Preferred Citation: Pinch, William R. Peasants and Monks in British India. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft22900465/

| Peasants and Monks in British IndiaWilliam R. PinchUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · London© 1996 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Pinch, William R. Peasants and Monks in British India. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft22900465/

A Note on Translation and Transliteration

Unless otherwise noted, all translations are my own. I have endeavored to transliterate Hindi terms as they sound, without the use of diacritical marks. The main difference readers may notice is that the final ‘a’ employed in the transliteration of Sanskrit (which is silent in Hindi) is often dropped. The general exception to this rule is with words that are familiar in English usage, such as karma, dharma, varna, Vaishnava, Shaiva, etc.

Acknowledgments

The research and writing of this work has occurred on three continents and in eight cities, beginning in 1986 and ending in 1995. Along the way I piled up many professional debts, but none more substantial than that owed to Walter Hauser, save for whose selfless guidance over the course of the 1980s I would not have had the great good fortune to become a historian of India.

The book itself benefited from the discerning eyes of teachers, colleagues, editors, and others. In addition to Walter Hauser, these include Richard B. Barnett, William B. Taylor, R. S. Khare, Tessa Bartholomeusz, Christopher V. Hill, Rosemary Hauser, Philip Lutgendorf, Romila Thapar, Lynne Withey, Barbara Howell, Bruce Masters, Ann Wightman, Richard Elphick, Jennifer Saines, two anonymous readers for the University of California Press, and Mark Pentecost, copy editor for the Press. I am grateful for their many contributions, textual and otherwise, whether in the doctoral thesis stage, while transforming the thesis into a book, or while preparing the manuscript for publication. Portions of chapters were presented at public lectures and seminars. These occurred at the University of Virginia, the University of California at Berkeley, North Carolina State University, Wesleyan University, the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, and the University of Pennsylvania; related papers were also presented at regional and national meetings of the Association for Asian Studies. My thanks to those who made these occasions possible and to those who attended and offered their reactions.

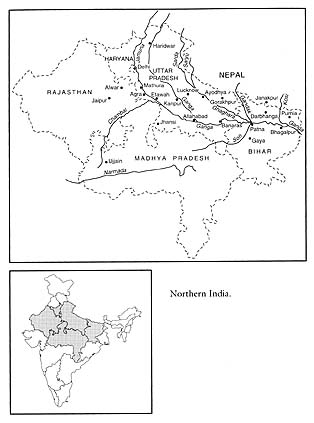

For their help during the research and writing, I wish to acknowledge the following: Shaibal Gupta and the A. N. Sinha Institute for Social Studies in Patna, for providing the necessary institutional affiliation; Surendra Gopal and Hetukar Jha of Patna University for their kind hospitality, and the latter in particular for allowing me to consult his collection of the Patna District Village Notes during the untimely closure of the local record room; my research assistants, S. K. Pathak, Ram Prasad Shrivastav, and Ejaz Hussain; Dr. A. P. and Mrs. S. P. Bakshi, for welcoming us to Patna; Mira and Suresh Prasad Shrivastava, our hosts in Arrah; Sukirti Sahay, for assisting in the translation of Bihari passages; K. S. Chalapati Rao and Bhupesh Garg of the Institute for the Study of Industrial Development, New Delhi, for introducing me to the Institute’s digital map-making technology and allowing me to construct a base map for the present work; Philip McEldowney of Virginia’s Alderman Library and Stephen Lebergott of Wesleyan’s Olin Library, for providing books and references at short notice; the U.S. Library of Congress foreign book acquisitions project, and of course the American taxpayers who fund it and, on occasion, me. I am particularly indebted to Kailash Chandra Jha, formerly of the U.S. Library of Congress in New Delhi, now with the American Embassy, for his invaluable help over the past thirteen years.

The research was funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Education, with additional research and writing support from the Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned Societies, for all of which I am grateful. Thanks are owed as well to Dr. Uma Das Gupta, regional director of the U.S. Educational Foundation in India, who did so much to make our stay in Calcutta both comfortable and enjoyable, and to Dr. Pradeep Mehendiratta of the American Institute of Indian Studies for facilitating the complex logistics of research approval from the Government of India. I wish to acknowledge the support received from the directors and staff of the Bihar District Record Rooms (in Gaya, Patna, and Arrah), the Bihar State Archives in Patna, the National Archives in New Delhi, the National Library in Calcutta, and the Oriental and India Office Collection of the British Library in London. Of course, none of the above-named individuals or institutions are in any way responsible for errors, omissions, or misinterpretations herein.

Finally, family and friends have sustained me over the past decade of research and writing. I can only offer in return my love and gratitude, and pray that Rosemary and Walter, Kailash and Abha and Sona and Rumki, Pete and Gary and Sheila and Sarah, Quatro and Joan and Collin, Helen and George, Jennifer and Pearse, and my parents will forgive my sentimental need to single them out in particular.

Vijay Pinch

London

13 July, 1995

Maps

Introduction: Peasants, Monks, and Indian History

According to strict social science definitions, colonial India was a peasant society. By far the vast majority of the population of the subcontinent lived in villages, and well over half the working population was engaged directly in agriculture. These villages were not isolated communities: the urban population was small by comparison but substantial, and urban magnates maintained important social, economic, and political ties to the countryside to secure the steady stream of agricultural goods that sustained city life. The state was organized into territorial provinces that transcended lines of caste and clan and whose complex bureaucratic dimensions reflected the agrarian revenue potential. Clear cultural, social, economic, and political distinctions could be and were made between town and country. Most importantly, the typical unit of production was the family household, which may or may not have owned the land upon which it worked but, regardless, directed its combined labor to the cultivation of crops.[1]

Colonial India also had a history of significant religious variety. Indeed, few visitors to the subcontinent over the last twenty-five centuries—from Alexander to al-Biruni to Attenborough—have failed to make note of this fact.[2] Fewer still have failed to remark upon the vast numbers of holy men who wander the subcontinent, reside in its villages, towns, and cities (often near shrines) and throng its sacred places. These holy men, known generically as sadhus (Hindu) and fakirs (Muslim), can be described as monks inasmuch as they belong to one of many Indian monastic traditions of social detachment and spiritual discipline. As in the European tradition, however, monasticism in India encompasses a wide variety of religious experience. While frequent pilgrimage, alms, and tests of physical endurance are and have long been important aspects of the lives of many Indian monks, Indian monasticism cannot be reduced to itinerancy, begging, and asceticism.[3] Many monks are and have long been devoted to careful study and spiritual contemplation, conducted entirely within the walls of a sanctuary in an attempt to create a paradise on earth. Still others were expert in the arts and science of warfare.[4] Though the institutionalized forms of charity—such as the creation of hospitals—common to western monasticism have not been nearly so prominent in India, many Indian monks were respected as able healers,[5] and service (seva) remains a central ideal of most Indian religious traditions. Indeed, the ritual removal of Indian monks from “worldly” concerns has long presaged (and was preparatory to) their active engagement in the world, whether conducted from a religious center or as part of an itinerant or soldiering lifestyle. Finally, Indian monks come from all sections of society, including the peasantry, though the degree to which monastic orders recruited from the ranks of the low-born in rural society (whether peasants or artisans) varied. However, at least one major monastic community—the Ramanandis, who look to Ramanand of fourteenth-century Banaras for religious inspiration—has long been dedicated to the recruitment of novices (both male and, to a lesser degree, female) from the entire social spectrum. Understanding how this Ramanandi recruitment philosophy has worked in historical practice, particularly during the colonial era, is one of the aims of this book.

Indian peasants and monks did not live in social and religious isolation, from the world or from each other. Indeed, the lives of peasants and monks in colonial India were (and are) intricately intertwined: monks depended on peasants for agrarian labor, material sustenance, and monastic recruitment; peasants looked to monks for spiritual guidance, religious knowledge, and ideological leadership. Both expressed increasing concern in the colonial era with questions of religious identity and social status, in part because those questions had immediate and long-range political and economic ramifications. Peasants and monks addressed those questions by advocating both attacks on and manipulations of social hierarchy, that is, caste. The story of those attacks and manipulations, and their implications for colonial India, make up a large part of the history described in this book. However, this history also includes significant religious and cultural change, which should not be ignored.[6] Furthermore, the world that peasants and monks lived in, and assisted in creating, came to occupy a central place in the history of colonial and nationalist India. That world is with us still, nearly a half-century since independence from British rule, and, it can be argued, contributes to the ongoing crisis of religion and the state in north India.

This book, then, is a history of the ways in which religion intersected with dramatic political and social change in colonial India. It will come as no surprise to social historians that religion has been drawn upon to express material complaint in times of rural social, political, and economic stress;[7] a corollary, in modern south Asia at least, is that monks have readily assumed the burdens of peasant advocacy.[8] But, despite the importance of radical monks who led rural rebellions, most of the social history that has described them does not explain the role of religion, or the exceptionally religious, in peasant society; rather, it merely comments upon the fact. This is as true for colonial India as it is for late antique Rome. Peter Brown has observed that social historians of the late Roman empire have “tended to stress the spectacular occasions on which the holy man intervened to lighten the lot of the humble and oppressed: his open-handed charity, his courageous action as the spokesman of popular grievances—these have been held sufficient to explain the role of the holy man.” But, Brown adds,

such a view sees too little of the life of the holy man.…Dramatic interventions of holy men in the high politics of the Empire were long remembered. But they illustrate the prestige that the holy man had already gained, they do not explain it. They were rather like the cashing of a big cheque on a reputation; and, like all forms of power in late Roman society, this reputation was built up by hard, unobtrusive (and so, for us, partly obscure) work among those who needed constant and unspectacular ministrations.[9]

Certainly there are plenty of cases of peasant grievance expressed in religious language in Indian history; likewise there is no shortage of peasant movements led by holy men. Indeed, some of those grievances and movements find their way into this book. But I would be telling only half the story were I to confine myself to such matters, because the long process of change that allowed monks to lead peasant movements in Gangetic India under colonial rule was as much ideological, cultural, and religious as it was material, economic, and social. The history of peasants and monks in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in India includes the growth and transformation of a conscious “Hindu” historical discourse, which itself was the result of a prolonged process of religious institutionalization.[10] That history is also the story of the coming of age of the “middle peasant”—the tenant farmer and small proprietor, clinging tenaciously to the margin of property—however one chooses to describe his politics and understand his fate.

A main purpose of this work, consequently, is to explore directly and in depth the religion that aids in defining the world of the Gangetic peasantry in colonial India. This involves broadening the working definitions of religion beyond the personal and private to include much of what is normatively considered political, social, and economic; it also involves understanding peasants in terms not only of what they do—i.e., their labor, behavior, riots, and occasional rebellions—but also of what they believe and think and say and write. I hope that by so doing we gain a better sense of the mental worlds that produced and gave meaning to action in colonial north India, whether that action was violent or gentle, religious, social, economic or political.[11] This recourse to culture and, ultimately, religion should not be seen as an abandonment of social history as such, but as a recognition that while social history has enabled us to ask important questions, it has not provided the tools with which to craft satisfactory answers.

| • | • | • |

Religion, Politics, and History in India

India has long been represented as a place of timeless peasants and ageless monks, and not just by an intellectual elite that is today labeled “Orientalist.”[12] To the British administrator, the peasant represented an India that was noble, honest, and good. The monk, by contrast, represented an Orient that was mysterious, unpredictable, and dangerous. In ideological terms, this was a necessary juxtaposition: the colonial official, steeped in both utilitarian philosophies of rule and romantic notions of benevolent despotism, saw himself as the protector of the common man—the peasant—against the extortions of idle, urban elites and the corruptions of corrosive superstition.[13] Thus the picture of the hardy peasant and his negative imprint manifest in the nefarious monk were central to the strategic—and for the most part unconscious—posturings of British colonial officials on the right side of history.

But the image of India as peasant and monk writ large was not confined to European imaginations: Mohandas K. Gandhi’s political technique played on British idealizations of the peasantry and monasticism and of India generally. From the nationalist perspective, the ability of the Indian National Congress to control the peasants and monks of India was of less importance than the British perception that Congress possessed the ability to do so. And Gandhi, who represented both humble peasant and simple monk, seemed to speak for India’s masses, whether or not he could control them. The peasant-monk ethos defined Gandhi’s very existence: his simple garb, his spare meals, his ashram (sanctuary), his celibacy, his daily routine of meditation and constructive work, his nonviolence—all evoked ideals of religious asceticism and rural simplicity. This ethos, and the relentless dedication to truth (satyagraha) that sustained it, afforded Gandhi substantial moral influence, for a time, among peasants and monks as mahatma, great soul.

Gandhi as mahatma was both more and less than an imagined miracle worker, a figment of rural imaginations run rampant.[14] Because Gandhi seemed able to speak to India’s monks, the British were soon convinced that he could speak for India’s peasants. This conviction emerges with crystal clarity in the official reaction to the fact that hundreds of monks attended the 1920 Indian National Congress meeting in Nagpur, anxious to see and hear the man who was bringing mass politics to the national level and to involve themselves in his—and in many ways their own—political idiom. An observer dispatched to report on the Nagpur proceedings to the government noted in his account that “an association of the most powerful sadhus called Nagas [soldier monks] had been formed at Nagpur” and that “a meeting of over a hundred of these sadhus had been held in the Congress Camp and they had decided to undertake non-cooperation propaganda.”[15] Great significance was attached to this act, since it was maintained that these “sadhus visited most of the villages and towns and the masses had a high regard for them, and thought a great deal of their instructions and preachings. When these Nagas took up non-cooperation, the scheme would spread like wild fire among the masses of India and eventually Government would be unable to control 33 crores of people and would have to give Swaraj.”[16] The official report also noted that Gandhi personally thanked the sadhus for their support and urged them to “visit the vicinities of cantonments and military stations and explain to the native soldiers the advisability of giving up their employments”—thus recalling the fears of sepoy disloyalty that still resonated after the rebellion of 1857. After the Nagpur Congress, the intelligence branch of government would become increasingly concerned with the activity of “political sadhus.”[17]

Colonial and nationalist idealizations of peasants and monks were reductive, one-dimensional, and misleading: most peasants and monks in British India were not immediately concerned with the national implications of colonial rule, let alone nationalist politics—despite Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s (1838–1894) late nineteenth-century fictional representations of patriotic sadhus sprung organically from the soil of Bengal and ranged against oppressive, foreign rule; despite Gandhi’s desire to attract the participation of peasants and monks in a mass-based nationalism; and despite Nehru’s efforts to lecture peasants on the meaning of Bharat Mata—mother India—in the 1930s.[18] But peasants and monks were not unconcerned with politics and their place in an Indian nation. Rather, their politics were locally defined, their concept of nation (as country) deeply embedded in Indian social and cultural history.[19] Though their brief engagement in the nationalist politics of India drew them for the first time into the narrow beam of the historian’s searchlight, it was not the first time peasants and monks had combined to bring about social and ideological change.

The peasants and monks who populate the history of Gangetic India were historiographically complex, because they could think and speak for themselves; indeed, their thoughts and opinions are the basis of this study. Peasants and monks in British India acted and spoke in ways that seemed strangely out of character for people normally (and normatively) engaged in agricultural labor and the disciplined pursuit of spiritual truth. Completely independent of nationalism, many peasants of Gangetic India in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries began to voice loud objections to the servile status that society and the state ascribed to those who worked the soil. It gradually became clear that many of those peasants thought of themselves not as cosmically created servants (shudra) devoid of any history, but as the descendants of divine warrior clans (kshatriya) firmly rooted in the Indian past. The dimensions of those assertions, the discourses drawn upon to articulate them, and the elite reaction to them reveal a wealth of information not only about peasant culture but of popular ideological change during the colonial era.

Monks, likewise, had strong opinions that informed and were informed by the goings-on in Gangetic society. They were willing and able (indeed expected) to leave behind the secure confines of the monastery, the contemplation of sacred texts and images, and the cycles of ritual and worship, to engage themselves in society’s all-too-temporal concerns. Prior to 1800, such engagement included soldiering, trade, banking, protecting pilgrimage sites and religious endowments, and enlisting as mercenaries in the armies of regional states. But it also included living in villages amongst peasants, artisans, and laborers, and ministering to their daily religious needs. After 1800 and the colonial monopolization of armed force, involvement in society’s concerns meant, increasingly, attending to the vexed question of status and hierarchy, which seemed to have gained political urgency under British rule. Many monks in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, consequently, dedicated themselves to aggressive (and even, at times, egalitarian) social reform, which included the amelioration of the stigma of physical labor and the inculcation of a just moral order. And because monks confronted these issues in society, the issues eventually confronted them inside the confines of the monastery. The question of social status would consume the energies of numerous monks and peasants during much of the twentieth century; the discourses and ideologies brought to bear to deal with that question are the main concerns of this study.

A history of religious and social change runs up against numerous obstacles in India, not the least of which is the historiography produced by “communalism.” It has become by now a truism that colonial officials were quick to ascribe religious identity, particularly Hindu and Muslim “communal” identity, as the motivating force behind all precolonial conflict, in part as a way of justifying their own presence as representatives of a stabilizing, secular force.[20] What is less obvious is the extent to which the tentacles of colonial understanding have gripped Indian historical consciousness and the degree to which nationalist (and much postnationalist) historiography bears their circular scars. This wounded historiography contributes in no small way to the recent political impasse over a fully razed mosque and a partly raised temple in north India.[21] Unfortunately, coming to terms with this fact has often meant the historiographical withdrawal from any discussion of religion as a stimulus to historical change, either directly, as belief and ideology, or indirectly, as the discursive and institutional bases of social reform.

Applied to the day-to-day practicalities of imperial rule, the colonial fixation on an India—past and present—alllegedly rife with religious violence inspired colonial officials to distrust the very nature and content of Indian monasticism. This distrust was, in part, inspired by the at times vigorous (if unorganized) resistance offered by unruly bands of armed monks as the English East India Company subdued the huge province of Bengal. Nevertheless, the colonial willingness to see evil and corruption in the figure of the Indian monk was remarkable for its longevity and imaginative creativity. An early example of this can be seen in the writings of Colonel William Henry Sleeman (1788–1856), who is generally credited with the suppression of thagi (banditry, thought to have been ritually inspired) in the 1830s. Sleeman held that most Indian holy men were merely bandits, criminals, and rogues in disguise:

Sleeman also alleged that monks were guilty of spreading seditious rumors and recommended the compulsory registration of all such individuals according to a strict Vagrant Act.[23]Three-fourths of these religious mendicants, whether Hindoos or Muhammadans, rob and steal, and a very great portion of them murder their victims before they rob them.…There is hardly any species of crime that is not throughout India perpetrated by men in the disguise of these religious mendicants; and almost all such mendicants are really men in disguise; for Hindoos of any caste can become Bairagis and Gosains; and Muhammadans of any grade can become Fakirs.[22]

The colonial distrust of religion in the context of peasants (and soldiers) was also evident in the rumors that circulated throughout the empire over the outbreak of the 1857 rebellion. Two such rumors were of particular interest and were repeated by none other than Benjamin Disraeli in a speech to Parliament: namely, that the bloody events of that year were in part coordinated by religiously symbolic acts such as the mysterious passing of a chapati (thin wheat bread cooked over fire) from village to village and, in what was thought to strike an even deeper chord, the circulation of a lotus flower from sepoy to sepoy through entire regimental units.[24] Three decades later, in the 1890s, the often strident efforts of local sadhus to generate popular support in the countryside for a growing movement to prohibit the slaughter of cows in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar aroused great consternation among provincial officials—a consternation not unrelated to the widespread apprehension that the rebellion of 1857 had been sparked by the use of cow (and pig) fat in the cartridges of the new Enfield rifle.[25]

That sadhus generally were seen as a potential source of criminal mischief by officials of the Raj is evident in the publication in 1913 of a police handbook in Urdu that described the various religious orders and, in detailed line-drawings, examples of representative figures—down to the distinctive sandalwood-paste sect marks.[26] Sadhus would soon be considered a fount of outright sedition with the emergence of a newer form of resistance to colonial rule: mass nationalism. The colonial distrust of monks can be perceived not only in the early disdain for the Mahatma’s political style, but also in the official attitude toward monks in north India who gravitated toward Gandhi in the early 1920s. Such monks were derided in the police fact sheets as “political sadhus,” about whom almost no information was provided about monastic affiliations.[27] Indeed, if a common feature can be discerned in the tone of the police reports on “political sadhus,” it is the official attempt to dispute and discredit the religious credentials of the individuals under scrutiny. For example the police report depicted Swami Biswanand, who would become a prominent labor leader in the coal fields of south Bihar, as a person of “very bad moral character,” who was “absolutely inconsistent,” and whose “word or actions can never be relied on.” Another, Pursotam Das, was portrayed as “a man of low character, [who] frequents prostitutes’ houses,” and was said to have been “turned out of the Chatubhuj Asthan [monastery] by the Mahanth [head] for misconduct.” A third, Raghubar Saran Kuer, was cited for preaching “race hatred in a violent manner” and for abusing the police in filthy language; his allegedly weak religious loyalties could be seen in his willingness to shed his “sanyasi dress” and don the clothing of “a national volunteer,” i.e., Gandhian homespun cotton.

On first glance, then, the typical “political sadhu” of colonial India seems rather an unsavory fellow. However, the official record of the integrity and character of subjects under police scrutiny cannot be relied upon. It was only to be expected that police and intelligence officials would editorialize negatively about the morals, behavior, and sincerity of religious commitment of individuals opposed to colonial rule. Failure to do so would have risked the loss of important ideological ground to the agitators, and even the possibility of appearing politically unsound oneself. Whatever the “true” moral character of sadhus, their political actions were a function of religious and philosophical commitment and not a reflection of any alleged personal failings.[28] It is equally probable that their political behavior informed their religious outlook. As such, the “political sadhu” represented an important example of the ties that bound religious community, or sampraday, to society. Colonial administrators may not have appreciated the subtleties and importance of sampraday; they certainly feared, however, the power of sampraday loyalties to challenge even British imperial authority, and they strove therefore to dismiss the sampraday dimension of what they characterized as a political sadhu “problem.”

Despite colonial fears of the political sadhu and Gandhi’s own efforts to include sadhus in noncooperation as a symbolic challenge to the British, the colonial disdain for monasticism was to a large degree mirrored in nationalist circles. At the level of province and locality, the monastic orders would have been seen as a throwback to a premodern age, the sectarian complexities of which tended to undercut claims to Hindu political solidarity. Such claims were voiced with increasing stridency throughout the north after 1890, and in increasing proximity to Congress, by such organizations as the Arya Samaj, the Sanatana Dharma Sabha, and the Hindu Mahasabha.[29] Those sadhus willing to subordinate their sampraday loyalties to these new religio-political formations or, alternatively, to the philosophical (and nonviolent) dictates of Gandhi, would have remained within the ambit of nationalist politics, whether defined as secular or Hindu. Without question, many would have been driven away—though measuring such patterns of political involvement is difficult in the extreme. However, one revealing case is that of the peasant leader Swami Sahajanand Saraswati, who was drawn into nationalist politics in 1920–1921 by the force of Gandhi’s personality, but who would break publicly with Gandhi in the mid-1920s on the basis of his (Sahajanand’s) vision of the obligation of the monk to serve the needs of the oppressed peasant.[30] As I argue in chapter 4, Sahajanand Saraswati’s commitment to peasant welfare derived in large part from a conscious dedication to Vaishnava ideals of equality and social reform—notwithstanding the fact that he himself emerged out of a long tradition of Shaiva monasticism that competed vigorously with Vaishnava (and particularly Ramanandi) monasticism for the allegiances of peasant society.

In any event, Congress distaste and colonial disdain for sadhus would soon have historiographical consequences, as official documents and nationalist records emerged after Independence as the main sources for writing Indian political history, the only legitimate subjects of which were seen to be Congress, communalism, and colonialism. In that framework, the only significant figure accorded any kind of creative religious status was Gandhi himself; all other manifestations of socially engaged religion would be read backward from the dramatic events of 1946–1947 (and, later, 6 December 1992) as part and parcel of the communalism that would divide the subcontinent along lines Hindu and Muslim.[31] The work of a number of social historians of provincial politics would remedy to some degree the linear understanding of nationalist history by emphasizing the importance of local contingencies in the evolutionary dynamics of political institution-building.[32] However, insofar as those provincial histories were predicated upon understanding the local dynamics of nationalism, the eyes of these historians were still trained upon those individuals and institutions who articulated the new, totalizing religious sentiments.

In the past decade, a group of scholars referred to as the “subaltern collective” has criticized as “elitist” not only historical approaches that adopt colonial and nationalist agendas as thematic points of departure, but the heavy use of colonial and nationalist documentation (and the unconscious adoption of the mentalities therein). This criticism, though grounded in the conviction that the actions of peasants and workers—“subalterns”—should be understood as part of a failed history of national fulfillment, can also be leveled from the perspective of religion.[33] For members of the subaltern collective, the poverty of this “elitist” historiography is

demonstrated beyond doubt by its failure to understand and assess the mass articulation of this nationalism except, negatively, as a law and order problem, and positively, if at all, either as a response to the charisma of certain elite leaders or in the currently more fashionable terms of vertical mobilization by the manipulation of factions. The involvement of the Indian people in vast numbers . . . in nationalist activities and ideas is thus represented as a diversion from a supposedly ‘real’ political process, that is, the grinding away of the wheels of the state apparatus and of elite institutions geared to it, or it is simply credited, as an act of ideological appropriation, to the influence and initiative of the elite themselves.

This powerful critique has had the potential to galvanize much historical writing by bringing historians closer to the voices and actions of ordinary people as they grappled with the changes overtaking their lives. An excellent case in point is the subaltern consideration of Baba Ramchandra, a man who would have been disparaged as a “political sadhu” by the government but who was in fact the central instigator of peasant dissent in Awadh between 1919 and 1922. In revisiting this important moment of agrarian radicalism, the historian Gyanendra Pandey contrasts the peasant world of Awadh to the conception of the peasant held by Gandhian nationalists and by the colonial state, and demonstrates thereby the conflicting aims of Indian nationalism and peasant rebellion. Baba Ramchandra is introduced as “a Maharashtrian of uncertain antecedents who had been an indentured laborer in Fiji and then a sadhu (religious mendicant) propagating the Hindu scriptures in Jaunpur, Sultanpur and Pratapgarh, before he turned to the task of organizing Kisan Sabhas [peasant associations].” As a peasant leader, he evoked the moral world of the god-king Ramchandra of epic Ayodhya to combat expropriative landlord tyranny. That moral world was described in Tulsidas’ Ramcharitmanas, “a favourite religious epic of the Hindus in northern India and especially beloved of people in this region”; its immediacy in the agrarian environment was reflected in the increased currency of such religiously charged phrases as “Sita Ram,” “Jai Ram,” and “Jai Shankar” as both egalitarian forms of address and as rallying calls for peasants gearing up for political action.[34]

Hidden in the shadows of the subaltern consideration of Baba Ramchandra are the social and religious institutions that underpinned the agrarian radicalism of Awadh. Such institutions provided an autonomous peasant and monastic culture organized to work for progressive change, whether in the context of economic crisis, political mobilization, social reform, or spiritual awakening. It was because of their ties to peasant society through important religious communities that Baba Ramchandra and other sadhus (Sahajanand Saraswati for example) could engage in peasant politics so effectively. In the nineteenth and twentieth-century Gangetic north, many sadhus were committed to a powerful critique of hierarchy that came to constitute a major principle behind social and ideological change. The most important, but by no means the only, proponent of such change in Gangetic north India was the Ramanandi sampraday. Ramanandi social commentary gained institutional momentum over the centuries, but was extremely influential by the early 1800s, as peasant society gravitated toward its progressive and assimilative rhetoric. Baba Ramchandra was very much part of that Ramanandi, Vaishnava ethos, a fact that contributed substantially to his immediate and positive reception by landless and land poor peasants in the countryside.[35]

The links between monks and peasants before the twentieth century were best represented by the individuals and establishments that made up the Ramanandi sampraday. By the turn of the twentieth century, new ideological movements began to emerge from within peasant society itself, spearheaded by populist scholars who asserted genealogical descent in the royal kshatriya (warrior) lineages of Ram and Krishna, Vishnu’s avatars (earthly forms). Baba Ramchandra’s recollections of the peasant dissent in Awadh, not to mention his own recruitment into the peasant movement, place great emphasis on the organizational framework of peasant-kshatriya identity campaigns that were already in place.[36] It should be emphasized that without such a framework peasant activism would have been far less successful and may even have failed to attract the attention of Congress leaders and the colonial state, not to mention later generations of historians.

More recently, the work of Sandria Freitag on community and communalism in the Gangetic north has also focused on the trajectories of popular action in the context of the emergent Indian nation but has distinguished itself from subaltern scholarship by closer attention to the autonomy of cultural and religious change, particularly as expressed in collective action and the symbolic language of crowd violence. For Freitag, religion provided the institutional base for “public arena” activities, such as festivals, in which increasingly wide community identities were expressed with greater political urgency as the colonial era drew to a close.[37] Her stress on popular action (and riots in particular) rather than ideas has the effect of deemphasizing religious ideology as a causal factor in a history that seeks to explain something with massive ideological ramifications, namely, Hindu versus Muslim communalism. This effect is both necessary and intended: Freitag notes at the outset that while we have access to the symbolic language expressed through collective action over time, we cannot know the thoughts of individual rioters as they go about their business.[38] Hence it would be fruitless to speculate on the ideologies that motivated rioters or whether something so finite and discernible as ideology was at work. More importantly, the focus on action in the frame of the public arena provides sufficient evidence to argue that communalism (and, ultimately, Partition) was an unintended consequence of shortsighted colonial strategies combined with nationalist political culture, rather than the political fruition of “age-old” animosities expressed in “insensate violence,” as the colonial mythology would have it.

Beneath and within the actions of crowds accommodating themselves to the logistical needs of the colonially malformed and increasingly communalized public arena, however, were significant religious ideologies that were neither Hindu nor Muslim in the political sense. Acknowledging this fact affords greater historical and cultural depth to the history examined by Freitag. For example, after 1900 the colonial state became increasingly concerned with the Ram Lila festival, which reenacted annually the life of the god-king Ramchandra in towns and villages throughout the Gangetic north. Official consternation derived from politically motivated innovations in the festival, such as the inclusion of famous rebels from 1857 and well-known extremists (e.g., the Rani of Jhansi on horseback with a British soldier transfixed on her spear, and Lala Lajpat Rai, the fiery Arya Samajist Congressman from the Punjab) in the festival tableaux and processions.[39] As the annual occasion for the celebration of the life of Ramchandra, the Ram Lila was central in the ritual calendar of all Ramanandis. In Ramnagar (across the Ganga from Banaras), the feasting of hundreds of Ramanandi sadhus during the festival afforded substantial political legitimacy to the Maharaja of Banaras, who sponsored the annual performance at considerable expense. The Ramnagar Ram Lila would grow into a thirty-one-day affair and would be performed in an elaborate—and permanent—reproduction of Ayodhya housed within the palace grounds.[40] But whether in Ramnagar or in villages and towns throughout the north, the Ram Lila took on an added importance for peasants claiming (after 1900) a lineal descent from the kshatriya house of Ramchandra, because it represented an annual opportunity to imbibe the grandeur and glory of their most famous progenitor. Hence, to fully appreciate the historical significance of the Ram Lila, it must be understood in the context of Ramanandi monasticism and peasant-kshatriya identity. Together they point to a Vaishnava religiosity on the rise in precolonial and colonial India beneath the rubric of Hinduism that would seek to overtake such religiosity in the twentieth century.[41] Like Hinduism, Vaishnavism was grounded in a long process of institutionalization in festival, pilgrimage, temple construction, monasticism, and mythology. What is more, this institutionalization depended on the creative tensions between political power and religious authority in the precolonial period, prior to the nineteenth-century withdrawal of the state from the popular spectacle that became such a crucial public arena.

Given the degree to which religion obtruded into the political process in colonial India, studies of political action predicated on religious institutions can and should be complemented by inquiries into the political meanings of religion. The injection of the cultural into social history has moved us carefully in this direction, but neither the sporadic irruptions of subaltern rebellion nor the long-term patterns of crowd violence, however eloquent, can speak adequately to the full import of religious ideology in social history. Admittedly, this poses a problem for historians of India, because any study of religion as a motive force in political and social change can be misconstrued as an argument for the fundamentally religious basis of Indian politics. It also poses a problem for many social historians of peasant society, who tread softly when it comes to assessing religion in terms of meaning, since religious consciousness tends to cut across the class lines that make social-historical analysis so meaningful. Notwithstanding these risks, this foray into the religious world of the peasant is especially called for, if for no other reason, because the peasant world was, in large part, religious. Were we to obscure that fact in our historical representation of peasant society, we would be depriving peasants—about whom so much has been written as agents of their own history—of the historical voice they know best. And we would be depriving ourselves, as historians, of important insights not only regarding peasant history but into the ways ordinary people came to terms with the decline of colonial rule and the rise of an Indian nation.

| • | • | • |

Britain, India, and British India

British India was not simply a place but an amalgam of ideas, politics, and people both British and Indian. The extended exchange of meaning that occurred between Britain and India, the most visible result of which may well be the idea of caste, figures prominently in the emergence of peasant-kshatriya identity and also (though perhaps in a more subtle manner) in the history of Ramanandi monasticism. Hence it is appropriate to describe at the outset the political-cultural dimensions of the colonial world and the ways in which that world touched the lives of peasants and monks in Gangetic India.

The cultural and intellectual exchange between Indians and Britons in colonial India was predicated on an imbalance of power; notwithstanding the ugly face of imperialism (and perhaps because of it), this exchange shaped the very dimensions of colonial culture and turned (to borrow the phraseology of the psychologist Ashis Nandy) India and Britain into intimate enemies. The British empire in India depended upon the effective organization, maintenance, and exercise of force, material as well as ideological. For Nandy, however, more important than any military ordnance was the idea of imperial power, embodied in colonial India by the notion of martial valor. The central implication of that important idea in the psychology of imperial rule was the rise and eventual dominance of a muscular, hyper-masculine ethos in imperial India. Hence, “many nineteenth-century Indian movements of social, religious and political reform . . . tried to make Kshatriyahood the ‘true’ interface between the rulers and the ruled as a new, nearly exclusive indicator of authentic Indianness.”[42] It has been suggested in response to Nandy that the search for a martial Indianness only occurred in a narrow “zone of contact,” a zone restricted to the urban world of bureaucracy, scholarship, and nationalism and peopled with the “self-conscious Indians” who were “the elite, the articulate, the Westernized.” Accordingly, we should seek to know more about the other Indian “‘out there,’ in the villages far from the Western experience, who is not consciously embattled by the West, not torn about his Indianness, who carries on being his Indian ‘self’ without a sense of the historical problematic in which he is unwittingly situated.”[43]

The peasants of British India were the villagers who lived “far from the Western experience.” However, the history of kshatriya reform, which spoke directly to the question of status in a distinctly colonial society, suggests that they were in fact not so greatly removed from the “zone of contact.” Torn less about their “Indianness” than their British-Indianness, they were at least as concerned with questions of self and identity as their “westernized, intellectual” compatriots, particularly those in the elite nationalist movement. The aggressive articulation of kshatriya identity in the early twentieth century is evidence of the extent of their involvement in the colonial culture; the desire to appropriate a kshatriya ideal extended deep into peasant society, to productive cultivators on the margin of land-control and status in the Gangetic countryside. Further, what people “out there” wrote, discussed, and believed was based on a sense of the past that relied on myth, legend, and lineage, not to mention British examinations and recapitulations of that myth, legend, and lineage. However, the articulation of peasant-kshatriya identity differed in significant ways from the kshatriyahood of the colonial elite in that the latter usually combined martial status with landed power, imperial certification, and brahmanical patronage. Peasant kshatriyahood, by contrast, lacked all these assets, but drew on Vaishnava identities and discourses nurtured in part by institutional connections to Vaishnava—particularly Ramanandi—monasticism. And, though that monasticism existed in religious centers located far (ideologically if not geographically) from the western experience, it too spilled over on occasion into the “zone of contact.”

It has been argued that the popular concern with identity and status was part of, and perhaps a response to, processes of ideological change centered on the notion of caste in British-Indian society—particularly in proximity to the census office.[44] Certainly the thoughts, words, and deeds of peasants and monks in the colonial era confirm that caste was a subject of great interest to all, in large part because the ideology of inequality and status (and, by implication, equality and identity) implicit to caste enabled individuals, communities, and the state to facilitate, moderate, or obliterate social change. And certainly the caste we have come to know in the late twentieth century is in part (some would say in large part) the product of a colonial discourse: British imperial anthropology manifest by the late nineteenth century in a pervasive British-Indian census bureaucracy, which inadvertently reified brahmanical hierarchy—or an ideology of inequality articulated by brahmans who resided atop that hierarchy—as part of a process of colonization writ cultural.[45]

But while the empire can be held accountable for many evils, one suspects that the full burden of caste injustices cannot be laid squarely on its shoulders. Status and social rank—and the peasant, monastic, and colonial fixation on status and social rank—should be understood as part of a much older, though perhaps more socially restricted, Indic discourse of varna. Scholars have disagreed widely on the degree to which varna represents an integrated, all-encompassing model of and for Indian social relations;[46] few, however, contest the precolonial existence of the discrete religious, political, and economic roles of priest (brahman), warrior (kshatriya), merchant (vaishya), and servant (shudra) that make up varna. That varna was conceived by brahmans in the distant past as an implicitly hierarchical division of labor is confirmed by the unimpeachable antiquity of the myth of the primordial man, from whose head and mouth sprang brahmans, torso and arms kshatriyas, loins and thighs vaishyas, and legs and feet shudras.[47] These ideas did not require a European colonial state to ensure their ideological longevity; they did require, however, certain enforced inequalities (including gender inequalities) in post-Vedic, precolonial Indian society—a detailed consideration of which is, fortunately, beyond the scope of this study.

While we can presume that, historically, most brahmans and perhaps many kshatriyas and vaishyas subscribed to the hierarchy implicit in varna, we cannot know the extent to which that subscription was shared by shudras. The historiography of ancient and medieval India suggests that shudras did not necessarily care for the servile status ascribed to them.[48] The principle of social hierarchy, and the fundamental human inequalities that it implied, would have been even more repellent to a substantial portion of the population relegated to a social realm beyond and therefore below the four varna and existing by definition on the periphery of society. Members of this group of perennial outsiders, bound in economic, political, and social servitude to varna society in intricate and myriad ways, have been known generally by a variety of names. They have been derided as dasyu (barbarian), dasa (slave), paraiyan (pariah), and untouchable; they have been patronized as harijan (as Gandhi’s children of god) and scheduled (as names on a government list); and they have asserted themselves as untouchable, achhut (untouched) and, more recently, dalit (oppressed).[49] For historians seeking to understand the history of this underclass prior to the twentieth century, however, its voices are difficult to discern.

Untouchable, shudra, vaishya, kshatriya, and brahman are large, unwieldy categories. Rendering them socially and economically practicable are a plethora of occupational groupings, known generally as jati, that developed over time in Indian society and inclusion in which was thought to be predicated on birth. The thousands of extant jati identities are theoretically locatable within the fourfold varna hierarchy or, without, as untouchables.[50] To the extent the Indic social order was value-laden and led to axioms of physical, moral, and intellectual superiority and inferiority, varna (and the untouchability it implies) represents an interesting analogue to the western notion of race. However, varna and race have differed not only according to strict definitions, but insofar as they evolved in distinctly different geographic, material, and human environments. As is well known, those environments suddenly overlapped with the arrival of the Portuguese near the turn of the sixteenth century, the result of which was the hermeneutic of caste. Caste, and the racial hierarchy that it came to evoke for many Indians and Britons alike, is an important hybrid (and historically locatable) idea that permeates much of the colonial past and the people who lived it.

The colonial understanding of India, increasingly centered on caste,[51] relied on a corps of elite officials who sought to understand and compartmentalize the complexity of religious, cultural, and social life and who presented their amassed data in gazetteers, census reports, surveys, and other encyclopedic compendia. Typical north Indian examples of such men are Francis Buchanan (later known as Francis Hamilton, 1762–1829), James Tod (1782–1835), Henry Miers Elliot (1808–1853), W. W. Hunter (1840–1900), William Crooke (1848–1923), H. H. Risley (1851–1911), George Grierson (1851–1941), and L. S. S. O’Malley (1874–1941). They and others like them worked either for the English East India Company or for the Government of British India. Their role was to study, interpret, and report on Indian society; their research was based on translation, linguistic analysis, philological speculation, statistical surveys, textual study, ethnography, anthropometry, and observation; and their understanding was heavily colored by their cultural predispositions, administrative functions, and political roles. The volumes they produced immediately entered the public domain and, as politically vital information, became authoritative ethnographic, cultural, and historical texts for Europeans and Indians alike. In short, Indian meaning—of obvious importance to the successful functioning of government—was collected, analyzed, and reproduced in standardized form by the ruling power. This bringing of Indian meaning to political authority was not only necessary for administration, but also served to politically revalidate that body of knowledge. It is not entirely surprising, therefore, that peasant ideologues looked to this official literature in the twentieth century to buttress their kshatriya identities.

Insofar as the official literature often drew on elite Indian sources, especially with respect to caste, this process should also be seen as an official certification of a brahmanical discourse of hierarchy. Great caution must be utilized, therefore, when drawing upon this literature in the context of kshatriya reform, to ascertain whether hierarchy was in fact being popularized or whether it was being manipulated and thereby subverted. Another reason to exercise caution with the official literature—inspired in part by the publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism—is the fact that the information therein is colored by the colonial predispositions of its British authors.[52] It is true that all interpretation falls victim at some point to cultural and psychological subjectivism; as Nandy points out in his effort to comprehend the salient psycho-cultural dimensions of colonialism, “The West has not merely produced modern colonialism, it informs most interpretations of colonialism. It colours even this interpretation of interpretation.”[53] Like Nandy, we should endeavor to focus upon our own interpretive dilemma and put it to good analytical use, thus making our work all the more meaningful.

By identifying the cultural—and, with Nandy, the psychological—subjectivity of British interpretation in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, we can speculate about the nature of British-Indian society during the colonial period. A bulwark of colonial power was the colonial elite’s conception of Indian society, especially the idea of caste. Caste was the ideological linchpin of colonial authority, a language of race spoken by the powerful and understood by the powerless, and therefore central to the colonial Indian world. But, as the historian Nicholas Dirks has cautioned, “The assumption that the colonial state could manipulate and invent Indian tradition at will, creating a new form of caste and reconstituting the social, and that a study of its own writings and discourse is sufficient to argue such a case, is clearly inadequate and largely wrong.”[54] All the arguments of the cultural hegemony of the colonial state notwithstanding, what is presented in British understanding reflected a form of Indian social, cultural, and religious reality. Historians can and should learn not only from the reflected reality, but from the mode of reflection itself. Going one step further, it can be argued that one cannot be utilized to the exclusion of the other. As a reflection of reality, caste and the body of orientalist literature upon which it relied represents one side of an emergent British-Indian dialogue, a dialogue that developed dialectically into a cultural system all its own: partly British, partly Indian, wholly British-Indian. The other side of that dialogue—grounded in a popular discourse that was all-too-infrequently perceived by colonial officials, not to mention postcolonial scholars who rely overly on colonial commentary—is the understanding and reshaping of social relations by peasants and monks in colonial north India.

The way these peasants and monks came to terms with varna, jati, race, and caste thus forms the central problem of this study. Peasants and monks were particularly well poised to examine these concepts in the context of political action and religious identity in the colonial period. The former were regarded as of low status (i.e., shudra), ostensibly because of their engagement in agricultural labor. Yet their position of relative social inferiority was offset by their significant demographic strength, their centrally productive role in society, and the opportunities for economic advancement that confronted them in the nineteenth century. Buoyed by these material strengths, peasants in Gangetic India began to reject the shudra definitions ascribed to them by the social elite. Likewise, monks did not stand aloof from the worldly concerns of status and hierarchy but remained intensely devoted to a commentary and, more often than not, a critique of that world. The many ways peasants and monks conceived of social relations constituted not only important and overlapping arenas of cultural change during the colonial period, but informed the conception of race and caste after independence from British rule in 1947.

What emerges then is that “Hindu” ideas have impinged in important ways on social and political change in Indian history. This should not appear surprising, inasmuch as the term Hindu has long communicated social and political meaning. Persians, Greeks, and Arabs first used variations of the term Hindush as a geographic designator to describe the territory to the east of the Indus (ancient Shindu) River; “Hindu” later came to be used by Turkish, Persian, and finally European (and especially British) observers as a religious signifier describing someone who followed a system of beliefs (today collectively termed “Hinduism”) distinct from the then more familiar Islam.[55] In fact, as the etymological development of this term would indicate, Indian religion may have been too complex and discrepant to be described adequately under the single rubric, as a Hindu-ism. A systematic Hinduism did of course emerge in recent centuries, influenced in part by European attempts to understand Indian religion according to European paradigms, in part by a nationalist movement that sought to draw on noncontradictory religious meanings, and in part by religious reformers who sought to reconcile regional religious contradictions so as to participate in the emerging Indian political discourse of nation and race. Underneath the rubric of that emergent, “modern” Hinduism existed a divisible multiplicity of overlapping religious systems. In the Gangetic north this included, by the eighteenth century, expanding monastic institutions of Vaishnava belief centered on bhakti, or love for God. Vaishnava bhakti, or the conception of Vishnu and his avatars as deserving of complete devotion, is the religious ground upon which much of the ideological change described in this study takes place. The following pages are an attempt to reinvest those terms with social and political meaning and in the process instill in social and political history a sense of cultural change.

Notes

1. For definitions of peasant society, see Daniel Thorner, “Peasantry,” in David Sills, ed., International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (New York: Macmillan, 1968), 11:508; Teodor Shanin, “Peasantry: Delineation of a Sociological Concept and a Field of Study,” European Journal of Sociology 12 (1971): 289–300; and Sidney Mintz, “A Note on the Definition of Peasants,” Journal of Peasant Studies 1, no. 1 (1973): 91–106. Also useful are the historiographical discussion in David Ludden, Peasant History in South India (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), 3–14, and the contradictions of community and class inherent in peasant society noted by Victor V. Magagna, Communities of Grain: Rural Rebellion in Comparative Perspective (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991), 2–21.

2. Richard B. Barnett, “Images of India from Alexander to Attenborough,” Jefferson Society lecture, University of Virginia, 16 September 1983.

3. For an introduction to the complexity of Hindu monasticism, see G. S. Ghurye, Indian Sadhus (1953; 2d ed., Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1964); and Parshuram Chaturvedi, Uttari Bharat ki Sant-Parampara [The North Indian Sant Tradition], 3d ed. (Allahabad: Leader Press, 1972).

4. All three monastic lifestyles—itineracy, spiritual study, and soldiering—can be contained within one order; see Peter van der Veer, Gods on Earth: The Management of Religious Experience and Identity in a North Indian Pilgrimage Centre (London: Althone, 1988).

5. An important study in this field is Kenneth G. Zysk, Asceticism and Healing in Ancient India: Medicine in the Buddhist Monastery (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991).

6. Hence, implicit to this study are questions not unlike those that concerned A. Appadurai in Worship and Conflict under Colonial Rule: A South Indian Case (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 6–7: What are the relationships between the religious, the political, the economic, and the social in colonial India? What underpins hierarchy in the social order? And how do we define and measure change in the caste system?

7. See, for example, János M. Bak and Gerhard Beneke, eds., Religion and Rural Revolt (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984).

8. The role of Saya San (1930s) in lower Burma and Swami Sahajanand Saraswati (1920s to 1940s) in north India are but two examples; on the former, see James Scott, The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976); on the latter, see Walter Hauser, The Politics of Peasant Activism in Twentieth-Century India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, forthcoming), and Hauser, ed., Sahajanand on Agricultural Labor and the Rural Poor (New Delhi: Manohar, 1994).

9. Peter Brown, “The Rise and Function of the Holy Man in Late Antiquity,” in Society and the Holy in Late Antiquity (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982), 105–6.

10. Hence this history should be understood as an important part of the process of ideological change described by Peter van der Veer in Religious Nationalism: Hindus and Muslims in India (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994).

11. The material for such an inquiry must be based largely on vernacular sources that reflect the conscious ideologies of peasants and monks and reveal the unconscious discourses in which they participate. In saying this, however, I do not wish to suggest that vernacular sources are somehow more “authentic” than official or nonofficial (i.e., nationalist) English-language sources; both must be approached with the utmost caution so as to “distinguish what they describe from what they attempt to explain” (Sandria Freitag, Collective Action and Community: Public Arenas and the Emergence of Communalism in North India [Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989], 16). In English-language documents this entails peeling away the layers of colonial or nationalist apprehensions; vernacular sources may also contain some of these apprehensions, but with a strong overlay of religious and social polemic.

12. Ronald Inden, Imagining India (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1990), particularly chapters 3 and 4.

13. See Lewis Wurgaft, The Imperial Imagination: Magic and Myth in Kipling’s India (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1983), for an engaging venture into the psychohistorical and literary dimensions of this idealization.

14. Shahid Amin, “Gandhi as Mahatma: Gorakhpur District, Eastern UP, 1921–22,” in Ranajit Guha, ed., Subaltern Studies: Writings on South Asian History and Society, vol. 3 (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1984), 1–61.

15. Government of Bihar and Orissa (GOBO), Political Department, Special Section, file no. 80 of 1921, “Report of Sadhus taking part in non-cooperation,” part 2, 3, Bihar State Archives, Patna. The observer was Krishna Ram Bhatt, an employee of the Tata Iron and Steel Company at Jamshedpur in Bihar; his observations are taken from paragraph 73 of the Bihar and Orissa Police Abstract of Intelligence in the above-mentioned file. See the following chapter for a discussion of soldier monasticism.

16. GOBO, Political Department, Special Section, file no. 80 of 1921, part 2, 3. One crore, or kror, is equal to ten million; hence Bhatt is referring to the entire population of India.

17. GOBO, Index to the Proceedings of the Political Department, Special Section, in the Bihar State Archives, indicates numerous reports compiled on the subject of “political sadhus,” especially between the years 1920–35, when Gandhi dictated the terms of Indian politics. As I note below, this represented a renewed interest in the politics of monasticism on the part of colonial officials.

18. Anandamatha, trans. Basanta Koomar Roy (1941; reprint, New Delhi: Orient Paperbacks, 1992); Jawaharlal Nehru, The Discovery of India (New York: John Day, 1946), 44. Anandamatha was originally published in 1882 in Bangadarshan, Bankim’s literary monthly, and subsequently translated into English as The Abbey of Bliss by Nares Chandra Sen-Gupta (Calcutta: M. Neogi, 1906). On the circumstances of Bankim’s authorship, see Tapan Raychaudhuri, Europe Reconsidered: Perceptions of the West in Nineteenth-Century Bengal (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1988), 117 and passim.

19. See the reflections of van der Veer, Religious Nationalism, on the constituent elements of nation implicit to the Indian context.

20. See Gyanendra Pandey, The Construction of Communalism in Colonial North India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1990), esp. 23–65, “The Colonial Construction of the Indian Past.”

21. Romila Thapar, “Interpretations of Ancient Indian History,” History and Theory 7, no. 3 (1968): 318–35; and “Religion, Communalism, and the Interpretation of Indian History,” public lecture, Wesleyan University, 18 November 1992. See also K. N. Panikkar, “A Historical Overview,” in S. Gopal, ed., Anatomy of a Confrontation: The Babari Masjid-Ramjanmabhumi Issue (New Delhi: Penguin, 1990), 22–37.

22. Sleeman, A Report on the System of Megpunnaism or, The Murder of Indigent Parents for their Young Children (who are sold as Slaves) as it prevails in the Delhi Territories, and the Native States of Rajpootana, Ulwar, and Bhurtpore (Calcutta: Serampore, 1839), 11.

23. This recommendation was not acted upon by the government. Sleeman’s opinions were part of the ever-widening scope of colonial police power in the early nineteenth century, and the bandits and thugs that he sought to supress were holdovers of institutionalized violence from an era when the reach of the state was not nearly so total. See Stewart Gordon, “Scarf and Sword: Thugs, Marauders, and State-Formation in Eighteenth-Century Malwa,” Indian Economic and Social History Review 6, no. 4 (1969): 403–29.

24. See Disraeli’s speech to Parliament, 27 July 1857, partially reproduced in Ainslee T. Embree, ed., 1857 in India: Mutiny or War of Independence? (Boston: D. C. Heath, 1963), 11–12.

25. Freitag, Collective Action and Community, 161–62. Note in particular the activities of Sriman Swami and Khaki Baba (also known as Khaki Das).

26. Saiyyid Muhammad Tassaduq Hussain, Kitab-i Sadhu [The Book of Sadhus] (Sadhaura, Umballa District: n.p., 1913). The author is described as “Head Constable, Saharanpur Police Lines”; the book is dedicated to P. B. Bramley, then Deputy Inspector General of Police, and on p. 5 it is noted that the work was sanctioned by Government Order no. 3232 of 1913.

27. These individuals were described in history sheets sent from R. S. F. Macrae, of the Bihar police, to E. L. L. Howard, chief secretary to the Government of Bihar and Orissa, 3 November 1921, and included as appendices in GOBO, Political Department, Special Section, file no. 80 of 1921, part 2, 8–20.

28. See Ranajit Guha, Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983), 106–8, on the postcolonial historiography of rebellion and the unfortunate tendency of the historian’s voice “to merge with that of the local sub-divisional officer as he speaks of the ‘bad characters’ and ‘the criminal sections’” (107).

29. See C. A. Bayly, The Local Roots of Indian Politics: Allahabad, 1880–1920 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975); and John R. McLane, Indian Nationalism and the Early Congress (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977), part 4.

30. Walter Hauser, “Swami Sahajanand and the Politics of Social Reform,” presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Asian Studies, Washington, D.C., 4 April 1992. Hauser quotes Swami Sahajanand Saraswati’s autobiography, Mera Jivan Sangharsh [My Life Struggle] (Bihta, Patna: Shri Sitaram Ashram, 1952), 185 and (on Saraswati’s relations with Gandhi more generally) 212–13. Hauser’s essay is forthcoming in the Indian Historical Review 18, no. 2 (January 1992), which is now over two years behind schedule; I am grateful to the author for allowing me to cite the original.

31. On this historiographic problem, see Freitag, Collective Action and Community, 8–12.

32. Bayly, Local Roots of Indian Politics, exemplifies this approach.

33. Ranajit Guha, “On Some Aspects of the Historiography of Colonial India,” in Guha, ed., Subaltern Studies: Writings on South Asian History and Society, vol. 1 (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1982), 1–8; for the quote below, 3.

34. Gyanendra Pandey, “Peasant Revolt and Indian Nationalism: The Peasant Movement in Awadh, 1919–22,” in Guha, ed., Subaltern Studies, 1:147–48, 168–71. The subaltern approach, grounded in a Marxist-Gramscian historical framework, can obscure the sampraday that is implicit to most sadhus and therefore overlook the subtle yet important religious and political meanings in the history of Indian political consciousness. Here, for example, Pandey tantalizes the reader with fragments of information regarding the religious context out of which Baba Ramchandra emerged, and then dismisses that context as “the hold of religious symbols on the mind of the peasant” (171) before returning to the more urgent questions of agrarian exploitation, peasant violence, Congress elitism, and colonial manipulation. A similar approach can be discerned in Guha, Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency, 18, who sees religion as an ideological force that sustains the negative self-image of the peasant “by extolling the virtues of loyalty and devotion, so that he could be induced to look upon his subservience not only as tolerable but almost covetable.” See also Guha’s discussion of the springtime festival of Holi, 33–36 and passim.

35. This has been elaborated by Philip Lutgendorf, The Life of a Text: Performing the Ramcaritmanas of Tulsidas (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1991), 374–78. In a rich discussion of peasant mobilization in Awadh that in many ways presaged Pandey’s work, Majid Siddiqi, Agrarian Unrest in Northern India (New Delhi: Vikas, 1978), 113, observed that Baba Ramchandra’s popular appeal was derived in large part from the fact that he carried a copy of the Tulsidas Ramayana on his back and was able to recite from it with considerable force; this point is pursued in greater detail in Kapil Kumar, “The Ramacharitamanas as a Radical Text: Baba Ram Chandra in Oudh, 1920–1950,” in Sudhir Chandra, ed., Social Transformation and Creative Imagination (New Delhi: Allied, 1984).

36. Noted in Pandey, “Peasant Revolt and Indian Nationalism,” 167–68. See also Siddiqi, Agrarian Unrest, 110, 117.

37. Collective Action and Community. Freitag argues that communalism is the result of a combination of historical developments, beginning in the nineteenth century with a gradual state withdrawal from involvement in important urban public occasions, such as religious festivals, in favor of a new brand of imperial assemblage wherein large landholders—deemed the “natural” leaders of British India—ritually subordinated themselves to the British monarch. This colonial withdrawal from the popular stage afforded local urban notables, themselves prohibited from participation in imperial politics, a public arena in which status could be expressed and confirmed. With the rise of nationalist sentiment in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century India, the same local notables would gradually reshape the public arena to accommodate an Indian version of nation. As the public arena became nationalized, the national need for an “other” against which to measure itself was projected onto the public arena as communal antagonism. Communalism represented, then, a necessary evil that colonial, nationalist India had to internalize as part of the process of becoming an independent nation-state.

38. Ibid., 16. A danger of the focus on crowd behavior as text (an approach that the subaltern collective shares) is that people are defined not by what they believe, think, say, and write, nor by the alliegances they claim, but solely by what they do. In order to exist for the historian they must act collectively against an other; when they are quiescent, or even when they work toward a goal that engages no immediate and vociferous opposition, they escape notice. When they riot, they accommodate themselves to the logistical needs of a public arena that make no room for complex identities. See Freitag, Collective Action and Community, 239–41; and Sumit Sarkar, “The Conditions and Nature of Subaltern Militancy: Bengal from Swadeshi to Non-Co-operation, c. 1905–22,” Subaltern Studies, 3:273–74.

39. Freitag, Collective Action and Community, 199–209.

40. Ibid., 28–31; and Richard Schechner and Linda Hess, “The Ramlila of Ramnagar,” Drama Review 21, no. 3 (1977).

41. See also in this context Lutgendorf, The Life of a Text, chapters 5 and 6.

42. Ashis Nandy, The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self under Colonialism (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983), 7. The ramifications of the colonial kshatriya ideal included the ideological evolution of an Indian Homo militaris, bred to serve in the ranks of the British Indian army. See Richard Fox, Lions of the Punjab: Culture in the Making (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1985), esp. 27–51, 140–59. The “search for martial Indianness” also bred anti-imperial ideologies, such as the “immensely courageous but ineffective terrorism of Bengal, Maharashtra and Panjab led by semi-Westernized, middle-class, urban youth” (Nandy, The Intimate Enemy, 7).

43. A. Appadurai, “Is Homo Hierarchicus?” American Ethnologist 13, no. 4 (November 1986): 748–49. See also Nandy, Intimate Enemy, 31–32.

44. Imtiaz Ahmad, “Caste Mobility Movements in North India,” Indian Economic and Social History Review 7, no. 2 (1971): 164–91; and Lucy Carroll, “Colonial Perceptions of Indian Society and the Emergence of Caste Associations,” Journal of Asian Studies 37, no. 2 (1978): 233–50. These studies are not concerned with monastic society, as such. See chapter 4 for a lengthier discussion of the arguments forwarded in these essays.

45. See Nicholas B. Dirks, “Castes of Mind,” Representations 37 (Winter 1992): 56–78; and Bernard Cohn, “The Census, Social Structure and Objectification in South Asia,” in An Anthropologist among the Historians and Other Essays (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1990), 224–54. Both Dirks and Cohn note the distinction between a colonial discourse of caste and Indian conceptions of social relations. For useful clues to the social and ethnohistorical ramifications of both, see Christopher A. Bayly, “Peasant and Brahmin: Consolidating Traditional Society,” chapter 5 of Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), esp. 155–68; and Dirk H. A. Kolff, Naukar, Rajput and Sepoy: The Ethnohistory of the Military Labour Market in Hindustan, 1450–1850 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

46. For an introduction to these disagreements, see Louis Dumont, Homo Hierarchicus? The Caste System and Its Implications, trans. Mark Sainsbury, Louis Dumont, and Basia Gulati (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980); and Appadurai, “Is Homo Hierarchicus?”

47. See The Laws of Manu, introduction and notes by Wendy Doniger, trans. Doniger and Brian K. Smith (New York: Penguin, 1991), 6 (Manusmriti I.31). According to Doniger, this myth appears in the much earlier Rg Veda10.90. As for structural interpretations of this hierarchy, see Dumont, Homo Hierarchicus 67–68, and on caste and varna, 72–75; and Edmund Leach, “Caste, Class and Slavery: The Taxonomic Problem,” in Anthony de Reuck and Julie Knight, eds., Caste and Race: Comparative Approaches (Boston: Little, Brown, 1967), 10–11.

48. This is evident in the fact that shudras have aspired successfully to kingship and have manipulated genealogies to provide themselves with “acceptable” kshatriya antecedents. See Romila Thapar, “Genealogy as a Source of Social History,” Indian Historical Review 2, no. 2 (January 1976): 259–81; and “Society and Historical Consciousness: The Itihasa-Purana Tradition,” in S. Bhattacharya and R. Thapar, eds., Situating Indian History for Sarvepalli Gopal (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1986), 353–83. The fabrication of kshatriya genealogies is not a universal impulse throughout the subcontinent, however; of particular note are the Nayaka kings of Tamilnadu who were said to have glorified their shudra origins. See V. Narayana Rao, D. Shulman, and S. Subrahmanyam, Symbols of Substance: Court and State in Nayaka Period Tamilnadu (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1992). I am grateful to Dr. Sandria Freitag for bringing this reference to my attention.