Chapter Eighteen

Agony at the FBI: Louis Budenz

In his March 30, 1950, speech to the Senate, McCarthy did not unleash his full anti-Lattimore arsenal. Perhaps he calculated that the Kohlberg and Utley materials and his phony Barmine affidavit would be sufficient. If so, he was mistaken. The widespread skepticism about his performance necessitated using everything he could muster. None of his early witnesses was top drawer. Kohlberg was recognized even by McCarthy's staff as disreputable. Utley was more respectable but did not make a good witness. Barmine had only hearsay to offer and was reluctant to offer that. McCarthy needed a Whittaker Chambers. J. B. Matthews provided the connection to a witness far more voluble than Chambers—the former Communist Louis Budenz.

The FBI had followed the career of Louis Budenz since his graduation from Indianapolis Law School in 1912: assistant director of the Catholic Central Verein in St. Louis, secretary of the St. Louis Civic League, publicity director for the American Civil Liberties Union, ten years (1921-31) as editor of Labor Age . The bureau had reports on his strike organizing and many arrests in Kenosha, Wisconsin; Patterson, New Jersey; and Toledo, Ohio. They knew he had worked with agitator A. J. Muste, had flirted with Trotskyism, and in October 1935 had joined the Communist party. As a Communist he served as labor editor of the Daily Worker in New York, then as editor of a Communist paper in Chicago, and finally as managing editor of the Daily Worker , where he also served as American correspondent for the London Daily Worker . Hoover had copies of all Budenz's dispatches to London; these articles agitated Hoover greatly, and he pushed hard to get Budenz indicted for failing to register as a foreign agent.[1]

Budenz claims in This Is My Story that all through his Communist years he sought to reconcile Communist doctrine with Catholicism; by 1945 this reconciliation appeared impossible, and he contacted Monsignor Fulton Sheen about rejoining the Church. Sheen encouraged him. Without letting his Communist comrades even suspect his approaching defection, on October 10, 1945, Budenz was received back in the church at a ceremony in St. Patrick's Cathedral. The next day he took up a professorship at Notre Dame.[2]

Sheen tipped off Hoover in advance about this defection, so the bureau was ready to move rapidly in debriefing Budenz. Special Agent J. Patrick Coyne of bureau headquarters talked to Sheen, who in turn negotiated with Budenz and Notre Dame. Budenz was wary about talking to the FBI; he was afraid that if word got out to his former Party associates, his personal security would be jeopardized. If he agreed to talk, he wanted Catholic agents to interview him.[3] Sheen checked out this request and was assured that the bureau would maintain confidentiality. Two Catholic agents, Coyne and Winterrowd, were ordered to prepare questions to put to Budenz. They took two rooms in a South Bend hotel; technicians were in the extra room recording everything Budenz said from a hidden microphone. Budenz did not know for thirteen years that he had been recorded.

The bureau's Communist experts, working with Coyne and Winterrowd, prepared seven hundred questions to put to Budenz, grouped under twenty-one headings. Two of the headings, "Communist controlled and influenced groups" and "Communist propaganda and publications," required him to tell what he knew about the IPR. In addition, seven questions related to the Chinese Communists and their American supporters.[4] Coyne and Winterrowd interviewed Budenz December 6-12, 1945, from three to five hours each day, skipping only one day. At the end of the series Coyne telephoned a preliminary report to Washington. Budenz, Coyne said, was cooperative and sincere: "Mr. Coyne stated he is not, however, as well informed as expected and they have confronted him with that fact, and he said he realizes this and attributes it to the fact that during the last several years, with the exception of one other man, he has been the only American Communist connected with the National Committee. The rest of them have been Moscow-trained either at the Lenin or Wilson School. He believes, and Mr. Coyne stated he was also of the opinion, that they have not taken him into their complete confidence. . . . Budenz is strictly a Labor man and knows what it is all about."[5]

Not "well informed" about the Communist party that he had served so loyally for a decade? The slight to Budenz's ego from this disparagement

must have stung him severely. His entire subsequent career can be read as an attempt to escape this stricture, to escape the narrowness of his labor specialty, to appear as a savant on communism in all its forms and variants.

The tapes of these South Bend interviews were transcribed, and Winterrowd condensed the substance into eighty-six pages. Budenz had actually covered a lot more than labor affairs. There was at least one gaping hole, however: his knowledge of Asia was thin. In regard to the question about "persons supporting the pro-Communist Chinese" he denied that Edgar Snow was a Communist, claiming instead that "Harrison Forman was considered closer to the Communist Party than [was] Snow" and that Philip Jaffe was clearly a member. No others were mentioned.[6]

When it came to the IPR, Budenz was hardly more expansive: "The Institute of Pacific Relations, he said, was Communist inspired '100 per cent.' He later changed this statement to say that it was controlled by the Communists. With regard to one of its main officers, Edward Clark Carter, he said that he could not say Carter was a Communist but that he was looked upon as a Communist by 'those of us who had to deal with him.'" No one else was worthy of mention.[7]

Budenz was expansive about the subservience of the American Communists to their Soviet masters. The shadowy characters who flitted in and out of Party headquarters in New York disturbed him greatly, as did the "conspiratorial" activities of the Party. And he "identified a number of prominent people who have been on the fringe of the Communist movement in the sense that he, as a member of the National Committee of the Communist Party . . . considered them in that light . . . . Among those he named in this category was Congressman Hugh DeLacy of the State of Washington." And Budenz was more than willing to testify in behalf of the government in cases involving Communists, though he wanted a period of time to reorient his life and refresh his memory before he was called on. Coyne and Winterrowd arranged for him to contact the Indianapolis office should he recall additional pertinent information.[8]

Budenz's stay at Notre Dame was not very satisfactory, and after a year he moved to Fordham University. There he came under the bureau jurisdiction of Alan Belmont, at that time assistant special agent in charge of the New York office. Belmont soon discovered that Budenz was intent on pursuing a career of professional witnessing. He began to make anti-Communist speeches for Catholic groups and to give interviews to journalists. In October 1946 Budenz talked to a reporter about Hans Berger (alias Gerhart Eisler), whom he described as the chief Soviet overseer of

American Party affairs. This information the bureau found "disconcerting": they were investigating Eisler quietly, but now they had to tie up personnel on surveillance. Belmont wanted assurance from headquarters that "the New York Office would not be held responsible for any control over Budenz and would not be held responsible for any statement or action by him without Bureau knowledge." He got this assurance, but the bureau did want advance word of any proposed statement or action by Budenz in the future.[9]

In November, after Budenz appeared before HUAC, Coyne and Winterrowd met with him in Washington. In a long report Coyne revealed that Budenz thought the HUAC members "were not fast on the pick-up" when he mentioned matters of importance; they seemed more interested in personal publicity than in promoting the security of the United States. This was one of the few matters on which Budenz agreed with the Left. Ernie Adamson, of the HUAC staff, had even asked Budenz to attack several congressmen, specifically Claude Pepper of Florida. Budenz de-dined. He also told the FBI men that his book This Is My Story would be out by Christmas 1946 and that Father Cronin had written him suggesting that he affiliate with Plain Talk , a new ultraright magazine financed by Alfred Kohlberg. At the close of the interview Budenz indicated that he would be happy to assist the bureau with a brief on the Communist movement.[10] It was a good interview. Budenz appeared to be under control.

Accordingly, the New York office began to consult Budenz regularly, averaging once a week. He was more than willing m talk about most of the questions they raised, and when he didn't have an answer ready at the first inquiry, he would think about it and refresh his memory for the next week.[11]

On March 12, 1947, New York agents spent several hours with Budenz, getting his views on William Z. Foster, Steve Nelson, Earl Browder, and other Party notables. During this interview Budenz volunteered a new source of information for the bureau: Alfred Kohlberg had been to see him and had told him about the IPR, its pro-Communist propaganda, and how Kohlberg was trying to reform it. Kohlberg had wanted to know if Budenz could "give him some information on the members of the Executive Committee relative to their Communist tendencies." Budenz could and did. He now knew four Communists on the IPR executive committee: Edward Carter, Harriet Moore, Fred Field, and Len DeCaux. Budenz told the FBI that Kohlberg was grateful for this information and that he and Kohlberg had become fast friends.[12]

Five months after his first talk with Kohlberg, Budenz was interviewed

about the IPR by Daniel H. Clare, Jr., of the State Department. Budenz told Clare "that he was not prepared to pass judgment upon the degree of Mr. Lattimore's association with the Party. He is aware that he is a sympathizer, but is unable to recall at this time any incidents which definitely indicated that he was a member of the Party." The bureau thought Clare's report was worthless. Belmont noted that Clare depended primarily on Kohlberg and said the report contained "many inaccuracies."[13]

By 1947 Budenz was being used by the Immigration and Naturalization Service as a witness against various Communists in deportation proceedings. One of these proceedings was particularly painful. On September 17, testifying for the government In the Matter of Desideriu Hammer, alias John Santo , Budenz's credibility was challenged on the grounds that he had committed bigamy and violated the Mann Act. Under cross-examination by Santo's lawyer, Harry Sacher, Budenz took the Fifth Amendment twenty-two times to avoid incriminating himself.[14] The story that carne out of the Santo hearing is best told by Jack Anderson.

The transcript [of Santo] revealed a more colorful past than was hinted at by the austere comportment of the present Fordham professor. During those halcyon days before his conversion, when Budenz the Communist was plotting murder attempts on Trotsky and stage-managing a plague of labor disruptions for which he was arrested twenty-one times and acquitted twenty-one times, and even before he formally joined the party, the good doctor was sampling the one compensatory amenity which Communist discipline, that harsh mistress, permitted her disciples—sexual philandering. While married to one woman, Budenz had lived with a second for several years. A third female showed up with him on various hotel registrations in Connecticut, Pennsylvania and New York. In the wake of all this there were three illegitimate children, a trail of forged hotel registrations and a divorce on grounds of desertion. After Budenz reconverted to Catholicism and conventionality, he tried, naturally enough, to put the most decorous face possible on things for the sake of all concerned. He faked a marriage date in his self-penned Who's Who biography; stumbled lamely in the timeless manner of errant husbands who are ambushed, through interrogatories about his incontinent past; and even took the Fifth Amendment about some of his trysts. It was a document filled with the small personal confessions which our adversary system wrenches from witnesses to large conspiracies, yet it raised valid questions about a credibility that had assumed crucial proportions.[15]

Publicity from the Santo case grieved the bureau, which was depending on Budenz for continuing revelations about Communist functionaries and

crimes and expected to use him in important prosecutions yet to come. If he were alienated by embarrassing cross-examinations in piddling deportation cases, the anti-Communist cause would suffer. Agent Coyne was particularly worried about this development. On October 1, 1947, Coyne conferred with a Justice Department attorney who had followed the Santo case; the attorney "doubted very much if Budenz would ever want to testify again in any Government case, in view of the derogatory publicity which appeared in the press concerning Budenz" after the Santo hearing. Coyne wrote Ladd recommending that the bureau pressure Justice to curb use of Budenz for such trivia, saving him for continued use as a bureau informant and for important future trials.[16] We do not know Ladd's response; Budenz continued to serve as a witness in relatively trivial proceedings.

The bureau was not happy with Budenz's increasing association with Kohlberg, whom they regarded as unstable. In December 1947 Budenz revealed to Coyne that he was considering establishing a relationship with Counter Attack , an ultraright magazine run by Theo Kirkpatrick, a former FBI agent for whom Hoover had a deep antipathy. Kirkpatrick was luring Budenz with access to a cache of "secret records" kept in the Counter Attack office. Coyne warned Budenz against Kirkpatrick, fearing that association with Counter Attack would further damage Budenz's credibility. The warning went unheeded. Budenz not only took up with Kirkpatrick but also became consulting editor of the magazine; he later had his own anti-Communist newsletter printed on the Counter Attack press.[17]

In 1948 the bureau had clear warning that Budenz was capable of serious exaggeration. The New York Sun of April 27 carried a story head-lined, "Budenz Bares Communist Plot to Infiltrate National Guard." The article caused great consternation both in New York and Washington. Agents were immediately sent to interview Budenz about it. After this interview and an examination of Budenz's previous statements to the bureau Ladd sent Hoover a six-page analysis of the incident. On one of Budenz's more startling claims to the reporter, Ladd noted that "Budenz advised Bureau agents that he had no actual factual support for such a statement." Ladd's conclusion was the first explicit bureau challenge to Budenz's general credibility: "It should be borne in mind that Budenz apparently is inclined to make sensational charges which the press interprets as startling new information when, in fact, the information is old and not completely substantiated by actual facts."[18] This, like many subsequent warnings, went unheeded. The bureau investment in Budenz was already too great to permit open acknowledgment of his unreliability.

In August 1948 New York SAC Scheidt noted another disturbing de-

velopment. Budenz had frequently mentioned his need for a set of old issues of the Daily Worker to use in "refreshing his memory" concerning the many persons and events he was giving testimony about. Now his friend Alfred Kohlberg had come to his aid. Kohlberg bought a set of the Daily Worker covering the period of Budenz's Party membership, 1935-45, and lent it to Budenz. Observed Scheidt: "Since Professor BUDENZ is using Mr. KOHLBERG'S set of 'Daily Workers,' he is to a certain extent obligated to Mr. KOHLBERG . This is not the most desirable situation."[19]

Perhaps it was not desirable for the bureau. For Joe McCarthy, anything furthering the Kohlberg agenda was eminently worthwhile. Should Budenz support Kohlberg, and hence McCarthy, in early 1950, it would be a godsend.

At the beginning of 1950 Budenz had not yet weighed in against Lattimore. So far as anyone knew, Budenz had never met the Johns Hopkins professor and knew nothing about him. The Soviet conspiracy in which Budenz had played a role, about which he testified so extensively to the FBI, to the Foley Square trial of the top Communist leaders, and to HUAC, did not even have a China connection. When Budenz wrote his first book in 1947, he was totally unaware that China was the master key to a "Red White House"; this geopolitical doctrine appeared for the first time in his Collier's article of 1949.[20] Even then Budenz had nothing to say about Lattimore; Earl Browder was the "mastermind" of Kremlin machinations to install a Communist government in China and thus to open the door to Communist conquest of the United States. And, according to Budenz, Lattimore was not among Browder's five accomplices.

In 1950 Budenz's flair for the dramatic burst wide open. His devoted wife knew about this tendency even better than the bureau. According to her, Budenz was a master at entertaining their children with marvelous "Pumpernickel tales" invented through the "magic of his imagination."[21] In 1950 he turned this imagination to inventing tales about Lattimore.

J. B. Matthews, who knew Budenz well, sensed that he might be ripe for a new arena of witnessing. Clearly HUAC, court trials, and deportation hearings were being upstaged by the flamboyant McCarthy. McCarthy had written Budenz March 14 asking if he knew anything about Lattimore; Budenz did not answer.[22] But Budenz could not turn down a call from his good friend Matthews. When Matthews phoned March 25, Budenz was cordial. Matthews recorded the conversation without Budenz's knowledge. Several days later Matthews gave a copy of the transcript to the FBI. It is startling. Had this transcript been public at the time, Budenz's credibility would have suffered immeasurably.

Budenz's public posture was that of a reluctant witness, similar to

Chambers, who testified against those he claimed to be Communists only under subpoena and with great anguish. Chambers, however, was sincere; the Matthews transcript shows Budenz to have been a hypocrite. The bureau regarded this transcript as so important that half a dozen copies are scattered through the Lattimore file, and one was sent to the attorney general. After casual preliminaries, the conversation got down to business:

Matthews : Would you be able if called upon to identify Owen Lattimore as a party member by virtue of your position on the DAILY WORKER?

Budenz : Ah, you mean if I were subpoenaed?

Matthews : Yes, that is what I mean.

Budenz : It would be hearsay identification.

Matthews : It would be, as I understand it, from one of our mutual friends—you know whom I am talking about?

Budenz : Yes.

Matthews : It would be because you had to know in your job?

Budenz : That's right. I know 400 concealed Communists, J. B. that I cannot mention.

Matthews : I understand.

Budenz : Because if I did, why there would be such a furor that I would be discredited.

Matthews : Yes.

Budenz : That's why I am taking the thing seriatim so to speak. . . . I have several irons in the fire. I am eager to expose Field and Jaffe and the whole set up.

Matthews :Yes, that whole Far Eastern business?

Budenz :Yes. The only thing is, I want to do it in such a way that I don't appear to be too partisan, you know.

Matthews :Right.[23]

It is noteworthy that even at this late date, on March 25, 1950, Budenz still had not zeroed in on Lattimore. He would testify about Lattimore, but he was "eager to expose" only Field and Jaffe. With McCarthy's speech of March 30, when Lattimore was put dead center, Budenz's priorities shifted accordingly. He had now come full circle. Whereas in 1949 his litany of Soviet machinations did not even include Lattimore, two years

later his recollections of Lattimore's misdeeds filled eleven single-spaced pages of an FBI summary.[24]

The FBI was late in learning of Budenz's sudden concern about Lattimore. On March 26, 1950, Hoover routinely instructed the New York FBI office to check with Budenz about his Collier's article. If the IPR had influenced China policy and Lattimore had been editor of the major IPR publication, perhaps Lattimore had "knowingly assisted Communists in such activity" during his editorship.[25] Scheidt sent an agent to see Budenz the next day. His report to headquarters set forth the new revelations.

CONCERNING LATTIMORE, BUDENZ ADVISED THIS OFFICE ON MARCH TWENTYSEVEN THAT HE HAD NEVER MET HIM BUT HEARD ABOUT HIM MANY TIMES, PARTICULARLY AT POLITICAL COMMITTEE MEETINGS OF PARTY WHEREIN FREDERICK V. FIELD MADE REPORTS. IN THESE REPORTS FIELD STATED THAT LATTIMORE WAS GIVEN CERTAIN ASSIGNMENTS, OR HE REPORTED ON WORK DONE BY LATTIMORE. THERE WAS NO QUESTION IN BUDENZ'S MIND THAT LATTIMORE WAS A COMMUNIST. BUDENZ KNEW THIS FROM THE WAY FIELD REPORTED ABOUT HIM. BUDENZ ALSO HEARD HARRY GANNES REPORT ON LATTIMORE. BUDENZ BELIEVES HE FIRST HEARD OF LATTIMORE WHEN LATTIMORE WAS WITH THE IPR PROBABLY AROUND NINETEEN FORTY. FIELD REPORTED TO POLITICAL COMMITTEE ABOUT WORKING WITH LATTIMORE AND JAFFE. BUDENZ CONTINUED HEARING ABOUT LATTIMORE AS A COMMUNIST UNTIL AT LEAST NINETEEN FORTY FOUR. BUDENZ RECALLED THAT IN NINETEEN THIRTY SEVEN FIELD WAS REPORTING ON CHINESE MATTERS AND THE POLICY OF PLAYING UP THE AGRARIAN REFORM MOVEMENT IN CHINA AND MAKING IT APPEAR THAT THE CHINESE COMMUNIST MOVEMENT WAS REALLY THE AGRARIAN REFORM MOVEMENT. THIS IDEA CAME FROM BROWDER. THE ACTUAL CARRYING OUT OF THIS POLICY TOOK PLACE LATER. LATTIMORE WAS GIVEN THE ASSIGNMENT OF CARRYING OUT THE CAMPAIGN OF PUTTING ACROSS THE IDEA THAT THE CHINESE RED MOVEMENT WAS REALLY THE AGRARIAN REFORM MOVEMENT. BUDENZ HEARD THIS IN A REPORT BY FIELD. BUDENZ STATES ONLY A TRUSTED COMMUNIST WOULD BE GIVEN THIS ASSIGNMENT .[26]

Rubbing salt in the wound, Howard Rushmore published an article in the New York Journal-American on March 30, 1950, headlined, "FBI Is

Probing Lattimore Here": "One witness who knew Lattimore in China has been living here for more than a decade. Yet he was never interviewed by the FBI until the McCarthy charge against the Far East 'expert' was made public."[27]

There it was, all laid out in cold print: the bureau competing with McCarthy to see who could get to witnesses first and the demeaning claim that the bureau was acting only after McCarthy had publicized Lattimore. When the Rushmore article got to Hoover, he forwarded it to Ladd with a peremptory question: "This is what I feared. Just why wasn't this case intensified sooner?"

The bureau still did not know for sure who McCarthy's mystery witness was. Ladd ordered Belmont to find out. On April 1 Jean Kerr identified Budenz. By April 2 the bureau high command had seen the Matthews-Budenz phone transcript and knew that Budenz would be called to testify before Tydings, that his testimony would be hearsay, and that he claimed that he could identify four hundred "concealed Communists." Hoover ordered New York agents back to Budenz. On April 4 they interviewed him again. His "new" information about Lattimore was from the old Kohlberg charges: Lattimore had "played a big part publicly" in the attack on Chiang in 1943. And his four hundred concealed Communists included fellow travelers already attacked by HUAC and Kohlberg: Lillian Hell-man, Donald Ogden Stewart, E. C. Carter, Harriet Moore, Charlie Chaplin, Paul Draper.[28]

This "information" did not seem important enough to explain all the fuss. Agents were sent back to Budenz on April 5. This time Budenz elaborated on the role played by Field and Jaffe, describing Jaffe's demeanor at national committee meetings, adding detail to what he had told the bureau on March 27, but he could not remember that the Daily Worker had ever mentioned Lattimore.[29]

Hoover was still dissatisfied. He queried Ladd as to whether the new information about Lattimore was known when a memo on the Lattimore case was sent to the attorney general on March 22; Ladd said no, the first they heard of it was March 27, and Budenz had been "reinterviewed on April 3, 4, 5, and again on April 8." Budenz was to "endeavor to refresh his recollection concerning specific assignments of Owen Lattimore and will be interviewed again on April 10th."[30]

Hoover was unhappy with this answer. He wrote at the bottom of Ladd's report, "Why didn't we ask Budenz why he hadn't told us sooner? We have been in almost constant touch with him for months. Also, why haven't we taken the initiative in questioning him? It begins to look like another Chambers case where we didn't press for information."

At the April 10 interview Budenz provided a substantial part of his list of concealed Communists: 136 names. Scheidt cabled the same day that

BUDENZ STATED THAT THE INDIVIDUALS HE NAMED ARE CP MEMBERS AND NOT JUST SYMPATHIZERS. HE CALLS THEM CONCEALED COMMUNISTS BECAUSE THEY DON'T ADMIT THEIR MEMBERSHIP IN THE CP AND NEITHER HE NOR ANYONE ELSE CAN EXPOSE THEM SINCE THEY ARE PROTECTED BY THE LIBEL LAWS WHICH PARTY MEMBERS ARE ENCOURAGED TO TAKE ADVANTAGE OF AND FURTHER A SECTION OF THE REPUTABLE PRESS REFUSES TO ANALYZE THE RECORDS OF THESE INDIVIDUALS AND CHARGES PERSONS ACCUSING THEM OF BEING COMMUNISTS OF FINDING THEM GUILTY BY ASSOCIATION. BUDENZ WILL NOT BE AVAILABLE DURING THE NEXT WEEK SINCE HE IS ON A SPEAKING TOUR THROUGH THE MIDWEST .[31]

Surprisingly, Scheidt's cable did not include the latest Budenz "reflections" about Lattimore. One of the New York supervisors remedied this oversight in a telephone call to Duty Officer Hennrich at 9:20 P.M. Hennrich promptly wrote a memo to Belmont, who was now at headquarters in Washington. Budenz's "further reflections" were that Lattimore spearheaded the attack against Chiang Kai-shek in 1942. "Budenz recalled that the magazine 'Pacific Affairs' of the IPR carried an article attacking Chiang Kai-shek before it was officially known that the line was to change concerning Chiang Kai-shek from a policy of passive friendship to hostility. Budenz recalled that Field reported to the Political Committee that Lattimore had information that the line was changed."[32]

Since there was no such article in Pacific Affairs , Budenz later had to correct his claim. The article attacking Chiang was by T. A. Bisson, and it appeared in Far Eastern Survey , with which Lattimore had nothing to do. Then there was a new absurdity in the report from New York: "Budenz stated that up until the Hitler-Stalin Pact the Party made a practice of furnishing all members of the National Committee with onion skin copies of the minutes of the Political Committee meetings. He recalled reading reports by Field in the minutes and Lattimore was referred to as either 'L' or 'XL.' He stated that names were never mentioned in these reports, and that individuals were referred to by symbols. These reports had to be destroyed, or returned to a responsible official."[33]

By the time he got to the Tydings committee, Budenz had elaborated this to claim that the onionskin reports had to be torn up and flushed down the toilet; burning wasn't good enough, since it left ashes. No on-

ionskin reports ever showed up, and no other Communist or former Communist corroborated their existence. And nobody but Budenz ever claimed to have seen Lattimore referred to as "L" or "XL." Budenz's imagination was working overtime.

By the second week of April the FBI was engaged in that characteristic bureaucratic sport of damage control. It was not enough that Budenz was now telling them his new reflections about Lattimore; McCarthy, with his promise of a "secret witness" and the leaked knowledge that it was Budenz, had "captured" Budenz in the eyes of the press and attentive public. The FBI had to get Budenz back under control. Further, they had to explain their failure to extract from Budenz any information about one of their major cases despite an estimated three thousand hours of interrogation.

Assistant Attorney General Peyton Ford was pressing the bureau on this. Ford talked to Lou Nichols on April 11, saying Senator Tydings was now "out on a limb"; the bureau had better prepare a memorandum on Budenz's knowledge of Lattimore and when the bureau had obtained this information. If Budenz did testify, Ford said, the attorney general should know the background.[34] Hoover had such a memorandum in Attorney General McGrath's hands within hours:

[In regard to Ford's inquiry] you are advised that the Bureau has conducted exhaustive interviews with Budenz over an extended period of time dating back to his initial break with the Communist Party at a time when he was in seclusion at Notre Dame University.

Since that time we have had occasion to interview him off and on at periodical intervals. He has always been most cooperative and helpful, however, there was no occasion to direct specific inquiry to him pertaining to Owen Lattimore until recently. It would appear that had information occurred to him pertaining to Lattimore that he certainly would have mentioned it since he was interviewed, for example, on April 22, 1948, regarding ——— and in connection with the Amerasia case. There was no reason to believe that Budenz knew Lattimore or would have knowledge of espionage activities. As a matter of fact, when Budenz was interviewed on March 27, 1950, he specifically stated that he did not know Lattimore personally. He then furnished certain information which he has added to on an almost day to day basis since that time.[35]

Hoover's growing disillusionment with Budenz eventually resulted in outright skepticism. But the working-level agents were way ahead of Hoover. The New York agents, whipped into a frenzy of activity by Bud-

enz's sudden discovery of Lattimore, called in a crew over the weekend of April 8-9 to search their transcripts of Budenz interviews.[36] This review was completed late in the day April 10. Agent W. M. Whelan telephoned bureau headquarters at 2:00 A.M. April 11 with the results: Budenz had never mentioned Lattimore.

Whelan was caustic. He reviewed the various times Budenz had been grilled about IPR, about Amerasia , and about his Collier's article and had never even hinted that he had anything on Lattimore. Whelan concluded that when Budenz was interviewed about Lattimore on March 27, 1950, he had furnished a "rationalization" of the "alleged" part played by Lattimore in painting the Chinese Communists as mere agrarian reformers; however, Budenz had furnished "no information or even allegations which tend to prove" McCarthy's claim that Lattimore was a Communist agent.[37]

Whelan's conclusions caught the eye of Belmont as soon as he got to the office that morning. He telephoned New York, but Whelan had gone home after his 2:00 A.M. report to Washington. Belmont spoke to an agent whose name is denied, demanding another immediate interview of Budenz to find out why he had held out on the Lattimore information so long and to impress on him the importance of having a good answer.[38]

New York had bad news: Budenz had already left for his Michigan speaking tour. Belmont then set out, with some asperity, several tasks for the New York office: check with Mrs. Budenz, get Louis's itinerary, find out if he had yet received a subpoena from Tydings, and get his day and time of arrival back in New York. An agent was to meet him at the plane and get answers .[39]

New York must have gotten the overworked Whelan out of bed, for Whelan called Belmont later on April 11 to report Budenz's itinerary and arrival time in New York on Saturday April 15 and to give the news that Ed Morgan of the Tydings committee had wanted to serve a subpoena on Budenz the day before, but Budenz had already left. Belmont reported this conversation to Ladd:

ASAC Whelan was advised that in the event no instructions are received to the contrary, Agent ——— should interview Budenz immediately upon his return along the lines indicated above, the purpose being to find out why Budenz didn't furnish us this information regarding Lattimore before when he had full opportunity to do so . . . . I think, during the contemplated interview, Agent ——— can plant the seed in Budenz' mind that he was fully cognizant that the FBI was keenly interested in any information concerning Communism or espionage, that he had full opportunity to furnish information concerning

Lattimore during questions by agents relating to associated matters such as the IPR ——— and that he, Budenz, was negligent in not furnishing the information to the FBI concerning Lattimore prior to March 27, 1950. Agent ——— was instructed by me to plant this idea with Budenz during the contemplated interview if it could be done gracefully.[40]

At midnight Scheidt cabled Washington. Mrs. Budenz had called. Louis had telephoned her and said he had accepted a subpoena by telephone from Tydings to testify April 20.[41]

At 7:00 P.M. on the twelfth Scheidt cabled Washington again. He had talked to Budenz by telephone in Michigan. Budenz was now backtracking on several things, including his knowledge of Andrew Roth and his statement that Lattimore was to spearhead the attack on Chiang. But the vital matter was this: "BUDENZ ALSO WANTED TO BE ASSURED THAT THE INFO WHICH HE WAS FURNISHING THE BUREAU WOULD NOT BE MADE AVAILABLE TO SOME PERSON WHO COULD CROSS EXAMINE HIM DURING THE SENATE COMMITTEE HEARING. HE WAS GIVEN THIS ASSURANCE. BUDENZ STATED THAT HE SAW ALFRED KOHLBERG FOR A FEW MINUTES DURING THE PAST WEEKEND, AND KOHLBERG ACTED AS HIS LIAISON MAN WITH MC CARTHY ."[42]

When Hoover saw this cable the next day, he exploded. "Did NY Office ask him why he hadn't given us the Lattimore material sooner? If not, why not? It was a perfect opening." Scheldt answered that the telephone line was not secure, so he did not ask.[43]

Tension at the bureau was now high. Belmont spent several hours on April 14 composing a letter to Ladd answering Hoover's complaint that the bureau had not sufficiently grilled Budenz. Belmont reviewed the bureau's contacts with Budenz exhaustively, noting that "Budenz has been cooperative and thoroughly respects the Bureau. His attitude is good. However, I do not feel that we are in a position to sit him down as we did Chambers and interview him for three months to drain him dry. He has many commitments and we do not have the hold on him that we had on Chambers." Belmont had several recommendations for getting Budenz to confess his error.[44]

Hoover still wasn't satisfied. At the bottom of Belmont's report he wrote, "O. K. but don't ponder about it too long. All very good if it is kept alive. We missed the boat with Chambers & now Budenz. We can't miss many more without getting strong public castigation."

At 9:15 P.M. Saturday, April 15, Budenz was met at LaGuardia Airport by the two agents who had been interviewing him. They were armed with half a dozen cables from Hoover telling them to ask Budenz about several

specific charges he had made about Lattimore that didn't check out; but mostly they were to find out why he hadn't leveled with them.

The agents got an earful. Scheidt cabled headquarters six hours later, at 3: 15 the next morning: "BUDENZ . . . SAID HE NEVER MENTIONED WHAT HE KNEW ABOUT LATFIMORE BECAUSE HIS INFORMATION WAS FLIMSY. IT WAS NOT LEGAL AND HE HAD DEVOTED MOST OF HIS TIME TO FURNISHING LEGAL EVIDENCE TO THE FBI. HE KNOWS HE SHOULD HAVE FURNISHED THE INFORMATION BUT STATES IT WAS HUMANLY IMPOSSIBLE . . . IN THE TIME HE HAD AVAILABLE TO WORK WITH THE FBI ."[45]

So it was flimsy evidence that the high priest of anticommunism was about to pass on to a Senate committee, slandering a professor whom he had never met nor read, escalating the inquisition to an even higher pitch—and rescuing Joe McCarthy. Had the bureau been fair, rather than a cheerleader in the hysteria, it would have summarily scuttled Budenz as a Lattimore witness.

Instead, the bureau entered into a conspiracy with Budenz and the Department of Justice to prevent truth from emerging in the Tydings hearings. The bureau knew three things about Budenz's testimony: he thought it was flimsy, it was laughably inconsistent, and he was unwilling to face a cross-examiner who was prepared for him. Instead of informing Tydings, the committee staff, or McCarthy about the weaknesses of their next witness, Ladd telephoned Ford at Justice: "I told him that we had assured Budenz that this material would not be made available to the committee for cross examination purposes and that I hoped the Department was not furnishing it to the committee until after Budenz had testified." Ford said Justice would go along with this approach.[46] The Tydings hearings were not a criminal trial. Had they been, the FBI and the Department of Justice would have committed an obstruction of justice.

April was Budenz month at the FBI. Hundreds of memos, telephone calls, letters, telegrams, and conferences were devoted to getting Budenz under control. The speeches he made in Michigan caused further trauma; Hoover cabled New York on the nineteenth, asking them to check out five new claims Budenz made in Michigan that the bureau was not privy to. All of them turned out to be false: IPR offices were not located in the same building as the pro-Communist China Today , and Lattimore did not place a Communist elevator operator from Indonesia with OWI as a translator. Other claims Budenz made to the bureau in confidence, which were checked out with apparently negative results, are still classified.[47]

New York also continued its round-the-clock Budenz operation. Agents saw him every day between his return from Michigan on the fifteenth

and his departure on the nineteenth to testify in Washington. Scheidt was up all night the eighteenth, preparing an eight-page telegram to Washington reporting what they had learned from Budenz that evening; his telegram was flied at 5:12 A.M. on the nineteenth. Thomas Reeves heard from Charles Kersten that "agents grilled Budenz so intensely that when Kersten later visited him, he and his wife were in tears from the pressure."[48]

At one point Budenz was to prepare a statement for Tydings; he didn't have time to do it. It was with some relief that he boarded an American Airlines plane at 1:35 P.M. on April 19 for Washington; he would at least get a tension-free evening with his host, Fulton Sheen.[49] The next day was D day.

Lattimore and Fortas were of course unaware of the turmoil and bitterness inside the government. They did know that Budenz could be a serious threat. As Lattimore describes it in Ordeal By Slander , Fortas told him:

McCarthy is a long way out on a limb. The political pressures that are building up are terrific. The report that Budenz will testify against you has shaken everyone in Washington. It is my duty as your lawyer to warn you that the danger you face cannot possibly be exaggerated. It does not exclude the possibility of a straight frame-up, with perjured witnesses and perhaps even forged documents. You have a choice of two ways of facing this danger. You can either take it head on, and expose yourself to this danger; or you can make a qualified and carefully guarded statement which will reduce the chance of entrapment by fake evidence. As your lawyer I cannot make that choice for you. You have to make it yourself.[50]

Lattimore chose to take it head-on. He never regretted it.

Since Lattimore and Fortas did not know what Budenz would claim, there was little they could do to prepare for his testimony. One rumor had it that Budenz would claim that Fred Field had somehow implicated Lattimore in Party activities. Fortas talked to Field, who responded with a letter saying that if Budenz claimed that Field had told him anything at all about Lattimore, then Budenz was lying. Fortas also got an affidavit from Bella Dodd, a former Communist who had outranked Budenz in the Party, to the effect that in all her time as a Party activist she had never heard one word about Lattimore. And Brigadier General Elliot Thorpe, who had been head of counterintelligence and a rival of General Willoughby in MacArthur's Tokyo command, was persuaded to state the results of his investigations of Lattimore during the Pauley mission: Thorpe

said Lattimore was unquestionably a loyal American. He later told Tydings the same thing.[51]

One encouraging development buoyed Lattimore's spirits five days before Budenz's appearance at the Tydings hearings: he was asked to give the closing address to the fifty-fourth annual meeting of the American Academy of Political and Social Science in Philadelphia. This address made the front page of the Times ; Lattimore was quoted as recommending that the United States withdraw support from the Nationalist regime on Taiwan but not as yet recognize the People's Republic. He also thought the Nationalist raids against the mainland were dangerous since they might induce the People's Republic to call in the Russians to counter them. The academicians gave Lattimore enthusiastic applause.[52]

On April 20, 1950, when Budenz appeared before the Tydings committee, the audience was quite different from the scholars Lattimore had faced. Clergy in black cloth were much in evidence; so were members of the Daughters of the American Revolution, in Washington for a convention. To this audience, Budenz was a dragon slayer.

Nonetheless, Budenz's task that day was harder than the one he had faced in the Foley Square trials of the top Communist leaders in 1949. At Foley Square he needed only to describe the extent to which admitted Party functionaries were manipulated by Soviet emissaries. He knew the defendants from working with them; he had firsthand knowledge, so there was no doubt about his standing as a witness. At the Tydings hearings, in contrast, he was making charges against a man he had never met, and his claims about Lattimore, as he had admitted to Matthews, were hearsay.

But the aura of the Party insider was still useful. Budenz began by reviewing his testimony about the Communist party as a conspiracy, not a legitimate party at all but an arm of the international Communist movement.[53] This testimony was irrelevant to the Tydings committee's concerns about whether there were Communists in the State Department—but it was vital to Budenz's image as an informer. So was his public stance as a reluctant witness. Three times during his testimony he emphasized that he came only under subpoena, unwillingly, sacrificing his time and privacy for the greater good of the nation. Thus, he began with an outrageous lie, and it was all downhill from there.

Since his biggest hurdle was overcoming the hearsay handicap, he used a rhetorical technique based on the theme of editorial omniscience. The Daily Worker , which he had edited, was the Party organ for informing the faithful not only what they were to believe but who was authoritative in telling them what to believe. As editor, Budenz said, he had had

to understand what was occurring within the Communist movement. I also received direct instructions, well, almost hourly, as a matter of fact, but certainly every day, from the liaison officer connected with the Politburo. We had a liaison officer appointed who gave me instructions from day to day and in addition to that kept refreshing me on a list of about a thousand names which I was compelled to keep in my mind as to their various attitudes toward the party, the various shifts and changes, whether a man had turned traitor or whether he had not, and things of that sort. This list was not put down in writing because of the fact that it might be disclosed, consequently I was compelled to keep it in my mind, and this representative of the political bureau, the Politburo, kept refreshing my mind on this list of names.[54]

Budenz had developed this claim of editorial omniscience to overcome the handicap first revealed in 1945 to the FBI's Pat Coyne during the South Bend interviews: that because he had not been trained in Moscow, Party leaders did not fully trust or confide in him. As the years went by, Budenz found that a plausible answer to skeptical bureau agents asking him "How do you know this?" was "I had to know it in my capacity as editor." The editorial omniscience ploy did not always work; in some matters, such as Budenz's claim that the IPR and China Today offices were in the same building, the FBI could force him to recant by independent investigation.

In the area of naming names, however, the tactic worked like a charm. Who could disprove the contention that Fred Field had reported to the Politburo that Lattimore had carried out the assignment to "change the line" on Chiang Kai-shek? Field could deny it endlessly, but Communists lie. Lattimore's denial was self-serving. Jack Stachel, Earl Browder, and other Politburo members either wouldn't talk or would lie. It was a foolproof scheme.

Well, not quite foolproof. If the government was prepared to spend several million dollars investigating Budenz's accusations against one individual, as it did with Lattimore, Budenz could be refuted. There had to be, if Budenz was telling the truth about Lattimore, some individual somewhere who had left the Party and who would testify that he or she had taken orders from Lattimore, or had written a piece to carry out the new policy, or knew firsthand that Lattimore had directed this campaign. There had to be some evidence that Lattimore had "been of assistance" in the Amerasia case. There was no such confirmation, anywhere in the world, of any of Budenz's charges against Lattimore, and both FBI and Justice eventually gave up hunting for it.

Unfortunately, not all the four hundred concealed Communists fingered by Budenz were cleared by massive investigations. Some of them may have been secret Communists, but who knows what damage was done to those who were not? At the very least, their FBI and passport files bear the stain of Budenz's accusations.[55]

Apparently nobody laughed when Budenz told Tydings that he kept in his head a list of a thousand names as a requirement of his editorial job. Nobody from the FBI warned Tydings committee members that James Glasser, managing editor of the Daily Worker when Budenz was labor editor and in 1950 a former Communist, told the bureau that "based upon his knowledge of the functions of the managing editor of the Daily Worker , BUDENZ was obviously fabricating 'smears' against LATTIMORE and others, in his Senate Sub-Committee testimony. He added that although he does not know anything regarding LATTIMORE , he would wholly discount BUDENZ'S remarks as those emanating from a psychopathic liar."[56]

Nor did the bureau publicize the fact that when Budenz's recollections of "concealed Communists" ran out well short of the promised four hundred names, Budenz "refreshed his memory" from lists of officers and sponsors of left-wing organizations such as the American Artists Congress, Artists Front to Win the Peace, Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences and Professions, Newspaper Guild of New York, People's Radio Foundation, and Win the Peace Conference.[57]

"Editorial omniscience" was by itself insufficient to ensure Budenz's credibility. He used a companion rhetorical ploy extensively before Tydings: his hearsay was better than garden variety hearsay: it was official . In his first day of testimony Budenz described what he claimed he was told by Party leaders as "official" twenty-three times. Phrases like "the instructions and directions I received officially," "according to the official reports made to me," "it was officially reported that Mr. Lattimore had received word," "official documents," and so forth appear on almost every page of the transcript. This tactic may not have convinced all of his listeners, but coupled with his claim that Communists never lie to each other, only to those outside the Party, it got him through the pallid questioning of the committee members when they heard Budenz in executive session five days after the public hearing.

Not surprisingly, Budenz decided against reinforcing his hearsay testimony by citing the anti-Lattimore statements of his good friend Alfred Kohlberg. Rather, his corroboration was the Columbia article of September 1949 by James F. Kearney, whom Budenz described as "an expert on

the Far East." Budenz quoted Kearney's article to Tydings: "There are those who believe, though, that no Americans deserve more credit for the Russian triumph in the Sino-American disaster than Owen Lattimore and a small group of his followers."[58] Senator Theodore Green of Rhode Island was skeptical:

Green : Do you know where Father Kearney got his information?

Budenz : I do not know, sir.

Green : Did he tell you, or did he not, that he got it from Alfred Kohlberg, of New York?

Budenz : No, sir.[59]

Kohlberg was, however, Kearney's main source. Not until October 1950 did the FBI check out the Kohlberg-Kearney connection, to the disgrace of both.

Budenz made five charges before Tydings. (1) At a Politburo meeting in 1937 Field and Browder commended Lattimore for placing the works of Communist writers in IPR publications. (2) At another meeting in 1937 Field and Browder decided that Lattimore should be given general direction of a campaign to organize writers on China to portray the Chinese Communists as not Communists at all, but as agrarian reformers. (3) In 1943, at a similar meeting, "it was officially reported that Mr. Lattimore, through Mr. Field, had received word from the apparatus that there was to be a change of line on Chiang Kai-shek." (4) In 1944 Jack Stachel told Budenz to "consider Owen Lattimore a Communist." (5) In 1945 Stachel told Budenz that Lattimore "had been of service in the Amerasia case."[60] None of these things ever happened.

The committee treated Budenz gingerly. The Democrats (Tydings, Green, and Brien McMahon) were more skeptical than were the Republicans (Lodge and Hickenlooper). The press was skeptical, but following journalistic standards of the day, Budenz's assertions, like McCarthy's, were news and were reported uncritically.[61] Even the New York Times , no fan of McCarthy, carried Arthur Krock's gullible column the Sunday after Budenz's testimony under the headline, "Capital Is Disturbed by Budenz Testimony. Even Critics of McCarthy's Methods Now Take Anxious View of New Development in Inquiry."[62] Budenz had fulfilled his role; he had rescued McCarthy.

But out of public view, challenges to Budenz's credibility continued to mount. On April 26 an important Pennsylvania ex-Communist, whose name is still denied by the FBI, told agents that

he [had been] expelled from the Communist Party———but had attended numerous Party meetings in New York City during the preceding twenty years, where Communist Party policy was discussed, but he could not recall that OWEN LATTIMORE'S name was ever mentioned as having any connection with the Communist Party. ——— that he had been following the LATTIMORE case in the papers and was of the opinion that LATTIMORE was not a Communist because the Communist Party would never allow LATTIMORE to depart from the Party line and write articles which would be critical of Russia. ——— that he knows LOUIS BUDENZ slightly and believes him to be dishonest and a psychiatric case.[63]

This testimony never saw the light of day.

On April 28, 1950, Budenz was grandstanding again. In a speech at Peekskill, New York, he stated that he knew "who arranged the theft of the Amerasia papers. . . . Budenz said the investigation of the Amerasia case and charges that Owen Lattimore is a Communist should be closely linked and that the Lattimore and Amerasia cases are 'both interlocked and cannot be separated. If fully investigated the cases will provide one of the greatest scandals that American political history has ever witnessed.'"[64] The FBI discovered that Budenz had, as usual, no "actual facts" to support this charge.

As the summer wore on, the FBI discovered that Budenz had few "actual facts" about anything. On May 25, reporting a recent interview designed to clarify what Lattimore had actually done about changing the party line on Chiang Kai-shek, the New York office told headquarters that Budenz "was unable to state" whether Lattimore knew about this change in advance, nor did he know whether Lattimore was responsible for publication of the Bisson article. A New York FBI report of July 18 reveals Budenz soaring far into fantasyland. In large Russian cities, he said, "nearly every child is trained in the art of paratrooping." Why? Because Stalin had no regard for the lives of his citizens and was planning "large scale attacks of suicide paratroopers carrying bombs," like the Japanese kamikaze pilots who gave their all in the Pacific war.[65]

For all his appeal to the Catholic faithful, Budenz was beginning to lose even some of his church supporters. In a memo to Hoover May 1, 1950, Ladd reported:

Mr. John Steelman, the Assistant to the President, mentioned to Mr. Roach this morning while discussing other matters that he was becoming highly suspicious of the activities of Louis Budenz. He stated that the activities of Budenz had also aroused the suspicions of other persons, whom he indicated were attached to Catholic University here in

Washington. His contact at Catholic University apparently gave Steel-man the impression that they had a "hot potato" on their hands and did not know how to get rid of him. The undercurrent of feeling seems to be, according to Mr. Steelman, that they are sceptical of Budenz's so-called return to Catholicism. They view him as still a "good Communist." Mr. Steelman commented that some Church leaders, (names not mentioned) have told him that Budenz's testimony before the Tydings Committee certainly did not help the prestige of the Catholic Church, and although he, Steelman, has no information to prove or disprove that Budenz is still a Communist, he stated that he certainly has his suspicions. He commented, "I hope J. Edgar is keeping an eye on him."[66]

Hoover noted laconically, "Keep possibility in mind."

1.

Owen and Eleanor Lattimore at their wedding, Peking, March 4, 1926.

Courtesy of David Lattimore.

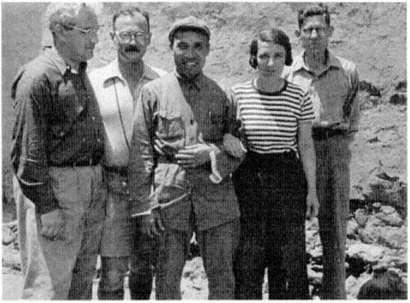

2.

Philip Jaffe, Lattimore, Chu Teh, Agnes Jaffe, and Thomas Bisson. Yenan,

June 1937. Courtesy of David Lattimore.

3.

Lattimore and Chiang Kai-shek, Chungking, September 1941. Courtesy of

David Lattimore.

4.

Henry Wallace, Lattimore, John Carter Vincent, and John Hazard, China,

June 1944. Courtesy of David Lattimore.

5.

Vilhjalmur and Evelyn Stefansson. Courtesy of Evelyn Stefansson Nef.

6.

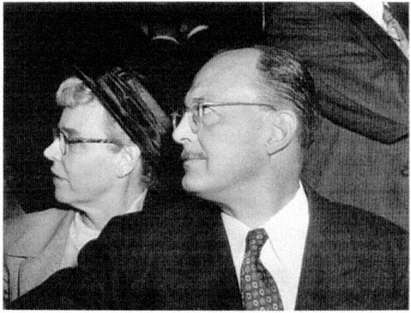

Owen and Eleanor Lattimore at Tydings committee hearings, April 20, 1950.

Courtesy of Acme Photo.

7.

William D. and Suki Rogers, summer 1953. Courtesy of Suki Rogers.

8.

The Dilowa Hutukhtu, about 1958.

Courtesy of David Lattimore.

9.

Lattimore in morning dress on his way to interpret for Queen Elizabeth II,

November 14, 1963. Courtesy of Diana MacLeish.

10.

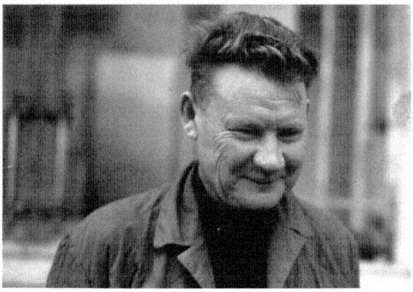

A. P. Okladnikov, Ulan Bator, summer 1964. Courtesy of David Lattimore.

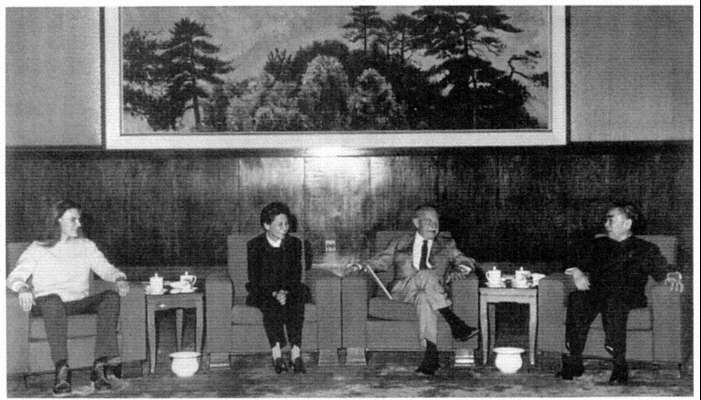

11.

Michael Lattimore, Fujiko Isono, Lattimore, and Chou En-lai in the Great Hall of the People, Peking, October 1972. Courtesy of

David Lattimore.

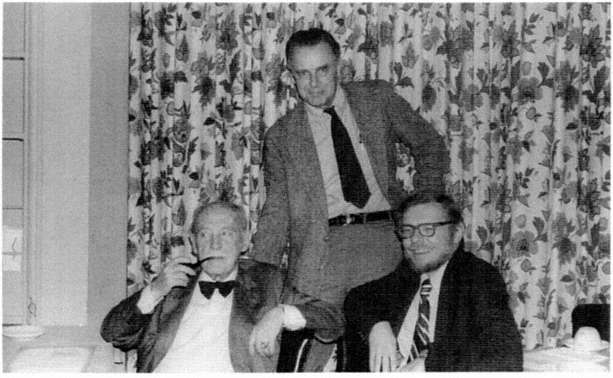

12.

Lattimore, Robert P. Newman, and Dean Alec Stewart, University of Pittsburgh, March 19, 1979. Courtesy of

Dewey Chester.

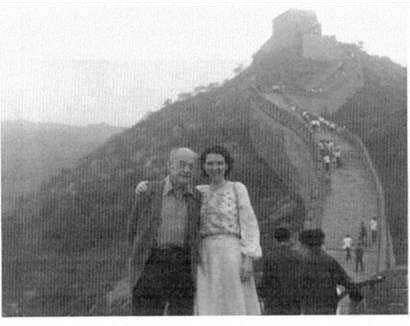

13.

Lattimore and Maria Lattimore on the Great Wall, summer 1981. Courtesy

of David Lattimore.

14.

Premier Tsedenbal of the Mongolian People's Republic and Lattimore, Ulan

Bator, summer 1981. Courtesy of David Lattimore.