Preferred Citation: Solterer, Helen. The Master and Minerva: Disputing Women in French Medieval Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1t1nb1fx/

| The Master and MinervaDisputing Women in French Medieval CultureHelen SoltererUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1995 The Regents of the University of California |

For Josef Solterer

Preferred Citation: Solterer, Helen. The Master and Minerva: Disputing Women in French Medieval Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft1t1nb1fx/

For Josef Solterer

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book has already had many lives, and the one it now enjoys in print is thanks in large part to colleagues and friends. In the beginning, during my graduate school time in Toronto, I was guided by Frank Collins and encouraged steadily by Brian Stock and Leonard Boyle. Over the years in Durham, my project took shape with the North Carolina Research Group on Medieval and Early Modern Women. I count myself lucky to have found in this group and its spirited discussions an intellectual home. Jane Burns and Judith Bennett always spurred me to think further with questions at crucial moments. Ann Marie Rasmussen and Monica Green got me to see my argument as a whole. Even at a distance, Linda Lomperis and Bonnie Krueger made me realize how my work was already part of a collective venture. Along the way, there have been many people whose reactions and suggestions have made their mark on my writing, I trust for the better. For dialogue that led me in new and unexpected directions, I am grateful to: Anne Dooley, Ann Rigney, Ronald Witt, and Charity Cannon Willard; for brainstorming sessions, to Kristen Neuschel, Paula Higgins, Danielle Régnier-Bohler, Nancy Miller, and Sarah Kay; for thought-provoking conversation, to Karen Pratt, Kevin Brownlee, and Lesley Johnson; and for proverbial wit, to Seán ÓTuama. My book took final shape as a result of four challenging readings of the manuscript from Jody Enders, David Hult, Nancy Regalado, and Gabrielle Spiegel. Engaging with them made revision a creative process and showed me again what debate is all about. In the last stages, my book has benefited greatly from the linguistic savvy of Frank Collins, David Hult, John Magee, and Brian Merrilees, and the sleuthing of my student collaborators, Louis Vavrina and Jennifer Winslow. In the end, I could not have pulled it off without Elizabeth Waters, whose staying power during record-breaking heat made the difference.

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the American Council of Learned Societies and Duke University Research Council, who funded my research throughout. The aid of many librarians here and abroad, and of the ever-ready staff at the Institut de recherche et d'histoire des textes in Paris is here gratefully recorded. Jean-Jacques Thomas and the cohort at Duke University's Department of Romance Studies sustained me with true collegial support.

My special thanks go to three fellow adventurers: Elizabeth Curran Solterer for teasing me into coming out with this book, Stephanie Sieburth for urging me to pin it down, and Michael Menzinger (+ fritz) for helping me to produce it at long last.

I dedicate this book to my father, who did not live to see it completed. His own inimitable zest for debate runs through its pages. Se non é vero é ben trovato .

TORONTO/DURHAM

JULY 1993

The Master and Minerva

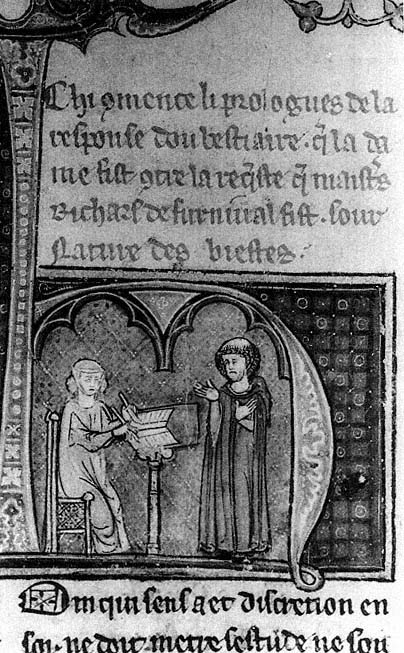

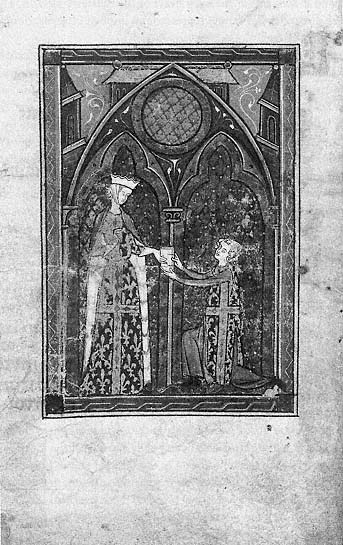

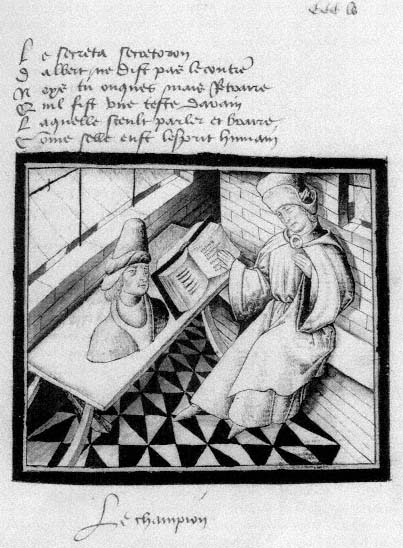

1. The respondent and the master in La Response au Bestiaire d'amour .

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 2609, fol. 32.

Courtesy of the Öster-reichische Nationalbibliothek.

INTRODUCTION

She is seated at a scriptorium desk, wielding the tools of writing (Figure 1). He stands back, his hands open-palmed as if to bear the imprint of her work. Reversing the conventional configuration found in many medieval vernacular manuscripts, this miniature depicts a woman who supplants a cleric at his customary post and assumes his function as guardian of textual culture. Further, as the rubric makes clear, this woman is busy composing her response to the master's text—"the response to the bestiary, which the lady made against the request made by master Richard de Fournival" (la response dou bestiaire que la dame fist contre la requeste que maistres richars de furnival fist). Her taking to writing gives her the chance to answer his requeste directly, in the same medium. As she writes, her eyes hold him with a challenging look: here it is a master who attends to the word of a literate woman.

This image forms the initial H for the first line of the narrative: "Hom qui sens a et discretion" (Man, who has sense and understanding). The woman's response is placed within the very letter beginning the word Hom . It is represented in a way that breaks apart the unitary, homogeneous character of mankind. In so doing, her response breaks open the discourse defining and figuring it. Her version of mankind is illustrated as a give-and-take between a particular woman and man. What would ordinarily be a subject for disputation among clerical masters such as Richard de Fournival is taken over here by a woman. At the beginning of the narrative, the confrontation between a master who disputes and a disputing woman engenders debate that, in the ensuing text, will be played out according to their two positions. Questioning the concept mankind and its constituent languages leads to a sustained interrogation of the learning of one exemplary master. Given that the opening sentence paraphrases the incipit of the

Metaphysics , this woman's response takes on a well-known treatise of the Master Philosopher, as Aristotle was called in the high Middle Ages.

I begin my study of the medieval dialectic between masterly writing and woman's response with this miniature from the Response au Bestiaire d'amour because it delineates vividly many of its key questions. First, the image poses a question concerning the figuration of women in medieval narrative. What does such figuration suggest a female figure writes in response to what she reads? That women are represented as quarrelsome interlocutors or even respondents was already an integral element of European literature by the twelfth century. Their part is inscribed in the numerous debate forms that characterize medieval lyric and narrative—the Provençal tenso , the Old French requeste, complainte , and dialogue poems, among others. Andreas Capellanus's mock dialogues in the De amore (On Love ) project female voices that reply to and often foil the suits of male lovers. The epistolary tradition pairs the work of male writers with that of women who reply warily. Even in medieval versions of Ovid's Heroïdes , the letters attributed to female correspondents mark a type of interaction. Yet what happens when a woman is portrayed reacting negatively to a text already in circulation? What happens when her response, once coded and contained within love literature, breaks out and is established separately in the circuit of texts? What are the implications of a disputing female figure whose opposition operates within literate and even learned culture?

This illumination from the late-thirteenth-century Response au Bestiaire d'amour also raises the issue of how such figures of master and disputing woman register socially. It prompts us to consider the connection between figurative languages and conventions of reading and writing prevailing in medieval Europe. Such a connection needs to be gauged extremely carefully. We can neither reduce the figure to a symptom or effect of those conventions nor regard them critically as distinct phenomena. In this manner, the figure of the woman respondent occasions an inquiry into the practices of vernacular literate culture.

To embark on such an inquiry is to face straightaway a heritage of vying claims regarding the relation between medieval laywomen and the domain of written texts. The first investigations sought to establish such a relation empirically. In the early nineteenth century, critics set out to prove that medieval women were indeed literate. The French historian Jules Michelet exemplified this approach. His essay, "Fragments d'un mémoire sur l'éducation des femmes" (1838) established the standard for tracing the development of women's skills. "They [women] were deemed worthy of reading and writing . . . they became learned as well as pious."

Michelet's claim launched the argument for laywomen's entry into the world of letters.[1] In most subsequent efforts to survey the European Middle Ages, critics collected cases such as the Bestiaire respondent as evidence for women's participation in literate culture.[2] Whether those examples involved known individuals or textual personae, they were used to substantiate the argument for women's involvement with written texts. Such a quantitative way of proceeding laid the groundwork for the view that laywomen presided over the two principal poles of vernacular literary production—as patron and privileged reader. One of the first theorists of literacy, Herbert Grundmann, articulated this view best when he asserted: "By women and through them, vernacular poetry achieved a literate form and became 'literature.'"[3] Grundmann's formula typifies the habit of interpreting the numbers of medieval women linked with bookish culture as proof of their decisive activity.[4]

But because such literate women appeared prominently in a world mediated by a figurative language, their prominence has merited closer scrutiny. The presence of women readers in vernacular literature raises the question of their function. As Georges Duby has observed, the instance of women playing an authoritative role of patron and reader suggests a complex mechanism whereby their bookish superiority works to the advantage of their overlords.[5] Far from demonstrating women's influence over vernacular writing, it points to their likely function as go-betweens in a game of clerical control. The figures of "masterful" women readers show the signs of a certain autonomy: they exercise the skills of reading and writing associated with the clergy. Yet, at the same time, these figures bespeak the designs of a small, literate caste that presents women in this light so as to better discipline them. The long-standing link between women and the literary sphere is too fraught to allow for a one-to-one correspondence between textual figure and social role. Under the iconoclastic pressure of feminist analyses, the convention of the female reader has been effectively dismantled so as to reveal the fact that such images need not necessarily confirm laywomen's influential participation in literate culture.[6]

For all their differences, what these two interpretative positions share, paradoxically, is a very limited conception of women's relation to the domain of written texts. Women are restricted to first-degree literacy. While they are attributed the elementary skills of reading and writing, rarely, if ever, are they deemed to use them practically. Their involvement in letters is passive. Moreover, medieval laywomen in these accounts are missing the "literate" mentality by which one interprets and adjudicates the world textually. Such an understanding is discernible across much high-medieval

vernacular literature. Women are commonly typed as literalists—unable to pass beyond the letter of a text. From the scores of inscribed female readers in romance to Dante's Francesca, they are presented as reading poorly, prone to misunderstanding.[7] And their poor reading record has everything to do with their inability to gain access to the symbolic: "The woman says: these things are too obscure for me, and your words are too allegorical; you will have to explain what you mean" (Muller ait: hi mihi sunt nimis sermones obscuri nimisque verba reposita, nisi ipsa tua faciat interpretatio manifesta; De amore , book I).[8] Like one of Andreas Capellanus's personae in the De amore , women are represented as confused by any level of signification other than the literal. They appear beholden to their masterly interlocutors to make the symbolic comprehensible. Yet even with such instruction, it is unclear whether they are ever fully initiated into the symbolic mode (verba reposita).

By contrast, the cleric is singled out by his subtle and sophisticated figurative understanding.[9] Trained to extract the kernel of meaning from its various husks—as the exegetical trope describes the process—the clerk excels in working his texts symbolically. The figura is his characteristic property.[10] It is, of course, the master—the head of clerkly culture—who champions the symbolic register.[11] Like the cleric in the Response au Bestiaire miniature, the magister is meant to brandish the figura , and with it all the tools of text-based learning.

This typing of the woman vis-à-vis the master brings us to the basis of a literate mentality. As Brian Stock has argued, the difference between literal and symbolic makes sense only within the framework of literate culture. He writes: "Such a distinction [figure/truth, symbolic/literal], of course, was unthinkable without a resort to the intellectual structures of allegory, which were in turn a byproduct of the literate sensibility. For, to find an inner meaning, one first had to understand the notion of a text ad litteram ."[12] In this sense, the idea of women's participation in the work of high-medieval literate culture looks compromised. Insofar as they are usually depicted laboring over a literal sense, they are not judged to be literate in the fullest possible measure. Women's second-degree literacy appears untenable. So too their capacity to operate within a world defined by texts. The masterful act of symbolic interpretation seems out of reach, with the result that women's engagement with such interpretation through writing looks an even more remote affair.

Is the Bestiaire respondent then just another in the long line of literalists represented by medieval narrative? When she takes stylus in hand to write against the master's requeste , does she concentrate only upon its literal sense? Early on in her text, she observes: "For truly I know that there

is no beast who should be feared like a gentle word that comes deceiving. And I think it well that one can be a little on guard against it" (Car je sai vraiement qu'il n'est beste qui tant fache a douter comme douche parole qui vient en dechevant. Et si cuic[h] bien que contre li se puet on peu warder).[13] This respondent recognizes the power of the symbolic and begins to pick the master's bestiary metaphors apart adroitly. She analyzes the symbolic language they comprise as a form of damage to women. Yet in so doing, she is represented as capable of deploying the symbolic herself. In fact, her reading exploits the figura as fully as would any master's lesson. In the Response , it is no longer a question of whether a woman can interpret symbolically or not, but rather what her interpretation enables her to do.

I shall argue that the encounter between the master and the woman respondent changes the medieval type of the female literalist in significant ways. There we can discern how women respondents emerge as decoders of the symbols of masterly writing. More importantly, in such an encounter we can find them becoming critics of that writing. If the case of the Bestiaire d'amour respondent gives us any clue, women are seen to interpret negatively the symbolic language associated with the masters. Far from remaining at a superficial level, stumped by the letter of a text, the respondent comes to exercise her own skills in symbolic interpretation. With these skills, she is equipped to contest the sexualized representations of women—the various feminine metaphors of flora and fauna—that hold sway, and to challenge the very symbol system that defines the clerico-courtly discourse authoritatively.[14] Indeed, the respondent disputes what I call, after Pierre Bourdieu, the symbolic domination of a tradition of representing women in medieval letters.[15]

Once we begin to entertain such an argument, we should consider any medieval models of a woman's response. There are, in fact, many, though they have rarely been conceptualized as such.[16] The first, pervasive model is a rhetorical one. A variety of medieval topoi existed that associated woman's language with the format of response. Dante evokes them suggestively in the De vulgari eloquentia where he surmises: "But although in the Scriptures woman is found to have spoken first, it is nevertheless reasonable for us to believe that man spoke first. For it is incongruous to think that such an extraordinary act for humankind could have first flowed forth from a woman rather than from a man . . . man spoke first by way of response" (Sed quanquam mulier in scriptis prius inveniatur locuta, rationabile tamen est ut hominem prius locutum fuisse credamus: et inconvenienter putatur, tam egregium humani generis actum, vel prius quam a viro, a foemina profluisse . . . per viam responsionis primum fuisse locutum

(book I, iv).[17] According to the standard topoi taken from the Bible, the first human speech act in Eden is attributed to Eve. Yet even when this is denied and reassigned to Adam, Eve's speech remains situated in the framework of response. If she did utter the originary word, she did so in reply to the Lord. If she did not, she is still described implicitly as responding to her human lord. This account of the first Edenic dialogue reiterates the scholastic belief in the secondary status of human language. And in its puzzlement over Eve, it accentuates the peculiar secondariness of her speech. Starting in paradise, women are allotted the role of respondent.[18]

In the high-medieval didactic work known as the Miroir des bonnes femmes we can see how the rhetoric of the woman's response is further reinforced.[19] Commenting upon the Biblical scenario in Eden, the Miroir focuses on Eve's response not to God or Adam but to the snake. The rubric reads: "The second stupidity of Eve was that she responded too frivolously" (la seconde sotie de eue fu en ce quele respondi trop liegierement). In this manual on noblewomen's comportment, Eve's responsiveness is introduced as a negative exemplum. It is a preeminent illustration of how not to behave. The passage continues: "I want you to know the story of the wise lady who responded to the mad knight and who spoke of [his] folly. She did not reply without her lord, but she would talk openly with him [her lord] about it. If she took the knight for mad, he took her for wise."[20] In this comparison between Eve and la sage dame , the first woman is one with a loose tongue who does not recognize the dangers of her responsiveness. The wise lady, however, refrains from the linguistic errors of her progenetrix. In an obvious courtly setting, the lady reacts circumspectly to the problem of answering men. She is seen to recognize the dangers of their "mad" language. With this exemplum, the Miroir promotes a lesson of a wary response. The wise lady rebuffs the advances of unreliable suitors who speak to her and follows instead the verbal lead of her lord. Whoever that lord might be, she is positioned to speak after , to take up his first utterance. The wise woman's response is defined by the moral "Don't speak until spoken to."

These two cases from the late Middle Ages testify to the rhetoric of women's propensity for response. There are many others. Found in fictional and didactic works alike, the topos of the woman respondent establishes the link between woman's language and the posture of replying to man's. This link could be constructed negatively or positively. As we have seen, once responsiveness is labeled a fault, a woman's response per se is colored pejoratively. And yet absolute silence being impossible, the form and substance of a woman's response were also addressed. In this sense

the topos could be inflected positively, in keeping with the classical Latin etymology of the verb respondere —to reciprocate, to promise or pledge in return. As long as a woman's response conformed to the dictates of a man's verbal act, it could function usefully in the network of human communication.

These rhetorical characterizations undergird the second, generic model of woman's response. Again, the etymology of the word makes the point clearly: response is a Provençal, Old French neologism—a characteristically medieval form. Already apparent in the range of Provençal genres in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, it involves dialogue and debate poems that evolve between a female and a male speaker.[21] Of the various poetic genres that fit this definition, the most noteworthy is the tenso , one that, significantly enough, is well represented in the repertory of the trobaritz , the women troubadours.[22] According to Peter Dronke, all these "response" forms share "the spontaneous movement of poetic answering."[23] Without delving into the stereotypes that lead Dronke to associate spontaneity with putative female genres—something we have already found to be amply borne out rhetorically (compare spontaneous/legere )—I want to point out the key element of "answering." The Provençal tenso develops as a series of responses to a statement of love. The genre depicts adversarial male and female personae who dispute various aspects of love. Invariably the woman is in a position of resisting the man's onslaught. The tenso between Guillelma de Rosers and Lanfranc Cigala exemplifies this dynamic:

Domna, poder ai eu et ardimen

Non contra vos, qe.us vences en iazen,

Per q'eu fui fols car ab vos pris conten,

Mas vencut vueilh qe m'aiatz con qe sia.

Lafranc, aitan vos autrei e.us consen

Qe tam mi sen de cot e d'ardimen

C'ab aital geing con domna si defen

Mi defendri'al plus ardit qe sia.

(lines 49–56)[24]

Lady, I have the strength and the daring not to oppose you since I could vanquish you lying down, for which reason I was crazy to have started disputing with you, but because I desire that you should vanquish me in whatever way possible. Lafranc, I grant and assure you that I feel such daring of heart that with the savvy with which a woman defends herself, I shall defend myself in the most brazen way possible.

These two final stanzas of the tenso reveal the twofold challenge of a woman's response. Guillelma is reckoning with the various maneuvers that typify Lanfranc's language—here, the characteristic claim that the man will prevail by being overcome by the woman. This paradoxical contention is coded in terms of men's force (poder) versus women's savvy (geing). Yet the woman interlocutor is confronting the designs of amorous discourse the personae articulate. The defense she must mount is also directed against the very tradition of speaking about love to women. Guillelma and Lanfranc's tenso dramatizes the formidable power of a prevailing symbolic language.

In the Old French repertory of requeste/response , the problem of contesting that symbolic power also comes to the fore. Take, for instance, an early-fourteenth-century case entitled La Prière d'un clerc et la response d'une dame .[25] The woman contends:

Dites quanque voudrez, je vous escouterai,

Mes ja, certes, pour cen plus tost n'ous amerai.

Ja pour toutes vos truffles plus fole ne serai.

Ausi com la cygoigne ne plus ne mainz ferai.

La cygoigne mengüe le venim et l'ordure

Ja ne li mesfera, quer c'est de sa nature.

Mes non fera a moi, j'en sui toute seüre,

Trestout vostre parler, quant je n'i met ma cure.

(lines 181–88)

Say whatever you want to, I'll listen to you. But I will not love you, that is more than certain. For all your foolishnesses, I will not be so mad. Just like the stork, I'll do no more, no less. The stork ingests venom and dung so that they will not hurt it, for that is its nature. But so long as I take care, your talk will not do it [harm] to me, I'm sure of it.

Her response focuses on the question of the clerk's dangerous language. The trope of truffles (foolishnesses) captures the flavor of a language that is outlandish and at the same time disturbing. Further, it carries with it a foul intent (venim/ordure). The respondent thus deploys her own symbol of the stork not only to keep her distance but to expose the potential harm of the clerk's word. Implicitly she elaborates a critique. From within the conventions of amorous discourse, this woman's response signals a challenge to that discourse. However discreetly, the response raises the issue of the discourse's possible destructive effects.

There are also signs of such a challenge in the epistolary genres of Old French known as saluts d'amour . In the unusual instance of a late-

thirteenth-century love letter attributed to a woman (salus d'amours féminin ), the respondent takes her clerkly interlocutor to task linguistically:[26]

Biaus amis, qui si me proiez,

je ne cuit pas que vous soiez

si destroiz por moi com vous dites,

car trop de losenges petites

savez pot la gent decevoir.

Honis soit qui a dame dira

qu'il l'aint, s'il ne dit voir .

(lines 1–7)

Dear friend who beseeches me, I don't think that you can be quite so distressed about me as you say, for you know too many of the little slanderous expressions [losenges] to deceive people. "He who does not tell the truth when he says he loves a woman shall be shamed ."

The problem, once again, resides in the disturbing and fraudulent character of the clerk's language. "Losenges" is no external threat here. It does not refer to the paradigmatic slander of those outsiders called lauzengiers or mesdisants who play a stock role in medieval love poetry. Instead "losenges" is internalized. It comprises a danger intrinsic to the prevailing discourse invoked by a lover to address his lady. The notion of verbal destructiveness thus applies to its conventional figures. It is the woman respondent who begins to say as much.

Such a concept of verbal destructiveness was taken over by many medieval clerical writers to justify the model of the modest woman who speaks circumspectly. Witness the late-twelfth-century didactic text, Le Chastoiement des dames of Robert de Blois.[27] In a commentary on woman's social manners, Blois is concerned with instructing women how to decline requestes or offers of love. His concern has everything to do with the likely harmful quality of those offers. In Blois's account, declining means knowing how to avoid this harm by responding to the would-be lover in an unambiguously negative way. To this end, he sees fit to include a trial response for his women readers:

Quant vos sa plainte oï avrez,

Tot ensi se li respondez:

"Beaux sire, certes a mon vuil

N'avroiz vos jai de par moi duil,

Et se vos pot moi vos dolez,

Saichiez bien que fol cuer avez. . . .

Ne sai qu'en moi veü avez,

Mes bien pert que vos me tenez

A la plus nice, a la plus fole,

Quant dite m'avez tel parole.

De tel beaulté ne suis je mie,

Qu'ale face panser folie.

Et certes se je tele estoie,

Plus natemant me garderoie . . . .

Ne le dites pas en riant,

Mes ausi con par mautalant.

(lines 684–89, 714–21, 738–39)

When you have heard his complaint, respond in the following manner. "Dear sir, it is certainly not my wish that you have any sorrows, and if you are grieving on my account, you should know that you have a mad heart. . . . I don't know what you saw in me, but you are lost if you take me for the most gullible and naive when you speak to me with that language. I am hardly that beautiful; it would be madness to think so. And were I like that, I would be careful to be on guard. . . . "Don't tell him [the knight] this laughingly, but with a certain irritation.

Blois elaborates an unyielding "woman's response"; it exposes the fallacies of the knight's beguiling pretty talk, just as it queries its ulterior motives. Moreover, it is meant to be delivered sharply and judgmentaly.

As the final recommendation in a comprehensive scheme to discipline women's conduct, Blois's set piece gives us some sense of the net of maneuver and manipulation in which a woman's response is caught. That Blois ordains what the response should say and how it should be spoken is symptomatic of the habit in high-medieval culture to prescribe women's voices. It is his prerogative as cleric to establish how the woman responds. Further, it points to the larger social value of training laywomen to be wary as far as men's advances are concerned. This is part of the clerical learning about women that I shall explore in part 1. Yet precisely this interest of Blois's in mandating a woman's response gives us a glimpse of the response's considerable strategic potential. His insistence on devising his own version bespeaks a concern for all that women could say in response to the dominant courtly and clerical discourse on them. Whereas Blois's response lets that discourse stand unscathed, there is always the possibility for others to take on that discourse critically.

Here we circle back to our argument regarding the woman's response. Throughout the high Middle Ages, the response increasingly became a field for challenging the dominant feminine symbols in poetic discourse. Rhetorically and generically, it provided a framework in which a critique of the standard figures could develop. And in this it corresponded strikingly

with the scholastic ritual of the disputation. While the woman's response displayed a contestatory aspect typical of so much of medieval literature, it derived its particular force from the disputatio .[28] Moreover, it resembled the set role of the responsio (response) in these debates as they were conducted in the schools and the universities. This is the role of the student set the task of replying to the masters and disputing their propositions point for point. The Bestiaire d'amour respondent epitomizes such a student; in fact, the intense oppositional engagement of her response mimics the public sparring matches of the disputation that defined intellectual life in the high Middle Ages. This disputationa] character of the woman's response was further reinforced by a variety of social factors: the numbers of noble and bourgeois literate women during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were steady, the rudiments of education were placed in their hands, and opportunities for book learning were even available to them.[29] Socially, there were reasons supporting women's figurative affiliation with scholastic practices such as the disputatio . By the late Middle Ages, at the time of those heated debates known as the Querelle des femmes , the figure of the woman respondent/disputant no longer conformed to the many powerful courtly and clerical prototypes in the line of Blois.

But how could a woman's response intervene efficaciously in the domain of textual culture? Even when we account for the prestigious model of the disputatio informing it, the question of its specific challenge still remains. Faced with a discourse on women legitimated by clerkly scholarship, how precisely could the response dispute it? The cardinal criterion available to the woman's response, I shall argue, is the idea of injurious language: words in and of themselves can cause harm to the public. Such an idea proves especially elusive to us today. In a society where our sense of the power of language is so thoroughly attenuated by other media, where violence is linked more and more with audiovisual imagery, the possibility that words can enact harm is difficult to fathom. Were it not for the reemerging concern over hate speech and the idioms of "fighting words," the idea of verbal injury would seem remote, little more than a curious avatar of an earlier mentality.[30] Yet for much of medieval culture, injurious language was an article of faith. "Sometimes words cause more trouble than flogging" (aliquando plus turbant verba quam verbera). Gregory the Great's dictum, cited proverbially throughout the Middle Ages, exemplifies this sense of the damaging power of language. The echo "verba/verbera" gets at the heart of the analogy between words and physical blows. In a preprint society such as the medieval world, this link was acutely felt, and with it the fundamental connection between words and action. Simply put, words constituted action. Neither a substitute nor an

alternative for action, they functioned as action. They were thus also actionable.

The signs for this medieval understanding of injurious language are legion. Inheriting the classical rhetorical conceptions of the languages of praise and blame, many thinkers from the twelfth century on were preoccupied with the good that words could incur and the harm that they could inflict.[31] Among the many treatises on the language arts, there were those that dealt specifically with disciplining the tongue. Take, for example, Albertano of Brescia's Liber de doctrina loquendi et tacendi (Book on the Doctrine of Speaking and Being Silent ) and Hugh of Saint Cher's De custodia linguae (Concerning the Care of Language ).[32] And there were those that focused on the problem of wayward language, such as Robert Grosseteste's De detractione et eius malis (On Detraction and its Evil ).[33] Given this preoccupation, it is hardly surprising that catalogues of verbal transgression were drawn up. In the high Middle Ages, we can point to a significant number of clerical pastoral manuals that identified every possible transgressive speech act. Slander, perjury, rumor mongering, sarcasm, lying, invective, calumny, false praise: all these types were laid out and assessed according to motivation, defining features, and appropriate compensation.[34] In these analyses, the rhetorical categories of injurious language are approached practically. As a result, their occurrence in everyday speech and writing can be judged. Acts of verbal injury are subject to correction. Whether these particular pastoral manuals were ever used to condemn individuals and mete out punishment is a moot point. But what is clear is the governing mentality among the medieval clergy and society at large that evaluated any number of speech acts as punishable.[35] Indeed, such acts were criminalized. This is borne out amply by the inquisitional record of public beatings and mutilation of those convicted of various verbal sins. The person who spoke injuriously against ecclesiastical or political authority was to suffer the consequences physically: that person's words were turned back against the body itself.[36]

What was already a profound understanding of injurious language gained further technical weight during the later Middle Ages. This was due in no small part to the revival of Roman law.[37] The canonists' extensive commentary on Justinian's Code and other inherited precepts brought to the fore the Roman conception of iniuria as the code defined it.[38] "You can bring an action for injury in the usual way against those who are ascertained to have done anything for the purpose of reflecting upon your character" (quin immo adversus eos, quos minuendae opinionis tuae causa aliquid confecisse comperietur, more solito iniuriarum iudicio experiri potes).[39] This statute established a tort whereby any offense directed against an individual's or a group's reputation was subject to legal judgment. According to medieval canonists, it stigmatized any words intended

to hurt a person's or group's public name.[40] The code's statute and its medieval interpretations thus served to reinforce the rhetorical and pastoral principle of injurious language. Over the course of the fourteenth century, this principle grew more and more prominent precisely because it was associated with the formidable apparatus of classical legal thought.[41] In this manner, it became a question of political discussion as much as a clerical, ecclesiastical concern. By the fifteenth century, the problem of verbal injury was focused in the public domain.[42]

I sketch this background so that we can recognize the context for the idea of verbal injury in the woman's response. Its use was by no means unique. In fact, it was symptomatic of the pervasive concern over verba/verbera animating high-medieval society. But it was nevertheless highly unusual for the woman's response to employ the concept of verbal injury as a powerful tool against the dominant symbolic discourse on women. Ordinarily, we are accustomed to attribute such a concept to the powers that be. It is the prerogative of the prevailing authorities, who invoke it as a way of securing the existing order. In periods of social unrest such as the later Middle Ages, the Church used it to brand the delinquent believer, or royalty employed it to single out the seditious language of citizens it suspected. With the charge of verbal injury, the heretic and the traitor were stigmatized, accused of the worst verbal infraction—blasphemy.[43] Yet in the case of the medieval woman's response, this charge was taken right to the center of a reigning poetic discourse. The criterion of injurious language was a spearhead directed against the most orthodox symbolic language about women, and thus against the most indisputable.[44] It was the driving principle of a developing critique of the prevailing feminine representation that passed for learning in vernacular medieval culture.

No work better stood for this learning than the Roman de la rose . Yet significantly, no French work more powerfully elicited the problem of verbal injury. Contained within Guillaume de Lorris's and Jean de Meun's text are both a stock of misogynous wisdom concerning women and an analysis of slander—all this in a narrative that closely resembles a university debate between masters and disciples. As many have remarked, the Rose is a disputatio gathering together various authorities who speak vehemently and often slanderously on the subject of loving women.[45] It is the female allegorical figure, Reason, who addresses explicitly the danger of such slanderous or injurious language:

Tencier est venjance mauvese;

et si doiz savoir que mesdire

est encore venjance pire.

Mout autrement m'en vengeraie,

se venjance avoir en volaie;

car se tu meffez ou mesdiz,

ou par mes fez ou par mes diz

secreement t'en puis reprendre

por toi chastier et aprendre,

sans blasme et sanz diffamement . . . .

Je ne veill pas aus genz tancier,

ne par mon dit desavancier

ne diffamer nule persone,

quele qu'ele soit, mauvese ou bone.

(lines 6976–85, 6993–96)[46]

Quarreling is evil vengeance, and you should know that slander is even worse. If I wanted vengeance, I would avenge myself in quite another way. For if you misbehaved or spoke slanderously, I would secretly find a way through my actions and my words to chastise and instruct you without blame and without defaming you. . . . I do not wish to quarrel with people or to repel or defame anyone by my word, whomever he might be, good or bad.

Reason distinguishes her own teaching by the absence of any defamatory elements. It is, quite simply, blameless. Yet in making this distinction, Reason draws attention to the potential link between authoritative languages and slander. She suggests the possibility that those languages promoted as doctrine can prove injurious. Such a possibility inheres in the speeches of many of the allegorical personages in Jean de Meun's Rose . We have only to think of Genius, Ami, or Male Bouche , the emblematic bad-mouther. But in its largest terms, that possibility of slander implicates the narrative as a whole. The profound irony is that the text constituting the most encyclopedic medieval knowledge of women, as well as the most elaborate symbolic language representing them, raises the issue of its own injurious character.

This problematic of verbal injury was pursued specifically in relation to poetic texts by the fourteenth-century writer Guillaume de Machaut. His Jugement dou Roy de Navarre rehearses a dispute between a lady and Guillaume over the slander of women in his love poetry:

Guillaume. . . .

Se je le say, vous le savez,

Car le fait devers vous avez

En l'un de vos livres escript,

Bien devisié et bien descript:

Si resgardez dedens vos livres.

Bien say que vous n'estes pas ivres,

Quant vos fais amoureus ditez.

(lines 862, 865–71)[47]

Guillaume. . . . If I know it, you know it, for the matter involving you is what you have written in one of your books and well described and depicted. So look in your books. I really know that you aren't drunk when you compose love poetry.

Here the charge of "mesdisance" (line 831) is levied against the writing of an individual poet. This disputant takes exception to one of his books, and by extension to all of his work. She is unwilling to accept the usual excuse of unruly behavior (ivresse ) that is part and parcel of the lover-poet's identity in medieval amorous discourse. Of course we must not lose sight of the fact that her charge of verbal injury comes out of Machaut's own text. Like the Rose , the Jugement dramatizes the problematic. Indeed it goes so far as to represent Guillaume's desire for correction (line 911). Yet by dint of explicitly presenting the problem, the Jugement attempts to deflect it. Depicting the poet's own judgment and punishment is one way of defending him against the claim that his work is slanderous.

With the early-fifteenth-century Querelle des femmes , the problem of verbal injury gained particular momentum.[48] In this framework, it moved out of the context of poetic works and into that of public polemic. The first authoritative text targeted was, not surprisingly, the Roman de la rose . It was the professional writer Christine de Pizan who launched the charge of slander in an open debate with several Parisian humanists defending Maître Jean de Meun. This woman's charge exploited the issue of verbal injury in several innovative ways. To begin with, Christine's dispute with the Rose introduced a particular technical conception of defamation.[49] In her first letter addressed to Jean de Meun's humanist defenders, she asks:

En quel maniere puet estre vallable eta bonne fin ce que rant et si excessivement, impettueusement et tres nonveritablement il accuse, blasme et diffame femmes de pluseurs tres grans vices et leurs meurs tesmoingne estre plains de toute perversité?[50]

In what manner could it [the Rose ] be valuable and directed toward a good end, that which accuses and blames women so excessively, impetuously and so untruthfully, which defames them by several enormous vices and finds their behavior full of all manner of perversity?

Christine's question draws attention to the effects of defamatory language. And it refines the general idea of words that do harm by reintroducing the classical notion that words can damage the fame (fama ) of a person or group.[51] On a larger scale, Christine's critique of the Rose made visible the public reputation of women and its peculiar vulnerability to defamation.

Consequently, it planted the problem of texts defaming women squarely in the public domain. Her part in the Querelle du Roman de la rose made it an issue for the community as a whole. As Christine asserted in the same letter: "A work of no utility and out of the common good . . . is not praiseworthy" (oevre sans utilité et hors bien commun ou propre . . . ne fait a louer; Hicks, 21).

In this notion of "the common good" we can detect the second, farreaching innovation of Christine's disputation. Putting the emphasis on the public implications of defamation enabled her to transform the Querelle de la Rose ethically. Ultimately Christine is concerned with the damaging effects a defamatory text can produce upon the public. What injures a particular social group injures that society at large—the body politic. Christine engaged with the Rose powerfully by gauging the social benefits or liabilities of this text and by holding it publicly responsible. Following her lead, we will examine this question of the value or end of medieval works representing women; our inquiry will bring us to consider their defamatory language from an ethical point of view.

However singular Christine's disputation may appear, its ethical point was by no means lost. Another debate in the fifteenth-century Querelle des femmes pushed it still further. With the controversy over the poem La Belle Dame sans merci by the well-known court poet Alain Chartier, the problem of the value of a work became a matter of public adjudication. In a response to Chartier's poem attributed to three women, "Jeanne, Katherine, and Marie," the notion of defamation against women was exploited in a fully legal sense. Such a juridical conception was already apparent in the Querelle de la Rose : when Christine lodges her complaint against Jean de Meun's text in the public forum, she speaks legalistically. Indeed there are many cases, such as Guillaume de Machaut's Jugement poems, where a legalistic force is brought to bear on literary language. The pattern reaches all the way back to the Roman de la rose and the teachings of Reason cited above, where she alludes to the right to plead the case of defamation before a judge (par pleindre, quant tens en seroit, au juige, qui droit m'en feroit; lines 6989–90).

What distinguishes the women's dispute with Chartier's Belle Dame is the move to charge an authoritative poetic text with a crime of defamation. Jeanne, Katherine, and Marie indict the poet for his "writings in which you defame us so greatly that we became infamous" (res escrips, esquelz tu nous diffames Tant grandement que se fuissons infames; lines 12–13).[52] The women make the link between his defamatory writing and their infamy—their complete loss of fame or reputation legally speaking. Because the masterful writing of Chartier causes their name to become infamous, they seek amends. This fifteenth-century woman's response

worked to make the language of an authoritative poem not only ethically responsible but legally actionable as well.

This move comes from figures not easily associated with the privilege of legal redress. In this late-medieval scene, the case of women disputants "suing" an established and well-regarded poet is eye-catching. Once again the roles are reversed, and women representing the public domain with the power of the law behind them dispute the defamatory language of a prominent poetic text: they take on a work of a master poet by recourse to the magistrate.

"In the search to injure another verbally, is there not, in effect, the idea of preventing the other from responding, of shutting the person up; is there not also this idea of combat in words—of jousting, so to speak—where the one who shuts up loses, and the art of responding is considered a type of self-mastery?"[53] Evelyne Larguèche's description echoes hauntingly with the problem and the promise of the medieval woman's response. The woman's response is bound by the dominant discourse on woman that promotes the model of the modest and wary woman. It is caught somewhere between discreet talk and silence, between reacting politely and, in Larguèche's terms, being shut up. Given the possibilities that such a discourse is injurious, such silence seems all the more likely. Yet the medieval woman's response allows for a challenge. More importantly it forges that challenge in the well-known but seemingly inapplicable terms of injurious language. Entering the combat of words that is the disputation, the woman's response reverses the usual dynamic of injurious language by naming it outright. As a result, the concept of verbal injury can be directed at the heart of the discourse on women relayed by clerical magistri and master vernacular poets. This concept can be attributed to the very powers that promulgate the notion and reserve it for stigmatizing outsiders. In the pages that follow, I shall track the various rhetorical, ethical, and legal ways the woman's response foregrounded the problem of the social controls of discourse. Tracing the response in late-medieval French culture will clarify what I take to be an important chapter in the history of the conception of verbal injury. Within the framework of the response, the conception is progressively shaped—from the general notion of insulting language to the technical understanding of defamation. The woman's disputational response attests to major developments in the view that language found to be damaging can be taken to public account. The polemical debates of late-medieval France offer a particularly rich site for establishing such language as actionable.

In order to study the dialectic between masterful writing and women's response, I have made this book a diptych, with one part for each position.

These positions are by no means fixed. I do not intend to reinforce two binary opposites pitting master against woman respondent. I derive these positions from the medieval disputation and use them pragmatically. My pragmatic choice is especially crucial when it comes to the position of the woman's response. By attributing a role from the disputation to female figures, I do not assign to them any particular definition of femininity. Nor do I assume them to be women. In this study, the medieval figure of a woman disputant is a role that can be played by anyone. This is already evident in the disputation, since its performative quality allows participants to take on a number of different roles. The disputational figure of a woman could be deployed by women or men. The Bestiaire d'amour respondent illustrates how difficult it is to know which is the case. But we do know that this figure was adopted by individual women, as the case of Christine de Pizan demonstrates clearly. I shall examine all these cases together because, in the end, it is not the gender of those who use the figure of the woman respondent that concerns me. Rather it is the functions and effects of the figure. What are the implications of this figure emerging in late medieval literate culture?

Pursuing such a question involves an enormous field of inquiry. This is particularly true because of the disputational character of so much of medieval literature. I have selected texts that explicitly stage the encounter between the figures of master and woman respondent. And I begin by studying the medieval institution of mastery so as to establish the context and the terms of the woman respondent's interventions. Part 1 traces the ritual practices of the clerical world of learning as they appear in highmedieval French narrative. Like their scholastic brethren, the vernacular figures of the master and disciple test their knowledge of women in the disputation. This testing process creates and reinforces a language about women that proves domineering. I will look first at the various ways the disputation over women functions as a binding agent between disciples, that trains them for the role of magister . But I will focus principally on a symbolic domination of women resulting from the language shared by master and disciple. Two models of mastery, the Ovidian and Aristotelian, will serve as test cases. Looking at a variety of debate poems that use these models will enable us to clarify how such a domination operates. In thirteenth-century and fourteenth-century narrative, however, there are signs that the intellectual mastery of women is no sure thing, and correspondingly, that the symbolic dominance it exerts does not hold. In chapters 2 and 3 of part 1, I shall trace the uneven legacy of this symbolic domination.

Part 2 investigates how the woman respondent came to dispute a dominant masterly discourse on women. By shifting from the figures of

masters disputing the subject of women to the figures of women disputing, I sharpen the issue of a discourse's accountability to its audiences. In what ways did the woman's response press the problem of the social regulation of representation? There were already glimmerings of this problem within thirteenth-century and fourteenth-century narrative; the Bestiaire d'amour and the Response au Bestiaire illustrate this amply. Yet in the later Middle Ages the problem intensified. Not only did the woman's response indict existing texts, but in the case of Jean LeFèvre's Livre de leesce and the debate over the Roman de la rose it arraigned the canonical works of earlier generations. The woman's response reached back in textual time, extending its challenge of verbal damage to the literary tradition per se. In studying the later phenomenon of the Querelle , I wish, then, to draw connections between the critique of feminine representation internal to the masterly discourse and the critique coming from without, between a lover's "wounding, beautiful talk," as one respondent puts it, and the injurious character of the discourse as a whole.

1—

PROFILES IN MASTERY

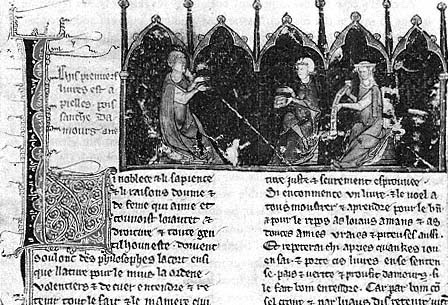

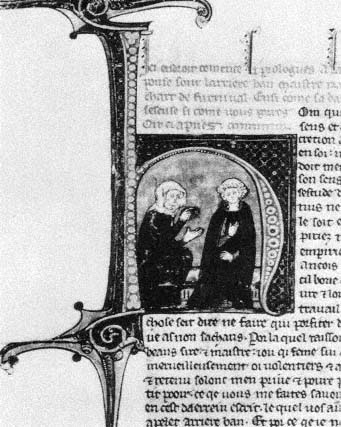

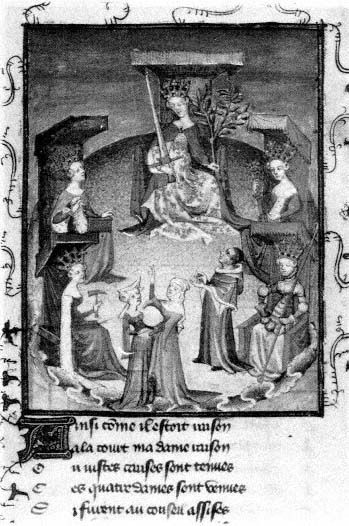

2. The Master Philosopher meets a woman. Marginalia in a fourteenth-century

Roman d'Alexandre .

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, f.fr. 95, fol. 254.

Photograph, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

3. Aristotle upended. Marginalia in a fourteenth-century Roman d'Alexandre .

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, f.fr. 95, fol. 61 verso.

Photograph, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

1—

Ovidian and Aristotelian Figures

There are three things which Aristotle failed to explain: the toil of bees, the ebb and flow of the tides, and the mind of women.

Irish proverb

With the thirteenth-century Lai d'Aristote , the medieval clergy offers us a parable of its relations with women. This is a "boy meets girl" tale involving no less than the Master Philosopher. He is depicted as a distracted intellectual, taken from his books, and she as a seductress who magnifies her alluring figure with a mirror (Figure 2). This encounter goes directly against Aristotle's recommendation to the emperor Alexander to keep away from women:

Si vos porra on mener paistre

Ausi com une best en pré!

Trop avez le sense destempré,

Quant por une pucele estrange

Voz cuers si malement se change.

(lines 166–70)[1]

One could thus put you out to pasture just like a beast in the field. When your heart changes so completely on account of a strange girl, you have destroyed your good sense.

The master fares no better than his "woman-crazy" student, for in the subsequent scenes of seduction, Aristotle is so attracted to this foreign creature that, as we see in the miniature, he allows her to ride him like an animal into Alexander's court (Figure 3). A woman thus consigns "the best clerk in the world" to bestiality (line 449), to the very place where his own teaching had relegated her. His book learning discredited and his mastery debased, Aristotle becomes the object of ridicule. As Cato's sentence sums it up: "It is disgraceful for the doctor when he convicts himself through his own fault" (Turpe est doctori cum culpa redarguit ipsum; line 521).

In its simplest terms, the Lai d'Aristote follows the proverbial wisdom: "Nature is worth more than nurture."[2] This lesson of a dominant nature runs implicitly along gender lines. With woman on top, in a position suggesting her sexual dominance, the natural is identified with the feminine (Figure 3). This coding of the nature/culture opposition suggests other feminine/masculine polarities. One maxim associated with the Lai reads: "Female cunning deceives even the most learned," and another: "Do not let woman's power trespass on your mind or enter into your spirit, or you shall be confounded."[3] Any intelligence ascribed to women (astutia ) is defined a contrario , as a threat to men's. It rivals the trait distinguishing the clerk. According to these maxims, the Lai stresses the polarity between men's reason and women's nonrational intelligence. The "boy meets girl" plot is transformed into a meditation on the feminine rapport with intellectual authority and knowledge. Judging from the Lai 's widespread circulation and the iconography and commentary that it inspired, this meditation touched a nerve in the medieval clergy.[4] It provoked concern that—like these amusing marginalia—underlies their thinking.[5]

In its largest terms, then, the Lai raises questions about mastery. It thus rejoins a longstanding philosophical inquiry into the links between intellectual capital and authority—in Foucauldian terms, the power/ knowledge nexus.[6] And it reformulates that inquiry specifically in terms of the feminine. When women are involved, what exactly does it mean to be masterful? Mastery refers first of all to a type of competence or expertise. For medieval clerks, as for us, it entails working through a particular body of material and gaining control over it. With mastery comes a certain assurance, since the masterful command of material itself comprises a mode of power. According to one Aristotelian axiom cited often in the late Middle Ages: "It would be strange if, when a man possesses knowledge, something else should overpower it and drag it about like a slave."[7] Already visible here is the related issue of domination. Mastery precisely evokes the struggle between people that leads some to dominate and others to submit. Understood sociologically as well as intellectually, it refers to the perpetual give-and-take between people. It exemplifies what Augustine called "the burning passion for domination." (cupiditas ardens dominationis ).[8] From the first encounter between individuals or groups, each party attempts to gain the upper hand. The dynamic of dominance involves contending with the other person in the attempt to overcome his or her difference. In the Hegelian terms that color any contemporary analysis of mastery, it involves a sparring match whereby each tries to reduce the human qualities of the other and thus emerge master vis-à-vis

a subordinate object.[9] The struggle is ongoing and the contradiction apparent, for each party depends on the need to be validated as a person by the antagonism or resistance of the other.

However separate and distinct these two senses of mastery are, the Lai d'Aristote brings to the fore their charged interrelations. With its scene of the master mastered, it discloses the clerical fear of losing intellectual control through women, and at the same time it reveals the pressures to maintain that control over them. By communicating the inverse scenario, the Lai suggests the impetus to command women effectively. It thus invites us to consider the ways masterful intellectual authority can become a form of domination. It focuses our attention on the process whereby what is valued positively, the production/possession of knowledge, can translate negatively into a mastery of women.

This process has occasioned various feminist reflections on mastery.[10] Given the potential for knowledge as an instrument of domination, there was reason to investigate how women were implicated. In Aristotelian terms, the question was: if women have been dispossessed of knowledge historically, does it follow that they could thus be dragged about like slaves?[11] Feminist theory began by analyzing mastery in its twofold sense as a normative system of relations elaborated and enacted principally by men. Such reasoning led some feminists to label both senses of mastery pejoratively. Mastery is deemed problematic because it represents a masculine way of leading an intellectual life. Correspondingly, women are seen to assume masterful intellectual authority reluctantly, since to do so brings with it the legacy of their subordination.[12]

By imputing to men the conversion of masterful expertise into domination, this critique runs into its own difficulties. The danger lies in confirming that conversion. While feminists have argued that intellectual authority can be used disadvantageously against women, by labeling it a "masculine" phenomenon they reinforce the pattern of disallowing women's intellectual mastery. "Just as the child's attempt to impose control and order on its world cannot be equated with exploitative domination," Toril Moi reminds us, "it is singularly unhelpful to see all forms of intellectual mastery simply as aggressive control and domination."[13] To do so is to run the risk of rejecting the potential for masterful expertise together with its abuse. Further, this critique is liable to confuse the instruments of mastery as domination with its causes.[14] The critical challenge lies instead in examining the logic undergirding the twofold notion of mastery. When Christine de Pizan calls her polemical participation in the Querelle de la Rose "nonhateful, a form of solace that outrages no one," she avoids an ad

hominem critique and concentrates on the injurious language of the Rose itself.[15] In her study on the Querelle des femmes , Joan Kelly targets "not men, but misogyny and male bias in the literate culture," thereby echoing Christine's sentimen.[16] For medieval and contemporary critic alike, analyzing the ways authoritative traditions of knowledge work against women means critiquing the ideological system that individual masters represent.

In juxtaposing such feminist critiques of mastery with the Lai 's tale of Aristotle upended, I wish to situate the problem of the master in a specific context. My purpose is to introduce a historical framework for our theoretical discussion and thus to substantiate what Foucault has warned is notoriously insubstantial.[17] I shall argue that the medieval structures of mastery so tellingly displayed in the Lai provide a matrix for subsequent configurations. It was the scholastic institution of the master (magister ), developed over the course of the twelfth century, that played a significant part in cultivating the affinities between mastery as intellectual authority and mastery as mode of domination. And it did so by casting the intellectual enterprise agonistically. As Martin Grabmann has taught us, the process of learning in the high Middle Ages was fundamentally defined by struggle.[18] Whether in a scholastic context or its vernacular counterpart, acceding to the station of master was, quite literally, a fight: "crude behavior, insults, threats, 'it came even to blows.' "[19] The very language of learning was imprinted with this aggressiveness. Altercatio, conflictus, disputatio, querela : many medieval pedagogical terms bespeak a potential for violence.[20]

This agonistic character of learning created the circumstances for converting intellectual authority into a mode of domination. Indeed, in Walter J. Ong's view it favored that conversion.[21] To what extent that particular conversion concerns women, however, is less clear. In the role-reversal game of the Lai d'Aristote , where are the signs of women's intellectual struggle? How does the dominating impulse that animates learning touch them? In order to answer these questions, we need first to study the dynamics between the medieval master and his disciple.

Learning to Dispute

Appearing with the twelfth-century schools, the magister occupied a prestigious position in the rarefied milieu of the literate clergy.[22] And with the foundation of the universities in the thirteenth century, he

grew to be an ever more prominent figure.[23] His official title distinguished him as an authoritative scholar who presided over the canonical texts. At the same time, the licentia docendi invested him with a specific pedagogical responsibility. The master was in charge of instructing groups of student-disciples and of initiating them in a world of scholarship. This initiation staged a confrontation of wills that was to culminate in the disciple bending to the master. According to the popular clerical manual De disciplina scholarium : "He who has not learned that he is subjugated [to the masters], could never come to know himself as master" (qui se non novit subjici, non noscat se magistrari).[24] In vernacular descriptions as well, the master/disciple rapport develops out of a sense of rivalry and respect. A late-thirteenth-century didactic work, the Livre d'Enanchet portrays just how charged that rapport is:

Et si-l doit metre ainz au boen meistre q'au mauvais, por ce que-u boens meistre est mout utel chose au deciple. Et il doit sorestier a la dotrine son maistre; por ce q'ausi corn la grotere de l'aigue chaant [chaut] d'en haut cheive la piere dure, vance l'usage a savoir ce que-u cuers de l'ome ni voldroit maintes foiees. Mes il doit mult honorer son meistre, por qu'il est lo segond signe de science, et doit mult enquerir sa dotrine et noter ses paroles et son chastiemant.[25]

And he should dedicate himself to a good master rather than to a bad one, since a good master is extremely useful to a disciple. And he should attend to the doctrine of his master, for just as a drop of water fallen from above pierces the hard rock, so too the use of knowledge hits a man's heart where it is oftentimes not receptive to it. But he should greatly honor his master, since he is the second sign of knowledge and he must seek energetically after his doctrine and take note of his words and teaching.

As "lo segond signe de science," the master embodies the world of learning (dotrine ), outfitting the disciple for an intellectual life. Yet that preparation involves yielding to the master's authority as well as to his knowledge. The Livre d'Enanchet shows the master handing down a chastoiement . This Old French term, echoing the Latin castigare found in the Disciplina , combines the notions of instruction and latent strife: one goes with the other. Imparting a doctrine entails a type of castigation or chastisement. This castigation was directed toward both men and women; contemporaneous didactic texts such as Le Chastoiement d'un père à son fils and Le Chastoiement des dames are built on one and the same model of the master taking the student in hand.[26]

This sense of discipline discloses the tensions informing the master/ disciple relation. While the disciple struggles to attain the master's respect and wisdom, the master in turn castigates him. Contention fuels their exchanges and, paradoxically, binds the two figures together. If the surviving accounts give us any indication, such contentious relations ruled university life.[27] Even the latter-day humanist critic Vivès would describe the scene as all "that scholastic shadowboxing and contentious altercation" (scholasticasque illas umbratiles pughas et contentiosas altercationes).[28] The medieval master inducted the disciple in an intellectual life whose characteristic methods were conflictual. The question-and-answer modes of instruction (quaestiones ), the disputations (disputationes ) that began the debates pitting masters against students (quodlibeta )—such standard dialectical methods trained the student to work against his master.[29] If the disciple was ever to assert himself, he had to proceed adversarially—in John of Salisbury's words, through "verbal conflict"—mounting challenges and refutations of what the master put forth.[30]

These challenges were never meant to jeopardize the institution of mastery. On the contrary, the entire agonistic process was geared to outfit the disciple for the master's role.[31] It distinguished those few disciples who would eventually assume the magister title from the many others who failed to meet the test. The sustained disputations sanctioned certain disciples as members of the scholastic elite. In the end, the chastoiement validated them as authorities able to discipline others. In this, the master/ disciple engagement resembles the sparring between knights, for there too the clash provides a mechanism for bonding that secures both men in the same courtly, chivalric roles.[32]

No more telling example of the disputational dynamic exists than the case history of Peter Abelard. The dialectical method of thought that he pioneered in his treatise the Sic et Non was illustrated uncannily in his own dealings with his peers: his unceremonious rejection of his master, Anselm of Laon, his attacks against a rival master, William of Champeaux, his sparring with his own followers. Abelard exemplifies the way the medieval system of intellectual mastery functioned by creating conflict so as to better establish control of intellectual problems. The difficulty in mastering a particular body of knowledge was played out through disputation. And far from dividing the masters and students definitively, their disputatiousness acted to consolidate their caste. The more bitterly they fought among themselves, the more tightly they closed ranks and cemented their control over intellectual matters. Abelard's reputation makes this clear. However he depicted himself as renegade and outcast, medieval posterity identified him as one of the masters' own.[33]

Abelard's case is also important because it reveals how the feminine begins to inform the disputatiousness of medieval masters and disciples. Intellectual traditions in Europe had long typed knowledge as a woman (scientia ), and its highest form, wisdom, as a female deity (sapientia ). Like many other masters straight on through the Renaissance, Abelard dedicated himself to the goddess of wisdom, Minerva. "I gave up completely the court of Mars so as to be brought up in the lap of Minerva. . . . I put the conflicts of the disputation over and above the trophies of combat."[34] Abelard's description of his entry into intellectual life gives us a telling sense of how the pursuit of knowledge is connected with the feminine. Embracing wisdom implies coming into contact with a woman. Yet this embrace is not incompatible with aggressive impulses. Although Abelard renounces the god of war, he does not relinquish the martial arts. For him, the bellicose and the feminine come together in the form of the disputation. Under the aegis of Minerva, verbal battles are to be waged. That Abelard chooses this goddess as mentor shows how the scholastic activity of disputing comes to be figured through women.

But if intellectual mastery is represented in part through the feminine, where do women figure in? We come back to the question of women's encounter with clerical intellectual life. Can they participate in the master/ disciple disputation? Abelard's explosive experience with Héloïse hardly bears this out. His tutelage of her was short-lived, leading quickly to their sexual relation. In the vernacular domain, the picture is little different. In the Livre d'Enanchet , for instance, the master who debates with his disciple puts forth the following doctrine (la dotrine dou clers ): "It is better to sit in a corner of the house that is not in the throughway; not like a woman who wags her tongue" (il est mieuz seoir en un angle de sa maison qe n'est en chiés comun. Ne corn famme laengueice! Fiebig, 7).[35] This portrait of the model clerk distinguishes him from the woman who talks too much. And it spatializes his distinctive role. Whereas the woman plants herself in the middle, the clerk is recommended to place himself apart, in isolation. Such a scene, I would suggest, builds on the standard outline of the social hierarchy of roles in Andreas Capellanus's De amore : "In addition, among men we find one rank more than among women, since there is a man more noble than any of these, that is, the clerk" (Praeterea unum in masculis plus quam in feminis ordinem reperimus, quia quidam masculis nobilissimus invenitur ut puta clericus; II, 1; Parry, 36; Pagès, 10). The fact that the clerk inhabits a separate space underscores his unique position. Not only does he represent the "most noble" man, but he has no female equivalent. In the clerical schema of Capellanus or the Enanchet , there are few signs of women assuming the stance of disciple.

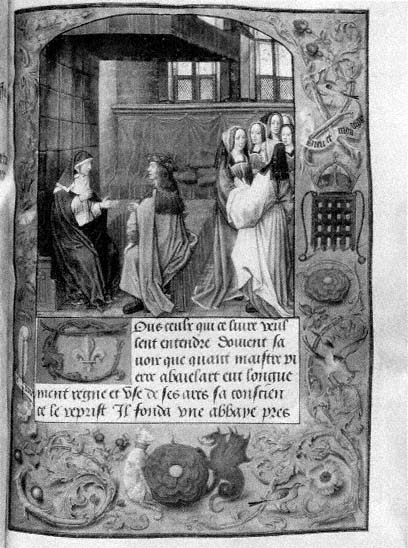

4. The duke and duchess of Brabant and the master of the Consaus d'amours .

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 2621, fol. 1.

Courtesy of the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

Such definitions of clerical life give us a first glimpse into the vexed position of women vis-à-vis intellectual mastery. They are at odds with the clerical role. Yet they are not completely evacuated from its domain. The inaugural miniature from the Consaus d'amours , a late-thirteenthcentury didactic treatise, exemplifies this dilemma (Figure 4). The woman, the duchess of Brabant, sits side by side with her lord the duke—an apparent partner in the lessons the master pronounces.[36] But the text that follows relays a debate engaging the men alone. Designed implicitly as a master/ disciple dialogue, it leaves little room for her. In fact, the insignia of the various figures in the miniature confirm this: while the book links the duke to the academic learning of the master, the scroll identifies the woman with the oral. The duchess appears ready to repeat the master's formulas but unable to engage with them fully and make them her own. The structure of the master/disciple dispute seems to both accommodate women and disqualify them.[37] While included theoretically as part of the proceedings, they are nonetheless blocked from participating in its work: mediums of the disputation, yes; real contestants, no.

A Clerkly Savoir Faire

This precarious position of women is established in Latin and vernacular literature in texts such as the Latin Concilium Romarici montis and the Old French Jugement d'amour .[38] These two related twelfth-century works offer a paradigm of women's circumscribed role in the world of intellectual mastery. The Concilium and the Jugement dramatize a disputation on love conducted exclusively by women. One side argues that the clerk is the best lover, and the other, the knight. Locked in an intractable quarrel, the female opponents bring their cases to be judged; in the Concilium before an assembly of women, and in the Jugement before the God of Love. Opinions are unanimously in favor of the clerk. Both these texts are obvious propaganda pieces for the clergy.[39] Yet the degree to which women advance its cause is surprising. Why this recourse to female surrogates? Why should clerical discourse articulate its own privileged claims by way of women?

From the outset of the debate, this surrogacy looks incomplete: "No one called a man is admitted to that place; nevertheless some were present who had come from faraway; they were not laymen, but respectable clerks" (nemo qui vir dicitur illuc intromittitur. Quidam inde aderant, qui de longe venerant, Non fuerant laici, sed honesti clerici; Concilium , 10–12). The androgynous clerks appear only on the sidelines. Yet such an appearance makes clear that while they do not speak their part, they are still directing it through a female agent. Women are deemed both capable and incapable of assuming the clerks' position. Later on in the narrative, the limits of their intermediary role are specified: "For the women, the art is in knowing the things of love, but they are ignorant of what a man should know how to do in practice" (Harum in noticia ars est amatoria; Sed ignorant, opere quid vir sciat facere, lines 34–35). The distinction here is between women's familiarity with the subject of love and "manly" clerks' ability to exploit it. One talks, the other acts on his knowledge. In effect, the women champion all those clerkly traits that the knight does not possess, especially knowledge: "I beseech you to love clerks above all, by whose wisdom everything is disposed" (Precor vos summopere clericos diligere, quorum sapientia disponuntur omnia; Concilium , lines 186–87). Or as the clerk's advocate, Blancheflor, argues in the Jugement : "The clerk knows more about courtliness, he ought to have a girlfriend more than anyone else, even more than the knight" (Ke clers set plus de courtoisie et ke mieus doit avoir amie ke autre gent ne chevalier; lines 249–51).

This clerkly brand of knowledge is presented in academic terms: recorded in writing, developed through commentary and disputation. Love is thus for the clerk less a physical affair than one of learning. Even the knight's advocate notes this: "When your lover is at the monastery, he pores over his psalter, he turns over and over again the parchment, and for you he makes no other play" (Quant vos amis est au moustier, torne et retorne son sautier, torne et retorne cele piel: pot vous ne fait autre cembiel; Jugement , lines 115–17). From the opposing position, the clerk's commitment to written texts is also figured as powerful, if not allengrossing.

Given the clerk's superior knowledge, what exactly is he alleged to know? While the image of the clerk with his psalter suggests theological learning, by the end of the Concilium he is associated with the secrets of women (abdita ). The history of ideas in the West has long identified secrets as a choice intellectual category and typed them, like the Minervan myth of knowledge, invariably in feminine terms.[40] Whether we look to the Greek philosopher contemplating the mysteries of nature or the Renaissance man of science probing the material world, the quest for knowledge habitually seeks a feminine object. In medieval culture, this fascination with feminine secrets was widespread. Witness the pseudo-Aristotelian Secretum secretorum or the Secres as philosophes , two compendia of the most recondite items of scientific knowledge that maintain this feminine character.[41] Or the widely known thirteenthcentury gynecological texts, Secreta mulierum (The Secrets of Women ).[42] In contemporaneous vernacular literature as well, women's secrets were the quarry par excellence. Andreas Capellanus's De amore , for one, contends that the would-be lover should begin by tracking them: "Presently he begins to think about the fashioning of the woman and to differentiate her limbs, to think about what she does, and to pry into the secrets of her body" (Postmodum mulieris incipit cogitare facturas et eius distinguere membra suosque actus imaginari eiusque corporis secreta rimari; Parry, 29; Pagès, 3). This probing into secrets is also emphasized in Drouart La Vache's French version of the De amore :

En son cuer recorde et ramenbre

La faiture de chascun menbre,

Les venues et les alees

Et cerche les choses secrees.

(Li Livres d'amours , lines 237–40)

In his heart he recalls and remembers the form of each member, its comings and goings, and he searches for their secrets.

The lover's fantasy about different members of the woman's body heightens the desire to get at her secrets. The greater the reflection on them, the greater their lure.