6

Judgments of Paris

Monument vengeur! Trophée indélébile!

. . . . . . ô Colonne française

"A la Colonne de la Place Vendôme," Victor Hugo

Monument of revenge! Indelible Trophy!

. . . . . . oh French Column

On 16 May 1871, allegedly under the watchful eye of Gustave Courbet, the Commune pulled down the great commemorative column in the Place Vendôme. Modeled on Trajan's column in Rome and topped by a statue of Napoléon as a Roman emperor, the 144-foot monument had marked the very center of Paris since 1810. Its seventy-six bronze bas-reliefs, cast from enemy cannons captured in battle, depicted the heroic actions of Napoléon's stupendous victory at Austerlitz in 1805. Marx predicted in The Eighteenth Brumaire that the statue of Napoléon would crash to the ground when Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte became emperor, but it took the fall of the empire to realize the prophecy. In the most obvious sense, the demolition of the column reenacted the fall of the Second Empire. Less obviously perhaps, the ruins of the column restaged the depredations of haussmannization, which had made rubble such a familiar sight in Paris. The fallen column reached at once to the new, modern city and to old Paris. Like the brutal urban renovations of the Second Empire that wiped out much of old Paris, the column strewn about the Place Vendôme figured the collapse of the city that writers like Hugo and Balzac and others had interrogated for a half a century and more. It spelled the end, as well, of Benjamin's capital of the nineteenth century. What Paris would replace it?

In Paris, as Victor Hugo observed in Paris-Guide, the old text invariably shows up under the new. And so it was for the Place Vendôme. The column erected in the middle of the square originally stood on a thirty-three-foot pedestal built in 1699 for an equestrian statue of

Louis XIV, once again in the obligatory Roman dress. That statue was torn down in 1792 and sent to a foundry, most likely to make cannons for the war against the Allied armies then besieging republican France. The statue of Napoléon I that stood atop the column in 1871 was just eight years old at the moment of its destruction. Inaugurated by Napoléon III, it was the third such statue of the emperor to top the column, the previous ones coming and going in accordance with the iconographic priorities of a succession of regimes.

Once again, politics reconfigured topography. And, once again, the changes are significant. The fate of the Vendôme Column, along with the controversies that it provoked, compressed into a single dramatic event the ideological strife that set France against Paris. In pitting republic against revolution in 1871, the government of the Third Republic set the stage for the end of revolutionary Paris. It was not simply that the Commune set itself against the republic and was repressed. The leveling of the Vendôme Column and the annihilation of the Commune that followed called into question the place, the identity, and the symbol system on and through which revolutionary Paris had been constructed. The mythic city of revolution so carefully elaborated over the century suddenly tumbled off its foundation.

The column exalted a long tradition of military prowess that linked the France of Louis XIV to that of Napoléon and identified both with Rome. From the ancien régime to the nineteenth century, military conquest forged important links between the various monarchies, republics, and empires that marched across nineteenth-century France. The name initially envisaged for the square—the Place des Conquêtes—would have been appropriate for every one of these regimes. Consequently, the statue of Napoleon that fell in the Place Vendôme in May 1871 was more than yet another monument destroyed. It stood, an d fell, like the Terrible Year as a whole, a powerful expression of the pervasive despair in the wake of the onerous armistice imposed by the Prussians and the ongoing civil war in Paris. For some, clearing the square promised new beginnings, for art and for society; for others, quite to the contrary, it dealt one more blow to the legacy of French military honor and glory that spanned the most divergent of political regimes. For Courbet, in particular, it led to a punishment absolutely without precedent. The painter had proposed dismantling the column several months before its actual destruction and, in ad-

dition to spending six months in prison, would actually be sentenced to bear the entire cost of restoration![1]

To explain this extraordinarily vindictive action compels us to consider the exceptional significance of this urban icon. With the scenes of military triumph that spiraled up the monument, the column narrated the history that it represented, yet another chronotope of nineteenth-century Paris that, like the master chronotope of revolution, merged time and space. As with the changes of street names during the Revolution and thereafter, the very volatility of this urban icon makes it an especially valuable evidence for the urban ethnographer. Like the rebaptisms of streets or the alterations of the city seal from one regime to the next, the shifting fortunes of the Vendôme Column show history at work in the construction of urban narrative.

If revolution supplied the master metaphor of nineteenth-century Paris, Napoléon provided the figure of legend. A potent force whether absent or present, the emperor's power was alternatively used and feared by his successors, from Louis-Philippe, who brought Napoléon's ashes back to France for burial in the Invalides in 1840, to Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, who based his bid for the presidency in 1848 on imperial filiation and who legitimated the Second Empire by cultivating connections with the First. But the Terrible Year did more than put an end to the Second Empire. Even though the statue and the column were back in place within two years, the heroic Paris that they exemplified had been vanquished. Like Napoléon I at St Helena, Napoléon III never returned from exile, and neither Napoléon II—the Eaglet—nor the son of Napoléon III ever reigned. The final defeat of the empire came not in 1815 on the battlefield of Waterloo but in 1871 with Paris in flames. The Communards who toppled the column and its statue were not attacking a single regime. In the column they aimed at all the old régimes of France in this memorial officially declared by the Commune as "a monument of barbarism, a symbol of brute force and false glory, a militaristic affirmation, . . . a perpetual outrage to one of the three great principles of the French Republic—fraternity."[2]

An integral part of Napoleonic glories, the city necessarily participated in the imperial defeat. Once again, Victor Hugo makes the connection. His ode "A la Colonne de la Place Vendôme," written in 1827 during the Bourbon Restoration, celebrates the "avenging

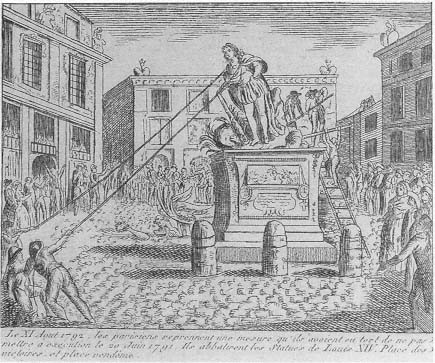

Plate 17.

Destruction of the statue of Louis XIV, Place Vendôme, August 1792.

This act, pulling down the original statue of Louis XIV that had stood

in place for nearly 100 years, was one of many during the Revolution

that set in place the idea of destroying the monuments of a displaced

politics. The Parisian palimpsest would emerge through a dynamic

interaction of tearing down and building up. ( Révolutions de Paris, no.

161. Photograph courtesy of Maclure Collection, Special Collections,

the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library, the University of Pennsylvania.)

Monument," "the indelible Trophy . . ." of this uniquely "French Column " In Hugo's vision, the scenes of military triumph that draw the spectator's eyes upward to the statue of Napoléon at the top keep victory vivid in French memory and remind foreigners of the power that France once was and might be again. Napoléon's victories, in Hugo's eyes, belong to all of France and to every regime. The Napoleonic eagle would not return—the Emperor had died in exile in 1821—but the "sun of Austerlitz" might well rise again; and the Bourbon lily would join forces with the republican Chanticleer, the Vendée with Waterloo.[3] The destruction of the column in 1871 finally

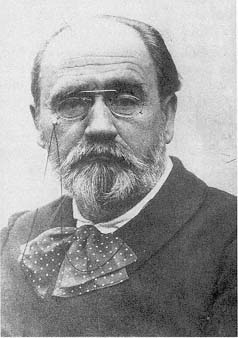

Plate 18.

Demolition of the Colonne Vendôme, 16 May 1871. In 1810 the

Colonne Vendôme was raised on the pedestal that remained from

the destruction of 1792 with a statue of Napoléon in Roman dress

at the top. Demolition of the 144-foot column, here in the very act of

tumbling, was an event much commented upon by both sides during

the Commune of 1871. Even though the Parisian icon that Victor

Hugo had called the "Monument of revenge! Indelible Trophy!. . . Oh

French Column!" was soon rebuilt, its demolition gave a final blow

to at least one of the myths of nineteenth-century Paris.

(Photograph courtesy of Roger-Viollet.)

brought the eagle down. It brought down as well the city in which Hugo could make the column a manifestation of country and characterize his own generation as so many "eaglets" bereft of a father.

The end of the romantic Paris of Hugo and Balzac also announced the end of the romantic writer. Although Paris remained the site of revolutions past, the city was no longer conceived or dreamed or, more importantly, practiced as the space of vast revolutions yet to come, hoped for or feared. The representative writer no longer took an identity through the Revolution. As observers at the time were not

slow to recognize, the defeat of the Commune deposed Paris. The Third Republic did its utmost to dissociate the present from revolution even as it harked to the originary moment of 1789. Thereafter, the Revolution and the city would make separate representations of country. The column was restored to the Place Vendôme, but the city in which that monument made sense could not be reenacted or restaged. At best, it was remembered. Like the city that arose from the Revolution and needed imaginative reconstruction at the beginning of the century, so too Paris at the end of the century, the defeated city, had to be rethought and reimagined. What could be the touchstone of Paris in the wake of the failure of revolution? What could be the master metaphor that would take Paris into the twentieth century?

I

lui, vaincu à Sedan, dans une catastrophe qu'il devinait immense, finissant un monde . . .

Émile Zola, La Débâcle

and he, defeated at Sedan, in an immense catastrophe, ending a world . . .

In the many forms taken by the reconfiguration of fin-de-siècle Paris, no writer better than Émile Zola illuminates the complex process of representational change.[4] Immensely prolific and most probably the best-known writer of the period, Zola undertook to rewrite the city as the century drew to a close. From La Débâcle in 1892 to Paris six years later, the novelist traced a route from the old Paris to the new, from the haussmannized Paris of the Second Empire to the metropolis of the Third Republic and beyond, to a vision of the twentieth century. In works that radically reconstrued the relationship of place and idea, Zola reformulated the connection between writer and space. He re-viewed the tie between the writers of Paris and the space that was their setting, their inspiration, and even their raison d'être. From Hugo, Balzac, and Vallès, who spoke from and to Paris as the place of revolution par excellence, the writer qua intellectual that Zola epitomized spoke from no place and addressed every place. Site no longer anchored the exemplary intellectual in anything like the way that the city of revolution fixed and directed the urban novelist early in the century. From La Curée and La Débâcle to Paris and the

Quatre Évangiles, Zola moved steadily to separate revolution from Paris.

La Débâcle is Zola's narrative of the Terrible Year. Where La Curée, written at the very moment of transition from the Second Empire to the Third Republic, straddles regimes, La Débâcle is unambiguously retrospective, coming as it does twenty years after the cataclysmic events that brought an end to the regime the writer had taken as his subject—the social and natural history of a family under the Second Empire. A year later Zola completed the family narrative with Le Docteur Pascal, but La Débâcle effectively terminated the social narrative. In this, his last judgment, Zola takes the final measure and ultimate representation of the regime around which the saga of the Rougon-Macquart family coheres. For La Débâcle fulfills the premises of the earlier works. The collapse of the Second Empire, Zola had already affirmed in 1871, is necessary to the very conception of the cycle. La Curée leads to La Débâcle as inexorably as the coup d'état of December 1851 brings the defeat of France in September 1870 and the massacre of Paris the following spring. The catastrophe and ruin that La Curée visits upon Renee Saccard are extended in La Débâcle to the city as a whole when Paris is thrown to the hounds of the German and Versaillais troops.

Debacle signifies more than the rout of French troops at Sedan on the eastern front. Within Zola's imaginative construction of the Rougon-Macquart cycle, the military defeat of France ends the regime without ending the narrative. The new regime dictates the fall of Paris, the fall of the revolutionary Paris incarnated in the Commune. Napoléon III is only the titular head of a recent regime of doubtful legitimacy. His abdication and exile finish the empire, but they cannot found the republic. As the true king of nineteenth-century France, Paris must be deposed to institute the republic. Another execution is in order.

Yet, obviously, France is inconceivable without Paris. Too many metaphors, too many images, and too many texts over several centuries insist upon the inextricability of city and country. Revolution sets Paris apart, but the end of the century rejects rather than embraces revolution. In 1870-71, the act of political and social formation takes place against, rather than for, the Revolution. The Commune realizes the hopes but also the fears of 1848, and its fate is the same. Once again, in a savagely ironic twist, a republic takes it upon itself to crush

revolution. Where Notre-Dame de Paris and Quatrevingt-treize imprint the Revolution on the city-text, La Débâcle effaces the Revolution from that same text. For Hugo's politics of transcendence in Quatrevingttreize, which merge revolution into a vast progression of history, Zola substitutes a politics of "naturalization" by subsuming the political into the eternal cycles of birth, growth, and death.[5] However different their modes of presentation and their understanding of literature, Hugo and Zola alike write political novels that set politics apart from the social and moral responsibilities of everyday life.

La Curée and La Débâcle are linked by more than the particulars of plot or setting or family interactions that tie all the novels in the Rougon-Macquart cycle. The exceptionally dense network of metaphors and images woven around Paris creates a specific intertextuality for these two novels. Zola's concern with disease and health, and his preoccupation with the reciprocal influence of heredity and milieu on individual and societal behavior, structure the entire novel cycle. But these novels of Paris give especial prominence to the tropes of disease, fever, debauchery, and madness to characterize not only the society and the individual but also, very pointedly, the rebellious city and its inhabitants. Whether at the top of Second Empire society in La Curée o r with the drifting population of malcontents in La Débâcle, Paris suffers from a malady that contaminates all of France. Renee Saccard is the sacrificial victim in La Curée, but the city continues the hunt, oblivious to the portents of the day of judgment that must surely come.

That day of judgment comes in La Débâcle. Thus the early descriptions of the emperor in La Curée and in the companion study of the Second Empire government, Son Excellence Eugène Rougon, reveal a man who walks with difficulty, his mouth opening weakly, a man with a half-extinguished eye and a dissolved, vague face. La Débâcle darkens the already somber picture of human dissolution. In the emperor who suffers from kidney stones and dysentery and flees into exile after surrendering to the Prussians, the reader recognizes the hesitant walk, the "dead eye," the "heavy eyelids," the "ravaged face" (84, 197, 312) of this man who has become no more than "a shadow of an emperor" (68). Similarly, La Débâcle realizes the destiny of Paris that is implied in La Curée as the city succumbs to the fever and folly adumbrated in the earlier work.[6]

La Débâcle chronicles the improbable friendship across class lines of the stolid peasant Jean Macquart, corporal in the French army, and Maurice Levasseur, one of his men, a bourgeois who, after the defeat at Sedan, returns to the besieged capital and sides with the Communards. As luck and the novelist would have it, Jean, who rejoins the regular French army that attacks the insurgent Communards, kills Maurice. For the peasant to rebuild the country, the Parisian must die, and the city must die with him. In the logic of the peasant close to the land that justifies the novel, "the rotten limb" (576) has to be lopped off in order for the organism to live. The vast enterprise of reconstitution of the country, in the literal as well as symbolic sense, cannot occur in Paris. To start that rebuilding, Jean Macquart quits the still smoldering city to return to the south that his family had left at the beginning of the Second Empire, "walking toward the future, toward the great and arduous task of rebuilding a whole France" (582).

The familiar associations of Paris—with a woman, with weakness, with intelligence—come together in La Débâcle to doom both Maurice and the city that he embodies and represents. Maurice "has his letters," having taken his law degree in Paris, and is, in contrast to the uneducated Jean, a "monsieur." Weak physically and temperamentally (25), Maurice is further endowed with a "woman's nervousness" (191).[7] France will be rebuilt by unambiguously masculine men, who, like Jean, come from and return to the country. So strongly is Maurice presented as an outgrowth, an emanation, of the city's own madness and fevers that the distinction between the man and the city all but disappears.[8] From the interpretive register of disease, La Débâcle moves to another, even stronger one in Christian allegory. In an image familiar from La Curée, the Paris of the Second Empire appears as Sodom and Gomorrah (562), the conflagration of Paris constitutes a holocaust (541, 576), the nation is "crucified" (576), and the "city of hell" (575) expiates its faults. To be sure, the biblical language is closely associated with the characters in the novel. But Zola's frequent recourse to free indirect discourse blurs the distinction between character and narrator. He assigns the images of disease, destruction, and punishment to individuals and also incorporates them into the narrative descriptions. We can never be sure just who is responsible for the images and metaphors or where they are to be applied as the point of view slides between narrator, character, and description.

The Commune thus deals the final blow to the Second Empire of Napoléon III and to the whole century that sprang from the first Napoléon. Maurice is the last, corrupt offspring of the empire. To the grandfather, the resounding victories of the Grand Army; to the grandson, the devastating defeat at Sedan and the depravity of the Commune. As Napoléon III perverts the legacy of Napoléon I, so too Maurice dishonors his inheritance. "This degeneration of his race . . . explained how the victorious France of the grandfathers could become the defeated country of the grandsons" (365). The military glories of the empire are evoked with ever greater poignancy as the defeats multiply (25, 71-73, 365). Notably, all of these defeats cohere for Zola in the destruction of the Vendôme Column. In the moment Maurice pauses to remember the litany of imperial victories from his grandfather's tales (541). The reader at the time most likely paused as well, to ponder the psychological investment in topography, an investment deepened by the intertexts that had accumulated over the century, from Hugo's original ode to his final protest against the demolition in "Les deux trophées" in L'Année terrible. With the sunset that ends the novel, a "bloody sun," the "sun of Austerlitz," sets for good, never to rise again. Nor will Victor Hugo write an ode to the restored Vendôme Column, to predict the rebirth of the Napoléonic eagle, or to enjoin the "eaglets" left behind, as Hugo called his generation, to keep the faith. As in Quatrevingt-treize, Hugo calls upon the French to resolve their quarrels as he resolves his antitheses: "Versailles has the parish, and Paris the commune. / Yet above them both, France is one."[9]

Yet, even as Jean Macquart looks at the sun setting over the city in flames in La Débâcle, he sees, or rather intuits, another dawn in preparation: "It was the definite rejuvenation of eternal nature . . ., the renewal promised to everyone who hopes and works, the tree that puts out. a strong new limb once the rotten branch . . . has been cut off"(581). The "new limb" cannot grow in the old Paris, in the degenerate Paris of the Second Empire where the revolutionary insurrection "grew naturally" (533). Somehow the ashes of the old city will fertilize the earth for a new city, a city without revolution. La Débâcle intimates a narrative of regrowth even as it recounts a drama of destruction and defeat. The Second Empire, in Zola's vision, destroys revolutionary Paris, not with the coup d'état of its beginning but in the apocalypse of its end. Politics recede before this vision of

a future that will come from the earth itself. The eternal cycles ordained by nature overcome the social institutions or political arrangements devised by humans.

II

Paris flambait, ensemencé de lumière par le divin soleil, roulant dans sa gloire la moisson future de vérité et de justice.

Zola, Paris

Paris was all ablaze, fertilized with light by the divine sun, turning over in its glory the future harvest of truth and justice.

The evacuation of the social and the political by the natural becomes still more pronounced in Zola's next cycle of novels, Les Trois Villes (Lourdes, 1894; Rome, 1896; Paris, 1898). Even more than La Débâcle, Paris splits between the city that is the setting and the city that is dreamed, both by various characters in the novel and by the narrator. With its antagonistic social classes, implacable anarchists, corrupt politicians, and decadent upper classes, Zola's republic of the 1890s resembles nothing so much as the Second Empire of the Rougon-Macquart. Zola's rare achievement in this novel is to have transformed this familiar city into something uncommon. Paris "deurbanizes" Paris by reconceiving the city as country. The return to the land on which La Débâcle places all hope is effected, paradoxically enough, in the reimagined and rewritten city of Paris.

In this naturalized Paris, revolution is a thing of the past, a distant memory of the failures of 1848 and 1871. Political action of any sort is a delusion. Instead of a model of democracy at work, the parliamentary debates of the Third Republic expose a morass of corruption, venality, and moral turpitude. At the opposite end of the political spectrum, Zola's anarchists place themselves outside society altogether. Their rage for destruction, wild dreams, and delusory mysticism tie the anarchists of Paris to the Communards of La Débâcle. In Paris too the "wind of violence" passes over the city in a "contagion of madness" (603), and the crazed dream of annihilation, the longing for a purified society and a "golden age" (566-67), produce a "chimera" (575). These hallucinations consume Guillaume Froment, the scientist, and his anarchist associates in Paris much as the "black dream" of destruction and the vision of a new golden age ravage

Maurice Levasseur and the Paris of the Commune in La Débâcle. But there is a difference. The fraternal reconciliation of Paris balances and overcomes the fratricide of La Débâcle. In a highly charged, overwrought scene in the crypt of Sacré-Coeur, the unfrocked priest, Pierre Froment, persuades his older brother, Guillaume, not to ignite the fuse that would explode the basilica and massacre the ten thousand pilgrims gathered for mass. The scientist must, Pierre insists, turn his scientific knowledge to positive account.

Guillaume Froment converts from the destructive vision of the anarchists to the pacific vision of beneficent science enunciated by the eminent chemist Bertheroy early in the novel. Politics, for Bertheroy, are totally irrelevant. Only science counts, for "only science is revolutionary" (476). The anarchists are "too dumb" if they think that bombs c n change the world. Is it possible, reflects Guillaume Froment, that this "singular revolutionary" actually works harder and more effectively than any anarchist, than any politician, to overthrow the "old and abominable society?" (476). The motor powered by Guillaume's explosive that purrs away to everyone's admiration in the final scene—here is the "real revolution" (604). Intellectual creation, not mindless destruction, engenders a new world. "Science alone is revolutionary, . . . beyond miserable political events, beyond the vain agitation of sectarianism and ambition" (605). Revolutionary Paris has moved full circle from the destruction of the Bastille as the primal, emblematic revolutionary act. Against Hugo, against Vallès, Zola removes revolution from the public space of the city and encloses it within the eminently private space of the laboratory, the workshop, and the home.[10]

Although Paris draws upon a number of the traditional images of Paris, Zola radically alters their sense. In affirmations that recall Hugo's impassioned statements of Paris-Guide, Zola's new city "rule[s] over modern times," "the center of all peoples," "the initiator, the civilizer, the liberator." In and through Paris the one century ends and the new one will begin (606). But Zola's city is not Hugo's. Its sovereignty no longer derives from the revolutionary tradition but from science. "Science . . . makes Paris, which will make the future" (477)

Paris is doubly powerful because it draws on the vitality of nature as well as the intellectuality of science. The city that Bertheroy perceives as a "boiler where the future is bubbling, under which we scientists maintain the eternal flame" (606) appears to Pierre Froment

as a vat or cask (cuve ) "where the wine of the future [is] fermenting."[11] Despite the obvious differences between the two containers—the one tended by the scientist, the other tended by nature—the two domains converge insofar as nature, like science, exists beyond conventional morality. The wine made in this cask is produced from "the best and the worst" (591), the dissolute no less than the pure. Zola invokes the image several times at the end of the novel to resolve, metaphorically at least, the moral dilemma that has beset Pierre ever since his trip to Lourdes and his subsequent loss of faith. In the long run and in spite of itself, the profoundly degenerate society that Zola condemns nevertheless does its part in the great work of nature. Revolution conceived as purposive, directed action disappears in a world no longer determined by Hugo's march of history but by the discoveries of science. Its conversion into a historical event relegates the Revolution to the past, a moment of preparation for the new century and its singular revolutionaries.

In redefining revolution, Zola reimagines the city. In place of the synecdoches by which Balzac and Hugo, even Flaubert and the earlier Zola, convey a powerful sense of the lived city, of the streets and the neighborhoods, of the houses and the shops, in Paris Zola detaches the idea, or the ideal, of the city from the urban site. True, the novel situates the action squarely in Paris, and we follow the characters all over the city, from the elegant neighborhoods of the rich to the squalid hovels of the poor. There is an amazing scene of a manhunt in the Bois de Boulogne that is characterized as a curée, and a moving narration of an execution in the Prison de la Roquette. But, in the end, the scrupulous location of familiar characters and their actions in an easily recognizable city counts for little. Zola's Paris lies elsewhere, in the space constructed by the metaphors that take Paris off location, off site—and beyond revolution.

Very much unlike that of writers who display urban topography as a means of leading the reader to an understanding of the city, Zola's metaphorization in Paris ends up denying the city as a distinctively urban space. Balzac and Hugo count heavily on metonymy for their portrayals of Paris. Notre-Dame de Paris is a synecdoche for Paris, which Hugo elaborates into a metaphor for the medieval city and the civilization that it subsumes. Even organic metaphors have an urban resonance. The notorious associations of Paris with a woman, and particularly a sexually aggressive woman, owe much to the readily observable prostitutes in the city streets. Or again, the metaphor of

Paris as the "head" of France appears especially appropriate in view of the concentration of French intellectual life in the capital. So too Zola in L' Ventre de Paris (1873), a novel about the central food market, takes the metaphor of the "belly" of the city to such an extent that it acts like a synecdoche. Then too, in L'Assommoir (1877) the constitutive metaphor for working-class life in Paris is suggested by the city itself. The bar called L'Assommoir which takes its name from the machine that dispenses the alcohol (assommer means "to beat up, to knock out") offers a striking and powerful example of metonymy veering into metaphor.[12] Indeed, the metonymic associations of many of the metaphors of Paris are what give that myth its characteristic intensity. Clearly, as well, the metaphor of "revolution" also draws its vitality on the associations with place.

When the metaphors of Paris begin to lose their metonymical foundation, because either the metaphors themselves change or the altered city fails to offer the places or the practices to generate the metonymy and ground the metaphor. Paris confirms this shift away from metonymy. The cask of wine, of which Zola makes so much as a metaphor for the city and the civilization beyond, and, later, the field have nothing to do with Paris. Lacking metonymical associations, they seem foreign, imposed from without, unjustified. They can almost be seen as anti-metonymies. Within an urban context the cask is surely an oddity if not an outright anomaly. Its associations are not with the city but with vineyards, the land, and the countryside. These associations with the land reconfigure both Paris and revolution and convert urban culture into agriculture. To the extent that the strength of the myth of Paris lies in the affinities between Parisian metonymies and metaphors, then the anti-metonymic force of Zola's metaphors undermines that myth. Zola simply discounts the public city and its narratives of corruption, seduction, venality, and misery—all traditional associations with the city, and, moreover, associations of which he had made much in earlier novels. Finally, what counts in Paris is not the familiar dramas of the public city but the very private drama of the ideal (and idealized) family that takes place within the home, within the artisanal workshop, that is, within the space of the novel itself.

Paris charts the inner voyage of Pierre Froment from doubt to a new faith, a voyage that takes him from the dark, cold city to the light and warmth of a field ready for harvest. Appropriately enough, given the solar logic of the novel, Pierre embarks upon his spiritual journey on

a dark, cold January morning in front of the Sacré-Coeur basilica on Montmartre. Alone, the priest tormented by uncertainty and the failure of human charity looks down at a Paris "drowned under a dreary, shivering thaw" under a sky "the color of lead," enveloped by "the mourning" of a thick mist (1).[13] Paris seems a "field of houses . . . a chaos of stones . . ., veiled with clouds, as if buried under the ash of some disaster . . ." (2). Notwithstanding the banality of the parallels drawn between life and the seasons as a literary strategy, the properly ideological nature of this vision is nevertheless remarkable. And Zola keeps Pierre in tune with the sun throughout the novel. The priest chooses "a bleak twilight falling on Paris" (380) to confess his anguish at his loss of faith. Not surprisingly, his future wife, the exuberantly healthy, tranquilly atheistic Marie, sees Pierre as "crazy" and suffering from "a black madness" (380). Pierre can emerge from uncertainty and darkness only in the brilliant, resplendent sun of a September day, surrounded by his family, with Sacré-Coeur resolutely out of the line of vision. "Paris was all ablaze, fertilized with light by the divine sun, turning over in its glory the future harvest of truth and justice" (608).

To connect the dark beginning and the luminous end Zola elaborates what turns out to be the constitutive metaphor of the book, by which Paris is transformed into a field planted by the scientist, nourished by the sun of truth, and to be harvested by all humanity. Paris moves from the almost sinister sterility of the church in the opening scene to the fecundity and productivity of the happy extended family at the end, from visions of the Last Judgment visited on the iniquitous city reminiscent of Maurice's "black dreams" in La Débâcle to a divination of the future reign of truth and abundance.

Zola does not entirely abandon more traditional associations of Paris. The panoramic view of the city that he surveys in the opening scene reminds Pierre, conventionally enough, of an "immense ocean," and the image recurs in one form and another a number of times throughout the novel.[14] But the defining image of the novel, which both charts Pierre's regeneration and contains Zola's vision of one century ending and another beginning, remains the field. The comparison is by no means original (although it is far less conventional than the ocean / sea parallel). Yet the weight that it bears in Paris makes the metaphor a distinctive interpretation of the city that gives striking expression to Zola's depoliticized politics for the Third Republic.

Four visions of the future, each closing a chapter and the fourth closing the novel, establish the field as the key to the novel and to Zola's revelation of a new Paris. The very first page sets up the movement of darkness to light and the transformation of the city that structure the book as a whole. The chapter opens on a grey, cold Paris day, but it ends with Pierre's dream of "a great sun of health and fecundity, which would make the city an immense field of a fertile harvest, where the better world of tomorrow would grow" (25).

His first visit to his brother's home on Montmartre gives Pierre a sense of what that Paris might be. Instead of the city of working-class poverty and upper-class degeneracy that he knows so well as a committed working priest, he finds his atheist, scientist brother and his three sons hard at work in a vast, open studio-laboratory. In place of the "terrifying" Paris and the "endless sea" to which he is accustomed, the late afternoon sun over the city outside the window discloses an endless field over which the sun seems to be scattering seed. The urban landscape of roofs and monuments covers the field, the streets become the furrows made by a giant plow. Is this, Pierre wonders, the planting that will lead to the future harvest of truth and justice?[15]

Later that spring, when Pierre has become part of the household, the scene recurs with still greater insistence on the connection between Paris and a field, between the sun and a planter sowing wheat. Zola renders spectacularly visual the associations of Paris with birth, germination, and growth that recall Hugo's introduction to Paris-Guide and his affirmation that "Paris is a sower" ("Paris est un semeur") [16] The scattering of the grains of wheat by the sun specifically implicates the Froment family (froment means "wheat") in the destiny of the city. And it is specifically the earth of Paris that will yield the longed-for harvest: "This good earth. . ., worked over by so many revolutions, fertilized by the blood of so many workers," is the "only earth in the world where the idea can germinate" (384).

The final scene in the novel brings together the three controlling images of Paris: the motor that turns Paris itself into a vibrating engine, alive and strong like the sun; the gigantic cask where the next century will be born; and finally, the field covered with wheat that now stands ready to be reaped. The time of planting is past. The light of science has engendered the motor ("the father and the son had given birth . . . to this marvel" [584]) as the warmth of love has pro-

duced Pierre and Marie Froment's child. So moved is Marie by the splendid sight of Paris in the sun that she "offers" her infant son to the city below "as a majestic gift." He, his mother prophesies, will harvest these Parisian fields and put that harvest in the granary. The novel ends in this apotheosis of the city transformed by nature and science. [17]

The concluding paragraph of the novel transforms Paris yet again, this time into a heavenly body, a lesser sun revolving in the universe, in tune with the divine laws of nature. The warmth of the sun that brings all life revolutionizes the City of Light by eliminating revolution. The City of the Sun succeeds the City of Light, Zola's Parisian fields replace the City of Revolution. The dreams of a new golden age that haunt the Communards of La Débâcle and the anarchists of Paris are impossible because they depend on an act of destruction. The new world is, for Zola, profoundly an act of creation.

In this manner, Paris affirms for society as a whole what Le Docteur Pascal (1893), the final novel of the Rougon-Macquart cycle, only suggests for the individual. The science defended as knowledge by the earlier novel is legitimated in the later work by the promise of a better society that it holds out for all humanity. The children born at the end of these novels speak to fundamentally different hopes. The fatherless infant alone with his mother in the last scene of Le Docteur Pascal becomes, in Paris, Jean Froment surrounded not only by an impressive extended family of parents, uncle, cousins, surrogate great—grandmother, and friends but also by three generations of scientists: his cousin Thomas (the inventor of the motor), his uncle, Guillaume (the discoverer of the explosive that powers the motor), and Bertheroy (the "master"). Surely, Jean Froment will make good on the combined pledge of his name, his family, his milieu—and Zola's very extended metaphor! The scientist will sow, and the next generation will reap. Indeed, the three novels of the Quatre Évangiles that follow Paris trace the reaping of that harvest, with the three younger sons of Pierre and Marie: Matthieu in Fécondité, Luc in Travail, and Marc in Vérité. (Jean was to be the protagonist of the unfinished Justice. )

And where is Paris after Paris? The force of the metaphor is such that the city all but disappears in the "luminous dust" (164), the "golden rain of sun" (383), and the "gold dust" (607) that suffuse the novel. The city of Paris would seem to be the antithesis of the misty, passably dreary city of L'Éducation sentimentale, its contours

clouded by the omnipresent rain, fog, drizzle, and haze. Yet, the glittering motes and specks of Zola's golden Paris achieve much the same effect of unreality, paradoxically dissolving the cityscape in an abundance of light. In these crucial scenes, the actual city of streets and monuments all but evaporates, whether under the moon's "calm dreamy light" that renders the city "vaporous and trembling," or in the morning sun that fashions a "city of dream" (467). The city of revolution, the city of historical events and monuments and politics, melds into the infinite field of grain, everything subsumed in a blaze of light.

The utopian impulse so evident in the determinedly apolitical yet highly ideological stance of Paris becomes even more pronounced in the novels that follow, which make even less place for Paris and a visionary conception of revolution. In the Quatre Évangiles Paris either serves as the traditional source of immoral ideas and depraved practices (contraception in Fécondité, the exploitation of the working class in Travail ) or is altogether irrelevant. The new society demands new sites: Chantebled ("Singing land"), the joyous, fruitful farm of Matthieu Froment's extended family in Fécondité; Luc Froment's cooperative industrial venture of Travail; and Marc Froment's public schoolrooms in Vérité.

In their exaltation of fertility, work, and education, Zola's modern gospels offer so many utopics—that is, texts that themselves constitute the ideal society, in a time and space that exist outside history and beyond topography. These novels are utopic chronotopes. But they are not, strictly speaking, "no place," as the term utopia implies. For all that they exist outside of contemporary society and ostensibly outside contemporary political debates, these works conceive and represent the future as a direct extension of the present.

III

Les hommes de littérature, de philosophie et de science, se lèvent de toute part, au nom de l'intelligence et de la raison.

Émile Zola, Declaration to the Jury

Men of literature, of philosophy and of science are rising from all over in the name of intelligence and reason.

This reconceived urban space at the end of the century, de-urbanized and de-revolutionized, produced a distinctive personage. As the

city early in the century produced its characteristic figure in the flâneur, so the very different Paris at the end of the century begat the intellectual. Although it by no means invented the intellectual, Zola's spectacular intercession in the Dreyfus affair unquestionably fixed the figure in the cultural repertory of modern France and the West. The debates began immediately, over who should be counted an intellectual, over whether the identification was a matter of individual choice or collective affiliation, and over whether, in the end, intellectuals, however defined, were a good or bad thing. At a moment of deep crisis in French society, Émile Zola thrust the intellectual to stagecenter, fueling on-going debates over the nature of contemporary society and the roles particular groups play within that society.

Much is made, and rightly so, of how unusual, and how unexpected, it was for this established writer—president of the Société des Gens de Lettres, Officer of the Legion of Honor—to take up the cause of the disgraced army officer and to embark upon a campaign that he knew would cost him dear (in the event, two trials, fines, close to a year's exile in England, suspension from the Legion of Honor, threats on his life, and public vilification that did not end even with his death). Neither the sympathy for the downtrodden and the oppressed evident in the Rougon-Macquart novels, nor the battles in defense of naturalism, nor again the spirited vindication of Manet would lead anyone to predict that this writer would set himself so intractably against the combined powers of the government and the army.

Even though Zola's action was unprecedented, he was not unprepared for the part that he undertook with such zeal. A close reading of Paris reveals, on the contrary, that the writer was in fact preparing himself for the role that he invested with such conviction and performed with such consummate skill. Although it would be excessive to see Paris as Zola's dress rehearsal for his engagement in the Dreyfus affair, the novel nevertheless provides strong evidence that the writer already possessed a firm sense of the special role that should devolve upon the intellectual in contemporary society.

A simple juxtaposition of dates speaks volumes: having completed Paris in August 1897, Zola entered the dreyfusard lists only three months later on 25 November, with an article in LeFigaro. The explosive "J'accuse" hit the newsstands the following 13 January. The novel was serialized during the fall and appeared in volume form in March, that

Plage 19.

Émile Zola at the time of the Dreyfus affair. The writer's impassioned defense

of the military officer condemned for espionage took the case out of the military

courts and put it before the civil courts and the public. If the novelist in

Paris could look with equanimity to "the future harvest of justice and truth,

" the intellectual who took up the cause of Alfred Dreyfus was not so patient.

His very metaphors, from a future harvest to an imminent explosion, show his

urgency, and suggest his complete identification with revolutionary rhetoric.

"J'accuse," Zola specified, was "a revolutionary means to hasten the explosion

of truth and justice." (Photograph courtesy of Roger-Viollet.)

is, between Zola's first trial in February and his second in July of 1898. Finishing Paris indisputably afforded Zola the time and the psychological space necessary for the Dreyfus adventure. Had he been in the middle of a novel, he later admitted, he wasn't sure what he would have done.[18] Still, it has not been appreciated how much this work has to do with Zola's intervention in the course of the Dreyfus affair—far more than juxtaposition of dates alone allows. For Paris proposes something of a blueprint for the model intellectual. This novel in which

Zola articulates the rights, the duties, and the mission of the intellectual prepares as it confirms the impassioned defense of Alfred Dreyfus. The dramatization of the intellectual coincides with the end of the revolutionary city, and Paris confirms both phenomena.

For Zola as for French society as the century draws to a close, the intellectual is a new figure, indisputably a product of modern society. In Zola's later work, representatives of intellectual milieux make a notable addition to the social classes recognizable from the Rougon-Macquart novels. The Dreyfus affair would reveal how modern the intellectual was. In contrast to earlier champions of justice, who typically spoke from a moral high ground, the intellectual also bases claims to a public hearing on knowledge. To take the most striking of Zola's predecessors in France (examples he had in mind), neither Voltaire nor Hugo claimed to know more than the authorities about the condemnation of Jean Calas, on the one hand, or the coup d'état that established the Second Empire, on the other. They knew more or less what everyone else knew but saw things differently. Accordingly, they make their case almost entirely on moral grounds. Of course, Zola passes a moral judgment. His strident rhetoric is overwhelmingly a rhetoric of morality. But he grounds that moral judgment in facts, in knowledge, or, to use the term to which he returns again and again, in "truth." In "J'accuse" (officially a letter addressed to Félix Faure, president of the republic), Zola assumes that Faure does not know the truth ("For your honor, I am convinced that you are ignorant of it") and needs only to be enlightened. The explosive list of accusations that gave "J'accuse" its name and provoked Zola's trials occupies fewer than two of the twelve pages of the letter. The rest retell the narrative of Dreyfus' condemnation, citing "facts" and making a "demonstration." Again and again Zola invokes "truth" as the necessary constituent of the justice that he demands for Dreyfus.[19]

The precise nature of the connection between the intellectual's moral stance and knowledge has been a vexed question ever since, usually revolving around the question of who is, or can claim to be, a bona fide intellectual. Why should membership in the inelegantly termed "knowledge professions" qualify one to speak on issues outside the realm of professional expertise? Contemporaries like the conservative critic Ferdinand Brunetière rebuked Zola for meddling in things that he had no reason to know anything about. In both cases,

judgment turned on the question of knowledge much as it would in innumerable instances in the twentieth century—the "truth" about the Soviet Union for the intellectuals of the 1930s, a different "truth" about the Soviet Union for the intellectuals of the 1970s.

Intellectuals dominate Paris. For in this novel haunted by the idea of the future, these representatives of modernity—the scientists, the scholars, and the professors—bear the burden of bringing the new century into existence. Guillaume Froment is an experimental scientist who works on his own, but the chemist Bertheroy (who most directly articulates Zola's faith in the beneficence of science) is a member of the Institut de France and lectures at the École Normale Supérieure, where Guillaume's son François is a student. The three sons cover several of the possibilities of this newly prominent social configuration: Thomas, the applied scientist (the motor is his invention), François, preparing to be a teacher-scholar, and Antoine, the artist.

Even the master solar metaphor focuses on the intellectual classes. The sun, explicitly equated with truth ("truth finally exploding like the sun" [590, of. 599]), singles out the Left Bank with all its schools, which "occupies a vast field in immense Paris" (200). In one of the structuring scenes of Paris as field, the rays of the sun fall alternately on the Latin Quarter with its great schools and on the neighborhoods of factories and workshops, thereby highlighting the alliance of knowledge and commerce necessary to bring the new era into existence (383). Further, Pierre Froment's conversion from the priesthood to the ethos of science clearly signals the shift in spiritual direction that society will and must take.

No matter what alliance is made, within the moral and social hierarchy established in the novel, it is nonetheless the intellectual who leads. Disinterested, unmoved by material considerations, the intellectual devotes himself to the common good. Guillaume will give his new explosive powder "to everyone." More than banter is at issue in François' self-conscious observation, as he watches the setting sun, that the École Normale and the Panthéon remain in the light long after night has plunged the commercial districts into obscurity (553). Politics fade before this unbeatable combination of science and commerce as Paris vanishes in the luminous apotheosis of the sun. The fin-de-siècle intellectual works from and with a very particular conception of space, one that embraces the whole that is somehow dis-

connected from the parts. The juxtapositions of synecdoche give way to the displacements and transference of metaphor.

The intellectual whose engagement in the body politic so marks the late nineteenth century differs from earlier types of "public writers" on a number of dimensions.[20] Zola in the 1890s confronted an array of literary institutions more numerous and more complexly stratified than those with which Hugo had contended only twenty or thirty years previously. Political institutions too altered. The most vocal and most dramatic opposition to the Second Empire had come from dissidents outside the political sphere, and, for Hugo and others in exile, from outside of France altogether. By contrast, once the serious crises of the 1870s settled, opposition in the Third Republic played out almost entirely within the established rules of the game. Zola was denied the distance that allowed Hugo the implied mastery and omniscience of a bird's-eye view of politics.

What is notable about Zola's writing during the Dreyfus affair is the dissociation of his eminently political act from a particular time and from a particular space. In Paris those with the greatest attachment to the actual city are, paradoxically, the anarchists who seek with their bombs to obliterate specific signs of history and symbols of contemporary society. Guillaume finally chooses to dynamite Sacré-Coeur because it symbolizes the old society, the unenlightened world, the obscurantism of the church, and also the repression of revolution.[21] Against Guillaume's obsession with this church and the anarchists' fixation on topography, Zola sets out the ahistorical visions of Paris that punctuate the novel. Only when he has renounced the project to blow up the basilica is Guillaume able to see the ecstatic vision of the future harvest. Here is the real explosion of truth. The potential destruction of Guillaume's invention turns to construction of a new world.

When Zola invokes the Revolution in his articles on the Dreyfus affair, it is as a set of eternal principles. With the exception of the anarchists, revolution has lost its connection to Paris, to the city whose stones bear witness to this seismic event. Revolution becomes a function of overriding principles and metaphors of illumination. "J'accuse," Zola specifies, "is only a revolutionary means to hasten the explosion of truth and justice. . . . I have only one passion, that of light, in the name of humanity which has suffered so much and which has a right to happiness" (124). Precisely these terms abound in Paris,

which similarly divests "revolutionary" of any specific political content. Rather, Zola associates the legacy of the Revolution with an idea of France. His declaration to the jury during his first trial in February 1898 speaks to and for the nation: "We have to know if France is still the France of the rights of man, the France that gave liberty to the world and should give it justice. Are we still the noblest, the most fraternal, the most generous of peoples?" (132). "I have on my side solely the idea, an ideal of truth and justice" (134), he declares, echoing the many declarations of Paris. In the "Impressions d'audience," written during his first trial, he exhorts France to fulfill its promise. "To stay at the front of nations, to be the nation that will hasten the future, we must henceforth be the soldiers of the idea, the combatants of truth and right. Our people must be the most free and the most reasonable. It must fulfill at the earliest possible moment the model society, the one that is being born in the decomposition of the old society that is crumbling" (246).

The Dreyfus affair "is small indeed,. . . far from the terrifying questions that it has raised" (132). It is no longer a question of a man's fate but of "the salvation of the nation" (132). "The innocent man who suffered on Devil's Island was only the accident, a whole people suffered with him. . . . In saving him, we were saving all the oppressed" (204). France itself fades into the background before the vision of a transfigured society of supranational proportions that, once again, recalls the final scene of Paris. Accordingly, although Guillaume Froment originally plans to give his invention to his country to enable France to win the inevitable war with Germany, he eventually puts it at the disposal of humanity (reasoning that if every country possesses ultimate destructive potential, none will dare to use it). He will derive no personal gain from his invention, which he leaves for others to market. In an article written from his exile in England, Zola too insists that he has no desire to take personal profit from his action (152). In the disinterested intellectual, Zola reiterates again and again, lies all hope for the future. "Intellectuals [savants ] tomorrow, the hope for more truth and more justice; . . . Who does not feel that we are heading toward this truth, and to this justice, and who would dare to not side with this hope of work, of peace, of intelligence that is finally mistress of universal happiness?" (246).

In the Dreyfus affair Zola had only to follow the logic of his own metaphorical constructions, a "sower" of light and truth, who, like

his fictional characters, cultivates the future harvest of truth and justice. To the ideal that he propounds Zola adds a very distinctive ingredient, an element that is often lost in the campaigns of intellectuals in the twentieth century. Intelligence and reason do not suffice. Love is also essential. And it is not a universal love for all mankind, but the love generated in the family and focused on the individual, and especially the individual child. This is the sense of Pierre's marriage and the final scene in Paris that unites the family of scientists around the infant as well as the motor—both creations, infant and engine, equally necessary for the new society and the new century. The love embodied in the one is the necessary counterpart to the intelligence that materializes in the other.

Such is also the signification of Zola's claim at the very end of "J'accuse" to speak "in the name of humanity which has suffered so much and which has a right to happiness" (124). He speaks of humanity but through and for an individual. Zola's unequivocal condemnation of the Communards in La Débâcle and the anarchists in Paris originates in just this indifference to the human element. His ideal intellectual is moved by compassion as well as reason. Otherwise, woe to humanity. In the single usage of "intellectual" as a substantive in Paris, Zola denounces the "cold intellectual" who fails to temper intellect with understanding and sets a bomb that kills three people. This young man, an erstwhile student, does not resemble any of the other anarchists in the novel. Within the economy of the novel, his execution is not only inevitable but appropriate. For there is

no excuse for his abominable act, no political passion, no humanitarian lunacy, not even the exasperated suffering of the poor. He was the pure destroyer, the theoretician of destruction, the energetic and cold intellectual who put all the effort of his intelligence in justifying murder . . . And a poet as well, a visionary, but the most horrifying, . . . (581)

Only by renouncing his delusion of absolute justice can Guillaume Froment become the complete intellectual, just as Pierre must resolve his spiritual crisis by abjuring his passionate desire for absolute belief. "Did not his torment come from the absolute. . .?" (378). The absolute, whatever the domain, is deeply asocial, whereas the intellectual, for Zola, is profoundly social, deeply committed to humanity and to individuals even as Zola himself serves the idea of justice and the case of Alfred Dreyfus. The Parisian field and its abundant harvest

join the opposites in a vision of what human effort can accomplish. This vision of a new golden age is Zola's legacy of Paris to the twentieth century.

IV

Bergère ô tour Eiffel le troupeau des ponts bêle ce matin

Apollinaire, "Zone"

Shepherdess oh Eiffel Tower the flock of bridges is bleating this morning

If the representative figure of this new Paris and the new age foretold is the intellectual, assuredly the exemplary monument is the Eiffel Tower. As the fall of the Vendôme Column sealed the end of romantic Paris, so the Eiffel Tower proclaimed the modern Paris that faced the twentieth century. So familiar has the tower become, so inconceivable is Paris without it, that we forget not only how singular a structure it was in 1889 but also, over a hundred years later, how unique it still is. It has the simplicity of the triangle, a spire reminiscent of a cathedral, and intricate iron tracing that makes ascent an experience of a moving collage. There exists no other structure like it. Because the tower is sui generis, it is instantly recognizable as the emblem of modern Paris. Like the ideal of the intellectual in fin-desiècle France, the Eiffel Tower claims our attention without reference to its particular site, a detachment that makes the association with the city as a whole all the easier, all the more "natural." There is no necessary connection between the tower and the Champ-de-Mars. Its singular form would set the tower apart whatever the site. And, unlike the Vendôme Column, unlike monuments generally, the Eiffel Tower neither commemorates an event nor honors an individual. It appeals to no cultural memory other than those that it has itself created. Nor, whatever uses are made of it (telegraph, radio, and now television station, restaurants, historical exhibits) does it serve a purpose other than representational. Even the shops in the tower sell the tower itself, in what seems to be an infinite number of forms.[*] The Eiffel Tower

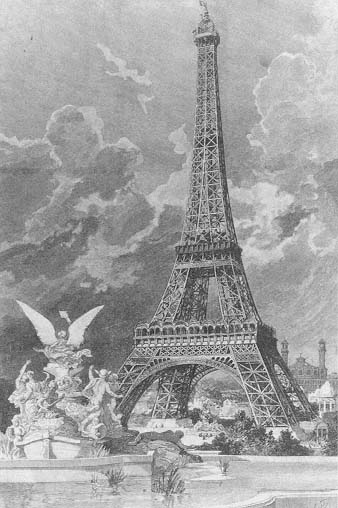

Plate 20.

The Eiffel Tower at the World's Fair of 1889. As the fall of the Vendôme

Column sealed the end of romantic Paris, so the Eiffel Tower proclaimed a new

and aggressively modern Paris. Built for the World's Fair of 1889 and for the

celebration of the centennial of the French Revolution, the Eiffel Tower resolutely

faced the twentieth century. The allegorical statues of Progress in the left

foreground, all curves, wings, and drapery, throw the stark, geometric lines of

the tower into even sharper relief. The classical allegory dwindles before the

very different grace and power of the modern representation as the clouds of

change hover on the horizon. (Photograph from the Bibliothèque Nationale,

courtesy of Giraudon / Art Resource, N.Y.)

is, as Roland Barthes observes in a marvelous essay, a "pure sign," open to interpretation by every user.[22] Viewing in this context is, of course, using.

Representing only itself, the Eiffel Tower is the indisputable synecdoche for modern Paris, ostensibly above the history that ties Paris to its past and, for that very reason, resolutely open to the future. So too Zola's Paris, with its metaphorization of the cityscape into a landscape, turns the city away from its site, its past, and its history toward a vision of future grandeur that will, by implication, eclipse the present as well as the past. Apollinaire's celebrated shepherdess tending her bleating flock of automobiles on the bridges of Paris magnifies by modernizing Zola's version of urban pastoral.

Although the Third Republic put the Vendôme Column back in place, it looked elsewhere to fix the imagination of the city and the country. The column was henceforth only one of the many monuments to dot the Parisian landscape—the landscape that the Eiffel Tower defined. The Vendôme Column, like all the other monuments and buildings that harked back to one or another ancien régime, proclaimed its connections to a past, even to several pasts. It made sense only in relation to the past, however dimly perceived or, for that matter, misperceived. To the contrary, the Eiffel Tower visibly had no ties to any past. It fit within no tradition. It was truly one of a kind. The deliberate absence of manifest historical reference opened the tower to every future, and does so still today. In a city where history so obviously marked virtually every corner, the Eiffel Tower was indeed, as it was accused of being, "foreign," indisputably not Parisian, not French. Its manifest ahistoricity challenged history itself and provoked very vocal protests like the manifest signed in 1887 by writers, artists, and other "passionate amateurs of the beauty of Paris" who spoke "in the name of French art and history" against "the useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower" then in the process of construction "right in the heart of our capital."[23] Its size alone—at 984 feet it is almost seven times the height of the Vendôme Column—meant that it could be neither ignored nor avoided.

Yet, as Haussmann's Paris had become nineteenth-century Paris, so the Eiffel Tower created its own space and its own history to become synonymous with the twentieth-century city. Now all comers could master the city from above. No longer was the bird's-eye view restricted to the powerful or the imaginative. The tower became quin-

tessentially Parisian. By the time of its fortieth anniversary, in 1929, a poll on whether or not it should be torn down found few advocates of demolition. The painter Robert Delaunay, for whom the tower was a favorite subject, even went so far as to call the tower "one of the marvels of the world."[24]

That the Eiffel Tower presents itself as resolutely modern and aggressively ahistorical does not, of course, place it outside history. The very ahistoricity of this extraordinary structure fits rather neatly within the larger political project of the Third Republic. To forge a national consensus and to stabilize the country, the republican governments after 1871 slowly but surely de-revolutionized the Revolution. It took over a decade of often bitter political debate punctuated by constitutional crises for the regime to settle into the patterns that would make it the longest French government after the Revolution (18701940, a record that will hold for many years to come).

Not the least of these battles concerned the emblems through which the republic exemplified itself to France and to the world. A symbol system had to be reconstructed. The Third Republic worked diligently to build a republic that would accommodate the past with the future, a republic whose glory would draw upon Louis XIV and Versailles as well as Napoléon and the Civil Code and even the fall of the Bastille. A series of key dates charts this delicate process of ideological negotiation as the republic went about selecting its ancestors and overhauling its symbolic arsenal: 1878, the centennial celebrations of the deaths of Rousseau and Voltaire, the twin deities converted to republican duty; 1879, the vote for "La Marseillaise" as the national anthem; 1880, declaration of 14 July as the national holiday; 1885, the gigantic state funeral of Victor Hugo, the ecumenical republican par excellence; and finally, 1889, the joint celebration of the centenary of the Revolution and the World's Fair. Inaugurated in 1889 the Eiffel Tower thus participated in both the revolutionary celebration and the celebration of scientific and technological progress. Even though the organizers of the centennial most certainly bore in mind the revolutionary festivals held there, it was with the intention of rewriting revolutionary history. The Champ-de-Mars was to be the site of a festival for a new revolution. On the erstwhile military parade ground, the revolution of science and commerce made its claims. The Eiffel Tower signaled the determination of the republic to face res-

olutely forward. It would take from the past only that which could be turned to account for the France of tomorrow.[25]

Because the violence of revolution had no place in the new France, the Paris explained by the Revolution had to be redefined, reconstructed, and reimagined. Bastille Day became the national holiday, but the animation was confined to commemorating not reenergizing the Revolution. No single image of Paris at the end of the century carries the powerful charge of revolutionary Paris. The myth had lost its force.[26] The Eiffel Tower could remain the emblematic urban icon because, figuring none of them, it could signify them all. It was in a sense the "degree zero" of the city.

<><><><><><><><><><><><>

The hold of the Revolution of 1789 on the collective imagination of France and Europe throughout the nineteenth century lay in its proleptic powers. The Bastille and the guillotine, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the execution of the king, cast a long shadow forward, inviting, even requiring that the present be understood through a certain past. The future, as well, was a function of that past, one in which order and turmoil cohered. The French Revolution of 1789 substituted prophecy for teleology, a vision that gained strength from the ensuing revolutions that occurred with distressing (or exhilarating) regularity in the decades that followed the siege of the Bastille.

Paris as Revolution has claimed that nineteenth-century re-visions of Paris, and especially the myth of Paris that structured so much writing about the city, depended upon a concerted need to create and, thereby, fix and place through the language and symbols at hand. Like any other interpretation that proposes an order, these reconfigurations of Paris arrested change, the better to determine its course. Haussmann's willful transformation of Paris illustrates to perfection how "rewriting" the cityscape redirected and then determined new imaginative practices of the city.

The texts that produced the mythic city of Paris depended on a distinct nineteenth-century sense of the whole. Paris stood for something complete and, above all, knowable. Accordingly, when writers no longer felt the desire, the will, or the imaginative capacity to grasp the city as a whole, the myth of revolutionary Paris lost both imagi-

native force and literary significance. The traditional metaphors, the conventional metonymies, and the standard synecdoches no longer conveyed the complexity of the modern city; their power to define space and to determine place diminished rapidly. By the end of the century, the holistic metaphor of revolution that had guided so much thinking about the city had run its course. It was, after all, a profoundly disquieting metaphor. It channeled change, to be sure, but it did so with the promise, or the warning, of still more change to come, more movement, more mobility, more confusion, and, of course, more bloodshed. Revolution proposed change as the norm, as the fundamental category of social existence. In the end, revolution as metaphor necessarily came into conflict with the Revolution as the primal, founding event of modern French society. This historical revolution was still a catalyst, but it came increasingly out of a fixed and determined past.

There was never a scarcity of competing definitions in the nineteenth century. The conception of revolution proved extraordinarily capacious. That one talks about an "Industrial Revolution" in spite of egregious dissimilarities from the political events of the same period points both to the versatility of revolution as an abstraction and also to the need to make sense of change in terms of a comprehensive sign or emblem. Belief in revolution meant acceptance of change as a way of life and mode of perception. It would be no wonder, then, that the fin-de-siècle, quite apart from the cultural colorations that it took on in particular settings, turned toward an interrogation of time in its own search for meaning.

The myth of Paris that unfolded over the nineteenth century developed out of this perception of temporal and spatial mobility and from a concomitant urgency to check that movement. Moreover, the historical novel at its most serious and most modern—from Scott and Balzac to Flaubert and Zola—exemplifies exactly this conflation, one in which chronology and topography combine. The two, a myth of urban history and the historical novel, join in the chronotope of revolutionary Paris, the topos that infuses urban space with recognizable movements in history. The same conjunction is fundamental to making sense of the modern city, and in particular to an informed understanding of Paris as the paradigmatic city of modernity. The chronotope proves an apposite figure to the degree that it translates into textual terms the double vision that imposes time upon place

and the corresponding triple vision that brings past, present, and future together in a meaningful whole. The passion for being modern inheres in this perception of living in a place and a time that make sense on y when interpreted as a function of change, disruption, and transformation. It is, then, not by chance that the central novels in the nineteenth-century tradition produced a powerfully urban model of history. Nor is it an accident that so much of the debate over the novel as a genre should take place among French critics and about French novels, in which that model carries such intensity.

Much is made of the disruptive force of modernity and of the instability that, at least since Baudelaire, is taken as its essential feature. Analyzing and dramatizing both the social forces that produce the condition and the condition itself preoccupied writers and intellectuals of every persuasion throughout the century—from the "mal du siècle" diagnosed by Chateaubriand to the "bovaryisme" dramatized by Flaubert to the deracinement attacked by Barrès and the anomie diagnosed by Durkheim. Each interpretation, even as it accepted the universe of perpetual motion, offered meaning and stability of a sort, however illusory stasis inevitably turned out to be.

As one would expect, the exhaustion of revolution as an organizing scheme for conceptions of the city coincided with the advent of other models of interpretation. By the end of the century, urban narratives began to work through other elective affinities as literature engaged the city on other terms. Paris splintered into many cities, and revolutionary Paris dissolved into any number of images. The literature of the twentieth century moved elsewhere, and decisively inward. Writers took their inspiration from the many new cities and their myths—the idealized urban landscape of the Impressionists, the Gay Paree of cabarets, the intellectual's city of university and academies, the Paris of art studios and galleries and cafés that drew writers and artists from all over the world, and the greatest of the literary cities of the Belle Époque, the Paris of Proust filtered through the lens of memory. The Paris of the Eiffel Tower and the World's Fair of 1889 did not celebrate revolution but rather the centennial of 1789. The republican present sought to assimilate the turbulent insurrectionary tradition by removing it safely to an increasingly remote past.

Each of these new cities at the end of the century forged its own myths and lived off its own legends. But none of them depended, as before, on the totality of conception inherent in revolution. No mod-

ern author claimed the city as Balzac, Hugo and Flaubert, and Vallès and Zola once claimed it. The reconceptualization of the city brought new practices of urban space and new visions of revolution. The revolutionary tradition that Zola invoked so dramatically during the Dreyfus affair has no privileged space in the twentieth century. It is, rather, a sensibility, a consciousness, a set of abstract principles. The modern intellectual that Zola put into circulation does not write from or identify with a special place. No urban icon, no urban narrative can contain the principles of right and justice that guide the intellectual. Henceforth the intellectual who claims to speak for humanity does so disengaged from the particulars of time and place as a relatively disembodied figure.

For the century before, the interpretation of meaning meant Paris, and Paris arranged itself around revolution—revolution in its streets and revolution in its narratives. Making sense of the one always entailed making sense of the other. Indeed, the great works of this city and this time centered on that interaction and invariably reached for some larger form of integration. Over and over again, writers turned to place within a narrative of revolution to fix but also to convey the meaning of change in that movement. Paris was the subject; revolution, the inevitable theme.

By the end of the century, the virtuoso metaphor that served the urban imagination so long and so well served no longer. The cityscape disaggregated, and the bird's-eye view revealed not overall design but fragmentary scenes of almost unimaginable diversity. Zola's Paris made one final attempt to comprehend the city as a whole, but the knowledge came at a great price. This final Paris dissolved into a utopian vision of the future with little connection to the dynamic, revolutionary, and eminently visible cities of Hugo, Flaubert, Vallès, and even the young Zola. Like Zola in the articles on the Dreyfus affair, the intellectual of the twentieth century sees largely within the mind's eye.

Of course, Paris does not disappear from literature. On the contrary, in some senses the city is never more present. But, somewhere, early on, the twentieth century loses both the certainty that Paris can be known and the conviction that revolution holds the key to that knowledge. Writing the twentieth-century city implies different urban practices, entails very different strategies, and works with different symbols. Louis Aragon's marvelous Le Paysan de Paris (The Peasant of

Paris ) (1921 ), by way of example, takes on the city but in a decidedly surrealistic mode. Aragon works off the fragments of a public discourse (the signs and the advertisements in the Passage de l'Opéra, which he reproduces in loving detail), but he does not suppose any global coherence, much less one with revolutionary connotations.

The real coda to the myth of Paris comes with Raymond Queneau's Zazie dans le métro (1959). During the whirlwind Paris visit of Zazie, an inordinately precocious girl of eleven or twelve, even the most inveterate of her Parisian guides—a taxi driver—is never altogether sure whether he is looking at the Sacré-Coeur or the Invalides or the Panthéon (they all have domes), and there is always a sneaking suspicion that the building in question just might be the Gare de Lyon. Queneau's spoof of the modern guided tour to Paris also parodies the whole literary tradition of urban exploration. This Paris-Guide, or antiguide, for the twentieth century systematically effaces the historical and topographical differences crucial to the sense of history that informs the great urban narratives of the nineteenth century. At the same time, as parody, Zazie presupposes that history, that topography, and that tradition. The humor depends on the reader knowing that the monuments are from very different historical eras and are located in quite different parts of Paris. It also depends on catching the connections to Hugo's epic Les Misérables when Zazie is rescued from the police by her uncle's transvestite lover, who carries her through a sewer into the métro to the train station. For Hugo's christological Jean Valjean, who carries the wounded Marius through the sewers to his home in the city, Queneau gives us a complicated figure of uncertain meaning who takes Zazie out of, not into, the city.