Chapter Nine—

VOOP after Stalin:

Survival and Decay

In their efforts to engineer a merger with the Green Plantings Society, the new leaders of VOOP were still employing the politics of protective coloration. Stalin's "Plan for the Great Transformation of Nature" was still a watchword in June 1953, and the Society sought to link itself to a political agenda endorsed by the state power. However, protective coloration was a strategy fraught with peril for the integrity of a social movement. It required a convincing outward display of loyalty in some key areas so that a certain internal freedom as well as political freedom of action could be maintained in other areas. It required that the movement project the appearance of a group of quaint, even slightly irrelevant (from a utilitarian Soviet perspective) old-line scientists, more interested in discussing questions of faunal distribution than challenging economic or political decisions, while it quietly defended and expanded its "state within a state"—the zapovedniki —or took aim at select individual policies. Such a strategy was effective enough during times of "normal" Stalinism, but even its greatest practitioner, Makarov, had been powerless in the climate of terror of Stalin's last years. If it took a mastermind such as the late Makarov to make protective coloration work in the best of times, what could be expected of his far less gifted successors? Under Avetisian, the strategy inexorably began to overwhelm what it was supposed to protect.

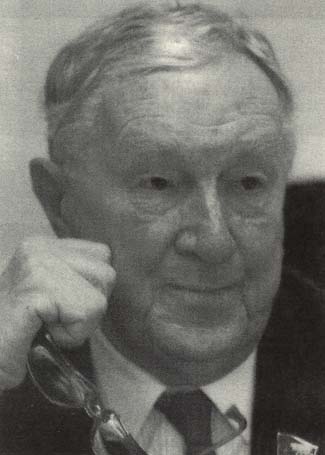

Gurgen Artashesovich Avetisian's (see figure 10) finest hour was bracketed by his valiant defense of VOOP as the lone dissenting voice on the RSFSR Gosplan Commission of 1952, on the one hand, and the triumphant convocation of the "three societies" zapovednik conference of May 1954, on the

Figure 10.

Gurgen Artashesovich Avetisian (1905–1984).

other. The influx of pragmatic planters, foresters, and horticulturists into the reorganized VOOP through its merger with the Green Plantings Society, combined with closer monitoring of the Society's activities by the RSFSR Council of Ministers, however, created the preconditions for major shifts in the Society's direction and operations. In an ominous departure from the Society's traditions, even Avetisian himself began to behave in a highhanded manner.[1]

The period 1953–1955 was an interregnum for VOOP as well as for Soviet society as a whole. In contrast to the thrust of the liberalizing changes in Soviet society, however, the interregnum in VOOP ultimately led to the

suppression of the autonomous ethos of scientific public opinion within the Society and to its takeover by corrupt Communist time-servers. This new period posed an even greater challenge to the old-timers. Indications mounted that the old traditions were being supplanted by a new approach to doing business. Lush, secretive bureaucratization quickly created a barrier between the new bosses and the old stalwarts. Emblematic of these developments was the way that the All-Union Congress of VOOP was convened in August 1955.

After long delays, a decree of September 5, 1954 of the RSFSR Council of Ministers marked the official inauguration of the new All-Russian Society for the Promotion of the Protection of Nature and the Greening of Population Centers, VOSOPiONP (although I will continue to refer to the Society as VOOP, to which name it reverted in 1959) The old Organizing Committee, composed of members elected to the Presidium of VOOP in 1947 and to the Presidium of the Green Plantings Society in 195 , was replaced by a lean new committee of seven: Avetisian, Dement'ev, Motovilov, Krivoshapov, V. I. Egorov, an agronomist, A. N. Volkov, and N. B. Golovenkov.[2] A new charter was prepared under the guidance of Avetisian, who remained chair of the Society's Organizing Committee pending the convocation of the founding Congress, set for 1955. In the meantime the Society hobbled along in a state of organizational limbo. Eight years had passed since the previous Congress, and VOOP was in severe violation of its charter. The Society had repeatedly petitioned the Party for permission to hold a Congress, which was repeatedly denied. This then served as fodder for Party accusations that the Society was delinquent in upholding its charter provisions.

On June 20, 1955, the Organizing Committee met at last to set the agenda for the Congress, which needed to be submitted not only to the RSFSR Council of Ministers but to the Central Committee of the Party as well. Although activists had proposed focusing on two questions, the ratification of the charter and elections of an official leadership, the Central Committee, which had been consulted beforehand this time, recommended adding speeches concerning fundamental principles and positions that would guide the Society's work. This delicate task was entrusted to the Party group within the Organizing Committee. Reports and talks were provisionally scheduled from Tsitsin, Formozov, Kozhin, the botanist Bazilevskaia, and Egorov.[3]

On July 29 the Organizing Committee finally got word that six days earlier, the RSFSR Council of Ministers had been given permission by the Party to allow VOOP to convene its first conference. At the new campus of Moscow State University on Lenin Hills the government had set aside 100 dorm rooms for visiting delegates. The main event was to be held in the university club. After waiting for the better part of a decade to hold such a meeting, the nature protection activists were given a scant two weeks to get the word out and make their preparations.

Almost furtively, without publicity, the VOOP Congress was convened on August 15. The old-timers were not invited. One remarkable document illuminating the episode is a pained letter from Susanna Fridman, VOOP secretary from the Society's inception until 1947, to interim VOOP president Avetisian: "I was completely shocked by your totally accidental mention of the convocation of the Congress," she opened, charging that she most likely never would have heard about it at all were it not for her unrelated request for other information from Avetisian. Fridman was as much saddened as she was outraged by the slight: "We old veterans of the conservation cause have been waiting for some years now impatiently for just this Congress. We dreamed of meeting one more time, discussing many issues of concern to us, summing things up, and perhaps clasping each other's hands for one last time. Most important, we hoped to pass on our passionate commitment to conservation to the young generation."[4]

However, the Congress was called in mid-August, observed Fridman, exactly at the time when "all scientific researchers are on vacation or on expeditions." To Avetisian's excuse (in his letter to her) that it had been decided not to invite many activists so as to keep costs down, Fridman replied that it was wrong to have slighted veterans and even founders of the Society, many of whom would have paid their own way in any case. Fridman reminded Avetisian of her own decision to turn down a 1,000-ruble award from the Presidium for her work organizing the Society's archive, a decision motivated by her concern for the Society's rickety finances.

Now, five founding members found themselves "thrown overboard" after thirty years of passionate service to the cause. Fridman was especially concerned that her exclusion from the Society's Executive Council would deprive her of an indispensable credential in her continuing efforts to propagandize on behalf of conservation in the media and in society; understandably, she feared that she would be called on to explain why she was no longer a member of the Society's governing body. "Of course," she reproached Avetisian, "had the old guard been present at the Congress, none of this would have happened. Neither Smidovich nor Komarov nor Makarov would have allowed anything like this." On the contrary, they would have proposed that the five living founding members be granted lifetime honorary membership on the Executive Council.

The snubbing of Fridman and the old guard was cause for yet another disappointment. Urged on the previous year by Professor G. G. Bosse, Fridman was at work on a major history of conservation, support of which she had hoped the Congress would provide. She had counted on the official endorsement of VOOP, but now, "to her great sorrow and humiliation," she felt abandoned. Unbowed, she vowed that she and a group of veterans would continue the project, and implicitly raised the prospect of unflattering portrayals of such recent scandals as the Kuznetsov affair and the 1955

Congress. Further, Fridman promised to write to others returning from field trips to let them know of these developments.[5]

The 1955 Congress and Its Aftermath

Russian conservation history is awash in first Congresses. In 1929 there was the First All-Russian Congress of Nature Protection Activists and in 1933 the First All-Union Congress for the Protection of Nature in the USSR. In 1938 the First Congress of the All-Russian Society for Nature Protection (VOOP) was held. And on August 15–17, 1955, the First Congress of the All-Russian Society for the Promotion of Nature Protection and the Greening of Population Centers convened in Moscow. (In June 1995, I might add, the First Russian Congress for Nature Protection was held.)

With its 130 voting delegates and 201 guests, it was a decent-sized affair, overshadowing the intimate 1947 Congress with its fifty-three delegates. Yet, confirming Susanna Fridman's worst fears, its atmosphere was alien to all previous Congresses. Only three of the eleven members of the Presidium—Avetisian, Dement'ev, and Professor P. A. Polozhentsev of Voronezh—could be called old-timers; the recognizable hearts and souls of the movement—Varsonof'eva, Formozov, Geptner, Fridman, Nasimovich, Zablotskii, Protopopov, Gekker—were all absent. Their places were taken by gardeners, selectioners, and presidents of provincial chapters.

Making the keynote address was Nikolai Nikolaevich Bespalov, one of Puzanov's deputy premiers who now, it seemed, bore principal responsibility for the fate of the movement. Bespalov's remarks seemed to be a continuation of the generally supportive attitude of the Russian Federation leadership toward nature protection: "Our people rightfully demand not only comfortable and attractive housing but beautifully laid out parks and gardens, and residential quarters, streets, and courtyards luxuriating in greenery and flowers. . . . Thus far we have only a handful of cities and population centers that meet these demands," and despite the annual investment of 500,000,000 rubles in urban landscaping and greening, ultimate success would depend on mobilizing the army of citizen amateur gardeners and nature lovers.

That is why the Congress . . . is so important. We must hope that it will facilitate the transformation of nature protection and . . . greening into a truly mass movement. In this cause we must not limit ourselves to government decrees although they are, of course, necessary. Agitation and propaganda are of paramount importance, as is upbringing and explanatory work, particularly among youths and schoolchildren. This is one of the principal tasks of the Society. . . . [Despite the fact] that nature protection and greening have been engaged in here for a long time, we cannot describe the existing situation as

favorable. Rapacious attitudes toward nature and green plantings are not rarities at the present time. . . . We must say bluntly that the local soviets until now have paid little attention to nature protection and green plantings. Especially here is where citizens' organizations must mobilize the attention of the population. Citizens' oversight over the proper use of natural resources must occupy a great place in the work of the Society and its branches. . . . We should also recall that nature protection and greening pursue a variety of aims, not only economic but also cultural and esthetic.

Bespalov concluded by noting that eight years had passed since the 1947 Congress, during which time "the economic and cultural needs of the country had greatly increased." That, in turn, demanded "a decisive mobilization in the area of nature protection and greening, and, in particular, a mobilization of the work of the Society."[6]

The most arresting and disquieting moment came near the close of the gathering, when one of the few old-timers present, Professor Pëtr Artem'evich Polozhentsev of Voronezh, took the floor. "It is awkward to express [my] feelings and impressions," he reflected, at first talking around the subject. "I have in mind the absence at this Congress of the distinguished activist for the protection of nature Comrade Makarov, who has left us forever."[7] Echoing Susanna Fridman's letter to Avetisian, Polozhentsev now alluded to the other "absent presence" at the Congress—the living activists from among the generation of founders who were not in attendance. Polozhentsev's remarks revealed an incipient perception that an era in the life of the Society had ended and that VOOP, now VOSOPiONP, had fallen into the hands of "new people":

I wanted to recall the enthusiasts of nature protection, by force of whose efforts our society not only managed to survive but also to have the opportunity to convene this present Congress. Are those present here aware that our Society was on the brink of obliteration? It is with a feeling of gratitude that I now recognize the following comrades: [F. N.] Petrov, Avetisian, Dement'ev, Motovilov, Varsonof'eva, Bazilevskaia, Krivoshapov, Protopopov, and others. It is also necessary to name those comrades who, working in the [Society's] paid staff, also maintained their support, such as Golovenkov and others.

Polozhentsev made a point of thanking some of the "newer" defenders of VOOP—Avetisian, Dement'ev, Golovenkov—in recognition that political realities would never again permit the control of VOOP by the Society's founders. With those thanks came the tenuous hope that the Avetisians and Dement'evs would be able to hold the line against the Volkovs, Egorovs, Manteifel's, Malinovskiis, and other convinced or cynical transformers of nature. "There are those who are trying to accuse the Organizing Committee of poor preparation for the Congress," Polozhentsev concluded, in a final attempt to lend support to Avetisian. Implicitly he seemed to recognize that

the convocation on short notice, the unpropitious selection of the season in which to hold it, and the disturbing omissions of the founders may well have been out of Avetisian's hands, the decisions of a higher authority:

Many of the biggest defects of the Congress, though, were scarcely in the competence of the Organizing Committee. But [even so] our Congress is taking place in a marvelous building and those of us who traveled here [from afar] were able to find housing with no difficulty. And that is all the work of the Organizing Committee, . . . [work performed] particularly under those conditions, when our voice is barely heard by those who should be encouraging us in our work. [Instead], they should say "Thank you, comrades, for your love of nature, for your efforts to enrich and to beautify our Motherland."[8]

An indication of the new order within the Society was quickly revealed in the report of the Charter Editing Commission, headed by Vasilii Vasil'evich Prokof'ev of the "Znanie" society. Noting that there had been a number of suggestions for the best possible name of the new society, including "Society of Friends of Nature" and "Society for the Transformation of Nature," Prokof'ev explained that the name was already a moot point insofar as the RSFSR Council of Ministers insisted on the existing cumbersome formulation "because it believes that the Society must chiefly orient itself toward population centers." Their view, he continued, was that "the Society must not take upon itself broad responsibility for the fulfillment of governmental measures," perhaps an allusion to the former VOOP's energetic and autonomous initiatives in the creation of zapovedniki and in the enforcement of anti-poaching laws.[9]

With dues set at three rubles for full adult members and fifty kopecks for youths, the Congress completed its work by electing a new Central Council of thirty members through secret ballot. Of the core group of old-timers, only Krivoshapo, Polozhentsev, and Formozov, elected in his absence, were now represented, along with second-generation members Avetisian and Dement'ev. With a clear majority, the "new people" were in the driver's seat.[10]

The first session of the Society's newly elected Executive Committee, which met on August 19 at the conclusion of the Congress, is one of the defining moments in the history of the merged society. The presiding officer of the August 19 session was not a member of the movement at all, but the same N. N. Bespalov, a deputy prime minister of the RSFSR, who had given the keynote address at the Congress. That in itself was highly unusual at a meeting of a voluntary society with VOOP's traditions. Then, announcing the order of business, which was the election of the Society's new president and vice presidents, Bespalov let it be known that the Society's pretensions to autonomy were a thing of the past. "Having weighed the various possible candidates," Bespalov Solomonically pronounced, "we have inescapably decided to recommend as president of the Central Executive

Council of the Society G. P. Motovilov," the former USSR minister of forestry. The vote was unanimous.

Nikolai Vasil'evich Eliseev, a veterinarian and head of the Russian Federation's new Main Administration for Hunting and Zapovedniki , was unanimously elected first vice president. Aleksandr Nikolaevich Volkov, head of the Moscow Plant Protection Station and president of the Moscow oblast' branch of the Society, was elected as the other vice president. In this coronation of bureaucrats there was one small jarring note when Ivan Stepanovich Krivoshapov, one of the few old-timers left on the new council, proposed the candidacy of Nina Aleksandrovna Bazilevskaia instead of Volkov, offering that there should be at least one biologist on the Presidium. However, these were new times, and objections from the new claque of careerists forced a hasty withdrawal of the botanist's candidacy. Only Nikolai Borisovich Golovenkov, the scholarly secretary of the Society, was reelected.

Elections to the remaining five slots on the Presidium were similarly conducted under conditions of guided democracy. Avetisian was left on, presumably as a courtesy, and Krivoshapov, Tsitsin, and Dement'ev were named as well; their appointment gave the Presidium a veneer of legitimacy. The remaining choice was the hack Vasilii Ivanovich Egorov, deputy inspector of the RSFSR Ministry of Agriculture's Division of Gardens, Viticulture, Subtropical Crops, and Teas. However, this compromise did not please the extreme anti-academic utilitarian wing, which demanded expansion of the Presidium to include at least one representative of the urban greening group. Another compromise was struck; the Presidium was expanded by two, and the "greener" Aleksandr Filippovich Lukash was elected together with Professor Nikolai Ivanovich Kozhin, a representative of the fishing industry. Two Executive Council members abstained from the vote on Lukash, but they, too, were clearly out of step.[11]

As we seek to understand episodes like these in the absence of full archival documentation, we must always keep in mind the temper of the times. When the republics were faced with repeated assaults on their authority and raids on their portfolios of responsibilities, they tried to defend as much as they could. To a great extent this stance explains the patronage and solicitude of the Russian Republic's government toward the Russian conservation movement and the Russian zapovedniki when they fell under attack. Although far from liberal, the leadership of the RSFSR played a crucial role in protecting Russia's version of civil society from obliteration. That the RSFSR leadership was willing to defend VOOP in the first place no doubt had something to do with its perception of nature protection as a low-risk issue. It could take a stand, implicitly defending its sense of its own importance in the bargain, without the likelihood of being purged.

With Stalin's death, though, the pressure on the republics from the center eased. It was time to frame new compromises and to blunt the edges of

conflict. Patronage of even a remotely dissident conservation movement became counterproductive under the new conditions of rapprochement with Khrushchëv's team. Although the Russian Republic never gave up the goal of restoring its zapovedniki and even maintained a certain respect for the old-line elite biologists who had led the conservation movement, it could not allow them to remain in control of a growing organization such as VOOP. Elite biologists could work in subsidiary roles in the RSFSR's Main Administration for Hunting and Zapovedniki under politically reliable bureaucrats, but they would never again be allowed to occupy highly visible positions, which only attracted the near-fatal attention of the center to them and to their patrons in the republic's leadership.

The Lakoshchënkov Affair

History occasionally is the story of surprising reversals. Romanetskii, the police bureaucrat who participated centrally in the persecution of the conservation movement, emerged four years later as a naive idealist whose outrage at the Party's abuse of power in the environmental area led him to confront Khrushchëv himself. Another example of how one man's behavior evolved from craven denunciation under Stalin to outspoken resistance under Khrushchëv is the case of Vsevolod Georgievich Lakoshchënkov.

In 1950 Lakoshchënkov was one of several members of the Moscow oblast' branch of VOOP who signed a letter denouncing the Society's old guard for promoting corruption and stagnation. The charges were wildly exaggerated and distorted—part of a campaign to remove the independent-minded leadership of the Society and to replace it with a more pliant and loyal Stalinist cadre. Nonetheless, these tactics were partially successful, resulting in the forced resignation of Makarov in 1952 and the eventual takeover of VOOP by Party hacks between 1953 and 1956. Although they failed to eliminate the autonomous, oppositional conservation movement, which migrated to the protection of the Moscow Society of Naturalists, the Party loyalists inherited the expanding machinery of the conservation society.

Lakoshchënkov was a local activist whose star initially rose with the ouster of the Makarov group. Beginning in 1948 he had served on the Presidium and as secretary of the VOOP branch of the town of Perovo, a Moscow suburb. From January 1954 through December 1956 he was a member of the Auditing Commission of the Moscow Regional branch of VOOP, along with V. S. Iukhno, director of the Prioksko-Terrasnyi zapovednik and president of the Serpukhov branch, and I. P. Kosinets, secretary of the Leninskii regional branch.

The commission met in October 1954, but the extreme disorganization of the financial records moved the commission to declare that it could not

conduct a coherent audit. Although Moscow VOOP branch president A. N. Volkov and the branch's bookkeeper proposed that the commission return in April 1955, by which time the documents were to be put in order the commission resolved instead to conduct an immediate investigation into possible malfeasance.[12]

The scholarly secretary, S. V. Butygin, had been wearing not one hat, but five, dispersing credits, serving as cashier, and acting as bookkeeper and safekeeper besides. The cash transactions that crossed his desk bypassed the Society's bank account and were therefore never officially recorded. Chaos also reigned in other matters. No membership lists were kept by the regional branches. A close associate of Volkov's, one Korshunova, had been hired as bookkeeper; she simply sat in the office and took the work home to her husband, who was a bookkeeper.

All of this impropriety, Lakoshchënkov alleged in his letter to V. M. Molotov (now USSR minister of state control), was intentional. Preying on Butygin's weakness for alcohol and his illness, as well as his dedication to the Society, Volkov had put the scholarly secretary in an untenable position. Deprived of honest, skilled bookkeeping support staff, Butygin soon was over his head as he struggled to take over those functions in addition to his normal organizational ones. In order to balance the available cash with receipts Butygin at one point had pitched in 2,800 rubles of his own money.

Complications multiplied at a meeting of the VOOP Executive Council on November 12, 1954. Despite the absence of a report from the Auditing Commission, Volkov blamed the messy books on Butygin, whose removal he now demanded. He also demanded the exclusion from the council of P. P. Smolin for his "bungling" of "Bird Day," of M. G. Groshikov for "inactivity," and of P. A. Manteifel' on account of his overcommitted work calendar. Volkov's agenda was not simply to rout the old-line professors and field naturalists. He wanted the field cleared for an even more radical conversion of the Society. Volkov sought to remake VOOP into a profitable business.[13] True, the Society would promote a little greening here and there, but that was all beside the point. The point was profit, and that is why Volkov needed to retire even such personally honest philosophical supporters of the "transformation of nature" as Manteifel'.

As early as mid 1954 Volkov began to assemble his confederacy of wheeler-dealers. P. A. Petriaev was brought on board as scholarly secretary, with two contracts for 5,250 rubles total for "research" and an additional payment of 2,850 rubles for undocumented "lectures" on behalf of VOOP to sweeten the deal. Other Volkov allies, such as P. V. Tsibin, V. S. Iukhno, I. P. Kosinets, and Zemering, head of the Mytishchi regional branch, were also brought into the Presidium.

Commercial activity immediately assumed two lines of action. One was the purchase and resale of DDT for profit by the Moscow regional branch.

Apparently, no financial documents were kept of the transactions within the Society; information and documents bearing on the purchase did turn up in a search of other agencies' files. Nevertheless, testimony was received that the VOOP branch in Mytishchi sold the DDT at more than 200 percent of the average price. Perhaps more shocking was the second commercial operation, which got under way in October 1954. More than any other scandal, it exemplified the ethical rot that accompanied the ouster of the old-timers by the new group. Tsibin and Iukhno were the ringleaders in a scam to uproot 12,000 eight– to ten-year-old linden trees from the Prioksko-Terrasnyi zapovednik and resell them for huge sums to interested parties, including the Moscow Telephone Construction Trust. Not only were the trees being illegally pillaged, on the sly, from a nature reserve, but the operation was being masterminded by the reserve's own director, Viacheslav Stepanovich Iukhno.[14] Volkov and his people managed to combine Stalin and Lysenko's development philosophy with the moral vision of the Mafia.

Other unsavory characters were brought in to round out the commercial operation, which by 1955 involved the "sale" of 8,223 trees fetching hundreds of thousands of rubles.[15] Whereas the tree removals commenced in April 1955, official permission for the operation was retroactively provided in May and October by the Main Administration for Zapovedniki . Malinovskii himself signed on to the scam. On August 13, the Presidium of the Moscow branch of VOOP awarded V. S. Iukhno 1,000 rubles as a bonus for his successful commercial transaction.

Two more audits were held in 1955, the first conducted by Lakoshchënkov and the auditing bookkeeper, F. K. Alëkhin. Its results, published December 31, 1955, were described as "slanderous" by Volkov, deputy president V. K. Alekseev, and the other regional Presidium members. Then the Moscow oblast' Party Committee's Agricultural Sector ordered a second audit. Gagarin, deputy head of the sector, even went so far as to recommend that branch president Volkov not remain involved in the linden tree business, speaking at the Second Moscow oblast 'Conference of VOOP in 1956.[16] However, the composition of the auditing commission gave one pause; Iukhno, Alekseev, Kosinets, and Butorin (of the All-Union VOOP)—precisely those under the cloud of suspicion—formed its majority.[17] Seeking to explain Lakoshchënkov's absence from the commission, its members asserted that he "declined to serve, giving the excuse that he would be away on business . . . until April 12, 1956." According to Lakoshchënkov's own letter to Molotov, he refused to serve because of his strong objections to the participation of the officials responsible for the alleged abuses.

At the Second Moscow oblast' Conference of VOOP where the Party official warned regional VOOP leaders to abandon the tree sales, Lakoshchënkov and Alëkhin were expelled from the Moscow Regional branch of VOOP

"for slanderous activities within the Society."[18] The vote was a disheartening 146 to 2.[19]

Repeating essentially the same charges in a letter to Soviet premier Nikolai A. Bulganin written in early July 1957, Lakoshchënkov added an arresting note of emotionality to his appeal for vindication.[20] "You know perfectly well," it opened, "that there is a limit to the amount of pressure that a person can tolerate, and a limit to the social and personal sufferings that the heart is able to bear, especially the heart of a seventy-five-year-old man." Referring to his letter to Molotov, which he enclosed, Lakoshchënkov pointedly accused "the Communists A. N. Volkov. . . , V. K. Alekseev, and G. P. Motovilov, president of VOOP," of a massive cover-up, "denying everything" and "declaring war on all who criticized their improper actions." For Lakoshchënkov, the issue had now expanded from financial and resourcerelated abuses to the highly political question of Communists' abuses of power:

They are using their experience and their bureaucratic positions in their struggle against me. . . . Most troubling is that no one has stood up to their attempt to quash criticism. In their actions they, as Communists, have ceased to relate to [us] in a personal, individual, and human way; decency is a basic law of human culture. Are we not Soviet people, even if that fact is unpleasant for Volkov, Alekseev, and Motovilov? As such, we too have the right to a certain amount of respect and the right to defend our dignity. They just do not seem to understand that elementary rule, and, despite my appeals, no one else has yet pointed out their errors to them, either.[21]

The fate of Lakoshchënkov's appeals closely parallels those of other naive missives of the Khrushchëv and Brezhnev periods. Molotov himself probably never saw the first letter, which was forwarded by his Bureau of Complaints to G. P. Motovilov, president of VOOP. Maintaining the stonewalling, the May 15, 1957 reply drafted by VOOP secretary V. V. Strokov was scathingly dismissive and reaffirmed the decision of the Second Moscow oblast' Conference of VOOP of 1956 expelling Lakoshchënkov and three others for "defaming Communist citizen activists."[22]

Lakoshchënkov appealed to Molotov and Bulganin for reinstatement and declared his readiness to submit to a trial over whether his accusations constituted slander. Instead, a hearing was held by the Presidium of the national VOOP, now incensed that Lakoshchënkov would turn whistle-blower. In a confrontation with the N. V. Eliseev, vice president of VOOP and head of the RSFSR's Main Administration for Hunting and Zapovedniki , Lakoshchënkov reaffirmed his readiness for a slander trial. Eliseev rebuked Lakoshchënkov for turning to outsiders "with misinformation" instead of to the national Society's Executive Council; apparently, at Lakoshchënkov's prompting, reporters from Literaturnaia gazeta even called VOOP and asked why an old and

dedicated member of the Society was unjustly expelled and why his complaints were being shunted aside. It was all exceedingly embarrassing and nasty.

VOOP's vigilant trustees in the Russian Republic felt obliged to respond. On November 19, 1957, Motovilov and Eliseev were called in to the office of Deputy Premier Bespalov to discuss the fate of the Society. Although tightening trusteeship over the Society represented an additional burden for the Republic's leadership, no alternative was seen. Bespalov would take overall responsibility for VOOP himself, while an aide, Semikoz, of the Agricultural Section of the RSFSR Council of Ministers, would handle day-to-day affairs.[23]

With time, however, there was a broad "normalization" of the internal workings of the Society; nothing remotely resembling an internal critique against the new line was to be heard within VOOP, and the state trusteeship was lifted after a few months. For its part, the RSFSR was glad to get this responsibility off its hands. Nikita Khrushchëv was implementing his notorious plan to create putatively self-contained economic regions to replace the system of branch ministries, and the republics had few bureaucratic resources to spare for such low-priority items as voluntary societies. Accordingly, VOOP was now free to pursue its new agenda unhindered, or so it seemed. The lush bureaucratization and commercialization of VOOP swung into full gear. The Lakoshchënkov flap highlighted the degree to which VOOP had become unrecognizably different from what it had been only five years earlier.

1955–1960

Of all the indicators that a new ethos had taken hold in VOOP none was more vivid than the proliferation of a network of profit–oriented commercial outlets—the Priroda (Nature) stores. This chain of stores required a large amount of start-up capital from the parent society, as provincial conservation-entrepreneurs all tried to get in on the act. In July 1956, the Leningrad City branch of VOOP asked the central leadership for a loan of 100,000 rubles to be repaid by January 1, 1957. It was approved.[24]

Another emblem of the new approach was an indiscriminate campaign to recruit new members. This increasingly involved the induction of so-called "juridical members," entire factories or schools, for example, that joined as institutions. During the discussions of the budget for VOOP for the coming year at a Presidium meeting of January 19, 1956, Vice President Volkov proposed a cut in the publishing expenditures of the Society and a revved-up membership drive instead. Egorov, seconding this, proposed no less than

a 50 percent increase in membership, to 300,000.[25] President Motovilov concurred, adding only that the Society should further recruit 200,000 additional Young Naturalists, for a grand total of 500,000.

The new line also demanded leadership even more in tune with its bureaucratic-entrepreneurial goals. Only a year and a half after the imposition of a new leadership, Motovilov was complaining that, of all the Presidium members, only Volkov, Krivoshapov, and V. V. Strokov, the new secretary who replaced Golovenkov, were satisfactory.[26] Kozhin and Avetisian were denounced as ineffectual deadbeats, and they soon left the leadership.[27] The interregnum was over.

The Annual Report on VOOP Activities for 1957

In his presentation of the annual report, A. N. Volkov, deputy president, made the customary complaints about insufficient funds and organizational shortcomings. But internal factors were not the only impediments to the Society's meeting its goals. Despite the relatively small number of individuals involved, the defection of the old-timers to the Moscow Society of Naturalists (MOIP) posed a perceptible threat to VOOP's claim to represent nature protection.

Susanna Fridman, in a letter to Vera Varsonof'eva written late in 1958, again throws light on the deep wound this loss of a social "home" caused her and the old guard. Commenting on the departure of the "exiles," as she termed the old-timers, Fridman ventured that they should not have left so quietly: "It was absolutely necessary to have written an 'acerbic' letter to the new Presidium concerning our departure. . . . Our whole group should have signed such a letter; let the document remain as testimony in the Society's archives. It is too easy simply to beat a retreat. I would have typed up a letter and sent it to the newspapers."[28] Fridman also informed Varsonof'eva that she had saved an old postcard from Grigorii Aleksandrovich Kozhevnikov recommending her for membership in MOIP. In asking Varsonof'eva to admit her to membership, Fridman confessed that she "could not bring anything useful to the Society." Nevertheless, in her last months she only "wanted to be alongside you [Varsonof'eva] and Aleksandr Petrovich [Protopopov]."[29] Better evidence for the poignant place of their societies in the hearts and souls of nature protection activists would be hard to come by.

Although the defection of the Makarov-era activists was almost inevitable, given the changes in VOOP from 1952 on, Volkov had underestimated their mettle; it was difficult for hacks to grasp the intensity of the old-timers' commitment to their values and their capacity for autonomous organization.

"It is entirely incomprehensible to me," admitted Volkov, "how conservation work has been going recently. I don't like the intrusions of MOIP [into our area]," he continued.

The Moscow Society of Naturalists is a respected organization, but MOIP is convening a conference on zapovednik problems, has called a conference on conservation problems generally, that is, MOIP has gotten involved in those issues which are the province of our Society. And we are not concerning ourselves with those issues that we should concern ourselves with. [Conservation] is not the prerogative of MOIP, but a group of activists has appeared there and they are not performing badly.

At that point, a voice from the hall dared to state the obvious: "Those are our former activists!" "Right you are!" concurred Volkov, who added wistfully that "they are moving ahead while we are standing on the sidelines . . . not only not initiating [these conferences] but not even taking part." That left the field open to the elite biologists, who, "at these conferences, dump on us, as a Society, without compunction."[30]

Cleansed of nauchnaia obshchestvennost' , the Society now sought to rejoin the international conservation movement. This time, domestic obstacles were significantly reduced. Khrushchëv's foreign policy emphasized reintegrating the Soviet Union—in a managed way—into the world's economic and diplomatic systems. And the VOOP leadership was now composed exclusively of dependable Communists or those close to the Party. Accordingly, on August 11, 1958, the Presidium sent a memorandum to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) asking permission to join the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, which was affiliated with UNESCO, and to attend its conference in Athens and Delphi. Professor N. A. Gladkov of MGU, a Stalin Prize laureate, would represent the Society.[31] A delegation of three, headed by Gladkov, had attended the Twelfth International Ornithological Congress in Helsinki in March 1958.[32]

The new leadership had put particular emphasis on building membership. By 1958 membership was up to 242,624, an increase over the previous year of 100,000; still, it included only 80,261 adults.[33] In response a number of strategies were advanced. One emphasis was to attract more juridical members, which now numbered 1,106: another was to lure individual members with contests and prizes.[34]

By 1959, when the Society's Second Congress convened in Moscow, one year late, membership had swelled to 916,000.[35] The staffs (including both the center and the affiliates) had grown commensurately from 24 paid staffers in 1956 to 306 in 1959, and consisted of bookkeepers, scholarly secretaries, clerks, typists, and instructors/lecturers.[36] If disbursements, including staff salaries, climbed in this four-year period, income also rose, from

1,559,500 rubles in 1956 to 3,584,900 in the first nine months of 1959.[37] Of this, membership dues accounted for only 245,294 rubles, or 7 percent of all income. Despite this impressive growth, it was calculated that to break even the Society would need 9 million members (3 million adults and 6 million youths); even the lucrative Priroda stores and the postcard, album, and literature sales could not generate enough profit to keep the operation growing.[38]

A breakdown of the delegates by age, length of membership in the Society, education, and Party membership told the story of the restructuring of VOOP. Of the 316 voting delegates, plus 37 with consultatory status who attended, three-quarters were Party members (243), Komsomols (8), or Pioneers, with only 101 non-Party delegates. The loss of the old guard was even more dramatically highlighted in the tiny number (14) of scientists with degrees of kandidat nauki or higher or with the title of professor. Finally, those who had been in VOOP prior to 1954, when it merged with the Green Plantings Society, constituted less than 25 percent of the delegation (81 in all).[39]

Much of the discussion at the Congress, therefore, was tame or even trite. There was much talk of gardening techniques, which pesticide to use on orchards, new hybrid flower varieties, and other horticultural issues. Some of the livelier moments concerned how to make VOOP a financially viable operation. Nature protection was almost an afterthought. Nevertheless, a few voices still reminded the Society of its ostensible mission. One of them was that of Vera Aleksandrovna Varsonof'eva (see figure 11), one of the Society's oldest members and vice president of the "competition," the Moscow Society of Naturalists (MOIP).

As one who "began working in the Society . . . in the first years of Soviet power," Varsonof'eva sought to claim Lenin's endorsement for a stouthearted stance for nature protection. "V. I. Lenin understood well," she asserted, "that with the development of the young socialist state a colossal exploitation of natural resources would be required," but he also knew that "for proper exploitation it was essential to understand all the complicated interrelationships that exist among elements of the landscape. . . . On this realization was based that grand scientific program . . . that was pursued in the zapovedniki . VOOP, in its original form, participated broadly in the scientific work." she continued, in an implicit rebuke to the new direction of the Society.[40]

However, now was hardly the time to slacken one's vigilance. She noted that in ten years almost 21 percent of the Carpathian forests of Ukraine had been cut, and the woodlands would last only another ten to fifteen years at that pace. In Siberia, the Siberian stone pine (Pinus sibirica-kedr, or "cedar," in the Russian vernacular) was disappearing, while pollution was engulfing more and more formerly pristine rivers and lakes, such as the Chusovaia

Figure 11.

Vera Aleksandrovna Varsonof'eva (1889–1976) .

Vladimir Nikolaevich Sukachëv (1880–1967) is seated at right.

River in the Urals. Part of the problem was that planners and bureaucrats failed to consult with scientists, and the results were not only pollution but disastrous agronomic-engineering schemes such as that which was leading to the desiccation of Lake Sevan. "One would think," she remonstrated, "that the Conservation Society would put precisely this kind of problem at the top of its list of priorities. For this reason it is wrong to view the two questions—of nature protection and of urban greening—as equally pressing. The question of urban greening is linked with that of human health and it is doubtless important." However "it is ill-considered to view it as equal in importance to the urgent and great problem of nature protection."[41]

Varsonofeva explained that preserving nature's "untouched baseline territories" was not for the sake of an abstract Nature but for living people, and not simply for material well-being but for a more transcendent aspect of human existence: the "restoration of the moral forces of the human being." "We must preserve standards [etalony ] of the beautiful age-old nature of our Motherland," she continued, "and there, where life forces us to alter its visage, we must not leave a defaced, deformed wasteland. We must pass on to our descendants monuments of nature in their original beauty. . . . The most urgent task of our society is—the protection of nature."[42]

A Leningrad delegate, Georgii Ivanovich Rodionenko, was more direct:

I would like to pose the following question to the members of the Central Council. Have they raised even one problem of national scope, such as the fate of Lakes Sevan or Baikal or of a large zapovednik ? Nothing was uttered about these problems either in the [official] report or in the other announcements. It seems to me that we must elect to the new Central Council, in addition to those who are adept at organizational work, specialists with a broad field of vision. Without their help it will be difficult to raise questions having national import.[43]

One speaker, V. V. Tarchevskii, a delegate from Sverdlovsk oblast' , raised the relatively new problem of air pollution. Cheliabinsk made the problem not only visible but inescapable. "Over all the cities in Sverdlovsk oblast' ," said the delegate, "and there are 101 of them, lie permanent clouds of smoke. The atmosphere is polluted with toxic wastes dangerous to human beings. For this reason the question of the protection of individual elements of nature, especially the atmosphere, is extremely urgent."[44] Painting a ghastly picture of cities in the Urals surrounded by "deserts of life . . . for dozens of kilometers out from the city perimeters, where there is no vegetation," Tarchevskii complained that already in the oblast 's third largest city, Kamensk-Ural'skii, "it is impossible to breathe" owing to the waste belched forth from the monster Urals Aluminum Smelting Plant. He described clouds of asbestos and enormous, exposed waste dumps in the city of Asbest. The oblast ' branch of VOOP sought to plant them over, but what was really required was a massive national campaign to rehabilitate mined-out and degraded land and, especially, to clean the air.[45]

Another delegate, from Astrakhan', informed the Congress about bacterially contaminated rivers of her oblast ' and the writers Oleg Pisarzhevskii and E. N. Permitin cautioned that socialism ipso facto did not guarantee "safe" industrial working conditions.[46]

Despite these few brave words, the activities of the Congress displayed a monumental complacency, reflected in the election of the new president and Presidium. The Russian Republic minister of forestry, Mikhail Mikhailovich Bochkarëv, was selected to lead the Society for the next three years, while the politically reliable Andrei Grigor'evich Bannikov, a mediocre zoologist but regime loyalist, was elected first vice president. Nikolai Vasil'evich Eliseev was named, more or less ex officio, as was past president Motovilov. The only pre-1955 faces were those of Avetisian and Gladkov, who were unlikely to oppose the further commercialization of the Society.

The archive contains Vera Varsonof'eva's secret written ballot for the Central Council of the Society. Fifty-five names were listed as candidates for the Council and fifty-five individuals were ultimately elected to that body. But

Varsonof'eva only placed approving check marks next to twelve, not counting herself—the only real old-timers. Indeed, the only Presidium members she considered voting for were Gladkov and Avetisian.[47]

A few of the Society's publications did address some of the major issues of environmental ruin. An article in the Society's journal Okhrana prirody i ozelenenie (Nature Protection and Greening ) was remarkably candid about the extent and location of water pollution in the USSR and even identified some point sources with descriptions and amounts of their effluents.[48] A much more extensive brochure, authored by the botanist G. G. Bosse and the population geneticist and ecologist Aleksei Vladimirovich Iablokov and designed to coach the Society's lecturers, underscored the problems of biotic conservation that were largely ignored at the conference while also defending the aesthetic side of nature protection as an expression of patriotism.[49] However, these were the rare exceptions to the flood of pamphlets about gladiolus varieties, ornamental trees, and new pesticides for apple orchards.

Although politically, morally, and intellectually stagnant, the Society grew like topsy. By 1962 its membership had ballooned to nine million. VOOP—in 1959 it had regained its old name—had not only become the largest nature protection society in the world, but also one of the largest non-state businesses in the Soviet Union.

Chapter Ten—

Resurrection

A highly unusual conference on the nature reserves was convened in the spring of 1954 by three voluntary societies, MOIP, VOOP, and the Moscow branch of the Geographical Society of the USSR (MGO). The zapovednik conference is a watershed in the history of the Russian and Soviet conservation movements for a number of reasons. First, with almost geological force it thrust up the seething, formerly self-censored passions of the scientific intelligentsia to the surface of public life: its anger, its sense of wounded dignity, its unrelenting claim to a decisive role in public policy, its bitterness at the expropriation of "its" archipelago of freedom—the zapovedniki , its disdain of the values and utilities of the Stalinist bureaucracy, and its unrequited patriotism.

Second, the conference ushered in a period of ascendancy in the movement's history of the Moscow Society of Naturalists and the Moscow branch of the Geographical Society, and with it, a new, highly visible place for geographers and geologists. This occurred against a backdrop of chaos and a leadership interregnum in VOOP, so recently rocked by financial difficulties, dissension, regime persecution, and Makarov's retirement and death.

Third, even while the majority of the old activists were still determined to restore the status quo ante and hence equated nature protection with the zapovedniki , new voices were heard at the conference and new concerns were tentatively expressed that prefigured a broader agenda for the movement: the issues of pollution and of resource management outside the reserves system.

Malinovskii's new Main Administration quickly began to reorient the scientific work in the rump zapovednik system. The main orientation became

developing means of "increasing" nature's productivity. For example, at the Voronezh reserve, work intensified on replacing the "unproductive" aspen forest with other tree species.[1]

Of the total area of 1,328,700 hectares that remained in the twenty-eight reserves of Malinovskii's system, twenty-three reserves with an aggregate area of 915,600 hectares contained forests, of which actual forest cover accounted for 67 1,500 hectares. Of these, 58 percent were characterized by Malinovskii as very mature or old-growth and another 13 percent as mature.[2] Although forestry measures in twelve of the twenty-three forested reserves were limited to fire control and anti-poaching measures, in the other eleven, some of which were still quite large, "forestry measures . . . were being conducted in full measure."[3] "Full measure" included such "biotechnical means" as clearing trees from the enclosed bison range in the Belovezhskaia pushcha in order to plant new forest browse, or clearing black elm in the floodplain of the Usman' River, which had been impeding the growth of willows, the tree of choice for the local beaver.[4] Malinovskii's vision of the role and function of zapovedniki mirrored that of the Stalinist theorists of the 1930s—Arkhipov, Boitsov, Veitsman—who saw the reserves as experimental areas to create the lush, superproductive "Communist" nature of the future.[5]

Biotechnics

"Biotechnics," the technical means to achieve a "reconstruction" of "first nature," embraced an array of disparate measures: predator control, pesticide application, the introduction/acclimatization of exotic species of plants and animals, supplementary feeding and the provision of salt licks, and the removal of existing vegetation in favor of another species mix. Motivated by a single-mindedly economic yardstick of benefit, measured in currently identified resources, this reconstruction of nature was also wedded to a voluntaristic perception of existing nature as backward, unplanned, and not having reached its productive potential. Soviet biotechnics would correct all that.

Ever since the first epic battles over acclimatization, especially those fought at the 1929 and 1933 nature protection congresses, biotechnics had acquired intense symbolic meaning for the two opposing sides. This was particularly the case regarding proposals to carry out acclimatization and other biotechnical measures in the zapovedniki . For the Stalinist nature-transformation enthusiasts, these measures were weapons in their war against the prerevolutionary, indeed counterrevolutionary, inertia of old Russia. No community—neither human nor ecological—would be permitted to stand aloof from the complete refashioning of one sixth of the earth's surface into a

gleaming, rationally planned socialist commune. Nothing would be allowed to "go its own way."

For the nature protection activists acclimatization meant much the same thing, but the proposed "great transformation" elicited not enthusiasm but horror, disdain, and ultimately resistance. Acclimatization, especially in zapovedniki , threatened the last little islands of "inviolability," beauty, and purity in the swirling and profane sea of Stalinist changes. True, the threat was ecological—portending the spread of parasites and the transformation of acclimatized species into pests and public menaces. But it was also symbolic, marking the intrusion of the Party-state and its machinery into the last holdout of the scientific intelligentsia. It was a struggle over whether there was to be any kind of "geography of hope" in the Soviet Union.

Makarov and Smidovich in the 1930s decided rhetorically to capitulate to the nature-transformers, renouncing the principle of the "inviolability of the zapovedniki " and admitting the permissibility in those reserves of "biotechnical measures." Yet their concession was an exercise in protective coloration, and Makarov tried to limit the actual implementation of many of these nature-transformation schemes for the zapovedniki to the best of his ability.

Nevertheless, it was politically impossible to stay aloof from some high-profile campaigns. Regarding the acclimatization of the muskrat, the raccoon-dog, the sika deer, and some other large game animals (especially ungulates), there was almost no choice. Although the elimination of wolves and other large predators in the reserves had greater internal support, particularly if the reserves also harbored endangered herbivores, there too the authorities exerted uncontestable pressure. All the while, campaigns against the wolf were raging outside the reserves; the last family of wolves was exterminated in the Okskii zapovednik in 1954 and in the Voronezhskii in 1955. And, depending on the reserve, foxes, bobcats, wolverines, bears, cormorants, seagulls, marsh hawks and other hawks, and owls also found themselves at the wrong end of a gun.[6]

Acclimatization intensified under Malinovskii, although not every attempt resulted in a thriving population (and consequently a biotic disruption). Nine musk deer were released in Denezhkin kamen' in the Urals, for example, but by 1959 all the animals were dead. "The results of the acclimatization of the sika in zapovedniki were various. However, in all cases where the deer survived, regular winter feeding and other biotechnical measures were maintained," wrote Filonov. Ironically, when some of the reserves to which the sika had been acclimatized, such as the Buzulukskii bor and Kuibyshevskii zapovedniki , were liquidated in 1951, the unforgiving hand of natural selection also carried off the deer.[7] The only successful sika introduction was in the Khopërskii zapovednik , where twenty-seven animals released in 1972 grew to 1,800 by 1977.[8] More "successful" attempts involved the

raccoon-dog (Nyctereutes procyonides ), the muskrat, and the American mink, but much of these efforts were now largely conducted outside of zapovedniki , in forest plantations or areas designated for legal hunting.[9]

Other measures also continued or were expanded. Hay mowing for supplemental feeding or for feeding the Mordvinian zapovednik's own stock from 1954 through 1967 reached 9.4 tons per year, and in Il'menskii (from 1937 to 1960) averaged about 24 tons annually. Twig bunches (veniki ) were collected on a massive scale in some reserves, such as the Mordvinian, Il'menskii, and Okskii.[10]

But Malinovskii's beloved preoccupation in his new reserve system was forest management. From this perspective, ungulates were as much a pest to be eliminated as an economic amenity to be promoted. In quite a few zapovedniki such as the Crimean and Voronezhskii, deer were shot or, after 1952, captured and relocated.[11]

In reserves that had been "liquidated" and turned over to the USSR Ministry of Forestry, commercial logging soon began. There were important exceptions, such as the reserves of Lithuania, now classified as "watershed" forests protected from lumbering, and areas where the commercial potential was particularly low. The former Troitskii forest-steppe zapovednik constituted such an area, and it had the relative good fortune to be handed over to Perm' State University, which rechristened the territory an "Instructional-Experimental Forest Plantation." Here, the supportive local oblast' Executive Committee declared the area a zakaznik (a protected territory established usually for a period of five or ten years) until 1961, with all economic activities or alterations of the natural conditions prohibited. Thus, with the connivance of the local political authorities, Troitskii de facto remained a zapovednik , but now of Perm' University. Perhaps the most visible change was in the kinds of research pursued. More emphasis was placed on developing strategies for pest control, reclamation of salt pans and salt meadows through targeted afforestation with appropriate tree species, and studying the relationship between tree species and soil chemistry. Basic research continued to be pursued vigorously as well.[12]

The contrast between zapovednik management in the pre–and post-Malinovskii eras, although significant, has perhaps become exaggerated in the memories and perceptions of partisans of nature protection. True, acclimatization and predator control were conducted as protective coloration under duress during the Makarov years, whereas Malinovskii promoted those policies with enthusiasm. Yet the ecological consequences of acclimatization and predator control were not discernibly different before and after 1951.[13] In the memories of scientist activists, understandably, there has been a tendency to picture the zapovedniki before 1951 as idyllic and during the Malinovskii period as degraded. Certainly, from the perspective of scientists'

input and autonomy, not to mention the more mundane question of employment, that portrait of the reserves system reflects indisputable realities. Regarding acclimatization and the extermination of predators, however, the truth is not nearly as clear-cut.

The Academy of Sciences Commission on Zapovedniki

Bright spots such as Troitskoe or Lithuania were only local responses. The first coordinated response of the scientific community following the August 1951 calamity was not long in coming. With the quiet blessing of the new president of the Academy, the chemist Nesmeianov, who had just succeeded the late Sergei Ivanovich Vavilov, and of the Academy's scholarly secretary, A. V. Topchiev, a major new commission was created on March 28, 1952, attached to the Academy's Presidium: the Commission on Zapovedniki .[14] Like Vavilov before him, Nesmeianov had to walk a fine line between official obeisance to regime policy and his own vision of the welfare of science. This is well illustrated by a visit paid to him in early summer 1952 by Aleksandr Leonidovich Ianshin (see figure 12) and Vera Aleksandrovna Varsonof'eva in their capacities as co–vice presidents of MOIP. Their goal was to try to convince the Academy president personally to join the fight to restore at least some of the zapovedniki .[15]

Varsonof'eva started to speak about the importance of the Kondo-Sos'vinskii reserve on the eastern slopes of the Urals and the Barguzinskii zapovednik on the eastern shores of Lake Baikal in restoring the population of sable. Perhaps exploiting his status as a chemist, Nesmeianov replied to the geologist: "Vera Aleksandrovna, why do we need to worry about breeding all those fur-bearing animals these days? With the help of chemistry we can produce fur of any quality, any color, and any degree of beauty. We are now living in the century of synthetics and not natural products," he concluded, refusing help.[16]

Looking back, Ianshin was convinced that Nesmeianov was using a little protective coloration of his own to avoid the opprobrium of scientific public opinion. A Party man, indeed, a member of the nomenklatura , Nesmeianov was obliged to obey and fulfill the instructions and decrees of the Party once they were adopted. For that reason he could not be openly associated with the struggle against the 1951 Party decision. Yet, his honor as a member of scientific public opinion was called into question by his inability to join this crusade. Hence the need to present his position in terms of personal aesthetics, colored by his background as a chemist, so as to avoid an embarrassing admission that to protect his position he had no choice but to refuse assistance.[17]

Figure 12.

Aleksandr Leonidovich lanshin (1911– ).

Nevertheless, the Academy president allowed Vladimir Nikolaevich Sukachëv, dean of Soviet botanists and director of the Academy's Institute of Forests, a surprising degree of freedom to use both his Multidisciplinary Scientific Expedition on Problems of Shelter Belts as well as the new commission as havens for out-of-work zapovednik staff and activists in the area of nature protection.

With Sukachëv as chair of the Commission on Zapovedniki , Makarov and Dement'ev were named two of his four deputies, the others being the aca-

demician Andrei Aleksandrovich Grigor'ev, a geographer and conservation stalwart, and Nikolai Evgen'evich Kabanov, a biologist working in the Institute of Forests. The remaining membership was no less distinguished.[18]

Barely two weeks later, the commission had already roared into action, convening the first meeting of its executive Bureau. Preoccupied with the continuing political troubles of his interdisciplinary Shelter Belt Expedition as well as an unexpected initiative, probably with its source in the Central Committee, to move his Institute of Forests to eastern Siberia (Krasnoiarsk), Sukachëv was unable to attend. Indeed, according to his close friend and deputy director of the Expedition, Sergei Vladimirovich Zonn, Sukachëv's blood pressure was so consistently high during those days that his doctor did not know whether the academician would live to see the next morning.[19] Happily, Sukachëv had a coterie of brilliant and dependable associates whom he had either attracted to his Institute or rescued from persecution by Lysenko and others, and to them he could confidently delegate some of his important scientific-political responsibilities. One of these was Nikolai Evgen'evich Kabanov, who in the early years of the commission more often than not sat as acting chair and convener.

Under Kabanov's direction the commission developed a work plan for the first half of 1952. Among its central responsibilities was examining the scientific research plans of Malinovskii's new Main Zapovednik Administration of the USSR Council of Ministers, particularly because the new decree on zapovedniki of August 1951 specifically assigned research-related "methodological leadership" to the USSR Academy of Sciences.[20] The dogged persistence and cunning of scientific public opinion now placed oversight of zapovednik research in the hands of Malinovskii's enemies: the old guard nature protection activists and elite field biologists of the nation. Scientific public opinion would not allow its "free territories" to be dispossessed, even if it meant a protracted and grueling guerrilla war. And a guerrilla war is what the central authorities got.

At a meeting of the Bureau on July 9, 1952, with Malinovskii's deputy director for scientific research Aleksei Ivanovich Korol'kov present, the forestry plans of the Main Administration came under fire. One of the most eloquent defenses of the special function of zapovedniki as etalony was made by Makarov, who insisted that the reserves must find a way of pursuing forestry under conditions of zapovednost' (inviolability): "Here [in Malinovskii's plans] a mistake has crept in. [Research] needs to be conducted not [only] within zapovedniki , but under conditions of zapovednost' ."[21] Forestry needed to promote the "natural" regeneration of "natural" forests.

Malinovskii's plans now came under accelerated attack in the commission. At a December 10, 1952 meeting, A. P. Protopopov, who was asked

to testify, demonstrated that he had lost none of his acuity or his mettle as he subjected Korol'kov, who then held the rank equivalent to a deputy minister, to inconvenient questioning:

I want to receive an answer from the representative of the Main Zapovednik Administration how we should critique [his plans] in the future. A question has emerged: "What kinds of institutions are we looking at here? What, in fact, are the Main Administration's zapovedniki? " The Main Administration uses the term zapovednoe khoziaistvo [management of a zapovednik oriented toward the exploitation of its resources, even if experimentally]. What are the zapovedniki, scientific-research institutions or zapovednye khoziaistva? This term elicits incomprehension. As I see it, zapovednoe khoziaistvo is an impossibility. There can only be khoziaistvo zapovednika [administrative management of a zapovednik ].[22]

Korol'kov was equally outspoken:

I am shocked by the question "What is a zapovednik?" The USSR Council of Ministers has already settled this question. Comrade Protopopov will find a exhaustive response [to it] in the statute [on zapovedniki ]. . . . It must be kept in mind that there is a whole group of objects of economic interest in the zapovednik. Experience has shown that it is impossible to practice forestry without cutting and treatment [of trees]. Economic measures must be carried out.[23]

When the commission finally drafted its official assessment of the scientific work plan of Malinovskii's reserves system for 1953 it noted that the Main Administration had taken some of the criticism received at the December 10 meeting into account, which improved the plan. However, the commission continued, "a second look at the plans sent to us shows that the Main Zapovednik Administration has still not adequately taken to heart the observations and recommendations of the Commission on Zapovedniki."[24]

The target of the commission's displeasure was the entire section "Scientific and Scientific-Technical Measures for Implementing Zapovednoe Khoziaistvo." "This whole section deserves the most comprehensive and critical discussion at the Scientific-Technical Council of the Main . . . Administration," the report noted. While projected studies of the ecological effects of the flooding of the shores of the Rybinsk reservoir were praised, the attempt to call a whole slew of managerial and technical measures "fundamental research" was roundly opposed.[25]

Malinovskii sought to keep his Scientific-Technical Council completely isolated from any contacts with the old guard on the commission, a state of affairs bitterly condemned by Geptner.[26] By March 1953 the Academy of Sciences and its commission were so frustrated by Malinovskii's lack of cooperation that they tried to get relieved of their responsibilities for oversight of the scientific work done by the Main Administration. Of course, they also no longer wished to be held legally responsible for that research, a responsibility overseen by the USSR Ministry of State Control.[27]

When the nature reserve system was "reorganized" there had been zapovedniki that were already subsumed under either the USSR Academy of Sciences or one of the Academy's republican affiliates. With the "liquidation" of most of the reserves, the Academy inherited an additional contingent that Malinovskii rejected for his own system, largely because the reserves lacked significant forest cover. Thus, by February 1953 the Academy system controlled fourteen reserves.[28]

By May 1952, Sukachëv, together with corresponding member I. V. Tiurin, director of the Academy's Institute of Soil Science, tried to roll back the decree of the previous year, beginning with the case of only one zapovednik, the Poperechenskaia steppe. Writing directly to Malenkov at the Central Committee Secretariat, the two scientists argued against the transfer of the zapovednik from the Penza Pedagogical Institute to a nearby collective farm, since the total area of the reserve, 200 hectares, would hardly represent an appreciable gain for the "Proletarian" collective farm (6,000 hectares). Meanwhile, those 200 hectares were among the last parcels of undeveloped northern forest-steppe. At a meeting organized by the Penza oblispolkom of March 5, 1952, they noted, a great many local workers and specialists spoke out in defense of continued protection for the area, as did the Penza branch of VOOP and the Biology Division of the Academy.[29]

Malenkov examined the letter ten days later, and marked in the margins that A. I. Kozlov, head of the Agricultural Department of the Central Committee, should look into it. However, Malenkov significantly made the further notation, "We must act in accordance with the decision of the Government concerning zapovedniki. Report back."[30] On June 13, Kozlov's deputy V. Iakushev wrote back to Malenkov:

The head of the Main Administration, . . . Malinovskii, considers it ill advised to reexamine the decision of the USSR Council of Ministers of October 29, 1951 . . . because pristine, unplowed lands continue to be preserved in the Tsentral'no-Chernozemskii zapovednik . . . where practical scientific work on problems of the generation of strong black earth soils is being conducted. I also spoke with the secretary of the Penza obkom, Comrade Lebedev, who informed me that the obkom . . . did not support the recommendations of Comrades Sukachëv and Tiurin.

Neither did the Agricultural Department.[31] This time, however, Sukachëv and Tiurin did not fold, taking their case to Academy president Nesmeianov. Another attempt was made the following year.

For the short term, Stalin's death on March 6, 1953 worsened the situation of zapovedniki in the Main Administration. In the immediate aftermath of the dictator's death there was a significant rearrangement of ministerial responsibilities at the USSR level. Stalin was succeeded by Nikita S. Khrushchëv as first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist

Party of the Soviet Union. Georgii M. Malenkov replaced Stalin as chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers (premier). One change entailed the abolition of the Ministry for Supplies (temporarily, it turned out), which was merged with Agriculture, with A. I. Kozlov (also temporarily) replacing Benediktov as minister of the enlarged superministry of Agriculture and Supplies. Although Malinovskii was not removed as head, his Main Administration was demoted from its status as an all-Union ministry and subsumed as a somewhat minor department under the Ministry of Agriculture and Supplies. As had happened in the 1920s, zapovedniki were trapped in the unfriendly embrace of the "economic commissariats." Little help could be expected from the minister, Kozlov, whose prior position made him Malenkov's right-hand man on the Secretariat for agricultural and land-use matters, and who was partly responsible for the reserves' current plight.

That seemed to leave only one route: to have the Academy system somehow become the nucleus of a new expansion. In his last major speech before his death, Makarov expressed the hope that the Academy would indeed prove to be the savior of his life's work. After all, the zapovedniki, he told a convocation of directors of nature reserves of the Academy system in the spring of 1953, "serve the general goals of the development of science."[32] Despite the importance of each reserve preserving its own personality, Makarov also stressed the need for common goals, common scientific perspectives, and common methods, so that the results of research at the various reserves could be compared. Here, too, the Commission on Zapovedniki had already begun work, drafting an overall statute for the Academy system "independent" of the statute on zapovedniki drafted by Malinovskii one year earlier.[33] It was crucial always to remember that zapovedniki were "a huge natural laboratory, a laboratory of nature" rather than a laboratory in nature, as Malinovskii would have it.[34] Making the obligatory rhetorical bows to "Michurinist biology" and "Pavlovian physiology," Makarov concluded by emphasizing the crucial role of the reserves also in the preparation of graduate students in their aspirantura (graduate training) and as a research base for those mature scholars seeking the degree of doctor of science (doktorantura ) both inside and outside the Academy systems.[35] A little over two months after giving this speech, Makarov died, and the commission was spurred to even more energetic activity to honor his legacy.

The new draft of the statute on the Academy's reserves was completed on September 18, 1953. The reserves were declared to be "independent scientific research institutions" of the Academy systems, with their own staffs of scientists and technical and support workers, and with goals that highlighted the twin missions of protection and fundamental research.[36]

Despite the political confusion following Stalin's death, the country also had a new atmosphere of guarded hope and of greater freedom. True, no one knew who was on top—Khrushchëv or Malenkov—but for the scien-

tific intelligentsia that was not a major preoccupation. As 1953 glided into 1954, the scientific intelligentsia mobilized to reclaim scientific autonomy and restore the "geography of hope," in many ways vastly outpacing their colleagues in literature who were creating the first "thaw."

The Rise of MOIP as a Center of Resistance

When Varsonof'eva and Ianshin went to see President Nesmeianov about enlisting him in the fight to restore the zapovedniki, they came as representatives not of VOOP but of MOIP, the Moscow Society of Naturalists, Russia's oldest scientific society.[37] To understand why they presented themselves in this fashion and to understand how MOIP came to represent a center, and later the center, of scientific public opinion, we must survey the history of that society from 1948 on.

As late as the early 1940s, MOIP still had a deserved reputation as a sleepy academic society.[38] Its library, adjacent to the Gor'kii Library of MGU's old campus opposite the Manezh, was frequented largely by older men and women poring over biological arcana under the stern gaze of a huge stuffed owl and equally lifeless early nineteenth-century portraits of MOIP's founders. The society's president was the ancient and revered Nikolai Dmitrievich Zelinskii, a chemist and prerevolutionary relic who still favored the round, brimless black academician's cap, which vaguely resembled Central Asian Muslim headgear, the tiubeteika. In a word, MOIP was quaint.

Two features distinguished it from all other Soviet societies. MOIP had maintained an almost unbroken tradition of non-Communist leadership, from Menzbir to Zelinskii (although Sukachëv joined the Party in 1937, he was clearly heterodox) and now to Ianshin. Even such venerable and progressive societies as the Geographical Society of the USSR or the Mineralogical Society, two others that survived the early 1930s and that were almost as old as MOIP (f. 1805), were obliged to select Party members as their presidents. The difference was that whereas they were chartered within the system of the USSR Academy of Sciences, MOIP was tucked away under the aegis of Moscow State University, almost out of bureaucratic view.[39]

Like VOOP, MOIP united the scientific, preeminently biological and geographical-geological intelligentsia across Russia and even the Soviet Union, despite its local name. Though the society had no organizers, branches emerged on local initiative in Kalinin (Tver'), Riazan', Sverdlovsk (Ekaterinburg), Tomsk, L'vov, Uzhgorod, Alma-Ata (Almaty), Aral'sk, and Sukhumi, among other places, constituting an informational network across the country. As Nikolai Nikolaevich Vorontsov noted recently, an entire history could be written about science "on the periphery" in Russia. This periphery was a product of many factors, including the flight of many field

biologists to distant zapovedniki and antiplague stations, to pest-control stations, and to remote research and teaching institutions, partly in the hope of avoiding the repressions that were continually sweeping the "center."[40]

In the words of Oleg Nikolaevich Ianitskii, "The Moscow Society [of] Naturalists was arguably one of the few long-established social organizations that was not taken over entirely by the state. In any case, its official structure differed from the state-determined model. . . . The organizational principles set out in its constitution were democratic, and its members did not have to be professional scientists, but were merely required to be involved in the scientific life of society."[41]