Epilogue

Modern Ritual at Bent's Old Fort

Ideology and Ritual

Modern man draws a line between religion and ideology, but that line is revealed as a fuzzy one if carefully examined. At first, unreflective glance, the difference seems clear enough. Religion assumes the intervention of supernatural forces in the world, while ideology must make its case for the order of things without recourse to the supernatural. After a more sustained look at the matter, we might notice that those who subscribe to an ideology, tend to behave as if supernatural or, at least, sacred forces were at work in the world. Often they seem to be striving for the attainment of some sort of earthly paradise and to regard their lives as meaningful only insofar as they are contributing to that end.

After all, what is regarded as supernatural depends upon one's definition of the natural. In previous chapters I have argued that such notions are socially constructed. "Natural law" often serves as a paradisiacal model. It is what the world was like before the connection between heaven and earth was sundered. The natural order would again be realized if all would behave correctly. A model for correct behavior was provided by the gods and the ancestors—in the case of ideology, one may regard the founders of countries, business or social organizations, schools of thought, movements in art, or countercultures as the gods and ancestors. Present-day leaders are those who most closely emulate such behavior. Human neoteny provides the basis for ancestor veneration and plays a large role in the selection of leaders and our attitudes toward them. The ancestors and gods, as well as present-day leaders, share many attributes with the

primary caregivers we knew as children. They tend to appear to be larger, more powerful, and more knowledgeable about the arcane than are we.

Whatever the differences between religion and ideology, they are structured similarly. They are socially constructed models of the ideal. As such, they provide the basis for value and belief systems that motivate the behaviors of individuals and groups. In this way (among others) they are different from theology and philosophy, which deal with the intricacies of value and belief systems themselves. Religion and ideology are in this sense more practical, and theology and philosophy more abstract. As Geertz said of religion, and I think the statement applies as well to ideology, it is the "placing of proximate acts in ultimate contexts."[1]

What I have been arguing for, while describing the history, ethnohistory, and material culture associated with Bent's Old Fort, is the recognition of a means by which both religion and ideology are shaped and propagated that is most essentially nonverbal. I have called this ritual, or fugitive ritual, the means by which the proximate and mundane is imbued with the sacred or sublime, and placed within an ultimate context. Ritual is inseparable from either religion or ideology: Religion and ideology are what we do, while theology and philosophy are what we think about what we do.

I have been arguing even more specifically that ritual was a crucial factor in the "winning" of New Mexico and the Southwest. As a part of doing so, I have tried to illustrate the essential aspects of ritual as they occur in both religious (traditional) and ideological (modern) societies. All ritual shares the basic structure of the Sun Dance, in that it refers to an ideal pattern that provides the model for the current social configuration and one's place within it. As we have seen, rituals are liminal. They persist precisely because there must be some means by which to adjust for the tension between the ideal and the world at hand. The ideal, the unchanging, sometimes must change because it becomes drastically out of tune with contemporary conditions and possibilities. More frequently, one's status in reference to the ideal changes. Both sorts of transitions are accommodated, and facilitated, ritually.

Clifford Geertz's view of ideology was that it provides a symbolic framework to replace the one lost as parochial religious symbolic structures are discarded. Such religiously based structures are abandoned as the world becomes less parochial, and religious symbolism can no longer accommodate the phenomena observed in the larger world. Sense is made of the world, after all, by matching up internalized symbolic structures with external experience. These structures may be thought of as a variety

of Kant's a priori assumptions. Making sense of the world by means of these assumptions is the first order of business for humans. If such sense cannot be made, anxiety is generated that precludes effective behavior. Anxiety of this sort is unbearable and explains the mad scramble for a workable ideology that Geertz described as occurring in modernizing countries. He gave as an example the French Revolution, which he said was, "at least up to its time, the greatest incubator of extremist ideologies . . . in human history."[2]

There is an urgency here, an intensity that is entirely understandable from a Kantian point of view, a viewpoint more lately called phenomenological. The intensity is acknowledged in both popular and scholarly attitudes toward ideology. To call someone an ideologue, for example, is not to be flattering. It implies that the person is close-minded, that he or she is willfully nonreflective. Such a person clings to his or her beliefs desperately since to lose them, he or she fears, would produce unendurable chaos in his or her life. For similar reasons, any change in the ideology to which he or she subscribes is feared and resisted. The person or group and the events associated with the origin of the ideology assume almost sacred status. Here is one area, as I have discussed just above, in which the line between religion and ideology becomes very blurred.

Freud and Marx, for example, are often regarded as kinds of demigods, beings touched by the infallibility of genius (itself a word with supernatural overtones). Their followers occupy a kind of privileged position and are permitted insights denied to others. Thus, for example, Marxist thought emphasized that ideology obfuscates and prevents an understanding of true social conditions, particularly power relationships between socioeconomic groups. Marxism itself, however, is not recognized as an ideology by Marxists. As Mark Leone explained in his "Time in American Archaeology": "Ideology in the Marxist sense simply does not exist in societies without classes."[3] Geertz commented in a tongue-in-cheek manner, "I have a social philosophy; you have political opinions; he has an ideology."[4]

Similarly, Freudians believe they alone see the world without illusion. Eric Berne, author of enormously popular books based in Freudian psychology (among them I'm O.K.—You're O.K.) said in a recent book that

the human race is split during late childhood into the Life Crowd, who spend their lives waiting for Santa Claus, and the Death Crowd, who will spend their lives waiting for Death. These are the basic illusions on which all scripts are based.[5]

This statement prompts this question: If half of the human race believes in one sort of illusion and the other half another, who is illusion-free? Only the Freudian analyst . . . and his patients (who, it is important to note, look upon the analyst as a surrogate parent):

The therapist, with full humanity and poignancy, and with the patient's explicit and voluntary consent, may have to perform . . . surgery. In order for the patient to get better, his illusions, upon which his whole life is based, must be undermined. . .. This is the most painful task the script analyst has to perform: to tell his patients that there is no Santa Claus.[6]

If the "surgery" is completely successful, the patient will achieve a kind of modern nirvana, known among some psychologists and a large portion of the general public as "self-actualization."

These points do not refute self-actualization, nirvana, or the cultural awareness required to see behind the masks of capitalist ideology as ideal conditions to which humanity might aspire, but they should be seen as just that. And what this highlights is that the enterprise of pursuing ideal states, even of the modern sorts, is inextricably bound up with ritual. The patient emulates the analyst (the embodiment of the ancestors), the spiritual novice the sage, the student the Marxist teacher. Because human enterprise (Freudian, spiritual, Marxist, and in general) is entangled with neoteny, there is a tendency to see "our" small group (the surrogate family of origin) as the only one that has access to ultimate knowledge, and one which must battle "their" much larger and potentially overwhelming group that would, if they could, snuff out the flickering flame of truth.

Neoteny in this way colors our perception of all human transactions, even perceptions informed by scholarship. The concept of cultural hegemony was offered by the Marxist Antonio Gramsci to explain how a culture can dominate other cultures or sub-cultures without recourse to overt coercion.[7] Because it assigns central importance to values and beliefs, cultural hegemony might be used as a key to an enhanced understanding of the events and, especially, the material culture associated with Bent’s Old Fort; it might explain how the "hearts and minds" of the members of he various cultures of the Southwest were won, and thus how Kearny's Army was able to walk virtually unopposed into Santa Fe. Cultural hegemony could enable the construction of an appealing story for Bent’s Old Fort (and elsewhere) with clear-cut heroes and villains all acting according to ideological scripts with which we, from hearing similar stories, are familiar. Nonetheless, such stories ignore problems of motivation and intentionality that a phenomenological approach finds quite relevant to an under-

standing of collective human behavior. Characters in dramas scripted in accord with cultural hegemony theory are either battling or in league with a diabolical force. The complexities of making real life decisions in the context of competing and conflicting value and belief systems are not well represented in these tales.

To begin with what is a relatively minor point, the Bents and Ceran St. Vrain were not intentionally advancing modem ideology. They were extraordinarily skilled socially. They demonstrated a high level of competency for communicating well, verbally and nonverbally—nonverbal communication including ritual. They honed and exercised these skills to advance their own interests, financial and otherwise, which to some extent coincided with the interests of other groups, including businessmen, and politicians in the East. That these interests were not compatible in the end with their own is evidenced by the demise of Bent & St. Vrain Company, the death of Charles Bent, and the tragedies that befell William Bent and his children. By the end of the fur-trading era, William Bent's interests coincided as much with those of the Cheyenne as with any other group.

More important, by the cultural hegemony model, the Cheyenne and the Mexicans, as well as the principals of Bent & St. Vrain, would be seen as dupes: they were "co-opted," and they sold out for the industrial goods of the Western world. I would say, rather, that they became engaged in a modernization process that began in Europe, reached the Southwest in earnest in the early nineteenth century, and is still occurring in most parts of the globe. Faced with the unavoidable impingement of the modem world, the Cheyenne and the Mexicans replaced at least some of their traditional and more parochial symbolic system with elements of the ideology that was proffered to them by means of the Bents, their fort, and the exchange of trade goods. The rituals involved were, after all, those of inclusion. At a liminal moment in their history, the rituals eased a transformation that most had chosen. This is what ritual is supposed to do, no less in this case than when a Sun Dancer seeks a new vision for a reformed life. As to being dupes—well, there are advantages to modernity, after all. And though the Cheyenne were undone, it was neither the rituals nor modernity, per se, that were their undoing. Tragedy occurred when ritual ceased.

I hasten to make two additional points. I am not saying that the annexation of the Southwest was done for purely ideological purposes or by completely ideological means.[8] Ideology is never pure—it is interwoven with all other strands of culture. The political and economic situation in North America in the early nineteenth century was more complex

than I have been able to deal with fully in this book. I have mentioned almost not at all the happenings in Texas, for example, or California. Nor have I dwelled much on the threats, perceived and real, from other European powers who might have had designs on parts of North America and how the Mexican War was in part a reaction to that. David M. Pletcher has observed that:

If the United States had not won the [Mexican] war decisively, the power of Britain and France might have increased in the Atlantic and the Caribbean. Thus, the war was a ruining point, not only in the internal history of the United States and in its relations with Latin America but also in the relations between hemispheres. Victory in the Mexican War did not launch the United States as a Great Power—this would require another half-century of growth—but it certainly helped to promote the nation from a third-rate to a second-rate power that would have to be reckoned with in its own neighborhood.[9]

The United States had economic and political motives, which were advanced through political and military means. The standard presentation of history, however, leaves out the role of value and belief systems (in this case, ideology) in both setting and achieving such agendas. I am saying that our understanding of history, is deficient without a fuller appreciation of how value and belief systems operate in these regards.

My second point is that I am not offering an excuse or apology for the military invasion of Mexico. Quite aside from questions about the morality of the Mexican War, resistance to the American presence in and then its annexation of the Southwest was minimal. Had there been resistance, it seems doubtful that New Mexico, at any rate, would have been won and held.

What transpired after the war, I think, strengthens the case being presented in this book for the importance of ritual in the construction and maintenance of what Richard White has termed a "middle ground," and which I regard as a common world.[10] A resistance or separatist movement did not develop among the New Mexicans. Among the Native Americans it did. The reason for the difference in reaction had to do with more than just economics. The federal government expressed its willingness to support the Cheyenne and other Plains tribes if they would abide by a new set of rules. But life under these terms was meaningless. The new life being proposed was so far outside of the symbolic framework that had organized their lives that it evidently made little sense to the Cheyenne.

It is important to remember, too, that the symbolic structure being used by the Cheyenne was not developed by the Cheyenne and other tribes

in isolation. Although it contained ancient elements, it had been shaped in large part by interactions with the Europeans since they intruded upon the continent three hundred years earlier. The Plains Indians' culture often seems strangely familiar to Americans of all sorts, including Anglos, because Americans and the Plains Indians created it together. During its creation, the Plains Indians were partners with the newcomers from the Old World. The traders respected Native American traditions, participated in Native American rituals, and, in so doing, gradually transformed the Native American culture. We have seen, for example, how the Plains Indians thoroughly adopted individualism.

With the end of the fur trade, the opportunity to live in meaningful ways was suddenly removed. Meaningful behavior for Native Americans was reenactment of ideal behavior, the behavior of the ancestors and gods. The Native American perception of such primordial behavior, however, had been shaped by three hundred years of ritual trade with the Europeans. The "traditional" preoccupation with buffalo hunting and raiding had developed in tandem with European and then American interests in the West and Southwest and had found its fullest expression in the relationship between the Cheyenne and Arapaho and the Bent & St. Vrain Company. Without trade, the connection—the ritual exchange—that linked the traditional realm of meaning with the new one was also taken away. From a traditional point of view, the cessation of opportunities for Plains Indians to participate meaningfully in exchange with their White Father constituted a betrayal.

New Mexicans, on the other hand, were not deprived of their traditional activities, nor were their connections with the modern world, based in ritualized exchange, severed. Not only did they remain involved with the Santa Fe Trade, for instance, but their involvement increased just prior to and after the war in a number of ways. David J. Sandoval has estimated that half of the goods moving over the Santa Fe Trail in 1838 were being transported by Mexicans.[11] Other scholarship in progress presents similar business enterprises on the Chihuahua Trail at about the same time.[12] By the time of the Mexican War, many Hispanics were mercantile traders as well. Their more complete acceptance of modern ideology rendered these activities meaningful in their culture. Acceptance of a wider spectrum of modern beliefs and values came quite readily to the emerging middle class in New Mexico, perhaps because they could emulate the traditional behaviors of the elite in their society in regard to mercantile trade.

This argument is the one central to this book: Bent's Old Fort served as a model of modern ideology, and that ideology, or essential portions

of it, was then propagated in a ritualistic manner to the more traditional cultures of the Southwest. More of this ideology was adopted by the New Mexicans than by the Native Americans, in part because ritual interaction between the Americans, who were bearing the new ideology to the Southwest, and the New Mexicans was sustained after the Mexican War. Ritual exchange between Americans and Plains Indians decreased drastically after the abandonment of Bent’s Old Fort and virtually ceased after Sand Creek. One effect of this was that the Native Americans became anomalous figures in the modern world.

Bent’s Old Fort, reconstructed in 1976, operates again today as "ritual ground." In investigating present-day ritual, we have the advantage of being able to observe it firsthand, which allows us to identify some fine points in the operation of ritual that are often lost to historic and ethnographic accounts, as well as to the archaeological record. Treating these fine points constitutes a step along the road suggested by Geertz, toward a reasoned examination of symbolic frameworks—to my way of thinking, these frameworks are rituals. Such examination might lead to the more informed application of ritual. Ritual is inevitable because it is a part of the social structure by which essential cultural meanings are conveyed, manipulated, and altered. A society devoid of ritual is impossible because ritual establishes the connections among individuals, and groups, that are necessary, to a society. The question is only how ritual will be employed.

In what follows, I direct the reader's particular attention to two aspects of ritual at the restored fort, which is now known as Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site. The first is the tendency in a modern high-grid, low-group, ego-centered society. such as our own for the development of what has been called an "evangelical" faction by Rhys Isaac.[13] This faction is one that, Mary Douglas says, "discards existing rituals and looks for a radical new rite which will usher in a golden era."[14] At Bent’s Old Fort, this faction comprises the employees of the history association that is affiliated with the park and some of the volunteer interpreters. Evangelicals, as the name implies, seek direct access to communion with the primordial past, whether the ideal or the sacred, depending upon how one looks at it. They believe that existing, formal structures of ritual impede immediate access, and they do not acknowledge their own behavior as ritualistic. The other ritualistic phenomenon I address is the way interpretation, obviously a kind of reenactment, is being used in an attempt to reform society. There is a very. conscious effort to "write in" to the "script" the activities of minorities. The reformation is being attempted by minority employees of the National Park Service, with encouragement from the agency itself.

Independence Day

Jack Wise is selling a great many beads. In the reconstructed storeroom of Bent's Old Fort, he chats with the visitors, explaining the historic uses of the trade goods displayed on the walls and selling handsome reproductions of trade items as fast as can be done without disrupting his narrative. It is Independence Day in 1992, 143 years after the fort's proprietor, William Bent, abandoned and destroyed the massive adobe structure. Whether this was done intentionally or unintentionally is a matter of speculation and debate among the interpretive staff here. The Fourth of July was a grand event during the fort's occupation, perhaps the biggest of the year in that era of patriotism and optimism. Appropriately, this will be the busiest weekend of 1992 for visitation, and the entire arsenal of interpretive approaches is being employed.

Reenactments of certain historic events that occurred here are under way. Ann Shadlow, the great-granddaughter of William Bent and his first Cheyenne wife, Owl Woman, is telling stories to groups of tourists in the tipi just outside the fort's front entrance. Ann is also the granddaughter of Julia Bent and Edmund Guerrier, both half-breeds who survived the Sand Creek Massacre. In fact, she was brought up by Julia Bent, who, having abandoned the ways of the whites because of Sand Creek, taught her no English. Ann spoke only Cheyenne until she was twelve. Nearby, on the banks of the Arkansas, tents have been pitched by reenactors portraying the advance guard of General Kearny's dragoons. In 1846 these dragoons and other troops massed three or four miles downstream from the fort, shoeing oxen and picking up fresh supplies preparatory. to their invasion of Mexico. General Kearny and his officers meanwhile received intelligence information from and discussed strategy with the owners of the fort and prominent Santa Fe traders, probably in the dining and billiard rooms of the fort.

Another encampment by the river is that of a Mormon woman and her children. The Mormon woman speaking "in character" tells you that she and her family were displaced from Missouri by the infamous Extermination Edict of Governor Lilburn Boggs. It is somewhat ironic that a Mormon family would seek refuge at Bent's Old Fort, since Governor Boggs had been married to Juliannah Bent, younger sister of William and Charles Bent. Juliannah died after bearing two children by the governor, but he still retained close ties to the Bent family. The Mormon woman says that her husband has taken ill from the journey, probably from the

water in one of the streams along the Santa Fe Trail. He is seeing the doctor inside the fort.

Out of character, she will tell you that she is not permitted in the fort became evidence that Mormon women were at the fort is inconclusive. Her real-life husband is even now, between his stints at portraying the doctor's patient, searching through the reconstructed fort's modem library for the evidence that he hopes will someday gain entrance for his wife to the fort during one of these reenactments. They are Mormons in their daily lives, and it is important to them that their church be written into this piece of history.

The man in charge of the administration of all the National Parks in the Rocky Mountain Region, Regional Director Bob Baker, has chosen to spend this Fourth of July weekend at the fort. He and his wife are dressed in period clothing, which, like most of the period dress worn at the fort today, was made four years ago. The design and manufacture of clothing that might have been seen at the historic fort, down to the manner in which it was stitched, was the object of careful research. The clothing being worn now by the superintendent of the fort, Donald Hill, for example, was patterned after the jacket, shirt, and pants taken from the body of a free trader who died in the early nineteenth century. That the superintendent is dressed in the clothing of a free trader, who occupied the uppermost rung in the hierarchy of the fort, seems logical. Bob Baker, though, is wearing the outfit of a trapper. Don Hill tells me later that he had made the offer of trader's apparel, but Bob had been very sure that he wanted to portray a trapper instead. To my wondering aloud about why the regional director would find the role of a trapper more appealing, Don replies that the trapper symbolizes the romance of the era to many. Perhaps the regional director identifies with the independence, freedom, and self-sufficiency of the trapper, he says.

Outspoken and highly animated, Bob Baker earlier this morning told the assembled park staff that their most important task was to impart to the public a sense of what the park should mean to them. The Park Service must touch the visitors' hearts with the story each particular park has to tell. At the conclusion of his talk, Bob had played a videotape his office had produced in which the images are accompanied by a popular song, a kind of rock ballad. The videotape is filled with symbols: small children, handicapped National Park Service employees, beautiful views of national parks, and park visitors of all races. I am moved, and then a bit embarrassed to be so. Nonetheless, I consider asking for a copy of the videotape to show to my own office.

After the meeting adjourns, Bob Baker walks the parapets and bastions of the fort, appearing unexpectedly, like Banquo's ghost: now here to watch the reading of the Declaration of Independence in the plaza, now there to observe an interpreter describe the diversions in the billiard room. The superintendent, despite his trader's clothing, has been thrown into the real-life part of Macbeth: his ambitions for his site are imperfectly concealed as he engages the regional director in frequent quiet but intense conversations.

The panoptic mechanism is still at work here, quite obviously, as it was over 140 years ago. The architecture of the fort still serves admirably in this regard. A dignitary, the regional director, has arrived to inspect the operation. If not quite at a glance, he can quickly observe the interpretive program from any number of positions on the second story of the structure, particularly from the bastions and watchtower. He watches the exhibition of bullet making in the plaza, the Cheyenne tipis out in front of the fort, the dragoon camp down by the river, and so on.

Other rituals that support hierarchical divisions, in addition to the inspection itself, are also in place. The regional director will eat at first table with the superintendent and senior park staff. Were there no reenactment, he would probably have lunch with them anyway. It is an eerily reflexive situation: the historical roles the regional director and his staff are playing out are something like their present-day roles. What strikes me as especially strange, as a fellow employee of the National Park Service, is just how natural these roles appear to me.

Ritual and Interpretation

Independence Day conforms in virtually every way to what one would expect as a ritual on the summer solstice. July the Fourth, after all, is only a few days after the actual solstice and probably represents the limits to which historical fact could be stretched in the direction of that precise date. Were the celebration to occur on the actual solstice date, the night would be the shortest of the year. It is, therefore, a liminal event, marking the transition from a period during which days grow longer, to the sixth-month period when they will grow shorter. From the traditional point of view, danger is always present at times of change. Fireworks, an Independence Day tradition, have been used in many places to frighten away demons on such occasions. The fact that Independence Day is

thought of as a secular holiday only illustrates that the modern distinction between ideological and formally religious phenomena, while obviously useful, is also misleading insofar as the workings of ritual as a social mechanism are concerned. As Anthony Giddens has observed in regard to one of Emile Durkheim's most noted works, "The Elementary Forms demonstrates that the existence of gods is not essential to religious phenomena."[15] With this in mind, we should not be surprised at the various sorts of portrayals of the ancestors (the founding fathers) and the retelling of the origin myth (the reading of the Declaration of Independence and related documents) that are presented in parades and speeches on July 4. At Bent's Old Fort on July 4, 1992, the Declaration of Independence is read in the plaza—as it would have been during the fort's occupation.

Every day at Bent's Old Fort is an Independence Day of sorts, a reenactment of the consecration of the Southwest by its inclusion in the United States. Ritual must replicate the primordial behaviors of the ancestors (or gods) who created the order of the world out of chaos. This activity refers to a mythology, which may be subtly changed by the manner in which the ritual is enacted. The ritual must evoke an affective response; that is, it must induce the "sentiment" that promotes the internalization of the values and beliefs expressed by the ritual and the mythology As the regional director observed, the ritual must "touch the heart," in this case with the "story each park has to tell," in order to serve the public.

Ritual is transacted only in part by words. Some ritual employs no words at all. Nonverbal aspects of the interpretation can be more convincing than verbal presentations, because they appear natural and obvious, and because they are not explicit and, so, are difficult to explicitly discuss or refute. The architecture, landscape, and furnishing of an historic site like Bent's Old Fort are obvious examples of this. Even absences are meaningful here. The dirt, the bad smells, the noise, the illness, the danger and uncertainty, and the coarseness and brutality are not well presented, if at all. There are valid reasons for not replicating such conditions in the present day, but leaving them unrepresented panders to the nostalgia for a lost paradise that is ubiquitous among human populations.

Verbal, ordered, rational, that is to say, elaborated presentations of historic context can help here, but even these have ritual components. In the case of national parks, elaborated presentations are bolstered by ritual in two notable ways. First, the authority of the verbal presentation is enhanced because it is the "official" history. Here again, what is left out of the official history might be assumed by the visitor to have not existed. Second, a political—which is as much to say ritualistic—process is used

Figure 22.

Dedication of the marker erected by the Daughters of the

American Revolution at the site of Bent's Old Fort. (Courtesy Colorado

Historical Society, Denver.)

in designating areas as part of the National Park System. I will deal with the second of these two components, then take a closer look at the notion of "official" history.

William Bent abandoned and partially destroyed the fort in 1849. There is no record of its use for the next thirteen years. From 1861 until 1881, the somewhat restored structure was used by the Barlow-Sanderson Overland Mail and Express Company as a home station and general repair shop. Then, for the next three years, many of the rooms were used for cattle stables. After 1884, the fort was unoccupied. The adobe, without constant repair, deteriorated rapidly.

The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) dedicated an historic marker at the Bent's Old Fort ruins as early as 1912 (fig. 22). The ceremony drew over two hundred people. Local dignitaries posed for photographs next to the marker and atop a "genuine Overland stagecoach." In 1920, the DAR took over the site and, in 1930, erected a cobblestone gateway arch at a cost of $319.32, "to which . . . schoolchildren, among others, contributed" (as reported in the 1963 DAR "Golden Anniversary Program").[16] Thereafter, the fort was the site of reenactments, plays, and celebrations. By 1954, the financial burden of maintaining the remains of

the fort and the grounds had proven heavy enough so that the DAR cheerfully conveyed the deed to the fort property to the State of Colorado for the sum of one dollar. The State Historical Society of Colorado, seeing in the fort potential for emphasizing Colorado's role in American history, began its lobbying effort for federal sponsorship of the site almost immediately. Politicians receptive to this idea included Governor Daniel Thorton, both Colorado Senators, John A. Carroll and Gordon Alott, and Congressman J. Edgar Chenoweth of the Colorado Third District. Particularly effective in enlisting the assistance of these politicians was Dr. LeRoy R. Hafen, the executive director of the State Historical Society.[17]

In February 1958, Acting National Park Service Director Eivind Scoyen advised Colorado Senator Carroll that Bent's Old Fort would fit well within that year's priority theme, Westward Expansion. Scoyen then authorized the preliminary historical and archaeological investigations at the fort that marked the beginning of federal efforts that would culminate in the reconstruction of the fort. Two years later, in 1960, President Eisenhower signed a bill that became Public Law 86-487 of the 86th Congress, "authorizing the establishment of a national historic site at Bent's Old Fort near La Junta, Colorado."[18] The reconstruction was funded so as to be completed by the American Bicentennial, in 1976. At the dedication ceremony that year were U.S. government officials, the governor of Colorado, Native American groups, and mountain men reenactors.

All of the actions that led in 1960 to the fort's designation as a National Historic Site were predicated upon the idea that Bent's Old Fort was a site of premier historical significance to the United States. It, thus, became a part of the nation's official history. This lends authority to the interpretation provided, both verbally and nonverbally, at the site. But what, exactly, do these notions of "significance" and "official history" entail?

Robert Berkhofer has been a leader in the reevaluation of history as it is practiced by the historian; that is, he has striven to make the historian visible in the creation of history, a stance that he argued is more instructive than assuming that objectively significant historic phenomena are waiting somewhere to be discovered. This latter assumption is basic to what Berkhofer termed "normal" history. Berkhofer pointed out that "normal" history is based upon two assumptions: a "Great Story," which is formed according to standard structures and themes, and a "Great Past," which is composed from the Great Story.[19] Clearly, Bent's Old Fort was judged significant because it conformed to a Great Story, identified by the National Park Service and the Congress of the United States as "Westward Expansion." This Great Story is a history that is increasingly out of

touch with an ever more pluralistic society (one that does not necessarily, reflect social fragmentation or balkanization but, more probably; an ever less parochial world).

When Bent's Old Fort became a part of the "official" history of the United States, it became a part also of its Great Past. The United States, however, had changed dramatically in the years between 1960 and 1976, the date of the dedication of the reconstructed site. What may have been conceived by its early sponsors to be a bit of unalloyed celebratory history—the expansion of the United States into what had been Mexican Territory—held other connotations by the early, 1970s. Several revisionist history books had been published that compared the Mexican War to the war in Vietnam. Concepts like "Manifest Destiny," had become anathema to a large section of the United States population in the 1960s, particularly in academia, and sensitivity to the mistreatment of Native Americans at the hands of the United States government was growing. Such mistreatment was obviously relevant at the new historic site given the intimate relationship between Plains Indian history—including the Sand Creek Massacre and the removal of the tribes to reservations—and the story of Bent's Old Fort. Also, the notion of Westward Expansion did not strongly suggest the role of minority groups in Southwestern history, and Hispanics were by the 1970s the fastest growing minority group in the country.

In employing the terms Great Story and Great Past , Berkhofer identified history as the operant mythology of the modern world (although he may not have intended to do precisely this). While modernity assumes objectivity, Berkhofer and other postmodern or poststructuralist scholars have argued convincingly that objectivity in the realm of human events does not exist. They urge a perspective, in this way, that challenges modern ideology.

We see the mythologizing of the past more clearly in our accustomed role as observers to "primitive" societies. These societies, we assume, have less concern with what "actually happened." In such societies, stories arc told as a part of a larger ritual re-creation of the world. The Australian Aborigine "sings" the world into existence by retelling the origin myths. If he did not, he believes that the world would come to an end. In a similar way, telling and retelling our modern histories assures that the modern world is renewed and the existing order legitimated. On some level, which we try hard to ignore, we understand as well as do the aboriginal inhabitants of Australia that without the constant retelling, the world as we know it would cease to exist.

The power to tell the Great Story is the power to control the Great Past, and this is really the power that controls how the world is constructed. All the National Parks are necessarily a part of this mythological history, because they represent what is understood to be collective national origin and are infused with what we formally recognize as "significance." From an anthropological standpoint, myth provides the essential pattern for proper human behavior. It tells members of society what is meaningful, even what their own life "means."

The Planning Process

With the relationship of interpretation to ritual and ideology in mind, it seems worthwhile to consider how decisions that affect a formal interpretive program at a National Park are made. The enabling legislation that establishes a National Park, which must be passed by both houses of Congress, contains the rationale for the park's existence. Generally, the legislation is quickly followed by the formulation of a mission statement, which elaborates on the reasons the park was established. It also describes the natural and cultural resources of the park and in general terms presents a plan for their protection. Having laid this groundwork, a more comprehensive planning document is prepared.

Such a comprehensive planning document, a master plan, was prepared for Bent's Old Fort in 1975. It emphasized the fort itself as a kind of museum display, describing the intent to include authentic period furniture in the fort and to reenact events that occurred during its occupation. Interpreters would be dressed and trained to act as key figures in the history of Bent's Old Fort. Interpretive strategy would capitalize upon the most striking, and most controversial, aspect of developing the historic site—the massive physical reconstruction of the fort.

Reconstructions are not often done by the National Park Service because they are only infrequently in conformance with National Park Service policy regarding the management of cultural resources. Exceptions are rare and, inevitably, precipitate a storm of controversy. Opposing positions are argued within the Park Service itself, and an antireconstruction coalition is almost always victorious. A reconstruction usually involves, and more frequently implies, a degree of speculation that the National Park Service finds unacceptable. The visitor to a National Park, so the line of reasoning goes, should be able to depend upon the fact the

materials they are seeing represent what was actually present at the time being portrayed.

Every effort is made to preserve the original materials, the historic fabric, of the site, for two reasons. First of all, historic fabric is preserved so that the visitor can feel secure that what he or she is seeing is authentic. Each incidence where this policy is not followed erodes the trust the public has learned to feel for the National Park Service and the integrity of its historic sites. The second reason has to do with the preservation mandate of the National Park Service. The original material—the bricks and mortar of a historic structure or the soil matrix of a subterranean archaeological site—comprises a kind of library for future researchers. We cannot foresee the nature of analytical techniques that will be devised in the future. For example, who would have guessed before C-14 analysis how important a fragment of charcoal, wood, or other organic material in association with a cultural feature could be in determining its precise age? Recent advances in DNA research have led to the analytical capability to identify the species of animals killed or butchered with prehistoric stone tools used thousands of years ago from microscopic traces of blood remaining on these tools.

For these reasons, the relatively nonintrusive and reversible treatments of restoration or stabilization are preferred at historic, or prehistoric, sites. These involve the preservation of historic fabric, using present-day materials and technologies very minimally to achieve this result. This, however, does not produce a completely "authentic" presentation. While we may present what fails within the scope of a historic restoration project with a minimum of speculation, other, misleading, factors are inevitably present in this restored scene. First of all, we have no control over what has transpired just outside the boundaries of restoration projects. The restored 1790S building may be located next to an 1840s home and on a modern paved street. The net effect is something quite different than what would have been presented in the late eighteenth century. In addition, while we can control what goes into a restoration project, we always leave many aspects of the true historic scene out. About some we have no knowledge. About others we may know something, but not enough to justify their inclusion in the scene at the risk of misrepresentation. Finally, the original scene itself was constantly changing. It was dynamic, whereas the restoration must pretend that it did not change. Aspects of the landscape were ephemeral: a garden here one year and not the next, a fence constructed and then allowed to deteriorate, plumbing and electricity installed, a porch added or removed, and so on. A certain point in time must

be selected to represent the entire history of the site, an action that excludes representations of the site as it appeared at other times.

At Bent's Old Fort, the year selected for representation was 1846, the high-water mark of the Bent & St. Vrain Company and the year the fort was used as the staging point for the Mexican War. The selection of this representative point was done after a careful analysis of the site's purpose, which is of course related to the Great Past. The rationale for the selection of 1846 as the interpretive year is presented in the comprehensive management document, which for Bent's Old Fort was the master plan.

Thus, such decisions form the basic structure of interpretation. They determine what is included and excluded from the historic scene, even nonverbally. The nonverbal scene not only is in many ways the most persuasive form of presentation, it is also the most ideological because it conveys what is assumed, normal, or natural—so obvious as to not be worthy of discussion. Only by further, verbal interpretation and critical discussion can such assumptions be made visible, and the restoration transformed into information as opposed to something like propaganda.

This is not to say that a great deal of critical discussion does not go on behind the scenes, and some may involve the public. In 1991, the decision was made to rework the comprehensive management plan for Bent's Old Fort. A new, general plan is produced every ten years or so for each National Park, in recognition of the fact that the social and environmental context in which each park operates changes. Full-scale comprehensive management plans are known as general management plans (GMPs). They require at least two years to produce, in large part because coordination of input to the plans from various National Park Service offices and from the public is time consuming.

The first step in the preparation of a GMP is the formulation of a document called a Task Directive, which presents the problems and issues inherent in the management of the park area and the form in which these will be addressed in the GMP. In effect, this is a contract for services between the staff of the park for which the GMP is being prepared and those most actively involved in its preparation. These people are generally from the appropriate regional office and the central planning and design office for the National Park Service, the Denver Service Center.

A team captain is appointed who is then responsible for the preparation of the task directive and the production of the products laid out there. (The team captain for the Bent's Old Fort GMP was Cathy Sacco; she is bright, energetic, and articulate, as people chosen for these lead positions tend to be.) The team captain is responsible for explaining the purpose

and, as it takes form, the content of the document to the myriad of offices, "publics," and individuals who will become involved in the preparation of the GMP, and in making sure that their involvement is fairly represented there. Individuals are assigned to the planning team from the various offices that will be involved with the formulation of the GMP; again, these are usually the Denver Service Center, the regional office, and the park. This task directive may go through several drafts. There must eventually be a consensus on the acceptability, of the plan by the superintendent of the park, the regional director, the manager of one of the geographically based teams (eastern, central, and western) of the Denver Service Center, the Washington Office, and the manager of the Harpers Ferry Center (the office that has responsibility for producing interpretive materials—films, brochures, posters, and so forth—for all the National Parks).

Once agreement has been reached on this basic document, public input is sought. This input has, at times, resulted in the reformulation of the task directive and necessitated reagreement about the altered document by all involved offices. The team captain and planning team endeavor to notify the public of the impending planning effort in a variety of ways. Besides placing notices in newspapers and at the park, an attempt is made to identify as many as possible of the "publics" who might have an interest in the future of the park. These groups are varied and surprisingly numerous for every park. They generally include Native American groups; naturalist organizations like the Audubon Society; groups interested in the history of the park, such as the Civil War Roundtable or Fur Trade reenactors; those with recreational interests such as organizations of hikers, bicyclists, cross-country skiers, motor-cyclists, fishermen, boaters, and snow-mobilers; groups with special needs such as the blind, deaf, or paraplegic; and organizations who want special access to the park for ceremonies or demonstrations. This latter public has included not only the obvious Native American groups that have traditionally attached sacred significance to landforms in National Parks, but also New Age organizations who request access to mountain peaks, and, recently, a neo-Nazi organization that has claimed Zion National Park as their homeland. All of these groups will bring to the park their own version of history.

Brochures based upon the issues and problems identified in the task directive are sent to the various publics. Input is solicited in writing and, almost always, at public meetings where issues and problems in addition to those identified in the brochure are raised by the publics and recorded,

as are any comments. This record of the meeting and a reformulated list of problems and issues is made available to all the publics soon after the meeting, along with a request for further input. Several meetings are sometimes held.

The planning team then compiles a number of alternative means by which the issues, problems, and comments so far received might be addressed. This list is reviewed by the concerned offices and frequently the publics. Often another public meeting is held at this point, and input on the alternatives is requested. Following this, the planning team selects a preferred alternative and makes it known, along with a rationale, to the concerned offices, and sometimes again to the publics. All concerned National Park Service offices must agree on the selected alternative. Vociferous objection to the alternative on the part of any public can prompt a reformulation of alternatives or a refinement of the preferred alternative.

Once National Park Service offices have agreed upon an alternative, an environmental impact statement (EIS) is written by the planning team, a document that addresses all of the foreseeable impacts of the alternative's implementation. Such impacts might be on the biological, cultural, or social environment. The EIS is then disseminated to the public for review. Frequently, there follow several cycles of comments, revisions, more comments, and more revisions until the alternative is satisfactory to all concerned and the selected alternative is transformed into a GMP.

Based upon this document, an interpretive plan and then a statement for interpretation are formulated. Each of these goes into progressively greater detail about how the interpretive program at the park will be operated. Nonetheless, the essential aspects of the interpretive program—themes and approaches—are laid out in the GMP.

Bent's Old Fort is located (as are many national parks) in a relatively remote and unpopulated area. The park has many strong supporters who desire to be involved in the planning there, even though they live at some distance from the park itself. The Santa Fe Trail Association membership, for example, tends to reside in areas all along the length of the trail, from Independence to Santa Fe. In part because of this reason, public meetings were not held. Nonetheless, a good deal of input was obtained from interested parties. Over 1,000 brochures describing the draft GMP were sent out, and almost two hundred attached questionnaires were returned.

Not surprisingly, the GMP for Bent's Old Fort emphasized the fort's association with the Santa Fe Trail. The plan also highlighted its role in the "opening of the West" and its impact on the indigenous populations of the area, particularly the Hispanic and Native American groups there.

Local Input to Interpretation

The interpretive plan is prepared by either the park or regional staff, or sometimes jointly by members of the staffs of these two offices. The statement for interpretation is usually prepared by the park. A statement for interpretation has been redone several times at Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site by the park staff over the past eighteen years, reflecting some of the social issues that have become more prominent in that time. (This was done even in the absence of such changes in the master plan.) Many of the park staff are drawn from the local community, providing for additional consideration of local interests and concerns in the interpretive planning process. Also reflected in the interpretive program at the park is the increasing emphasis over the past fifteen years within the National Park Service in recruiting employees from ethnically diverse backgrounds. A greater visibility of the historic role of the Mexican population at the fort is probably due in no small way to the placing of a Hispanic female in the key position of chief of interpretation and resource management at the park. While no Native Americans are on the park staff, at least one of the interpretive staff has very close ties with the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, and this is also reflected in the current interpretive approach.

There is every evidence that park staff from all levels of the organization are given a voice in the formulation of the interpretive program, including the statement for interpretation. In November 1991, for example, the supervisory park ranger for interpretation and visitor services at Bent's Old Fort, Steve Thede, met with the interpretive staff—this included permanent employees, the seasonal employees who work only in the summer during peak visitation and who are so much of the interpretive effort at any park (these are often school teachers), and volunteers—to come up with a rough draft of the 1992 statement for interpretation for the fort. The meeting took place away from the fort, to emphasize the idea that new approaches would be welcome and that approaches would be worked out collectively. By design, Donald Hill, the superintendent, and Alexandra Aldred, the chief of the division of interpretation and resource management, did not participate. It was thought that their influence might steer the group toward the interpretive programs of the past as opposed to what might be done in the future.

The longest discussion was the first and most basic: what was the purpose of the park? It was important to the group that the essential theme

be "The Opening of the West" as opposed to "Westward Expansion." To Steve Thede's surprise, when he later checked the exact wording of the park's enabling legislation, he discovered that the law had been written using "the Opening of the West," not "Westward Expansion." To the interpreters at the fort, "Westward Expansion" expressed an Anglo-centric point of view: what transpired was an expansion only to the Americans from the East. The idea of the "Opening of the West" was much more palatable. In this light the fort was seen by all cultures involved as an institution that offered new opportunities: for trade and for an enhanced standard of living to the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and other Native American groups; for American manufactured goods on the part of the Mexicans. As for the Americans in the East, Steve related, the Bents and Kit Carson were like astronauts. Highly romanticized versions of their exploits appeared frequently in eastern newspapers in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, and their names were known to the general public there.

The interpretive staff then set about brainstorming how the interpretation would be accomplished. Some of the ideas—like holding horse races on a reconstructed race track—were quickly discarded. Living history figured greatly in the staff's thinking, for two reasons. First, it provided immediacy, which involved the visitor with the larger story of the fort, a point of departure from which what Steve called "take-home messages" could be developed. Also, it encouraged the visitor to adopt a point of view appropriate to the nineteenth century. At that time, for example, getting to the fort was not as simple as driving there in a car. It was a dangerous undertaking that required careful planning and the assistance of experts. The resources of the fort were vitally important in this context. A place to repair a wagon wheel or a station that provided food and fresh water could be crucial to survival.

Each interpreter then set his personal goals, the "take-home messages" he wanted to give to the visitors. Interpreters were also encouraged to be as explicit as possible about how to measure their own success by formulating statements such as, "seventy-five percent of the people I talk to will know the names of at least two Indian tribes who traded here by the time they leave."

Such discussions as this also readied the park staff to provide input to the planning team as it went about drafting the various documents preparatory to the GMP. Some areas of consensus about the GMP began to emerge. One was to move away from the more unstructured forms of reenactment that took place at the fort in the late 1970s, before the interpretive program was as well developed as it later became. At that time,

troops of "mountain men" would arrive at the fort and relive what they considered to be the frontier experience. Sometimes this would include such anachronisms as leather hand-tooled "holsters" for beer cans (the contents of which, one might assume, would assist them in their efforts to replicate primordial chaos). Reenactors now are, in essence, auditioned and trained. They are invited by an event coordinator from the interpretive staff. Invitations are issued after the decision is made that such reenactors are necessary to the story to be conveyed.

The consensus among those involved with the formulation of the GMP was that reenactments should be put into a larger context. To provide that context, the new GMP recommended that a visitor center be built, where the history of the fort could be presented in a more abstract way. Interpreters typically say that this gives the visitor several choices: they can go to the visitor center first and then visit the historic site, now better prepared to understand what they are seeing, or they can visit the site first, draw their own conclusions, and then compare these to the story the visitor center offers. Alternately, they can decide to only visit the site, missing the official story as presented in the visitor center. Park visitor surveys indicate that some people prefer this last alternative. The same surveys also indicate that almost no one visits only the visitor center; they have traveled to the park, after all, for the experience of visiting the site, even if for only minutes. The visitor center, the plan recommended, should be away from the site, as far as possible, although there is a limit to how far people will (or are able to) walk. Administrative functions would be moved to the visitor center, freeing up more of the reconstructed fort for interpretation. All twentieth-century interpretive devices (like the television and VCR, which in 1991 occupied space in the reconstructed fort) would be moved to the visitor center, too, thus removing a rather jarring intrusion to a portrayal of nineteenth-century life.

The Reenactments

Jack Wise is more relaxed on this Independence Day than is the superintendent. Jack is the executive director of the Bent's Old Fort Historical Association, a private group that has been organized to support the park's activities. Though there are many special events today, his role is unchanged. He and his staff run the store. He feels confident that this is the soul of the fort, just as trade was in historic times. Visitors want

to take something back from their visit, almost demand it. A National Park Service study of visitor activity at Grand Canyon done some years ago, now legend in the Park Service, revealed that the average visitor spent about twenty minutes looking at the canyon, the rest of the time looking for or checking into hotels, perusing menus and eating, and buying souvenirs. (Though there are, of course, many who depart drastically from this average.) The National Park Service does not operate for profit and so delegates the provision of such services to concessionaires. Some of the concessions are run by private enterprises; others, like the one at Bent's Old Fort, are operated by nonprofit affiliates of the National Park Service.

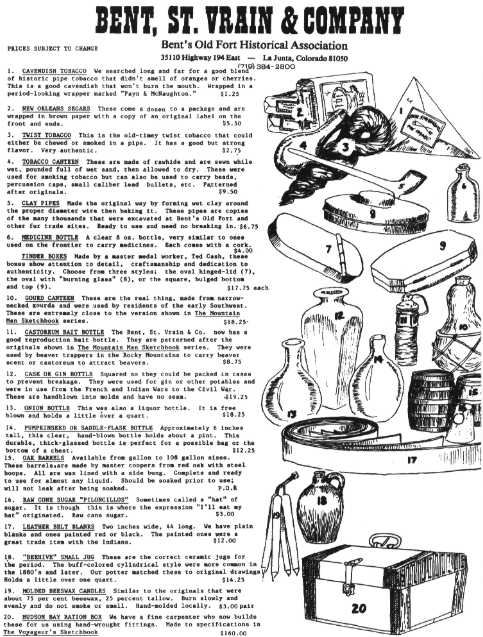

Jack points out that visitors to the fort in historic times came here to do exactly what current-day visitors do, in one respect—to trade for things. And the things he provides are, to the best of his ability, almost exactly like what was purchased here in historic times (fig. 23). No rubber tomahawks here, he declares. The store stocks Hudson's Bay blankets, the real thing, including the white Bent's Fort blanket made especially for Bent & St. Vrain; custom blacksmithed hand tools, hardware, and cooking utensils; hand-made rifles; powder horns, not plastic but real horn, costing from $100 to $115 apiece ("but people buy them, they buy authenticity," says Jack); museum-quality reproductions of redware pottery; black silk scarves ("I pull them out with a flourish and say, 'for you, from the Orient'—they snap them up"); bricks of tea ("the kids can't get over them"). "It's all in the presentation," says Jack. "If you tell them about the item, how it was used and who used it in historic times, they'll buy it. They want to take home a piece of history."

Sales have increased dramatically since Jack took over responsibility for the concession. He attributes the success of the history association's concession to his ability and that of his staff to go into character. It is plain that they are very good. Dressed in period costumes, they seem like professional actors to me. Jack has a thespian's voice; it fills a room easily. He and his association people bring their acting skills to the concession, turning it into a reenactment as surely as is the dragoon camp down by the river.

Still, he is impatient to test the frontiers of reenactment in ways that the National Park Service will not allow. He hands me a flyer for an event he has planned through an organization with which he is affiliated, called Vistas of Time. Each year he has organized a program called "Polk Springs," named for the private ranch where it is held. He tells me that there are haft a million people in the United States who have been involved with reenactments, in one capacity or another, and it is from this

Figure 23.

Page from the 1990 sales catalog published by

Bent's Old Fort Historical Association

group that attenders are drawn. The ad runs, among other places, in magazines for reenactors. It reads, in part:

GREETINGS: THIS IS NOT A REENACTMENT!

We are looking for 100 soldiers right from the Civil War battlefields via the prison pen at Camp Douglas, Illinois, to come West with a galvanized Yankee Infantry Company and soldier in the Indian Wars of 1865 for five full days of very real living history.

This is not a club or regiment being formed with dues and meetings nor are you obligated to anyone in any way. This is strictly an in-depth living history experience where you sign up to soldier in 1865 on the southern plains in Comanche country for five full days. Then you are discharged.

Polk Springs is designed to be a "socio-learning" experience which means you will learn history as it happened and that you may enjoy yourself while learning to live in the past.

On Monday morning, prepare yourself mentally to go into 1865 and not return to the present until the following Friday. Conditions will be identical in every way humanly possible to those of 1865; tough, harsh, and bleak. The experience will wear on you physically and mentally.

Experienced as well as novice reenactors and living historians alike need understand that no one should be offended nor take anything personally. If you are shouted at, threatened or punished for some infraction, it is all in the context of the U.S. Army of 1865, not you as a person today. . . .

There will be no dances, no Sutler's Row, no military balls, no bands or canned music, no referees, no "firing demonstrations," no cars, no interpretive talks, no visitors, no tours, and no cam-corders. There will be virtually no 20th century for five days. This is not a typical event. There will be no reenactments of any battles, no one will "be killed" or "wounded."

HOWEVER, YOU WILL BE FIRING LIVE AMMUNITION!

Discipline by the officers and NCOs will be rigid and tough as it originally was. You will be in the Army for five days and you will be expected to follow orders. You will be in period first person 24 hours a day for five days. There will be no cession of duties at 4:30 PM or any other time to discuss the day's activities, drink cold beer, or listen to Civil War period music on boom boxes. . .. You will not live history as we or any museum or government agency interprets it. You will live history the way it was. We guarantee it.

The almost evangelical fervor with which a past relived without scripts is pursued here reminds me of Mary Douglas's theory that such sentiments are often generated in high-grid, low-group, egocentric societies, the societies of "impersonal rules."[20] Ritual is disdained by those who feel excluded in such societies in favor of direct communication—communication without symbols—with what is sacred and more real, more "authentic." Rhys Isaac noted this also, as discussed in a previous chapter, in

regard to the transformation of Virginia society during the period 1740 to 1790.[21] There was a change in that society from ritual to spontaneity, from hierarchy to egalitarianism, from hospitality to individualism, and from conviviality to privatization. This serves as well as a description of the iconic values of America, values especially related to the American West. Out here on the "frontier" there is disdain for formality, for bureaucracy, for anything, in fact, that limits a person's freedom to do as he or she damn well pleases. Many National Park Service employees who have worked in the "last" American frontier, Alaska, have told me that they were afraid to let people there know that they worked for the federal government. There were stories of nasty, sometimes violent, incidents. Alaskans went north to get away from things like federal governments: governments impose licensing requirements for fishing and hunting, environmental regulations, and restrictions on the use of marijuana.

As I talk to Jack Wise, it occurs to me, not for the first time, that the ethos at work here is very, much like that of the Plains Indian:

The endurance, courage, independence, perseverance, and passionate willfulness in which the vision quest practices the Plains Indian are the same flamboyant virtues by which he attempts to live: while achieving a sense of revelation he stabilizes a sense of direction.[22]

I would venture to say that Geertz has presented here a list of the qualifies that many in America, if not the rest of the modern world, admire most. They are certainly regarded as virtues in the nearby town of La Junta, Colorado, home of the "world-famous" Koshare Indian Dancers (fig. 24). None of the dancers is really Indian. The organization is a Boy Scout Troop. It is much less of an exaggeration to say that the Koshares are world famous. They have danced all over the world and are much in demand wherever the Boy Scouts or similar organizations gather. The Koshares were organized by Buck Burshears, a local man who died several years ago. He was alive when I did my excavations of the Bent's Old Fort trash dumps in 1976, and we had the opportunity to talk several times because he was very interested in what we were finding at the fort. I remember most his conviction that admittance to the Koshares practically ensured a boy's success later in life. Buck could talk at great length about his boys who had become doctors, lawyers, and successful businessmen. In part he attributed these success stories to the discipline it required to be a member of the dancers, but he also felt that the young men were absorbing some of the admirable traits of the Indians: independence, determination, and stoicism.

Figure 24.

Cover of the Koshare Dancers' souvenir publication.

In drawing a distinction here between the National Park Service and non-National Park Service approach to interpretation, I do not mean to say that Park Service personnel are immune to the allure of evangelicalism. Recall that the regional director chose to play the role of the independent, free, and spontaneous trapper instead of the wealthier and more powerful trader. And Don Hill has spent a good deal of time searching through military records for references to his Claremont County, Ohio, ancestors who fought in the Mexican War. He eventually discovered that they had gone through Veracruz, but not Bent's Old Fort. He was disappointed because, as he tells me on Independence Day, he was hoping for the sense of "connection" he understands many of his reenactors to be seeking.

And so while a National Park Service employee such as Alexandra Aldred, Bent's Old Fort's chief of the division of interpretation and resource management, might approach reenactment in a more ordered way than does Jack Wise, it is still with a good deal of passion. Alexandra has worked for the Park Service at Bent's Old Fort since 1968, and a conversation with her soon reveals the qualities—organization, initiative, an innovative approach, and determination—that have moved her from an administrative assistant position (which she held when I was conducting excavations at the trash dumps) to her current job, which is second in authority only to that of the superintendent. In 1976 she was generally known by the Americanized "Alex"; today she gently encourages me to call her Alexandra, pronouncing her name in the Hispanic fashion with softened consonants.

Alexandra shares some statistics with me from the 1991 statement for interpretation. In 1990, visitors were largely families and couples traveling at least overnight and were likely to be relatively well educated and secure financially. A full 65 percent were "through visitors," whereas only 35 percent were "home based" (had departed from and were returning to their homes in the same day). A reported 55 percent of visitors were with family groups, and 17 percent were couples without children. Only 14 percent were local residents (and this counts the busloads of children from local schools), 35 percent were regional residents, 48 percent national residents, and 3 percent international residents. There is a great interest in the site among the German and Japanese visitors, but to get to Bent's Old Fort requires a special effort because it is slightly off direct routes between other major tourist attractions. Only 3 percent of visitors were members of minority groups.

Taking into consideration the composition of her audience, Alexandra is particularly interested in portraying the roles of minority groups in the history of the fort through the interpretive program. She thinks that the living history and reenactment programs convey minority participation in the historic activities at the fort very well. Alexandra explains that the initial interpretive emphasis at the fort on the hunters and trappers, the "mountain men," was a bit misleading since by 1846, the year to which the fort has been reconstructed, these mountain men were no longer frequenting the fort as much. This initial emphasis had been evidence of the powerful link that existed in the thinking of many of the "publics" between the fort and mountain men. There seemed to be some compelling symbolism here. Mountain men—the trappers—perhaps more than any other group held a liminal position between the American and the Native American. Through their intimate association with Native Americans (so we are told by both contemporary and current-day popular accounts), the mountain men acquired some of the Native Americans' most remarkable characteristics: toughness, resourcefulness, disdain for authority, and the ability to survive in the wilderness on their own.

Interpretation is now, however, more carefully based upon research into what transpired here at particular times. This shift in the interpretive focus came as a relief to the park staff, Alexandra tells me. Mountain men reenactments could easily get out of hand. There was a good deal of the drinking and carousing that reenactors associated with the behavior of the mountain men. The reenactors insisted upon the same kind of freedom and absence of societal controls they ascribed to the mountain men.

The Independence Day events—breaking the piñ, firing the cannon, making adobe bricks, cooking food in the plaza, reading the Declaration of Independence, the presence of dragoon and Indian encampments, and so forth—were based upon observations made firsthand by historic visitors to the fort on various Fourths of July. Alexandra discovered all these events in the copies of diaries and notes kept in the fort's library. She worked from the observations of Lieutenant Abert, Susan Magoffin, and Alexander Barclay.

Alexandra is especially pleased because this year, for the first time, a local African-American woman, Phyllis Howard, had agreed to play the fort's famous black cook, Charlotte. Alexandra had tried repeatedly over the years to fill this position by contacting black universities in the South, to no avail.

There have been similar problems in filling the "roles" of Native Amer-

icans and Mexicans for living history and reenactment purposes. Recruiting from the list of potential employees provided by the regional administrative office, the "seasonal register," had not yielded a diverse pool of applicants. Seasonal applicants are allowed to select two parks at which the), would like to work, and those choosing Bent's Old Fort were most likely to be white males. The park has been successful in recruiting for Native Americans on only a few occasions. Each time the recruits were unhappy with being separated from their family groups and went back to the reservations in Oklahoma after a short period. Native Americans at Bent's Old Fort fur trade reenactments are frequently portrayed by Anglos, very talented and dedicated, who bring with them tipis, costumes, cooking equipment, weapons, and other Native American accoutrement they have carefully constructed. Over long reenactment weekends, they will sleep in their tipis down by the river, cooking and living as their careful research indicates that Native Americans did. Meanwhile, real Cheyenne who sometimes come from the Oklahoma reservations to participate in these weekend reenactments usually stay at one of the local motels. Nonetheless, Alexandra never ceases in her attempts to get representatives from appropriate ethnic groups. For the Independence Day observance, she had found a Mexican migrant family from Brownsville, Texas, who were American citizens. Unfortunately, one of the children in the family became ill at the last moment.

Craig Moore, a member of the permanent interpretive staff at the fort, has developed over many years very close ties with the Southern Cheyenne on the Oklahoma reservations. In the spring of 1991, he persuaded the Henry Whiteshield family to come to the fort, where they reenacted the typical manner of ritual exchange in the trade rooms. This proved to be a very moving experience for Craig and many of the interpretive staff, to whom the ritual significance of the reenacted exchange was clear. Henry, gray-haired and distinguished, told me he found it satisfying to be at the fort, and he was gratified at the respect displayed by the visitors who observed the reenacted ceremony.

For the 1992 Independence Day celebration, Craig arranged for the presence of Ann Shadlow and her daughter, Mickey Pratt. Both these women have been very active in the movement to preserve Cheyenne traditions. Ann Shadlow is a storyteller and recipient of the Native American Woman of the Year Award. Her grandmother was Julia Bent, youngest child of William Bent and Owl Woman. Because Julia was present at the Sand Creek Massacre, she, like her brothers Charlie and George, gave up

the white lifestyle that William had tried to encourage them to adopt. Julia married another offspring of an Anglo-Cheyenne union, Edward Guerrier, son of famous mountain man Bill Guerrier. Ann lived with Julia from infancy, and Julia attempted to provide Ann with a traditional upbringing, to the extent of never speaking English or permitting it to be spoken in Ann's presence. She also taught Ann as many as possible of the Cheyenne stories, some of them quite likely thousands of years old. Having told the stories to Cheyenne children virtually all of her life, Ann several years ago responded to what she had by then decided to be the sincere interest on the part of non-Cheyenne and attended the National Folk Life Festival in Washington, D.C. This led to a number of engagements all over the country. At the Independence Day observation, she for the first time told a story in Cheyenne to a white audience.

To Alexandra the fort and grounds are a teaching tool, one that is particularly vital because she has learned that what one experiences is retained much longer and in much greater detail than what one merely hears or sees. Her approach to interpretation was greatly influenced, she says, by a visit to Mount Vernon in the 1950s. She was herded through the home of George Washington in an unpleasant way, and she felt that she had learned nothing. It was as if she were expected to feel privileged to have been permitted to enter such hallowed ground. The opportunity to experience the massiveness of the fort itself is important, she thinks. Alexandra had been at the site for six years prior to reconstruction, looking almost every day at the foundations there. Nonetheless, she was astounded by the scale of the fort as the walls began to rise.