Ethnographic Treatments of the Sun Dance

Leslie Spier's 1921 study of the Sun Dance has long been regarded as the benchmark work for the ceremony. He linked it most closely with the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Oglala Sioux but asserted that it was practiced in modified forms by eighteen Plains tribes. Schlesier termed the Sun Dance an "anthropological invention," arguing that these tribes actually performed different ceremonies that shared certain common attributes. He also considered the term Sun Dance to be a misnomer, preferring the Cheyenne word for the dance, Oxheheom, meaning "new life" or "world renewal" ceremony.[9]

In the general anthropological and popular literature, nonetheless, the Sun Dance is regarded as the central ceremony for the Plains tribes. It is perhaps because the most well-known aspects of the ceremony resonate so strongly with basic modern cultural assumptions about individualism and individualistic renewal (such as the need for a personal vision and the acceptance of suffering to achieve it) that it is likely that it has been studied and described as much as any "primitive" ritual. There is also a vast popular and academic interest in the tribes that practiced the ceremony, particularly the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux. Numerous ethnographies have been written about the Cheyenne alone.[10] Some large libraries have almost 1,000 entries in their bibliographic files under the heading "Cheyenne."

And yet, there is no agreement about all aspects of even the Cheyenne Sun Dance. The use of tobacco, for example, is mentioned by some ethnographers and not by others. The precise timing of the Sun Dance is also unclear in these ethnographies. Most mention that it is usually held in July or near the summer solstice, but some place the time of the ceremony later. There are many reasons for these discrepancies and uncertainties. Observers often record only what they have decided beforehand to be important and may not mention aspects that are of small interest to them. Also, informants may be vague or purposely misleading. A woman involved in the preservation of Cheyenne traditions told me recently not to put too much credence in the work of ethnographers, including Grinnell (the most famous of Cheyenne ethnographers), because the Cheyenne sometimes

found it amusing to lead ethnographers astray.[11] Most important, rituals change even though they must purport to represent the unchanging. It is likely that no two Sun Dances were ever performed in exactly the same way. Enough ethnographic descriptions of the Sun Dance have been done with sufficient precision to record the fact that they do change.

Nonetheless, even a cursory description of the most basic elements of the Cheyenne Sun Dance is sufficient to illustrate several facets of the social mechanism of ritual. The ceremony was sometimes called by the Cheyenne "renewing the earth" or the "new-life-lodge" (terms that again hint at a sacred model for both topography and architecture). Many participated in the various roles demanded by the ceremony. The most important of these roles were held by the priests, the sponsor, and the few young men who desired a vision that would guide them through the balance of their lives. These young men, as I argue elsewhere in this book, were suffering from anomie; they were in distress because they could not find a suitable place for themselves in their society. They sought a personal rebirth by participating in the rebirth of the Cheyenne.

Simply attending was a kind of participation. The Cheyenne shared a language and many habits of behavior, but during most of the year were not together. They went about their nomadic rounds in bands made up from as few as one to several extended families. These bands were knit together by the affiliation of individuals in the bands, or sometimes of whole bands, and with clans and special "societies," especially warrior societies. Clans and societies convened for rituals, societies for ritual and ritualistic behaviors (warfare and raiding being among the most important of the latter). The Sun Dance, however, was for the Cheyenne as a whole, and acted powerfully to maintain the Cheyenne as a whole.

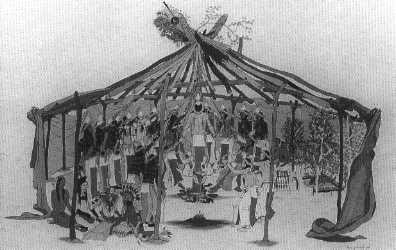

The construction of the Sun Dance lodge (the ceremony is also known as the medicine lodge ceremony) reenacted the creation of the world. Searching for the Sun Dance pole, counting coup on the tree that was to serve this purpose, and attaching the medicine bundles and offerings to the tree was the first great spectacle of the ceremony. As Donald Berthrong recorded it, one of the tribal chiefs would address the tree, saying words such as these: "The whole world has picked you out this day to represent the world. We have come in a body to cut you down, so that you will have pity on all men, women, and children who may take part in this ceremony. You are to be their body. You are to represent the sunshine of the world."[12]

The "new-life lodge" was then constructed. The altar in the lodge represented the whole of the earth. On the altar were the paramount things of the earth, including a buffalo skull, strips of sod to represent the four

cardinal directions and the sun, and the foliage of useful vegetation such as cottonwoods and plum bushes. The lodge itself referred to the heavens, and appropriate designs were applied there. Bundles of vegetation were tied to the center pole, and dried buffalo meat was secured to one of the bundles by a broken arrow. To this, a rawhide image of a human was also attached. At least one ethnographic account records that tobacco was attached to the center pole. Dancers were painted five times during the fifth and sixth days of the ceremony with colors (yellow, pink, white, black) and designs (the sun, moon, flowers, plants) that referred to the blessings of the earth.

It was also at this time that the young men underwent the self-torture that they had vowed to endure in an attempt to gain special favor or relief from the gods. Two skewers, variously reported as being bear or eagle claws or made of wood, were hooked through the flesh of a man's breast or, less frequently, through the flesh of his back. At times the man was hoisted by a rope suspended from the central pole, the sun pole, where he hung until the flesh tore away (fig. 6). Or, he might remain on the ground, pulling against skewers attached to the sun pole until his flesh tore. In some cases, when a man was suspended for a long time and the skewers held fast, he might attach the skewers by means of thongs to buffalo skulls, which he would drag over the plains until they caught on some obstacle and he broke free. This ordeal was preceded by fasting, meditation, and sleep deprivation, which generally produced a state of religious ecstasy and visions in which a totemic spirit advisor appeared, one that would thereafter be the man's spiritual guide. The totemic advisor, of course, would come from the tribe's cultural stock of mythological figures, and so the man's personal vision would be intertwined with that of his culture.

Attendance at the Sun Dance was compulsory for every adult male, but it is likely that everyone in the tribe attended. It was, after all, a spectacle that evoked a considerable affective response in its audience. This is an essential part of ritual, as Emile Durkheim established many years ago; ritual must evoke an emotional response, a shared "sentiment" in Durkheim's terms, that, by being shared, binds together participants and spectators.[13]

Considerable effort and commitment of resources went into organizing a Sun Dance, and this required a sponsor. In pre-reservation days, a man might pledge to sponsor a Sun Dance if he survived some imminent danger, most likely danger experienced during a raid to acquire horses or as a result of the tensions that arose following such a raid. Later, a sponsor might be a person expressing gratitude that a member of his or her

Figure 6.

"Sun Dance, Third Day." (Detail from a painting by Dick West;

courtesy Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma; reported in Donald J.

Berthrong, The Southern Cheyennes, copyright 1963 by the University of

Oklahoma Press.)

family had recuperated from an illness or escaped from a physical threat. The sponsor could be either a man or woman but had to have access to considerable resources. Prestige accompanied sponsorship. The sponsor was the principal participant of the Sun Dance, being regarded as more important than those who went through the self-torture. The sponsor became known as the "reanimator" of the tribe, the person through whom the tribe was reborn. In subsequent years, the sponsor joined an elite fraternity of Sun Dance sponsors, who were co-owners of the Sun Dance medicine bundle. Thus, the sponsor was assured an important role in future ceremonies. If the sponsor were a man, an added requirement of his sponsorship was that he pledge his wife to the ceremonial grandfather during the preliminary rites of the Sun Dance. If a man's wife was unable to carry out this role for some reason, or if a man had no wife, he had to find another woman to fulfill this role. Often this was a sister.

All the bands of the Cheyenne tribe were present for the Sun Dance. The camp for this occasion was laid out in a carefully prescribed way. It was always located on the south bank of a stream, with the clan camps ordered in a traditional sequence and forming a circle that was often a mile in diameter. An opening in the circle always pointed east. The six

Cheyenne military societies camped at prearranged locations in the camp circle,[14] and to assume a position different from a traditional one was considered highly meaningful and threatening to the order of the tribe.