IV

L'habit ne fait pas le moine.

French proverb

For the apparel oft proclaims the man. Hamlet (I, iii, 72)

The success of the new Paris, the exploits of Saccard and the society that he keeps in constant turmoil, are condensed during Renée's last promenade in the Bois de Boulogne in Saccard's cry of "Vive l'empereur!" as Napoléon III passes in "a triumphal parade" (336). That triumph has its costs in the maladies that are on public view. The sickness of the emperor, seen twice, each time weaker, is the obvious

exteriorization of the illness that will bring down the regime. The emperor who ages noticeably over the two years of La Curée will turn into the totally bewildered old man facing certain defeat at the hands of the Prussians whom Zola portrays in La Débâcle (1892). But Renee's own disease, her vice, and her crime center the novel. If the emperor manifests the sickness that saps the Second Empire, Renee brings that disease to the city itself. Her beautiful shoulders are twice characterized as the pillars on which the empire rests: "Admit outright," Maxime tells her, "that you are one of the pillars of the Second Empire" (45, cf. 205). Her malady and her fever will be its malady and its fever. But the same scene immediately ties Renée to the city. Those bared shoulders and décolletage so impress the public officials in attendance at the ball that Eugène Rougon knows he will have little trouble the next day voting another loan for the city.

With Renée, Zola elaborates two familiar images of Paris: the city as woman (and particularly as courtesan) and the city as the head, le cerveau, l'intelligence, la tête du monde. From the beginning to the end of the novel Renee is characterized as an intelligence gone awry. Her nervous disposition will easily turn into madness. And so it does. "La folie" becomes an ever more frequent notation as the novel progresses. This insanity implicates the city as a whole: "Maxime himself was beginning to be frightened by this head where madness was spreading, and where he thought he could hear at night, on the pillow, all the uproar of the city lusting after pleasure" (241).[18] When, predictably, Renée dies, her illness is acute meningitis—that is, brain fever, which once again stands for the madness of the city itself: "In the feverish sleep of Paris, one could sense the breakdown of the brain, the golden and voluptuous nightmare of a city crazed by gold and flesh" (163). Paris realizes the predictions of Saccard, "pure madness, the infernal gallop of millions, Paris intoxicated and knocked out flat" (114).

This is the Paris of the hunt, and more precisely of la curée, that is, the most dramatic moment in the very public spectacle of the hunt. Although the figurative sense of his title dominates (the race for political spoils), its literal meaning invariably brings the original sense of the hunt into play. Zola takes care to specify that the wedding of Aristide and Renée occurs at a time when "the passionate rush for spoils [la curée ] filled a corner of the forest with the yelping of the hounds, the cracking of the whips, the flaming of the torches" (162).

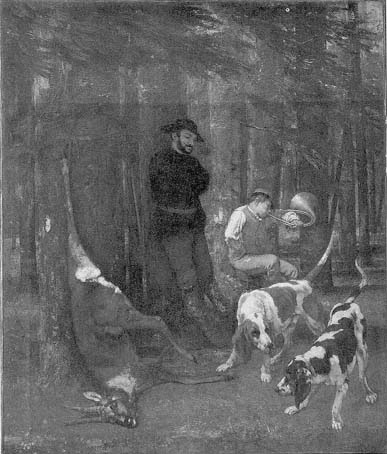

Plate 13.

La Curée by Gustave Courbet (1856). The hunt was a favorite

subject for Courbet. Here the painter focuses on the final moment, when

the entrails of the quarry are to be thrown to the hounds. The hunter

leaning against the tree is curiously detached from the death he has caused,

quite as Aristide Saccard in Zola's novel La Curée dissociates himself

from his wife's descent into madness and eventual death even though

he too has loosed the hounds on the victim. The painting would have

been familiar to many readers through the lithographic reproduction that

appeared in the literary review L'Artiste. (Photograph courtesy of the

Henry Lillie Pierce Fund, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

The hunt provides both a general image for the novel and one specific to Renee. The associations with animality throughout the novel—her hair, the fur and velvet skating outfit, the bearskins on which she and Maxime make love, the fur wrap with which she covers herself at the ball, and especially the dress embroidered with all the motifs of a deer hunt—turn her into the quarry (la curée ) in the original sense of the term, the part of the animal fed to the hounds that have run it to the ground.[19] The image would have been familiar to contemporaries from Courbet's painting of La Curée, exhibited in the Salon of 1857 and reproduced in a lithograph in L'Artiste the following year.[20] When Renée finally "sees" herself naked, she understands that she is trapped and that Saccard has directed the hunt from the beginning, putting out his traps "with the refinements of a hunter who prides himself on capturing his prey with style" (251). One might further connect Courbet's strangely passive and detached pipe-smoking hunter-artist and the piping huntsman to Saccard and Maxime strolling in the Bois de Boulogne at the end of the novel, puffing on their cigars, altogether as indifferent to Renée's plight as Courbet's huntsmen are to the dead roebuck hanging in the opposite corner of the painting.

Saccard has despoiled Renée of her entire fortune and thrown her to the hounds just as he has attacked Paris. In a key scene early in the novel, Saccard surveys the city from the heights of Montmartre, and "with his outstretched hand, open and sharp like a cutlass," he sketches in the air the projected transformations of the city (13). Saccard later recalls his prediction with great satisfaction: "There lay his fortune, in those famous slashes that his hand had made in the heart of Paris . . . a slash here, then on this side, another slash, a third slash in this direction, another in that . . . slashes everywhere" (1314)—all in all a very apt description of Saccard's calculated attack on Renee. His was not the original rape of Renee, and his was not the idea for the transformation of Paris. It was the emperor who traced the original plan on the city map. When Saccard surreptitiously consults the famous map marked up by the emperor for the prefect, he sees that "these bloody lines of a pen slashed Paris even more deeply" than had his own hand (1 16). But Saccard, not Haussmann, is everywhere at once. Saccard rushes in the same day from the construction site of the Arc de Triomphe to that of the boulevard Saint-Michel, from the excavations on the boulevard Malesherbes to

the embankment work at Chaillot. "The central city was being slashed all over, and [Saccard] had a hand in all the slashes, in all the wounds" (142). The Crédit Viticole founded by Saccard—his "purest glory" (143)—"held the City of Paris by the throat" (276).

The clear connection between Renée and Paris, the responsibility that Saccard bears for Renée's debasement, his parallel responsibility for the "disemboweling" of Paris, would seem to constitute an unequivocal condemnation of Saccard and by extension of Haussmann and his great works. But the novel is nowhere nearly that simple. If Renee dies, Paris lives on in the Third Republic from which Zola writes, having recovered from its "fever," its "wounds" having healed. What then of the denunciation of la curée and of the transformations of the city that let loose the hounds? The contradiction is only apparent. Renée is not a Balzacian metaphor of the city as woman, but an exemplum of a very particular society. The associations Zola establishes with Paris are with a Paris that disappears, the Paris of the Second Empire, which dies along with, if somewhat later than, Renée. The moment of la curée, we must remember, signals the end of the hunt.

Renée is, for that matter, rather too obviously the incarnation of that society. Her sickness—"her sick heart" (47), her "morbid air" (49), her "madness" (56)—does not end the novel but begins it, and the explicit association that Renée herself makes with Phèdre brings to mind Racine's opening description of his heroine, "a dying woman seeking death" ("une femme mourante, et qui cherche à mourir"). Renee's other associations are with the artificial. At one point she is likened to "an adorable and astonishing machine that is breaking down" (247). At several other instances her image is of a statue, a she poses at Worms' studio (139), in the tableaux vivants at the costume ball, and elsewhere (206, 270, 308). Similarly the connection with dolls. In the mirror she sees a "strange woman in pink silk . . . who] seemed made for the love affairs of marionettes and dolls. She had come to this, a big doll whose torn chest only lets out a stream of sawdust" (311); and when she finds one of her old dolls in the attic of the Hôtel Béraud, the body limp from all the lost sawdust, the painted head still smiling, she bursts into sobs.

Paradoxically, Renée is most fully herself as the nymph Echo in the tableaux vivants staged during an evening at the Hôtel Saccard. For she is the Echo of the Second Empire. Her unsatisfied desires are

those of all the other characters; in her malady resonates the madness of the Second Empire. As Echo she acts out her desire for Maxime-Narcissus. Rejected by Narcissus as she will be by Maxime, Renee stages her own death. Powdered from head to toe, as one of the spectators rather maliciously observes, she looks dead. The insatiable desires of the Second Empire will lead to its downfall as Renée's ever greater desires will lead to her death. Understandably, the audience does not much like the final tableau, which depicts the deaths of Echo and Narcissus. Although the audience cannot appreciate the complexities of the allegory, the identification with the wealth in the earlier tableau has been too strong for them not to reject the depressing denouement.

This "textuality" sets Renee apart and makes her a product of this society rather than of a Paris for all time. Renee's texts are, indisputably, her dresses, her "rags" ("chiffons"), as Saccard calls them (17). The continually changing outfits that astound all Paris situate Renée within the same economy of mobility and ephemera that governs Saccard. Moreover, the debts that she accumulates for the clothes that allow the perpetual transformations of self, the vast sums that she owes the great designer Worms, offer an exact parallel of the debts incurred by the city for its continual transformations. In both cases the solid bourgeoisie pays: Renee's father, not her husband, pays Worms' bill of 257,000 francs just as the run of ordinary citizens ultimately will finance the loans floated by the city.

Beyond the overwhelming extravagance that they proclaim, the individual outfits are virtually the only manifestation of Renee as an individual, which is also her definition by society. Clothes, in this instance, express and make the woman. Just as Saccard would not exist without his masses of papers, so too Renee has no social existence apart from her closets full of "rags." Hence the burden borne in the novel by the particular ensembles. What distinguishes Zola's descriptions from the fashion reporting on which he drew for these descriptions is, paradoxically perhaps, their significance. These clothes signify Renée, and beyond Renée they signify the Second Empire. The two most striking examples are the costumes that Renee wears for the tableaux vivants—an allegory within the larger allegory of the performance: "The nymph Echo's dress was a complete allegory all by itself" (280) and the ball dress, "that famous satin dress the color of bushes on which a complete deer hunt was embroidered, with all its features,

powder horns, hunting horns, broad blade knives" (226). Her very dress identifies Renée as the quarry, la curée.

The factitiousness of Renée's wardrobe that marks her as uniquely a product of society contrasts with the garb of the Seine. The river not the woman wears the most beautiful dress in the novel, a dress that owes nothing to Worms (but everything to Zola): "The Seine had put on its beautiful dress of green silk flecked with white flames; and the currents where the water eddied added satin ruffs to the dress, while in the distance, beyond the belt made by the bridges, streaks of lights spread out panels of material the color of the sun" (338). The "changing dresses" of the Seine "went from blue to green, with a thousand hues of infinite delicacy" and from afar resembled "the enchanted gauze of a fairy's tunic" (128). The view from the turret of the Hôtel Béraud reveals a Paris outside fashion and outside history, a mythic Paris whose "soul" is the Seine, "the living river" that flows "in tranquil majesty" (128). As a young girl Renée easily tires of this immense horizon; as a woman, sick unto death, she comes too late to prize this "old friend" (338), this Paris far from the frenetic new Paris of the boulevards and the Bois de Boulogne. Unlike Renée, caught in the maelstrom of a particular historical period whose movement she is unable to discern (her myopia is telling in this regard), this eternal Paris, nourished by the Seine, will recover from the "fevers" of the Second Empire.