheyenne union, Edward Guerrier, son of famous mountain man Bill Guerrier. Ann lived with Julia from infancy, and Julia attempted to provide Ann with a traditional upbringing, to the extent of never speaking English or permitting it to be spoken in Ann's presence. She also taught Ann as many as possible of the Cheyenne stories, some of them quite likely thousands of years old. Having told the stories to Cheyenne children virtually all of her life, Ann several years ago responded to what she had by then decided to be the sincere interest on the part of non-Cheyenne and attended the National Folk Life Festival in Washington, D.C. This led to a number of engagements all over the country. At the Independence Day observation, she for the first time told a story in Cheyenne to a white audience.

To Alexandra the fort and grounds are a teaching tool, one that is particularly vital because she has learned that what one experiences is retained much longer and in much greater detail than what one merely hears or sees. Her approach to interpretation was greatly influenced, she says, by a visit to Mount Vernon in the 1950s. She was herded through the home of George Washington in an unpleasant way, and she felt that she had learned nothing. It was as if she were expected to feel privileged to have been permitted to enter such hallowed ground. The opportunity to experience the massiveness of the fort itself is important, she thinks. Alexandra had been at the site for six years prior to reconstruction, looking almost every day at the foundations there. Nonetheless, she was astounded by the scale of the fort as the walls began to rise.

She admits that the reconstruction raises some difficult ethical questions. The week before my conversation with her, interpretive specialists from the Harpers Ferry Center had been on site and had followed her and some of her interpreters around for several days as they gave tours. One of the observations the specialists found most remarkable was the number of times people would ask if the fort were real—dating from the previous century, that is. Several different members of the same group of ten to twenty visitors might ask this question in the course of a single tour. The visitors evidently found it very difficult to accept that the fort was a reconstruction. Alexandra feels sure that many people leave the site still believing that the fort is historic fabric, even though she tells the groups at the beginning of the tour and sometimes several times more in the course of the tour that the fort has been reconstructed, that it is all new, with the exception of some hearth stones in the kitchen.