Street Figures

Victorian Urban Iconography

Richard L. Stein

Spell Checks

"Give me," said Joe, "a good book, or a good newspaper, and sit me down afore a good fire, and I ask no better. Lord!" he continued, after rubbing his knees a little, "when you do come to a J and a O, and says you, 'Here, at last, is a J-O, Joe,' how interesting reading is!"

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

I begin with the question this essay is designed to answer: how do we read cities? Of course, an attentive reader may wish to object. Which cities? Why read? Who is "we"? In fact, those questions are buried in the original one; I will suggest some ways they can be exhumed, and applied to some nineteenth-century texts. Before doing so, I want to stress that the same issues underlie contemporary urbanology, if I can use a fancy word for a commonplace activity. How often do we explain that "I'm a city person," or boast of our "city smarts"? It is not only New Yorkers who refer to home base as The City, to suggest not merely that there can be no other but that all others must be understood in terms of that Neoplatonic model—to which few measure up. If there is a city "look," is there not also a city looking, a glance by which one urbanite surveys, acknowledges, and then promptly ignores another? Even if there is not, do we not (like Bloom in the butcher's shop) imagine there is? Populated cities populate our consciousness, and our self-consciousness. The very habit of generalizing urban experience, our urban experience, is one of the ways "we" define identity in a culture preoccupied by the erosion of self in mass society. Perhaps the question

should have been, not how, but why do we read cities? If so, one answer could be that we read them to show that we still can read—that is, that we can read—that there are still "we's" to do the reading.

But there still may be objections to that last word: why reading? One answer has to do with the rise of discursiveness in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and more specifically with the concurrent interrelation of increasing literacy and increasing urbanization, the former skill increasingly necessary for the latter process and increasingly implicated in the growing complexity of life it involves. Remember Nicholas Nickleby surveying help-wanted placards at the General Agency Office; as any member of the MLA can attest, even job searching requires special tactics. Henry Mayhew begins London Labour and the London Poor with a quasi-anthropological account of his subjects as the last descendants of primitive nomadic tribes. But his four volumes of dense prose and statistics suggest that they could just as easily be characterized as hunters and gatherers of information, not unlike himself. The urban process makes data processors of us all. The city demands special skills, including the mastery of specialized languages. In Dickens's first urban novel, Oliver Twist makes this discovery at the city limits when he encounters the Artful Dodger and his "flash" vocabulary. Every successful Dickensian hero learns a similar lesson—not mastering the language of the streets but mastering the streets like a language, and mastering language as part of the education that guarantees increased mobility through and within the city. This explains one connection between Pip's education and his oarsmanship, tokens of his increasingly swift progress across the urban map. It helps explain another distinction between his literate mobility and the rootedness of Joe Gargery, who comes up to London only on urgent missions, and whose incapacity for such adventure is signaled early by his rough, simplistic progress among lexical landmarks. For Joe, reading is an exercise in deciphering print to yield up letters, searching for crude versions of his own name and in the process reducing it from three letters to two. Pip in London expands himself and his prospects, acquiring a new "Handel" (the name bestowed by his cultured friend, Herbert Pocket) that carries him beyond the palindromic circularity of his own first reading of himself. He gains a more complex verbal identity—a six-letter name that like narration links different "characters," one requiring an ability to reimagine the self through witty allusion and familiarity with the civilized arts.

But not without a struggle. As the irony of the Dickensian title forewarns us, the balloon of hope must be punctured, and just as Pip seems prepared to rise with it high above his past. The vertical-spatial meta-

phor is very much a part of the rising and falling action of the novel, especially in the telling chapter when Pip's expectations reach the end of what Dickens calls their second "stage" and he hears a "footstep on the stair" leading up to his chambers. In the figure of Magwitch, Pip confronts his lowly origins and the chief figure of his nightmares, an image of his past and a dimension of an identity he had struggled to escape. But this return of the repressed is also an encounter with someone we could call, more simply, a figure from the streets, one whose power of impressing himself on the imagination derives to some degree from his being simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar, known and unknown, a fragment of childhood memory now merged with the urban uncanny. As he first surveys his benefactor in this second encounter, Pip can only describe him in relation to recognizable types, what George Cruikshank called in a volume of drawings "London Characters." The description focuses on general impressions, skin color and clothes, the stuff of caricature. "Moving the lamp as the man moved, I made out that he was substantially dressed, but roughly; like a voyager by sea." Later, as Magwitch sleeps, Pip wonders whether, or how often, he had encountered him before: "I began either to imagine or recall that I had had mysterious warnings of this man's approach. That, for weeks gone by, I had passed faces in the streets which I had thought like his. That, these likenesses had grown more numerous, as he, coming over the sea, had drawn nearer."[1] This Nabokovian linkage of memory and hallucination also suggests the necessary mechanisms of Pip's recently urbanized gaze—the instinctive resort to stereotypes, the compulsive creation of distance. The clue to the process resides in those odd verb tenses. How could it have been possible, in the few weeks before he reencountered Magwitch, for Pip to have "passed faces in the streets" which he "had thought like his"? Not insofar as Pip was explicitly recalling the memory of this or any particular man. Rather, because the likeness he remarks on here is generalized. Meeting Magwitch in his chambers, Pip sees not an individual but a type, a type of the same sort one sees—or thinks one sees—in sizing up the random figures encountered in the daily hustle of urban life. City seeing always requires a quick and comprehensive transformation of people into Others, into forms that are simultaneously more recognizable and more anonymous than they might have been otherwise, into what Pip calls "faces in the streets." What Pip remembers seeing is himself not seeing, not seeing in response to the seen unseeable quality of the figures who surround us in the density of city streets. And how can we see clearly, in an individuated way, when doing so only defines our proximity to those others, only suggests that as ur-

banites we are street figures too? Random faces, random names—persons impersonal, like figures of speech—whiches (as Joe Gargery might say), in every sense (and spelling) of the word. At the crisis of his expectations—and this is what makes it a crisis—one of these figures climbs out of anonymity and threatens to reclaim Pip, not merely for the past and his own repressed memories, but for the streets he thought he had kept at a distance.

Invisible Cities

"To carry out an idea[!]" repeated Miss La Creevy; "and that's the great convenience of living in a thoroughfare like the Strand. When I want a nose or an eye for any particular sitter, I have only to look out the window and wait till I get one."

Charles Dickens, Nicholas Nickleby

Perhaps nothing seems more natural than to speak of Dickens and cityscaping, or to do so in relation to what this volume calls the Victorian visual imagination. Few writers are so strongly associated with descriptive, graphic detail—or with that special urbanographic form we think of as Dickensian London. But what about Nicholas Nickleby? It is nearly a critical cliché to observe that this is not an urban novel, even though the main action takes place in and around London. It is not really a novel of place, either; aside from the large shifts of location to Yorkshire and Portsmouth, there is little temptation to "plot" the action against a map. For that matter, and in spite of Michael Steig's study Dickens and Phiz,[2] I would argue that in the Dickensian corpus this does not qualify as a particularly graphic novel: it is not a source of famous descriptive set pieces, nor is it organized around either decisive moments of pictorial drama (like the mob scenes in Oliver Twist or Barnaby Rudge or A Tale of Two Cities ) or idylls of reconciliation (as in Bleak House or David Copperfield ). But the main point I want to emphasize is that these two qualities, these two lacks, are related. The relative invisibility of London in the novel is both cause and effect of its avoidance of a range of pictorial effects Dickens employed more extensively in other works produced at roughly the same time. It is not simply that the easiest means of suppressing London is suppressing the visual, or vice versa. The motives for that mutual suppression are linked in turn to the conception of Nicholas Nickleby as book and as character—to the

conception of Nicholas (if I can use this term) as an action, as a career, as a role.

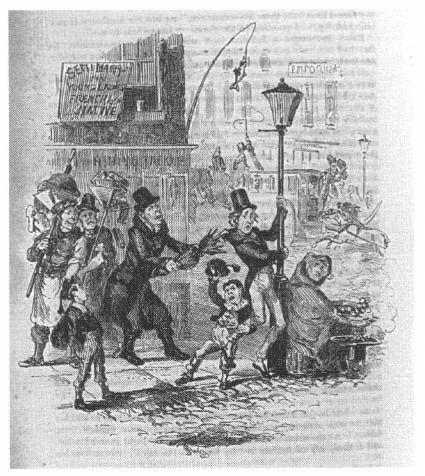

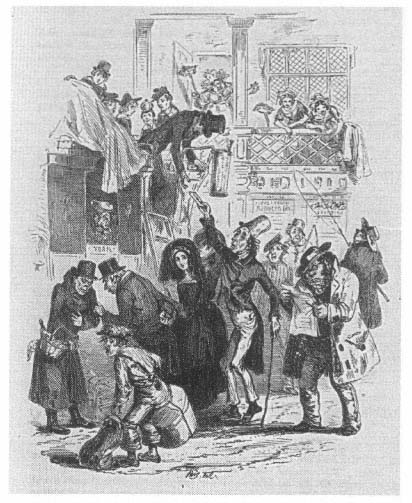

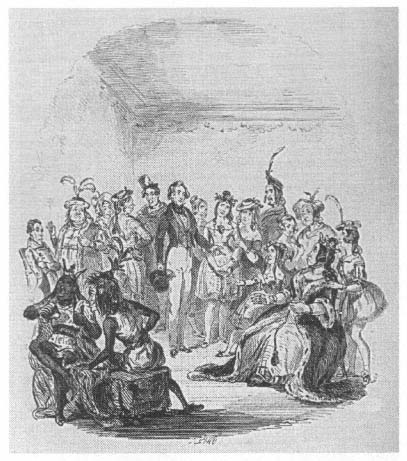

To suggest what I have in mind, I turn to illustrations, always a sensitive register of the ways Dickens engages the contemporary visual imagination. I take that engagement for granted: rather than discuss the inevitably complex relation of image and text, I want to suggest something about the relation of both to the densely visual world of the city, and the relation of that density to Victorian conceptions of self. Consider two representations of the sort of urban scene we associate with many Dickens novels: George Cruikshank's drawing of "Oliver claimed by his Affectionate Friends," and Phiz's illustration, for Nicholas Nickleby, of "A sudden Recognition, unexpected on both Sides" (Fig. 70). There are clear parallels between the illustrations and the situations to which they refer. In these early novels, as later in Great Expectations, London stands for potential abductions; the jumble and confusion of the streets threatens to reclaim us from the hard-won security of domestic shelter—to take hold of us, to bring us down, or (to use a metaphor chosen with Magwitch in mind) to reach out its hands. In Nickleby, it is Smike who is most susceptible to this threat. Our hero—and this is one of the ways in which he fills that role—remains above and apart from the crowd, mediated for him figures like Newman Noggs, a "fallen" gentleman who by virtue of his descent can mingle with the heterogeneous confusion of the urban mass. To some extent that is Noggs's job; to some extent, it is a fate he has embraced, a vantage point from which he can extend a helping hand to his venerable, vulnerable friend. Phiz illustrates the relation in the scene where "Nicholas starts for Yorkshire" (Fig. 71), an image that in spite of its title really centers on Noggs. Nicholas here is bent and inert, his features nearly obscured, not so much in anticipation of his impending life at Dotheboys Hall as from the strained "position" he has been forced to occupy already in this first immersion in urban life. For him to fill the role of hero, a less chaotic setting is required, one represented by the structured paradigm of the theater, where under the grandiose tutelage of Vincent Crummles he learns to assume a "character" within a limited and highly conventionalized space. Two more illustrations delineate the distinction: "Nicholas Hints at the Probability of His Leaving the Company" (Fig. 72) and "Nicholas Congratulates Arthur Gride on His Wedding Morning." Both, in effect, place him onstage, for the private, domestic interior is as much a theatrical scene as the one set in a playhouse. Such images provide a literally graphic reminder that this is a novel concerned with the hero's position, the hero as position. What defines Nicholas as a character is less his

psyche than his role, his place in a stylized tableau of alternatives and possibilities.

I am arguing that Nickleby generally suppresses the urban setting and graphic technique we associate with other Dickens novels. The reason has to do with the character of the hero, with the risks he would incur if placed, or represented, in too direct or too prolonged contact with the physical realities of London life. Perhaps more than in any other Dickens novel, the city of Nickleby threatens the very possibility of character, a stable sense of self; it is a place where nothing is more difficult to establish or maintain than a secure identity, the ability to "position" oneself. The nature of the risk is suggested when Nicholas ventures into the streets to search for a "position" in the other sense of the word. He "mingle[s] with the crowd" on "one of the great public thoroughfares of London" as he wanders toward the General Agency Office. Dickens makes it clear that the journey would be dangerous for anyone less totally self-absorbed: "a man may lose a sense of his own importance when he is a mere unit among a busy throng, all utterly regardless of him."[3] But Nicholas can resist "speculating on the situation and prospects of the people who surrounded him," just as he can remain skeptical of the agency's promise to supply "places and situations of all kinds." It is precisely his suspicion of such claims that will finally get him a job, following conversation with another uneasy reader of the agency ads:

"A great many opportunities here, sir!" he said, half-smiling as he motioned towards the window.

"A great many people willing and anxious to be employed have seriously thought so very often, I dare say," replied the old man.

"Poor fellows, poor fellows!" (449)

What immediately bonds Nicholas and Charles Cheeryble is their common sympathy for such victims, which is also to say their common distance from the world that produces them. When Nicholas refers to the "wilderness of London," Charles vigorously approves the phrase. "'Wilderness! Yes it is, it is. Good! It is a wilderness,' said the old man with much animation." (450). Out of such fellowship Nicholas comes to find a position in but not of London—in the urban pastoral world of a "quiet, shady little square" (456) that for Tim Linkinwater offers a better view than any place in England. This is one of the rare urban settings in the novel that Dickens represents in detail, although his description (468–69) emphasizes the difference between this "desireable nook" and the rest of London. Yet even here, as on the Yorkshire coach, Nicholas is represented by Phiz with his face averted, as if he must com-

pulsively bury his nose in work. Even in this refuge one must exert an effort to keep the confusion of the city wholly at a distance, as Newman Noggs discovers when he tries to follow Madeline Bray's servant and ends up pursuing another instead. Lacking Nicholas's firm sense of self, or the anchoring force of habit suggested in Tim Linkinwater's name, he is lost in the urban maelstrom—a new man who can easily become no man, another casualty of the similarity of street figures and urban types.

The episode of the mistaken servant—we might call it the Bobster Bungle—suggests another important connection between the invisibility of London in this novel and the curious general avoidance of urban pictorial detail. For here, in exaggerated Cockney comedy, Dickens explores the perils of resemblance, and the uncertainties surrounding representation as such. I do not want to make too much of one mistake. Newman may have been simply inattentive, or drunk—confused by urban topography, urban motion, and that second servant. But these explanations remind us of the indistinguishability of street figures, the interchangeability of city lives. Cecilia Bobster parodically doubles for Madeline Bray: only child, mother dead, father a "ferocious Turk." In a sense, she suggests what Madeline might become outside the precarious shelter of her father's home, how easily she could be misrepresented, or mistaken—that is, taken for someone or something else. Even Noggs, who remembers Bobster by Lobster, in a sense dehumanizes her; certainly Gride would have treated her as a consumable delicacy. But Miss Bray herself, in her quasi-professional artistic enterprise, is producing consumer goods, practicing a commercial art. It is one more token of her desperate condition: replication of certain kinds seems suspect. As in the case of "the little miniature painter," it is an activity associated with the decline—or should I say reduction?—of art and the artist, representation too closely affiliated with the streets.

Perhaps, then, Mrs. Nickleby is not wholly foolish in attaching some sort of stigma to Miss La Creevy. The remarks I quoted as the epigraph to this section suggest the extent to which her portraits involve a dissolution of personage, a supposed representation of identity that in fact reconstitutes it from a collage of borrowed characteristics. As she explains to Kate, "What with bringing out eyes with all one's power, and keeping down noses with all one's force, and adding to heads, and taking away teeth altogether, you have no idea of the trouble one little miniature is" (114). What she calls "Character Portraits"—pictures that represent their subjects in a variety of fictitious roles—assume the total malleability of character, or its total lack of meaning, as if self were as

interchangeable as costume. No wonder her customers for this genre are "only clerks and that," urban nobodies who want to become urban somebodies, whose choice of roles is only between different grades of anonymity. In Nickleby, the visual—especially portraiture—seems déclassé, as if the proliferation of representational imagery could erode social and moral distinctions. Or perhaps Dickens is concerned by the proliferation of similarity itself, or simulacra—the proliferation of copying, of nonbiological reproduction. Things should not be made to seem too much alike. The only unqualified form of resemblance we encounter in the novel is the uncanny twinship of the Cherryble brothers, a replication so absolute as to suggest the conventions of religious art. Indeed, one of their roles is to transform a world of commercial replication into something higher and more ordered: they are not simply using money to make more money but are conducting business philanthropically so that even a countinghouse can take account of human character. With them Dickens asks whether a real city can be idealized, an ideal city made visible. What sort of figures might order the confusions of London? Is there a higher form of representation that can be in the city but not of it, a monument to the integrity of moral character that reorders the space in which real characters must live their lives?

Monumental Mapping

You, the Patriot Architect,

You that shape for Eternity,

Raise a stately memorial,

Make it regally gorgeous

Some Imperial Institute,

Rich in symbol, in ornament,

Which may speak to the centuries,

All the centuries after us,

Of this great Ceremonial,

And this year of her Jubilee.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "On the Jubilee of Queen Victoria"

Here I want to move west, from the pump in the square outside the Cheerybles' countinghouse to the much more fashionable strip of land at the southern edge of Hyde Park—the site to be occupied in 1851 by the Crystal Palace and, two decades later, by the Albert Memorial—the same site, filling the same symbolic space. And while briefly deferring an explanation of that last phrase, I want to emphasize the

special role of memorial architecture in a disorderly, jumbled, "provisional" space like that of nineteenth-century London.[4] For a monument like the Albert Memorial performs its most general symbolic function by centering our attention in a city that has no center—no visible topographical or moral center, for point of orientation by which everything else is defined. To some extent for Dickens, this absent center, this lack, is London, a city whose profusion of detail simultaneously stimulates and threatens his imaginative powers. This is the London he sums up in the famous phrase that opens Bleak House: "Fog everywhere." A phrase and not a sentence, since the problem of this novel, this city, is a lack of ordering structures, moral and grammatical, the lack of any principles of light or architectonic stability that is signaled by the book's title. Like the "dark house" of In Memoriam (which appeared just before Dickens began work on the novel), the building called Bleak House embodies a failure of embodiment, a traditional structure drained of traditional significance: it is a body without a soul, a place that cannot be comprehended in any coherent way, an artifact that symbolizes nothing except its own resistance to symbolic order. To such chaos Dickens responds (at the end of Bleak House ) by imagining another building of another kind. He was not alone in using architecture to satisfy such essential needs.

The Victorians constructed imposing monuments to many of their most imposing ideas and beliefs; some of these are monuments to the very idea of such expression, monuments to monumentality itself.[5] The Albert Memorial may be the most striking example of this impulse—a monument I want to consider not simply as an example of the Victorian visual imagination but also as an expression of its power and status, a representation of the role of art within contemporary public life and the life of the modern city. To do so, I emphasize the space it fills—the actual, physical space at the edge of Hyde Park, the moral-symbolic space somewhere in the disorienting blur of nineteenth-century urban life. For the memorial both occupies and redefines space. Occupies it, quite literally, as a finished project, part of a map. But it also functions, more abstractly, as a map—not only filling but representing space, articulating the relations between places, picturing a world larger than itself. I mean in part that the memorial site—like any project on this scale—reconfigures the ground on which it is placed. But something more takes place, since its own iconography makes us aware that this particular site extends outward, into London and toward the rest of the world. From within the city it refigures the city and reimagines the relations of the various figures who people its thoroughfares in a complex global

network. Here, then, is the missing center around which all else can revolve, once and perhaps for all time; in this way, the monument's ambitious claims extend beyond space alone. As a "memorial" it articulates a vision across time, through a kind of prospective memory that locates the present between idealized future and past. I am suggesting that we view the Albert Memorial as a Bahktinian "chronotope," a geo-historical time machine that suspends our motion in time and space to set it going again according to new principles.

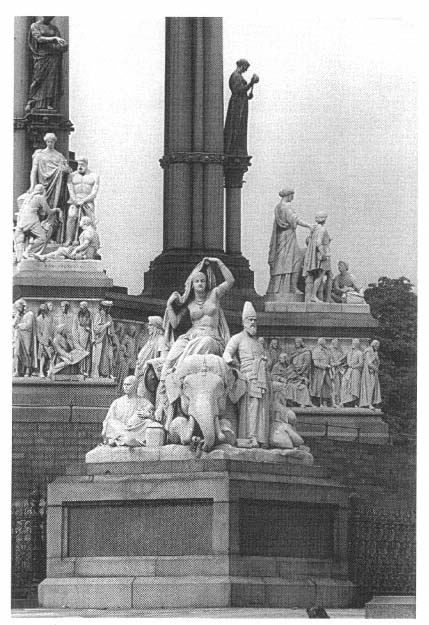

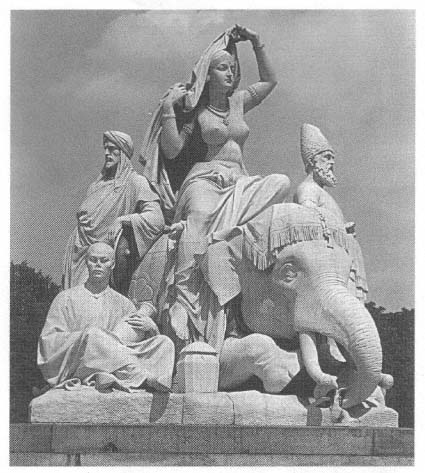

Gilbert Scott designed it as a tribute to the late prince's piety, leadership, wisdom, taste; his dedication to the arts and sciences; his sense of history; and his vision of Britain's role in an emerging international community. Each of those attributes is acknowledged through a separate set of symbolic markers—ranging from angels to animals, from portraits of British artistic notables to representations of the nation's most essential commercial skills, from figures of the arts and their celestial muses to examples of their practical applications in daily life. Albert himself, head bowed beneath a starry dome, holding a catalogue of the Great Exhibition, seems torn between the contemplation of high moral truths and the execution of ambitious industrial projects—thinking globally, acting locally, as our contemporary parlance would have it. But of course Albert's local projects had global implications: the Great Exhibition collected the "Arts and Manufactures of the Nations of the World," according to its own ambitious epithet. Appropriately, then, the memorial is surrounded at the points of the compass by allegories of four continents, each represented by the figure of a native in a complex, but starkly realistic, sculptural design. And it is precisely in the iconography of these figures at the edge of the design—these literally marginal, "foreign" natives at the borders of a highly Europeanized allegorical apparatus—that a mapping process locates London in a larger world and defines the place of those who approach this imagery from the streets. That is the crucial point too often overlooked in discussions of this project: this public art functions in public space and refers at least as much to a public world of living people as to the attributes and ideals of a certain dead white male. Its crowded heterogeneous grouping of figures must be understood in relation to the heterogeneity that is the modern city, its mass of imagery in relation to urban mass experience. The elaborate map it creates is one that includes its spectators, includes us.

The linkage between Albert and the public is established in several ways. The dedicatory inscription, proposed by Victoria, identifies this

as a joint tribute from the queen "and her people," as if to suggest that in the act of memorializing, differences of rank begin to dissolve. Indeed, "her people" might as well read "his children," since the governing metaphor of the whole design is something like what we now term family values. They are implicit even in the idealization of Albert's aesthetic interests: as his central position in the plan suggests, he was not just involved in important artistic projects but fathered them; his very affiliation with the sister arts can be understood as a lofty form of kinship. And the monument is organized to expand this domestic cliché to global proportions, its corners depicting the corners of the world. Paternity, then, reaches fruition in empire: the bordering figures of native women and children represent colonialism as one big, happy, growing family, ordered under the benign influence of the arts and sciences.

But what sort of order is that—how does it work? The memorial offers us few clues, except the fact of order—solid, stable, global, almost magical in its scope. Perhaps the dynamics of Albertian order are mystified deliberately. After all, the subject is a mere prince consort, a man of boundless influence and limited authority. The design alludes to this paradox and in so doing comments on more than Albert alone. Representing the prince as the aesthetic center of the world not only dissociates him from certain forms of power but seems to disavow the power of power itself—as if the word might be understood to mean little more than art or thought, truth or beauty. But the imagery that suggests the beauty of power also discloses the power of beauty. Gilbert Scott liked to refer to the colonial outposts at the edge of the site as "continental sentiments," as if they merely depicted idealized worlds, the figures of Albert's dreams.[6] But the detailed and realistic portrait groups demonstrate that imagination shapes actual places and actual lives, through various more and less aesthetic practices that are shown to be interrelated by the very symmetry of the design. Surrounding the prince are figures of industrial arts and territories, ranged in concentric circles that represent them as analogous, sites of labor and production, sources of wealth and power (Fig. 73). Or this, at least, is the implicit logic of what might be called (I borrow Mark Schorer's phrase) the memorial's analogic matrix. Even in the abstracted contemplation of a catalogue, then, Albert is enmeshed in an interlocking network of industry, finance, and colonial rule; even an aesthetic prince inhabits the world of entrepreneurial capitalism. The monumental syllogisms identify him with both a constitutional and a commercial monarchy, fixed at the center of interrelated circles of production and consumption like the master gear

in some great industrial machine.[7] Thus, while the memorial idealizes an art of leadership, it also acknowledges a global political economy of art.[8]

This discourse on art and power reaches its point of greatest density in the sculptural groups at the edge of the monumental site, each organized around the figure of a woman personifying a continent. These are the chief foreign bodies in this largely domestic design, and it is precisely the relation of foreignness to physicality that charges them with political and iconographic significance. They are, in a literal sense, gendered subjects, figures of simultaneous sexual and political desire: America bare breasted, Africa nearly so. Four continents are depicted in recognition of their contributions to the Great Exhibition. But J. H. Foley's statue of Asia most clearly expresses—or should I say exposes?—the linkage between these different forms of art, industry, politics, power, and lust (Fig. 74). India is shown "unveiling herself as alluding to the great position she took in the exhibition of 1851" (Bayley, 55). In effect, the continent—"unveiling India," as the figure became known—puts herself on display as a tempting consumable delicacy. Subjection is willing, it seems, especially subjection to mild aesthetic power. The kneeling elephant beneath her echoes the same fantasy—in the words of the handbook to the memorial, "the prostrate animal typifying the subjection of brute force to human intelligence" (Bayley, 103). But it is difficult not to notice a less gentle form of power at work. India offering herself—as woman, artifact, and natural resource; as the jewel in the crown of empire;[9] as landscape and people—suggests the connections between imperialism, exhibitionism, and rape. And they are implicit elsewhere. Mythological Europa is most clearly involved in a rape scene, although we might never guess that from the modest representation of the woman and the bull. Again, it is the symmetry of the memorial design that underscores the relation between these places and these experiences: as Africa or India, so America or Europe. The analogical structure of the site defines the whole world as a theater for imperial ambition and imperial power—a power that can be simultaneously magnificent and violent. And if this suggestion seems unsettling when applied to the "distant" sites of empire, it becomes all the more so when the memorial's juxtapositions define a relationship between colonial power and the power operating in modern arts and manufactures. Suddenly, the distance between imperial and industrial subjects collapses. Even the free, modern world of England is subject to the global sweep of Albertian vision and the power it implies.

By now it should be growing clear that the memorial is a map that

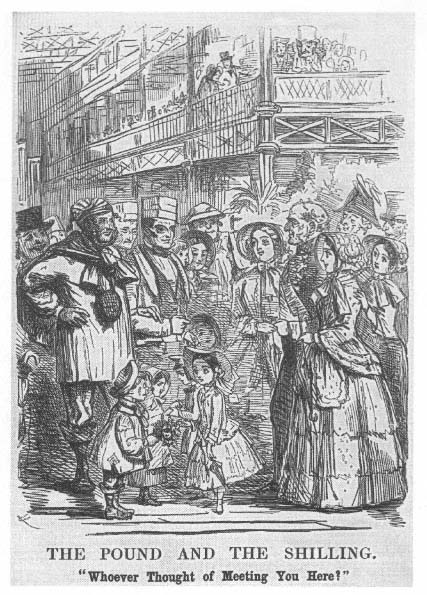

can function in reverse—leading us outward toward a colonial globe only to return again to the imperial context of modern urban life. Thus it is crucial to remember that it is a London monument, of and for the city. The representation of the imperial globe can be seen as simultaneously mapping England, its land and its people, for it depicts the operation of a power that can be exerted in other ways, in other places, over other subjects, abroad and at home. Perhaps it already has been exerted, since power is exercised in this very display, in the mapping that locates us, as urban spectators, within the circuit of imperial aesthetics. Perhaps the real point is that these monumental analogies depict not so much the inert existence as the continuing extension of power—its steady replication and metamorphosis, into various forms and various places, over new spheres and new subjects. And interpretation is one stage in that process, the stage most necessary to confirm our own participation, or complicity, in an imperial mythology and the social conditions out of which it is produced. Hence we are "given" those relatively ordinary realistic sculptures at the edge of the design—figures of the powerless. In part, they represent our presence, as subjects of socio-economic and iconographic authority.[10] They are also reminders of our own capacity to subject and colonize others, to treat them as Others—"natives" related to the London poor Henry Mayhew described as descendants of foreign nomadic tribes. Scott was attentive to the compass position of the various elements of the design, so it may be significant that the groups representing the most primitive reaches of empire, Asia and Africa, stand at what we might call the east end of the memorial, linked to the part of the city associated most often with the poor and third-world immigrants. It certainly is significant that this interaction of iconographic types takes place in Hyde Park, where the interaction of social classes had provoked so much uneasiness in the commotion surrounding the Second Reform Bill of 1867, or even in the discussion of cheap admission to the Great Exhibition in 1851. John Leech's famous Punch cartoon on different classes of visitors to the Crystal Palace (Fig. 75) makes light of the social mingling that proved so serious a topic for many Victorians—like Matthew Arnold, who regarded one notorious example of it in Hyde Park as anarchy. The Albert Memorial treats the same problem with no trace of Punch 's humor or Arnold's hysteria, locating the interaction of different human types within a stabilized framework, on a site that has been carefully redesigned and redefined. Now all visitors, rich and poor, British and foreign, can be spectators together in a Hyde Park carefully mapped as an area for enlightened leisure, a neutral space between the class-specific regions of Greater London and

its expanding suburbs, a zone reserved for the dispassionate contemplation of social relations and social limits.

I have called the memorial a time machine, but it is no less a power machine, a device for simultaneously representing, exerting, and rearticulating authority. It is not so much an objective presentation of certain fixed global facts as a symbolic restatement that in the very act of representing the imperial world extends and solidifies its sway. Hence the intricate detail of the memorial iconography: it invites interpretation, solicits interpreters. Reading this imagery, entering the iconographic precincts of this miniaturized aesthetic-imperial city, we participate in its divisions and exclusions. It is, then, a monument not to Albert alone but to the methods (iconographic, psychological, sociological, disciplinary) by which his memory is preserved, a monument to the place of aesthetics in the broad spectrum of practices we might term the Victorian arts of social control. It reminds us that these arts function in a circuit, not only extending outward to the edges of empire but also returning to articulate the art of power, and the power of art, at home. Viewing the memorial from the edge, we all become subject to the colonizing power of Victorian culture, street figures ranged along the receding avenues of empire.

Chinatown

To see clearly is Poetry, Prophecy, and Religion, all in one.

John Ruskin, Modern Painters

I have been asking how we read cities. Now I must ask whether we ever really do. Can there be such a thing as "reading" when the text itself is so problematic, so complex, so overlain with the multiple screens of our own perceptions? Can we look at New York without seeing Los Angeles, or Santa Cruz, or Woody Allen's films? Could the Victorians look at London without seeing other places, real or imagined,[11] as close as a remembered countryside or as far away as exotic colonial capitals halfway around the world? The last question becomes increasingly important as the century progresses: it is difficult to focus on any point of the map when one has been schooled to think internationally. How can one read a city in an imperial century? The Albert Memorial imports colonial imagery into a monumental urban grid derived in part from other responses to subjected native peoples abroad—themselves first "seen" in terms of models originally conceived in En-

gland. The city we think we see is already contaminated by those we think we have forgotten.

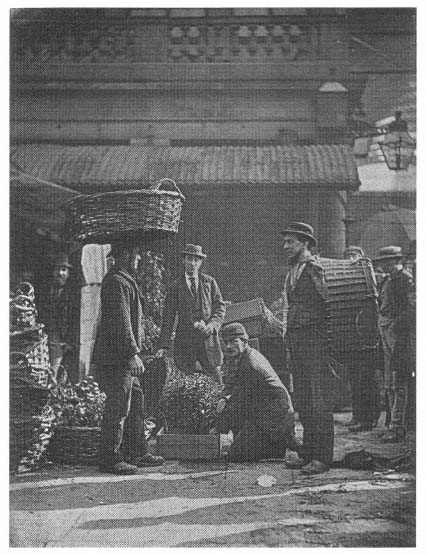

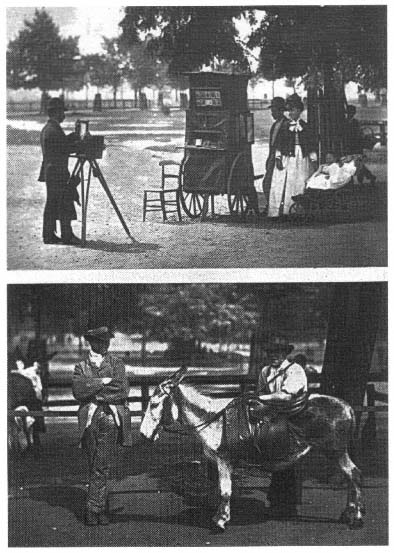

The same complex circuit of perception and memory recurs throughout the various nineteenth-century efforts to "know" the city and its inhabitants. Even photography—the art form that seems to be most simply and directly representational, most radically innovative, least mediated by the human operation of its technologies[12] —participates in this process, and only "reveals" a city that had been discovered and defined elsewhere, in prior traditions of representation. I will close by considering briefly the complex, global, matrix of perception that structures one of the most important examples of early urban photography, a volume that makes explicit claims to a radical realism (claims that have been reasserted by virtually all subsequent photographic historians and commentators on the book). Street Life in London —a socio-journalistic collection of texts and photographs examining the poorest corner of the city—was published in 1877, just after the completion of the Albert Memorial. The book presents the collaborative work of Adolphe Smith and John Thom(p)son[13] —the first providing a text in the tradition of Mayhew and perhaps Dickens, the second (although, as we will see, he wrote some of the text as well) supplying the powerful images that gave the book its celebrity as a classic of sociological photography and reformist sympathy. The photographic historian Roy Flukinger writes of Thomson's "serious commitment to his subjects and his art . . . his compassion."[14] The preface to Street Life makes the point first, in case we miss it in the rhetoric of images alone: "as our national wealth increases," we cannot "be too frequently reminded of the poverty that nevertheless still exists in our midst." "The Authors" acknowledge their debt to Mayhew but insist that the "facts and figures" of London Labour and the London Poor are "necessarily ante-dated," above all by the "precision of photography. The unquestionable accuracy of this testimony will enable us to present true types of the London Poor." And to present them in true settings as well: "We have selected our material in the highways and the byways, deeming that the familiar aspects of street life would be as welcome as those glimpses caught here and there, at the angle of some dark alley, or in some squalid corner beyond the beat of the ordinary wayfarer" (Thomson, 1969, preface). Street Life alters London Labour by shrinking the role of text while expanding that of illustration, and by replacing Richard Beard's simple woodcuts of isolated figures (themselves based on daguerreotypes) with photographs showing people in surroundings we can see in detail (Fig. 76). Here, perhaps for the first time, we actually see street figures, figured on the streets. As

one modern reprint insists, "Thompson's photographs seem designed to let the reality of London speak for itself, as if the photographer felt these facts were drama enough, needing no theatrical touches from his hand."[15] Flukinger makes a similar assessment: "Thomson captured his subjects in situ, arranged in a naturalistic manner and looking as if they were depicted instantaneously from everyday life. By keeping the people in their day-to-day context and by having them relate to each other and to their environment, he brought Realism [sic] into the documentary photograph" (Flukinger, 83).[16] My own response to these images is more qualified: they express a powerful sense of social reality while also suggesting the presence of the camera and photographer in explicitly dramatic "scenes," arranging bodies and commanding attention. The fixity needed for a long, clear exposure also produces a sense of artificiality, and with it a sense of social hierarchy. Thus, even with the democratizing aim of journalistic exposé, the authority of the camera intrudes itself—organizing bodies, controlling action, creating distance. Standing behind the camera, we remain outsiders, tourists. It is as if we are seeing "foreigners"—and the effect would be the same even if "we" were nineteenth-century Londoners seeing the images when they first appeared. These photographs, despite or because of their self-proclaimed politically sympathetic impulse, exoticize London, as if the East End were a distant corner of the world—as if it were Chinatown. And if this perspective seems in part a function of our own associations with the camera—the invariable companion in our travel and leisure activities—that "modern" notion of socio-photographic perspective also has a history, one that begins to emerge in this volume of Thomson's and from its antecedents.

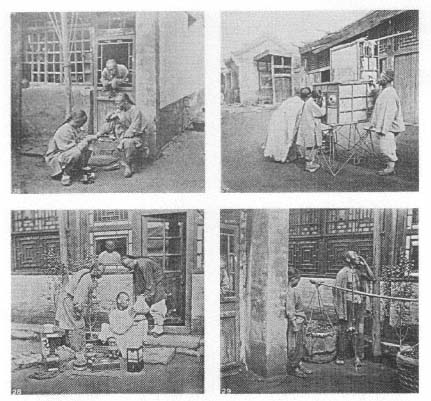

In the early 1860s John Thomson left Edinburgh for Asia, setting up photographic studios on the island of Penang and later Singapore, where he photographed "a broad variety of races, including 'descendants of the early Portuguese voyagers, Chinese, Malays, Parsees, Arabs, Armenians, Klings, Bengalees, and Negroes from Africa.'" He soon tired of studio work, concluding that "the most interesting subjects for his photographs lay in the streets and countryside outside his studio."[17] Thomson produced nine books of photographic exploration in eastern and southeastern Asia, India, and Cyprus, developing a technique that attempted to fit his Western background to the special demands of Eastern experience. His essays acknowledge a real difference in Eastern and Western aesthetic principles, and at least claim to take it seriously. The result, according to Stephen White, the photographic historian who is his main biographer, is a method that expresses the tension between the

two perspectives. Thomson thought of composition in Ruskin's terms: "literally and simply, putting several things together, so as to make one thing out of them" (White, 40). He insisted that his own "share in the composition is very very small indeed; I have only permitted nature to do what she is always willing to do, if photographers do not stand in her way."[18] For White, one consequence is an avoidance of the "traditional Western view of nature as subordinate to man. Thomson's own view of the relation of man and nature is more Eastern than Western. In seeing himself as the medium or interpreter of a scene to be photographed, he does not set himself above his subject." The same principle is visible in his photographs of people (Fig. 77): "the poorest farmer, or simplest beggar, has a dignity which he seeks to capture. Thomson portrays his subjects just as they lived in their own worlds" (White, 41). Hence, in Street Life in London, "The hopes and aspirations, values and needs of those portrayed were recognizeable to readers of other classes. . . . Through his China work, Thomson had become so adept at posing people in a natural way that the scenes appeared entirely spontaneous" (White, 31).

Those are loaded terms, and hardly new ones. The emphasis on spontaneity restates an ideology that had been part of the history of photography since the publication of Fox Talbot's pioneering collection with its revealing oxymoronic title, The Pencil of Nature .[19] Thomson's title makes a parallel assertion of realism, yet perhaps also hints at a qualification. The phrase "Street Life" itself suggests a category of pictorial convention, something like "living genre scenes." Part of the fascination of these images—all the more powerful for being set in the recognizable, random activity of modern urban life—is the juxtaposition of formality and the accidental, the palpable illusion of spontaneity. The reality is just stagy enough to unsettle our first impulse to offer a straightforward socio-moral reading. Much as in Nicholas Nickelby, thecity is overlain by the theater, and simple "seeing" replaced by what Jonathan Crary has called techniques of the observer. Similarly, Thomson's sympathetic humanitarian politics are articulated by the machinery of a new technology, a modern art that (much as in the case of the Albert Memorial) is defined partly in relation to the imperial globe. For to a significant extent Thomson's celebrated urban realism derives from the methodology of his Asian documentaries;[20] these sympathetic glimpses into familiar daily life grow out of a highly developed colonial gaze, embedded in the relations of class and racial types. Once again, "reading" the city involves an exercise of power—a power first defined elsewhere and always understood as international in its reach. Thomas

Prasch, who examines the same "mirroring" effect, has shown that Thomson's account of Asian peoples imposed "the social categories applied to the working class of Victorian England."[21] No wonder, then, that in Thomson's London pictures all the figures become "examples" of something, "true types" as in Mayhew: the very formality of the photographic iconography suggests that to respond to them requires some larger set of generalizations, those, for example, of the sociologist or anthropologist.[22] In this sense, our apparent proximity to the poor in early documentary photography simultaneously involves a new distance—and a new technique of distancing—related to, but not wholly derived from, the technological possibilities of the medium itself. Street figures must be refigured—or disfigured. We see them through a particular lens, and from a particular angle, as Others and in terms of other Others still.

Thomson's own written contributions to Street Life in London refer to his Asian experiences at several points; Prasch suggests that the comparison of Mongolians with the "London Nomades" who form the subject of the first plate prepares the way for an anthropological racial politics that recurs throughout the book (15–16). At times the allusions seem far more innocent. In his most extended and most curious reference to Asia, Thomson compares the popular reaction to floods in Lambeth and China to argue (perhaps with both Mayhew and Dickens in mind) that

The Chinese, who are eminently an agricultural people, turn the dust and refuse collected within their abodes to better account than we do in London. . . . If a body of Chinese emigrants had to deal with the garbage of a city so vast as London, we should find many of the poorest lands around the metropolis transformed into gardens and markets stocked with even a more abundant supply than we already possess of the choicest fruits and vegetables.[23]

The traveler measuring the commercial possibilities of urban conditions discloses the vantage point from which he views these London natives, a position of superiority we are invited to occupy as well.[24] In part, then, this nineteenth-century anticipation of Margaret Thatcher's Victorian social theories assesses the potential "value" of the poor to the nation. The glance toward China effectively classifies the London poor as a discrete national/racial unit, whom we are to evaluate according to their collective contribution to "the rest of us." Street Life in London implies the same stance, depicting its gallery of human curiosities with a starkness that almost compels us to regard them as foreign. The allusions to other people in other places, other "subjects," only intensify the effect:

the documentary close-up creates its own form of distance. A Thomson photograph, like the Albert Memorial, is an urban time machine that moves us simultaneously nearer to and farther from the streets. Equally important, it helps define a new methodology of urban perception and representation, an iconography of social realism that has stayed with us. These apparently transparent images structure the world they represent and the way we view it. Surveying London through this lens, we learn what it means to "see" the city through the representations of it in the most radically modern art. We learn, that is, to see locally and think globally, to locate the "realism" of urban photography in a complex circuit of information, a highly articulated structure of perception and allusion.

In this sense, documentary photography did not so much transform as replicate the basic conditions of Victorian urban art and nineteenth-century realistic representation more generally.[25] If there is a common thread linking all the modes we lump under the category of realism, perhaps it is a reflexive insistence upon their own limits as realism, upon our own limited access to the real. Cities may have been the most familiar sites for early realist works precisely because they were so closely associated with that reflex of double vision, that sense of what we can and cannot see, can and cannot represent directly. Victorian urban iconography repeatedly reminds us of our position within, and distance from, urban life, repeatedly insists that the city is a simultaneously familiar and foreign world.[26] Typically, then, the Victorian urban artist struggles to be in but not of the city, to find a way to keep vivid close-ups at arm's length. The very idea of a more direct representation, of a pure, simple urban artist remains suspect, too closely implicated in the world one seeks to depict: a figure like Miss La Creevy is symptomatic of what Dickens regards as the power of London to miniaturize our lives and our work, and we find similar suggestions in other places and other forms of art. Thomson's image of the urban photographer suggests a related discomfort with a role not unlike his own—one of several "Clapham Common Industries," as the accompanying text is captioned, in which the artist becomes another proprietor "Waiting for a Hire" (that is the phrase attached to the donkey keeper shown here in Fig. 78). The very existence of a volume like Street Life in London is predicated on the value of putting art to work in the city; yet the conjoined texts and images cannot avoid acknowledging—or else, do not manage to repress—an uneasy recognition that all city work can be reduced to the same level, that even the arts can be compromised by excessive lingering on the streets. Is that the hidden warning behind the threadbare group

of Italian street musicians huddled in awkward poses? It is as if all urban artists become foreign artists, alien and impoverished, as if urban art and the urban artist operate under an inescapable threat. No wonder Nicholas Nickleby concludes with another imagery, in another world—a dreamy, pastoral setting deliberately located outside the territorial ambitions of realism—where urban conditions are only a memory, where texts are always stable and benign, and where no street life exists to complicate the way we look, the way we live, or the way we see.

Fig. 70.

Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), "A Sudden Recognition, Unexpected on Both Sides,"

from Nicholas Nickleby, 1838-39. Photograph courtesy Department of Special

Collections, Knight Library, University of Oregon.

Fig. 71.

Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), "Nicholas Starts for Yorkshire," from Nicholas Nickleby,

1838–39. Photograph courtesy Department of Special Collections, Knight Library, University of Oregon.

Fig. 72.

Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), "Nicholas Hints at the Probability of His Leaving

the Company," from Nicholas Nickleby, 1838–39. Photograph courtesy

Department of Special Collections, Knight Library, University of Oregon.

Fig. 73.

Gilbert Scott et. al., Albert Memorial, 1872. Photograph courtesy Conway Library,

Courtauld Institute of Art.

Fig. 74.

J. H. Foley, Asia, Albert Memorial, 1872. Photograph courtesy Conway

Library, Courtauld Institute of Art.

Fig. 75.

John Leech, "The Pound and the Shilling," from Punch 20 (14 June 1851).

Photograph courtesy The Department of Special Collections, The Knight Library,

University of Oregon.

Fig. 76.

John Thomson, "Covent Garden Labourers," from Street Life in London, 1877.

George Eastman House.

Fig. 77.

John Thomson, "Street Amusements and Occupations, Peking," from

Illustrations of China and Its People, 1873–74. George Eastman House.

Fig. 78.

John Thomson, "Clapham Common Industries: 'Photography on the

Commons' and 'Waiting for a Hire,"' from Street Life in London, 1877.

George Eastman House.