Preferred Citation: Fernandez, Renate Lellep. A Simple Matter of Salt: An Ethnography of Nutritional Deficiency in Spain. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2d5nb1b2/

| A Simple Matter of SaltAn Ethnography of Nutritional Deficiency in SpainRenate Lellep FernandezUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1990 The Regents of the University of California |

To

Enrique Carrasco Cadenas

1934 head of the department of dietary hygiene

National School of Public Health, Spain

Preferred Citation: Fernandez, Renate Lellep. A Simple Matter of Salt: An Ethnography of Nutritional Deficiency in Spain. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft2d5nb1b2/

To

Enrique Carrasco Cadenas

1934 head of the department of dietary hygiene

National School of Public Health, Spain

Prologue

This book is the fruit of a project concerned with the effects of delay and denial in human affairs. Anthropology, and the fieldwork that lies at the heart of it, is rarely an easy profession to practice, and a concern with delay and denial brings it more than its share of resistance and frustration. Those who participate, willingly or not, in a system of delay and denial—which has had unfortunate or grievous consequences in the lives of others—are not eager to have this implication of the lives they lead or the professions they practice pointed out to them; yet this is what I have tried to do here in a "simple matter of salt." All the more season, then, to acknowledge the help and support of those who, because of their own possible involvement, and, thus, not easily seeing what I was about, may have felt a natural resistance to the argument. What I advocate, an early preventive use of a simple remedy, and what I document, one country's long delay in getting around to iodizing salt, is worth pondering everywhere, whatever one's possible involvement in whatever system of neglect and denial.

Iodized salt, we should recall, had been introduced to stunning effect on a massive scale in both Switzerland and the United States in the 1920s. E. Carrasco Cadenas, a Spanish public official of the 1930s had advocated, on the basis of his own pilot studies in villages of northern Spain, similar action, but his intelligent and strenuous efforts failed to bring about the desired result in any timely way. This failure in one of Carrasco Cardenas's major projects must have been a great disappointment to him. He died young

at the end of the Spanish Civil War and it is to him and to the memory of his early efforts that this book is dedicated.

Why the simple preventive measures he advocated failed to take root is what this book explores. It is about the social, cultural, and political obstacles that create confusion and disinformation about diseases that—whatever the lifeway of an afflicted community or the belief system of a relatively unafflicted middle class—may be preventable.

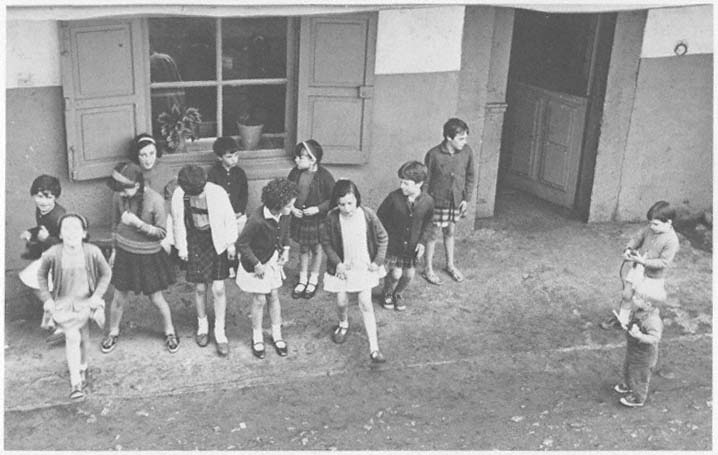

Though this book is critical of some aspects of the medical establishment and of some of its narrow definitions, I would like to thank four Spanish physicians for their specific support and for their freedom from "established opinion." First of all, country doctor Manuel García Pérez of Caso, for showing me, as part of a project reminiscent of that of Carrasco Cadenas, schoolchildren he correctly believed were needlessly suffering iodine deficiency, thereby letting me know that my concern was well founded and that the endemic was not limited to a single village. Second, hematologist Joaquín Fernández García of Oviedo, who has a strong concern for the people of Escobines; I am grateful for the privileged "medical rounds" he gave me in that village, removing the doubts—in the face of wide medical denial—I had learned to entertain about the reality of the Asturian endemic. Third, endocrinologist Francisco Díaz Cadórniga, chief of endocrinology at the Hospital de Nuestra Señora de Covadonga de Oviedo, who gave me a historical perspective on preventive efforts in Spain and kept me in touch with new developments. And, last, investigative endocrinologist Francisco Escobar del Rey of Spain's CSIC, who added to that perspective, made important references available to me, and exemplified the citizen-scientist—a scientist active at once in high-technology investigation and in low-technology prevention.

Then I would like to thank the Spanish friends who have repeatedly, despite what must have appeared an obsessive inquiry, made me feel so welcome in Asturias: the family of Luis Días Muñiz in Oviedo and Celina Canteli and Julia Fernández and their respective families in Arriondas. I would especially like to thank Juan Noriega of Cangas de Onis for insisting that he, as a friend, hone my Spanish so as to more effectively take my inquiry beyond the confines of the village.

In the United States, I would like to thank the faculty of Rutgers

University, where the first version of this book appeared as a doctoral dissertation. First of all, I thank endocrinologist Louis Amaroso of New Jersey's School of Medicine. He shared my vision and kindly tutored me through the intricacies of the thyroidology I had to learn in order to link bodily pathology to the concept of a socially constructed disease. I thank Lionel Tiger of the Department of Anthropology who directed the dissertation. I thank the independent scholars of the Princeton Research Forum for the generous feedback they gave me in the spirit of an intelligently critical public. I thank Carole Counihan, a colleague and friend, for having offered me over the years a professional forum in which to explore my ideas, thereby giving my inquiry a badly needed sense of legitimacy. I thank Paula Ardehali, who has enriched our friendship by repeatedly offering wise editorial comment.

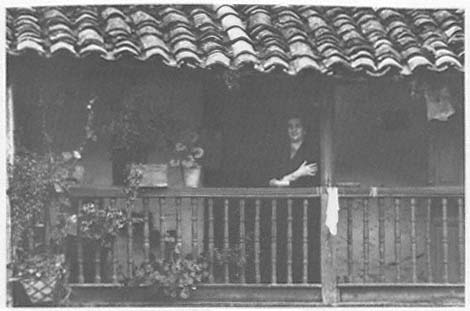

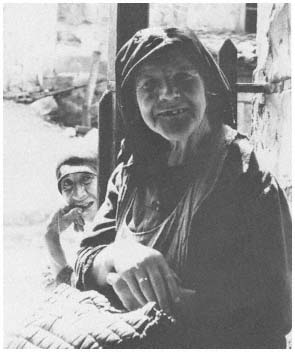

And, of course, I thank the villagers of Escobines who, since this is a study of pathology, will be thanked only by their first names (this also conforms to village practice); MariCarmen, Rosa, Carmina, Cheli, Floripes, Ludi, Rosaura, Ramira, Nati, Filomena, Pili, Jacoba, Luisa, Argentina, Chauri, Jesusa, Gene, and Socorro. Nor can I overlook the urban friends whose narratives of their own thyroid disorders have given me important insights: Susi, Milagros, and Celinuca. If the names of men are missing from this list, it is because iodine deficiency disorders, except where the deficiency is very severe, cosmetically affect mostly women. At a more profound level, as this study shows, men and boys are affected by it as well, as, indeed, are entire communities and regions. I thank them for having put up with this intrusive inquiry into the stigmatized condition so endemic in their village and for always receiving me and my family warmly.

Last of all, I thank my family, who have remained with me over the ups and downs of this longitudinal study. My concern with the dwarfed, deformed, and retarded must have seemed like an obsession to them, until they came to realize that it was in the service of better understanding the obstacles to prevention. I thank Andrew for giving me, when he was very young, a very personal reason for resisting denial; and I thank him for later introducing me to my Apple (only with it was it possible to write and rewrite obsessively). I thank Luke for periodically introducing a bit of sinister humor to the project. I thank Lisa for giving me hope, for ex-

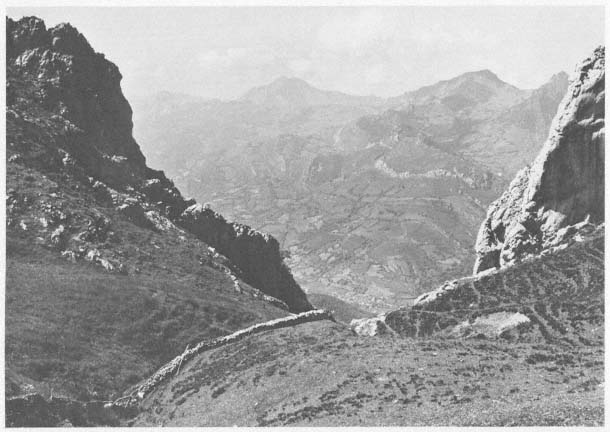

terminating passive verbs, and for, several years ago, editing seven very crude chapters into a manuscript that could subsequently be approached by harsher critics. I thank Jim for bringing me to the field and having me espouse anthropology, inseparable from him. We are now jointly at work on the ethnography of this valley of cattle keepers and miners. Under the grants that he was initially able to get, we went to the field as a family, gathered the baseline materials for our diverse studies, and established the relationships that have continued to draw us back to Asturias over a twenty-five-year period. Our joint, and very strong, attachment to Asturias and the friends we have there—in village, town, and city—give an unusual temporal depth to this study. When in the mid-1960s I first came to this beautiful mountain landscape, goiter was everywhere and taken for granted as if it were part of that landscape. Now in the 1980s, major efforts are being made to eradicate it. In a small way, I can claim to have been a part of that change of attitude. This book is about that change in an Asturian mountain valley, set within a far larger problem of delay and denial in the perception and treatment of affliction.

R. L. F.

CANGAS DE ONIS, ASTURIAS, SPAIN

NOVEMBER 14, 1989

Chapter 1

Introduction

Simple Measures and Major Obstacles

A simple, timely action in the 1920s—the iodization of ordinary table salt—would have made the writing of this book unnecessary. But people in iodine-deficient regions of Spain needlessly suffered until the early 1980s, and in many regions of the globe continue to suffer, the chronic and often degenerative consequences of endemic goiter and cretinism. These are the two most well-known manifestations of the set of diseases coming to be known as iodine deficiency disorders, or IDD. A nutrition deficiency disease, IDD is manifested in a wide spectrum of afflictions that iodized salt is effective in preventing.

While the iodization of salt is a simple matter, the reasons for the failure to adopt this measure are complex. It is my task here to contribute to our understanding of health systems and medical care by explaining the complex of reasons that account for such inaction or delay.

The number of victims needlessly afflicted with IDD in Spain over these sixty years is not, even in that country, small. Over this time span, we conservatively estimate at least 10 million Spaniards to have been at risk of IDD; 50,000 have been sufficiently afflicted to have sought treatment.[1]

But inaction and delay have much wider—indeed worldwide—implications. For the failure to take the preventive action here examined is, in respect to IDD and a host of other preventable diseases, repeated over and over again, year after year, in country

after country. According to the most recent United Nations estimate, 800 million people around the globe are at present at risk of IDD (Hetzel 1989). This "simple matter" has very large implications indeed.

We have long known how to prevent the conditions, endemic goiter and cretinism, discussed in this work. Likewise, we have long known how to prevent other nutritional diseases such as pellagra and scurvy, obesity, adult onset diabetes, or the heart disease associated with a high cholesterol diet. More recently, we have learned how to control infant diarrhea with an extraordinarily simple measure also involving salt, but we have managed to propagate that technique to only one-fourth of the world's parents in need of it. We have also long known how smoking is associated with lung disease and how poverty and teenage pregnancy are associated with low infant birth weight, retardation, and other birth defects. But, as in the case of iodine deficiency in Spain, using our knowledge of prevention straightforwardly and to maximum effect has not been easy.

Take the example of our own society. It is our paradoxical tendency to spend very large sums on therapeutic high-technology intervention while neglecting to take preventive action. While the case reported here happens to have taken place in another country, the lessons that can be drawn from it are more widely applicable. The lessons are applicable on a global scale.

Today's newspaper headline, as I write this introduction, offers an instance of these problems:

HOSPITALS OVERWHELMED AS POOR IN NEW YORK CITY SEARCH FOR CARE

At its roots [it is] a crisis of a public-health system that regularly produces advances in medical procedures but cannot adapt itself to meet the most basic health needs of the poorest and weakest. . . . The crisis will not be solved by more beds. Unless there is a concomitant expansion of other services we will simply perpetuate a system in which expensive hospital-based technological interventions are substituted for more appropriate primary-care services.[2]

Here at home in the midst of our greatest city, in a cultural context different from the one reported in this book, is the problem we examine: the misdirection and misapplication of high-technology medical knowledge at the expense of low-technology primary care and prevention. The result of such misapplication of knowledge and resources is needless affliction.

Compared to the dramatic applications and cost of high-technology therapeutics, matters having to do with "primary care" may seem uninspiring. Typically, they involve education, immunization, monitoring and social support, and dietary or behavioral adjustments. It is not the stuff of high drama. Nor are such matters likely to seem the answer when, as in the American case, an infectious, life-threatening disease such as AIDS befalls us. Yet we continue to learn only belatedly, after years of affliction, how crucial preventive measures can be. Indeed, in the case of AIDS, they, for the moment, offer the only hope.

Most often, such low-technology measures are the most effective means of preventing or limiting the spread of chronic, endemic, and nutritional diseases. These, as in the case of iodine deficiency and other kinds of easily preventable disorders, assail hundreds of millions routinely as a part of daily life. Whether for our own sake or for the sake of the vulnerable millions in the less affluent parts of the world, we need to understand better the obstacles to prophylactic thinking and prophylactic action. By analyzing a case history of endemic goiter and cretinism, this work seeks to contribute to that understanding.

The Focus of this Study

In this work, I seek to explain inaction—the sixty-year delay in eradicating endemic goiter and cretinism in the village of Escobines and the parish of El Texu, a set of mountain communities in Asturias, a province of northern Spain. The knowledge gained in these mountain communities is set within the larger Spanish context and ultimately within a global context.

The case examined here illustrates, as I say, the wider phenomenon of inaction—the passive toleration of noninfectious, readily preventable diseases, chronic or endemic, that seem to exempt urban Westerners from their threat. Hence, this study is concerned with two larger issues: the diffusion of prophylactic techniques and knowledge and the generation of political will to employ that knowledge effectively.

There are many other conditions that merit the kind of attention given here to endemic goiter and cretinism, or IDD. Among these conditions are infant malnutrition, smoking, alcohol consumption, and overeating. What we learn of the twentieth century's passive toleration of IDD can help us understand these broader problems.

The iodine prophylaxis that at a mass level is capable of safely and effectively preventing endemic goiter and cretinism became feasible in the early 1920s. Knowledge of it came to the attention of the medical community, heads of state, and the American public during the peak years of the "prophylactic era"—from about 1920 to 1934. It was an era during which prophylactic programs were initiated in Switzerland and the United States and the virtues of iodine prophylaxis were widely discussed in popular literature as well as in professional journals.

Popularly, it was well known that Asturias and many other mountainous provinces of Spain had for many generations been afflicted by endemic goiter and cretinism, but it was during the prophylactic era that knowledge of these endemic disorders in Spain was inserted into the national and international medical record. The breadth and intensity of these endemias was delineated by Gregorio Marañón (1887–1960), Spain's most prestigious twentieth-century clinician. Marañón described their distribution first to his colleagues in the Royal Spanish Academy of Medicine and later to the first International Conference on Goiter and Cretinism (Schweizer Kropfkommission 1928).

The Swiss conveners of the conference offered a forum for presenting the results of pilot iodization programs and sought an international consensus to urge adoption of Vollsalz, "full" or "complete" salt. Marañón, however, rejected iodine prophylaxis for Spain, arguing that it was too specific a remedy for the wide spectrum of affliction he had seen in the endemic areas of his country. Instead of iodization, he favored broad economic development—an approach the Swiss considered a "grand detour" (Ein grosser Umweg ; Hunziker 1924). Regardless of his posture at the conference, at home, Marañón continued to be regarded as the national authority on endemic goiter and cretinism. It was he, after all, who had represented Spain in the international arena and singlehandedly imported endocrinology into Spain (Glick 1976). Since Marañón was also a man of letters and a political statesman who consorted with the king and later with Franco, his stature was such that, had he seen fit, at any point in his career he could have initiated iodine prophylaxis, whether specifically in the several regions of Spain designated by him as endemic or in the nation at large.

Marañón's overriding interest in curative rather than in preventive medicine may explain his failure to endorse iodine prophylaxis, but his medical and social authority, extending well beyond his death in 1960, meant that without his endorsement no prophylactic programs in Spain could get under way on a mass scale. As long as his views dominated Spanish medicine, any attempts at mass iodine prophylaxis faced prohibitive inertia at the national level. Only in 1984, a quarter century after his death, did regional health authorities initiate large-scale iodine prophylaxis in afflicted areas. This is the inaction (it can be seen as a delay only after the initiative gets under way) I seek to explain.

But any adequate and, indeed, useful explanation of inaction in regard to a major problem of public health has to reach beyond a single powerful actor. It must examine the medical, historical, social, economic, and cultural factors—in this case, both in Spain and abroad, both domestic and international—that create the social fabric of ignorance and indifference underlying inaction on any particular frontier of health. In other words, though Marañón was undoubtedly a powerful actor, he was nevertheless acting within a context that both influenced him and supported inaction.

Single individuals and local circumstances, as we shall see here, have created formidable and nationally specific obstacles to prophylaxis. These alone, however, cannot explain the globally widespread delay in implementing iodine prophylaxis. This is no minor matter. While iodine prophylaxis is generally regarded as the most cost-effective, mass-level, public health measure known, its benefits have not yet reached the already mentioned 800 million people around the globe (Hetzel 1989) who are still experiencing the debilitating physical, mental, social, and economic effects of endemic iodine deficiency (Matovinovic 1983:369). In this sense, the close examination of one case can throw light on the general problem of inaction, whether it concerns IDD, other conditions of dietary deficiency or overnutrition, or nondietary but widespread practices, for example, atmospheric pollution and depletion of ozone, affecting the quality of our lives.

Precedents

It is easier to examine events that have happened than those that have not. Nevertheless, some authors have addressed the elusive

subject of inaction. Matthew Crenson (1971) made a start in explaining inaction by examining the widespread hazard of air pollution to large populations and the concentrated interest of a few polluters to do nothing about it. Daniel Koshland (1987), among others, addressing himself to a wide spectrum of scientific, technological, and public concerns, has drawn attention to the need to find ways to weigh the uncertain costs of inaction against the certain costs of intervention. Most recently, And the Band Played On (Shilts 1988) offered a multistranded explanation of the exasperating delay attending the American response to AIDS. A variety of analyses on other fronts have dealt with the failure to withdraw support, for example, for the cultivation of tobacco, for the construction of houses on floodplains, or for the promotion of infant formula in inappropriate contexts. All of these accounts address the problem of inaction. Further studies should identify principles that underlie the reversal of hazardous passivity.

As for goiter and cretinism, I am not the first anthropologist to work in a community where IDD is endemic. Cultural anthropologists, at least traditionally, have been attracted to studying isolated people residing in mountainous areas difficult of access. As will be seen later, geologic factors alone tend to make iodine scarce in such regions, producing disorders in those whose food is exclusively of local origin. The anthropologists who have studied the culture of people residing in regions deficient in iodine have, with few exceptions, remarked on the presence of these endemias; but they have considered the endemias as incidental, as having little bearing on the society and culture they have come to observe. Netting, working in a classically alpine region of IDD, and author of an otherwise exemplary ethnography (1981), illustrates this incidentalist approach.

Other anthropologists, using a contrasting approach, have drawn attention to changes that have introduced goiter and cretinism to peoples previously unafflicted with IDD. Andrew Vayda and Henry Kranzler (1977) have shown how the disruption of traditional trade routes supplanted customary salt (inadvertently rich in iodine) with ordinary uniodized trade salt, imposing IDD on a New Guinea people among whom goiter and cretinism had been unknown. Georgeda Buchbinder (1977) also reported on a recent eruption of endemic goiter in New Guinea which resulted from the

displacement of people from their highland home into a yet higher, previously uninhabited valley. These publications, combined with the alarming visual and quantitative material produced by D. C. Gajdusek (1975), set the stage for the initiation of iodine prophylaxis in New Guinea.

So far, the most comprehensive study of an endemic community is that by Lawrence Greene, a physical anthropologist who in his field study collaborated closely with Rodrigo Fierro-Benitez, an endocrinologist from Ecuador. Greene investigated the psychological and social effects of iodine deficiency on Andean villagers (1973, 1977a , 1977b ). Because his work was comparative both within and across villages, he was able to isolate the effects of endemic IDD from a generalized backdrop of protein-calorie malnutrition. In a medical experiment, he compared the performance of a set of controls—children whose mothers prior to conception had received prophylactic injections of iodine—with the performance of children of the same age and in the same village who had not received this uterine benefit. The latter group's performance on conventional psychological tests and on tests especially devised for this culturally specific situation was, in contrast to that of the iodized group, alarmingly low.

The endocrinologist compared, in a natural experiment, two nearby Indian villages: a village free of IDD (because it had access to nearby unpurified rock salt rich in iodine) with one endemically afflicted (Fierro-Benitez 1968). This study revealed the neurological and behavioral limitation that was an integral part of life in one village—affecting the distribution of employment, migration opportunity, labor assignments, food, comforts, and affection. He went on to show the several effects of widespread behavioral limitation, how it generally lowered the standards and expectations villagers had of each other and created hierarchies in the village, and how the burden of behaviorally limited individuals in the villagers' midst affected, in the larger society, the reputation of all the members of the afflicted community. This collective disrepute, in combination with a long history of exploitative and extractive domination, made the villagers docile and facilitated their exploitation by members of the larger surrounding mestizo society.

Greene did not argue, and on this point he was clearly misunderstood (Vayda 1979), that iodine deficiency caused social and

racial stratification. He and his colleague did, however, argue that widespread behavioral deficit stemming from iodine deficiency served vested interests. For just as IDD produces defects in individuals and, consequently, hierarchies among villagers, it also reinforces social stratification already existing at local, regional, and national levels. In other words, nutritional deficiency works systematically to make all the members of an endemic community—regardless of the degree of affliction in any particular individual—more vulnerable to exploitation.

The pervasive effects of iodine deficiency on a community were also observed by Margaret Mead. Unlike Greene, however, she did not initially set out to inquire into iodine deficiency or into any culture of affliction. Rather, Mead's cultural concerns impelled her to select a particular Balinese village for the observational advantages afforded by unfinished constructions—a village where the walls dividing domestic from public space were left incomplete. Only after having worked in this "unfinished" village for a time did Mead recognize a pervasive underlying iodine deficiency, especially manifest in hypothyroidism. This, she reasoned, was the underlying cause of the lethargy and slowed mentation expressing itself in unfinished construction. Long after completing the fieldwork, she argued (1977) that hypothyroidism's continual sapping of villagers' energies offered her the opportunity of observing the elaborate Balinese culture stripped down to its essential elements.

Neither prophylaxis nor the obstacles to it were Mead's concern. She did, however, notice that those accepting the prophylaxis she offered were outsiders who had married into the village, while those born and raised locally rejected it. Indirectly, this suggested that a lifetime of habituation to pervasive behavioral defect may set up local obstacles to prophylaxis.

Four decades after completing the Balinese fieldwork, Mead recommended, despite perceiving the drag of iodine deficiency on these Balinese villagers, that the proper focus of anthropological investigation should not be the individuals or communities succumbing to environmental or nutritional stress but rather the individuals and communities apparently impervious to it (1977:265). Mead maintained that her opinion spoke for the unexpressed opinion of the majority of anthropologists, presumably those interested in culture.[3] This majority feels itself uncomfortably "racist" drawing

attention to morphological and behavioral limitations it considers itself unable to ameliorate (1977:262). Her admonition seemed for a time to place work such as Buchbinder's and Greene's beyond the pale of "normal" cultural anthropology.

If Mead's view ever represented the view of a broad segment of anthropologists, it has now been transcended. Anthropologists have recently shown how society and culture play important roles both in producing and alleviating morphological and behavioral limitations (Scheper-Hughes 1979; Laderman 1984; Kleinman 1980; Kleinman and Good 1985). This case study follows that tradition. It expresses my belief that ignoring stigma and disrepute or treating morphological and intellectual features—such as endemic retardation and bodily deformity that quite possibly have their genesis in conditions that can be ameliorated—as incidental to culture lends support to inaction.

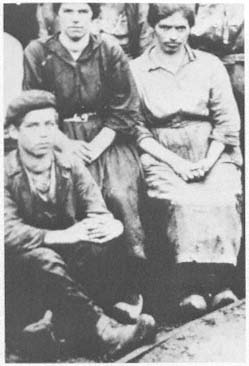

How this Investigation Emerged

I did not choose in advance to investigate the problems of affliction and inaction. Rather, they confronted me in the field after the field site had been chosen, on terrain characteristically that of the social or cultural anthropologist. A broad-scale ethnography was the object of research. The terrain consisted of small mountain communities variably touched by modernization, industrialization, and bureaucracy. In these communities, I, my husband, James W. Fernandez, and our children witnessed, over the course of a longitudinal study, rapid social and cultural change brought about by the shift of agropastoralism to coal mining. This shift got under way during mid-century but increased its tempo during the 1960s, as we were beginning our research. We focused our work on one particular village, Escobines, comparing it to other nearby villages, where the economic shift was proceeding at a different pace. We have presented several facets of that work (J. W. Fernandez 1976, 1977, 1984a, 1984b, 1985, 1986a, 1986b, 1988a, 1988b, 1988c ; R. L. Fernandez 1979, 1980, 1985, 1986, 1987a, 1987b, 1987c, 1988, 1989a, 1989b ; J. W. Fernandez and R. L. Fernandez 1976, 1988).

The documentation and analysis of inaction on the prophylactic front came only gradually to be one part of that larger project.

Early during our series of field visits, I took notice of the goiters much as the incidentalists had done before me. Then I became increasingly aware of the pervasiveness of less obvious disorders. These brought forth my concern for the social aspects of affliction. I speculated that these diffuse afflictions, like goiter, were related to iodine deficiency, but local medical and health personnel denied any connection between goiter (which, they maintained, was not endemic but idiopathic) and these more diffuse afflictions. Moreover, since goiter was said to be "declining of its own accord,"[4] these professionals expressed no interest in my preoccupation. Since I was for a long time unprepared to imagine that physicians could not know about iodine prophylaxis, I interpreted their two-fold denial as expressing political opposition to prophylaxis. Whatever the basis of those denials, their response made it clear that as long as the Franco regime remained in power, an outsider could not hope to investigate political obstacles to prophylaxis.

Franco's death in 1975 put an end to his four-decade regime and inaugurated a period of accelerated political change during which the political obstacles to prophylaxis that I had imagined seemed to recede. Yet, since goiter, though declining, appeared still to be endemic and prophylaxis did not get under way at the close of this era, I was forced to enlarge my tentative political hypothesis and look for others as well. I learned then that the biomedical community abroad attributed this inaction to underdevelopment.

But underdevelopment could hardly explain the IDD and non-prophylaxis before me. Asturias, after all, was a well-developed economic region with roads, tunnels, mines, and harbors; with universal schooling and a high literacy rate; and with low infant mortality.

The extent of development had been revealed to me by our longitudinal study, which in many ways provided a rich backdrop for probing further into the puzzle before me. Unlike Mead's villagers, these Austurian village women were seeking remedies: they were taking vitamins for "thyroid," seeking goiterectomies, and exposing their glands to nuclear medicine, paid for by the state. Yet, and here was the nub, they did not seem to know that they were suffering needlessly. No villager knew of the existence of iodine prophylaxis. And as I inquired further, it became clear that middle-class urbanites and the vast majority of Asturian physicians also did

not know of its existence. I was taken aback by this specific ignorance in the midst of such high-technology medicine. I had thought that in medical circles, iodized salt was universally known as a cost-effective prophylactic.

This revelation of my own unexamined assumption prompted me to inquire into the complex of obstacles that exist in the larger contexts of national and international life, both in Spain and beyond. Pursuing this complex of obstacles, I came to recognize and feel part of an old anthropological tradition that, long in abeyance, was experiencing a revival at the turn of the 1980s. That tradition considers morphology and physiology a legitimate and central part of holistic anthropological inquiry (Konner 1982). Study of the interplay, in the case before me, of geology and chemistry, the human body, medicine, history, economics, and politics, land, and culture might answer questions that discrete biological, cultural, or medical inquiries—narrowly construed—might never answer.

The Diabetes Study Group of the American Anthropological Association, for example, has employed this holistic approach for some time. Why, some of its members have asked, are certain populations like the Papago-Pima especially vulnerable to diabetes, and how can they be protected from it (Knowler et al. 1981, 1983). Other holistically inclined researchers have sought explanations for alcoholism wreaking especially great havoc among people who until recently were hunters and gatherers (Martin 1978) or for the extent to which violence and dietary behavior are integral parts of a single behavior complex (Bolton 1979, Lewellen 1981). Investigators like these and others (Lindenbaum 1979) have drawn our attention to the social factors that foster a disease or perpetuate it unnecessarily.

As a consequence of these efforts, we can view a variety of diseases—a viral disease like kuru, a lowering of immunological defenses like AIDS, and chronic biochemical upset like hypoglycemia—in a new light. We can see them not only as viral or immunological diseases but as social diseases. In the same light, we can view goiter and cretinism as a linked set of social diseases perpetuated by convenient social arrangements. These social diseases require, among other things, active social intervention. If it is to be effective, this intervention must be based on an awareness of

the various resistances within the larger national, international, and scientific contexts.

Collection of Field Data in a Longitudinal Study

The longitudinal study, which I began informally in the summers of 1965 and 1966 by establishing personal relations and mapping our focal village, got formally under way in 1972. The major part of the sixteen-month field trip begun in that year was spent in making a house-to-house census, collecting genealogies, life histories, and narratives. We spent subsequent summers and the year 1977–78 again in Asturias, returning often to the village, enriching and updating our materials. I spent summer 1984 in Spain but largely outside the village, making comparative inquiry in other villages and in other regions, interviewing physicians and other authorities on the obstacles to prophylaxis in urban centers, both in Asturias and in Madrid.

Our house-to-house census of 1972, differing only slightly from the official census of 1970, revealed 783 people distributed over 232 households. I came to be on speaking acquaintance with most of these villagers and to know some quite personally, not through formal inquiry but by participating in their lives as they intersected our lives and the lives of our children.[5] Thus, through focusing my participant-observation, I learned to identify everyone in the upper half of the village by name and to place all the villagers according to where they lived, to whom they were related, how they made a living, and how wealthy, industrious, or reputable they were in relation to others.

I hesitated to openly inquire into goiter, for I was aware that the villagers felt themselves stigmatized by it. Moreover, as already mentioned, I was profoundly aware that authorities felt obliged to deny goiter any significance. Convinced, however, that goiter was prevalent enough to warrant attention, I made a visual inspection of all the villagers and recorded my observations on the census and genealogies. On subsequent visits when updating the survey—keeping track of items like births, deaths, new construction, and resettlement—I took note of changes in the appearance of individuals, recorded goiterectomies when I heard of them or

when women showed me their scars, and added to my archive of personal histories.

The women who gave me these accounts often highlighted matters of health and disease. In this way, I informally came across a wealth of information pertaining to their own or a relative's quest for medical relief from a variety of symptoms. I learned that women received prescriptions for dietary supplements, appetite depressants and stimulants, and thyroid preparations. As these fragments of informal medical histories mounted, I began to trace the many ways in which the afflictions—reported or observed by me—were embedded in the genealogies and in the fabric of village life.

From time to time, middle-class women in the provincial capital and in three Asturian county seats also told me about their quest for relief from thyroid disorders. Hearing isolated tales of affliction narrated by urban, middle-class women, and tying these to the many tales given me by the women of Escobines, I came to discern a characteristic clinical pattern that cut across the urban-rural division. Each woman saw her thyroid problem as a discrete, isolated event; no patient and no physician (with two notable exceptions to be discussed in chap. 7) saw these thyroid cases as possibly the varied but systematic expression of one underlying problem—as symptoms not inconsistent with a diagnosis of IDD. In general, the Asturian physicians who consented to speak with me in the late 1970s refused to entertain this idea.

I concluded then that until Asturians could openly acknowledge endemic IDD in their midst, a formal investigation by a foreigner might only raise professional and political defenses in Asturias and Spain and further delay coming to terms with IDD and the initiation of iodine prophylaxis. The turning point came in 1982 when, for the first time since the days of the Republic (1931–1936), the Socialists were voted into office. On the heels of that election, regional health officials in Asturias, as well as in Galicia, a region on the western boundary of Asturias, announced (the reader may appreciate my feelings of relief and vindication) that IDD was, indeed, endemic and that they would soon be launching a provincial campaign to eradicate goiter and cretinism. National health officials followed that initiative and within a year announced a nationwide campaign to eradicate these disorders.

Direct investigation into the long-standing obstacles to pro-

phylaxis became, therefore, the principal and open focus of my field investigation in 1984, when I returned to Asturias to interview medical researchers, health officials, and clinicians. Their responses, in combination with the field material gathered in the village over previous years, serve as the raw data for my analysis.

Here I need to underscore the end to which I gathered data among two distinct field populations: Asturian villagers and Spanish medical personnel. In the village, I had to establish to my own satisfaction that IDD was endemic and how the people, individually and collectively, responded to their affliction. Once this was done, I needed to ascertain how, if at all, villagers and the conditions of village life posed obstacles to prophylaxis. Only then, after searching exhaustively for local resistance to prophylaxis, did I, a community-oriented anthropologist, search for obstacles posed by the larger social, economic, and political system and by medicine itself.

Field Methods

The materials gathered in the village are different from those out of which a formal epidemiological study is usually made, yet they have crucial value. Observations like mine can be seen as early warnings of endemic disease, enough to either prompt a formal epidemiological investigation or directly take action.

Anthropologists are specialized in two ways that bear on the method of this investigation. First, they gather materials accessible to the naked eye and the unassisted ear. Second, they relate them to genealogies, inheritance patterns, life histories, and narratives. Thus emerges a sense of the prevalence of affliction and its pervasiveness into the social and cultural fabric of a community. In my case, the affliction turned out to be IDD, but the method is broadly applicable to chronic, endemic, and nutritional disease. Tests not within the range of the anthropologist's competence may and often should, of course, provide additional and confirmatory evidence that intervention is in order.

In 1974, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined an area of endemic goiter as follows:

An area is arbitrarily defined as endemic with respect to goiter if more than 10% of its population is found to be goitrous on appropriate survey.

The figure 10% is chosen because a higher prevalence usually implicates an environmental factor, while a prevalence of several percent is common even when all known environmental factors are controlled. (Dunn and Medeiros-Neto 1974:267–268)

This definition set standards that enabled me to ascertain that the level of goitrousness in Escobines was well above the official threshold of endemicity, for the majority of women age forty and over were visibly goitrous, and these accounted for more than 10 percent of the population. In 1979, the WHO definition was adjusted, however, and from my point of view set more stringently, making me doubt that I could ever satisfy any skeptic that goiter was indeed endemic in Escobines. It proposed that endemic goiter be defined "as a prevalence of goitre of at least grade lb of 5% or more in pre- and peri-adolescent individuals or of 30% or more of grade la among adults. At this level, public health intervention seems to be called for" (DeMaeyer, Lowenstein, and Thilly 1979:9).

Visual methods made it difficult if not impossible to distinguish the grade la and lb goiters, which in normal postures are invisible and ascertainable only by palpation. Nor, with the natural attrition of the older bearers of conspicuous goiters, could I hope to demonstrate anything like 30 percent goitrousness in the general village population. By my visual method—observing people in the course of daily living and in normal postures—I could count only the higher grades of goiter: grade 2, thyroid easily visible with the head in a normal position;[6] grade 3, goiter visible at a distance; and grade 4, monstrous goiters (Ibid., 10).

Even so, I inferred from a combination of evidence that goiter was still of endemic proportions. Slightly less than half the women of Escobines age forty and over, 48 percent in this age group, appeared goitrous in 1980. This percentage did not, of course, hold across the rest of the population, for female hormones tie up iodine, making goiter vastly more common in women than in men. But the fact that fifteen women, all of them under forty, had either been goiterectomized, shown me prescribed medications for thyroid, or mentioned their exposure to the nuclear scanner (to measure the uptake of radioactive iodine) gave sufficient reason to infer that grade la and lb goiters were highly prevalent among them.

My count, by ethnographic if not by medical definition "an ap-

propriate survey," satisfied me that the prevalence of overt goiters was such as to justify searching for obstacles to prophylaxis. This private conviction, based on visual observation and confidential information, proved sound enough when the results of the official Asturian survey were finally released in 1986 (Aranda Regules et al. 1986:36, to be discussed in chap. 7.).

Indeed, the regional officials, who carried out their survey only among schoolchildren, in whom goiters are rarely visible with the head in normal position, demonstrated a level of endemicity severe enough to warrant not only the introduction of iodized salt but emergency intervention. The latter meant injecting schoolchildren in the most afflicted zones—including the zone in which Escobines is situated with iodized oil, because iodized salt had not yet become available. This emergency measure, expensive compared to the cost of iodized salt, was followed by an educational campaign and, months later, by the introduction of iodized salt. As a consequence of these measures, the biochemical indicators of IDD (T4 and UIE levels) are approaching normal. Their rise suggests that the incidence of IDD in Asturian youth will soon drop.

My study suggests that when neither clinical not biochemical evidence can be obtained to corroborate the suspicion of IDD, it is appropriate to resort to inference and standard ethnographic methods. However "indirect" the findings these measures yield, they can lend support to the initial suspicion of IDD and help to establish a demand for prophylaxis. To insist on an "appropriate survey" before prophylaxis can be undertaken may quite needlessly, as in Asturias, create an expensive emergency.

The importance of clinical and biochemical tests cannot, however, be denied. Ideally, team research including longitudinal, ethnographic, and genealogical data of the kind presented in this study should be gathered in conjunction with clinical and biochemical tests. But to insist on "appropriate surveys" as the only legitimate method of recognizing an endemia is to strengthen the supports of inaction. Legitimation of only such clinical methods gives reluctant officials the "plausible deniability" they need to continue opposing prophylaxis.

Once appropriate survey techniques, as officially defined, had established the existence of the Asturian endemia, it could no longer be denied. Only then would Spanish physicians and health

personnel help me discern the complex of obstacles to prophylaxis that had for sixty years operated at all levels: regional, national, and beyond the confines of the nation. They cooperated in helping me discern these obstacles only as those obstacles were being dissolved. This irony is worth pondering.

Argument

My central argument holds that failure to implement iodine prophylaxis cannot be explained by "underdevelopment" (Clements 1961, Dunn 1974), for it fails to explain inaction in Asturias or Spain. It must be emphasized that Asturias is a highly industrialized province with one of Spain's highest literacy rates, a province in whose most remote villages primary medical care has been available since at least the 1950s and where immunizations have been routinely offered and accepted since the beginning of this century. Something other than underdevelopment or the resistance of villagers to modern medicine—long an ethnomedical concern but in this case a red herring—must therefore account for prophylactic inaction in Asturias. Elucidation of these other obstacles is what this book is about.

Before these obstacles are addressed, however, it is necessary to discuss iodine—how it moves through the physical world and the organic system, what it does in the body, and what happens when intake is deficient. Chapter 2 offers this discussion. The arguments of subsequent chapters are based on concepts introduced in it, concepts like consanguinity, metabolic error, goitrogens, hypothyroidism, and behavioral and sensory defect.

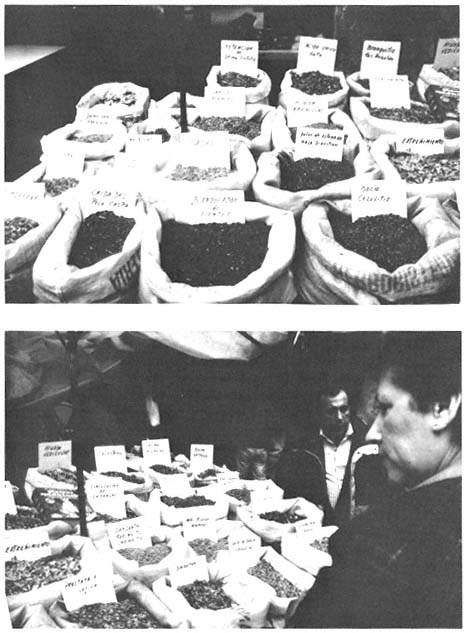

The next four chapters make up the ethnographic core of the book: the case history of IDD in an Asturian village and parish. Chapter 3, Diet and Image, shows how geology and climate produced a vegetation and—over historical time—an economy and life-style that led to dietary deficiencies. Pathologies resulting from the deficiencies, and a dialect developing out of isolation, long interacted to produce a negative image of the Asturian region, and that image itself until recently predisposed officials and physicians to inaction.

Chapter 4, Kinship and Affliction, considers the extent to which metabolic error and inbreeding played a role in producing the

disorders seen among villagers. Affliction and consanguinity are traced through the genealogies, converting them into the pedigrees of medicine. IDD in Escobines is thereby shown to be not of hereditary but of dietary causation, for the pedigree shows that only after the decline had set in did villagers cease to form consanguineous unions.

Chapter 5, Land and Diet, links poverty to the expression of IDD. As is shown here, relatively landless people resorted more frequently than others to foraging on common land for chestnuts, which are goitrogenous, and experienced IDD more severely. I argue that any complete account of IDD must take into account not only the environmental threshholds of iodine but also the dietary antagonists to which segments of the population may be subject.

Chapter 6, Narrative Accompaniments of Rural Character and Disrepute, asks why no local initiative was undertaken to obtain prophylaxis and finds the answer in part in stories and folklore. Insults, a specialized vocabulary, and denigrating stories suggest the disrepute under which the villagers have long labored, leading them to suspect themselves less capable of progressive initiatives. This chapter concludes the ethnography of affliction.

Chapter 7 moves beyond the confines of the village. Those who hold the village or region in disrepute, fault consanguinity, perpetuate diet differentials, and withhold knowledge about iodine prophylaxis are not villagers but outsiders. It is this kind of opposition to prophylaxis and the manner in which prophylactic knowledge and techniques are disseminated that come under scrutiny in this chapter. Extranational agendas, commerce, publications, and medicine played a part, however unwittingly, in institutionalizing ignorance of prophylaxis in Spain. This institutionalized ignorance is what in Spain ultimately accounts for prophylactic inaction.

Chapter 8, Closing the Gap between Therapy and Prevention, considers whether the explanation of prophylactic inaction as argued in this particular case—observed in an industrialized province of a modern Western nation—stands out as just an exception to the rule of underdevelopment. It points out how we, the outsiders, were we to take into account the contexts in which technical information is disseminated, can offset the ignorance and misinfor-

mation all too often fostered by individuals and institutions within a nation.

Because of the action initiated five years ago, the story told here is moving toward the satisfactory conclusion that might have been achieved many years ago by the simple matter of iodizing salt. Several generations of suffering might have been avoided had the kind of knowledge and awareness we seek to develop here been available and acted on in the 1920s.

Chapter Two

Iodine: An Essential Dietary Element

Introduction

The protagonist here is iodine.[1] It provides the medical background for the remainder of this work. Conventional medical presentations focus on an organ, a physiological system, or a disease, while this presentation focuses on an element. My approach relates the dynamics of iodine's movement through physical, commercial, and organic systems to the theory of trace elements, to iodine's essential role in thyroid function, and to the most common disorders engendered by iodine deficiency.

Western biomedicine recognizes the importance of iodine, but ordinary clinicians often take adequate iodine intake for granted. Spanish physicians did not normally question, or were not normally taught to ask, whether their thyroid patients' iodine intake was sufficient, though many patients came from areas previously identified as iodine deficient. Clinical symptoms were therefore interpreted as idiopathic (stemming from no known external cause) rather than as the result of malnutrition. This is an instance of a tendency widespread in the medical profession to wrongly assume a disease to be idiopathic, and treat it as such, when, in fact, it should be seen as a case of endemic malnutrition that must not only be treated but also prevented in the future.

Knowledge of iodine or of its absence as an essential dietary ele-

ment is crucial to correct diagnosis and action. I seek to give an overview of these matters here. First, I discuss the way iodine normally moves through the environment and within organisms. Following is a discussion of iodine-related pathologies.

Physical and Organic Iodine

Theory of Trace Elements

A trace element's essentiality is difficult to demonstrate, for, in contrast to bulk and macro elements that are ingested and concentrated in living tissue at levels measured in grams and kilos, trace elements are ingested and concentrated in tissue at low concentrations and are measured in milligrams and micrograms. The biological role of only a few of these elements is known at present, but the list is expanding. An early definition of essentiality held that an element is essential if it is required for the maintenance of life and if the organism dies in its absence. The definition was problematic, however, for even in a laboratory experiment it is difficult to eliminate all traces of any particular element and hence to demonstrate that death follows from total deficiency. As a result, a more workable definition of what is essential has been proposed:

An element is essential when a deficient intake consistently results in an impairment of a function from optimal to suboptimal and when supplementation with physiological levels of this element, but not of others, prevents or cures this impairment. (Mertz 1981)

A trace element is now considered essential if on ingestion in suboptimal amounts, it impairs function and on supplementation, restores it. This change in definition is significant for health policy because the presence of apparently unafflicted individuals amid a population believed to be deficient posed, according to the old definition, a problem: their very presence cast doubt on the notion that the element was essential to the maintenance of life. A well-formed, intelligent individual amid a cretinous and goitrous population seemed, in the case of iodine, to call into question the whole idea of essentiality. The new definition disposes of that obstacle to prophylaxis.

The Dose Response Curve

The dose response curve (fig. 1) illustrates the new definition. It facilitates consideration of impaired function and deals with overintake as well as deficiency. Arsenic's toxic effects in large doses are well known, for example, but its deficiency effects are only beginning to be documented. Conversely, effects of molybdenum deficiency were well known before its toxic effects were even surmised.

The shaded area on the left in figure 1 shows impaired function below a certain threshold and adequate function above it. The shaded area on the right indicates the dysfunctional aspects of over-dosage. The intake of iodine at either extreme can produce a hypoor hyperfunctional thyroid gland. Optimal function takes place within a wide range of intake, allowing for daily and seasonal variation. People can take in most of their annual iodine requirement, for example, over the course of a fishing season. The breadth of that safe margin makes it unnecessary for policymakers to spend time pinpointing "locally ideal" levels of supplementation.

A trace element does not act by itself. Its efficacy depends on organification, that is, on its becoming part of a carbon compound within a living organism. It becomes effective only on forming part of larger molecules, such as the pair of thyroid hormones, T3 and T4.

Homeostatic mechanisms buffer the ends of the range of optimal intake. Supraoptimal amounts of a trace element may simply be excreted when intake far exceeds the required level. Suboptimal intake may be buffered, as in the case of iodine, by shifting production of hormone to T3, the generally more potent of the pair, which uses fewer atoms of iodine.

Below, I describe how iodine moves through the environment, the food chain, and the body; how certain factors impede its transformation into hormone; how the body responds to marginal intake; and the disorders in which iodine deficiency plays an important though often poorly appreciated role. This understanding of the cycle, and of iodine physiology and pathology comes from standard biomedical sources (Stanbury 1969, 1978; Matovinovic 1983; Fisher 1983; Utiger 1979; Tepperman, 1980; Petersdorf 1983; Netter 1965; Pitt-Rivers 1961; Thompson and Thompson 1980).[2]

Fig. 1.

Dose Response Curve (based on Mertz 1981:1332)

My purpose in focusing on the element needs to be underscored and explained: conventional medical presentations leave clinicians and health officials without a proper appreciation for the movement of iodine through the physical and organic world, setting the stage for taking the presence and availability of iodine for granted. Prophylaxis may take a back seat to therapeutics when this movement fails to be appreciated.

The Cycle of Iodine in the Environment

Iodine makes up 0.4 percent of the earth's mass but is unevenly distributed. It is present in rock and earth in the form of soluble iodine salts that when taken up by plants, enter the food chain. Iodine's solubility makes it prone to being leached out of soil, especially in areas of heavy precipitation. In this way, it gravitates toward the sea where it becomes concentrated.

Oceanic evaporation permits iodine to become airborne and return to the land by way of atmospheric iodine transport. Climatic forces of glaciation and high precipitation leach iodine out of highlying mountain areas such as the Alps, Himalayas, and Andes, leaving many mountain populations severely iodine deficient.

Leaching is particularly severe where the parental rock is limestone, as in the Cantabrian range of central and eastern Asturias. Limestone lowlands, once glaciated, tend also to be poor in iodine. In such areas, problems of iodine deficiency are compounded, for limestone dissolves as water percolates through it, thus charging groundwater with minerals. As part of drinking water those minerals bind with iodine, making it less available for organification. The "goiter belt" of the United States, stretching from New York State to Minnesota and beyond, exemplifies such a case. As a general rule, the farther the area lies from the sea, the slower it is replenished by atmospheric transport.

Iodide is more abundant in rock and soil than in seawater, but the life forms that thrive in seawater concentrate it, for example, in kelp and fish thyroids. These substances themselves, or the ash derived from them, have long been used in China, the Andes, and Asturias as folk remedies for goiter.[3]

The largest natural storehouse and site of extraction of iodide is the Chilean nitrate bed, which was formed when ancient sea-

beds became mineralized. Until recently, most of the world's iodide production came from this deposit. With the multiplication of industrial uses of iodine in the twentieth century, iodide production has diversified, drawing on both minerals and plants for raw material. Kelp, for example, is harvested on Asturian shores and sent to other Spanish provinces for processing into gums and chemicals. Indeed, more than 99.5 percent of the world's current production of iodide and iodate is destined for industrial ends not related to nutrition. Supplementation of the world's human population with prophylactic iodine would annually take no more than 370 tons. However scarce iodine may be, even in the diets of people harvesting it from the sea for industrial purposes,[4] it cannot be considered a scarce world resource.

Dry salt mined from interior deposits may, before it is purified, be rich in iodide. But contrary to popular belief, solar salt and sea salt made from iodine-rich brine are not themselves rich in iodine, for brine contains impurities drawn off before the salt is harvested. Only artificial applications of iodide during later stages of salt manufacture ensure its iodine content.

Drinking water is frequently used as an indicator of local iodine status, though humans rarely receive more than 10 percent of their dietary iodine from drinking water. It may, however, be an appropriate indicator of intake if one recognizes that water draining the local environment generally reflects the iodine content of the vegetation, thus reflecting the iodine status of people subsisting chiefly on locally grown plant food. It is, however, a poor indicator of iodine status when the diet includes goitrogens (see below) or when the diet includes many foods of animal origin, since terrestrial iodine becomes concentrated at the top of the food chain. This means that people with greater access to milk, eggs, blood, and meat—to foods at the top of the food chain—are less likely to experience pathology than those subsisting almost exclusively on a diet of roots, nuts, and grain. A dual diet within a single zone can thus exempt the richer segment of society from symptoms while producing them in the poorer. Unfortunately, this differential effect props up belief in the innate vulnerability of the poor, while seeming to undermine the environmental hypothesis.

Iodine has been withdrawn or added to diets in unexpected ways. Disturbance of trade routes or a change in salt supply has

brought symptoms of iodine deficiency to populations formerly free of them. In Nepal, for example, newly available solar salt has supplanted the unrefined rock salt formerly transported by animal power over difficult mountain passes (Mumford pers. comm.). In New Guinea, noniodized commercial salt has suppressed traditional salt laboriously extracted from certain rare iodide-concentrating plants (Buchbinder 1977).

Commerce and industry have adventitiously introduced iodine in several ways. Subsistence agropastoralists turning to commercial feeds, for example, have inadvertently introduced iodine from outside the local ecosystem into their own food chain.[5] People have unknowingly absorbed iodine in medications and applied it as a first aid measure to the skin. The expanding food industry has introduced it into food, prompting the National Academy of Sciences to propose that "any additional increases should be viewed with concern. It is recommended that the many adventitious sources of iodine in the American food system, such as iodophores in the dairy industry, alginates, coloring dyes and dough conditioners, be replaced wherever possible by compounds containing less or no iodine" (National Academy of Sciences 1970). A more balanced statement by the academy would have addressed not only national surfeits but also global deficiencies, taking into account as well the dangers at the low end of the dose response curve. The academy thus displayed the unexamined assumption of "iodine affluence" characteristic of much of Western biomedicine. Health workers in the Midwest have recently reported the reappearance of goiter on farms (NYT Sept. 29, 1987:1), calling into question the assumption of iodine affluence even in the United States. In chapter 7, we will see how this assumption has been exported around the globe.

The Physiology of Iodine

Basic Understandings

Marine demonstrated in 1915 the essential role of iodine in thyroid physiology. His findings led to pilot iodization projects in both Switzerland and the United States. Favorable evaluations led to mass prophylactic programs carried out by governmental authorities in Switzerland and essentially by commercial entities in the

United States (Matovinovic 1983). Mass prophylaxis was not, however, extended to most other populations also known to be endemic, such as people residing in the Alps of Austria, Germany, and France or in parts of Scandinavia and Spain. Why this should be so is of course the problem of this book. To begin to answer that question, one must know the basic scientific premises on which the prophylactic programs of the 1920s were launched.

Iodine compounds once ingested are broken down and pass into the blood as inorganic iodine (see fig. 2). The thyroid then captures the circulating iodine, joins it onto proteins, and transforms it into the hormone thyroxine, which is stored in the thyroid and released into the blood stream as needed. Thyroxine is essential for optimum growth and for the metabolic processes taking place in tissue. After the hormone has been used, it is broken down and its iodine component recirculated, part of it passing out of the system by way of the kidneys. Iodine lost through this route is known as urinary iodine excretion (UIE),[6] a rate that measures the iodine status of a population. By WHO standards, a population is iodine deficient when its average UIE falls below 50 micrograms (µ) per day. Mass iodine supplementation averaging 150 micrograms per day gradually raises a population's UIE to normal.

Goiter is an enlargement of the thyroid gland, variably manifest as a bulging growth situated at the front of the neck, a diffuse thickening, or an enlargement behind the sternum. The enlargement permits the gland to trap a higher proportion of circulating iodine. Supplementation diminishes the need for trapping and permits glands not too long established to recede to normal size.

In the early days of prophylaxis in Europe, a set of "anthropological" traits were also taken, apart from goiter, as indicators of iodine deficiency. Corporeally, these indicators were short stature, dwarfism, structural peculiarities of the shoulder, hip and foot defects, and a peculiar walk. Facially, they were a broad nose bridge, droopy eyes, and lack of expression. Prevalence of these signs in combination with a conspicuous number of deaf-mutes was taken as a sign of severe iodine deficiency. Severely impaired individuals were known as cretins.[7] Their pathology was seen as separate from but related to endemic goiter, for scientists and laymen had long observed that endemic cretinism was rarely found where goiter was not also endemic.

Fig. 2.

The Thyroid and Its Feedback System

Public health officials in Switzerland, where cretinism was endemic, therefore targeted the iodine supplement at both conditions, while in the United States, where cretinism was not endemic,[8] goiter alone was targeted for eradication. That difference in targets becomes significant in elucidating the obstacles to prophylaxis, for iodine prophylaxis in the United States came to be

associated exclusively with the prevention of goitrous deformities, not with the prevention of motor and sensory disabilities.

As a result of these differing approaches, the essentiality of iodine came to be widely appreciated: in Switzerland, through official public health channels and in the United States, through commercial advertisements for salt. However vaguely, people consuming iodized salt accepted the theory of iodine deficiency.

Except for the Swiss, however, few Europeans were exposed to the theory of iodine deficiency. Endemic goiter nevertheless gradually declined in most of the Western world as food supplies became increasingly delocalized and as iodine entered increasingly into the diet. In other words, neither supplementation nor public education played a significant role for most Europeans in the decline of endemic goiter and cretinism.

Medical publications reflected this decline: once the overt threat of endemic goiter had receded, so did articles focusing on the once-threatening disease. However vividly the theory of iodine deficiency had once been presented on both sides of the Atlantic,[9] the public and its physicians before long came to take iodine sufficiency for granted.

Current Understandings

Basic knowledge on which prophylaxis was established has, over the intervening sixty years, been elaborated into a refined theory and practice that is a powerful agent in managing thyroid disorders (see, e.g., Stanbury 1978). But these advances concern us here in only a limited way: (1) insofar as they promote dietary intervention or cast doubt on it, and (2) insofar as they prepare us to understand the villagers' symptoms and the treatments to which, as we will see in the ethnography, they have been exposed. Four examples will illustrate these advances.

First, concern about the loss of homeostasis has restrained many physicians from endorsing prophylaxis. These physicians were convinced that the sudden introduction of physiological amounts of iodine into individuals long adjusted to a scarcity of iodine might trigger hyperthyroidism (Plummer 1936). This conviction was propounded with much flair during the prophylactic era, so that persistent fears about sudden iodization lingered even after the

idea was disproved. In Europe, the feared phenomenon came to be known as "Basedowification"—hyperthyroidism renamed for Basedow, a nineteenth-century physician who was a militant opponent of iodine supplementation. In his day, supplements were administered on an empirical basis, in doses now known to have been of pharmacological, rather than physiological, magnitudes. Such doses did perhaps prompt pathology. Fear of Basedowification is now uncalled for, however, because, among other reasons, dietary iodine supplement is available only in physiological doses. Yet at least one diagnostic manual recently republished in Spain still cautions physicians about abusive self-dosification (Marañón y Balcells 1984).

Second, the discovery of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) strengthened the view that goiter is an anatomical/physiological adaptation that need not be prevented. The adaptationist view holds that TSH, rising in response to low levels of circulating thyroxine, prompts the proliferation of thyroid cells, implying thereby neither dysfunction nor uncontrolled cellular proliferation. TSH does stimulate the thyroid into work hypertrophy and does enable it to trap a higher proportion of circulating iodide; in this sense, it is indeed adaptive. The view fails to take into account, however, that under conditions of optimal iodine intake, rising TSH warns of dysfunction. The adaptationist view also fails to take into account the higher risk of thyroid cancer.

Third, the uneven distribution of goiter, which tends to affect females more than males, has come to be understood in the following way. Estrogens increase during adolescence, rise during pregnancy, fluctuate during menopause, and are exogenously introduced by way of birth control pills. Estrogens increase the binding of iodine, making it less available for organification. Thus, periods of elevated estrogen production in the female life cycle increase the need for iodine and thyroid hormone. Increased levels of TSH reflect this need and may, during these phases of a woman's life cycle, drive the gland into hypertrophy so as to meet the increased demand. This sex difference—where the severity of endemic iodine deficiency is such that the necks of most males appear normal—allows goiter to be seen as a woman's problem rather than a problem of malnutrition that, however variably,[10] affects both

sexes. Observed solely as a woman's problem, goiter seemed to call for therapeutics rather than for massive dietary intervention to correct the underlying environmental deficiency.

Fourth, thyroxine was in 1953 differentiated into two hormones, T3 and T4, differing in potency and in the number of iodine atoms in the molecule (MIT and DIT).[11] Knowledge of the two hormones seemed for a time to make dietary intervention less urgent, for it was observed that under conditions of iodine deficiency, the T3/T4 ratio shifted in favor of T3, the more potent hormone. Animal experiments later disclosed that while T3 does rise compensatorily in most of the body, it does not rise in the brain tissue, where T4, under conditions of suboptimal dietary intake, is already low. In rats, this constellation of hormone levels was accompanied by suboptimal brain function (Greene 1973, Escobar del Rey et al. 1981b ), which improved measurably after supplementation. These animal experiments led researchers to infer that the brain function of clinically symptomless children might also be improved by supplementation.

Indeed, supplementation has been found to increase the level of circulating thyroid hormones in children whose hormone levels were within the so-called normal range (Connolly, Pharoah, and Hetzel 1979). The rise occurred only in subclinical cases, in children free of symptoms who had, however, low levels of hormone. The rise did not occur in children whose hormone levels were normal and whose iodine intake was optimal. These findings suggest that the apathy and low cerebral function attributable to suboptimal hormone levels tend to escape the clinician's notice. Both measures can be improved, however, as was shown when the children's biochemical levels and school performance both rose on supplementation. One can therefore conclude that the hormonal shift preserves corporeal but not cerebral homeostasis. In other words, it protects the body more than the brain (Lancet 1979:1165–1166, 1983:1121–1122), making dietary intervention more urgent. Denying iodine supplements to a population because it is not blatantly goitrous may then be seen as a means of keeping it apathetic and docile. In other words, goitrouslessness should be no reason to withhold iodine prophylaxis, for subclinical thyroxine levels reduce vigor and intelligence (Delong, Robbins, Condliffe 1989).

Other Factors: Goitrogens and Metabolic Error

Western medicine, during the prophylactic era, understood iodine deficiency as the major cause of endemic goiter and cretinism. Since that era it has given increasing prominence to the role of goitrogens and metabolic error.

Goitrogens are any active forces or substances that induce goiter. They act in at least three ways, by affecting (1) the absorption of iodine into the bloodstream, (2) the chemical coupling of MITs and DITs to tyrosene, and (3) the binding of molecules. Goitrogens play an insignificant role in goiter and cretinism where the diet is varied, but where it is not (as in rural Asturias), they can play an extremely important role. In this chapter, I discuss only the goitrogenic mechanisms. In chapter 5, I will show how poverty induces a high goitrogen intake and how a selectively goitrogenous diet, for the physiological reasons given here, helps to keep segments of the population socially marginated.

Absorption is affected by thiocyanate, a substance produced either in the liver or intestine during the course of digesting foods from three plant families.[12] Cassava is of the Euphorbiaceae (formerly Manihot) family, a starchy root widely consumed in the developing world. Cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, rape seed, kale, collards, and turnips are of the Brassica family, and radish, cress, and mustard are members of the related Crucifera. Foods from these botanical groups are widely consumed in Europe and the temperate parts of the world, sometimes as garnishes and often as daily fare.

Thiocyanate produced by these goitrogenous foods preempts the sites on fatty acids to which iodine ordinarily binds for its passage through the intestinal membranes. Thiocyanate thus impedes the passage of iodine into the circulation and promotes its loss through feces. This loss is insignificant where iodine is abundant, but where it is scarce, thiocyanate slows down hormone production.

Perchlorate is another goitrogen acting in the same preemptive way in the intestine. While abundant in a variety of nuts, perchlorates are especially abundant in chestnuts (L. castanea sativa ), beechnuts, and acorns.[13] In historical Europe, these nuts were considered "hungry foods," consumed as staples of daily fare only dur-

ing war or when grain crops failed. But as will be seen in chapters 5 and 7, they were regularly consumed where grain was habitually scarce.

Goitrins, another form of goitrogen, interfere with the coupling of MIT and DIT molecules. They too may be derived from cruciferous plants, more from turnips than from cabbage, becoming goitrins only in the presence of certain intestinal parasites that arise locally. They may also, as in one well-known case, be derived from volatile compounds of geologic origin. Where because of the prohibitive cost of fuel, only the richer segment of the population boiled its water, driving off these volatile compounds, only the poor became goitrous (Gait'án 1974). Goitrins like these pique the curiosity but play an insignificant role in the global distribution of endemic goiter and cretinism and contribute little to understanding the obstacles to prophylaxis.

Finally, there are mineral goitrogens that, absorbed through drinking water and passed into the bloodstream, act to bind iodine, thus making it less available for organification. The best-known mineral goitrogens are produced in groundwater flowing over bedrock of limestone, where minerals such as calcium and fluorine dissolve out of the rock, enter the water supply, and are ingested with drinking water. Mineral goitrogens like these are characteristic of the central Asturias and of the historical goiter belt of the American Midwest.

Hereditary metabolic error has come to assume, since midcentury, an increasing role in thyroidology and has become an important consideration in the diagnosis and management of goiter. Metabolic errors may impede iodine metabolism at several sites: they may impede the transport of iodine, the coupling and breakdown of molecules, and the recapture of iodine, leading in these several ways to symptoms like those produced by suboptimal iodine intake. While metabolic errors must be seriously considered in any idiopathic case of goiter or of other thyroid-related diseases, they have rarely been shown to play an important role in goiter and cretinism that is endemic. Even where the stage has been set for the concentration of metabolic error in inbred populations, iodine supplements have dramatically reduced the incidence of IDD. However, since popular interest in inbreeding outweighs popular interest in prevention, it serves the interest of the opponents of

prophylaxis to stir up renewed interest in inbreeding, thus distracting attention from prevention.

Supplementation