PART ONE—

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

Part One consists of five chapters that focus on historical events, from earliest times to most recent, that have determined the current status of California's salmonid resources and suggest likely future developments. It introduces many of the topics that are later dealt with in greater detail.

Chapter 1 is a sketch of major historical developments affecting the fisheries from the early 1800s through 1989. The picture, most simply, is one of initial abundance allowed by essentially unbridled harvesting of stocks and destruction of habitat as European immigrants crowded into California. Eventually, as near collapse of the fishery led tortuously toward development of protective legislation, California's commitment to statewide water development, principally to benefit agricultural interests, dealt fisheries a further blow. Competing statewide demands for water constitute the major problem today for those who would restore fishery resources. The historical sketch becomes detailed as it examines the greatly increased interest in salmon and steelhead resources of recent decades. In this review of landmark environmental legislation, both federal and state, we see how concerns for the subject are becoming central issues in California's precedent-setting environmental movement.

Chapter 2 discusses early Indian fishery problems on the Klamath River. Here Ronnie Pierce, a marine biologist and Indian historian, traces the changes that occurred in Native American life-

styles as the invasion by non-Indians into their territory—in which there were only two directions, upriver and downriver—destroyed tribal structures. One may see startlingly how a benevolent but bumbling federal administration attempted to convert native fisher tribes to an agricultural life-style, how a sometimes venal Congress concealed its refusal to ratify Indian treaties, and how questions of ownership and control of tribal lands became mired in legal issues that only now are being effectively resolved. Forced to adapt to new ways, Indians became fishermen and plant workers for non-Indian canneries, but because their gillnet fishing was declared to be the cause of declines in runs of Klamath River salmon, that canning operation was closed by law in 1933. Problems springing from this painful history have persisted over the years and continue to be sore points in negotiations between Indian and non-Indian fishers.

In Chapter 3, North Coast fish restorationist Scott Downie discusses salmon and steelhead in a vignette about early settler families on the South Fork of the Eel River. To them, as with the Indians, the fish were both a source of food and an attractive diversion from rigors of life in the sometimes harsh unsettled lands. By the early twentieth century, it was becoming apparent that the influx of new settlers was introducing a way of life, symbolized by the artificial flies they tied, that portended unwelcome change. In this selection, Downie also tells much about the biology of salmon and steelhead, suggesting how these species evolved in the special conditions of northern coastal California, which also produced dense mixed conifer and hardwood forests, in addition to the tall redwood groves found along the rivers.

In Chapter 4, an excerpt from his essay first published in 1944, Joel W. Hedgpeth views the earliest efforts of government in the 1870s to develop artificial propagation of salmon. This study, a classic of salmon lore, also acquaints the reader with the salmon fishery of a Wintu Indian village on the McCloud River, a northern tributary of the Sacramento. It describes how a retired Unitarian minister and avid chess player, Livingston Stone, fascinated with the new science of "fish culture," attempted unsuccessfully to help restore salmon runs in Atlantic Coast rivers by introducing chinook salmon from Pacific Coast stocks. The site of the village and the hatchery is now hundreds of feet below the surface of Shasta Reservoir.

Chapter 5, the final historical chapter, is George Warner's poignant account of how the San Joaquin River spring chinook run was made extinct in the late 1940s as the water of that river was shunted south to Kern County as part of the Central Valley Project. The reader shares the hopes and frustrations of weary Division of Fish and Game crews as they rig war-surplus equipment to save a doomed species while poachers lurk nearby, devising ways to capture fish when crews are not looking. Although local sportsmen-activists won temporary fish protection flows from harassed Bureau of Reclamation functionaries, the combination of federal power, state acquiescence, and the water lobby ultimately extinguished the San Joaquin spring-run chinooks and essentially destroyed the remaining salmon fishery on that stream.

Joel Hedgpeth and George Warner have added intriguing epilogues to their stories.

Chapter One—

Historical Highlights

Alan Lufkin

Salmon and steelhead have been significant anadromous fishery resources throughout California's history. The Native American people, totaling about three hundred thirty thousand individuals before the Europeans' arrival, depended heavily upon these fishes for subsistence, ceremonial, and trade purposes.

Early Indian Fishery

Indians of the Central Coast and in the Central Valley fished for salmon and steelhead found almost year-round in coastal streams and the Sacramento/San Joaquin rivers system. North Coast tribes, descendants of southerly migrating fishers, harvested these resources principally in late summer and fall months from the Eel, Klamath, Smith, and Trinity rivers and hundreds of lesser streams. It has been estimated that California's aboriginal peoples consumed or bartered about five million pounds of salmon per year. Salmon stocks functioned as a bank from which withdrawals could be made as needed: when other foods were in short supply, more salmon were taken. Tribal conservation practices, such as removing fish dams when adequate numbers of fish were taken, ensured that stocks would remain plentiful. No stream was too small to host populations of these hardy fishes; the commonly owned supply was endless. Methods of capture included several kinds of nets, spears, and a variety of wooden traps and weirs.

As highly valued resources, salmonid populations were the sub-

ject of Indian rituals and myths associated with the need to assure abundant runs throughout stream systems. The story of Oregos is one example. This helpful spirit in ancient times became a rock above the mouth of the Klamath River, where she told salmon about propitious weather conditions and warned them of dangers they must overcome. Today, when one thrills at the sight of salmon wildly pursuing anchovies below that rock, sometimes charging after individual fish for great distances along the surface, it is easy to dismiss the dictum that salmon stop eating when they enter the river. At that moment one may readily imagine that Oregos is telling the salmon to feed well on this, their last meal, as they prepare for their long and only upstream journey.

Immigrants Take Control

The period of non-Indian immigration and settlement during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was marked by a complex tangle of fishery-related matters. The subject is best presented in three overlapping perspectives: early development of the commercial salmon fisheries, effects of the gold rush and hydraulic mining, and early management efforts.

Commercial Beginnings

Early explorers and settlers of the westernmost frontiers were impressed with the quality and numbers of salmon and steelhead. Fremont ate "delicious salmon" at Sacramento. Bidwell and Sutter fished commercially, the latter employing Indian fishermen during the early 1840s. As part of the unexploited wealth of natural resources that drew immigrants to California, fish and wildlife initially belonged to no one and to everyone. Since the common resources seemed endless, harvest restrictions were unnecessary. Laissez-faire government encouraged exploitation of this cornucopia of resources for private gain and "public good."

In the absence of legal restraints, enterprising pioneers could fish almost as they pleased. In 1852 a state law enjoined "all good citizens and officers of justice" to "remove, destroy, and break down" any obstruction to salmon migration, except those erected by Indians. Other fishery laws soon followed, but such regulations

were not enforced. Efforts to protect the Indians and their fisheries were farcical.

During succeeding decades large-scale commercial fishing was developed. Informal but sternly enforced agreements within certain ethnic groups, particularly Italians and Greeks fishing the Sacramento River, became the fisherman's law. Arthur F. McEvoy, in The Fisherman's Problem, details how places to fish, kinds of fish, and harvest limits were controlled by fishing communities. Exclusions were also imposed: Chinese, for example, were not permitted to fish for salmon. In this ethos, an unplanned, rudimentary system of conservation emerged; maintenance of the fisher community way of life was an important consideration. Both the economic wellbeing of fishermen and the biological well-being of fish stocks benefited. Today, fishermen's leadership in salmon restoration endeavors, and festive events such as Bodega Bay's annual salmon festival and Fort Bragg's Fourth of July salmon barbecue, remind us that modern California's sophisticated salmon fisher communities still value this tradition highly.

Another segment of the non-Indian fisher group, however, felt no such restraints. The Atlantic salmon commercial fishery, long in decline, had essentially collapsed by 1860. One displaced fisherman, William Hume, crossed the continent with a homemade gillnet in 1852 and set it in the Sacramento River. Other East Coast fishermen followed Hume, seeking opportunities in western waters. These canny fishermen were able to obtain or thwart passage of regulations as their interest dictated. They openly defied laws they were unable to change. As ethnic differences broke down and market forces strengthened, this became the common pattern of San Francisco Bay/Delta salmon fishery "management."

The first West Coast salmon cannery opened on a scow moored near Sacramento in 1864. Within twenty years nineteen canneries were operating in the Delta area. In 1882 they processed a peak two hundred thousand cases of fish. (A case was forty-eight 1-pound cans.) On the North Coast, several salteries and canneries were operated by non-Indians. On the Klamath, Indian-caught fish were processed with Indian plant workers. Salted salmon from Humboldt Bay and Eel River ports, considered superior to the Central Valley product, found its way to markets in the Pacific Basin and New York.

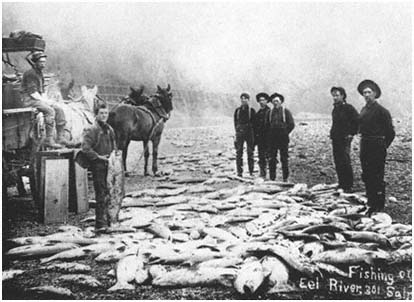

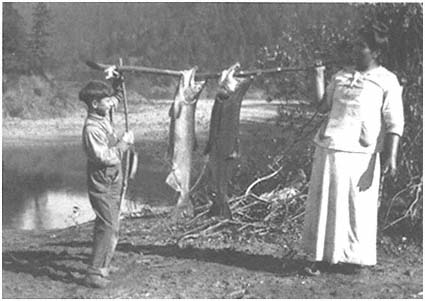

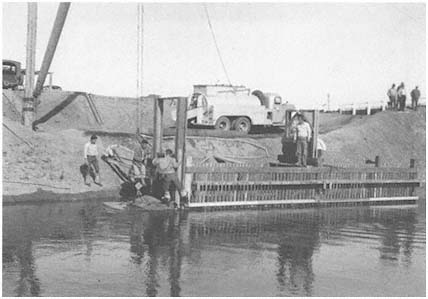

Choice salmon for everyone. Early twentieth-century commercial

seining operation on the Eel River near Rio Dell. Commercial salmon

fishing on the Eel began in 1851.

(Humboldt County Historical Society)

Hydraulic Mining Effects

The second factor affecting salmon and steelhead during this period was hydraulic gold mining, which began in the 1850s. By 1859, an estimated five thousand miles of mining flumes and canals were in use. Streams used by salmonids for spawning and nursery habitat were diverted indiscriminately for mining. Hydraulic cannons, up to ten-inch bore, leveled hillsides, so badly destroying stream habitat that salmonids could not survive. An estimated 1.5 billion cubic yards of debris (enough to pave a mile-wide super-freeway one foot thick from Seattle to San Diego) were sluiced into waterways and swept downstream, causing flooding and vast destruction of natural salmonid habitat as well as towns and farmland. The Yuba River bed near Marysville became a wasteland of rock piles, mud, and tangled masses of tree roots and branches two miles wide. Streambed elevations were raised—six or seven feet as far downstream as

Catches of salmon such as these were commonly taken

from coastal streams. The mottled appearance resulted from the fish

lying on stream-bank stones after capture.

(Peter Palmquist collection)

Sacramento. Extensive levees had to be constructed to protect riparian lands.

Although hydraulic mining was banned by federal law in 1884, the huge slug of mining debris severely impacted streams. Its effects can still be seen. Much salmonid habitat was permanently destroyed. After the 1882 peak canning year, the river net fishery experienced general decline, and the last commercial cannery in the Central Valley closed in 1919. A smaller canning operation on the Klamath was closed in 1933. Salmon stocks of the Central Valley basin were stressed beyond their resilience—the natural capacity to deal with environmental blows. The combination of overfishing and wanton destruction of habitat had reached the point at which the economic equation yielded less than zero to the commercial fishery.

While the river fishery declined, commercial trollers, noting the success of ocean sportfishers, began harvesting salmon offshore. By 1904, some one hundred seventy-five sail-powered fishing boats

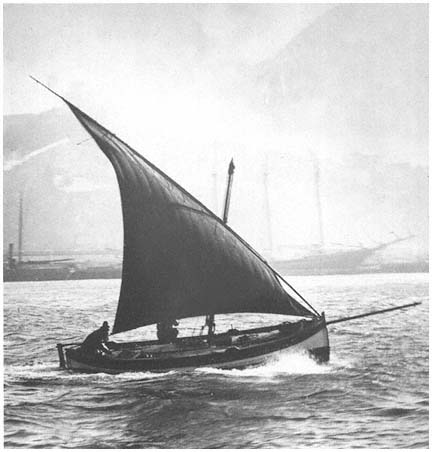

Lateen-rigged felucca, a type of fishing boat used by early Italian, and to

some extent Portuguese and Greek, fishermen on San Francisco Bay.

(National Maritime Museum)

were operating out of Monterey Bay. During the early decades of the twentieth century, as gasoline engines replaced sail power and revolutionized the industry, offshore commercial salmon trolling overshadowed river net fishing. This move to ocean grounds was seen by state fishery experts as the major reason why depleted salmon stocks could not recover. Fishermen fished huge areas over longer periods and brought to market catches of immature fish. Ocean fishing raised a host of regulatory problems to be resolved.

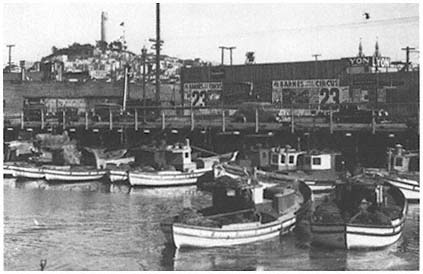

Montereys. The boats pictured in the 1930s at Fishermen's Wharf, San

Francisco, were powered by one-cylinder gasoline engines. The Monterey

replaced the sail-powered felucca in the

California commercial salmon fishery.

(National Maritime Museum)

Early Restoration Efforts

By the 1860s the social costs of essentially unrestrained exploitation of salmon resources were becoming obvious, but for the next half-century an unexplained phenomenon masked reality: the abundance of surviving stocks fluctuated dramatically. In 1878 salmon from the Sacramento River (which often accounted for 70 to 80 percent of the state's production, as it still does) were so plentiful that a twenty-five-pounder cost the consumer only fifty cents. As noted above, the Sacramento River salmon pack in 1882 peaked at two hundred thousand cases. By 1890 that number was a minuscule twenty-five thousand—one-eighth as many. By 1907, numbers had built to a twenty-year high, then faltered, rose, and fell again. The pack ultimately reached a low of three thousand cases in 1919—less than 2 percent of the 1882 high.

The reasons for the good years were many. After hydraulic mining stopped, its immediate effects gradually began to lessen. The State Board of Fish Commissioners, riding a worldwide wave of

interest in fish culture, was becoming a potent force in state fishery matters. Scientific study of fishery biology obtained strong governmental support. The Indian fishery produced less drain on the resource because Indians were driven off the rivers or their numbers were reduced by genocide or disease. Recurring sets of high runoff years provided abundant water for fish. It was even suggested that gravel from hydraulic mining improved fish spawning habitat in main river channels.

A number of possible reasons also explained the downside. Hydraulic mining was blamed initially, but by 1910 overfishing was considered the chief cause. These, however, were not the only reasons. Railroad construction in the upper Central Valley in the 1860s impaired salmon migrations on magnificent streams such as the McCloud; rock-blasting explosives also worked fine for killing fish to feed the nine thousand workers. After the demise of hydraulic gold mining, fish did not get back their water because miners' dams and flumes became farmland irrigation systems. Sea lions on San Francisco's Seal Rocks were blamed. Diverse ethnic groups pointed the finger at each other. Salmon protection laws were disregarded by stalwart citizens, including law enforcement officers, who resented state interference in local affairs. Polluted runoff from rice fields, fish diseases, sawdust from streamside mills—all were suspect. Debris dams built to contain the downstream creep of mining wastes often became the first barriers to upstream migrations of fish on larger rivers. Because environmental science was in its infancy, other unsuspected reasons may also have been at work, among them oceanic conditions, transplants of fish to nonnatal streams, or the effects of widespread introduction of exotic species like striped bass, shad, anti carp into Central Valley rivers.

In 1871 the American Fish Culturists Association, imbued with Darwinian zeal, persuaded Congress to establish a federal Fish Commission whose principal duty was to restore the nation's depleted fisheries. First among its California restoration activities was the establishment of a salmon hatchery on the McCloud River in 1872, from which eggs were to be transferred east to restore the Atlantic Coast salmon fishery. This measure soon led the California Fish Commission to initiate an ambitious state hatchery program. Also vigorously pursued was the passage of complex, ephemeral laws dictating how, when, and where fishermen could fish.

Enforcement problems persisted, with predictable effects: law-abiding fishermen suffered while lawbreakers caught more fish. In 1893 this problem was eased somewhat by the introduction of a commission-manned patrol boat, the Hustler, which prowled the Sacramento River day and night. Changes in court jurisdictions also helped. Despite such efforts, California's salmon resources early in the twentieth century continued to decline. The total commercial catch in 1880 was eleven million pounds; by 1922 it had dropped to seven million pounds; after great fluctuations it reached a low of less than three million pounds in 1939. Salmon stocks were depleted. Most fishermen had moved to better fishing grounds, but enough fish were left to support a marginal fishery—thus ensuring that stocks could not recover on their own. That was the classic "fisherman's problem" described by McEvoy.

Salmon and Water Interests

Agricultural water diversions have been devastating to fish life. Although farmers and fishermen were allies against miners, as that conflict ended the relationship changed. A law enacted in 1870 that required fishways around dams was never effectively obeyed, even though subject to periodic strengthening amendments. Presently, as Section 5937 of the California Fish and Game Code, it specifies in essence that water diversions must not interfere with fish migration. Nevertheless, many still do so. Section 5937 would seem unarguable; however, water diversion remains today as the most crucial issue facing anadromous salmonid fishery restoration efforts. Central Valley irrigation issues are the core of the problem.

The Central Valley Project (CVP)

While commercial fisheries faced serious problems at the turn of the century, plans to develop California's water resources, chiefly for flood control and firm irrigation, received close public attention. Five devastating floods during the years 1902 to 1909 led the legislature to seek federal help. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, active on California's water scene since 1868, conducted extensive debris removal projects in Central Valley rivers and, at state request, developed flood control projects in the Central Val-

ley. The Bureau of Reclamation, a federal agency that has made its mark on the West by building dams and distributing water, began studying water development potentials in California in 1905, focusing on reclamation of agricultural land.

The final result would be extensive development of irrigated agriculture in California. Both the corps and the bureau sought lead roles in that endeavor, but the bureau ultimately was placed in charge. In 1919 a proposal for comprehensive statewide irrigation development, the Marshall Plan, won lawmakers' approval. By 1931 this plan had evolved into an undertaking later called the Central Valley Project. State bonds could not be sold during the Depression, so California again sought federal help, and, in 1935, emergency relief funds became available for the project.

The Bureau of Reclamation began building Contra Costa Canal, the first unit in the vast project, in 1937. Friant and Shasta dams, southern and northern mainstays of the plan, obstructed fish passage in the early 1940s. Friant extirpated the already impaired San Joaquin River as a viable salmon stream. After construction contracts were let for Shasta, the Bureau of Reclamation commissioned a blue ribbon panel of fishery experts to study possible problems and propose solutions for salmon when they butted against concrete barriers. The resulting document, the Shasta Salvage Plan, provided for a broad range of structures and procedures to save the several stocks of Sacramento River chinook salmon. Heavy reliance was placed upon natural river propagation. Of many elements in the plan, only the fish trap at Keswick Dam, below Shasta, and Coleman National Fish Hatchery were successfully implemented and remain in operation today. Other elements were not started, were started but never completed, or were completed but did not work.

Irrigation, power production, and flood control were the major purposes of the Central Valley Project. Maintenance and improvement of fishery resources were among several subordinate purposes. While the postwar stage of the project was taking shape in the mid-1940s the Bureau of Reclamation's comprehensive planning documents, published in The Central Valley Basin, touted the "highly successful" Shasta salmon salvage program as a model for the future. Potential effects on fisheries were considered in discussions of several project elements. A letter of transmittal from Secre-

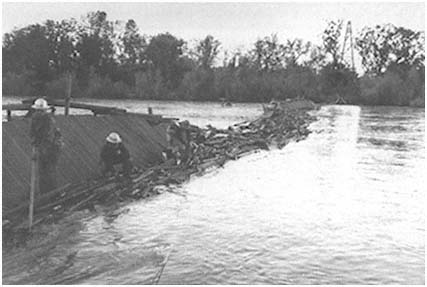

Best intentions weren't enough. High water in December 1941 washed out

the fish trapping facility at Balls Ferry on the Sacramento River. Rebuilt in

1943, it was abandoned as unworkable within three years. This structure

was part of the "Shasta Salvage Plan" to relocate salmon

displaced by the construction of Shasta Dam.

(Coleman National Fish Hatchery)

tary of the Interior Julius Krug to President Harry Truman gave assurance that "every effort will be taken to preserve fish and wildlife resources."

Many dams were seen as potentially favorable to fish life. The federal Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act (1934) to integrate water development with natural resource preservation ostensibly was in effect. Rosy predictions were made for future salmon runs on major streams affected by the project. If adequate fish protection measures were taken in planning and operation of project facilities, salmon runs then estimated at 250,000 could be increased to 640,000—a whopping 156 percent gain! The team of federal and state fishery experts making that prediction emphasized, however, that while potentially devastating effects of dams on anadromous fish runs were well known, the efficacy of proposed salvage and enhancement plans had yet to be proved. At least four years of planning time were needed before construction.

This requirement conflicted with the bureau's "first-things-first" philosophy. While engineers enjoyed the luxury of solving their problems on paper beforehand, fishery experts were required to apply virtually untested concepts. Bureau policy was clear: water and power came first. Fishery protection measures would be included in project facilities if they could be accommodated with minimal effect on major objectives. The concerns expressed by fishery experts were duly reported but had little effect on construction or operation of the CVP.

To well-meaning BuRec functionaries trying to accommodate diverse constituencies, the process was routine: priorities had to be established; some special-interest groups had to accept less than they demanded. Wartime pressures to complete the Shasta power facilities, coupled with material and personnel shortages, diverted attention away from fisheries. Bureau policy thus made fisheries expendable. While national emergency restrictions could partly explain the bureau's earlier neglect of fishery values, that excuse was invalid. Had the bureau genuinely acknowledged fish and wildlife values, fish protection planning could have begun with preliminary engineering studies and been realistically paced throughout the planning process. That did not happen.

The federal Bureau of Reclamation is widely blamed for subsequent fishery declines traceable to the CVP, and with reason. The agency gave lip service to fishery conservation causes, but its actions belied its words. The Shasta Salvage Plan failed. The San Joaquin fishery died. Trinity River salmonid stocks have been decimated. In recent years bureau policy appears to be changing, but most likely cosmetically. The bureau's primary mandate to provide agricultural irrigation water precludes major improvement of fisheries.

The State's Role

Less well recognized is the state's role in Central Valley Project fishery issues. Fishery professionals of the state Department of Fish and Game and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have worked together over the years to try to protect and improve fish resources. Their efforts have been seriously limited, however, by legal, political, economic, and social constraints.

Two events during the 1950s demonstrate the kinds of prob-

lems they encountered. The first was a federal court case, Rank v. Krug . In 1951, when farmers, duck hunters, and fishermen were suing the federal government to increase flows in the San Joaquin River below Friant Dam, California Attorney General Edmund G. ("Pat") Brown, at variance with a related finding of his immediate predecessor, declared that "the United States is not required by State law to allow sufficient water to pass Friant Dam to preserve fish life below the dam." The federal government was exempt from "state interference."

The second, closely related, event was also a blow to fishery interests. It involved the June 2, 1959, decision (D 935) of the California Water Rights Board, which declared that salmon protection on the San Joaquin River was "not in the public interest." This 1959 decision merits closer examination because it further reveals the collaborative nature of state and federal political mechanisms involved in both cases. In the 1930s and early 1940s, when Friant Dam was planned and constructed, the Bureau of Reclamation had not acquired water rights related to that project. During the late 1950s, when the bureau initiated the process of establishing those rights, state Fish and Game staff decided to reopen the legal question involving water for salmon in the San Joaquin River. The department, through Jack Fraser, its chief of the Water Projects Branch, filed protests with the Water Rights Board to justify its claim. That move stirred the water development community to action at every level.

First, the attorney general declined to represent the Department of Fish and Game, claiming that his office foresaw conflict of interest problems if it were asked to represent both the Department of Fish and Game and later, if there were appeals, the Water Rights Board. After much wrangling and foot-dragging, the attorney general authorized the department to employ outside counsel to represent it at the hearings but then balked at providing adequate funding for the purpose. Fraser searched intensively and finally settled on Wilmer W. Morse, a former deputy in the attorney general's office at Sacramento and recognized expert in judicial review of administrative procedures. Realizing that all adverse decision by the Water Rights Board could be expected, Morse and Fraser concluded that their efforts should focus on laying the groundwork for a successful appeal.

During this period, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sought vigorously to enter the case in support of state Fish and Game. The Department of Interior denied the service's request on the grounds that "it would not be in the best interest of the United States for an agency of this Department to support the position of the Department of Fish and Game."

In January 1959, Pat Brown became governor. He appointed veteran Bureau of Reclamation waterman William E. ("Bill") Warne as his director of the Department of Fish and Game. The June 1959 decision, as expected, was adverse. At that point, Morse and Fraser, with approval of Director Warne, devoted themselves to preparing an appeal (petition for judicial review), required to be filed within a thirty-day period. It would include an allegation that Brown and former Water Rights Board Chairman Henry Holsinger had acted to circumvent fish protection laws in 1951 when Brown as attorney general, with Holsinger's participation, had issued the "no state interference" opinion in favor of the bureau. Plans for the court action became known outside the department, and a delegation representing concerned Friant water users, the bureau, and the State Department of Water Resources insisted that Brown prohibit the Department of Fish and Game from filing the court action.

Just hours before the deadline, while mimeographed copies of the voluminous document were being stapled together, Governor Brown's secretary informed Morse that the governor had decided the case should not be filed. Morse insisted upon talking face-to-face with Governor Brown. The governor saw him at once, listened attentively, but declined to change his position. At the Department of Fish and Game, Jack Fraser, "furious as well as heartbroken," sought help from Director Warne, only to learn that "the door had been slammed shut, . . . William Warne was firm—the Governor's office had issued the edict, and that was it!"

Thirty years later, Jack Fraser recalls, "It was the low point in my career. I could not comprehend the crass circumvention of the public interest and destruction of public resources by purely political edict."

After serving for nine months as Director of Fish and Game, Warne was named state director of agriculture for a year. In January 1961, Governor Brown put him in charge of the Department of Water Resources.

In February 1989, UPI newsman Lloyd G. Carter reported an interview in which the octogenarian Pat Brown explained that he had always tried to balance the needs of salmon against other demands for water, adding, "We wanted to build the California Water Project and then work with the Bureau of Reclamation, and so I didn't want any confusion about it." (Funding for the State Water Project received voters' approval by a narrow margin in 1960.)

Despite Pat Brown's expressed intentions, the confusion engendered by those decisions of many years ago may not have been allayed permanently. The many complex issues of the bureau's Friant water contracts are being reexamined in a lawsuit initiated in 1988 by a consortium of conservation and fishermen's groups.

The Postwar Period

The Good News and the Bad

At the close of World War II, optimistic predictions for renewal of salmon runs in Central Valley rivers appeared to be coming true. Great volumes of cold water released from Shasta Reservoir were a boon to upmigrant adult fish, and ample flows assured their seaward-bound progeny safe downstream passage to the Pacific Ocean. Streams feeding the lower San Joaquin River were packed with salmon. In the upper Sacramento River, tourists at Redding Riffle watched the dark backs and thrashing tails of thousands of spawning chinook salmon. So crowded were successive runs of fish that new arrivals often uncovered redds of earlier spawners. Hungry steelhead and other fish consumed untold numbers of developing salmon eggs that were thus swept downstream.

Commercial fisheries prospered from this cornucopia. During the war, a cycle of favorable weather years promoted salmon survival, although fishing pressure increased. In 1939, commercial fishers had caught less than three million pounds of salmon; by 1945 and 1946 the number exceeded thirteen million. The commercial salmon fishing industry was coming back.

Sportfishermen also fared well. During the 1920s northern California's salmon and steelhead streams had earned worldwide acclaim, and the economic value of the sport fishery exceeded commercial fishing by two-to-one. In the mid-1930s ocean party-boat

fishing began to gain public favor; between 1947 and 1955, that commercial-cum-sport industry skyrocketed, reporting 1955 landings of one hundred thirty thousand salmon—five hundred percent more than were reported just six years earlier.

It was indeed too good to be true. Large runs of salmon gathered at Redding Riffle in such abundance because impassable dams stood between them and their ancestral spawning grounds. Without choice, they spawned wherever they could. Of broader significance, irrigation contracts for Shasta water had not been let; thus, ideal stream conditions would exist for only a limited time. Future generations of those spawning fish would return to far less promising habitat and flows.

Water projects took on renewed life in the early postwar decades. In 1951, when snowmelt from Mount Shasta at last began watering farm fields in the San Joaquin valley, the legislature authorized studies for the State Water Project (SWP). Oroville Dam on the Feather River would be the system's key facility. The major purpose would be the transfer of northern California water south to Kern County and south coastal California for agricultural, industrial, and domestic use. Some two dozen other water districts up and down the state, thanks to their representatives in state government, also stood to benefit. Massive diversions would ensure that little water would "waste to the sea," an expression that became the shibboleth of SWP promoters. Construction began in the early 1960s.

An ironic note in the story of Sacramento River basin salmon: river gillnetting was banned in 1957, not for the welfare of salmon, but because of protests from striped bass fishermen. Gillnetters had to throw back incidental takes of stripers, and fishermen objected to seeing dead fish floating by, especially when their own luck was bad, so all river gillnetting was stopped.

Throughout the period the Bureau of Reclamation continued its Central Valley Project activities. In the mid-1960s the interbasin transfer of 90 percent of coastal Trinity River's water to the Sacramento basin was completed. The Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation built dams on the American River. Hatcheries, with improved planning because of the strengthened federal Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act, were constructed at these diversions to mitigate lost fish habitat.

The Red Bluff Diversion Dam

In the mid-1960s the Bureau of Reclamation built the Red Bluff Diversion Dam on the Sacramento River. Working cooperatively with the state Department of Fish and Game and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the bureau incorporated an elaborate fish protection and enhancement facility into that irrigation project to mitigate lost spawning habitat. In lieu of a hatchery, the bureau constructed a state-of-the-art system of artificial spawning channels with accompanying fish screens, controlled water flow, and thousands of yards of ideal-sized spawning gravel.

At the dedication ceremonies, the late Vernon Smith, a spokesman for sportfishermen, happily told the festive group that this was a truly historic occasion. At last fishery and water interests, recognizing and honoring mutual concerns, had embarked on a positive, promising endeavor. The crowd clapped and cheered.

Citizen Action Begins

The First Advisory Committee.

Commercial salmon catches after the first postwar years rollercoasted down by more than half, rose dramatically to twelve million pounds in 1955, then again plummeted to less than four million pounds in 1958. Erratic fluctuations marked the following decade's below-average catch figures. A host of factors—from economic forces to weather and ocean conditions, including possibly normal fluctuations in salmon populations—made the immediate causes difficult to pinpoint. The Department of Fish and Game concluded that the principal threat to salmon stocks was the declining survival rate of young fish and in 1968 announced a plan to reduce sportfishing bag limits, close some areas to fishing, and shorten the season. Further steps in 1969 would include curtailing the commercial fishery season and intensifying hatchery production and screening of major water diversions.

During that time, environmental activism was becoming an accepted American phenomenon. The California Environmental Quality Act (1970), the National Environmental Policy Act (1970), and later the California Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (1972) were among the dozens of legislative products of that movement. When the Department of Fish and Game announced its plan to further restrict

harvest, alert fishermen-activists felt wronged. The department had emphasized that overharvesting was not the cause of the decline, so why should fishermen suffer the consequences? Commercial salmon fishermen were already being forced to sell their boats, a painful and unfair way to learn conservation imperatives.

Historically, government bureaucrats tend to see fishery management as a simple supply and harvest proposition, but salmon regulations always seem to emphasize restrictions on the harvest. Why not do something about the "supply" side—restoration of suitable natural spawning and rearing habitat? Under the leadership of William Grader, a Fort Bragg fish processor, commercial fishermen successfully petitioned the legislature to create a citizens' advisory committee to study causes of salmon and steelhead declines and recommend remedial action. The California Department of Fish and Game and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agreed to provide consultant services.

The 1971 report of the Salmon and Steelhead Advisory Committee, titled An Environmental Tragedy, aimed at reversing the declines and insisted that the Department of Fish and Game place highest priority on restoration of natural habitat. (Today hatcheries contribute about half of the total salmon production.) The legislature was urged to assure adequate and equitable federal and state funding and to guarantee that future projects affecting the resources would include fish protection as a purpose. In a special section dealing with the Bureau of Reclamation's Trinity River Division, the committee noted that Trinity steelhead runs had declined 82 percent since 1961 and urged priority action to correct the faulty technology contributing to the failure.

The second report, A Conservation Opportunity, published in 1972, expressed satisfaction that the legislature and Fish and Game had already acted favorably on eight of nine committee recommendations aimed at restoring salmonid resources. The report then detailed opportunities for state and federal governments to take further restoration steps. Amendments to various federal acts dealing with water and power projects were addressed. The group also recommended that the federal government should make up fully for past neglect of fishery protections in Central Valley Project works.

The 1975 report of the Advisory Committee, titled The Time Is

Now, emphasized the need for local initiative and suggested ways in which state and federal governments could contribute to this effort. Reporting disease problems and other failures of hatcheries (the Nimbus Hatchery had just lost seven million fingerlings to disease) and expressing concern that the Red Bluff Diversion Dam spawning channels were not producing hoped-for results, the committee reemphasized an earlier suggestion: development of off-stream rearing ponds.

Hatchery operations often produced surpluses of young salmon and steelhead that had to be released directly into streams, where few survived. The citizens' group suggested that these fish be made available to local communities for nurture in offstream rearing ponds, then released into streams to migrate freely to the ocean. The concept had been tried on California's North Coast, where it generated keen interest among conservation organizations, industry, and the general public. The department liked the idea and volunteered to provide technical expertise. The legislature provided start-up funding and later established more substantial fishery restoration accounts. Offstream rearing projects have since expanded on coastal watersheds with promising, but debatable, results. Fishery experts raise serious questions about the genetic implications of the practice.

The Upper Sacramento Committee.

Despite follow-up action related to the citizen committee's recommendations, salmon runs in the Sacramento River continued to decline. In 1982, Charles Fullerton, director of the Department of Fish and Game, appointed a citizens' advisory committee to explore salmon and steelhead problems on the upper Sacramento River, above the mouth of the Feather River. Salmon runs there had declined since the 1950s from four hundred thousand to fewer than one hundred thousand, and the percentage loss of steelhead was even greater. The Upper Sacramento River Advisory Committee has been characterized as a rifle aimed at specific problems, compared with the shotgun approach of the legislature's committee, which studied statewide conditions. Both committees benefited from expert consultant services provided by state and federal fishery agencies.

The first target of the Upper Sacramento Committee was Red Bluff Diversion Dam. In a well-documented report, the committee

labeled that facility as "perhaps the single most important cause" of the declines. The dam seriously obstructed upstream spawning migrations, caused the destruction of millions of seaward-bound juvenile fish, and, despite determined efforts of state and federal fishery planners, the mitigation facilities simply did not work. The committee recommended several steps to correct the migration problems, but it saw little hope for the artificial spawning channels. Abandon them, it concluded, and rework part as rearing ponds for juvenile fish.

Subsequent studies of the Upper Sacramento Committee dealt with problems of Coleman National Fish Hatchery and an Army Corps of Engineers bank stabilization project between Chico and Red Bluff. Their fourth report, in 1986, focused on the Glenn-Colusa Irrigation District's faulty fish screen operation, a longstanding problem that causes downmigrating fish losses estimated to equal the production of Coleman Hatchery. In essence, the committee recommended that federal and state agencies, employing existing legal mechanisms such as Fish and Game Code Section 5937 and the public trust doctrine, should force the water district to correct faulty conditions. If that did not work, the GCID gravel dam should be removed and pumping should be reduced or eliminated entirely. The committee's tough position is supported by a host of conservation-minded fishery groups, including the United Anglers of California, a politically powerful group representing thousands of various sportfishermen. The matter is currently being debated at state and federal levels.

The imminent possibility that the winter run of chinook salmon in the Sacramento River will become extinct commanded the attention of the Upper Sacramento River Advisory Committee in 1988. This unique race, its roots intertwined with fish that railroad crews blasted in the McCloud River in the 1860s, had declined in numbers from one hundred and seventeen thousand spawners in 1969 to fewer than twelve hundred fish by 1980 and remains at a precariously low level. Actions by the American Fisheries Society and a local conservation organization to have this run declared a threatened species ultimately led to development of a joint state/federal restoration plan. The Advisory Committee evaluated this plan in 1988. While recognizing its potential strengths, the committee decried the lack of progress in putting it into effect

and determined that the planned program was legally unenforceable and administratively weak. The committee's recommendation: the winter-run chinook salmon of the Sacramento River should be listed as endangered or threatened under both federal and state endangered species acts.

Current Indian Fishery Issues

Citizen action related to salmon during the later postwar period extended beyond traditional sport and commercial fishermen's concerns. North Coast Indians were keenly aware of potential tribal benefits inherent in the environmental movement. Encouraged by their respected elders, they reminded non-Indians that the economic well-being of tribes in the Klamath/Trinity watershed had been irreparably damaged by the 1933 closure of the Klamath River commercial canning operation. They determined that such a debacle must never recur.

Although the Hupa and Yurok tribes had for some years experienced unresolved internal strife over timber sales, fishery issues unified them with the upriver Karoks toward one goal: economic development of the Klamath basin, with strong Indian write in management. Since the Central Valley Project's Trinity River Division had hurt both river and ocean salmon fisheries, non-Indians shared Indians concerns, but they did not welcome possible Indian control of the fishery.

During the 1970s Indian determination to realize their goal led to a series of state and federal court decisions that in effect established Indian rights to fish in traditional ways and compete with non-Indians in the commercial salmon fishery. With the passage of the federal Fisheries Conservation and Management Act in 1976, strife between Indian and non-Indian commercial fishers reemerged.

Results

Governmental positions relative to fish and wildlife issues from the early 1970s to the present have switched noticeably for a variety of reasons. First was a growing popular awareness that effective government requires citizen involvement. The 1950 Rank v. Krug case was often cited as an egregious example of governmental giveaway

of natural resources. Its sequel, the 1959 stance of the state Water Rights Board that San Joaquin salmon conservation was not in the public interest, seemed unbelievably callous. Even the Bureau of Reclamation, structural specialist, was discussing "nonstructural" solutions to fish and wildlife resource problems.

Recent decades are notable for a plethora of governmental actions potentially beneficial to salmonid resources. Foremost was passage of the federal Fisheries Conservation and Management Act of 1976 (Magnuson Act), which extended federal control of the nation's fisheries from three miles offshore to two hundred miles, inaugurating an innovative system of federal/state fishery management. A new entity, the Pacific Fisheries Management Council (PFMC) with representatives from California, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington, was created to mediate fishery matters among user groups. Fish from the four states commonly range up and down the Pacific Coast and are targets of various commercial and sport fishermen. State governments had long dealt with resulting interstate problems and still maintain authority to three miles offshore. The Magnuson Act, through federal fishery agencies, gave the PFMC authority to resolve interstate and federal ocean fishery problems in a representative forum. PFMC's biological staffs also introduced computerized "preseason abundance forecasts" that missed the mark by as much as 300 percent and led to regulatory snarls involving allocation agreements between Indian and non-Indian commercial fishers harvesting Klamath River stocks.

Although its administration is still far from perfect, supporters of the Magnuson Act point to two of its benefits: better control of foreign fishery competition and a comprehensive resource-oriented approach to ocean fishery management that will, in the opinion of many professionals, ultimately benefit fish and fishers alike. In the meantime, the offshore troll fishery has been seriously affected.

Inclusion of several rivers, principally along the North Coast, in the California Wild and Scenic Rivers System (and later their further protection under federal law) was a widely accepted victory for conservation-minded Californians. Such actions affirm growing public recognition that maintenance of fishery and other wildlife values qualifies as the highest use of these aquatic resources. Among other encouraging governmental acts of the period were passage of the Forest Practice Act to lessen environmental damage from logging

(1973); announcement of the state Resources Agency's goal to double salmon and steelhead stocks (1978); establishment of the Renewable Resources Investment Fund (1979); the California Environmental License Plate Fund (1979); inauguration of the Salmon Stamp Program, a highly successful commercial fishermen-funded salmon and steelhead restoration program (1982); and coordination of operating procedures for federal and state water projects (1985). Also introduced were a program limiting new entries in the commercial salmon troll fishery, completion of a fishery agreement between the state and Indian tribes, strengthened provisions for fish and wildlife protection in water project planning, and a number of additional funding bills.

At the federal level, Congress in 1984 authorized a $57 million ten-year Klamath/Trinity fishery restoration project, and a total of $2.5 million (about one-tenth of the needed amount) was provided for renovation of Coleman National Fish Hatchery. Improvement of fish passage facilities at Red Bluff Diversion Dam were also funded; although initial results were encouraging, detailed evaluation in October 1988 revealed that major additional structural and operational improvements were needed to ensure lasting benefits.

Less popular among fishermen was the 1972 passage of the Marine Mammals Protection Act. Seals and sea lions intercept upmigrant adult fish at river mouths and tear hooked salmon off fishermen's lines in the ocean. Fishermen see this increasingly as a threat to their fisheries. Frontier-style controls are no longer tolerated, and populations of these marine mammals are expanding rapidly. Conservationists point out, however, that this relatively minor "threat" must not be allowed to divert attention away from bigger problems, such as loss of habitat that may cause total extinction of some species.

In 1988 a citizens' initiative, The Wildlife, Coastal, and Park Land Conservation Act (Proposition 70), received voters' approval. This act provides $16 million to restore, enhance, and perpetuate salmon, steelhead, and wild trout resources throughout California.

Perhaps the most significant governmental act of the period, at least potentially, was the Racanelli Decision in June 1986. The following description of this monumentally important court decision is offered by William Davoren, executive director of the Bay Institute of San Francisco:

Named after P. J. Racanelli, the presiding justice of the First Appellate District, State Court of Appeal, the decision was accepted by the State Supreme Court in September 1986. The case grew out of appeals of the State Water Resources Control Board's 1978 water rights order (D. 1485) and water quality plan for the Delta and Suisun Marsh.

Racanelli established that the State Board must consider all water users of the Sacramento/San Joaquin system, not just the big federal and state projects, and called on the Board to apply public trust doctrine principles as established by the Supreme Court in the Audubon—Mono Lake precedent.

The decision sharply criticizes the Board for giving too much consideration to water rights and failure to give enough consideration to its responsibilities for protecting fisheries and water quality. The timing of the decision seriously affected the Bay-Delta Hearing, now under way, that is scheduled to end in July 1990 with a new order and water quality plan replacing the interim standards of 1978.

Too Much Help?

Legislation and other public support during recent years introduced an ironic element: fish and wildlife offices were unprepared to deal with the new opportunities. It has been a period of confusion. The Department of Fish and Game developed no comprehensive salmon and steelhead management plan because it lacked sufficient data about the resources and was unable to hire needed personnel because of a hiring freeze in state government. No coherent plan for evaluating outcomes of restoration efforts existed. Overtaxed enforcement personnel were unable to monitor compliance with new laws. So many public bodies had an interest in salmon that interagency coordination of planning and restoration efforts had to be crafted on an ad hoc basis.

In 1983, California's governor, George Deukmejian, announced his intention to appoint as new Fish and Game director a woman considered by environmental groups and some legislators to be obviously unqualified for the position. Although this action was soon rescinded, it signaled the governor's lack of concern about natural resource conservation. Water developers sensed renewed freedom, and federal water brokers, advertising surpluses, sought additional Central Valley Project customers.

Also that year, a natural disaster compounded fishermen's woes. A periodic air and oceanic condition called El Niño developed. The

upwelling of Pacific Ocean waters that supplies rich nutrients to make California fishing grounds so productive suddenly ceased. The ocean became eerily clear, salmon all but disappeared, and the few that were caught were as thin as snakes. The commercial catch dropped to the lowest ever—less than 2.5 million pounds, down 70 percent from 1982. Nineteen eighty-three was a bad year for salmon and the salmon fisher community.

Recent Citizens' Actions

Fishery leaders, in a forum (now the annual "Fisheries Forum") established by the legislature's Joint Fishery and Aquaculture Committee, called for reestablishment of the Advisory Committee on Salmon and Steelhead Trout. The legislature concurred and charged the committee with responsibility for developing a comprehensive statewide plan for management of these resources.

Representatives of commercial and sport fishermen, fishery biologists, Native Americans, and the general public were appointed to the committee. With initial financial and staffing help from the Department of Fish and Game (and later full funding by the legislature), it divided the state into eleven basin study areas and recruited hundreds of local citizens and professionals to determine the status of salmonid resources and recommend restoration programs. Simultaneously it initiated in-depth studies of common problems such as lost and degraded habitat, economic pressures, lack of public education, insufficient and polluted water, and a half dozen others.

The committee's work was reported in three publications: The Tragedy Continues (1986), A New Partnership (1987), and Restoring the Balance (1988). The earlier publications reported committee planning and progress toward meeting its charge. The 1988 report urged official state commitment to doubling of salmon and steelhead stocks and listed more than a hundred findings and recommendations pointing the way toward realization of that goal. The most urgent recommendations included strengthening the California Forest Practice Act and enforcement of streamflow requirements for fish and wildlife. Also emphasized was the need for legislative action to halt further federal water marketing efforts until the

current Bay/Delta water quality studies by the State Water Resources Control Board are completed.

The Advisory Committee also recognized the urgent need to build public awareness of its concerns. Toward that end, it financed initial development of a public school education program and a professional-quality videotape, On the Edge, focusing on salmon and steelhead, and encouraged preparation of this volume. It also developed a plan to utilize the legislature's resources to make the committee's voluminous findings and reports publicly available at low cost.

The 1988 report led to several legislative initiatives, the most significant being SB 2261, the California Salmon, Steelhead Trout, and Anadromous Fisheries Program Act. This legislation required the Department of Fish and Game to "prepare and maintain" a comprehensive salmon and steelhead conservation and restoration program, coordinating its activities with the Advisory Committee. Doubling of California's salmon and steelhead stocks by the year 2000 was declared to be state policy. Funding included $250,000 for Department of Fish and Game start-up costs. During the fall of 1988, the Advisory Committee began defining its monitoring responsibilities relative to the plan; in 1989, it began working with the Department of Fish and Game toward its implementation.

In other ways, as well, the "winds of change" that Stuart Udall, a former head of the Department of Interior, heard blowing during an earlier administration were clearly felt during 1988 and 1989. In 1988, the California commercial salmon fishery landed a record 14,671,400 pounds of salmon. The ocean sports catch exceeded 200,000 fish, slightly below 1987 figures. Other "good news" was the determination by federal and state authorities that the Sacramento River winter chinook run qualified as an endangered species, thus deserving of extensive, not yet fully determined, protective measures. The State Water Resources Control Board issued a draft plan for control of Delta water quality that included provisions favorable to fish life and suggested the need for a statewide "water ethic" that could necessitate a definition of "reasonable use" favorable to fish and wildlife resources. The Bureau of Reclamation acknowledged water temperature problems at Shasta Dam and announced development of a plan to provide plastic curtains to help

cool water releases. The problem-plagued Red Bluff Diversion Dam spawning facilities were closed.

These developments were tempered, however, by a number of sobering facts: in 1989, a precariously low number of Sacramento River winter chinooks—five hundred and seven—returned for spawning at Coleman National Fish Hatchery. The eggs of only one pair were successfully hatched; some fish, however, spawned naturally in the river. The cost of installing controversial water temperature control curtains at Shasta Dam, initially estimated at $5 million, which Congress appropriated in 1988, was recalculated at about three times that amount. A more conventional—and more expensive ($50 million)—temperature control system recommended by engineers is now being considered. Questions of who should pay for it—the Bureau of Reclamation or fish and wildlife agencies—are being debated.

Klamath Management Zone Problems

Problems within the Klamath Management Zone (KMZ) continued, and commercial troll fishermen were restricted in 1988 to a total of 40,450 fish. That harvest quota was reached within a few days of season opening, whereupon the KMZ commercial troll season was closed and the sport fishery bag limit was reduced to one fish. A distressing "Catch 22" situation developed in that fishery, as it became apparent that successful efforts to improve conditions for Klamath salmon survival led unintentionally to the lowering of harvest quotas. The reason: the increased numbers of Klamath fish in the mixed-stock ocean fishery increased the "Klamath contribution rate," a key element in PFMC's determination of harvest quotas in the KMZ fishery. Thus, the greater the percentage of the protected Klamath fish in the zone, the lower the total number of fish available for harvest in the entire zone. Because Klamath salmon mix with salmon in ocean zones north and south of the KMZ, restrictions were also placed on those fisheries; the impact was felt by Fort Bragg fishermen and those further south, who harvest principally salmon orginating from streams entering San Francisco Bay.

The 1989 KMZ troll fishery—with a 30,000 fish quota—was open for a longer period, but there was a twenty-fish-per-day limit to

discourage larger "trip boats" from competing inequitably with smaller "day" boats. Fishing south of the zone initially was so poor, however, that the trip boats moved north and fished the Klamath zone anyway. The 1989 commercial troll catch dropped to five million pounds of salmon.

Because of complexities such as these, commercial trollers balked at spending "Salmon Stamp" money to support Klamath River artificial propagation improvements. Moreover, the trollers claimed that contribution rate figures revised upward by the PFMC violated preseason agreements. The state Advisory Committee, meeting in June 1989, scratched their heads over what should be done about a situation in which, as one member termed it, "more is less."

Water Issues

Nineteen eighty-eight was a second consecutive drought year, and until March 1989 a third such year appeared to be in the making. Because of this and other coinciding factors, control of water resources dominated California fishery and other environmental news during the period.

SWRCB Bay/Delta Salinity Plan Development

The Bay/Delta water quality issue before the SWRCB reached crisis level in January 1989, when the board's Phase II draft plan released just two months earlier elicited strong opposition from water development interests, who vowed to "fight this every way we can."

The draft plan was a disappointment to fishery interests as well because it lacked fish flow assurances for dry years and promised little hope for recovery of San Joaquin River salmon runs. It did include provisions for increased spring flows and reduced Delta pumping, however, and was grudgingly accepted. Central Valley and southern California water interests objected to the draft plan because of the fishery considerations and other reasons, and they succeeded in disrupting the board's schedule for development of a final plan.

In January 1989, the SWRCB announced a six-to-twelve-month

delay in the hearing process to provide time for further studies. The board also removed the increased spring flows from consideration in Phase II of the hearings and sought additional input from interested parties. In April 1989, the SWRCB announced that a revised draft plan would be released for public review in late 1989 and offered assurances that the revision would consider the provisions of SB 2261, the anadromous fish protection law sponsored by the Salmon and Steelhead Advisory Committee, to be an expression of state policy. Fishery activists anticipate that the question of increased flows and reduced pumping from the Delta, however, will remain contentious issues. Final elements of the plan are now scheduled to be completed by 1993. The original target date was mid-1990.

Renewal of Friant Water Contracts

Renewal of forty-year-old water contracts between the Bureau of Reclamation and San Joaquin Valley water districts also became a prominent issue. On December 21, 1988, the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and twelve (eventually thirteen) other environmental groups sued in federal court to force the bureau to review environmental impacts under the National Environmental Policies Act prior to the precedent-setting renewal of the expiring water contract with Fresno County's Orange Cove Irrigation District. Six days later, the bureau announced it would renew the Orange Cove contract, purportedly in keeping with 1956 reclamation law. The bureau's position, enunciated by the Department of Interior's solicitor, Ralph Tarr, was that since no major changes were involved, "mere renewal" did not require environmental review.

Following pleas from the NRDC-led group, and several members of Congress who asked President-elect George Bush to help resolve the matter, the Justice Department agreed to delay signing of the contracts for a month. At that point, the Environmental Protection Agency, unable during the prior year to convince the bureau that environmental reviews were required before contract renewals, requested the president's advisory Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) to intercede. CEQ held hearings in Washington, D.C., and Fresno during April 1989 mid on June 30 recommended that major environmental studies must precede contract

renewals. It also explicitly expanded its review, recommending that the bureau conduct studies "for each of the water service units of the CVP prior to the renewal of the individual long-term contracts in that unit."

Federal District Judge Lawrence Karlton, hearing the NRDC lawsuit in Sacramento, initially enjoined the bureau from renewing the Orange Cove contract, but he later permitted temporary renewal pending outcome of the suit. In April, Secretary of Interior Manuel Lujan, declining to wait for CEQ recommendations, granted the Orange Cove contract and indicated he would renew another twenty-eight contracts before CEQ studies were finished. The increased price—from $3.50 to $14.84 per acre-foot—in the new contract would, he believed, "do more for conservation than all the courts." Several hundred more contracts will be expiring in coming years. CEQ's findings will influence the outcome of the suit. A court ruling favorable to the environmental groups could void all of the renewed contracts.

As suggested above, and confirmed by other recent developments, water economics—specifically water marketing—is coming to the fore as a key factor in California's ongoing struggle over control of water resources. The potential effects of this development on the state's salmon and steelhead stocks cannot yet be predicted.

Asian Driftnet Concerns

The Asian (Japanese, South Korean, Taiwanese) high seas driftnet fishery in the North Pacific also caused concern because of its possible effects on migrating California salmonid stocks. Careful study and monitoring of the operation has established that Northern United States, Canadian, and Soviet fish and wildlife populations have been seriously harmed by this fishery. Although California coho and chinook salmon stocks are felt to be unaffected because they generally range south of the driftnet operation, alarming evidence emerged in 1989 suggesting that California steelhead stocks are being hurt.

Richard J. Hallock, retired DFG marine biologist, prepared a study for the Upper Sacramento Salmon and Steelhead Advisory Committee which revealed that steelhead from at least five Califor-

nia streams—from Humboldt County's Van Duzen River to Carmel River on the Central Coast—migrate through the high seas driftnet area. A significant proportion of the state's steelhead population—as much as 10 percent annually—may be lost to that fishery.

Despite successful enforcement efforts of the National Marine Fisheries Service and the U.S. Coast Guard, resolution of the problem promises to be difficult because it impinges on international trade relationships. Federal law and international fishery agreements have only limited effect. In August 1989, the California Department of Fish and Game announced its participation in development of a coordinated coastwide plan to curtail the destructive effects of the high seas driftnet fishery.

A Future in Doubt

As California enters the final decade of the millennium, the status of its salmon and steelhead restoration efforts is at a critical point. Improvements are apparent: public funding is being provided; habitat restoration projects are progressing; public awareness is increasing. Long-range successes, however, will be crucially affected by legal developments such as the result of the Friant water contracts suit and the final outcome of a March 1990 ruling of the U.S. Court of Appeals in San Francisco that upheld the constitutionality of the Reclamation Reform Act of 1982. (The reform act restricted the use of subsidized water from federal reclamation projects to nine hundred and sixty acres per farm.) The initial effect of such legal developments is establishment of a level playing field. Until success is achieved in that realm, and ecological principles become broadly accepted, the future of California's salmon and steelhead will remain in doubt.

Chapter Two—

The Klamath River Fishery:

Early History

Ronnie Pierce

"The present is the living sum total of the past." This observation applies directly to an understanding of the Indian fisheries of northern California's Klamath River. Two distinct pasts of the indigenous river people, the precontact and the postcontact eras, have merged to create the complex tangle of tribal values, economic realities, political, legal, and environmental concerns that exists today. To understand the current status of the Indian fishery, the controversy, and the confusion surrounding Indian fishing rights, one must understand both of these pasts.

Precontact Era

The aboriginal territory of the Yurok people encompassed riparian lands along the lower forty miles of the Klamath River, from its confluence with the Trinity River, its major tributary, to the Pacific Ocean. It also included coastal lands from a few miles north of the river's month south to Trinidad. The Yurok people have lived and fished on the Klamath River from time immemorial. The river was their world. North, south, east, and west did not exist for them. The only directions were upriver or downriver. The center of their world was Qu'-nek, where the Klamath joins the Trinity.

As the Yurok world centered on the river, the peoples' lives centered on its fish. Salmon especially, but also steelhead, lamprey,

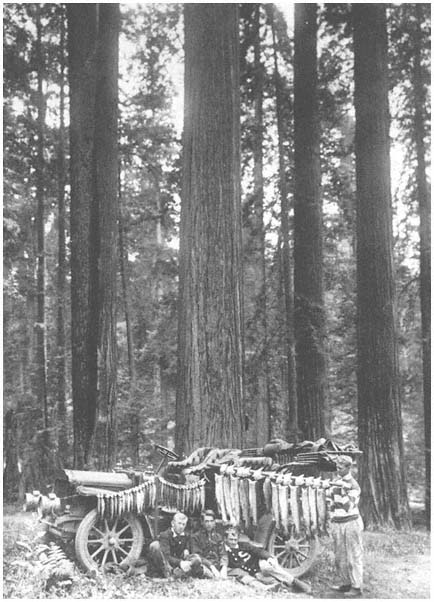

Anthropologists termed it "primitive affluence." The chinook salmon

held by this Indian woman and boy were an important element in

the coastal Indians' "food bank."

(Peter Palmquist collection)

and sturgeon, were the mainstay of Yurok subsistence. The awesome, cyclical nature of the salmon's yearly migrations over the centuries influenced almost every aspect of Yurok life. Religion, lore, law, and tribal technology all evolved from the Indians' relationship with their fishery resources.

Such dependence on salmon required conservation measures to assure that the bounty would continue. The downriver Yuroks had to let enough salmon escape to perpetuate future generations and to meet subsistence needs of upriver tribes, the Hupas and Karoks. These two needs, biological and social, for an adequate salmon escapement were met with many rituals and laws that tempered the salmon harvest.

To the aboriginal Yurok, fishing sites were (and to a great extent still are) considered privately owned. The right to fish at a particular site was transferable and governed by complex rules and laws. Rights could be loaned for a portion of the harvest. Owners of the

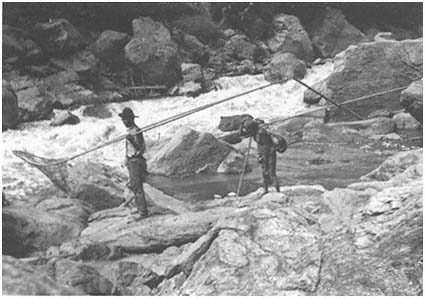

Indian property. Elderly Indian couple at a "usual and accustomed"

fishing site on the Klamath River. Such sites were held and

controlled by Indian families.

(Peter Palmquist collection)

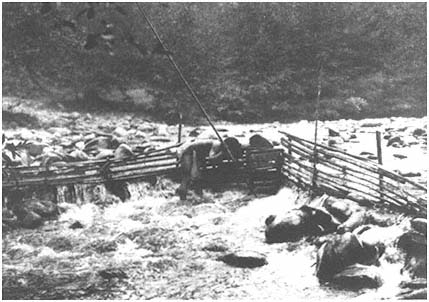

best sites were generally the "aristocrat" families of the tribes. Fishing techniques varied with the topography of the site and the type of fish being sought. Several types of nets, woven with twine made from iris leaf fibers, were used for salmon. Private ownership of restricted net fishing sites, however, could not ensure adequate subsistence for all Yuroks, so communal fish dams were temporarily built at selected sites. These weirs, constructed of log frames and a latticework of slats or poles that completely crossed the stream, blocked upstream fish migration. Sections could be opened to allow fish passage. Trapped fish were removed by dipnets and other means.

Possibly the most advanced accomplishment of California Indian cultures was the fish dam on the Klamath at Kepel. Several hundred people were involved in the annual construction of this dam. Every aspect of its construction and use was highly ritualized: it consisted of exactly ten panels, was built in ten days, and was fished for only ten days. This community project ensured that subsistence needs of all river tribes would be met, and salmon runs perpetuated.

Weirs such as this on the Klamath River were commonly used to intercept

migrating adult salmon. Yurok Indians observed complex rituals

associated with the annual construction and operation of much

larger community weirs on the lower Klamath.

(Peter Palmquist collection)

Neither net nor weir fishing could begin until the "first salmon" ceremony took place at Welkwaw, at the mouth of the Klamath River. The tribal formulist, after complex ceremonial rites, would ritually "spear" the first salmon. No person could eat salmon until this ceremony was completed.

Aboriginal Klamath fishers faced basic fishery management problems like those of today: how to cope with natural fluctuations in resources, how to control harvest while maintaining a viable economy. The Indians needed fish to survive. Clearly, as historian Arthur McEvoy has noted, Indian communities, over the centuries, learned how to "balance their harvest of fish with their environments' capacity to yield them." Salmon runs continued. Settlers of the 1850s reported that the Klamath was "alive with the finny tribe." Such was the Yurok world when the first major immigration of non-Indians arrived at the Klamath River.

Postcontact Era

Except for meeting a few explorers and fur traders, Klamath/Trinity tribes had little contact with whites before 1850. The California Gold Rush changed that dramatically. Gold seekers started settlement of the region, and reports of hostile contacts between whites and Indians were increasingly heard. Settlers demanded that Congress resolve the "Indian problem." Department of Interior Agent Redick McKee negotiated peace treaties that would preserve a small portion of tribal home territories while ceding all other lands to the state. Indians were to be taught to become farmers to lessen their dependence upon game and fish for food. Their leaders were given a choice: Be peaceful and sign the treaties, or be killed or driven out of the Country. At 4:00 P.M. , October 9, 1851, Indian leaders signed the treaties.

The new Californians did not want reservations. The most vocal called for termination or removal of Indians, although there were no lands farther west where Indians could be transferred. An editorial in the Los Angeles Star of March 13, 1852, summed up the popular attitude: "To place upon our most fertile soil the most degraded race of Aborigines" on the continent and treat them "as powerful and independent nations, is planting the seeds of future disaster and ruin." A beleaguered Congress ultimately met in secret session in 1852 and rejected all eighteen California treaties. (The injunction of secrecy was not removed until a half-century later.) This action still clouds certain legal aspects of California Indian fishing rights.

Meanwhile, as white immigration increased, Indian lands remained unprotected and confrontations, often genocidal, increased. President Franklin Pierce finally, in 1855, established the lower Klamath River Reservation and set up a military post, Fort Terwer, "to lessen friction between the new Californians and the Indians." Early superintendents of the Klamath Reservation struggled to adapt the Indian people to an agricultural life-style on the rich lands of the estuary, but the Yurok fishers resented field work. They preferred to subsist on fish and native roots, berries, and seeds. They simply wanted to be left alone, unmolested by whites.

Indians' distress with forced agricultural labor was relieved dramatically during the winter of 1861–1862, when a flood destroyed

the agency office and wiped out Indian dwellings, crops, and fields. Subsequently, the agent and staff were transferred north to Smith River. Although they were destitute, the Yuroks refused to relocate and were left to fend for themselves on the Klamath. This development, among others, led agency authorities to consider reorganizing all California Indian affairs. One result was the Four Reservations Act of 1864, which eventually established the Hoopa Valley Indian Reservation on the Trinity, upriver from the Yuroks. This putative abandonment of the Klamath Reservation was yet another glitch in the bureaucracy that in the future would prove a hindrance to the affirmation of Yurok fishing rights.

White immigration to Indian territory increased, and along with it the impact on salmon and other Indian fishery resources. Mining in headwater regions destroyed fish habitat, and miners drove Indians away from upper areas of the river. The conflict between Indian cultural fishing values and non-Indian industry had begun in earnest.

Predictably, confusion over reservation boundaries and locations led to further influx of squatters and increased pressure on government to remove the Indians and open the territory to homesteading. An army report in 1875 disclosed that the Yurok's main concern was their fish and predicted serious trouble if whites continued trespassing. Over subsequent years, squatters were ordered to leave, but the orders were largely ignored. A small military outpost was established at Requa to protect the Indians' fishing endeavors and attempt to maintain peace.

On April 1, 1876, the state of California legalized the sale of salmon caught in Del Norte, Humboldt, Shasta, and Mendocino counties. A non-Indian, Martin Van Buren Jones, soon established a commercial fishery at the mouth of the Klamath but was evicted by the army. He then moved his operation a mile tip Hunter Creek, just beyond reservation boundaries. Since Indians benefited from this endeavor, the military did not object.

Thus the lower Klamath River Indians entered a new era. White men's dollars, instead of barter, paid for their harvest of fish and allowed them to earn a living as the white world required. Commercial salmon fishing was most suitable to Indians, as this was what they could do best. In 1886, John Baumhoff, owner of a saltery also on Hunter Creek, signed an agreement with twenty-six male