Chapter Sixteen—

Storm over Baikal

More than any other issue, projects that threatened the integrity of Soviet, and especially Russian, waters elicited the passionate opposition of all varieties of environmentalists, from the high intelligentsia to the newer Russian nationalists. From the 1930s on, the megalithic water projects beloved by Stalin had been managed by the GULAG administration under the immediate supervision of the infamous major general S. Ia. Zhuk, head of the Main Hydrological Construction Agency of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (later, the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of State Security). Beginning with the Baltic–White Sea Canal, the desolate banks and byways of tens of watersheds yielded to the weary thrusts of hundreds of thousands if not millions of zeks (prisoners) whose shovels and bare hands recarved the land into new waterways, inland seas, and hydropower stations. The orgy of hydroelectric and canal construction, which only began to subside during the 1950s, left a legacy that rivaled the Tennessee Valley Authority in scope: the Moscow-Volga Canal, the Volga-Don, the Rybinsk hydrostation and reservoir, and the "reconstruction" of the Dnepr river. It also left another, darker legacy. Perhaps 120,000 died on the White Sea Canal project alone.

At least some nature protection activists made the connection between Stalin's violent transformation of the land and his violent, instrumental treatment of humans. Anton Struchkov provides the example of Andrei Petrovich Semënov-tian-shanskii, whose close friend, the sixty-seven-year-old Andrei Dostoevskii, nephew of the writer, was one of those deported to the White Sea Canal project. "Happily," writes Struchkov, "after a year of labor Andrei Dostoevskii managed to return to Leningrad, but this experience was enough for his friend to realize that violence to nature and violence to people literally went hand in hand."[1] Semënov-tian-shanskii went on to

publicly oppose the massive hydroelectric projects at a special conference on wildlife management in February 1932, an act of high civic courage.[2]

For the intelligentsia, therefore, even after Khrushchëv dismantled the forced-labor system in the mid-1950s, hydroelectric stations, canals, and other gargantuan earth-moving projects continued to resonate as icons of Stalinism, recalling both the repression and the megalomania associated with the dictatorial system. After the "thaw," though, it became possible to speak out against them.

For first-generation educated Russians the most objectionable aspect of the big water projects was their threat to Russian villages and historical monuments. Whereas twenty years earlier newly minted engineers or young "proletarian writers" would have looked on the huge dams, canals, and reservoirs with patriotic pride, by the 1960s these same kinds of people had become increasingly distressed that "progress" and "modernity" had been purchased with the destruction of their spiritual home. For people of this background, the taiga represented the last remaining hearth of Russian culture, and it was on the northern and Siberian forests that the dam-builders and planners had focused their attention from the mid-1950s. At the center of it all was Chivilikhin's "luminous eye of Siberia," Lake Baikal.

Unlike any previous environmental struggle, the fight to protect the vast lake from physical alteration and industrial pollution embraced not only the various branches of committed nature protection activists but a broader public as well. Such public participation imbued the struggle around the lake with a larger meaning as an incipient general protest against the rulers' abuses of power.

For those who have seen Baikal, adjectives fail. One of the best short descriptions of the lake has been provided by geographer Philip R. Pryde:

Lake Baikal, located . . . just north of the Mongolian border, is perhaps the most remarkable freshwater lake in the world. Geologically, it lies in a huge graben (a structural depression between two parallel fault systems), and is approximately 700 kilometers long. The lake has the distinction of being the most voluminous freshwater body in the world (23,000 cu. km.), and the deepest as well (1,620 m.). Lake Baikal's main significance is not just its size, however, but rather its biology. In its unusually pure waters can be found over 800 species of plants and about 1,550 types of animal life. More importantly, the majority of these are endemic, making Lake Baikal an object of worldwide scientific importance.[3]

S. Ia. Zhuk's hydraulic empire was the first project to threaten large-scale changes to the natural conditions of the lake. "In the bowels of this, one of the country's most politically potent institutions [the S. Ia. Zhuk

All-Union Hydrological Planning and Scientific Research Institute—Gidroproekt], an authentically diabolical plan was hatched and developed," wrote novelist, journalist, politician, and Baikal activist Frants Taurin: "to blow up the mouth of the Angara and to lower the level of Baikal by several meters."[4]

Chief engineer N. A. Grigorovich of the Angara Sector of Gidroproekt intended to detonate an explosion—50 percent larger than that at Hiroshima—to allow greater water flow from Baikal to the hydroelectric stations downstream on the Angara River, into which the lake drained. The plan is described by Paul Josephson in his study of the Siberian branch of the Academy of Sciences.[5] Josephson also authoritatively identifies the important role played by Siberian scientists and writers in opposing this and other schemes. Exploring the story in detail Josephson became perplexed by an apparent paradox: scientists with impeccable political credentials, a strongly patriotic outlook, and plain (peasant) social origins, such as geologist Andrei Alekseevich Trofimuk, assumed key leadership roles in the defense of Baikal. We must disaggregate the different iconic meanings of the lake to appreciate why the reactions to its despoliation were so broad and passionate.

Grigorovich's plan met its first resistance at the August 1958 conference on the development of the productive forces of Eastern Siberia sponsored by Academy of Sciences' Council on Productive Forces (SOPS), held in Irkutsk. The giant conference, with 2,377 scientists and others in attendance, was preceded by a week-long series of regional miniconferences, in Chita, Krasnoiarsk, Ulan-Ude, and other localities, with an aggregate attendance of 5,690.[6]

Mikhail Mikhailovich Kozhov, an academic specialist on the fish and mollusks of Lake Baikal, was one of several to rebut the arguments laid out by Grigorovich, who also spoke at the Irkutsk conference. While arguing on scientific grounds that the Baikal fishery would suffer from lowering the lake's average level five meters, a likely consequence of the Grigorovich plan, Kozhov concluded with an admonition colored by an aesthetic, moral, and perhaps nationalist sensibility: "We don't have the right to destroy the harmony and beauty of this unique gift of nature." Kozhov was backed by the massive assemblage, which voted to support zapovednik status for the lake and a ten-to fifteen-kilometer radius of woodlands, and which also noted that "the unique value and significance of Lake Baikal with its unique nature and . . . the need to transform Baikal into a health resort and center of tourism" mandated its "strict protection . . . from pollution by industrial wastes."[7]

The outspoken opposition of Siberian scientists and even politicians did not go unnoticed by the Party watchdogs, who reported to the Central Committee: "In a portion of the presentations, especially in the talks of a number of enterprises and institutions of Eastern Siberia, regionalist tendencies

came to the surface, for example in the discussions over questions of energy production linked with Lake Baikal."[8]

In Irkutsk, the largest city near the lake, city leaders raised not a whisper of protest to the Grigorovich plan. "Many of the local notables even approved of the project," recalled Frants Taurin, who himself once served as chair of the municipal soviet (mayor) of Iakutsk in the early 1950s. "However," he went on, "in a complete surprise for those in power, public opinion came alive. For those days, that was, let us say, a completely atypical development."[9]

Taurin attributes the vigorous response of significant segments of Irkutsk society to the city's unique urban traditions. Much like the social milieu of the field biologists, in Iakutsk as late as the 1950s the city's intelligentsia still survived largely intact and in significant concentration. These were the descendants of generations of tsarist political exiles: Decembrists, Poles deported in 1830 and 1863, populists, anarchists, Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, and Socialist Revolutionaries. "These were people who imbibed the idea of personal honor and a feeling of their own dignity, so to speak, with their mother's milk and were able to uphold this dignity through the black years of Stalin's arbitrary rule" judges Taurin, although he notes that many perished in the process.[10]

Covering Eastern Siberia in 1958 for Literaturnaia gazeta , Taurin and a colleague from TASS, Aleksandr Gaidai, decided to help the Iakutsk civic activists bring their message to the national press. After consulting with Grigorii Ivanovich Galazii, head of the Academy's Siberian branch's Baikal Limnological Station (later Institute) on the lake at Listvennichnoe (Listvianka), who equipped the journalists with scientific data and arguments, Taurin and Gaidai drafted a letter to the editor of the Literaturnaia gazeta and circulated it to collect signatures. The fact that hydroelectric engineers, including the director for construction of the Iakutsk Hydroelectric Station and deputy to the RSFSR Supreme Soviet, the station's chief engineer, and the project's Party committee head all signed gave the letter unusual weight. Galazii, Taurin, Gaidai, and eight others were also signatories. And on October 21, 1958, "In Defense of Baikal" appeared. The letter was evidently based on Galazii's projections of how the Grigorovich plan would affect fisheries, marine fauna and flora, the Angara floodplain, water supplies, and even railroad bridges in the area. Journalistic and literary flourishes were kept to the bare minimum, but the letter powerfully asserted that Baikal "belongs not only to us but to our descendants." The closing appealed for the active backing of "broad public opinion."[11]

The appeal touched a nerve in the newspaper's readers. Within a month more than one thousand letters from all over the country poured in to Literaturnaia gazeta , many bearing the signatures of whole groups and collec-

tives.[12] Dazzled by the reaction, the paper's editorial board lauded Taurin's "material" as the best item published that month.[13]

Beginning in July 1956 Literaturnaia gazeta had led the way in the press's discovery of environmental issues, and in February 1957 it even sponsored a large conference to discuss the state of the zapovedniki and of game management.[14] That same year even the Pravda editors expressed interest in the issue, inviting Iu. K. Efremov to make a presentation before their board. For reform-minded editors environmental issues carried relatively low political risk while at the same time bolstering Soviet citizens' tentative efforts to find their civic voices and to exercise political initiative. Before the reform press's skewering of Mikhail Mikhailovich Bochkarëv there had been a good eight years of press involvement on environmental issues: zapovedniki , Kedrograd, and, most crucially, Baikal.

Other new dangers to the lake were now being identified publicly. Also in 1958 an influential book was published in Iakutsk: Okhraniaite pirodu! (Defend Nature! ) Written the previous fall by game management specialist Vasilii Nikolaevich Skalon, the book, while concentrating on the depletion of Siberian forests and game, was probably the first to publicize threats to the lake. True, Skalon only pointed out the risks of continuing to allow huge quantities of cut logs to sink while being floated to port, but the book's importance lay in its recognition that Baikal and Siberia were neither too large nor too remote to withstand the advance of modern industrial society.[15]

Finally, in 1958 the public learned of plans for a major military-industrial installation to be built on the shores of the lake. The proposal—to build two factories for making viscose cord for airplane tires on Baikal's southern shore and main tributary, using the lake's ultrapure water—is now notorious. Like the story of the desiccation of the Aral Sea or the Kara-Bogaz Gol, it has become a parable of the inflexibility and myopia of the Soviet production system.

Where the Grigorovich plan threatened the lake's biota through an alteration of water levels, especially near the shoreline, the military factories raised the specter of chemical and thermal pollution, which could wipe out many of the species of fauna in the lake. Of course, the public was not told about the strategic nature of the original proposed factory. Rather, the plant was depicted as one dedicated to producing high-quality paper goods. The nature of the product made the environmental risks and costs seem that much more intolerable. Even those who knew the plant's true original purpose were constrained to refer to it in their public criticism as a "paper and pulp" plant, which, ironically, it eventually became.

The battle was waged, for the first years, on the pages of the Literaturnaia gazeta . Indeed, Taurin learned of the "cellulose" project at the same editorial meeting that lavished praise on his drafting of "In Defense of Baikal."

Editor in chief Sergei Sergeevich Smirnov boldly declared that Baikal was "our story," and approved travel expenses for the journalist to pursue the story. While in Moscow Taurin arranged for an interview with Nikolai Nikolaevich Nekrasov, chairman of SOPS, the Academy's Council for the Study of Productive Forces.[16] Nekrasov revealed to the journalist the true military purpose of the factory and explained that although Lakes Onega, Ladoga, and Teletskoe had equally pure water, the pine forests around the first two were largely logged out, and around Teletskoe the predominant conifer was spruce, whose molecular structure was unsuitable for the tire cord.

To date no single author of the plan has been identified. All we know are the names of the chief engineer, Boris Aleksandrovich Smirnov, of Sibgiprobum (the Siberian Planning Institute for the Paper Industry) and of G. M. Orlov, who had been serving as the Soviet minister of the pulp, paper, and woodworking industries (variously renamed) since World War II, under whose auspices the plants were built. Taurin insinuated himself into Smirnov's confidence, feigning ignorance of the scientific issues involved with the viscose plant (although Taurin had once studied organic chemistry at Kazan Polytechnical Institute in the fur and tanning department). Smirnov allowed Taurin (who worked under a pseudonym) to examine all of the technical documentation under the supervision of the engineer's assistant, one Viacheslav Maksimovich. On parting, Smirnov asked Taurin whether the assistant was able to resolve any misgivings Taurin may have had about the project. Taurin replied, "Viacheslav Maksimovich provided highly knowledgeable answers to my questions. He raised my chemical literacy to a completely new level. I believe that, basically, the situation is now clear to me." Still unsuspecting, the engineer effused, "That's just wonderful!" as Taurin left for Moscow.[17]

Taurin's hard-hitting and technically literate piece "Baikal Must Become a Zapovednik ," published on February to, 1959, took on all of the lake's enemies at once. "With all due respect to the work of the planners," Taurin wrote, "it is impossible to renounce the conviction that they are pursuing an erroneous and harmful 'line.'" How much difference in water quality, asked Taurin, could there be between the lake itself and some downstream point of the Angara, into which Baikal empties? Weren't there forests enough in Siberia without laying hands on the lake's watershed? Interestingly, noted Taurin, those from Grigorovich's Gidroproekt who responded to the letter "In Defense of Baikal" supported the idea of turning the lake into a vast zapovednik and condemned the prospect of industrial pollution of the lake, overfishing, logging the watershed, and killing the freshwater seals. Their only criticism of the letter was the signatories' "wrongheaded" opposition to detonating the mouth of the Angara. Conversely, employees of Giprobum, which held responsibility for planning the viscose plant, were equally adamant in their opposition to Gidroproekt's explosion. Taurin facetiously

mused that, had there been time to elicit the position of the logging interests, they would doubtless have opposed both the industrial pollution of the lake and blowing up its outlet. "In the abstract, everyone stands for protecting Baikal," wrote Taurin, "under one critical condition—that such protection would not affect their bureaucratic interests. But that is the crux of the matter. Concern for Baikal, with preserving its nature, is not a matter to be entrusted to bureaucratic agencies to resolve; it must be resolved by the entire people." Noting that at the conference on productive forces of Eastern Siberia "our country's best scientists . . . spoke out for declaring Baikal and adjacent zones a state zapovednik ," Taurin concluded his article with the admonition that the lake "not only belongs to us, but to our descendants," making its preservation a moral duty and not simply a practical exercise.[18]

Shortly thereafter, Literaturnaia gazeta published a collective letter "To the Defense of Baikal!" from the leaders of the USSR Academy of Sciences' Commission on the Protection of Nature, Dement'ev, Shaposhnikov, A. A. Grigor'ev, and staffers.[19]

Perhaps under pressure from this combination of scientific public opinion and a newly awakened press, in April 1960 the USSR Council of Ministers adopted a law on water pollution requiring that pollution abatement technologies be in place and working before new factories began operations. On May 9, the RSFSR passed specific legislation designed to insure the protection of Lake Baikal and its basin, prohibiting the start-up of the Selenginsk and Baikal'sk factories until waste purification installations were operational.[20]

The issue refused to go away, however. In July 1960, Balzhan Buiantuev, a Buriat geographer with the East Siberian branch of the Academy of Sciences, published a brochure critical of development of the lake's basin, while the Fourth All-Union Conference on Nature Protection opposed any discharges of waste water into Baikal, even after treatment.[21] Moreover, by 1961 the Komsomol daily paper, Komsomol'skaia pravda , was in a bidding war with the Literaturnaia gazeta to be the defender of the environment within the Soviet press. It also needed to make moral "reparations" to the nature protection community for the tactless publication of the crude satire "Protected Tree Stumps" following Khrushchëv's January 1961 speech. The answer was Galazii's "Baikal Is in Danger," published as a letter on December 26, 1961. As Josephson notes, Galazii's letter "spilled the beans" on the nature of the chemical effluents that the two plants would discharge.

Literaturnaia gazeta lost an opportunity to recapture its story by failing to publish Gennadii L'vovich Pospelov's "Musings on the Fate of Baikal," which the senior researcher at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics at Akademgorodok offered to the newspaper in a letter of February 8, 1963. It was snapped up by Sibirskie ogni , which ran it in its June issue. Pospelov's

accompanying letter to the editor of Literaturnaia gazeta was unexpectedly revealing, for it confessed that the emphasis on economic arguments against the cellulose plants in his article was "to make the argument more effective." His letter was also the first in print to alert the general public to the danger of the siting of the plants along the virtual epicenter of the Mongolian—Sea of Okhotsk seismic zone. (These arguments had been deployed in April 1962, when a prestigious group of academicians including Sukachëv, M. A. Lavrent'ev, and others wrote to the USSR Council of Ministers warning of the devastating consequences of an earthquake at the future plant site. They were soon joined by Academy president M. V. Keldysh, who sent his own letter.)[22] The real objections of the author, however, who claimed to speak for nauchnaia obshchestvennost' , was that the pollution of Baikal represented a loss to science and a blow to the international prestige of Russian science.[23]

If indeed Pospelov sought to downplay scientific public opinion in the article as it appeared in Sibirskie ogni , he was not entirely successful. Readers, the author doubtless hoped, would find themselves as infuriated as he by the wanton disregard for scientific expert opinion. Neither the conclusions of an all-Union scientific conference of late summer 1962 chaired by geographer I. P. Gerasimov nor the repeated objections of both the USSR and Siberian branch of the Academy of Sciences had the slightest effect on the prosecution of the project.[24]

"The whole matter turns on our different understandings of benefits to the state and duties of the state," ventured Pospelov in a rather daring political challenge to the Party's claim to a monopoly on political "vision." "We are a society actively creating the future of humanity, and for that reason we must place on the scales of benefit and harm to the state the interests of our descendants as well," he continued. That included "the interests of all people on Earth." "The scientists who passionately spoke out against the faults of these projects, in opposition to the declared interests of the state, were in fact carrying out their moral duty and duty to the state." "Baikal is our national pride," he concluded, "and we must not permit bureaucratic mentalities to doom one of the greatest one-of-a-kinds on Earth."[25]

By 1963 yet other publications had joined in publicizing the lake's plight, and Oktiabr' in its April issue published what became the most famous of all the essays on Baikal, Vladimir Chivilikhin's "Luminous Eye of Siberia."[26] Reflecting the general awareness that Chivilikhin's article had generated a massive outpouring of letters, a letter to the journal's editor in chief, V Kochetov, from an aide to MOIP president Sukachëv explained that for years now a Baikal Commission had existed within the society and requested that the commission's scholarly secretary, Baikal activist Nikolai Pavlovich Prozorovskii, be permitted to acquaint himself with the correspondence, particularly from scientists.[27]

Oktiabr' had an even better idea. In a special section in October 1964 the journal published a selection of letters it had received on Baikal following publication of Chivilikhin's piece.[28] In a commentary prefacing the excerpts from this correspondence, the journal editors noted that "today the average person, wherever he or she may live, wants to know everything that is happening in his or her country. As a master of his/her fate, the average Soviet person often demands that his/her opinion, too, be taken into account."[29] Aside from quoting excerpts from the letters of such academic experts as Lev Zenkevich, a Moscow University ichthyologist, or A. S. Iablokov, an academic agronomist in VASKhNIL, the piece mentioned the article by Gennadii Pospelov in Sibirskie ogni and drew a parallel to the fight against the Lower Ob' Hydrostation, which found expression in a debate in the pages of the Party's theoretical journal Kommunist . To dramatize the depth of "public opinion" on the Baikal issue, the article listed some of the many scientific conferences and organizations from 1958 through 1962 that had gone on record to defend the integrity of the lake, as well as letters and public statements from a number of prominent scientists.[30] In a slap in the face to this scientific public opinion, "the organizations under criticism have not even found it necessary to respond," wrote Oktiabr' . "We don't know what they are thinking in Giprobum, Gidroproekt, the Irkutsk Sovnarkhoz, or the State Committee on the Pulp, Paper, and Woodworking Industries of Gosplan USSR with respect to the numerous outcries in defense of Baikal, but there is not even one lone document that disputes the conclusions of 'The Luminous Eye of Siberia.'"[31] Seeking support for its positions in the removal of Khrushchëv and the criticism of his style of governance, the journal announced that "now the Party has condemned arrogance and voluntarism in the solution of the serious problems of our economic development" and that decisions should now firmly rest on true planning and on science.[32]

The piece closed with a portrait of the economic system's continued irrationality. Informing the readers that even the justification for the plants had become obsolete, because viscose tire cord had been replaced by synthetics, "Once Again on the Subject of Baikal" noted with outrage that the factories were prepared to start operations—within the year—without pollution control equipment. "The poisoning of this Siberian sea, it may be said, has become inevitable," lamented the article. In an implicit challenge to regime claims that there was a rule of law in the USSR, the article noted that laws were on the books prohibiting the polluting of Baikal, but questioned whether they would be enforced: "Will the enterprises really be able to begin operations without pollution abatement equipment? Legally, they do not have that right. But what will happen in actuality? This remains an open question, and public opinion is waiting for an answer."[33]

With the ouster of the cantankerous Khrushchëv, the reform press and

the critics of Soviet environmental policies both became bolder. Even Pravda published an adventurously philosophical piece by correspondent A. Merkulov, who challenged the economic calculus of the "planners" with vivid descriptions of the social price tags of externalities and with a land-ethic perspective remarkably close to that of Aldo Leopold. "Is contaminating the Angara and turning it into a sewage canal really a measure without a cost?" he asked. "Supposedly nature takes no part in the debate between the planners of chemical and wood-chemistry enterprises and the defenders of the purity of waterways," he continued. "However, every time nature's interests are disregarded, it answers with dead rivers or lakes." Anticipating Christopher Stone's idea that nature had intrinsic interests that needed to be defended during development decisions, Merkulov added:

When the planning of enterprises on Baikal began, representatives of many agencies assembled. Some defended the interests of the fish, others the interests of the forests, and a third group the interests of the mining industry, but there was not a single representative to defend the interests of Baikal itself, to speak on its behalf. . . . The rivers and lakes await a law [to protect them]. They await a single master who will vigilantly stand watch protecting the interests of the state and the people.[34]

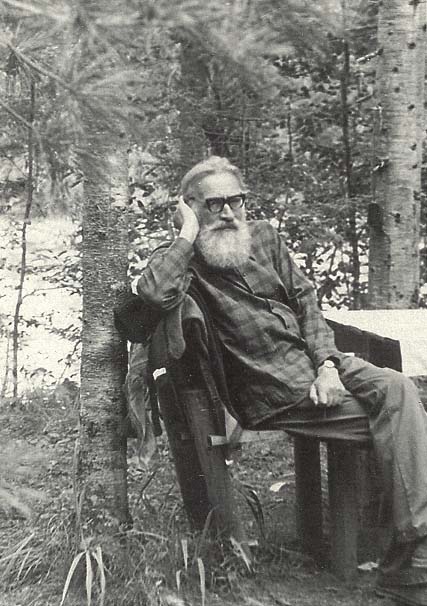

Literaturnaia gazeta got back in the game in February 1965 with a hardhitting piece by the writer Oleg Volkov titled "A Fog over Baikal."[35] An individual of rare resilience, Volkov (see figure 26) had once worked at the Greek Embassy in Moscow during the 1920s. Approached by the GPU to spy at the embassy, Volkov refused, whereupon he was arrested and served twenty-seven years in prison and the camps. Rehabilitated by Khrushchëv, Volkov began a successful writing career. He soon found his voice in the defense of living nature. A prerevolutionary-vintage intelligent himself, Volkov became the literary voice of the field biologists/nature protection activists. Boldly, Volkov cited U.S. trade figures that showed the declining production (and obsolescence) of cellulose-based cord, now replaced by nylon and especially polyethylene. Further, he proposed the heretical idea that no single ministry or agency, even representing industry, should have the right to determine the highest (indeed, exclusive) use of the lake. That was more properly settled by a broad public discussion of the issues.[36]

Baikal came tip as well at the Second All-Russian Congress of Writers, which met from March 3 to 10, and in the meeting's wake a group of writers—three Muscovites and five Siberians—published a collective letter in Literaturnaia gazeta on March 18. Otherwise unremarkable, the letter contained one paragraph that stood out in its linkage of Baikal, "the perfect model of the unduplicatable beauty of our own Russian nature," with Soviet—and Russian—patriotism.[37]

Figure 26.

Oleg Vasil'evich Volkov (1900–1996).

What next occurred was rare in the annals of Soviet politics: G. M. Orlov, Stalin's old minister of the paper and pulp sector and its boss as chair of the USSR State Committee on the Pulp, Paper, and Woodworking Industries, felt constrained to answer his critics from science, letters, and the press publicly, in the pages of the Literaturnaia gazeta .[38] Singling out for criticism the articles by Volkov and other Russian writers and Literaturnaia gazeta for publishing articles that "incorrectly portray the situation," Orlov made one notable concession: he claimed to support the same environmental values as his critics, promising that the factories "will not impair in the slightest either the purity of this unique volume of fresh water with its flora and fauna, or the cultural and esthetic value of the lake."[39]

Volkov immediately wrote a rebuttal to the minister in Literaturnaia gazetan .[40] Listing a series of earthquakes that had struck the Baikal region, Volkov again asked the project's defenders to speak to all the scientific objections, which he recatalogued in impressive detail. But the bottom line was the illogic of the situation; if cellulose cord was obsolete, then the Baikal plant had no strategic importance. Paper could be produced anywhere, so why place the lake in jeopardy? Orlov's attempt at damage control only inflamed and emboldened his opponents.

Two days later A. A. Trofimuk let loose with a sharp rebuttal to Orlov, also in Literaturnaia gazeta , entitled "The Cost of Bureaucratic Intransigence: A Reply to USSR Minister Orlov":

It would seem that Comrade Orlov as chair of the State Committee for Forest, Pulp and Paper, and Woodworking Industries . . . ought to respond attentively to the recommendations of scientists. But, as we see, Comrade Orlov is preoccupied with other things. Trying to save the honor of his uniform, he has tried to show with remarkable energy that all the questions of construction . . . were solved correctly and that the recommendations of the USSR Academy of Sciences do not deserve attention. . . . Comrade Orlov has gotten so carried away in his struggle that he doesn't even pause when spouting bald disinformation.

Expressing shock, Trofimuk confessed that the "methods [by which Orlov has been conducting this debate] are simply incomprehensible to me. To describe them is beyond my scientific capability." One thing, though, was certain: Orlov and his colleagues were "indifferent to the fate of the lake." Indeed, added Trofimuk, "I will even go one step further; in their actions I do not get the impression that they have any genuine concern either for the fate of that branch of industry entrusted to them. The fog of bureaucratic optimism, washing the shores of Baikal, must be swept away," he concluded, "and the sooner, the better."[41]

Taken together with the Bochkarëv affair, this spate of public denuncia-

tions of high officials by scientists was virtually unprecedented since the early thirties. Both Khrushchëv's thaw and his ouster go far toward explaining why this eruption took place in the late winter and spring of 1965. At that early date, most neither could see nor wished to admit the true conservative, repressive face of the Brezhnev regime.

Consequently, scientific public opinion had mobilized vigorously to defend Baikal. As early as February 25, 1963, Vera Varsonof'eva and N. P. Prozorovskii wrote to G. V. Krylov, chair of the Siberian branch's Commission on Nature Protection, informing Krylov that the Presidium of MOIP had authorized an on-site visit to the lake by a member of its Section on Nature Protection and sought the Siberian Commission's help in getting the MOIP representative in contact with nauchnaia obshchestvennost' in Irkutsk and in the Buriat ASSR. An urgent response, by air mail, was requested.[42]

As the start-up date for the Baikal factories approached, MOIP reasserted its central role as the voice of scientific public opinion. A chiding letter went to USSR minister of agriculture Vladimir Vladimirovich Matskevich in January of 1966 over the signatures of Varsonof'eva and Prozorovskii. Reminding Matskevich that within his ministry was lodged the Main Administration for the Protection of Nature (the direct descendant of Makarov's and then Malinovskii's Main Zapovednik Administration), the MOIP officials wrote that "we consider it our duty to bring to your attention the views of scientific public opinion concerning the problem of Baikal, as the situation, which continues to evolve thanks to the 'projects' of Giprobum, threatens with its consequences both the population and the survival of huge productive territories on land and in water that could be lost to the country."[43]

Every step of the project was based on bad science, argued the authors, from a lack of guarantee that the plant could actually produce a pure polymer needed for the viscose cord, to logging plans, and finally to pollution controls. Not wanting to indict the Party or the system of governance, however, Varsonof'eva and Prozorovskii blamed a six-year campaign of deceit by Giprobum, with the collusion of radio and the press, intended to mislead the public and the government. Consequently, they noted, the conclusions about the "project" reflected in the decrees of the Supreme Council of the National Economy of the USSR of July 27 and September 20, 1965 were also in error, reflecting a "contempt for the law" and an exercise of "arbitrary power."[44] Those decrees "did not accord with the opinion and recommendations prepared for the Supreme Council . . . by specialists and scientists who worked on that precise problem," complained the letter's authors. "In other words," they continued, "the leaders of the Supreme Council . . . proceeded undemocratically and at the same time demonstrated their lack of competence [emphasis added]."[45] Here again, we see the idea that decisive expert input into policy-making was congruent with "democracy" in

the understanding of the high scientific intelligentsia, which continued to hold to the "Progressive era" notion that political problems such as the "appropriate" use of natural resources could be resolved by scientific experts.

"The USSR Supreme Council of the Economy by its two decrees considered it possible to offer the natural wealth of Baikal up to adventurers for the conduct of criminal experiments," Varsonof'eva and Prozorovskii continued, reflecting the old-line scientists' visceral revulsion against Soviet "transformism." Like acclimatization, Baikal became a symbol of officialdom's desire to turn the entire Soviet Union—nature and people—into a guinea pig for its ignorant and short-sighted experiments. And like the zapovedniki , the lake was regarded as one of those rare places that had somehow miraculously retained its pristine qualities despite the system's thirty-year military-style campaign.

The MOIP letter aspired to discredit those whom natural scientists viewed as compromised "specialists," reserving for natural scientists the right to represent both science and society. Some geographers and especially economists "for some reason are unable to break out of their bureaucratic agencyminded narrowness" to recognize the greater truth spoken by natural scientists, the MOIP officials explained, and demanded that the authorities heed "the opinion of scientific organizations representing more than 20,000 scientists and specialists, as well as that of the All-Russian Society for the Protection of Nature, which embraces broad masses of progressive Soviet public opinion."[46] They attached nineteen pages of resolutions adopted by nauchnaia obshchestvennost' that demanded solving the problem of Baikal "in accordance with the scientific and moral bases of our epoch," which the Giprobum proposals decidedly did not do.[47]

With the exception of a few regime collaborators like organic chemist N. M. Zhavoronkov, secretary of the Chemistry Division of the Academy, who chaired a committee that gave its stamp of approval to the factories, much of the scientific and literary establishments, following the lead of their respective activists, strongly opposed the projects. A collective letter to Komsomol'skaia pravda of May 11, 1966, "Baikal Waits," signed by Academy vice president B. P. Konstantinov, academicians L. A. Artsimovich (physics), A. I. Berg (cybernetics), B. E. Bykhovskii (zoology), I. P. Gerasimov (geography), Ia. B. Zel'dovich (physics), P. L. Kapitsa (physics), G. V. Nikol'skii (zoology), V. N. Sukachëv (botany), and A. A. Trofimuk (geology) among other full members of the Academy, plus scientists Galazii and Zenkevich, Old Bolshevik F. N. Petrov, writers Chivilikhin and Leonid M. Leonov, MOIP Baikal Commission chair Prozorovskii, actors, and others, embodied this unusual coalition. Terming the decision to build the plants a "mistake" by the Gosplan USSR Committee, the letter described the decision-makers as having "taken a risk of unheard-of scale, turning Lake Baikal into an experimental

basin for the trials of a pollution abatement system that has never been tested in actual production conditions and which is not suited to the severe climatic conditions of the Transbaikal region."[48] "Those who created and encouraged the realization of these virulent projects should pay for their vulgar errors and oversights, for their arrogance toward the voice of Soviet scientific public opinion and for the suppression of criticism," the letter boldly demanded; "it is intolerable that the whole country pay for their mistakes."[49]

In its editorial commentary on the letter, Komsomol'skaia pravda asked, "Have we really learned nothing from the countless examples when economic bureaucrats in the name of the plan devastated waterways and lakes and poisoned their currents?"[50] "Readers may well ask: What the heck is going on?" the editors continued. "Why have the powerful voices of protest and the well-argued positions of science remained only a matter of conscience for an alarmed public opinion?" Even Gosplan's new commission, headed by chemist N. M. Zhavoronkov, reported the editors, showed no hint of taking the concerns of science and society seriously. "Comrade Zhavoronkov categorically refused to comment now in any form on the work of the commission in advance of a final decision," reported the editors, who explained that they had tried to elicit his views. To the editors the style of Zhavoronkov's treatment of the press and public opinion now became important in its own right. "This calls forth a sense of shock," they wrote. "Why is an agency whose decision is awaited by thousands conducting its activities in such a secret atmosphere?! Perhaps it is the case that the conclusions of the commission will follow a fait accompli, and the problem of construction on Baikal will be decided without prior consultation."[51]

Meanwhile, MOIP set about organizing a more public protest, reminiscent of the "three societies" meetings of the 1950s. A big scientific conference, "The Future of Baikal," was convened on June 13, 1966 at the Moscow House of Scholars. In advance of the meeting MOIP scholarly secretary Nikolai S. Dorovatovskii wrote to N. N. Mesiatsev, chair of the USSR Council of Minister's Committee on Radio and Television, asking that the radio station "Iunost"' be allowed to tape the speeches and musical intermissions for rebroadcast.[52] Expectations of a major event were justified. Once again, the aristocratic mansion was filled with the energy of an aroused scientific intelligentsia. Officially, 618 attended, rivaling the mass convocations of 1957 and 1958.[53] Judging by the resolutions adopted, the atmosphere at the conference was militant.[54] The collective letter to Komsomol'skaia pravda probably played a role in encouraging the large turnout and the belligerent stance.

Immediately after the conference Prozorovskii was again sent to Baikal, and on July 5 letters were sent to Brezhnev, Kosygin, and Podgornyi addressing them not as "General Secretary," "Chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers," and "Chairman of the USSR Supreme Soviet," respectively, but

simply as "Deputy to the USSR Supreme Soviet" (as they were referred to in the conference resolutions), with a conspicuous lack of deference.[55] The letter accused the new plants of "violating the basic principles of proper resource use" and of "leading . . . to the loss of Baikal and its adjacent alpine region." The MOIP letter was uncompromising in its opposition to the plants. Referring to a recently proposed technological fix, Varsonof'eva and her colleagues wrote that "these mistakes cannot be remedied, even by means of building a pipeline from the outflow point of one of the factories to the Irkut river," which did not flow into the Baikal basin. "Only dismantling both cellulose plants and relocating them outside of the Baikal basin can rectify these dangerous mistakes," concluded the letter, citing a resolution to that effect supported by the mass meeting of scientists.[56]

One of the last letters sent by V. N. Sukachëv in his capacity as president of MOIP, cosigned by vice president A. L. Ianshin and by Prozorovskii, was to Viktor Borisovich Sochava, director of the Institute of Geography of Siberia and the Far East.[57] The aim of the letter was to galvanize geographers to more active opposition to the development of Baikal. Reiterating the point made by the 1964 article in Oktiabr' , Sukachëv and his coauthors noted that since the 1958 conference on productive forces of Siberia "about forty meetings, symposia, conferences, gatherings, and congresses of scientific public opinion in our country—embracing about 20,000 scientists—have . . . expressed a negative assessment of the scientific basis of the project of Giprobum." Added to these was the disapproval of the project by VOOP, with its ten million members, and the applause elicited by the author Mikhail A. Sholokhov when he criticized the project at the Twenty-third Party Congress in 1966. Further, materials from the Conference on Soil Erosion in the Buriat ASSR, held in 1963, already testified to the serious problem of deforestation in Eastern Siberia and its associated problem of soil erosion.[58]

Invoking a moral imperative, the letter argued that scientists did not have the right to condone catastrophic mistakes simply because they were only following orders:

It would be a mistake to think that the state can remove the responsibility of a scientist for mistakes of bureaucratic projects and their consequences, for the potentially tragic fate of Baikal. On the contrary, we hold that at present, when the fate of Baikal is subject to the whim of the wrong people and the wrong institutions, . . . the responsibility of scientists has correspondingly increased. . . . We are inclined to support a course of action where scientific public opinion, independent of bureaucratic strictures, should get the Academy of Sciences system to adopt its set of recommendations for solving the problem of Baikal . . . taking into account the views of scientific public opinion.[59]

Sukachëv and his colleagues specifically asked for Sochava's support in passing a resolution at the Conference of Geographers of Siberia and the Far

East, scheduled for September 23, 1966, and for a discussion within the Geographical Society of the USSR.

This first full-scale coalition of the scientific intelligentsia and Soviet writers (the division between liriki and tekhniki does not reflect the significantly more complicated social identities of the educated stratum), including the reform press, gave no quarter to the "planners." Nearly simultaneously with the great MOIP conference of June 1966, Komsomol'skaia pravda published a follow-up to the collective letter of scientists and writers. "A mound of responses to this letter lies here on the editor's desk," wrote the editorial commentary, and "the voice of the letters to the editor is unanimous—we must head off the catastrophe threatening Baikal as quickly as possible." Letter writers, we are told, criticized the Ministry of Forest, Pulp and Paper, and Woodworking Industries of the USSR, "which even now, after the protest in the newspaper, after the alarm expressed by broad scientific public opinion, continues to insist on going ahead with the construction . . . at Baikal."[60] Even the Economic Commission of the Soviet of Nationalities of the USSR Supreme Soviet, not to mention USSR Gosplan's own Council for the Study of Productive Forces report recommended relocating the cardboard plant being constructed in Selenginsk to another region, with the Economic Commission also endorsing a total ban on wastewater discharge by the Baikal plant into the lake (and its transfer by pipe to the Irkut River, which flowed into another basin).[61] The newspaper editors concluded the piece by insisting that the authorities take into account the letters received, that is, public opinion, as well as the scientific conclusions advanced by the authors of "Baikal Waits."[62]

On June 22, the venerable physicist Pëtr L. Kapitsa spoke at ajoint meeting of the Collegium of Gosplan of the USSR, the Collegium of the USSR Council of Ministers' State Committee for Science and Technology, and the Presidium of the USSR Academy of Sciences. To make his point, Kapitsa recalled an earlier American debate of the mid-1950s about atmospheric pollution by radioactive isotopes. Then, as now, he noted, there were two sides to the debate. One side was exemplified by the physicist Edward Teller. That group believed that atmospheric atomic testing would add only a small increment to existing ambient radioactivity. "They tried to prove their beliefs, of course, with long calculations" designed to demonstrate that the demands of public opinion to stop the tests were baseless, "which served a certain group of militarists and businessmen in the USA."[63] On the other side were scientists like Linus Pauling who held that "a formal, quantitative approach such as Teller's was not applicable in this instance . . . because we need to take into account the influence of these pollutants on the mechanism of biological functions." Sounding like Formozov or Geptner, Kapitsa asserted that

in nature there exist very precisely established biological equilibria whose mechanisms contemporary science does not yet know. But we do know that comparatively small factors can destroy this equilibrium and that then the consequences are capable of assuming a catastrophic scale. For that reason Pauling believed that even a small change in the nature of atmospheric pollution by radioactive elements cold . . . elicit substantially large changes in living nature and even fatal consequences for humans. Life has shown that Pauling was right.

Kapitsa found Zhavoronkov's expert commission similar to the virulently anti-Soviet Teller in its approach to risk and the value of life.[64]

The theoretical physicist's remarks also took a swipe at the pride of Soviet educational policy: the engineers. Doubtless, Kapitsa's view was colored by his elite disdain for the vydvizhentsy (social upstarts) who represented the great majority of the engineers and technicians as well as the nomenklatura bureaucrats of the postwar USSR. "From the debate the extremely low level of engineering and technical culture among workers of our paper industry has become painfully obvious. One example that shocked me was a statement by a worker in the paper industry during a consideration of . . . the question of the essential level of water purity for discharges from the cellulose plant." Kapitsa related that the official had annouced that there should not be more than 0.5 milligrams of silicon per liter of water. When the official was asked how he arrived at that figure, he responded that that was the figure offered by the foreign firm supplying the equipment.[65]

This extraordinary and vociferous protest ultimately failed. In 1966 the Baikal'sk plant started up, and the Selenginsk plant was running by the following year. The concerted protests of scientific and literary public opinion had failed to stop the plants, to force them to delay production until all pollution abatement facilities were running optimally, or, as had been proposed by some members of the Academy of Sciences, to divert the wastes by a long pipeline to the basin of the Irkut River, where they would flow into the Arctic Ocean rather than into the lake.

The story of the continuing opposition by Siberian scientists to the operation of the Baikal mills has been admirably chronicled by Josephson. The later unsuccessful attempts by various Academy of Sciences commissions—under I. P. Gerasimov, a geographer, and Vladimir Evgen'evich Sokolov, a zoologist—to compel the regime to revisit the issue have been sketched by a number of scholars.[66] In all likelihood for Sokolov, whose strengths were in administration and not scholarship, and perhaps also for Gerasimov, involvement in these high-profile commissions was a means of enhancing their standing both internally and abroad. Fighting for nature made one a hero. Certainly for Sokolov, who was a member of the Academy Presidium for many years, his strong stand on Baikal, his nature protection advocacy

generally, and the use of his personal influence to protect active researchers and activists within his Institute for Ecology and Evolutionary Morphology, were a kind of currency that purchased acceptance by more reputable scholars; they treated him with outward respect and appreciation in exchange for his political support and protection. This bargain may have soothed science bosses who obtained their high positions through nepotism but still suffered from bad consciences.

Did all of this clamor produce any tangible results for Baikal? After decades of decrees, resolutions, and calls for a "general plan," experts remain skeptical of their efficacy. The USSR Academy of Sciences cautioned in 1977 that Baikal was facing irreversible degradation. No one knows precisely the tolerances of the lake's myriad life forms for toxic effluents, thermal changes, and changes in dissolved oxygen and other gases. As Pryde has noted, in addition to the two big cellulose plants, "a hundred smaller enterprises around the lake still discharge untreated effluent. Thus, the lake's fate appears to remain undecided."[67] Pryde is being cautious in his judgment, but it is hard to find any experts who are optimistic about the future of the lake's biota.

For the dynastic intelligentsia, Baikal was another metaphor for the ability of rude, ignorant bureaucrats and their slightly less tainted engineers and technical advisers to usurp power and scientific credibility and to impose their devastating transformist experiments on society and nature. Some men and women of letters identified with the old-fashioned, scientific intelligentsia led by the field biologists, which now had attracted to its cause a significant number of theoretical physicists such as Kapitsa and other powerful intellects.

However, a discernible and increasing number of writers—also involved in the struggle to save Baikal—saw in the lake's ordeal a somewhat different story of Russia's purity threatened. In some cases, notably that of Sergei Pavlovich Zalygin, they melded various narratives to make new combinations. That nature protection issues could have such resonance testified to their evocative power in a modernizing society, on the one hand, and to the special status they enjoyed as a "protected" area of dissent in the neo-Stalinist state, on the other.