Chapter 7

Circuits of Power

Modern Ends Through Traditional Means

Ritual is the social mechanism that shapes culture and society by producing those preconscious, shared assumptions that are the basis of both. The Western colonial observer sees the role of ritual clearly in what we term "primitive" societies. It is a staple of ethnographies. We proceed from there to assuming that such "nonsense" was left behind by civilized peoples during the Renaissance. This is a symptom of our individualism, what Tocqueville called "the cult of the individual," and is no less a "habit of the heart" than any other mythology.[1]

It is to the realm of affective response that we must look to understand the organizing power of ritual. Society is organized for the most part at this pretheoretical level. What is culture if it is not this? Emotional bonds are focused along the lines legitimated by the operant mythology of a society (in modem societies the "stories" told through novels, television, movies, music, the plastic arts, museums, national parks, historic sites, and so forth—as well as maxims, rumors, history, and various "historical" accounts).

In the nineteenth century, certainly no less than today, the national mythology. centered to a large degree on the notion of the entrepreneur. The entrepreneur had broken with his past, in the way Euro-Americans, who were dominant in the new country., did when they came to the New World. Americans had thrown off the yoke of Old World tradition and had remade themselves. In the nineteenth century., they were still in the process of remaking themselves. As they are now. Like Agonistes, Americans are eternally becoming.

Despite the myth, entrepreneurs had to start from somewhere, like everyone else. And, like everyone else, they were originally defined by the network of social relationships in which they had been embedded by the circumstances of their births. What they became depended upon how this network was extended and transformed, something that could only be done through ritual means. This, of course, is exactly how society operates in primitive cultures as well. In the cultures that we recognize as primitive, social networks are extended through marriage, which establishes new kinship, or exchange, which sets up fictive kinship relations. Both of these extensions of the social network are legitimated through ritual, which acts to sacralize these new relationships by claiming as precedent the behaviors of the gods (or ancestors) who, through that behavior, rescued the world from primordial chaos.

The Bent trading empire was successful, both financially and insofar as its transformative effect on the Southwest, because of these networks. Further, these networks were ultimately linked with a central, panoptic power in the East, one that steered the course of the trading empire to its own ends. The social networks thus became circuits of power. The larger ends of the central authority turned out to be destructive to many of the parties involved in the Bent trading empire—to the Native Americans, certainly, but also to the Bents themselves.

Extending Kinship

David Dary, in a concise and admirable volume titled Entrepreneurs of the Old West, made the statement, in a section about the forming of the Bent & St. Vrain Company, that "Ceran St. Vrain, born in Missouri, had been a clerk for Bernard Pratte and Company in St. Louis before entering the Santa Fe trade about 1824, a few years before the Bents."[2] This is true and informative; however, to really understand who St. Vrain was, what he became, and how this affected the fortunes of the Bent & St. Vrain Company, one would need to say much more about his position in a network of kinship and extended kinship, and how, eventually, this fit into the circuits of power in the early nineteenth century.

Ceran St. Vrain's family had been influential in many quarters prior to his birth. His grandfather, Pierre Charles de Hault de Lassus de Luziere, had held a high position in the government of Louis XVI and was forced

to leave France during the Revolution, in 1790. His two sons figured importantly in the interests of both France and Spain in the New World. Both of these sons had not accompanied their father directly to the United States but had gone to Spain for four years, where they had "gained prominent places in the armed forces of that country."[3] While his sons were in Spain, Pierre had made contact with his boyhood friend in the New World, the Baron de Carondelet, now governor of Louisiana. Through the governor, he obtained positions for his sons, who then joined him. One of these sons, Charles Auguste, became governor of Upper Louisiana Territory and actually officiated at the transfer of that territory twice: once when it was transferred from Spain to France, and again when it was transferred from France to the United States. His brother, Jacques Marcellin Ceran de Hault de Lassus de St. Vrain, was Ceran St. Vrain's father and, for a time, was in command of the Spanish naval vessels on the Mississippi River.

The family's fortunes declined after the United States gained title to the Louisiana Territory. Although Charles Auguste had officiated at the transfer of the territory, he was now without a job. Pierre lost the land he had been granted by the Baron de Carondelet, and Jacques (Ceran's father) became the sole support of the family, through a brewery he had opened.[4] Nine years later, in 1813, the brewery burned down. Neither Jacques's widow nor his brother had the resources to care for the ten children in the family, and so some were offered for adoption. Ceran was the second oldest child, and at eighteen went to live in St. Louis with General Bernard Pratte, a friend of the family.

Ceran until this point in time had been sustained by a network of kinship, the importance of which was reflected in lengthy formal names of the French elite, which amounted to a description of lineage. Nonetheless, his background had prepared him for membership in the modern, mercantile and political network rapidly assuming form in the United States. Ceran had gained business experience working in his father's brewery, which had supported the family when links to the Old World power structure had been severed. Now, he had been accepted into the family of a key Personage in that new system. Bernard Pratte was owner of Bernard Pratte and Company, which was the western agent for the American Fur Company, the largest fur trading company in the United States. Ceran rapidly developed competence in the new system. Assisting him in this was that the new system operated by means of personal relationships only slightly less than did the old. Because of this, much of Ceran's early

socialization would hold him in good stead. He was familiar with not just the languages but also the customs of several cultures. Many who dealt with him commented throughout his life on his gentility and helpfulness. He formed many friendships and maintained these relationships for long periods of time. Living with the Pratte family, he developed two associations that, in particular, would have a great influence on his life. One was with Bernard Pratte Jr., the son of the company's owner; the other was with Charles Bent, son of the influential Judge Silas Bent. These friendships continued even as Bernard Jr. and Charles were sent off for more complete schooling than Ceran was able to obtain. Ceran couldn't afford such schooling. This resulted in a deficiency in his education that was evident in his letters, years later.

Ceran worked for Pratte and Company first as a clerk. He then managed fur shipments, and then became involved in the fur trade at the company's posts on the Missouri River. In 1824, Ceran obtained a supply of goods intended for the New Mexico and Indian trade. Trading and trapping opportunities had just opened there with Mexican Independence in 1821. There were several areas of evident business potential. Streams there were still relatively untrapped for beaver, the New Mexicans were anxious for industrial goods from the United States, and there were furs to be obtained from the Native Americans, particularly at the centuries-old pueblo trading centers such as Taos and Pecos. It made good business sense for Pratte and Company to look in that direction for additional profits. Ceran had proven himself competent. With his background he was a logical choice to be sent to the Southwest. He probably had some knowledge of Spanish, and certainly he was familiar with the customs of the Spanish elite. Ceran may have realized that the newly opened region would offer more room for advancement to a newcomer in the trading business than did the much more established Missouri trade.

The Southwest became of enough interest to Pratte Sr. that he sent another of his sons, Sylvestre, to the Taos area to lead beaver trapping expeditions in 1827. On the second of these, with Ceran as his clerk, Sylvestre was bitten by a rabid dog and died painfully of hydrophobia.[5]

Ceran's efforts to assist and comfort the dying Sylvestre impressed the group of trappers on the expedition. When word of this reached Pratte Sr., it could only have strengthened the ties between Ceran and the Pratte family.

In 1832, Ceran became a Mexican citizen by means of a law that permitted foreign traders to do so as long as they lived in New Mexico, were

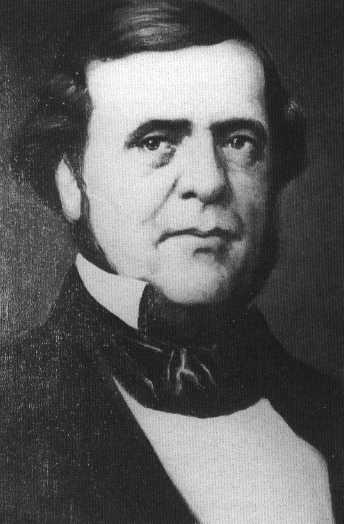

Figure 19.

Portrait of Ceran St. Vrain. (Courtesy Colorado

Historical Society, Denver.)

employed and of good character, and agreed to be baptized in a Catholic church. Thenceforth, there would be no legal ambiguity in regard to Ceran's ability to both trap and trade in New Mexico. Also in that year, Ceran, having already been involved in several partnerships, entered into one with his childhood friend Charles Bent. Both he and Charles were experiencing the same problem, one of timing and capital. Both had goods to sell, but currency was scarce at the time they began their venture and prices were low, pending the return of trappers to Taos. Bent and St. Vrain pooled their resources, with St. Vrain buying out half of Bent's goods, which he stored with his own in a warehouse they had jointly purchased. Ceran, the Mexican citizen, stayed in Taos and awaited the return of the trappers, at which time he sold the goods at a profit. Charles, meanwhile, traveled to St. Louis, where he paid Pratte and Company some, if not all, of the money owed them by St. Vrain and acquired more goods from them. In St. Vrain's flawed writing, he explained to the Pratte Company:

I remit to you by Mr. Charles Bent Six hundred Dollars which you will please place to my credit, I am anxious to now the result of the Bever I Sent last fall, and would be glad you would write me by the first opportunity, and let me now what amount I am owing your hous, if you have not Sold the mules I Sent in last and Mr Bent Should want them doe me the favor to let Mr Bent have them, it is posible that I will be able to Collect, Some of the debts due to the estate of S. S. [Sylvestre] Pratte, as yet I have not collected the first cent. there is no news in this Cuntry, worth your notices more than money is verrey Scrse, goods Sells low and duties verrey hie, but Still prospects are better here than at home.[6]

The letter goes on to reveal that Charles Bent had suggested this arrangement (which became Bent & St. Vrain Company).[7] Note that St. Vrain said that he would attempt to collect the debts due to the estate of Sylvestre Pratte, a kindness no doubt appreciated by the Prattes. There are signs that St. Vrain was becoming well established within the political network, too. In 1834, he was appointed U.S. Consul at Santa Fe. In that same year, John Jacob Astor sold the American Fur Company to Pratte, Chouteau and Company of St. Louis.

Some years later, this close relationship with Pratte would again play a role at a crucial juncture of the Bent & St. Vrain Company. In 1836, Ceran St. Vrain sent R. L. (Uncle Dick) Wootton as head of a trading expedition well north of the established Bent & St. Vrain Company trading boundaries, into Sioux country. In exchange for the ten wagons of trade goods

they had brought north, Wooton brought back robes and furs worth $25,000. This could have set off cut-throat competition of the kind in which the American Fur Company had engaged against the well-capitalized Union Fur Company, and others, in the Missouri River trade. In the end the American Fur Company, with more resources than the others, had always forced the competition out of business. The Bent & St. Vrain Company was already concerned with the ambitious smaller companies attempting to move into the Southwest. Some of these smaller firms, like Sarpy & Fraeb, were tied to the American Fur Company. And Bent & St. Vrain Company had just suffered the expense of buying, from Sarpy & Fraeb, Fort Jackson and all of its merchandise and peltries, because Fort Jackson was located on the northern periphery of the Bent & St. Vrain wading area.[8]

But instead of conflict, the American Fur Company and Bent & St. Vrain Company entered into a noncompetition agreement, as follows: "Bent, St. Vrain & Co. shall not send to the north fork of the Platte, & Sioux Outfit [acting for the American Fur Company] shall not send to the South Fork of the Platte [sic ]."[9] This was done almost casually, by means of a half-page document, with Ceran signing for Bent & St. Vrain.

The agreement, to be sure, was not without benefit to the American Fur Company. Traders seeking to widen their margin of profit by now were attempting to bypass the St. Louis trading houses when purchasing trading goods.[10] Manuel Alvarez, for example, was not only going to New York and Philadelphia, where he could save considerably on the price of wade goods, but was also attempting to make arrangements with houses in London and Paris.[11] Bent & St. Vrain, in comparison, faithfully bought their trade items from the American Fur Company. In May of 1838 alone, for example, the company paid the American Fur Company $I3,257.33 for goods and supplies. In return, it received a virtual monopoly on the Southwest trade and the tacit backing of the most powerful of the fur trading firms. By 1840, the Bent & St. Vrain Company was second only to the American Fur Company in the amount of business transacted.[12]

Ceran's ties to other prominent New Mexican traders and to New Mexicans were solidified through marriage. He was first married to a daughter of Charles Beaubien by Beaubien's marriage to a Mexican woman. Beaubien was active in the New Mexico trade as early as 1830.[13] Later, Ceran married Louisa Branch, daughter of Alexander Branch and his Mexican wife. Alexander Branch was another wealthy trader in New Mexico and, for a time, Ceran's business partner.[14]

Kinship Ties to Native Americans

William Bent's upbringing was one of gentility. His father, Silas Bent, had been born in Massachusetts where, according to family legend, his father, Silas Bent Sr., had participated in the Boston Tea Party. After studying law in Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia), Silas Jr. had received an appointment by Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin as principal deputy surveyor for the newly acquired Louisiana Territory. Moving to St. Louis in 1806, he was appointed justice of the Court of Common Pleas the next year, and later a Supreme Court judge of the Louisiana Territory. Silas Bent was one of the Americans moving into the power vacuum left after members of the French aristocracy, such as Ceran St. Vrain's father and uncle, were removed from positions of authority in the territory. Silas Bent's new importance in the community led to his acceptance by the old guard businessmen, such as Bernard Pratte and Auguste Choutcau—and, eventually, to his son Charles's friendship with Ceran St. Vrain.

William became involved in the fur trade several years after his older brother, Charles, had entered the business. Even before Charles and Ceran St. Vrain formed their partnership in Taos, William had been occupied in building a trading post on the Arkansas. He was doing this in 1828, although whether in that year he was building one of the temporary, stockades, beginning the massive Bent's Fort, or both, is unclear. In any case, by 1832 the newly formed Bent & St. Vrain Company met with its first great success, the caravan to St. Louis with at least $190,000 worth of silver bullion, mules, and furs. While some of this was profit from the Santa Fe trade, a good percentage of this value was in buffalo robes. The caravan had reached St. Louis safely, due in part to Charles Bent's legendary skill at organizing and managing such an effort, but also in part to safe passage given through the land of the Cheyenne.

More than anyone else, it was William Bent who was responsible for the amiable relationship of the firm with the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Photographs of him at the fort show an individual who might be mistaken for a Native American, a determined scowl on a dark complected face with high cheekbones (fig. 20). As the French trappers had found, and as William Bent as a young man in St. Louis had in turn learned from their stories, the maintenance of a successful relationship with the Native Americans involved adopting their customs. Part of this was participation in the calumet ceremony. Bent followed this first, essential act of forging kinship tics with an acknowledgment of the continuing, reciprocal com-

Figure 20.

Photograph of William Bent. (Courtesy Colorado

Historical Society, Denver.)

mitment such a relationship entailed. In fact, William Bent would recognize this throughout his life, acting as an advocate for the Cheyenne and Arapaho until his death.

His allegiance to his new kin was soon tested in several ways. About 1829, a group of Cheyenne came to the trading stockade William Bent had erected. Two of the party stayed on after most had left. A Comanche raiding party appeared on the horizon, and Bent hid the two Cheyenne. The Comanche leader, Bull Hump, saw the tracks of the Cheyenne and demanded to be told where they were. Risking attack by the Comanche, Bent replied that the Cheyenne had left—thereby saving their lives.

Bent was willing to alter his manner of doing business as much as possible to accommodate the traditional behavior of the Cheyenne. This can be seen in his decision to build the large permanent structure that became known as Bent's Old Fort in the general location where the Cheyenne Chief Yellow Hand had indicated the Plains tribes yearly trading rendezvous to have occurred. As mentioned earlier, there is evidence that this general location was also where the Mexicans had been trading with the Cheyenne for furs just a few years before.

Bent was also willing to accept the enemies of the Cheyenne as his own. The incident in 1834 when William Bent joined the Arapaho and Cheyenne in an attack on their bitter enemies, the Shoshoni, illustrates this. The fact that the Shoshoni had been trading with Bent's rival in the fur trade on the Arkansas, John Gantt, and that the attack took place with Gantt looking on and not lending any help, discredited Gantt in the eyes of the Cheyenne and Arapaho.

The most unequivocal evidence of Bent's commitment, from the Cheyenne point of view, would have been his marriage to Owl Woman in 1835 and, when she died many years later, the taking of her sister, Yellow Woman, following Cheyenne tradition. These actions, and the offspring of these unions, transformed fictive kinship relations into actual ones. Other key personnel associated with Bent's Old Fort took Native American wives, also. George Bent, younger brother to William, married a Cheyenne woman named Magpie (although he also seems to have had a Mexican wife). Kit Carson (as a young man) was married to an Arapaho woman who bore him an adored daughter, Adaline.[15] After the Arapaho woman's death, Ceran St. Vrain refused permission for Carson to marry his niece, in part, apparently, because of Carson's half-breed daughter. Carson then married a Mexican woman from a prominent family, who was the sister of Charles Bent's wife.

But it was the continuing ritual exchange with the Cheyenne, repeated

many times over, that may have most affected the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Making it all the more impressive was that it took place at the massive adobe fort, which had the look of a natural feature, rising abruptly from the Plains. The panoptic bastions offered perspective into the Indian camps, as well as into the plaza and the room blocks that surrounded it. The bastions also inspired awe because they were well fortified with a variety of weaponry. The layout of the fort resembled in some ways the medicine lodge or tepee with sacred associations to the Plains Indians, but its axis mundi was the fur press in the middle of the plaza (fig. 17).

If the Cheyenne did not qualify as the company's private army, it was only because the company staff and allied traders and mountain men better qualified for that title. Resistance from the Cheyenne would have undermined the trading operation. With their help, the resistance of other Native American groups was neutralized and their aggression was turned against the Mexicans. It was only with difficulty that William Bent was able to prevent the Cheyenne tribe from traveling to Taos to avenge his

brother Charles's death in 1847.

Secret Societies

Charles Bent, being William Bent's brother, shared a network of kinship with him, which he extended in different directions, although in similar ways. While William saw to the operation of the fort and had as his primary concern relations with the Plains Indians, and while Ceran St. Vrain (although he was a great traveler) attended to the warehouses and stores in Taos and related operations, Charles looked to the east. Initially, this was to the trading houses of St. Louis, but in time his gaze extended to the seat of government in Washington, D.C. As we have seen, by the time of the Mexican War, Charles was in frequent secret contact with military leaders, such as Kearny, and with politicians, including such remarkable characters as Senator Benton and President Polk. It was through these contacts that he was installed as the first American governor of New Mexico.

While Ceran St. Vrain may have had "fictive kinship" ties with the trading houses in the East, it was Charles Bent who suggested how they could be used. After the partnership had been set up, it was Charles who went to St. Louis, taking with him a letter from St. Vrain to his contacts there. Power and politics attracted Charles.

Charles, the first-born of eleven children, was a determined man (fig. 21). Where associates thought Ceran quiet and gracious, they saw Charles as dynamic. A measure of his fierceness can be taken from two of the many letters he wrote to Manuel Alvarez, U.S. Council in Santa Fe. These letters were prepared in February 1841, the first on the nineteenth of that month and the second, although it is undated, probably sometime between the twentieth and the twenty-fifth. In an uncharacteristically sloppy hand, the first of these relates how he had just come from a visit with Juan Vigil, which he made in the company of a Mr. Workman. The visit was to confront Vigil with a copy of certain "false representations" he had made about Bent and Workman to the governor:

I then asked him how he dare make such false representations against us he denied them being false. The word was hardly out of his mouth, when Workman struck him with his whip, after whipping a while with this he droped it and beate him with his fist until I thought he had given him enough whereupon I pulled him off. he run for life. he has been expecting this ever since last evening for he said this morning he had provided himself with a Bowie Knife for any person that dare attack him, and suiting the word to the action drew his knife to exhibit. I supose he forgot his knife in time of neade. . .. I presume you will have a presentation of the whole affair from the other party shortly. . .. I doubt wether you will be able to reade this I am much agitated, and am at this time called to the alcaldis I presume at the instance of Jaun Vigil.[16]

The next letter is much more legibly written and relates how Bent was in fact called before a judge in the presence of Vigil. Vigil, according to Bent, made many threats against both him and the judge: "He particularly threatened to raise his relations and friends if the Justice did not do him Justice, according to his will."[17] Bent was ordered to prison, but he objected that there was no evidence against him except the word of Vigil, who had not actually accused Bent of doing him violence (Workman did the beating, at least in Bent's version of the event). The judge then ordered Bent to Charles Beaubien's house, to be employed in lieu of prison, but Bent again objected on the same grounds. Finally, the judge put Bent under house arrest, in his own home, and collected an undisclosed amount as bail. Bent was still aggrieved at the incident but was obviously much calmer than he had been when writing the first letter. He was waiting for the governor's decision, the judge being about to present the case to him, and he hoped for a favorable one:

I think the Governor is not a man entirely destitute of honorable feelings he well knows there are cases that the satisfaction the law gives, amounts to noth-

Figure 21.

Portrait of Charles Bent. (Courtesy Colorado

Historical Society., Denver.)

ing. I had rather have the satisfaction of whiping a man that has wronged me than to have him punished ten times by the law, the law to me for a personal offence is no satisfaction whatever, but cowards and women must take this satisfaction. I could possibly have had Vigil araned for trial for slander but what satisfaction would this have been to me to have him fined, and moreover I think he has nothing to pay a fine with, he is a vagabond that lives by fletching his neighbor.[18]

This was still the age of the duel, and Bent was a man of his times. Bent, who became governor of New Mexico six years after this incident, had run afoul of New Mexican law before. One of these occasions was associated with the 1837 insurrection against an unfortunate named Albino Perez, a governor who had been sent to New Mexico by Santa Anna, the president of Mexico. To put down the rebellion (instigated in part by Manuel Armijo, who had been governor in the 1820s and was miffed at recently being removed as customs collector), Perez obtained supplies from American merchants in Santa Fe with promissory notes. The supplies were not enough, and Perez's force was defeated. Perez himself was beheaded. Armijo saw in this the opportunity to regain power, and he forced American merchants to supply his troops. So supplied, Armijo defeated the rebel force and was proclaimed both governor of the province and commander in chief of the army (the position he held at the time of the Mexican War). Since Bent had supplied two factions in this conflict, he was imprisoned in Taos. Ceran St. Vrain led a rescue party to Taos from Bent's Old Fort but was met on the way by Charles, who had gained his release by bribery and by threatening to have his men burn down the town.

A slightly different presentation of these events appeared in The Builder,

a magazine of the Masons, in an article in the December 1923 issue tifled "Governor Bent, Masonic Martyr of New Mexico." The article was written by a Taos lawyer and Mason, F. T. Cheetham, who had earlier done an article for another local Masonic publication called "Kit Carson—Mason of the Frontier." In truth, it appears that Charles Bent and Kit Carson, along with Ceran St. Vrain and William Bent, as well as the ill-fated Albino Perez and Santa Anna himself, were all Masons. (The same issue of The Builder points out that twenty-three signers of the Declaration of Independence were Masons, as were eighteen Presidents of the United States—not to mention Benjamin Franklin.) According to Cheetham's article, Bent was imprisoned because he was mistaken for a member of Perez's Masonic order, the "Yorkinos," from south of the border.[19] Perez had instituted progressive reform measures in New Mexico, on the orders of Santa Anna,

said Cheetham. One was a decree providing for public schooling and the institution of a direct tax to pay for it. That there is some validity to Cheetham's thesis is supported by David Lavender's research, which confirmed that the idea of the direct tax was likely the major inflammatory issue behind the rebellion.[20]

As may be seen in this particular incident, in the nineteenth century fraternal organizations such as the Masons provided a means by which an increasingly fragmented society could organize itself around values and beliefs that held a high emotional content. The author of Secret Ritual and Manhood in Victorian America , Mark C. Carnes, theorized that this was a reaction against the feminization of religion in Victorian America.[21] But Masonry had been in existence before Victorian times, as had the Odd Fellows. The spate of fraternal organizations that seemed to copy Masonry, and which went on to become so popular in the Victorian age, also arose before this time. Many were formed between 1840 and 1870. They shared the qualities of being ecumenical, in that they usually favored no specific religion, and secular, because many, like the Masons, steadfastly promoted the separation of church and state.

There are some obvious exceptions here, if organizations like the Mormons and the Knights of Pythias are accepted as fraternal orders. But Mormonism and the Knights of Pythias as well as some of the organizations with a more obvious political or special interest agenda that arose later in the nineteenth century—the United Mechanics, the Know-Nothings, the Knights of the Golden Circle, the Grand Army of the Republic, the Ku Klux Klan—capitalized upon the obvious enthusiasm for ritual displayed by members of the older fraternal organizations like the Masons and the Odd Fellows.

This should not obscure the fact that members of the earlier organizations rallied around what they saw, at least, as the implementation of Renaissance ideals. Such ideals held that the application of rationality to the problems of society would result in a better world. Thus, these organizations were opposed to "archaic" and "corrupt" systems, like those their members saw in New Mexico. The overthrow of the old order there by the more enlightened Americans was a matter of principle. Cheetham quoted an observer in New Mexico some years after the Mexican War:

The annexation of New Mexico to the United States brought it under their Catholic ecclesiastical authorities, and they knew well what to expect from any bishop who might come from us. . .. A bishop was sent from the United States. There was a general suspension, unfrocking, dismay and howling among those

Mexican priests (and it would have been difficult to find exceptions), who "kept cocks and fit 'em, had cards and played 'em, indulged in housekeepers of an uncannoncal age, and more nieces than the law allowed."[22]

These hypocrisies had been enough to stir righteous indignation among the Masons in the Southwest—especially Charles Bent and Ceran St. Vrain. They found the church, and especially the infamous Padre Martinez (who all in the Bent & St. Vrain Company later blamed for Charles's death), opposing them and their influence at every turn.

But if the goals of the Masons and other fraternal organizations embraced the application of reason, then why advance such goals with a mechanism so irrational as ritual? Throughout the United States in the nineteenth century, middle-class men, often the leaders of their communities, expended a great deal of time and money on obsessive participation in what seem sophomoric rituals.

It was Carnes's thesis that although there were evident advantages to the creation of a bond with what amounted to the most influential group of individuals in many towns, it was the ritual activity itself that was the great attraction in secret societies. He noted that rituals were typically so elaborate that they left little time for anything but participating in or witnessing them. Contrary to popular belief, secret society meetings, especially during the later nineteenth century, were not given over to drinking and socializing. Carnes thought that, for nineteenth-century males, "in some sense the present had proven barren, devoid of emotional and intellectual sustenance."[23] By looking to a mythological past, fraught with symbolism, men could reclaim meaning for their lives. Even their participation in modernity was transformed into a kind of calling. Opposition from organized religious groups, notably the Catholics, was stimulated when it became known that the Masons and similar organizations taught that redemption depended upon the exercise of the human capacity for reason.[24] Middle-class experience could resonate meaningfully with reference to the mythology provided by the secret societies:

An arch in a railway station might bring to mind the temple of Soloman, an onerous business contract might gain meaning as a form of Babylonian captivity, and a business reverse could be seen as the "rough and rugged road" on the return to Jerusalem.[25]

So must a Cheyenne forced to a life of agriculture have seen the humpbacked shape of bison in every clump of sod turned over by his plow. Ironically, the "free" and egalitarian life of the Indian was held up as a

kind of paradisiacal model by some of the secret societies: "The Improved Order of Red Men . . . advised initiates to emulate the children of the forest, who held all wealth and property in common." In commenting upon this subversion of capitalism, Carnes cited Victor Turner's idea that some such rituals are an essential part of the "dialectal process" of society. Certain rituals are permitted that are in "opposition to existing hierarchies and rules." These may eventually bring about change.[26]

John Brewer offered a more functionalist explanation for the origin of Masonic and other secret societies in eighteenth-century England. In that society, the "patrician" class held such sway in the early 1700s that "the middling sort," as Brewer puts it, were driven to pool their resources.[27] The dearth of capital produced a situation in which indebtedness posed a constant threat to any merchant. Merchants, most succinctly, had a cash flow problem. Their clientele consisted of members of the upper class who were habitually late in the payment of their bills. This was considered a prerogative of the class; in time, it was a mark of the class. Unfortunately, the merchant's creditors had to be more concerned with punctuality. Debtor's prison was a constant threat. This was especially so as economic cycles seemed to occur in an absolutely unpredictable manner, at the mercy of fad and panic. Clubs were formed as mutual aid societies: to lend financial assistance or social pressure if loans were called, to provide support for widows and orphans, and so on. Brewer noted Dr. Johnson's comment that almost every Englishman belonged to a society, lodge, fraternity or club.

But the stated nature and organization of these clubs as reported by Brewer raises less functional considerations. Some of these clubs were organized along lines of the interests of the members. Brewer mentions "spending clubs" and "drinking clubs." As he put it, "Every taste was catered for: societies were established for literati, the ugly, gamblers, politicians, homosexuals, rakes, singers, art collectors, and boating enthusiasts."[28] Like the Civil War reenactors, Corvette Clubs, and birding societies of today, this segmentation was really the expression of a desire for intimacy and support. Often clubs stressed reciprocal obligations among members who "transcended traditional social, economic, and religious boundaries." Masonic and pseudomasonic societies as well as these interest-based clubs "boasted of the way in which they united Anglicans and dissenters, men from different trades, merchants and gentlemen, whigs and tories, in common association, promoting unanimity and harmony where only conflict had previously existed."[29]

All these clubs provided protection against the "arbitrary nature of misfortune."[30] This strikes me as nothing other than Eliade's "terror of his-

tory," the capricious events of the temporal world that can rob a life of meaning, or end it. The traditional response to this is to build a bulwark of ritualistically contrived meaning against the threat of chaos. Interpersonal relationships are configured or reconfigured in time of crisis with reference to and along the lines of eternal archetypes, which are themselves reflections of neotenic fantasies of enduring unity. This occurred no less among the "solid burghers and respectable tradesmen who made up the bulk of masonic membership." Thereafter:

Masons would rally round a brother whose creditors threatened to foreclose on him. The knowledge that substantial friends, as well as kith and kin, would stand by a tradesman increased his creditworthiness and the confidence that both he himself and others had in his business.[31]

This is an apt description of the sorts of relationships Charles Bent developed over the course of his life. These relationships were an integral part of the success of Bent's Old Fort. What Brewer described as occurring in eighteenth-century England transpired in the nineteenth-century United States and, by the second quarter of the nineteenth century, in the Southwest. As we have seen, the Masonic network by then reached all the way to the president of Mexico.

Brewer made a great point throughout his article of the tension between the aristocracy and the "middling sort" in England and saw the establishment of clubs and secret societies as a strategic move on the part of the middle class in the conflict between these groups. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it was a social development that held certain economic advantages for many individuals and groups in the middle class. A problem with using the word "strategic" (as I have myself used it upon occasion) is that it calls forth the image of a general on a battlefield with immediate power to deploy his troops and weapons. That was not the case here, and what the word might inaccurately imply is that the Masons constituted a monolithic organization that had as its end the surreptitious control of nations, in the manner of an eighteenth-century "Tri-Lateral Commission." Another drawback to couching the events in question in such terms is that they might obscure that "strategic" moves, with the rationality that the word implies, were implemented by traditional concerns, and were driven by them as well.

If one proceeds from what I consider to be the phenomenological premise that the first item on the human agenda is to make sense of the world, whether the humans in question are in traditional or modern societies, then what stands out in sharp relief is that individuals from all

classes were scrambling in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to establish new identities. Class lines, particularly in the United States, were not impermeable. Members of the "patrician" class were throwing their lot in with middle-class entrepreneurs; entrepreneurs were seeking upper-class partners for the associated prestige and as well as the access such new partners would have to politically and economically influential people and institutions.

Bent & St. Vrain Company provides an obvious example. Among the attractions held by St. Vrain in the Bents' perspective were in all probability his connections with Prattes and others and his genteel manner, which was conducive to further such connections. St. Vrain, for his part, must have seen the advantages of tying his fortunes to the Bents, with their business and legal acumen, as well as their drive, innovation, and ability to understand and communicate with a variety of people—the qualities of the entrepreneur. Yes, there was financial and social maneuvering here, but this maneuvering was not on the part of nor for the interests of "class." As important, there is no reason to think that the financial benefits were the only, or even the most important, motivation for participation in clubs or secret societies in either eighteenth-century England or nineteenth-century America. Participation might better be thought of as more generally aimed at the establishment of an identity in a society where amassing wealth was important to such ends. The final goal was not wealth, but what the wealth was imagined to represent.

This brings us to the second question posed some paragraphs above. Why advance "rational" goals—the modernizing goals of the Enlightenment, if you will, or the goal of rationalizing the credit structure, if you are functionally minded—with a mechanism so "irrational" as ritual? The answer is that nothing else would do. Social movements require that values be internalized, and there is really no other way to generate "sentiment" and impart values than through ritual. It is also important that however "rational" the goals might have been, the motivation to achieve goals is not rational—it is emotional. Among humans, emotions are invariably tied up with making sense of the world and one's place in it.

The rituals practiced by these organizations were, as previously discussed, initiation rituals. Mircea Eliade identified three basic sorts of these, at least in "primitive" societies: rites marking the transition from childhood or adolescence to adulthood, rites for entering a secret society, and rites of initiation into a mystical vocation.[32] The second of these is the one that arises in the most recognizable form in modern society.

Secret societies are historically recorded everywhere. Most often these

are men's societies, Männerbunde. Eliade acknowledged the theory that has gained wide acceptance among scholars of religion, that masculine secret societies are a reaction to matriarchy. Their object according to this theory is to frighten women and shake off female dominance. But Eliade noted that we do not see this occurring everywhere in reaction to matriarchy, and he pointed out that men's secret societies share many similarities with the initiation ceremonies associated with puberty. Eliade thought that such secret societies might arise, more generally, when notions of masculinity (or femininity, too, for there are Weiberbunde ) need to be reen-forced, as a result of cultural change:

It is for this reason that initiation into the secret societies so closely resembles the rites of initiation at puberty; we find here the same ordeals, the same symbols of death and resurrection, the same revelation of a traditional and secret doctrine—and we meet with these because the initiation-scenario constitutes the condition sine qua non of the sacred. A difference in degree has, however, been observed: In the Männerbunde, secrecy plays a greater part than it does in tribal initiations.[33]

The description of such rituals fits exactly those of the nineteenth-century fraternal organizations. Eliade went on to speak of reasons why secrecy is more important in Männerbunde than in puberty rituals. Primary among them is the factor of social change. He pointed out that these secret societies never arise where indigenous peoples have retained, unchanged, their ancestral traditions. But frequently,

the world changes, even for primitive peoples, and certain ancestral traditions are in danger of decay. To prevent their deterioration, the teachings are transmitted more and more under the veil of secrecy. This is the well-known phenomena of the "occultation" of a doctrine when the society which has preserved it is in the course of a radical transformation. The same thing came to pass in Europe, after urban societies had been Christianized; the pre-Christian religious traditions were conserved, camouflaged or superficially Christianized, in the countryside; but above all they were hidden in closed circles of sorcerers.[34]

Christianity, as Clifford Geertz and others have noted, became a "world religion," along with Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam, because its theology could accommodate any number of smaller, regional, and more parochial religions. It used the instrument of rationality to form this durable theology, which was in this way more ecumenical than the religious systems of thought that had gone before. Secularization, after the Renaissance, demanded even more "ecumenical" belief systems, ones

more properly in the realm of philosophy, but operationalized as ideology. The search was on for evidence of "natural law," which did not depend upon supernatural explanations for natural phenomena. In many ways, this was the central intellectual story of the nineteenth century, as evidenced, for example, by the zeal with which the concept of evolution was embraced by many upper- and middle-class individuals during that period. Secularization was essential in the rapidly emerging modern world of the nineteenth century, especially for the middle class. Ways had to be found to accommodate this secularization, but also to assuage the growing sense of anomie that such rapid social change often produces. Accommodations took a somewhat bizarre form, for they depended upon a mechanism—ritual—that seemed to violate some of the basic tenets of the new ideology, of objectivity and rationality. The tensions engendered by these contradictions were such that the ideal of secularization and rationality had to be all the more enthusiastically, and publicly, embraced.

There was obvious anxiety among middle- and upper-class American men in the nineteenth century concerning their proper identity in the rapidly changing society. This is evidenced in any number of ways, including the strict codes of honor and the many duels in many regions of the country; we see these at work in Charles Bent's letters about his fight with Juan Vigil. It had to do with the general breakdown of traditional social structures and value and belief systems. While not as acute as that transpiring among Native American groups, or among the populace of New Mexico, the American populace was undergoing the same sorts of stresses. These were all the more severe in the Southwestern frontier. Conditions were extremely uncertain there; danger to life was a real factor in the equations of everyday experience. There was no family structure of the sort in which most of these middle-class individuals had grown up. The danger and hardship of the frontier rendered it an unfit environment for Anglo women, to this way of thinking. It was anything but a "normal" environment for the Easterners.

With the displaced American males, as with the Plains Indians, there

was really nothing left with which to make up a life other than trade and warfare, and the panoptic culture of modernism and the fictive kinship system of the secret societies easily accommodated these interests. They were, in fact, a perfect match. The panoptic system provided the means by which the new order could be implemented; the "kinship" systems provided a way of reinforcing both that system and the values and beliefs that made the implementation seem important. In this sense, panopticism was the how , the secret societies the why.

The combination proved very. powerful; it set in place the "circuits of power" that implemented the agenda of the central authority in the East. As Foucault could have predicted, the state eventually took over the panoptic mechanism. In England and France, what had been in the hands of private religious groups or charitable organizations soon was taken over by the state, once panopticism was established, producing a single authority responsible for all social order. Foucault provided a quote from an enthusiastic Parisian official: "All the radiations of force and information that spread from the circumference culminate in the magistrate general. . .. It is he who operates all the wheels that together produce order and harmony. The effects of his organization cannot be better compared than to the movement of the celestial bodies."[35]

Here is evidence of the sacralization of panoptic power, a sacralization just as evident in the rituals of the middle-class, male secret societies of the nineteenth century. Such power becomes sacred, or "natural" in terms of modern ideology, when it claims as its referent the endlessly recurring cycles of nature and the mysteries that were known to the ancestors. But now in the celestial archetype is seen the grids of logic; the "clockwork universe" becomes the "music of the spheres." This grid was imposed on the land-scape as the panoptic power, facilitated by ritual means, became firmly entrenched. Along with trails came telegraph lines, railroads, fences, settled lines of private property, and political boundaries. All of this tended, too, from the tangible to the more abstract. Trails and railroads gave way to political boundaries, which today yield to lines of communication and authority accessible to only those who have been grounded in their peculiar workings. The land, again, assumes fewer obvious points of reference.

Such logical grids have as an aspect of their control the power to locate and to settle. Foucault put it this way: "One of the primary objects of discipline is to fix; it is an anti-nomadic technique."[36] Among the first casualties of the new order were the nomads: the Plains Indians, the free-ranging trappers, and the traders with their caravans.