I

Le flâneur peut naître partout; il ne sait vivre qu'à Paris.

Un Flâneur, Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un

The flâneur can be born anywhere; he can live only in Paris.

The flâneur first appeared in nineteenth-century Paris, an emblem of the changing city and the changing society, a product of urbanization and revolution. The figure takes shape over the first half of the nineteenth century, appearing under the empire, rising to exceptional prominence in the physiologies and character sketches that abounded under the July Monarchy, and suffering a radical dislocation at midcentury at the hands of Flaubert and Baudelaire. But the flâneur as we think of the figure today, the flâneur of everyday life, conveys none of the urgency with which writers in early nineteenthcentury Paris encountered the city and the society increasingly defined by that city. To recover the flâneur as the urban personage par excellence is to recapture a sense of the powerful tensions that govern the evolving urban context and to mark the writer's changing, ambiguous relationship to that context.

What is so remarkable about this figure is its progressive reevaluation. At the very beginning of the nineteenth century, when the flâneur first surfaces in urban discourse, the connotations are almost entirely negative. The inactivity that the July Monarchy will associate with a superior relationship to society is in the original usage a sign of intolerable laziness. A dictionary of "popular" (i.e., lower class) usage in 1808 defines "un grand flaneur" as "a lazybones, a loafer, man of insufferable idleness, who doesn't know where to take his trouble and his boredom."[2]

This flâneur is clearly Other and manifestly bourgeois, a distant cousin of René, whose insufferable idleness offends and importunes the lower-class speaker. But the term soon climbs the lexicographical and social ladder. The circumflex accent that the word usually acquires signals a redefinition through a change of perspective. Instead

of prompting a negative moral judgment, the flâneur's conspicuous inaction comes to be taken as positive evidence of both social status and superior thought. The flâneur grows into the rentier, in whose familiar, comfortable, and unthreatening contours the bourgeoisie can recognize one of its own. Thus solidly ensconced in the bourgeois world, and identified with the city, the flâneur is ready to be taken up and redefined yet again, this time by the writer for whom the flâneur's apparent inoccupation belies his intense intellectual activity.

The bourgeois flâneur does not make his first public appearance where he is usually placed, in Balzac's Physiologie du manage (1826) under the Restoration. In fact, Balzac is already working with a well-established urban personage and practice. The anonymous pamphlet of 1806 that introduces the flâneur seems to have escaped the notice of literary historians and lexicographers alike. The thirty-two-page Le Flâneur au salon ou Mr Bon-Homme: Examen joyeux des tableaux, mélé de Vaudevilles presents Monsieur Bonhomme, better known "in all Paris" as the "Flâneur."[3] The "Historical Preface" detailing M. Bonhomme's daily rounds in Paris is followed by a series of "Petites Réflexions" that pass in review a number of the paintings exhibited in the current Salon held at the Louvre. Nothing hints at the quite extraordinary literary fortune the flâneur was to enjoy thirty years later, and nothing alerts the reader to the emblematic nature that the flâneur would acquire as the urban personage par excellence of the middle third of the nineteenth century.

It is true that M. Bonhomme does not much resemble his successors. He is a dull creature, easily recognizable by his wig, his "Jansenist" style hat (broad-brimmed, plain), and his dark brown suit. A man of the ancien régime (he refers to the Place de la Concorde by the name it carried prior to 1792, Place Louis-XV), M. Bonhomme exhibits none of the intensity that will distinguish the relationship of later flâneurs to the city. In contrast to these "modern" flâneurs, who celebrate the joys of coming upon the unexpected and the untoward, M. Bonhomme makes the same rounds every day and checks in at the same places. Instead of the mysteries of the urban spectacle in which the latter flâneur will revel and the cultivation of the unexpected, M. Bonhomme reassures through the regularity of his routine.

Tedium must have done him in. Despite protestations that "the race of flâneurs shall not perish!" and promises of second, third, and "even 100" sequels, LeFlâneur au salon did not meet with the requisite

success. The promised sequels apparently did not materialize. A close analogue turned up a few years later with Jouy's immensely popular journalistic Hermit series that inaugurated the vogue of what I have called literary guidebooks. It would not be surprising if Jouy, a well established and widely published author at the time, was trying out a new formula in the 1806 pamphlet. Certainly, the lineage is there. The article entitled "Le Flâneur" in Les Francais peints par eux-mêmes does not hesitate to count the Hermit (along with Mercier) among the flâneur's long line of distinguished ancestors.

Nevertheless, M. Bonhomme displays the primary traits of the flâneur, namely, his detachment from the ordinary social world and his association with Paris. The essential egoism of the flâneur requires the first; the variety of his observations dictates the second. Like Jouy's Hermit, the flâneur is solitary by choice, a bachelor or widower (or else, as the flâneur-author for Paris, ou le Livre des cent-et-un puts it, he thinks and acts as if he were one or the other). He walks through the city alone and at random. Companionship of any sort is undesirable, and female companionship is especially so. Women, it seems, cannot maintain the detachment that distinguishes the true flâneur.

Later, under the Restoration and the July Monarchy, when commercial arcades (les passages ) were transforming the practices of the city street, the perils of shopping loomed large, and these arcades were, then as now, inevitably associated with women (Physiologie du flaneur, chap. 15). The shopper's (and the seller's) intense engagement in the urban scene, the integration into the commodity exchange, and the consequent inability to maintain the proper distance from the urban scene preclude the neutrality and objectivity cultivated so assiduously by the flâneur. The flâneur desires the city as a whole, not any part of it. No woman can disconnect herself from the city and its seductive spectacle. For she must either desire the objects spread before her or herself be the object of desire, associated with and agent of the infinite seductive capacity of the city. The flâneur's movement within the city, like his solitude, points to a privileged status. But because a woman is defined by the (male) company she keeps, to be alone is to be without station. Mobility renders her suspect. Balzac makes the case eloquently if hyperbolically in Ferragus, where the sight of the elegant Mme Jules unattended, and on foot, in a notoriously infamous street immediately compromises her reputation (5:796). Women figure the observed, they cannot possibly

reverse roles to join the observers. Women are indispensable to the urban drama that the flâneur observes, to the conjectures he makes, and to the tales that he tells, not the least of these ventures. There are, and can be, no flâneuses.[4] The flâneur's constitutive disengagement from the city ties this urban personage to the larger urban discourse, as practiced notably by the literary guidebook. For, like the authors of literary guidebooks, the flâneur strives to describe the city and also to understand how it works. The familiarity with the city that we can see the flâneur acquiring is assumed by the literary guidebook. We should then not be surprised to find a guidebook that appropriates the authority of flâneur. The flâneur's very text inscribes his relationship to the city. The author's random walks in Le Flaneur (in two editions, 1825 and 1826) provide the model for the book, composed in the spirit of flânerie "without plan, without order, without method." As it was with Mercier and would be with Vallès in their tableaux of Paris, the writer's own observations—"everything [he has] observed, as objects presented themselves to [his] eyes"—guarantee the authenticity of the text. For this "moral and philosophical exposé," the author of Le Flaneur "consulted no work," asked for no advice.

At the same time the flâneur as urban personage becomes one of the arresting phenomena that the literary guidebooks take it upon themselves to discuss. Both Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un (1831) and Les Francais peints par eux-mêmes (1842) devote chapters to the flâneur, and the craze for physiologies produced the inevitable Physiologie du flaneur in 1841. Yet none of these fixes the flâneur. Consider the difference between the flâneur and the devil who serves as titular figure of the literary guidebook. As the model taken from Lesage requires and the numerous frontispiece engravings make clear, the devil looks at the urban world from on high. Symptomatically, "Un Flâneur," author of the article "Le Flâneur à Paris" for Paris, ou le livre des cent-et-un makes a point of distinguishing himself from Asmodée. He does not practice the "dangerous art" of taking rooftops off houses to reveal the secrets of private life. Rather the flâneur operates in public, outside. For he cannot exist indoors. Like a plant that would be killed in the greenhouse, the flâneur flourishes only in the open air. At the theater, he keeps to the relatively open space of the foyer, preferring not to shut himself up in the "prison" of the theater itself.

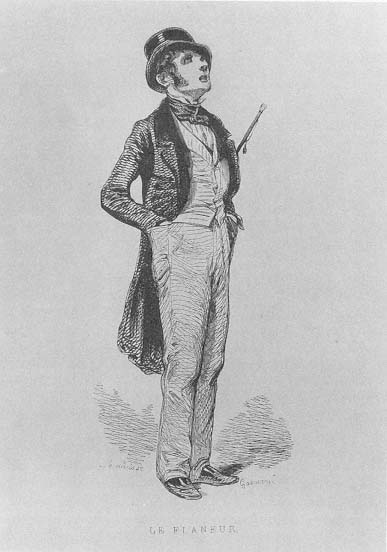

Plates 8, 9.

Flâneurs from Les Francais peints par eux-mêmes (1842). These

sketches by Henry Monnier (Plate 8) and Gavarni (Plate 9) give two

representations of the flâneur, a well-dressed bourgeois, cane in hand

ready to set forth in the city. In both renditions, one senses the

leisure, the satisfaction, and the spirit of reverie of an individual very

much in control of self and setting. (Photographs courtesy of Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Columbia University.)

Thus does the flâneur urbanize the observer, bringing him down to earth and plunging him into the urban spectacle. The devil looks down upon the city, the flâneur looks up and around and walks endlessly. (Good legs, as the Physiologie du flaneur reminds us, are essential equipment.) His field of predilection is the Paris of the arcades, the Paris of restaurants and boulevards and gardens, the Paris of crowds in public places. The reciprocity between the city and the flâneur is complete. "Without the arcades," Louis Huart admits in the Physiologie du flaneur, "the flâneur would be unhappy." But the balance tips in the other direction. For "without the flâneur the arcades would not exist" (chap. 13).

Unlike Jouy's Hermits, who themselves become personae in the city they observe—with dates of birth, specified places of habitation, definite habits and tastes—and unlike the dandy whose flamboyant dress sets him apart, the flâneur remains anonymous, devoid of personality, unremarkable in the crowd. It is in fact this undistinctive appearance that allows the necessary social distance. In short, the flâneur sounds very much like an author in search of characters and intrigue. Nights had always been mysterious; the flâneur's stories make days equally intriguing. As Huart reminds us in the Physiologie du flaneur (chap. 8), thinking perhaps of Balzac's Ferragus, a whole novel can spring from a single encounter observed in the street. There the chance meeting of the young, elegant, and virtuous Mme Jules and her secret admirer in a foul neighborhood leads to "a drama full of blood and love, a drama of the modern school" (5:796).

This bounding of the imagination and the intellect within a street setting both justifies the flâneur's literary claims and sets him apart from the vulgar idlers and gapers (badauds, musards ) with which the uninitiated might confuse him. Where M. Bonhomme accepted his relationship as "a very distant cousin" of "M. Muzard," the July Monarchy flaneur insists upon the difference. ("The idler apes the flaneur, he caricatures the flaneur and seems made to inspire disgust for flanerie," in the words of the Physiologie du flaneur, chap. 15.) He does not look, he observes, he studies, he analyzes. He is in sum a philosophe sans le savoir. "Flânerie," emphatically affirms Lacroix in Les Francais peints par eux-mêmes, "is the distinctive characteristic of the true man of letters."

Nowhere does the flâneur triumph more spectacularly than with Balzac. Although the flâneur's appearance in the very same year,

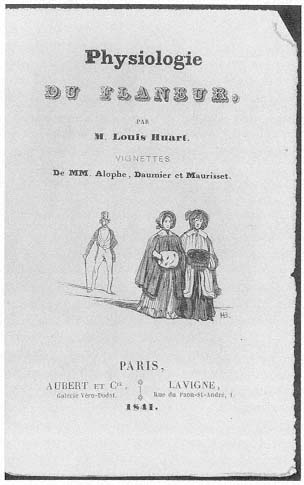

Plate 10.

Title page, Louis Huart, Physiologie du flaneur (1841).

This incarnation of the flâneur by Daumier emphasizes

the importance of the flâneur's gaze—a gaze that begins

in the activity of following women. (Photograph courtesy of

Special Collections, Butler Library, Columbia University.)

1826, in works as different as Le Flaneur, galerie pittoresque, philosophique et morale and the Physiologie du mariage testifies to the general familiarity of the figure during the Restoration, the honor of transforming the flâneur into a complete urban personage rightfully goes to Balzac. There will be more elaborate treatments of the flâneur but none more forceful than this first full portrait. Balzac's fervent celebration of the "flâneur artiste" set a model that would control for the next twenty years, not only for Balzac himself but also for the many other writers (and artists) who fixed upon the flâneur as a distinctive feature of modern Paris.

Whereas Le Flaneur, as a guidebook, more or less assumes the connections between the flâneur, Paris, and literature, Balzac forcefully articulates the dynamic involved. "To stroll is to vegetate, to flâner is to live." 'To wander about Paris—adorable and delicious existence!" The artist-flâneur cultivates a "science" of the sensual, a "visual gastronomy" (11:930). The superiority of the flâneur, which will become an article of faith in a very few years, already separates the true from the false flâneur, the true artist from the would-be creator. For like every other type in the Comédie humaine, the flâneur admits of more than one exemplar, each of which occupies a particular place within a hierarchy. The artist-flâneur of Balzac's Physiologie du mariage belongs :o a privileged elite, expression and manifestation of the higher, because intellectual, flânerie.

Other portraits—the vast majority—will at best be ordinary flâneurs, members of a "happy and soft species" (La Fille aux yeux d'or, 5:1053) given to random speculations and "silly conjectures" (Une double famille, 2:79). These onlookers in the city "savor at every hour its moving poetry" (5:1053) but will invariably be dazzled and bewildered and confused by the "monstrous marvel," "the head of the world." Although these ordinary flâneurs read the text of this "city of a hundred thousand novels" (Ferragus, 5:794-95), they are passive readers, taken up and taken in by the surface agitation and turbulence.

The overall distinction between the ordinary flâneur and the artist flâneur also bespeaks an underlying rationale for the whole category. The highest flâneur understands the city; the ordinary merely experiences it. Here, in other words, is one more indication of the great importance and the even greater difficulty attached to the process of actually comprehending the nature and meaning of modern Paris.

Aesthetically, the movement of the ordinary flâneur duplicates the same quality in nineteenth-century city life. Movement in the artist-flâneur is much more. It is a mode of comprehension, a moving perspective that tallies with the complexity of a situation that defies stasis.

To be sure, ordinary flâneurs are "the only really happy people in Paris" (La Fille aux yeux d'or, 5:1053). (The Physioloqie du flaneur proclaims the flâneur "the only happy man on earth," since no flâneur has ever been reported to have committed suicide!) Of course, as for the artist-flâneur, that happiness is contingent upon a more intellectual grasp of the incessant movement of the city and its seductions. This flâneur is the great exception to the rules that govern every circle of the Parisian hell that sets the stage for La Fille aux yeux d'or. For other figures or types, surrendering to the desires aroused by the city necessarily implicates them in the urban text, which they will not know how to interpret or turn to their advantage. Instead, the expert readers in the Comédie humaine— Vautrin Rastignac, d'Arthez, Mme de Beauséant—owe their skill precisely to their ability and willingness to remain both in and above the inferno. None succeeds entirely.

The walks about Paris that supply the artist-flâneur with material for study may well prove disastrous for the ordinary flâneur unable to maintain distance from the city and hence unable to resist its seductions. The original pejorative connotations of flânerie resurface to characterize the individual at the mercy of the city. Where the ostensible idleness of the artist-flâneur masks the vital intellectual activity of the true artist, the false artist is necessarily a false flâneur, whose inactivity derives from the inability to channel—that is, to use and comprehend—the desires roused by the city. In other words, the false artist lacks the detachment required for creativity. The Physiologie du flaneur rails against these loafers who proclaim themselves flâneurs. A policeman on the beat is more deserving of the name than the "incomplete artists" who never finish a painting! (chap. 15).

In Balzac's Paris, seeing is not necessarily believing, and superficial readers do not make good writers. Lucien de Rubempré in Illusions perdues quickly surrenders to Parisian brilliance and easy journalistic success. Once Wenceslas Steinbock quits the garret where Cousine Bette keeps him hard at work on his sculpture, he succumbs to the Paris that his success opens to him. Soon, Balzac notes, he joins the lowest order of flâneurs, who let themselves be determined by the city instead of mastering it. His is "the ultimate motto of the flâneur: I'll

get right to work!" Flânerie triumphs over every good intention: "Wenceslas . . . idled [flânait]" and before long becomes "an artist in partibus . ." (7:243, 449), thus fulfilling the prediction at the beginning of the novel. Bette knows full well that she must keep her sculptor on a leash, or else he will turn into a flâneur. "And if you only knew what artists call flâner!" her advisor tells her in a telling assimilation of the unproductive artist to the female spendthrift: "Real horrors! A thousand francs in a single day" (7:116). The true artists of t he Comédie humaine—the writer Daniel d'Arthez, the painter Joseph Bridau—are anything but indolent. Moreover, Balzac stresses their capacity to withdraw from Paris, their ascetic life, and their absolute commmitment to their work. Lucien founders because he is utterly unprepared for the hard work and the many difficult choices that creative work entails.

The artist-flâneur, on the contrary, tempers desire with knowledge. He masters movement after having engaged in it. Whether scholar, thinker, or poet, he is a connoisseur of the "pleasures (jouissances ) of Paris, one of a "small number of amateurs" who always have their wits about them on their walks, who know how to stroll as they know how to dine and to take their pleasures. In this fusion of science and sensuality lies the key to urban control. Unlike the ordinary flâneur, who is overwhelmed by the appropriately masculine monster (le monstre ) these "lovers of Paris" conceive of desire in terms of domination. Cette courtisane—or, only somewhat less obviously, a creature (une créature) and queen ("this moving queen of cities")—is logically ("naturally") subjugated by the (male) artist-flâneur. The conception of Paris as female is hardly new, but Balzac pushes the connection to its extreme by associating flânerie with carnal knowledge. Jouir ("tc enjoy," often with specifically sexual connotations) defines the flâneur's relationship to Paris in terms of desire as he "plunges his gaze into a thousand lives" (1:930). A manuscript of 1830 makes still more of the sexual resonance of the artist-flâneur's relationship to Paris. The city is "a daughter, a woman friend, a spouse" whose face always delights because it is always new.[5]

That creativity should be a function of control is evident in the power ascribed to the Balzacian narrator. An observer and also a participant in the city, a reader and also a writer of the urban text, the Balzacian artist-flâneur adroitly maneuvers distance and assimilation. Like the detective whom he resembles in so many respects, Balzac's

artist-flâneur situates individuals within the city. More significantly still, individual destinies lead to the city itself. "Every man, every fraction of a house" is a "lobe of the cellular tissue" of this "creature" whom the artist-flâneur alone knows so well (5:795). Here as in the birds'-eye views of Paris so popular in the 1840s, an "aesthetic of integration" bespeaks the strong narrative control for which synecdoche supplies the characteristic trope. The impossibility for any individual to take account of the multiplication of urban space is refuted by the artist-flâneur, the surrogate author who takes that unknowability and makes it a condition of creativity.[6] Nowhere is Balzac's fundamentally romantic conception of the genius more evident than in the flâneur turned narrator, a voice imposing his will on the city and its texts.