Sentiment and Conquest

In the sense that the fur traders were the "shock troops" of the American assault on the Southwest, as Billington put it, the conquest of the region occurred with stunning speed. Before 1821, Americans were seldom allowed to cross the Arkansas River, and there was practically no intercourse between Mexico and the United States. But after 1821, with Mexican Independence and the possibility. of commerce with New Mexico, American fur traders provided the opening wedge for American influence in the arid plains and green mountain valleys south of the Arkansas. By 1846, General Kearny's army walked unopposed into Santa Fe. There were a few small-scale armed uprisings early on, but within a year any semblance of organized resistance among the erstwhile Mexican citizens had passed. The economy in the region rapidly diversified after this as mining, ranching, and farming replaced the dwindling fur trade in importance. Populations of Americans greatly increased. Roads, railroads, and telegraph lines were constructed. The Native Americans rebelled but were crushed and, by the third quarter of the nineteenth century, were removed to reservations.

This American conquest had depended upon the formation of new alliances and new common realms of understanding between indigenous groups and the Americans. Key Plains tribes had been transformed into allies of the Americans and enemies of Mexico during the period just prior to the Mexican War, and the alliance had been secured by making these Plains tribes trading partners. The role of the Plains Indians in destabi-

lizing New Mexico and, in the case of the Cheyenne, providing a kind of private army to Bent & St. Vrain Company was somewhat tardy confirmation of the Baron de Carondelet's fears about unleashing American influence in the area should trade relations be established by America with the Native Americans. At the same time, resistance to American influence in New Mexico was weakened through the same social mechanism—by engaging Mexican citizens in the trade. Some Hispanics, like Manuel Alvarez, became traders in their own right, traveling to New York, London, and Paris to negotiate more favorable terms for the acquisition of trade goods and cutting out the trading houses in St. Louis from this exchange.[1] Others had become part of an emerging middle class by transporting goods over the Santa Fe Trail.[2] And virtually all New Mexicans were eager for the manufactured goods of the United States and Europe. To a remarkable degree, the Bent & St. Vrain Company provided the agency by which all this was accomplished.

But even this does not tell the whole story. The trading relationship had already wrought fundamental changes to Native American and Mexican cultures alike by the time of the Mexican War. They had been preadapted to inclusion in the emerging global modernity. They were already taking on many characteristics of the high-grid, low-group culture of capitalism and individualism, an ego-centered configuration of society in which each individual must take personal responsibility for manufacturing a viable social identity.[3] Adopting aspects of the ethos of capitalism and individualism was not necessarily immediately beneficial to all individuals in both of these more traditional cultures and often did not fit comfortably with many firmly held beliefs and values. In fact, it set up a cultural tension still not resolved today, especially for many Native Americans. Nonetheless, the cultural dynamics of the time made capitalism and individualism appear highly desirable, perhaps inevitable, and established them as standards that would henceforth be considered natural and normal.

There were essentially two components involved in the transition of these traditional cultures to the new apprehension of life. The first was the destruction of the existing social order. Native American groups had already experienced roughly three hundred years of disease, dislocation, and social disruption. The Sun Dance was formulated in the eighteenth century as an attempt to revitalize a religious structure that then appeared inadequate to the threats to tribal survival. Since that time, dislocation and radical changes in lifestyle had not ceased. For their part, New Mexicans were on the far periphery of the Spanish Empire, generally ignored by the central government, and often living a life of bare subsistence. They

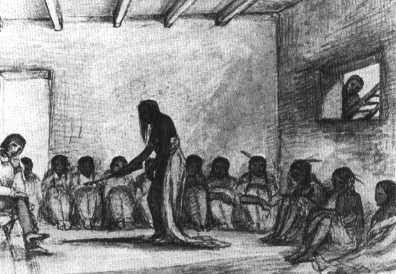

Figure 13.

Drawing by Lieutenant Abort in 1846, showing the use

of a pipe in a ritual exchange in the trade room of

Bent's Old Fort. (Courtesy Colorado

Historical Society, Denver.)

were subjected to incessant raiding by the indios barbaros, raiding often instigated by the new allies of the Plains Indians, the Americans.

The second component was the initiation of trade. Trading relations provided a means by which to remake the fragmented cultures of the Southwest. Trading was done by these traditional cultures, as we have seen, not only for profit and, in the beginning of the relationships, not primarily for profit. Trade was accompanied by ritual that referred to primordial acts of creation. The trade ritual of the Cheyenne, for example, utilized a sacred pipe, the bowl of which was made from catlinite, stone found only in the ancestral home of the Cheyenne. The use of this stone is only one of many references to the creation of the world in the formal calumet wading ceremony. Figure 13 shows a drawing by Lieutenant Abert of an exchange ceremony in the trade room of Bent's Old Fort. The pipe here is almost surely of catlinite. Whether this was a formal calumet ceremony or a more degraded form, such as "smoking over" the trade, the point is that, to the Cheyenne and other Plains tribes, all such exchange referred to a primordial archetype. Those who participated in the exchange, then, were proclaiming a common mythical ancestry and, thereby,

establishing fictive kinship relations. Profit may have been a consideration but was not paramount in importance. Likewise, the reciprocal obligations established by fictive kinship relations may have been useful from a practical standpoint. It seems unlikely, however, given a traditional view of the world, that practical considerations were primary. Most important was the establishment of social relationships. In a traditional world, this is essential to establishing a viable identity. As time passed, the concern for profit grew—and this was the key indication that the Plains Indians had been won over to important aspects of the new ideology. Within the new ideology, profit was a necessary step in establishing a viable social identity.

Understanding how trade brought about this cultural change involves looking at trade and trade goods in a new way. The new perspective recommended here is one that searches for the meaning attached to trade objects, meanings that are assigned through formal or fugitive ritual. In subsequent chapters, we will look also at how meaning is attached ritually to other sorts of material culture, including the landscape itself, and how the cultural assumptions and values thereby propagated advanced the culture of modernity in the Southwest.[4]