The Spatial Reorganization of Exchange

After its economic transformation as before, Buguias depended on trade for its livelihood. But whereas the community had once formed the hub of an essentially local circuit, it was now reduced to an outlying production zone for the national market. For centuries, Buguias had been tenuously linked to the international economy through the Suyoc gold trade; now it was directly dependent on global resource flows.

As the position of Buguias and neighboring communities shifted vis-à-vis larger economic structures, the spatial patterns of the local economy reformed. This process manifested itself, in part, in the emergence of distinct agricultural regions, one of which was coterminous with the territory of Buguias Village. But for local exchange, it was the road network, connecting the vegetable districts with the Baguio and Manila markets, that emerged as the organizing framework.

The Displacement of Buguias Central

The immediate postwar years saw the rapid rise of Buguias Junction (Kilometer 73 of the Mountain Trail) as the new trade center of the greater Buguias region. Before the Agno Valley Road reached Buguias in 1958, all local vegetables had to be ported to this site. A number of Buguias residents soon moved to Kilometer 73, both to farm and to take advantage of the emerging market. As commerce began to settle in place, the tradition of peripatetic trade withered.

On market days (Thursday and Sundays), those Buguias farmers with produce to sell would begin their strenuous hikes to the Mountain Trail hours before dawn, lighting their way with pine torches. The habitués of the market at Kilometer 73 included many others as well; since few Buguias traders now ventured into the cloud forest, its residents also began to trek to this emergent entrepôt.

As its marketplace grew, Buguias Junction displaced Buguias Village as the center of the regional meat trade. The Agno Valley no longer produced many animals, nor did its traders procure meat in the eastern oak woodlands. But demand persisted, even strengthening in times of high vegetable prices. The few Buguias residents who had purchased trucks for vegetable hauling now began to import animals directly from the lowlands. But within a few years, Ilocano entrepreneurs discovered this profitable trade, and before long lowlanders all but monopolized the transport of livestock.

The Rise of the North

Buguias Junction's ascendancy proved short-lived; by the 1960s exchange had jumped to other centers. Buguias itself reclaimed a minor commercial role as it gained road access and as the cloud-

forest people began to hike to the village for their needs. But this did not last long either, since Buguias was soon far overshadowed by two new mercantile villages in the northern part of the municipality: Abatan and Bad-ayan.

Abatan, situated on the junction of the Mountain Trail, the Agno Valley Road, and the Mankayan-Cervantes Highway, had long been a natural market site. A few permanent businesses clustered around the crossroads in the prewar period, to be joined by several more following the armistice. But Abatan developed slowly. Some attribute its retarded growth to the arrogance of certain Lo-o baknangs who had established the first stores. These early merchants would reportedly intimidate any potential competitors, in some instances simply expelling them from town. Not until Northern Kankana-ey and Ilocano merchants arrived—people not so easily bullied—did Abatan flourish. The northern traders first dickered in a new periodic market, but gradually a number of them constructed permanent stores. By the early 1970s, Abatan reigned as the premier trade depot of northern Benguet and as the new de facto seat of the Buguias municipal government.

Lo-o, only a few kilometers east of Abatan, did not suffer as the latter town rose. Rather, the two communities were close enough to form something of a single trade hub, and a number of small businesses also emerged in central Lo-o. Lo-o also benefitted from its thriving agricultural high school and from the Buguias Town Fiesta, celebrated annually on the school grounds.

Bad-ayan, while never rivaling Abatan, gradually emerged as the second trade center of the Buguias region. Exchange gravitated here during the early 1950s, when Bad-ayan marked the terminus of the Agno Valley Road, and it expanded when a periodic market was established in 1957. Permanent stores were soon built by Badayan residents, and two of them evolved into fully stocked agricultural supply houses. By the 1960s, road extensions to the east gave the village a growing hinterland of its own. Now Bad-ayan was the most accessible town to the cloud forest of western Ifugao province.

Gradually a stable periodic market system developed, linking the various old and new commercial centers of northern Benguet. David Ruppert (1979) discovered in the 1970s that just over half of the market vendors in Abatan were Igorots (mainly Northern Kankana-ey), the others being largely Ilocanos and Pangasinanes. Virtually all were women. By the mid-1980s, many vendors rotated

Map 7.

The Changing Spatial Structure of Buguias Trade.

from Lo-o on Wednesdays, to Bad-ayan on Thursdays, to Abatan on Fridays and Saturdays, and finally to Mankayan on Sundays before journeying to Baguio or even Manila to purchase new supplies.

The Market in Buguias Central

When the Agno Valley Road was finally pushed south to Buguias, local trade temporarily revived. Thursdays and Sundays were des-

ignated market and produce-shipping days; vegetable traders would then drive their large trucks to the center of town, where they would be greeted by growers descending from the surrounding farmlands with their harvests. After selling their vegetables, farmers would shop in the periodic market and in the half-dozen or so permanent stores that had recently opened. But the shops of Buguias offered fewer goods at higher prices than their rivals in the northern towns, and the market was a local affair, unable to attract the professional peripatetic vendors.

When marketing innovations in the 1970s permitted farmers to ship their vegetables on any day of the week, the Buguias market withered to virtual extinction. Most farmers continued to devote Sundays and sometimes Thursdays to socializing in the center of town, but by the mid-1980s only a single used-clothing trader offered any substantial goods in the marketplace.

Connections with the Global Economy

The Benguet vegetable farmers became entangled in the world economy not primarily as producers for a global market, but rather as consumers of agricultural supplies produced in the metropolitan states. Certainly international economic ties are implicated in vegetables sales—the tourist hotels of Manila and the American military bases are large and steady produce customers—but little is exported. By contrast, most of the industry's inputs are imported. Russell (1983) has argued persuasively that the companies supplying these goods extract a substantial surplus from the vegetable growers.

The transport systems of economically subservient regions often assume a dendritic pattern, in which roads effectively channel resources from the interior to an export entrepôt without developing corresponding internal connections (see C. Smith 1976). Benguet is no exception. Here too a dendritic pattern is readily discerned in the still-developing road network. Internal transport remains tortuous, for almost all trunk and feeder routes culminate in Baguio, from which point a busy highway leads directly to Manila.

The agricultural inputs employed by the Benguet farmers fit into three major categories: fertilizers, biocides, and seeds. Each developed its own pattern of supply and distribution, in which one can trace the global geographic patterns underlying the vegetable in-

dustry. As of the later 1980s, Benguet is linked to all of the world's centers of economic strength, including several emergent ones.

Approximately 40 percent of the typical farmer's fertilizer budget goes to chicken manure. This input is domestic, produced on poultry farms in central Luzon. Tagalog merchants truck manure into the mountains, often delivering it (sometimes on their backs) to very remote locales. Chemical fertilizers are of two major kinds: ammonium sulfate, providing nitrogen, and so-called complete, a balanced plant food. Although the Philippine government has made efforts to foster a domestic fertilizer industry, most supplies are imported. At present, the largest suppliers, especially of ammonium sulfate, are Taiwan and South Korea.

Biocides (including insecticides, fungicides, and herbicides) are largely manufactured offshore by multinational corporations. As of 1986, four companies predominated, two German (Hoescht and Bayer), one Anglo-Dutch (Shell), and one American (Union Carbide). While their products are sold by local distributors, these companies maintain a strong presence in the vegetable industry, particularly through their advertisements and other competitive activities.

In the early days of vegetable growing, American companies supplied most seeds. Gradually they have been supplanted by Japanese competitors; today only lettuce seeds are routinely imported from the United States. Seed potatoes have been generally procured from western Europe, but local supplies (developed largely by a Philippine-German cooperative project on the slopes of Mount Data) are becoming increasingly available. Quality seed procurement has long been a bane of the Benguet farmer. The demand for seeds of early maturing cultivars especially is often unsatisfied (FAO 1984). Moreover, several Buguias farmers complain that they cannot grow several potentially profitable crops, such as scalloped squash, because they are simply unable to obtain seeds.

The multinational agrochemical companies dispense much selfserving information to Benguet farmers through their field agents. Indeed, these agents, rather than government extension personnel, are the main source of new technical information (Medina n.d.:2). Many, if not most, company operatives are local residents, usually graduates of the agricultural college in Trinidad. These agents organize meetings for growers when they have a new chemi-

cal to sell, selecting "demonstration farmers" who receive the product free in exchange for cultivating "test plots." The typical recipient is a successful farmer who possesses an easily visible roadside garden. Other farmers then inspect the experiment to judge whether the new input is worthwhile.

Such advertisements often prove successful for the sponsor. Farmers use substantial quantities of chemicals, although applications have decreased somewhat since the crisis of the early 1970s. Previously, many growers used biocides prophylactically and to great excess (Medina n.d.:2). But despite the recent decline, the spraying of biocides is incessant, and the environmental and medical consequences appalling.

In short, the postwar transformation both reordered Buguias's agrarian ecology and repositioned the community within the global economy. In so doing, it undermined the old bases of social hierarchy: pastoralism and Cordilleran trade. But at the same time, the new order presented abundant opportunities for the elite—both old and new—to (re)assert dominance. Here one may find both striking discontinuities between the prewar and the postwar eras and profound carryovers as well.

1. Headman of Buguias, 1901. Courtesy, Worcester Collection, University of Michigan. Themeda pasture

is visible in the background, with scattered young pines in the higher areas. On the far left, several

fence lines may be distinguished.

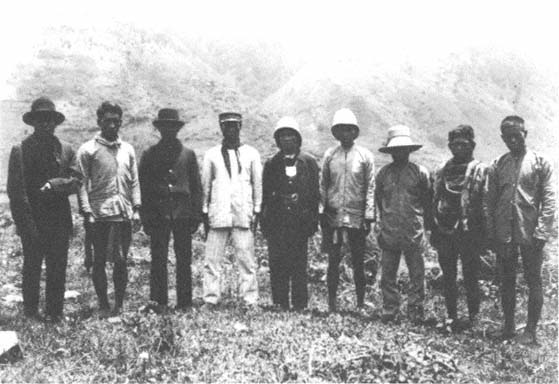

2. A Group of Buguias Men, Circa 1900. Courtesy, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago.

Intensively cultivated uma fields, stone walls, and small houselot gardens are visible in the background.

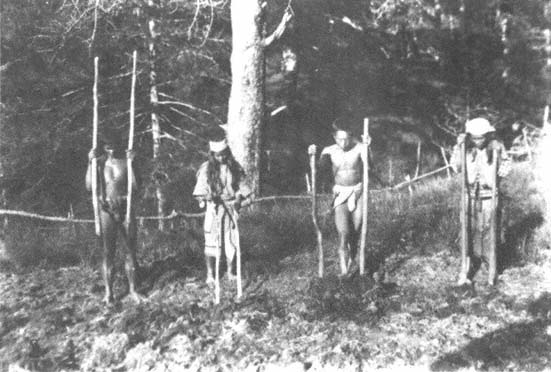

3. Puwal Cultivation, Circa 1900. (Originally titled "Igorots breaking ground with pointed

sticks, Baguio, Benguet.") Courtesy, Worcester Collection, University of Michigan.

4. Southern Cordilleran Traders, Circa 1900. (Originally titled "Igorot carriers on the trail.")

Courtesy, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago. These merchants have likely just returned from the

lowlands, where they would have purchased the dogs. In Buguias, women seldom joined such expeditions.

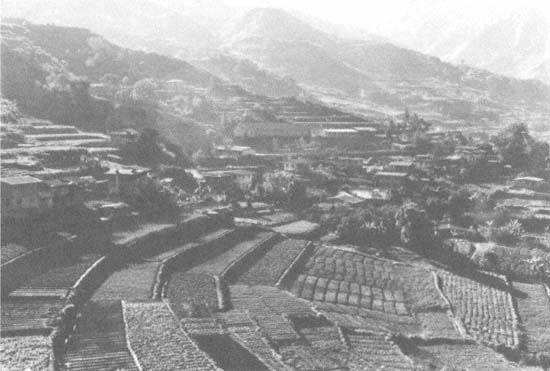

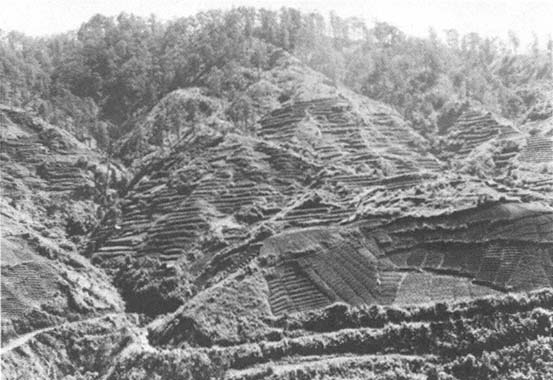

5. Buguias Village in 1986. Only the central part of the community is visible.

6. Sloped Fields and Pine Forests near Buguias, 1986. This area, just south of the village, has experienced

rapid field expansion and forest retraction in recent years. Note the roadway in the foreground.

7. Carrot Harvest, Buguias 1986.

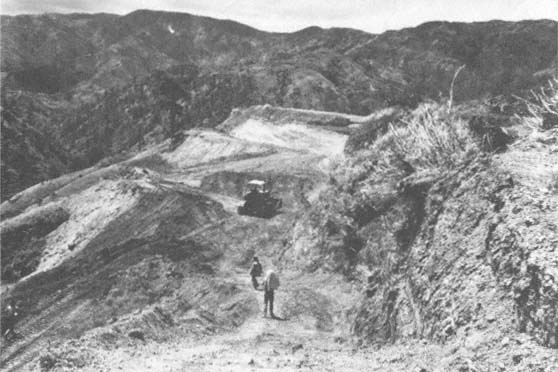

8. Bulldozing "Mega-Terraces," East of Buguias, 1986. The bulldozer cuts deeply into the subsoil,

a nutrient-poor but friable material that will make an adequate cropping medium once fertilizers are applied.

9. Manbunung (Pagan Priest) and Sacrificial Hog, Buguias 1985.

The blood-soaked taro slices on the animal's back symbolize cash.

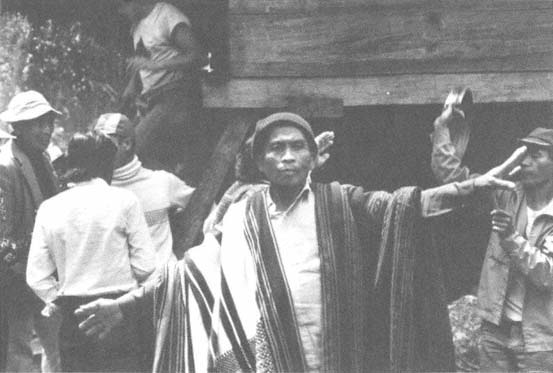

10. Ritual Dancing in Buguias, 1985.

Wearing a death shroud, the dancer is performing in the stead of one of his ancestors.