5

The Terrible Years

Depuis 89, il y a toujours eu un roi de France, et il n'y en a eu qu'un seul: c'est Paris.

Louis Veuillot, Paris pendant les deux sièges

Since 89, France has always had a king and only one: Paris

On 4 September 1870, the newly constituted Government of National Defense proclaimed France's Third Republic. It was a date that echoed back across the century both to the fall of one earlier regime and to the beginning of another. Whatever hopes the proclamation contained, the blue, white, and red tricolor waved in bitter victory. The most fervent Republican could take little joy in a triumph born of dishonor and defeat. On 2 September, after the disastrous rout by the Prussian troops at Sedan and barely six weeks after the French declaration of war, Napoléon III capitulated to the Prussians at Sedan. The humiliation was all the greater and the irony all the crueler because this war, which sent the French empire down to defeat, witnessed the (re)birth of an arch rival. On 18 January 1871, Bismarck and William II announced the establishment of the German empire from the same Hall of Mirrors at Versailles in which the new republican government was negotiating the official capitulation of France.

Yet the Treaty of Versailles that ended the five-month siege of Paris and imposed such harsh terms on the country—notably, the payment of significant indemnities, the surrender of Alsace-Lorraine, and the occupation of Paris by the German army—played out only the second act of the tragedy that Victor Hugo called "The Terrible Year." The Third Republic received its true baptism in the desperate civil war that followed Sedan in the fighting of French against French. The Terrible Year saw France oppose and then conquer Paris. On 28 March 1871, four weeks after Prussian troops finally entered the city after a siege of several months, its duly elected members proclaimed the Commune of Paris, signaling its rejection of the armistice that had been negotiated by the fledgling republican government. Two

months later the final battle for the city of Paris pitted the woefully outnumbered Communards against veteran troops dispatched by the new government at Versailles. At the end of the "Bloody Week," significant portions of Paris lay smoldering in ruins, and more than twenty thousand Parisians lay dead, the immense majority not killed in actual combat but summarily executed under orders by the French army. To gauge the dimensions of the slaughter, we need only note that the army lost just 877 men.[1]

The long shadow cast by the Commune over the Third Republic looked all the darker by virtue of insistent, inescapable parallels with 1793. That, too, was a Terrible Year. Then, too, foreign armies threatened the integrity of the country; civil war tore the country apart; and a republican government exterminated its enemies in the name of justice. Just as much separated the First and the Third Republics. Instead of the glorious French victories that repulsed the coalition of Prussians, Austrians, British, and Russians in the 1790s, the war of 1870-71 brought ignominious submission and occupation by Prussian troops. In 1793 Paris and the new revolutionary government held the key to victory and to the new society while a counterrevolutionary alliance of peasants and royalists worked from a territorial base in the far reaches of western France. In 1871, Parisians were the rebels to be crushed. Even before the declaration of the Commune, the republican government had "decapitalized" Paris by electing Versailles as its headquarters. In 1789 ordinary Parisians marched to Versailles demanding that the king come to the city; 1871 saw the invasion of the city by republican troops sent from Versailles. In 1793 the republic executed the king and ratified the new sovereign. "Since 1789," as the monarchist critic Louis Veuillot so aptly observed, "France has always had a king and only one: Paris."[2] In a twist of irony that can have escaped none, in 1871 the army from Versailles executed Paris and decapitated France.

The Third was manifestly not the First Republic. The very limits of the monarchical analogy point to the great disparity between the two. Modern Paris could not so easily be vanquished. Paris—the capital of the nineteenth century—spoke to the future, not the past. This monarch could not so easily be executed. Yet the blow dealt to the city created an untenable situation. If the defeat of France devastated the country, the defeat of Paris called into question the legitimacy of the government. The opposition of Paris and the provinces was not

new, but the Terrible Year gave it new vitality and jeopardized the claims to progress made for Paris since the beginning of the century.[3] This dilemma required an entire cultural reconfiguration of the city.

If the city could not be overthrown, it could be, and had to be, redefined .Just as the execution of Louis XVI in January 1793 required the reconceptualization of the royal topography, so the "decapitation" of Paris in 1871 severely compromised the understanding of the modern city and especially its claims to world leadership. Where was Balzac's queen of cities, monstrous marvel, and courtesan? An even more devastating sign of loss, where was Hugo's luminous city, the "head" of France and even, in Hugo's grandiose conception, the leader of the whole world? Events forced Hugo to think the unthinkable and to pose the awful question: "Can the human species be decapitated?"[4] By way of answer to that question, the Third Republic diligently rewrote Paris. It compelled a new city, new urban practices, and these in turn demanded a new urban poetics. Once again, new texts were in order to enable the city to be read in a new way.

Victor Hugo and Jules Vallès supplied some of the most striking of these new texts. In very different modes, each writer offered a model of and for the changed city. Each spoke for, and to, a Paris that could recover from the shame of defeat and regain its sovereignty. Each author undertook to rewrite revolutionary Paris for what turned out to be a postrevolutionary age. That neither succeeded in imposing his vision on French culture is telling. Ultimately, their failures testify to the ideological impasse of the Revolution as the nineteenth century drew to a close. The catastrophe of 1871 and, even more, the politics of the Third Republic drastically undermined the revolutionary vocation of Paris. Despite Hugo, despite Vallès, revolution no longer served as an interpretive model for urban space.

I

Je vis dans l'exil; là je perds le caractère de l'homme pour prendre celui de l'apôtre et du prêtre.

Victor Hugo, Journal d'Adèle Hugo

I live in exile; there I am losing the character of a man to take on that of the apostle and the priest.

No writer, before or after 1871, was more forcefully identified with Paris than Victor Hugo, and few celebrated the city as passionately or

as constantly as he. From Quasimodo's defense of the cathedral and the celebrated bird's-eye view of medieval Paris in Notre-Dame de Paris of 1831 to Jean Valjean's dramatic escape through the sewers in Les Misérables of 1862, from the 1827 "Ode à la Colonne Vendôme" of the young liberal royalist to the introduction to Paris-Guide of 1867 by the fervent quasi-socialist republican and to the poems in L'Année terrible, Hugo obsessively returned to Paris again and again.[5] The city was at once his subject and his object. One caricature of 1841 shows him dominating the cityscape, astride the Seine, a pile of (his own) books at his side. In the background appear all the places Hugo had either written about or been associated with in the city, from the cathedral of Notre-Dame to the theaters where his plays had resounding success to the Académie française to which he had recently been elected.

Paris, Hugo never tired of repeating in one colossal form or another, guided the universe. It was, as he proclaimed in the introduction to Paris-Guide, the "focal point of civilization" (XIX) and its history was a "microcosm of general history" (VI). Moreover, Paris owed this centrality to the Revolution. He wrote, "1789. For close to a century, this number has preoccupied the human race. It contains the whole of phenomenon of modernity" (XVIII). Naturally, Hugo took this revolutionary modernity as his own and, sometimes, as himself! The often cited definition of romanticism from the preface to Hernani (1830)—"romanticism, all things considered, . . . is only liberalism in literature"—emphatically proclaimed the connection between the literary and the political that would define the writer's career over the next half century, his politics no less than his literary production. Hugo's pact with Paris was a true covenant, both the product and the sign of his belief in the pivotal role played by the Revolution of 1789 for all of human history.

These associations with the Revolution were clear well before Hugo went into exile in December 1851, immediately after the coup d'état of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte reversed the Second Republic and led, a year later, to the proclamation of the Second Empire. Revolution pervades Hugo's work. Take, for example, Notre-Dame de Paris. Notwithstanding the subtitle of 1482, this is manifestly a novel of 1830. Beyond the chronicle of 1482, beyond the melodrama of love and lust that opposes Quasimodo the hunchback, Claude Frollo the priest, and Esmeralda the gypsy, beyond the recreation of the late medieval

city, Notre-Dame de Paris inscribes the present. Of course, this work has all the trappings of the historical novels made so popular in the 1820s by the many translations of Scott. Although Hugo undertook serious historical preparation for the work, he does not write historical novels. That is, he does not construct a past that exists on anything resembling its own terms. Nor does he claim to do so. Quite to the contrary, and throughout the novel,l he insists upon the living present. "We, men of 1830" is a constant refrain, and Hugo continually opposes fragmented modern Paris with its motley architecture and the organic Paris of the late Middle Ages, which finds its highest expression in the cathedral of Notre-Dame.

Of course, 1830 is not just any year. It is the year of the July Revolution, which erupted just as Hugo began to write Notre-Dame de Paris. The very first lines of the novel situate the writer very specifically in the revolutionary present: "Three hundred forty-eight years six months and nineteen days ago today. . . . "A count forward from the date given later in the paragraph leads the reader to 25 July 1830, that is, two days before the July Revolution broke out. Yet Notre-Dame de Paris represents neither the present, 1830, nor the past, 1482, so much as it reconfigures 1789. As Hugo reaches back to the waning Middle Ages, he looks forward to the Revolution of 1789. The unsuccessful revolt of 1482 represented in the novel, like the successful revolution of 1830 alluded to in the text, makes sense only in reference to 1789, which is the realization of the one and the origin of the other. These explicit references, like Hugo's editorializing more generally, are only superficial symptoms of a more constitutive rationale. The Revolution of 1789 dominates the entire novel, its images, its metaphors. The Bastille looms so large in the novel because its future destruction will commence the Revolution. If Louis XI successfully puts down the Parisians' revolt in 1482, readers of 1830 are never allowed to forget that some three hundred years later, Louis XVI will not be so lucky. Typically the confidence of Hugo's king in the capacity of "my good Bastille" to withstand an uprising forces the revolutionary intertext upon the most obtuse reader.

In keeping with Notre-Dame de Paris and the many dramas written in the late Restoration and the early July Monarchy, Hugo's exile during the whole of the Second Empire put into practice the revolutionary identification that he had long preached. "Romanticism and democracy are the same thing," he declared in 1854, carrying

Plate 14.

Frontispiece by D. Vierge to Victor Hugo, L'Année terrible

(1874). The first illustrated edition of Hugo's collection of

poems on 1870-71. The year is encapsulated by the German siege at

top and the burning of Paris at bottom. (Photograph courtesy of

the Library of Congress.)

his earlier definition of romanticism one step further.[6] No public figure defied the Empire of Napoléon III with greater vehemence or greater personal drama. For eighteen and a half years, from Brussels, from the Channel islands of Jersey and later Guernsey, his diatribes against the man whom he baptized "Napoléon the Little" made him the most visible of those who fled or opposed the Second Empire. Hugo's scorn for the amnesty offered by the emperor in 1859 magnified the original act of exile a hundredfold. In ostracizing "ideas, reason, progress, light," Napoléon III sent "France itself" into exile. "The day that all that comes back," Hugo notes in his diary (19 August 1859), then and only then will he return. From that moment and that decision onward, Hugo's exile was entirely a matter of principle. Although he gave up writing for the theater after the failure of Les Burgraves in 1843, Hugo never gave up drama. He staged and performed his exile. Arguably, it was his best drama—certainly the one with the longest run and with the greatest effect.[7]

The theatrical gestures in which Hugo excelled did not simply publicize an existing or precisely formulated political position. They belonged inherently to a politics of performance. Performance formulated the position. Hugo was, arguably, France's first modern media hero for whom the medium was the message. A famous, widely diffused photograph shows the writer on a rocky promontory above the sea sternly facing France. In 1854, after only three years in exile, he already saw himself "losing the character of a man to take on that of the apostle and the priest."[8]

Hugo's return to France, on 5 September 1870, the day after the proclamation of the republic, resurrects the man in the apostle and the priest. The whole event is a good measure of the successful (re) constitution and manifestation of self as a political symbol. When Hugo's train passed through the Normandy countryside, people lined the train tracks to cheer the returning hero. So dense was the crowd waiting at the Gare du Nord that his party took over two hours to traverse Paris to where he was staying near the Étoile. As Hugo recounts the day in his journal, he had to speak four times. This tumultuous welcome in turn merged into the Hugo legend, thanks to the wide diffusion through newspaper reproductions. In this moment Hugo was Paris. So intense, so passionate, was the conjunction of the writer and the city that it seems perfectly natural that the Société des Gens de Lettres should request Hugo's authorization for a public

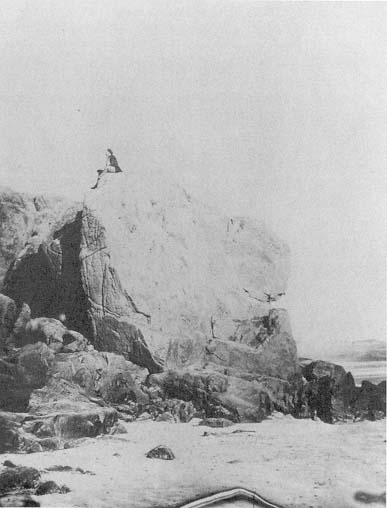

Plate 15.

Victor Hugo in exile. Hugo, in a carefully staged photograph, appears

perched on the "rock of the banned" ("rocher des proscrits") on the Isle

of Jersey, where he spent the first years of his exile before settling on the

neighboring island of Guernsey until the Second Empire came to an end in

1870. Not until "ideas, reason, progress, light" returned to France would he

return, he vowed, refusing the amnesty offered by Napoléon III in 1859.

He had to wait over a decade. On 11 September 1870, barely a week after

the proclamation of the Third Republic, Hugo entered Paris in triumph. It

took two hours and four speeches for the returning hero of republican resistance

and symbol of Paris to make his way from the Gare du Nord to his lodgings

near the Étoile. (Photograph by Charles Hugo-Auguste Vacquerie from the Musée

Victor Hugo, © 1993 ARS, N.Y./SPADEM, Paris.)

reading of Les Châtiments, the poems written against the Empire, the proceeds of which would purchase a cannon to defend Paris against the Prussians. And nothing could be more logical than naming the cannon in question the Victor Hugo.[9]

The politics of performance ill serve the practice of everyday politics. Hugo's political career, taken in narrow terms, could not be called a success. Theatricality did not play well within the (comparatively) narrow confines of the Assemblée Nationale to which Hugo was elected in 1848 and again in 1871. The eloquent speeches before the Assemblée Nationale reached no effective audience. In fact, scarcely a month after his election in 1871, he resigned. A bid for reelection later that same year failed miserably. He was vilified, and his house attacked, for opening his home in Brussels to Communards escaping France. He had stood against—against the Empire, against Napoléon III—and from afar. When it came to maneuvering in the arena of practical politics, in the corridors of the Assemblée Nationale, Hugo was at a loss. His grandiloquence moved hearts; it did not pass laws or engineer the programs of a new society.

It is no wonder, then, that Hugo dwells so exclusively within a symbolics of protest over one of explicit social reform. His central symbol is the Bastille, though not the Bastille placed or remembered as much as the Bastille destroyed. The fall of the prison that symbolized every injustice is the equivalent of many another cultural birth. "Athens built the Parthenon, but Paris tore down the Bastille," Hugo writes, fully confident that the negative juxtaposition makes a triumphant claim. That he makes such a contention in the introduction to Paris-Guide (XVIII) testifies to the centrality of a revolutionary politics in his conception of the city. These politics center on a spatial absence, or the place where the Bastille no longer stands, in a city where Hugo, in exile, no longer lives.

This conundrum of absence also suggests the problem of a politics of performance geared entirely to protest. What could come after successful remonstration in 1870? Hugo, though not his fellow deputies in the Assemblée Nationale, found the answer in his own stupendous identification with Paris. Just as he remained the quintessential Parisian through every moment of exile, so every Parisian could know the glory of the Revolution through the empty space of the Bastille. It was the radical idea of Paris and not the social agenda to be performed there that drew Victor Hugo and sustained his work.

Yet the politics of performance served Hugo, and the republic, well. His inability to cope with practical politics, his ineffectiveness in parliamentary maneuvers—paradoxically, these failings made him an even more powerful symbolic figure. Hugo had stood against the empire. Hence he stood for the republic. Which republic? Whose republic? Hugo stood for the broadest ideology of the republic. Precisely because he could not be restricted to any particular political party or program, he could be appropriated by a Third Republic that had begun under such inauspicious circumstances and that needed legitimacy in a continuing context with both the right and the left. The now legendary Hugo, with republican credentials that none could contest, provided an alibi for those who squabbled over the new political directions to be taken. As on the rock at Jersey, Hugo could be seen from afar. Physical distance, translated into psychic terms, defined Hugo within the contemporary society. The same prophetic stance of Notre-Dame de Paris, which foresaw 1789 from 1482, turned the older writer into the patriarch of the Third Republic, one who viewed contemporary events from above and beyond immediate context.

The sense of remoteness from the present came all the more easily in the striking contrast between the Paris that Hugo left in 1851 and the aggressively modernizing city to which he returned twenty years later. The Paris to which Hugo returned in 1870 was a city transformed. At issue, beyond the comparatively simple matter of moving stones and streets, was a whole new relationship of self and space. Much of the topography would have been unrecognizable. Stranger still, no doubt, was the urgency of change. Haussmannization had recast the city into a dazzling modern and markedly different form. The metropolis of the Second Empire, the frenetic city of La Curée, had replaced the city of L'Éducation sentimentale and Hugo's own Les Misérables, the Paris of the July Monarchy that Hugo knew so well.

Especially in light of Hugo's convictions concerning the inextricability of the political and the literary, it was inevitable that the politics of performance would inform his later writing as well as his public persona. Moreover, it is symptomatic that in none of the major novels about Paris—Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), Les Misérables (1862), and Quatrevingt-treize (Ninety-three ) (1874)—does Hugo deal with contemporary Paris directly. In each case Hugo reads the contemporary city through a vision of the absent city of the past. "The outline of old

Paris shows up under the Paris of today," he writes in Paris-Guide, "like an old text in between the lines of the new" (x). More succinctly than any other single statement, this definition of urban intertextuality correlates text and topography.

Paradoxically, the intertext, old Paris, offers a more powerful means of comprehending the current text, the Paris of the present. As Notre-Dame de Paris fashioned a Paris for the July Monarchy, and Les Misérables for the Second Empire, so Quatrevingt-treize would construct a city for the Third Republic. As the first novel integrated the Revolution of 1830 into Parisian history and the second made a July Monarchy for the Second Empire, so Quatrevingt-treize produced a scenario incorporating the Terrible Year of 1871 into the Third Republic. In this novel the politics of distance performed a revolution made to measure for the Third Republic, a revolution that belonged to a Paris triumphant, a Paris that could keep as its motto the "Fluctuat nec mergitur" that Haussmann had bestowed on it. Hugo's Paris refuted the Commune and at the same time reaffirmed the Revolution. The writer offered a city that harmonized the contradictions of the new republic. "Madness on both sides," Hugo pronounced in April 1871, well before the final disaster. "But France, Paris and the Republic will come out alright."[10]Quatrevingt-treize takes on an impossible task. It seeks to reconcile the irreconcilable by turning the Terrible Year to positive account. With a gesture more audacious still, Hugo restores the monarch deposed by 1871—the Paris created and crowned by the Revolution.

II

L'histoire a sa vérité, la légende a la sienne.

Hugo, Quatrevingt-treize

History has its truth; legend has its own.

The dilemma posed by the excesses of 1793 had long concerned Hugo. As early as 1841, in his speech upon entering the Académie française, Hugo painted a positive portrait of the Convention Nationale, the legislative assembly that condemned the king to death in January 1793 and authorized the Terror in the months that followed. He began gathering material for Quatrevingt-treize as early as 1863, well before the Terrible Year. Yet Quatrevingt-treize is very much a novel

of the moment. Hugo scrupulously notes in his diary the date he began writing: 21 November 1872. Ironically, this novel too was a work of absence, written at Hauteville House, that is, the home on Guernsey in which the writer had spent most of his years of exile, where he had written, among many other works, Les Misérables, his novel of the Restoration and the July Revolution. Here as before, Hugo seems to have been able to conceive Paris best by removing himself from the complexities, and the distractions, of the contemporary city.

The challenge of 1793 for any appreciation of the Revolution is to account for the founding event of modern France by accepting its least acceptable moment. To define the Revolution by and through 1789, as Hugo did in Notre-Dame de Paris and in the introduction to Paris-Guide, raised few problems, certainly not for Hugo, who never wavered in his belief that Paris owed its place in history to the destruction of the Bastille. Clearly, though, the year of 1793 required different tactics; violence on all sides sullied the ideal of the revolution. The execution of the king that opened the year ("the legend of the 21st of January seemed tied to all of its acts," as Hugo would note in Quatrevingt-treize ),[11] the governance of the Committee of Public Safety, the summary justice dispensed during the Terror, the war against the Allied forces in the east, and the civil war in western France—altogether these events constitute a year fully as "terrible" as any Hugo had lived through, including 1871.

The novelist needed to refurbish the ideal of the Revolution, and in order to do so, he needed an interpretation that would transcend the ideological divisions of the present and provide common ground on which the republic could build. Translated into his writings, the politics of performance showed up in the novel as a politics of transcendence: "Above revolutions truth and justice remain like the starry sky above the storm" (171). "Above" was Hugo's preferred point of vision; his was the eye of the bird in flight that moved across space, the vision of the prophet who ranged across time. At issue are the points of intersection between the political and the literary. Quatrevingt-treize fulfills the dual political and literary engagement that drove Hugo's entire career. This novel is, in sum, Hugo's legacy of the Revolution to the republic. Once again Hugo consolidates existing political equations into a re-vision of the political landscape.

Quatrevingt-treize recounts the dramatic tale of the Vendée, the metonymy that then, as now, designates the counterrevolution of the 1790S fought by an alliance of royalists and peasants in western France in the Vendée and in Brittainy just to the north. For Hugo, writing from the vantage point of 1872, the revolt was a lost cause that provoked ferocious cruelty on both sides, "savagery against barbarity" (177). At the same time, the Vendée was "a prodigious phenomenon," another example of the union of contraries "so stupid and so splendid, abominable and magnificent" (181). Hugo personifies the epic confrontation of the royalist Whites, led by the marquis de Lantenac, against the republican Blues, led by his grandnephew, the exvicomte Gauvain. The Blues carry the tricolor flag and swear allegiance to France and to the republic. The Whites and the ignorant Breton peasants remain faithful to the king, to the church, in a word, to the past. "To understand the Vendée, one must imagine this antagonism: on the one side, the French Revolution, and on the other, the Breton peasant. . . . Can this blindman accept this light?" (18182). The fundamental problem is one of vision. The Revolution literally lights up the dark forests in which the peasants live almost like animals, in caves, in the bush, in one instance in the hollow of a dead tree.

The Revolution also carries this light forward in time from the Enlightenment (the "Age of Lights" for the French language) and outward from Paris (the "City of Lights," as French culture has conceived it). Although almost four-fifths of the book takes place in Brittainy, part 2 ("In Paris") occupies a pivotal place in the novel because Paris determines the course of the Revolution and, hence, contains the future. What is 1793?, Hugo asks in his usual grand rhetorical style: "'93 is the war of Europe against France and France against Paris" (118). One could scarcely imagine a more succinct definition of 1870-71 . Hugo continues with the question that figures the entire book, "And what is the Revolution?" The answer Hugo gives to this constitutive question makes it clear that the present—1871—contradicts the past: "It is the victory of France over Europe and of Paris over France," a conquest that explains "the immensity of this terrible minute, '93, greater than all the rest of the century" (118).

Despite the relatively few pages taken up by events in the capital, the opposition Paris-France structures the entire novel. Hugo's summary highlights both the double generic reach of Quatrevingt-treize,

which comprehends epic as well as tragedy, and its dual periodicity, which includes the subtext of 1871 as well as the text of 1793. "Nothing more tragic," Hugo notes early on in the novel, "Europe attacking France and France attacking Paris. A drama that has the stature of an epic" (118). Once again, Hugo's visionary sense reveals to him the palimpsest of history. No writer is more conscious that every text is simultaneously an intertext that makes sense only within the larger network. So too every regime reaches backward and forward to other regimes. Hugo's distinctive vision of history is precisely that history is a vision. In the introduction to Paris-Guide, Hugo the historian reads backward, from the contemporary city to the old. In Notre-Dame de Paris and Quatrevingt-treize, Hugo the prophet reads and writes forward, from the old city, and the old regime, to the new. But Hugo's novel, like history, like the city, like the Revolution that it produces, holds both the old and the new.

The metaphors and images that carry the novel leave no doubt of the victor in this monumental battle of light against darkness, good against evil, and, more curiously, compassion against the exigencies of revolutionary justice. The present will necessarily triumph over the past. The only question is how to represent the struggle so that the necessary outcome also appears as the right outcome. Quatrevingttreize makes yet another gesture in a politics of transcendence. Hugo attains the necessary distance from the quotidian by constructing the novel around the dramatic confrontation of contraries, by "sublimating" the individual into the cosmos, and by "naturalizing" social and political phenomena. All three strategies are characteristic Hugolian modes of textuality. Here, in the context of the Terrible Year, each operates to produce a politics, and a text, of transcendence that sets the Revolution back on course and on site, in Paris.

Perhaps the most striking example in Quatrevingt-treize is the treatment of the Convention Nationale, the legislative assembly that governed France from 1792 to 1795. It is for Hugo the "visible envelope" for the revolutionary idea, through which materializes "the immense profile of the French Revolution." Too long, Hugo asserts, has this key moment in the Revolution been misunderstood by "myopic" judges, who can see the "abyss" and "the monster" of the Terror but not the "sublimity" of the "prodigious phenomenon" that founded the First Republic. It is, once again, a question of perspective (150-51) It was also the stage for the Revolution. "Whoever saw the drama

[of the Convention] thought no more about the theater" (157). There was "nothing more deformed, nothing more sublime" (157), in the judgment that echoed the prescriptions Hugo had offered for romantic drama over forty years earlier, "a pile of heros, a herd of cowards" (157). Hugo depicts the workings of the Convention as a battle of words as "violent and savage" as the war being waged in Brittainy (156). The epic combat between right and left pits a "legion of thinkers" against a "group of athletes" (157).

Hugo builds his own drama from just such antitheses, which contend only to create a higher synthesis. "Antithesis," he argues, "is the great organ of synthesis; it is antithesis that makes light." In Enlightenment terms, that light is not an artificial creation of the intellect but a product of nature.[12] The Convention produced the revolutionary synthesis effected by the confrontation of opposites. "Even as it was bringing forth the revolution, this assembly was producing civilization. A furnace, but also a forge. In this cauldron where terror was boiling, progress was fermenting" (167). The mechanical metaphors are hardly accidental. Friction and combustion produce light, enabling a revolution on the technological no less than on the political plane. The alibi and the justification of the Convention and, by extension, of its acts, always come back to its place in history as an agent of progress. To substantiate the association of the Convention with modernity Hugo lists its many decrees, from the abolition of slavery and the establishment of free public education to the new codes of uniform weights and measures and the Institut de France. Of the 1 1,2 10 decrees of the Convention, Hugo proudly reports, two-thirds had a humane rather than a narrowly political goal.

As in Notre-Dame de Paris, Hugo operates within a visionary mode of history. To convey the immensity of the revolutionary phenomenon he frequently reaches beyond history to myth. The Convention is a corn batant in the eternal war of light against darkness as it struggles against the "hydra" of the Vendée that it carries in its entrails and the heap of royal tigers on its shoulders (168). Yet, because this myth plays out in specific historical circumstances, it is, properly speaking, neither myth nor history but legend. For his novel Hugo claims this truth of legend. "History has its truth, legend has its own" (181).

The rhetoric in which Hugo indulges—the great use he makes of antitheses, the outsize, even grotesque images, the litanies of names

and events—is the linguistic resource by which he recasts history into legend. The dramatization of the Convention, the synthesis of opposing ideologies, the dissolution of ideological contraries into a larger, comprehensive whole, have the effect of depoliticizing this most political of institutions. The litany of names ends up obscuring their differences. The product—modern France and the civilization that it incarnates—justifies the production; the end justifies the means.

The political is depoliticized still further by the transformation of individuals into types whose archetypical status is stressed by continual reference to classical heroes. The youthful, wise, and brave Gauvain is likened to Hercules (204), to both Alcibiades and Socrates (205), to Achilles (219), and to Orestes (227). In a mother seeking her kidnapped children, Hugo sees Hecuba. And so on. The even more forceful Christian model moves the individual still further beyond the narrowly historical. Gauvain is patently the christological martyr who sacrifices himself to save humanity and, here, to redeem the Revolution. Plainly not entirely of this world, Gauvain acts as the agent of a superior force. His followers see him as a Saint Michael who, as in all the images of this local Breton saint, will triumph over the hydra of the Vendée (168, 345). The scaffold frames a veritable apotheosis in the "vision" that transforms Gauvain into an archangel surrounded by a halo (379). In Hugo's eschatology, Gauvain's sacrifice enables the Revolution to move beyond 1793, beyond the deadly strife incarnated by the marquis de Lantenac, on the one side, and Cimourdain, the emissary of the Committee of Public Safety, on the other.

The Christian model, in turn, is sublimated into a vision that encompasses all of nature. The insistent comparisons between the individual and the natural, between the social and the cosmic, assimilate the quotidian into the cosmic, into nature itself. The Convention is a mountain top, a Himalaya (150), a wind, an ocean wave (170-71). The most striking example of this naturalization of the political and the historical is the extended confrontation of La Tourgue, the medieval tower that is the ancestral Breton home of Lantenac and Gauvain, and the guillotine, the efficient modern machine of death that has been transported from Paris. The one is the emblem of feudalism, the other of the Revolution; the one represents a dogma, the other an ideal; the one is a monster of stone, the other a monster of

wood. Hugo offers his historical explanation through the grotesque, which makes the guillotine the necessary product of the tower. Constructed of wood, the guillotine is a "sinister tree" that has grown on the land, watered by the sweat, blood, and tears of every tyranny. Hence the guillotine "had the right" to say to the tower: "I am your daughter"—a daughter who is therefore a matricide (376). The present time is "a tempest," a "great wind" that delivers civilization from the "plague" by which it was afflicted. The "horror of the miasma" explains the "fury of the wind" (372). Piling up image upon image, each more overblown than the last, Hugo justifies the Revolution even in its greatest excess. Quatrevingt-treize, finally, is politics as cultural performance.

III

La révolution est une action de l'Inconnu.

Hugo, Quatrevingt-treize

Revolution is an action of the Unknown.

"I am not a political man." Gauvain's response to Cimourdain's reproaches of failing to heed the dictates of political expediency (229) could very well be Hugo's. His politics too, were cosmic, transcendent, larger than life, certainly larger than the social order. In exile the writer saw himself as he later represented Gauvain, as a martyr: "There must always be someone to say: I am ready. I sacrifice myself."[13] Hugo's revolution is an "idea," "an action of the Unknown" (170), in which individuals participate but whose outcome they do not effect. "What must pass passes" (171). In the Hugolian universe the very notions of guilt and innocence no longer obtain. "No one is innocent, no one is guilty" (231), in Gauvain's words. "Events dictate, men sign." Desmoulins, Danton, Marat, Grégoire, and Robespierre are only scribes. The true author is God (171).

Yet, even though absolved of responsibility for events, the individual must answer to God for his actions. "What does the storm matter," Gauvain observes in a moment of exaltation, "if I have the compass? What do events matter if I have my conscience?" (372). Hugo situates political action on the level of individual conscience. Nevertheless, Gauvain's sacrifice is necessary for the Revolution to move

beyond '93 to the future. Will Hugo's sacrifice have a similar effect in 1871?

The defining struggle of Quatrevingt-treize is only secondarily the battle between the Blues and the Whites; though it commands the story line and supplies extraordinary scenes, that war is almost epiphenomenal. Metaphor after metaphor, image after image, speech after speech, ensure that the Revolution can only win. Is it not "a form of the immanent that presses upon us from all sides and that we call Necessity?" (171). Even though he goes free at the end, Lantenac cannot win. He is the past, and the past must yield before the winds of change. La Tourgue, the emblem of feudal tyranny, must lie in ruins at the end, and it does.

Yet there is vital political debate in the novel, and it is this debate that makes Quatrevingt-treize a novel for the 1870s. The victory of the republic is assured, but the nature and, hence, the course of that republic remain in doubt. The fundamental conflict of the novel is not the opposition between the Blues and the Whites but the contest within the camp of the Revolution, the blue of Gauvain against Cimourdain's red flag of revolution. How would the tricolor of the republic combine the three colors? Would the Revolution rally around Gauvain's republic of mercy or Cimourdain's republic of harsh justice? "The republic was winning . . . but which republic? In the coming triumph two forms of republic faced each other, the republic of terror and the republic of clemency, the one wishing to conquer by rigor and the other by kindness. Which would prevail?" (226)

Such was the question that Hugo posed for the Third Republic: How would it treat the Communards? The savage repression of the Commune translates into the subjugation of the Vendée. But Paris is incomparably more important, precisely because of the connection with the Revolution. For him at any rate, his condemnation of the empire excused crushing civil dissent; the engendering of the republic justified every cost. A tempest sweeps clean. Notwithstanding his support for the Third Republic, Hugo, like Gauvain, chose compassion against strict justice. That he thought the Commune "idiotic" did not keep him from issuing a public notice immediately after the destruction of the Paris Commune that he would open his home in Brussels to Communards fleeing France. (Whereupon the Belgian government obliged him to quit the country.) In 1876, 1879, and 1880 he made formal pleas for amnesty in speeches before the As-

semblée Nationale.[14] The novel of 1874 makes the same case. Clearly, Hugo sides with Gauvain's "republic of the ideal" against Cimourdain's "republic of the absolute." "Your republic," Gauvain tells Cimourdain, "measures and regulates man, mine takes him into the sky" (368). Gauvain envisions a society that is "nature sublimated," that places equity above justice, that makes men and women equal, that strengthens a prosperous France. This revelation of the future in 1793 concerns the future in the present, the future that is the present in 1871.

Quatrevingt-treize places the legitimacy of the Third Republic in the rejection of Cimourdain's republic of the sword (371-72). Cimourdain's suicide—he has no arguments to oppose Gauvain and shoots himself at the very moment that the blade of the guillotine falls on Gauvain—acts out the failure of his conception of relentless justice. There may be no immediate effect. The novel simply ends with the double execution-suicide of Gauvain and Cimourdain: "These two souls, tragic sisters, flew off together, the shadow of the one mingled with the light of the other" (380). Nevertheless the choice must be made, and made anew at each juncture. The performance of Quatrevingt-treize forces this question upon the reader. With which republic will the vote be cast? The tour de force of the novel consists in its insistence on the starkest, Manichaean terms. Hugo offers a choice rot among diverse political positions but between good and evil, between light and darkness, between the future and the past. The ultimate contraries will be resolved in heaven.

Put another way, the future is on the side of Paris. The city forces the choice that Hugo presses. Hugo does not simply associate Paris with the Revolution, he defines the city by the Revolution. In its turn the city defines the Revolution. And that city exists beyond topography, the city of ideas, the city of an idea—the Revolution. If the Revolution is an ideal in search of a "visible envelope" (151), Quatrevingt-treize is that envelope. The novel stabilizes the Revolution by containing its movement, and it dramatizes the Revolution by giving it form. Like Notre-Dame de Paris forty years earlier, Quatrevingttreize views Paris from afar. The first novel is dominated by views from above the city, from the top of the cathedral or from various undetermined points in the sky; the second is viewed from Brittany, where most of the novel takes place, but more importantly, from the point of view of the end of '93, the end of the Terror, the end of the war

in the Vendée. Hugo observes that when they voted the execution of Louis XVI in January 1793, Robespierre had eighteen months to live, Danton fifteen months, Marat five months and three weeks. Thus the end of the Terror is contained in its beginning just as the end contains the beginning. The guillotine that has been sent to Brittany will return to Paris, where, in carrying out the murderous decrees of the Committee of Public Safety, it will also end the Terror. The future is in the present. Gauvain's vision of the future republic is already written in the terrible events of the present, the republic of compassion originates in the republic of terrible justice, that is, where it first becomes a necessity. Paris will swing back, for it is "the enormous pendulum of civilization; it touches in turn one pole and the other, Thermopylae and Gomorrah" (115).

IV

La Révolution littéraire et la Révolution politique ont fait en moi leur jonction.

Victor Hugo, Océan

The literary Revolution and the political Revolution have joined in me.

The power of Hugo's portrait of Paris in Quatrevingt-treize lies in its idealization and in the way that the city, like the Revolution, is placed beyond dispute. Personification is no longer adequate to render the idea of Paris that sustains this novel. Hugo forswears the traditional images of Paris. The most grandiose personification cannot convey the immensity of the city. By 1874 Hugo's Paris is an idea, the idea of the Revolution that Hugo dramatizes in Quatrevingt-treize. (Literally as well, since '93, the dramatic adaptation of 1881, had over 100 performances.)

A further comparison with Notre-Dame de Paris illuminates the striking transformation in Hugo's conception of the city. Forty years, two failed revolutions, and an extraordinary metamorphosis in the city as place separate the two novels. Notre-Dame de Paris is a novel of urban places, a novel that hears and sees and feels the city. Notre-Dame de Paris bespeaks the optimism of 1830 that produced the myth of Paris, the sense of discovery of the city, its present and its history. It is this myth that sustains Balzac's artist-flâneur as he takes hold of the city,

explores its furthest reaches and lays bare its secrets. Notre-Dame de Paris too stages the city. Despite the 348 years that separate Hugo's Paris of 1830 from the Paris of Claude Frollo and Quasimodo, Notre-Dame de Paris is firmly anchored to place. Strongly delineated particular places structure the novel: the cathedral in the center of the city that centers the novel; the Latin Quarter, where the students throng; the Place de Grève, where Quasimodo is pilloried and Esmeralda is hung; the Court of Miracles, the city-state within the city governed by the band of gypsies; and, finally, brooding over all, the prison-fortress of the Bastille. Notre-Dame de Paris gives life to the stones of the city. Hugo even claims the origins of the novel in the mysterious inscription that he saw carved in a stone within the cathedral. Notre-Dame de Paris not only reads the old Paris beneath the new, it resurrects the old text in the new. The new Paris that we see is the city of this text as well as the topography before our eyes. "For those who know that Quasimodo existed," Hugo maintains, "Notre-Dame is today deserted, inanimate, dead."

The Paris of Quatrevingt-treize utterly lacks this sense of place. Its primary space, as the title indicates, is not topographical but chronological. The Revolution that Notre-Dame de Paris foreshadows, Quatrevingt-treize enacts, but the revolution is peculiarly detached from the city in which it is nevertheless incarnated and in which it originates. Where the Revolution foreshadowed in Notre-Dame de Paris is fixed in the city by the Bastille, the Revolution in Quatrevingt-treize is embodied by a distinct and movable object, the guillotine. The mobility of this instrument of revolution figures perfectly the mobility of the Revolution itself, an idea that can take hold anywhere. Modernity and the Revolution are rendered by movement and thought. The Convention as Hugo presents it in Quatrevingt-treize is an endless flux of words; "intemperance of language reigned" (169), speeches multiplied. Continual movement submerged the contributions of the individual members, "even the greatest" among them. "To impute the revolution to men is to impute the tide to the waves" (171). The chapter entitled "The Streets of Paris in Those Days" begins with a paragraph lasting almost five pages in which Hugo endeavors to encompass the sense of public life in revolutionary Paris through a succession of sentences and phrases beginning with the impersonal "on" and rendered in the imperfect. The reader comes away with a sense

of perpetual motion, of effervescence, a sense of movement, not of site.

People used to live in public, they ate on tables set up in front of doorways, the women seated on the church steps made bandages while singing "The Marseillaise," the Parc Monceau and the Luxembourg gardens were drill fields . . .; No one seemed to have time. Everyone was in a hurry. . . Everywhere newspapers . . . On all the walls, posters, big, small, white, yellow, green, red, printed, handwritten, where one read this cry: Long live the Republic! (111-14 )

Hugo had long associated the Revolution with movement. The whole of Notre-Dame de Paris is structured by the opposition of the medieval civilization imprinted on the cathedral and the modern civilization that will come from the printing press (see bk. 5, chap. 1, "Ceci tuera cela"). Any number of images and metaphors contrasts the stasis of the cathedral, where knowledge is bottled up in the secret researches of Claude Frollo, with the volatility of the printed word. The word will eventually bring down the Bastille just as the guillotine will vanquish La Tourgue. The marquis de Lantenac does not have Hugo's sympathy, but he voices Hugo's belief in the power of the word. "When I think," the marquis laments, "that none of this would have happened if Voltaire had been hung and Rousseau sentenced to hard labor" (352). "No scribblers! as long as there are Voltaires, there will be Marats" (353).

The triumph of print is assured and the connection to revolution is confirmed because movement is life. Thus Hugo ties his properly sociological and political analysis of the connection between the printed word and revolution to his belief in nature and the eternal forces of the divine. The word is, for Hugo, the ultimate manifestation of the divine: "Words are the Word, and the Word is God" ("Suite" à la "Réponse à un acte d'accusation"). Hugo's identification with the movement of the word, his belief in the efficacy of the printed word, inevitably detach him from that which is fixed. The writer inhabits words not places. Moreover, the words that he inhabits—better still, the word by which he accedes to a higher realm—necessarily detach him from place. Paris is powerful less as a place that individuals inhabit than as an idea that produces the words of revolution. Whence its power. "Paris, being an idea as much as a city, is ubiquitous."[15]

The staggering self-confidence of Hugo in these matters may keep us from appreciating an important truth. The story of Paris and its

place in his thought is peculiarly enabling both as device and resource. All of his assurance flows from his recognition that Paris is both place and idea, both context and word. Only by accepting Hugo's utter faith in this power of the word can we understand the extraordinary claim that "the literary Revolution and the political Revolution have joined in me."[16]Quatrevingt-treize stages this juncture. Whereas the introduction to Paris-Guide historicizes the Revolution as idea, Quatrevingt-treize dramatizes the movement that propels the idea. For both texts, Hugo writes from the distance of the far removed Hauteville House, and in both instances he has chosen exile. Thus the imperatives of performance drive a mythology that is at once personal and historical and a rhetoric that requires for its effect the excessive, the monumental, even the monstrous. The Terrible Years of 1793 and 1871 were all of these. Quatrevingt-treize contains the Terror, and it does so by proposing a cosmology in which evil is a temporary but vital, even positive, element in the good that necessarily follows. The city of progress, this novel reassures us, will itself progress and will carry that progress to the world beyond. In this way Hugo not only fuses literature and revolution, as he claims, but also subsumes both into the encompassing myth of Paris.

V

AUX MORTS DE 1871.

À tous ceux qui, victimes de l'injustice sociale, prirent les armes contre un monde mal fait et formèrent, sous le drapeau de la Commune, la grande fédération des douleurs,

je dédie ce livre.

JULES VALLÈS.

TO THE DEAD OF 1871.

To all those who, victims of social injustice, took up arms against a poorly made world and formed, under the flag of the Commune, the great federation of suffering,

I dedicate this book.

JULES VALLÈS.

If for Victor Hugo 1871 was an intellectual challenge, for Jules Vallès the Terrible Year, and most particularly, the extraordinary two months of the Commune, was the high point of his life, the year when, as he tells it in the autobiographical novel L'Insurgé (1886), he "had

his day."[17] Born in 1832 and therefore still in school in the provinces during the Revolution of 1848, Vallès was prevented from manifesting his opposition to Louis-Napoléon's coup d'état of December 1851 by his father, who had him forcibly interned in an insane asylum. During the Second Empire, Vallès lived a more or less precarious existence as an opposition journalist. In 1870, after the fall of the empire, the socialist Vallès actively opposed the newly proclaimed Government of National Defense and, in the newspaper that he founded in February 1871, stridently refused the armistice that the government had concluded with the Prussians. Elected to the Paris Commune in March, Vallès was from then on, arguably, the most vocal of its leaders, particularly for the immensely popular journal that spoke for the Commune, Le Cri du peuple. Barely escaping the appalling repression of the Commune in May 1871, he spent months hiding in Paris and in the provinces and then fled first to Belgium and then to London, where he spent most of the next nine years. Condemned to death in absentia by a military tribunal in July 1872 for his participation in the Commune, Vallès could not return to France until July 1880 when, after many years, several tries, and much debate, the Assemblèe Nationale finally voted full amnesty for all of the Communards. The day after he received a telegram announcing the news, Vallès left for Paris, so that he arrived in Paris in time for the first official celebration of 14 July as the national holiday.

Like Hugo, though in a very different mode, Vallès was what he himself called, in one of the neologisms that make his work a linguistic delight, a "parisianizing Parisian" ("Parisien parisiennant", 2:1394). There are other parallels with Hugo. Both men died the same year, 1885, Hugo at a great age (he was born in 1802), Vallès a full generation younger. More than the accident of their contemporaneous deaths connects Hugo and Vallès. Most important, for both writers, revolution was a guiding principle of their lives and their work; and, again for both, revolution meant the Paris that Vallès called "this classic land of rebellion" (2:1394). Finally, both engaged the Terrible Year in texts that are all the more significant for the very different conceptions of literature, of politics, and of Paris that they dramatize. There is a temptation to take the two as polar opposites: Hugo the living republican legend, glorified during his lifetime; Vallès, the down-and-out and invariably fractious journalist who managed to get himself in trouble with every kind of authority, a rebel by

Plate 16.

Portrait of Jules Vallès by Gustave Courbet (1860). Eleven years after

his portrait of the young but already well-known Vallès, Courbet joined

the opposition journalist in the Commune. Vallès spent a decade in

exile after the bloody repression of the Commune in May 1871, and

Courbet spent six months in prison for his complicity in the destruction

of the Vendôme Column during the last days of the Commune.

(Photograph courtesy of Giraudon / Art Resource, N.Y., from the

original held by the Musée Carnavalet, Paris.)

nature even more than by ideological conviction. As he proudly insisted of himself, "I am a rebel. And a rebel I remain" (2:91).

The funerals of Vallès and Hugo reinforce the contrast. Hugo's state funeral in June 1885 was a majestic ceremony that is inevitably invoked, then as now, as the tribute paid to the powers of great literature. Hugo himself would have appreciated the dramatic contrasts of the event. Following a lying-in-state for a night under the Arc de Triomphe, where the poet-patriarch was attended by an honor guard of young poets, Hugo was borne to his final resting place in the hearse reserved for the poor as he himself had directed for the final performance of a life structured by drama. The government respected the letter if not the spirit of his wishes. The hearse of the poor was attended by the National Guard and paraded down the ChampsElysées before crowds of two million or more. The poet was buried in the Panthéon, the Church of Sainte-Geneviève that the First Republic had transformed into a secular burial ground to honor great men of the republican age and that the Third Republic reinstituted for Victor Hugo. With a vast diffusion in the popular press, Hugo's funeral was one of those rites of passage by which French literary culture celebrates itself and proclaims its existence to French society at large.[18] Indeed, for the drama and exaltation of the moment, there is no better account than that given by Maurice Barrès in his novel of 1897, Les Déracinés, in a chapter aptly entitled "The Social Virtue of a Corpse."

Vallès' death in February of the same year was a very different affair, although it too gave rise to a demonstration. It was manifestly sectarian as Hugo's was not, a demonstration of the solidarity of those who had fought with Vallès in what he called in the dedication to L'Insurgé "the great federation of sorrows" (2:875). According to Le Cri du peuple, the journal that Vallès had founded two years before, some sixty thousand Parisians followed this hearse of the poor, with perhaps two hundred thousand to three hundred thousand spectators lining the streets along the way. Vallès was buried, not in the Panthéon, but in Père-Lachaise, the cemetery located in the northeastern working-class section of Paris and closely associated with the memory of the Commune. On the edge of this cemetery, in front of the Mur des Fédérés (Wall of the Communards), an infamous massacre of Communards had taken place. Père-Lachaise was a fitting resting place for Vallès. It was the cemetery of his idol Balzac as well as the

site of the executions, and it would eventually be the cemetery for a number of notable Communards and socialists (including Karl Marx's daughter Laura Lafargue and her husband, Paul, founder of the French Workers Party).

Politics directed Vallès' life, although, curiously enough, he was not much more of a politician than Hugo. He embraced his notoriety as a political journalist and scorned the very notion of the man of letters who placed himself beyond the everyday and the political. He did not undertake his great Jacques Vingtras trilogy until his exile in London, and L'Insurgé, the final volume, did not appear in full until after his death in 1885. Still, his politics, and the literary works that went with them, did not fit in with the practice of the Revolution that the Third Republic worked so diligently to establish. The figurative as well as literal "pantheonization" of Hugo bespoke the insecurity of the regime and the political necessity of fixing on a symbol of unity within a republican tradition above suspicion. At the same time, the Third Republic sought to distance itself from the First and Second Republics while still declaring itself the nominal successor. Republicans of the 1870s were haunted by the tumultuous politics and the ultimate failures of the First and the Second Republics, each of which ended in a coup d'état by a Bonaparte. The nascent and still shaky Third Republic had to claim and to disclaim the Revolution simultaneously. It had to convince France (and the world) that, while fulfilling the promise of the Revolution, it was not itself a revolutionary regime.[19]

In its search for unimpeachable heroes, the Third Republic looked for figures connected to but not directly involved in the Revolution. Like the First Republic it turned to Voltaire. As the First Republic staged a great ceremony for the transfer of Voltaire's body to the Panthéon in 1794, so the Third Republic almost immediately turned the boulevard Prince-Eugene (named after the son of Napoléon III) into the boulevard Voltaire, placed Voltaire's portrait in every town hall in the country, and in 1878 staged a vast centenary celebration of his and Rousseau's deaths. Similarly, Victor Hugo offered a precious asset to the Third Republic by virtue of his simultaneous association with the Revolution and independence from any identifiably revolutionary activity. Like Voltaire, Hugo embodied the Revolution without revolutionaries, an almost legendary event in the past that legitimated the present without constricting it.

With Jules Vallès the contrast could scarcely have been greater. For Vallès, revolution means practice in the present and through the present into the future. Revolution is not an event, it is a state, a phenomenon that can never be assimilated into a society that remained, as the dedication to the novel L'Insurgé proclaimed, "ill-made." All of Vallès' work and this novel in particular declare the Revolution unfinished business. It is hardly surprising that a republic in search of stability should studiously dismiss Vallès' politics of presence or that it should reject the texts sustained by such an understanding. What is perhaps less obvious is why it has taken so long for Vallès to get much of a hearing in our own time, when Hugo no longer offers a viable literary model. Even at the time of his death Hugo was a survivor of an earlier age, his work relegated for the most part to the musty nineteenth century. (Reference is almost invariably made to the flip answer of the young André Gide when asked to name the best poet of the nineteenth century: "Victor Hugo, hélas!") Modern poetry descends from Baudelaire not Hugo; twentieth-century prose looks to many models but not often to the grandiloquence of Hugo. The cultural figure is less easily displaced. Sartre's recollections in Les Mots of his grandfather's cult of Victor Hugo testify to the tenacity of that figure. Today as well, Victor Hugo lives on in textbooks and anthologies as a cultural reference and a nineteenth-century icon.[20]

More than age is in question. Hugo was not simply thirty years older than Vallès. He was a literary giant, the most celebrated of the heroic line of romantics who had decisively shaped the literary field that Vallès entered in the 1850s. After Hugo, after Lamartine and Vigny, after Balzac, no writer would, or could, dominate the literary world as they had. In the 1850s, of the pioneers of the 1820s only Hugo continued to be a vital force. His stature continued to increase at a time when the others of his generation were either dead (Balzac) or in semiretirement (Vigny, Lamartine, Sand).

Despite governments that kept a vigilant eye on every publication, the continuing expansion of journalism made it an ever more powerful determinant of place in the literary field as well as a significant source of income for aspiring writers. The introduction of advertising made it possible to lower subscription rates and paved the way for the serialization of novels to attract readers for the advertisements. The same Émile de Girardin who came up with the idea of coupling advertising and the serial novel in the 830s turns up in L'Insurgé in the

1860s as a quite extraordinary, immensely powerful (and not entirely antipathetic) figure in the world of letters: a cat, in Vallès' extended metaphor, that always lands on his feet and is always on the lookout for prey, "a man all nerves and all claws who has pushed his paws and his muzzle everywhere for the past thirty years" (2:902). Vallès' Girardin comes straight out of Balzac's great novels of journalism. This sense of a society and a literary world of constant struggle does much to explain why Vallès the journalist looks to the royalist Balzac for a model rather than to the revolutionary Hugo.

This journalistic world was largely peripheral to Hugo and his career. Hugo was not a journalist but a man of letters who wrote for reviews and journals only occasionally. Although he founded a journal with his brothers in 1819 (Le Conservateur littéraire ) and another with his son in 1849 (L'Événement ) Hugo placed himself in the nobler species of man of letters. Vallès kept himself firmly in the world of journalism; Hugo burst onto the literary scene at the age of seventeen, when his poetry was awarded a prize by the oldest extant literary academy in France, the Académie des Jeux Floraux. If Hugo offered Vallès and his generation a model of the successful writer—and he assuredly did—it was a model that the younger generation knew it could not possibly emulate.

Nor, in Vallès' very strong view, should it do so. "Just as there is an out-of-date politics, there is a sterile and dangerous art, living off crumbs, sleeping on debris, that has to be relegated to the catacombs" (1:883). The writer, the artist, must write in the present, not the past. They have to have "felt and seen what they want us to feel and see" (1:891). For the true artists who are of their time, and who have been actors in the debate, Vallès coins the term "news-er" ("actualiste"). Perhaps, he says, the word has no future, but at least it has no past; "and I am not for the past" (1:891). Writing in 1857, Vallès contends that the second half of the nineteenth century needs a new politics, and it needs a new poetics, a poetics of prose. Romanticism "tolled the death knell" of poetry (1:9). "A new society, with other emotions, other sentiments, other weapons, . . . has opened the second half of the 19th century; what was beautiful yesterday will be ridiculous tomorrow. You have to move with the times." It was time, Vallès announced with his usual truculence, to give up poetry and to "live in prose" (1:10). If Hugo would not have appreciated being targeted as the "pall bearer" at the funeral of poetry (1:9) and might

not have found Vallès' acerbic style especially congenial, he should have recognized in the combative Vallès of the 1860s the equally contentious Hugo of the 1820s and 1830s, who called for a new literature to fit a new society and boasted of having put a revolutionary's red cap on the fusty dictionary of the Académie française.

That the erstwhile revolutionary romantics had grown fat upon the land needed no more evidence than the performance of Hernani, Hugo's reputedly "revolutionary" play of 1830, when it was specially authorized for the World's Fair in 1867 (performances had been forbidden since Hugo had gone into exile). Vallès was not so faintly disgusted at the spectacle presented by the aging, corpulent romantics and the disciples they had produced: "Either romanticism has aged or, stuffed with fat, it has produced children with rickets" (1:949). Still and all, Vallès had to admit, these skinny second-generation romantics had a spot in the literary world, and he did not. It was incumbent upon Vallès—a "realist," as he identifies himself in the same article—to define success differently. That definition, in the literary world of the Second Empire, would come through journalism, which meant that it would come through politics. And those politics, for Vallès, were ultimately a politics of and for Paris.

VI

C'est donc Paris, Paris misérable et glorieux, Paris dans sa grandeur et son horreur . . . ce grand corps fiévreux.

"La Rue," La Rue

It is then Paris, miserable and glorious, Paris in its grandeur and its horror . . . this great fevered body.

In the assimilation with Paris, Hugo is a model, but again one that Vallès could not but oppose. When Vallès began writing in the 1850s, so forceful was Hugo's identification with Paris, on the one hand, and with political opposition, on the other, that Vallès could not escape the connection. The affective and ideological distance that Hugo maintained during the empire was denied to those on the scene, who had to deal not only with the instability of the quotidian but also with the particular circumstances of censorship and the other tribulations of literary life during the empire. Well before he joined the Commune, Vallès had a long history of run-ins with the authorities. An

impassioned lecture on Balzac brought him an interdiction from the Ministry of Public Instruction preventing him from speaking in public. He served two months in prison and paid a substantial fine for one article that the government judged incendiary, and for another was fired by the all-powerful newspaper magnate Émile de Girardin under pressure from the minister of the interior. Vallès' journals led a very precarious existence as they steered, with varying success, between the shoals of the censors.

In view of the obstacles encountered in actual literary life under the empire, Hugo had a relatively easy time of it. He maintained his credentials as a revolutionary by never having to put them into practice. The Hernani that caused so much ink to flow in 1830 appears to Vallès in 1867 no more than a pathetic substitute for a truly revolutionary work. The vast antitheses for which Hugo claimed divine example seem a pernicious rhetoric. "Let's not confuse a maker of antitheses with a leader of people. . . . M. Victor Hugo is only a superb monster . . . a hollow statue," so that to call Hugo a revolutionary "would be a lie and a danger!" (1:951). (A few years later, when he himself would be forced into exile, Vallès would express greater sympathy for Hugo.)

If Vallès' fixation with Paris was surely the equal of Hugo's, his Paris was a very different city. It was assuredly not the Paris of monuments. Indeed, Vallès criticizes the vast, multiauthored Paris-Guide for its excessive attention to monuments and institutions and, hence, the past. "All stones look alike," declares the narrator of L'Enfant, dismissing monumental Paris without a second thought (2:338). The aversion to monuments and statues is, in turn, part of a larger antipathy to anything or to anyone who claims to be larger than life—or to anyone for whom the claim is made.

The deflationary perspective that Vallès brings to such apparently diverse subjects as the past, nationalism, literary style, and governmental authority is distinctly modern and even modernist. "I don't believe in the Panthéon, I don't dream about the title of a great man, I don't care about being immortal after my death—I care about living while I'm alive!" (2:891). In the presentation of his journal La Rue in 1867, Vallès warns his readers that the journal "will attack all aristocracies, even those of age and genius" (1:939). Replying in the next issue to cries of outrage protesting just this comment, he makes the point with even greater force: "I want La Rue to show you fly-

catchers of glory ("gobe-mouches de la gloire") that there is no more need for providential men in literature than in politics" (1:941).

Although these barbs may not be aimed directly at Victor Hugo, Vallès makes it abundantly clear in a number of other articles that Hugo certainly fits the description of the "monumental" writer, the writer who preaches and "makes phrases for the pleasure of making phrases" (1:941). Even the largely favorable review of Quatrevingttreize Vallès writes in the Revue anglo-française reproaches Hugo for "bible-ized sentences" ("biblisme de phrases") that "drown the idea in shadow or dampen it in fog." The "solemn and vague manner" of the narrative fails to serve the "terrible precision" of the drama being played out. Finally, Vallès cannot help closing with an injunction to the "great poet" to stop talking to the clouds (2:79).

Vallès assuredly does not talk to the clouds. Against Hugo's aesthetic of the monumental, the transcendental, and the symbolic, Vallès proposes a very different aesthetic that is part and parcel of very different politics. Against Hugo's politics of performance, Vallès sets his own very personal performance of politics. For Vallès, the emblem of the city, the part that best expresses the whole of Paris, is the street, and it is the street that renders best the originality of Vallès' conception of Paris. The significance of the street for his work is patent. Vallès gave the name to not one but three journals that he edited (1867, 1870, and 1879), to a number of articles, as well as to two books (La Rue in 1866 and La Rue à Londres in 1884). He used "Jean La Rue" as a pseudonym. In fact, the most devastating criticism that Vallès can think of for the collection of poetry that Hugo published in 1865, Les Chansons des rues et des bois, is that the book "has nothing of the street: the title is a lie" (1:568). As movement, the city cannot possibly be represented by a monument. Jacques Vingtras knows very well why he dislikes monuments: "I like only things that move and shine" (2:338). In a later issue of Le Cri du peuple Vallès notes laconically that "we aren't in favor of statues." Why? The "petrification of a reputation conflicts with our ideas about the progress of the human spirit" (2:1094). "Fewer statues, more men!" (1:896) is the battle cry of this critic. Vallès nevertheless, if unsuccessfully, opposed the destruction of the column in the Place Vendôme with its statue of Napoléon.

The street has just the kind of movement that, for Vallès, marks true art. It is the repository of the human spirit, filled with just the

sparkle of life that Vingtras loves. It is not a place fixed and defined by externals but rather a space of circulation. "Originaux" and "excentriques," rich and poor, mix in a space that itself has no hierarchy. "Heaven forbid that I should establish hierarchies—I detest them!" (1:324). Vallès thinks of literature as he thinks of society and refuses hierarchy in the one as in the other. The movement by which the street is defined and the egalitarian principle by which the street is governed make this open space the paradigmatic expression of Vallès' literary practice and political commitment.

In contrast to the visionary mode of Hugo's characteristic bird's-eye view from the towers of Notre-Dame or from even further in Quatrevingt-treize, Vallès places himself, and his text, squarely in the street. Distance disables. Climbing to the top of the Panthéon, he gets dizzy (1:957). And when he goes up in a balloon, Vallès sees only the map of the city, not what he recognizes as the city itself (1:960). To write about the city, Vallès needs its streets. Escaping from France, having just crossed the border into Belgium, Vingtras turns back to look at the sky in the direction "where he senses Paris" (2:1087). Whereas Hugo deliberately distanced himself from contemporary Paris to write about the Paris of 1793, Vallès had to return to Paris to write his saga of Paris in the Terrible Year. The first two novels in the Jacques Vingtras trilogy, L 'Enfant (1881) and Le Bachelier (1884), could be written in exile, but L'Insurgé, the epic tale of the battles on and of the streets of Paris, required that the space be lived in the moment. The same need to experience directly the distinctive nature of urban space meant that to write La Rue à Londres Vallès returned to London.

An aesthetic of the street produces a politics of the street. The collective politics of the Commune as Vallès presents it in L'Insurgé are at the opposite pole from Hugo's politics of transcendence. Similarly, Vallès' participatory poetics stands against the prophetic stance that Hugo assigns to the great writer. In Vallès' version of the nineteenth century, every one of us can write a masterpiece if we will only write "frankly and simply." Then the "immense book of human emotions" written by all will replace the "monstrous work" made by those "who are claimed to have genius." No more "literaturizing literature" ("littérature littératurante") that only talks about itself. No more mysteries, no more great men, no more fixation on the Panthéon or the Académie française. Thus La Rue, as Vallès envisaged the journal, would not be "the paper of a few, but the work of every-

one." True to his conception of participatory poetics and to the logic of journalism, Vallès invited his readers to be as well "our collaborators and our friends!" (1:941, 942).

Vallès aims at being a very different kind of writer. Accordingly, he takes the side of a very different kind of literature. There have been too many "Victims of the Book," too many who believe what they read, too many who believe only through what they have read. "Not one of our emotions is direct." In contrast to Hugo's vision of the democratic utopia that would be initiated by the printing press, Vallès depicts a society where the book has taken over, where "everything is copied," and it is copied from a book. "The Book is there. Ink floats on top of this sea of blood and tears" (1:230).

The danger that threatens any book, the danger that Vallès strives to counter, is petrification. Vallès seeks a society, and a literature, without models, that will not be copies, that will not look to monuments, or books, in the past but will look around in the present. As a student with revolutionary aspirations he would look upon the Convention that executed Louis XVI and legislated much of modern France as the "culminating point of history," this "Iliad," and its actors "our fathers these giants" (2:481). The older Vallès, as convinced as ever of the necessity of working for the revolution, realizes that there is no point in copying the theatrical gestures of one's ancestors (2:907). The political problem facing the Commune is not to repeat '93 (2:926) (or, for that matter, 1789) but to invent the revolution, to produce a new society, and with that new society, a new literature. Above all, he assumed that the best literature in the best society required the city, a real Paris.

VII

II fallait une phrase, rien qu'une, mais il en fallait une où palpitât l'âme de Paris; il fallait un mot à Paris pour prendre position dans l'avenir.

Vallès, L'Insurgé

A phrase was needed, just one, but one in which the soul of Paris beat; Paris needed a word to take its position in the future.

Published in full only a year after his death, L'Insurgé is Vallès' political as well as literary legacy, both a statement of his political