Chapter 6

Bent's Old Fort as the New World

Ideology and the Establishment of Political Hegemony

The Mexican War to the south of New Mexico dragged on for two years. Deep in Mexico, American forces were met with strong resistance. In Mexico City, teenaged cadets from El Castillo battled the invaders, becoming martyrs. Today, school-aged children are told about El Niños Heroicas and how one cadet, rather than surrender, wrapped himself in the Mexican flag and hurled himself from the battlements. Almost 14,000 of 104,000 American troops died in the Mexican War (most from disease), producing a death rate higher than any other war in American history.[1]

The opposition to the American presence below New Mexico makes the war as it occurred in that northernmost province of Mexico quite remarkable. The contrast between the conflict in the two areas is stark. In New Mexico, the war was brief and largely bloodless. Resistance on the part of a very few was more than balanced by support of the change in government expressed by many. For the most part, the populace was quiescent.

The war in New Mexico had been won before General Kearny's Army of the West crossed the Arkansas River in 1846, won by the troubled alliance of Americans and Native Americans and those American traders who had infiltrated deeply into New Mexico and had altered its ideological, social, economic and political infrastructures. Ceran St. Vrain had become a Mexican citizen in 1831 and was an influential businessman in

that country even as he worked actively to acquire New Mexico for the United States. The lieutenant governor of New Mexico in 1846 was Juan Bautista Vigil, once a tariff collector whom American traders would sometimes employ to assist in the timely movement of their goods in and out of New Mexico. He lost his job as tariff collector for using his position to help settle a private debt, but he subsequently held various public offices.

The same Juan Bautista Vigil "welcomed the conquerors with an impassioned speech" as General Kearny led the American troops into Santa Fe. Kearny then made a speech of his own, in which he proclaimed that the religious practices of New Mexico would not be disturbed, that his army would pay for anything they took from the populace ("not a pepper, nor an onion will be taken by my troops without pay"), that the army would thenceforth protect them from the Apache, the Navajo, and other predatory tribes, and that their allegiance to Mexico and the Governor of New Mexico, Manuel Armijo, was absolved.

Armijo had fled.[2] A few years earlier, Armijo had made land grants to several American traders who had then become citizens of Mexico, including Charles Beaubien and Ceran St. Vrain. Later, Beaubien and St. Vrain donated parts of their very large grants to the American citizen Charles Bent—and to Armijo, the governor who had provided them with the land in the first place.[3]

Governor Armijo was also General Armijo. Although he had maintained dictatorial control of his people, such control was not enough to stem the cultural sea-change instigated by the trade with the Americans. By the eve of the invasion, Armijo could see that events had moved beyond his control. It is generally believed that both he and his second-in-command, Colonel Diego Archuleta, were bribed in some way by the Americans just prior to the invasion to insure that no resistance would be offered.[4] Howard R. Lamar offered a recap of the evidence for this in his introduction to a reprinting of Susan Shelby Magoffin's diary, Down the Santa Fe Trail and Into New Mexico. Susan Magoffin, the teenaged bride of Samuel Magoffin, a wealthy trader, documented her experiences as she traveled west with her new husband on a trading expedition that took place just before and during the Mexican War.[5]

Samuel's brother James had preceded him into the New Mexico trade and was at the heart of the political intrigues that formed one of several subtexts to the Mexican War. James Magoffin had been summoned to Washington in 1845 by Senator Thomas Hart Benton, the man who engineered so much of America's policy of Manifest Destiny. Benton in-

troduced James Magoffin to President James Polk. Polk was enough impressed with him at this and a second meeting that he instructed Secretary of War William L. Marcy to direct General Kearny to send James Magoffin to Santa Fe ahead of his troops. Magoffin's instructions were to strike a bargain with the authorities in Santa Fe for a bloodless takeover of New Mexico.

James Magoffin raced back to Missouri, then down the Santa Fe Trail in a buckboard in order to catch General Kearny's army and his brother's trading caravan. The trading venture would be the "cover" for his presence in Santa Fe. He caught up with both at Bent's Old Fort. General Kearny and James Magoffin consulted there, almost assuredly in the dining room with William and Charles Bent, then Kearny sent twelve men under a flag of truce with Magoffin to Santa Fe.

In Santa Fe, James Magoffin met clandestinely with Governor General Armijo and Colonel Archuleta. Archuleta was to prove the more difficult of the two Mexican military leaders in the negotiations. Armijo and Magoffin were not strangers. Magoffin had married a high-born New Mexican woman and was Armijo's "cousin by marriage." Whether money was given to Armijo as a part of the agreement reached is unclear—but certainly Armijo's dealings with the Americans had resulted in personal financial gains for him in the past. Almost surely Magoffin persuaded him that the American takeover was inevitable and thus any armed resistance would be futile. Colonel Archuleta may have been inclined to fight anyway, being a proud man, but it seems that he was swayed by the argument that the American occupation of eastern New Mexico would clear the way for Archuleta to seize the western half of New Mexico, across the Rio Grande. In the end, Armijo fled with the regular soldiers while Archuleta disbanded the New Mexican volunteers. No military resistance was offered to General Kearny's Army of the West.

By 1846, the Indians had become allies (or were, at least, pacified), and, with Kearny's victory in Santa Fe, the United States had gained a firm hold in the Southwest. This was accomplished through ideological means, all of them dependent upon ritual, and Bent's Old Fort had provided a "ritual ground" for the propagation of this ideology, one that resonated with the archetype for all such "monumental" constructions. The structure and grounds of the fort conveyed the form of the new world order. Items traded there facilitated a ritual that altered traditional beliefs. Perhaps, surprisingly, the survival of traditional means for group solidarity among the Anglo elite helped them in their efforts to mount a cohesive and successful campaign of domination in the region.

Nonspoken Definitions and Redefinitions of the World

Modem culture is one of capitalism and individualism. Through capitalism and individualism the world is interpreted and placed in rational categories, quantified, and controlled. The ideological basis of modern culture was and is propagated not only through philosophies, theologies, manifestos, and statements that purport to embody this ideology and therefore to make it available for discussion and criticism, but also by, and perhaps most effectively by, material manifestations of that ideology. Bear in mind that ideology determines what is assumed, what is taken to be the normal or natural conditions of society and the "world." These are not infrequently imaginary conditions that have been institutionalized and reified. As a part of this process, they have been embodied by the material world, where, for the most part, they are unavailable for criticism. They appear to be grounded in nature, in the material, assumed, and natural world around us; that is, they are unavailable for criticism and discussion unless one can interpret material culture by linking it to the mythology to which it refers.

Only in a special and general sense, which I will describe here, does material culture communicate as does language, despite the fact that both are symbolic and can thereby constitute new meanings. Language is a particular case within the general realm of human communication (see the discussion below of Gidden's structuration ). It is the most explicit means of communication available to us. In the modem world, which depends upon explicit communication to function efficiently, we have fallen into the habit of thinking of it as the only means of communication. This is not so. Non-explicit, nonverbal communication, in fact, is often more effective for many human purposes. Even with language, metaphor, compared to explicit description, is usually the more effective means of provoking emotional response, sustaining interest in the audience, and motivating this audience to action.[6] It is probably this that Nietzsche had in mind when he said, "Above all I would be master of the metaphor." Provocative ambiguity—between the conditions of this world and the "real" and enduring (mythological) one—is an essential part of ritual. It is achieved through symbol, setting, and linguistic metaphor that refer to primordial creation.

Ian Hodder, to cite one observer, presented a number of differences between how meaning is attached to language as compared to material

culture in "Post-Modernism, Post-Structuralism, and Post-Processual Archaeology." He notes that material culture is less logical and more immediate than language, is often nondiscursive (which, of course, depends upon the way in which discourse is defined, as Foucault might point out) and subconscious, and often seems ambiguous. Perhaps Hodder's most important observation is that while speech and writing are linear—the reader knows where to begin and how to follow the symbols logically—material culture is not.[7] To me this suggests that meaning does not inhere in material culture by means of an internal system of symbolic logic (since formal logic is associated with material culture only tangentially), but that its meaning is assigned through social use. This is a major difference. Since it is not possible to identify any formal, logical system of meanings in material culture (in contrast to language), I suspect that meaning can be assigned to material culture only through a social mechanism that provokes an affective response. Such mechanisms are properly termed ritualistic. Ritual reenacts the primordial relationships, the relationships that produced order—produced the world—from chaos. As we have seen, there is good reason to believe that neoteny in humans explains much of the importance attached by humans to these primordial relationships. The protracted human childhood, which provides learning opportunities well into and, in fact, throughout adulthood and the associated lengthy dependency of the child, render such primal relations psychologically paramount. The mythology and rituals of a culture are a collective reworking of these relationships in symbolic form. Thus, all material culture derives its meaning by reference to social relationships—and these relationships are sanctified or legitimated through ritualistic means.

Material culture, like language (and ritual), both embodies and creates meaning. Anthony Giddens (although inclined toward neither a post-modern nor a phenomenological viewpoint) developed a theory, of structuration that covers all forms of symbolic action, including language and nonverbal communication like material culture. In this, he posited a "practical consciousness" that intervenes between the unconscious and conscious, between our more basic neurological activities and our thoughts themselves.[8] This practical consciousness is the arena for the innumerable rules, strategies, and tactics that one must use to understand symbolic expressions or to convey meaning symbolically. An attempt to bring these conventions to full consciousness would preoccupy one to the extent that efforts made to understand or convey meaning would be rendered futile. Knowledge of the rules of linguistic grammar and syntax provide an example. We do not usually decide carefully at a certain point in a conver-

sation that a complete sentence with noun, verb, and direct object would be appropriate and then go about constructing such a sentence with careful attention to the rules of grammar. Rules of grammar are held, at best, semiconsciously, but one "knows," nonetheless, not only what sounds "right," but how to organize sounds in a way that will be understood. Thus, structure is employed by practical consciousness to convey meaning. Depending upon the conversation, this process may be employed to restructure meaning (if for example a new word or language is being learned, or at a different level if a particularly cogent point is made). The process of structuration applies equally to all forms of communication including material culture; language is not privileged here.

Consider a well-known instance of communication via material culture provided by Rhys Isaac in The Transformation of Virginia. Between 1740 and 1790, noted Isaac, the "open" floor plan of the typical Virginia house became "closed." Entry, into a house at the beginning of this period was usually into a communal hall, a living space into which the visitor stepped immediately. By the end of this period, the hall had been transformed into a much smaller room. This was not a living area, but really a liminal area designed to provide a buffer zone between the "public" world exterior to the house and the "private" realm of the house's inhabitants.[9]

This transitional chamber both reflected the emerging cultural sensibilities in regard to individualism and privacy and acted to institutionalize them. Such sensibilities thereby became a part of the environment. Isaac tied this new architectural style to a variety of cultural changes that he documented to have occurred at about the same time, including changes from a ritualistic to evangelistic form of religion and the move from a plantation to an entrepreneurial economy. He did not identify a mechanism by which the cultural change he had documented found expression in architecture (or, elsewhere, in the landscape). I suggest that the operant mechanism is one of ritual—fugitive ritual to be sure, but ritual nonetheless, in that the architecture expressed the new ideal ("real") order. The order was propagated by the emotional response it evoked in all who were exposed to it. That affective response was undoubtedly complex and, in the end, may have provoked unintended consequences. As a tactic for bolstering the status of the inhabitants of the house, for example, it may not have been fully successful. Nonetheless, the architecture of the house almost surely assuaged the anxieties of those who lived there in just the way ritual would, by demonstrating to the inhabitants, if no one else, their proper place in the world. Others outside the developing mercantile "grid" may have felt excluded.

Nonetheless, the architecture conveyed to everyone something about the ideology to which it referred, despite differences in reaction to that message. One could replace the word "ideology" in the last sentence with "mythology," if thinking about it that way makes it clearer. What is most interesting about the architecture and landscape of Bent's Old Fort is that it expressed a new world order in a way not only satisfying to its builders, but extraordinarily convincing to so many others.

Panopticism

Michel Foucault has termed the culture of modernity, capitalism, and individualism the culture of discipline. He compares this to a more simple form of culture which operated by means of "spectacle," that is, a certain kind of ritual and the internalization of shared values and beliefs characteristic of ritual.[10] This culture of shared values and beliefs is one that operates according to Durkheim's mechanical solidarity. Every person in such a culture is so alike that society can go on operating in essentially the same manner despite the loss of one or even a group of these individuals. In a modern organic society, an industrial one in which there must exist a multiplicity of specialized activities, all of which must be coordinated in order for society to operate effectively, a much greater degree of individual difference must grow up. Socialization becomes problematic since each person must now be individuated or differentiated in order to be successfully socialized. This is all accomplished in a more idiosyncratic context, one in which each individual's particular environment for socialization, especially his or her primary caregivers, can exert the deciding factor on socialization.

"Mistakes" occur. Individuals—imbeciles, criminals, invalids, and so on—are incompletely or perhaps incorrectly socialized. These mistakes exert a destabilizing influence on the intricate balance of the modern society, and some means must be devised to deal with them. Initially, these means were crude, extremely physical, and each in their own way spectacular, designed to attract attention by means of their extreme nature. For criminals they included the extraordinary forms of punishment Foucault described in careful detail: torture, drawing and quartering, and so on. But larger, increasingly diverse, specialized, and more individualized populations could not depend upon spectacle for a number of reasons. Spectacles could not be devised that were accessible to all individuals and

segments of large populations simultaneously; further, differentiation of individuals and population segments (especially classes) was conducive to the emergence of a more modem society, while the relatively unreflective sentiment elicited by spectacle was not. In time, means more suited for the control of an increasingly diverse, specialized, and individualized Population were devised. These were forms of surveillance.

The embodiment of this form of control, with all of its implications, is found in Jeremy Bentham's architectural innovation, the panopticon .[11] The panopticon was a machine for the amplification of Power, so said Foucault. It was, as such, a way to propagate the modern ideology, for panopticism was also "the abstract formula for a very real technology, that of individuals."[12] In other words, panopticism produced individuals, as defined by the ideology of individualism, through the sanctification of personal discipline.

The symbolic import of the panopticon and its effect upon society requires some discussion to make clear. I think that the ritual value of the panopticon is overlooked by Foucault or, at least, underplayed as he constructed his argument by contrasting this new form of control with the "traditional" forms of "spectacle" and internalized values. It is as if the only sort of ritual were "spectacle." In fact, Foucault is describing another form of ritual, one which operates through the mechanism of the panoptic tower.

Individualism is more than a "technology," it is a belief and value system. It is the aspect of ritual that gives individualism—and capitalism and modernity—the moral force that it has. People subscribe to these ideas not only to avoid negative consequences: They embrace them as concepts that give structure and meaning to their lives. Here religion and ideology are clearly fused, as those concepts have in fact (as Weber pointed out long ago) been incorporated into Protestant belief. Quentin Skinner has pointed out that terms like frugality were coined as Protestantism took hold. Other words like discerning and penetrating were for the first time used in a metaphorical sense to describe talents. Before the rise of Protestantism, to call someone ambitious or shrewd was to express disapproval; as individualism grew apace, these became admirable traits. Prior to the cultural transformation, to say that someone acted obsequiously would be to express approval of that person's behavior; afterward, the same term would be unflattering.[13]

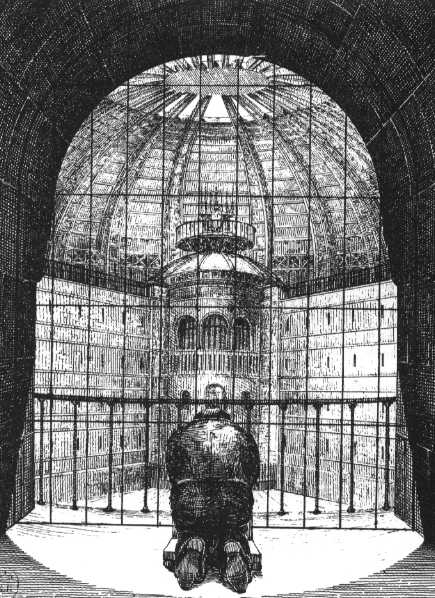

Bentham's architectural invention was a tower surrounded by an annular building (fig. 16). Each room in the ring of rooms extends the width of the building and has windows facing the courtyard and the exterior;

Figure 16.

An example of panoptic architecture, circa 1840. (From N. Harou-Romain,

"Plan for a Penitentiary"; reported in Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish:

The Birth of the Prison [New York: Vintage, 1979], 172.)

exterior windows provide illumination, to put the person in each room "on stage." The tower windows open to the inner side of the ring, and a supervisor standing in the tower can observe activity in all of the rooms. It appears the opposite of a dungeon: light where the dungeon is dark, open where the dungeon is closed, and accessible to observation where the dungeon obscures. But here, "visibility is a trap."[14]

Surveillance can be constant—or not. Those within the cells never know when they are being observed. Observation might be for only a few hours, even minutes, during one day, but the observed have no way of knowing when those hours or minutes might be. They cannot see into the tower, and this is an important point. They must assume constant supervision. Eventually, they must take this task of supervision on themselves. The observer occupies outposts in their minds, so to speak.

The panopticon becomes a machine for surveillance, but one more insidious and far reaching than might first be apparent. Observation, for example, can be delegated to associates, friends, even servants or employees. The person in final charge of the establishment needs only to resume his observation post to see whether the person to whom he has delegated this task has accomplished it correctly. He can tell in a glance if the machine is running smoothly or if the changes he ordered are being implemented according to plan. More important, the panoptic tower is available to inspectors from a central authority. As Foucault stated, "An inspector arriving unexpectedly at the center of the Panopticon will be able to judge at a glance, without anything being concealed from him, how the entire establishment is functioning."[15]

Thus the director of the establishment is himself under surveillance, by the very means that he employs for his observation. Everyone falls under the panoptic gaze. It is this extension of order and the accomplishment of plan that is the final goal of the panopticon. The panopticon was first utilized in situations of deviance and marginality, that is, at hospitals or prisons, where it was especially important to society that the behavior or condition of deviates, who threatened the fine balance of an industrial society, be altered. So the panopticon becomes also an outpost for the scientific method in society—for social engineering, among other things. Treatments in hospitals can be applied to individuals and the results monitored, statistics generated. The routines of prisoners can be altered. The authority. can direct more or less reading or medication, a greater or lesser time in solitary confinement, and so forth.

And here we can see something that Foucault did not emphasize: The

nature of the reinforcement as well as the intent of the treatment applied by the observer can be positive as well as negative. The picture painted by Foucault was one resembling Orwell's 1984—Big Brother is always watching and waiting to punish. In modern popular mythology, the watcher is as likely to be a kind of Santa Claus, who "sees you when you're sleeping," and knows when you are awake, bad, or good. Even more to the point is the Biblical depiction of an omniscient God who "knows when each sparrow falls."

Big Brother, Santa Claus, God—real power, the cultural kind, always comes not from contemporary constructs, but from those of the past. Foucault was really talking about the development of something like the superego, the name modern society has attached to that portion of the human "mind" that embodies social beliefs and values and is associated by virtue of human neoteny with parental authority. These beliefs and values are in this way secularized, partitioned off in the society as they are believed to exist in a separate "place" in the "mind." As the architecture and philosophy of the panoptic tower spread—as panopticism, as Foucault called it, spread, God became the anonymous observer at the workplace or the university, where modern man must go both in order to survive physically and in order to establish a social identity. Identity can now be bestowed by only this faceless watcher, which many would identify in the twentieth century as the spirit of "Taylorism."[16]

In a manner of speaking, the whole of society becomes a workplace, the work of which is, to quote from Bentham's preface to his Panopticon, to accomplish these goals: "Morals reformed—health preserved—industry invigorated—instruction diffused—public burthenss lightened [sic ]."[17] It is important to see here both that panopticism is linked to the implementation of Renaissance ideals and that this implementation comes about, at base, through ritualistic surveillance that refers ultimately to a ubiquitous aspect of even personalized mythology, the neotenic belief in the legitimacy of parental authority.

Bent's Old Fort was just this kind of device. First, it was a device for surveillance. Surveillance began with the observation and control of the population inside the fort—traders, bourgeois (factors), clerks, trappers, hunters, craftsmen, workmen, herders, laborers, workmen's assistants, and, occasionally, Cheyenne and Arapaho—and the Native Americans outside the fort; but it did not end there. As time went on, the fort was more and more frequently visited by important representatives of the central authority in the East. These were military personnel and traders with political ties, in particular. Visitors could see at a glance that the Bent & St.

Vrain Company had the situation under control. This impression was only enhanced because the observations available at the fort were not limited to those directly made from the bastions there. They included those gathered by the company's representatives on the south side of the Arkansas. These representatives, with the support of the company, had infiltrated the society, economy, and govemment to the south. To do so they utilized ties forged by trade and marriage—ritual ties.

The fort was a device to advance the agenda of the Renaissance: the culture of modernity, capitalism, and individualism. The principals of the Bent & St. Vrain Company were firm believers in the benefits of rational order to society and the primacy of the entrepreneurial individual in this new scheme. All were members of the Masons, an organization that celebrated these values and strove to inculcate them into society at large. Panopticism provided the design for the circuit of power needed to implement the new order, while ritual and ritualism brought the connections in this circuit into being.

The fort did not conform exactly to Bentham's description of the panopticon; however, there were special conditions at the site of its construction, and the differences from Bentham's basic design were adaptations to these conditions. The central tower was replaced by two towers, the bastions at the northeast and southwest comers of the fort. Supplementing these towers were walkways along the top of the first story, of rooms, and the windows facing the central plaza on the second story, rooms inhabited by the upper echelon of the fort. The towers at the opposite junctures of the exterior walls were necessary because surveillance was needed outside of the fort as well as inside (see figs. 8 and 10). The fort occupied alien territory and was subject to attack by Native American groups as well as by Mexicans (particularly since Mexico was located just across the river). Native American groups commonly camped just outside the walls of the fort. Usually these were the Cheyenne and Arapaho, who were only allowed inside the fort’s walls at certain times during daylight hours, and then only in certain interior areas such as the trade and council rooms. The presence of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, well armed and equipped by the Bents, was usually enough to discourage visitors from other tribes, except during parlays and negotiations. But skirmishes were not uncommon in the vicinity of the fort. In the late 1830s, as a part of a campaign to eliminate the fort, the Comanche stole all of the horses grazing outside of the fort and killed the man guarding them. In 1841, Robert Bent, a young brother of William and Charles, was killed by Comanche on his way to the fort.

Discipline at the fort was strict, and those who broke the rules were whipped. Banishment from the fort was the most severe punishment and could have fatal consequences in the harsh environment outside of the fort's walls. This discipline supported a strict class system. From highest to lowest, some of the occupational groups within this class system were: the owners of the fort, William and Charles Bent and Ceran St. Vrain; their relatives and distinguished visitors from the East; the bourgeois (the factor); traders; clerks; trappers; hunters; craftsmen; workmen; herders; laborers; workmen's assistants (the last four of these groups were often Mexican); the Cheyenne; and other Native Americans. In all cases, entrepreneurs—independent traders and trappers, for example, who were "free agents"—were accorded higher prestige than were hired traders, trappers, hunters, and guides. A case in point was that Kit Carson, who was originally hired as a hunter and a guide and had worked for the Bents since childhood, was considered socially inferior even after he had achieved wide fame. Ceran St. Vrain would not allow Carson to marry his niece, Felicite St. Vrain.[18]

One measure of the disparity between classes can be seen in the yearly salaries drawn by personnel at the fort. The owners, of course, were not salaried but shared in the immense profits of the fort. By 1846, Bent's Old Fort was the largest of all fur trading posts, except for the outpost owned by the American Fur Company, Fort Union, far to the north on the Yellowstone River. Even in 1832, the Bent caravan from Santa Fe headed east with $190,000 to $200,000 worth of furs, bullion, and other valuables. The fort bourgeois was paid from $2,000 to $4,000 each year, and compensation declined from this high point according to an individual's position on the fort's occupational ladder. Experienced clerks and traders who had mastered Native American languages earned $800 to $1,000 each year. Less experienced interpreters received $500 each year for this service (although they often were paid for other duties in addition to interpreting); an inexperienced clerk might sign on to gain experience for $500 over three years of "apprenticeship," besides which he would receive a suit of fine broadcloth. Hunters were paid $400 each year, but also realized profit from the hides and horns of the animals they killed (which could be an appreciable amount, considering that the fort demanded an average of 1,000 pounds of meat every day).

All of these occupations belonged, at least marginally, to what might be regarded as the "entrepreneurial class." Not only did they provide compensation at a substantially greater rate than did positions of lesser prestige, but the degree of compensation depended upon the measure of

"competence and luck" each could demonstrate. As Mary Douglas has argued, competence and luck are the personal attributes most valued and most essential to success in a high-grid, low-group, ego-centered society of the type linked to modern capitalism.[19] Nonentrepreneurial positions carried with them not only much less prestige but also much less pay: craftsmen and workmen might receive $250 a year, a workman's assistant never more than $120 annually, and a laborer or herder about $100.[20] Native Americans, of course, operated in the murky twilight of their traditional society from the point of view of the capitalists at the fort. While trade was of vital concern to them, and profit of increasing interest (the better to amass wealth), trade was always seen by them as ritual exchange or barter, and wealth was not measured in currency, but in horses or, later, buffalo hides and women. Even as late as 1865, when a Cheyenne raid on Julesburg, Colorado, claimed the strongbox with the Fort Rankin payroll, the "green paper" inside was "gleefully chopped up" and scattered to the winds.[21]

The movement of each class was restricted to certain areas within the fort and the immediate landscape of the fort. The Bent and St. Vrain Company controlled access to points of surveillance at the fort: the bastions, in particular, from which activities both inside and outside of the fort could be surveyed, and also the room just above the zaguan, the watchtower, which afforded a perspective both inside and outside of the fort. That these locations connoted power is evidenced by symbolic material associated with them. On the northeast bastion was a small brass cannon. This was of limited tactical value in an actual fight but was fired at ceremonial times, such as the Fourth of July, and at the approach of large contingents of Native Americans or visitors from the East. Flying from the watchtower atop the zaguan was a very large American flag. The placement of this flag held an important symbolic power. The zaguan, after all, was one of the locations in the landscape of the fort most fraught with meaning. It was the most liminal of places, where the transition was made from outside to inside, from the "chaos" always associated with the "wilderness" or the land of the "other," to the creation of the new order. The flag proclaimed this new order to be American. Here we can see, again, the ritual underpinnings of the new culture of panopticism and rational control. It was a ritual woven into the tapestry of everyday life at the fort.

The Company, usually in the person of William Bent, also dictated who occupied the second story of rooms. As an anonymous employee of the fort reported, the "private rooms for gentlemen" were "perched on the very top."[22] This reflected the elite classes' concerns with privacy , the

privacy of the individual, as well as their desire to be in a position from which surveillance could be made (of course, these rooms might also have been quieter and cleaner).

As documented by archaeological research, as well as some contemporary accounts, permanent fort staff like blacksmiths, carpenters, wheelwrights, gunsmiths, cooks, tailors, and, at times, a barber were assigned work and sleeping rooms on the ground floor, as were the lower status Mexican workmen, who slept many to a single room. The trade rooms were also here, accessible for brief periods to newly arrived trappers, mountain men, and Native Americans who were under surveillance constantly while at the fort. Freighters and other transients might be allowed to stay inside the fort's walls but were not assigned rooms. They camped and cooked in the plaza, eating and sleeping just as they did while on the trail.

More elite staff and visitors were quartered in the upper tier of apartments. The bourgeois during the 1840 remodeling of the fort (a time during which Bent & St. Vrain Company was preparing to expand its trading empire and its influence) was Alexander Barclay, who eventually built Barclay's Fort at Moro, New Mexico. Barclay was an Englishman, born to genteel poverty because of an improvident father. According to Janet LeCompte, he was "determined to be independent, to make his fortune, to become a man of property and to live like one—the theme ran through all his letters and impelled all his actions."[23] Another who participated in the remodeling of the fort was Lancaster Lupton, who first visited the fort as a young lieutenant with the First Dragoons under Colonel Henry Lodge in 1835. He later built Fort Lupton on the South Platte River in Colorado. In this we see some of the capacity of the panopticon to multiply and extend the culture of modernity, as was mentioned by Foucault. We recognize this as well in the tenure at the fort and later exploits of "frontiersmen" and "mountain men," the shock troops of this culture, and many of these individuals became iconic figures, contributing images to a mythology for the new culture.

What may not be recognized by many today is that these frontiersmen became symbols of the progress of modernity in their own time. In his memoirs, Kit Carson recorded a strange incident in his attempted rescue of a Mrs. White, who had been kidnapped by the Jicarilla Apache. After some hesitation on the part of the officer commanding the rescue party, the fleeing Jicarilla shot Mrs. White with an arrow through her heart. When Carson found her body, it was still "perfectly warm." Carson was stricken with regret, even more so when:

In camp was found a book, the first of the kind I had ever seen, in which I was made a great hero, slaying Indians by the hundred, and I have often thought that as Mrs. White would read the same, and knowing that I lived near, she would pray for my appearance and that she would be saved.[24]

And so, as Foucault also observed, panopticism worked and multiplied itself in two directions: Those who dwelled under the panoptic gaze were disciplined and moved on to discipline others. These were entrepreneurs like Alexander Barclay, Lancaster Lupton, and others, as well as the frontiersmen who acted as the infantry of this invading cultural force. But those who controlled the panoptic "tower" were exposed to the observation of "inspectors," representatives of the central authority who scrutinized the panoptic establishment for conformity with the ideals of the elite culture. In addition to military officers, influential entrepreneurs, bureaucrats, and political emissaries, some who came to survey the fort were writers who cast the events that they observed there into a form compatible with reigning cultural values. These writers included Matthew Field, Frederick A. Wislizenus, Marcus Whitman, Lewis Garrard, Francis Parkman, Thomas J. Farnham, William Boggs, Albert G. Boone, Susan Magoffin, and Lieutenant Abert, who drew as well as wrote what he observed.

Prevalent Eastern attitudes were echoed by these authors, but we can also recognize in their works many approaches to the historic West popular today—ones that they helped to establish more firmly, and to pass on. Lewis Garrard, whose observations were first published in 1850 as Wah-to-yah and the Taos Trail, was a young man of means who ventured west to bolster a frail constitution. The West offered a healthy environment and adventure. Garrard was a tourist. Francis Parkman recorded his observations with scientific precision. He was a historian, and his 1849 The Oregon Trail is today held in high regard. Other specialists within the emerging modernity, were well represented among this group. Matthew Field, of course, was a journalist who would find fame especially during the Civil War. He boiled down experience to essential images, the sound-bites of an earlier age. It was he who coined the term "castle on the Plains" for the fort, one widely quoted and used thereafter.[25] Wislizenus was a naturalist; Marcus Whitman, a missionary; George E Ruxton, an author.

Susan Magoffin, the young bride of Samuel Magoffin, regarded what no white woman had previously seen with the surprise and a certain disdain appropriate to "a wandering princess," as she referred to herself in her diary. Documentary evidence indicates that she, like many of the other

authors, stayed in the upper rooms (although Garrard and some others probably did not). Even though confined to bed in this room because of a miscarriage suffered at the fort (due, one must suspect, to the physical exertion and discomfort she experienced on the Santa Fe Trail), Magoffin remained aware of many of the activities in the fort, to the point of observing, "I hear the cackling of chickens at such a rate sometimes I shall not be surprised to hear of a cock-pit."[26] She was concerned about the gambling at the fort, just as she was about certain habits of the Mexican women: combing their hair in public, showing bare arms and ankles, smoking, dressing their hair with grease. She found it "repulsive to see the children running about perfectly naked."[27] Nonetheless, she recorded this all carefully. Although her diary was probably intended only for her family, Lamar noted that she modeled it after Josiah Gregg's earlier Commerce of the Prairies .[28] This very act of careful observation and recording identified her as a member of that class which has as its duty to "observe performances . . . map attitudes, to assess characters, to draw up rigorous classifications."[29] This is the culture of discipline, the panoptic culture.

All of this is of no small import as a means by which the outmoded culture is criticized and conditions "improved." The incessant collective gambling at the fort, for example, was a survival from an older world, that of rank as opposed to class. Gambling in a modern society does not disappear—it is, rather, enshrined as an egalitarian means of upward mobility, one that depends upon the "luck" that those without access to class-based "competence" must rely upon in order to establish a social identity.[30] But this sort of gambling must be an individual effort, one man against all others, against the "fate" that is the metaphorical expression of the social forces that hold an individual's identity in place (or in check, depending upon how one looks at it). This is the gambling of the poker game or the lottery—winner-take-all. Gambling at the fort, the sort that Mrs. Magoffin could not help but notice (with what seems to me to be a jaundiced eye), even while her life was in danger, was the collective kind, group against group, the gambling of cock fighting and horse racing. Mrs. Magoffin registered no disapproval at the billiard room on the second story, only surprise that such a remote outpost of civilization could claim one.[31] Billiards, after all, was a gentleman's game, one that matched the individual's personal competence against all others. But cock fighting and horse racing were passé and now associated with the lower classes. In the eighteenth century they were the passions of tobacco planters, the "old" elite in the East, but had since fallen out of favor as a new way of life emerged, that of middle-class mercantile capitalism. Rhys Isaac noted this in The Transformation of Virginia:

Intensely shared interests of this kind, cutting across but not leveling social distinctions, serve to transmit images of what life is really about. The gentry, having the means and assurance to patronize sport and to be seen playing grandly for the highest stakes, were well placed to ensure that their superior social status was confirmed among the many who took part in these exciting activities. In a community where many of the participants could identify each other as personalities or as members of known families—and thus were bound to observe the proper formalities of deference and condescension—the congested intimacy of collective engagement only served to confirm social ranking. In this respect the operations of a face-to-face, rank-structured society, differ radically from those of an impersonal "class" society, where such mingling is distasteful partly because it does introduce confusions of relationship.[32]

The appropriate class separation was affected by the segregation of the elite at the fort to the second floor of rooms. Mrs. Magoffin was attended by a physician, Dr. Edward L. Hempstead, who apparently occupied the room next to hers. Dr. Hempstead was more than the fort's physician, he was also the chief clerk there. In an age of less advanced differentiation, of less specialization, this made perfect sense; both occupations were pre occupied by the modern obsession with counting, analyzing, and logically arriving at cures for the conditions that were seen as deviations from the socially defined states of physical and fiscal "soundness." Hempstead was a nephew of Manuel Lisa by marriage and a member of a prominent St. Louis family. Not far away on the second floor was, for a time, a schoolteacher, another harbinger of discipline and the improvement of the "self." The schoolteacher, George Simpson, is known to have habitually dressed in a frock coat and silk hat some years later in the nearby town of Trinidad, Colorado, lest there be any mistaking his social identity.[33]

The same sort of segregation was seen in the eating arrangements, a facet of life at the fort remarked upon by many observers (who usually regarded it as another sign of civilization) and one that is striking today in the National Park Service interpretive program at the fort. The owners (William Bent and whoever of the other owners were present), the bourgeois, and the clerks ate before anyone else. They were fed in the dining room with the best food the fort had to offer—the best and most varied cuts of meats, bread, soup, and, on Sundays and special occasions, desserts like pie. Almost certainly, French wines were drunk at this "first table": archaeological excavations recovered numerous bottle fragments and some complete bottles of Medoc and champagne. These were symbols of high status anywhere within the United States at the time. Then, as now, drinking wine is a performance with many and varied rituals (de-

canting the red wine or popping the cork on a bottle of champagne, savoring and critically assessing bouquet, color, and taste, toasting the host and guests, and so on). The bottles recovered from the site were actually a part of this performance; a "pipe," or keg, of wine filled two bottles, and the bottles were used over and over again.[34] The message of this performance was that discerning wine drinkers were a breed apart from those who drank merely for effect. The ritual of serving and drinking wine became a powerful link to the more refined cultures of Europe. Of these, none was considered more refined than that of France. As Nietzsche, that prophet of modernity, said, "I believe only in French culture, and regard everything else in Europe which calls itself 'culture' as a misunderstanding."[35] (And Roland Barthes calls wine the French "totem-drink.")[36] Served in the context of this outpost so far from Eastern civilization, the symbolic effect must have been considerably heightened.

Finer ceramics were almost surely used at the first table and at other ritualized partakings of food and drink. Such ceramics were found at archaeological excavations at the fort. While porcelain, the most expensive of ceramics, was not found in great quantity at the fort's archaeological excavations, this does not mean that porcelain was not commonly used by the fort's owners. Time and again, archaeological excavations at historic sites like the mansions and townhouses of the wealthy have yielded few fragments of porcelain. It has been speculated by many archaeologists that this means merely that people have in general been very careful with these expensive ceramics (which are often passed down from generation to generation).

More significant is that expensive and specialized sorts of earthenwares were recovered that could be firmly dated to the time of the occupation of the site by the Bent & St. Vrain Company (as opposed to its later uses as a stagecoach station and as part of a cattle-raising enterprise). Partial archaeological excavations of the fort's two trash dumps in 1976 yielded a good number of artifacts for which dates of manufacture could be obtained because intermittent dumping and burning had "sealed" the deposits.[37]

Table 1 shows the types and associated vessel forms indicated by shards of earthenware recovered from the trash deposits. Two types of earthenware are especially important. The first of these ceramics is transfer-printed ware. Transfer-printing refers to the rather complex technological process by which these ceramics were decorated. A copper plate was etched with a design and inked, the design was transferred first to thin sheets of paper and then from the paper to the clay body of the ceramic. All of this was done by hand, and difficulties could arise at any stage of the process.

The copper plate had to be prepared m just the right way and the ink carefully wiped from the plate, so that it only remained in the crevices of the etching; the thin paper had to be applied to the irregular shape of the ceramic. Transfer-printed ware was expensive, especially during the early nineteenth century, when it was still relatively rare.[38]

Table 1. Ceramic Types From Bent's Old Fort Main and West Trash Dumps Presented By Vessel Form (Hollow Versus Flat) | |||||||

Ceramic Type | Hollow | Flat | Unknown | Total | |||

# | % | # | % | # | % | # | |

Annular pearlware | 32 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 32 |

Lustre pearlware | 44 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 44 |

Spatter pearlware | 91 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 91 |

Floral pearlware | 182 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 182 |

Blue-edged pearlware | 0 | 0% | 34 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 34 |

Transfer-printed pearlware | 33 | 36% | 24 | 26% | 34 | 37% | 91 |

Miscellaneous decorated whiteware (including pearlware) | 0 | 0% | 4 | 9% | 41 | 91% | 45 |

Miscellaneous undecorated whiteware (including pearlware) | 22 | 4% | 27 | 6% | 442 | 90% | 491 |

Decorated graniteware | 0 | 0% | 1 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 1 |

Undecorated graniteware | 3 | 8% | 0 | 0% | 34 | 92% | 37 |

Yellowware | 54 | 75% | 0 | 0% | 18 | 25% | 72 |

Bennington-type ware | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 4 | 100% | 4 |

Green glaze | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 100% | 2 |

Porcelain | 15 | 94% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 6% | 16 |

Unknown buff | 0 | 0% | 11 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 11 |

Total Number | 1,153 | ||||||

John Solomon Otto, like many other historical archaeologists, has found that for sites in the early to mid nineteenth century, the presence of a high percentage of transfer-printed shards in a ceramic assemblage is a reliable indicator of high status, much more so than is porcelain which, as discussed, is hardly ever found in any quantity.[39] Adding to its appeal to the upper classes was that with the fine lines permitted by the technology, one could impart detail enough to tell a real story. These stories were usually of significance to the intended "audience," the market for the ceramic. Certainly that seems to have been the case with the transfer-printed ware associated with Bent & St. Vrain Company, as evidenced by the vignette most frequently depicted on the samples recovered from inside the fort and in the fort's trash dumps.[40]

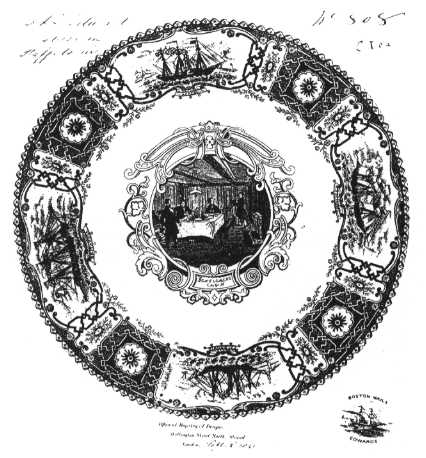

Figure 17.

Registry form for the "Gentleman's Cabin" pattern, part of the

"Boston Mails" series of English pottery. (Courtesy Crown Publishing

Company; from Geoffrey A. Godden, An Illustrated Encyclopedia of British

Pottery and Porcelain [London: Bonanza, 1965], 159.)

This pattern was called by the manufacturer in Staffordshire, England, "Gentleman's Cabin." It is rife with symbols referring to the new culture of the elite: the culture of panoptic control that implemented, among other social phenomena, colonialism. The scene on the ceramic vessels shows the private ship's cabin of a gentleman and illustrates the privacy accorded to individuals in the privileged group (fig. 17). This is the same sort of privacy provided to the representatives of the elite by the second story of Bent's Old Fort. One might bear in mind that the sailing ships

of the early nineteenth century were the technological marvels of their time, on a par in their day with the moon rockets and space shuttles of our own. No other mechanism of that period demanded more precision in its engineering and construction or more competence, both scientific and organizational, in order to be properly employed.

The captain and officers of such a vessel—these might be the four men gathered around the table in the scene—ruled with perfect discipline. Each individual was assigned to his own station, according to his level of competence. The officers were the "natural" masters of the ship, by virtue of their mastery of nature. Nature was harnessed to the ends of this elite group by the use of scientific instruments and knowledge. Gentlemen could use barometers, telescopes, sextants, and other navigational devices. They could read charts, timetables, and almanacs. They could log in careful sequence and detail the events of the voyage, thereby propagating the lessons of their travels to others of their class. The instruments by which all of this could be done are visible or strongly implied by means of the design, which offers us a glimpse into the gentleman's private world, a world of control over nature and lesser men by virtue of his scientific competence. Arranged in a circle around the outside of this central design feature, the view of the cabin, are four large ocean-going vessels, which occupied a position on the cutting edge of maritime technology in the early nineteenth century. The ships are powered not only by sail but also by steam (side paddle-wheels can be seen just below the smokestacks). The names of the vessels are common for trading and whaling vessels of the period: Britannia, Acadia, Columbus, and Caledonia. These ships, however, were the fast mail packets that linked the United States to England.[41] To the owners and traders of the fort, the parallels to their own exploits and ambitions would be obvious. They would surely regard themselves (or at least wish themselves) to be of the same class as the gentlemen portrayed on this ceramic. Also, they considered themselves part of a mercantile, and social, network that extended to England and Europe, a connection symbolized by the representation of the mail packets.

The second sort of ceramic especially noteworthy for its symbolic value at the "first table" and other ceremonious occasions at the fort is provocative not so much by virtue of its cost or decorative motif as by the use to which it was put. Many of the fragments of decorated ceramics recovered from the Bent Period were from tea servings. These included fragments of spatterware and copper lustreware as well as transfer-printed ware. The very ornate copper lustreware was produced almost entirely for tea services.[42] Note in Table 1 that 100 percent of recovered fragments

of "lustre pearlware," which in this case is copper lustreware, along with spatter and floral pearlware, are identified as being of "hollow" form. Hollow forms are cups, saucers, bowls, pots, and other vessels designed to serve drink or food in a semi fluid state. In these cases, the hollow forms were tea servings. These tea sets were associated with special, even formal, occasions. All this is mindful of what Stanley South has called the "British Tea Ceremony." As South states, "the tea ceremony was an important ritual in eighteenth-century British colonial life, relating to status even in the remote corners of the British Empire."[43] South might well have said especially in the remote corners of the empire; the ability to participate properly in this ceremony was a means by which one established one's membership in this colonial force. The ritual both demonstrated and formed a common, mythological "ancestry" and was doubtless employed in that manner at Bent's Old Fort by the elite there.

A "second table" was set for hunters and some workmen. This was the same table previously occupied by the most elite group, but was now set with somewhat simpler fare, including meat, biscuits, and black coffee with sugar. Though those at the second table were members of the entrepreneurial class, it is likely that most would have eschewed the trappings of greater refinement that might have been seen at the first table. Kit Carson on his deathbed asked for "first-rate doings—a buffalo steak and a bowl of coffee, and then bring me my pipe—the clay one."[44] Such were his pleasures, but also the trappings of what he felt to be his proper station. Stripped of effete Eastern conceits, they were appropriate to men of action—plain men with no time for intrigue and politics.

For others at the fort, meals were more bereft of ceremony, and the fare was much simpler. Transients, except for honored guests, were left to their own devices and generally cooked as they had on the trail, although they might be permitted the security of the fort. This in itself was luxurious. After months of danger and uncertainty, where to relax one's guard for only a moment might mean disaster (Plains Indians, even friendly groups, were loath to pass up an opportunity like an unguarded camp), being within this superbly well-defended environment must have been an enormous relief.

Some employees of the fort, too, would not have eaten in the dining room, especially when the population of the fort was at its seasonal peak

of between 150 and 200. Such employees included the families of Mexican workmen, who cooked in their rooms or in the plaza. Here there were

no individual place settings, in fact, there were no ceramics at all. Eating was a collective affair, and tortillas served as both plates and spoons. Mrs.

Magoffin once participated in such a meal, on the trail south of Bent's Old Fort, and her reaction is instructive:

And then the dinner half a dozen tortillas [pancakes] made of blue corn, and not a plate, but rapped in a napkin twin brother to the last table cloth. Oh, how my heart sickened, to say nothing of my stomach, a cheese and, the kind we saw yesterday from the Mora, entirely speckled over, and two earthen jollas [ollas—jugs] of a mixture of meat, chilly verde [green pepper] & onions boiled together completed course No. 1. We had neither knives, forks, or spoons, but made as good substitutes as we could by doubling a piece of tortilla, at every mouthful—but by the by there were few mouthfuls taken, for I could not eat a dish so strong, and unaccustomed to my palate. Mi alma [Susan Magoffin's husband] now called for something else, and they brought us some roasted corn rolled in a napkin rather cleaner than the first & I relished it a little more than the sopa [soup]; this and a fried egg completed my meal.[45]

The revulsion expressed here should not, I think, reflect poorly on Mrs. Magoffin. She was a very, young woman who was in the midst of a private ordeal. She was merely observing and commenting in the manner to which she had been carefully prepared; hers was a social critique that had real social implications. She objected to the unhygienic and unrefined aspects of the meal, and, in doing so, she gave voice to the concerns of her class. (It is interesting, from today's perspective, that while we might see some merit in terms of hygiene to her objection to eating with one's hands, her delicate palate might have deprived her of an important source of nutrition in the Southwestern environment. The inhabitants at Bent's Old Fort never suffered from scurvy in the way common to populations at other western forts, probably because the chilies used so frequently in Mexican cooking were a source of vitamin C, often the only available source in a diet that depended for the most part on meat.) Had Mrs. Magoffin been in better physical condition at the fort, she could have made these same observations there, without personally participating in the meal, by merely looking out the door of her room into the plaza of the fort, where Mexican families were likely to have been cooking and eating in the same way.

Pierre Bourideu has written extensively on the ways in which "taste" is employed as part of a strategy of differentiation. This strategy is used by tribes, in the traditional world, to produce distinctions, one from the other, and thereby to help construct an overarching identity within the tribe. Bourdieu noted that the same strategy is used in capitalistic societies to establish class differences that are the basis for the classes themselves.[46] Bourdieu does not much deal with the ways by which "tastes" are es-

tablished. The dynamics of ritual suggest to me that eating together encourages what then appears to be a "natural" intimacy. It is a repetition of a primal experience. Taste and manners are a kind of communication; if shared, the message is that "we are alike" in what appear to be very, basic ways. This reenactment of a primal experience imbues the foods and objects involved with a value, tableware included. In the above examples, we can see what has been indicated in archaeological studies of ceramic use at historic sites, particularly at plantations.[47] Socioeconomic groups on the lower end of the scale make more use of bowls (if any ceramics are used at all). Eating is a more communal affair. An extreme of this, one might suppose, is the Middle Eastern mensef, in which all eat from a single platter, using only their hands. In the Mexican tradition, tortillas are used to take servings from a communal pot. In New Mexico there were usually no ceramics associated with the consumption of food, except those containing liquid. At plantations, slaves ate stews prepared from less expensive cuts of meat, each receiving his or her serving in a bowl.

Among the elite, however, eating becomes a ritual that reinforces the shared values associated with individualism. Cuts of meat, for example, are prepared individually. Food is served by means of specialized utensils and ceramics. Plates provide a frame for several foods, not mixed together as in a stew but each prepared individually and arranged tastefully. Knowing the "correct fork" marks one as a member of this group. Food is often presented in courses, each course with its own special tableware. Coffee, tea, and chocolate services are examples.[48] Class lines are more firmly drawn in this way. People from different classes become uncomfortable in each other's presence at mealtime, and so segregation is perpetuated. At Bent's Old Fort, in addition to this mechanism of separation, yet another means of social segregation was implemented: There is evidence that charges were made for meals (and for the privilege of frequenting the billiard and bar room as well).[49]

In the variety of ceramic shards described in Table 1 can be discerned the segmentation that is a part of the modern order. Flatware was used to serve portions to individuals, and much of the sample recovered of this ware was decorated with the "Gentleman's Cabin" pattern, a vignette of mythic individualism. Hollowware was used for communal sharing of tea from the same teapot to the cups of individuals in the upper classes, from cooking pots to bowls for the lower. Other hollowware was for specialized activities associated with class. Yellowware shards from the trash dumps appear to represent primarily pitchers and basins. Those in upper echelons used these as a part of a regimen of personal hygiene. At least

in the upper-class homes of the eastern United States at this time, the basins were emptied and the pitchers kept full by servants. And the few fragments of buff-colored ceramics, which do not appear to belong to any of the English or American ceramic types, hint that the practice of eating and drinking from ceramic tableware was spreading at the fort to those who could not afford (or, perhaps, did not want) factory ceramics. The unknown buff ceramic fragments appear to be a fiat form, a saucer or possibly a small plate. It is an extremely soft and Porous earthenware with a thick grayish glaze, and it may have been produced in small quantities locally. An alternate possibility is that the ceramics supplemented the service of the upper echelon.

Thus, the panoptic culture (the culture of modernity, capitalism, and individualism) was propagated by several interrelated means. It spread to the south by the actions of the traders and their allied frontiersmen who acted as "missionaries" spreading the gospel of the new culture primarily by means of exchange with its associated ritual. The fort was linked to eastern centers of power by the surveillance of socially influential visitors, who assured the elite in the East that Bent & St. Vrain Company was advancing the agenda of modernity. This association culminated with the use of the fort as an intelligence-gathering post prior to the Mexican War, and as a staging area as the war began. As Enid Thompson noted in 1973,

The relationship of Bent-St. Vrain and Bent's Fort to the Federal Government and particularly, the War Department is slowly emerging, and it is much more important to our history than has been recorded. It was also more costly to the Bents as a family, and to Bent's Fort, than has been realized.

Charles Bent was an American working internally for the overthrow of the Mexican Government in Santa Fe. His chief St. Louis contact was Thornton Grimsley, and his chief contact in Washington was Thomas Hart Benton. Kearny was well apprised of his 5th column in Santa Fe and army officers were instructed to go to William at the fort or Charles in Santa Fe for help if they needed it beyond legal and proper governmental assistance. In plain language, Charles Bent spied for the American conquest of New Mexico, William Bent led the Kearny column to Santa Fe, and many Mexicans, not least Padre Martinez, were aware not only of the danger, but of the actuality. The records of these activities appear in the secret and confidential letters of the Secretary of War in the National Archives. Protests against the activity appear in Mexican Archives of New Mexico in Santa Fe.[50]

A pre-existing network of Power relations was reinforced and extended by this surveillance. The intensification of surveillance ushered in the most prosperous days of the fort, the "Golden Years" between 1840 and 1846,

which are the focus of today's interpretive program at Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site. During this time, the fort's structure underwent what seem to have been fairly extensive alterations. Fortifications were improved initially during Alexander Barclay's last days at the fort, in 1840, including physical alterations to the building itself. Not long after, the establishment was made more comfortable. The refinement in the way of life at the fort—at least for the elite—would have pleased Alexander Barclay, who complained during his tenure as fort bourgeois that conditions were too primitive for a gentleman of his breeding.

By 1845 the younger Bent brothers, Robert and George, were in evidence at the fort, and they brought with them, for example, the billiard table, which they installed next to a bar they built in the upstairs billiard room. These years also saw an increasing Eastern, particularly a military, presence at the fort.

From 1840 onward, Charles Bent was in frequent communication, through confidential letters, with the United States Secretary of War (these letters are in the National Archives). It is plain from these letters that westward expansion of the country was of mutual interest. Documents in the Archives of New Mexico reveal that Governor Armijo was warning the Mexican government about Bent's Old Fort as a source of subversion by 1840. Authorities in Santa Fe in 1845 made much the same warning to

their central government. In 1745, General Kearny arrived at Bent's Old Fort while carrying out a "topographic survey," which all in the region regarded as an intelligence-gathering mission done with the imminent hostilities in mind. In fact, some of his force were "mustered out" at the fort, and one wonders what became of them thereafter. Bent was by now also sending letters of intelligence to Senator Thomas H. Benton. In 1846, of course, General Kearny was back at the fort with his invasion force. It is important to note that this surveillance network was formed and sustained by various ritual means.

It should be clear that manipulation of meaning through the ritual use of symbolically charged material is a social mechanism used not only by traditional cultures. We can see in the use of the Bent's Old Fort landscape the operation of this very phenomenon, one that affected all who visited the fort, whether they were from the American East or New Mexico, or were members of a Plains Indian group.

A similar use of the landscapes and artifacts of modernity have been noted elsewhere. The work of Mark Leone with the eighteenth-century material culture of Annapolis, Maryland, allows us to observe the manipulation of "sentiment" within a society that is modernizing. The situ-

ation here recalls that which Isaac examined in colonial Virginia, where an elite based in a plantation economy, a group replete with social rituals of hospitality and conviviality, was challenged by an emerging mercantile middle class.

Leone's thesis was that the elite were attempting to maintain control over this society just as it entered the Revolutionary Era by displaying their mastery of natural phenomena in several ways. Important among these were the utilization of objects (and etiquettes) which "were used to observe, study, order, and rationalize natural phenomena": these being, in part, clocks, sundials, telescopes, barometers, compasses, globes, sextants, microscopes, musical instruments, sheet music, and place settings. Such a public use of these devices was intended to establish that this class understood and could control the natural world, and, especially, "modeled daily life's activities on the mechanically precise rules of the clockwork universe."[51] One sort of material culture to which Leone gave great attention is the formal garden of the eighteenth century. It provided a perfect opportunity for the gentry, to exhibit their control over geometry and three-dimensional space.

Leone's thesis has been criticized on two counts. First, it assumes that the formal gardens and the use of scientific devices as he described them worked as intended. Was it a conscious strategy? Did all groups (the elite, blacks, Native Americans, and so on) respond to the display in the same way? We have no certain way of knowing. Native Americans, however, were probably not invited to social occasions at formal gardens. Second, he offers no real mechanism here. His case rested, as did Isaac's, on the fact that the material culture and social behavior he observed arose at a time that also saw broad economic and political changes that seem to make the intentions he ascribed to the elite likely.

I contend that Leone was correct in his intuition that the elite were intending to establish their position with the behaviors he observed. He does not however identify, the most important audience for this performance, which was themselves —not only other members of their elite group, but each individual self To quote Geertz, as done previously, "the imposition of meaning on life is the major end and primary, condition of human existence." Just as it might not be practical, from a pragmatic or functionalist point of view, for the Balinese to wager extravagant amounts on cock fighting, so it may not haste been practical or effective for the elite in Annapolis to expend large sums in constructing formal gardens. But by doing so the Balinese and elite Annapolitans fixed an identity in terms of the ideologies (or mythologies) that gave meaning to their lives.

The activities of the Annapolitans were obviously ritualistic in nature. I suggest that this is the mechanism Leone implied but did not specify. This is especially clear since they so evidently modeled society after the movements of the heavens. Pursuant to this, very basic to the well-developed theories of Mircea Eliade is the notion of a celestial archetype for society in all its aspects. In a book Eliade said he might have called Introduction to a Philosophy of History (actually titled The Myth of the Eternal Return), he stated, "for archaic man, reality is a function of the imitation of a celestial archetype."[52] And, as Eliade noted in various places, the "archaic mind" reemerges continually in the modern world. I agree that this occurs continually and that the "archaic mind" is what we may observe among the eighteenth-century elite of Annapolis.

Characterizing gardens in England from early Georgian times and gardens in Annapolis between 1765 and the end of the Revolutionary Era, Leone said they

were built according to the skillful use of the rules of perspective; in England, they frequently carried a particular message, such as individual liberty, through their iconography and were to so engage a visitors emotional reaction [emphasis mine] by entertaining the eye through the illusions and allusions in them, that the message appeared to have a more real existence by being copied in nature. Such copying could, of course, occur only if the rules were assumed to exist in nature in the first place. The connection between the iconography and nature was created by sustaining the "happy enjoyment of Felicities" that help "clear the oppressed Head" of "Vapours" and "terrors," in other words, through the manipulation of the emotions.[53]

Leone provided here a very clear description of the use of the garden as ritual ground, a place that provides in its every aspect reference to the metapast (the mythology) of emergent capitalism and the ethos of a market economy. Elite visitors to the garden were, according to the comments of such visitors recorded by Leone, engaged by the symbolism. The "manipulation of emotions" is the sentiment of Durkheim.

The construction of Bent's Old Fort conveyed an effective message to both the Plains Indians and the Mexicans just to the south. In its massive symmetry, it proclaimed the arrival of the Americans in the Southwest. But, much more than that, the fort and the surrounding landscape constituted ritual ground of a sort more powerful than the gardens Leone describes or the architecture dealt with by Isaac. The fort provoked affective responses in anyone moving through the landscape. The experience of negotiating the landscape of the fort would be much different for in-

dividuals in each level of the social strata that made up the hierarchy at the fort, and it reinforced that hierarchy every day. In no small part, this difference was due to discrepancies in the ability, to see and be seen. Those who controlled the high ground of the fort were able to impose the discipline of modernity there. The owners functioned socially as a kind of superego; they were in loco parentis for the central authorities of the flowering modern culture in the East. This was the organizing force that acted upon the disintegrating social worlds of the early nineteenth-century Southwest—disintegration that had been brought about by social and cultural dislocations instigated earlier by the East.

Industrialization and the Landscape

Much of what was transpiring in the East at the time Bent's Old Fort was in operation was linked to the rapid industrialization of the early nineteenth century. As the nineteenth century opened, the United States set forth on a course that would establish the country as an industrial nation and an influence in international affairs. The new direction away from an agrarian and toward an industrial society was set with the real finale to the Revolution, the War of 1812. Particularly after the resounding defeat of the British at the Battle of New Orleans, patriotism ran high in the new country. Patriotic motifs and symbolism in art and on utilitarian objects, like ceramics, became popular. Not only were the British defeated in 1815, the United States also placed itself among the world naval powers with its raid on the Barbary Coast, which freed American ships and hostages.

Having established its military potency, the new nation quickly acted to use it to economic advantage. In 1816, tariffs were introduced to prevent the British "dumping" of manufactured goods in American markets, a move that strengthened emerging American industry. The ground breaking for the Erie Canal in 1817 promised a link between the resources of the "frontier" and the industrial and distribution center of New York. This initial grand attempt to stoke the fires of industry and commerce with fuel from the hinterlands was a magnificent success. As the economic benefit to New York became clear, it sparked what has been called a "canal building mania" among other East Coast cities, an obsession only diverted by the railroads when that technology became available a decade later. American industrialization and trade thenceforth grew rapidly, and

apace. To encourage it further, Congress in 1828 passed what was known in the South as the "Tariff of Abominations," which controlled the import of foreign goods. In that year, also, construction began on the nation's first railroad, the Baltimore and Ohio, intended to link the East with the Ohio Valley. This linkage had been a lifelong goal of George Washington, who had encouraged the National Road and who had been president of the Potomac Company, which had built a series of skirting canals along the Potomac River in 1785. In 1828 Washington's dream found expression not only in the railroad but also through the efforts of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company, which intended to build a canal between the Ohio Valley and Washington, D.C., itself. On July 4 of that year, the President of the United States turned the first shovelful of earth in the construction of the canal, proclaiming it to be an engineering marvel matched only by the pyramids of Egypt.