The Moscow State University Biology—Soil Sciences Student Brigade for Nature Protection

The first university students' nature protection circle in the USSR was founded in Tartu on March 13, 1958, uniting students from Tartu State University and the Estonian Agricultural Academy. "Taking up the initiative of Tartu University," as a recent history put it, the students of the Biology—Soil Sciences Faculty (Biofak) of Moscow State University in 1960 founded the first druzhina (nature protection brigade).[1] The curiously anachronistic designation druzhina was not idly chosen. The chronicles tell us that Prince Vladimir, "who loved his druzhina ," consulted with it about affairs of the land and of war. The druzhina was the circle of closest warriors and counselors of the princes of Kievan Rus', the first line of defense of the Russian lands. "All this is known, of course, only by historians," writes modern-day druzhinnik Ksenia Avilova.

Nevertheless, when the Komsomol enthusiasts, having decided voluntarily and without any thought of gain to defend nature against doltish assaults, called themselves the druzhina as of old, they immediately and precisely defined the sense and thrust of their work: active activity [aktivnaia deiatel'nost '] , struggle, and the protection of Russian nature from evil, from soullessness, and from a lack of care for it. In that way the word druzhina acquired its contemporary meaning, distinguishing itself from all other circles, clubs, and societies that frequently exhibited only the external facade of solidarity.[2]

Vadim Tikhomirov, the druzhina 's faculty adviser, commented on this lexical matter as well: "The very word 'druzhina ' was a happy choice. . . . In it we see reflected the striving for active efforts, for struggle, and not for meditations on nature protection themes. It presumes a certain level of organization and solidarity and, more than anything, a strict sense of civic responsibility [strogaia obshchestvennaia otvetstvennost '] even while preserving the conditions of voluntary enrollment."[3]

That account, however, omits a much more recent antecedent, the druzhinniki , who had just been brought into being by Khrushchëv as part of his vision of a transition of the Soviet Union from a "dictatorship of the proletariat" to an "all-people's state." The Party Program that followed the Twenty-first Party Congress in February 1959 promised that organs of state

power would gradually become organs of public self-administration, in keeping with the withering away of the state that Marx and Engels had promised.[4] One of the first areas selected for this transition by the Soviet chief was the maintenance of public order, and squads of druzhinniki with their telltale red armbands became ubiquitous at sports events, parades, and even university entrance checkpoints following a decree of March 2, 1959, although their experimental precursors date to 1957.[5] The Moscow University druzhina could point to Khrushchëv's druzhiny as a potential source of legitimation while creating a social space for civic activism and public self-administration far more independent than what the state had intended.[6]

The origins of the MGU druzhina actually go back to 1959 as well, when a university student subsection was created under F. N. Petrov's Section on Nature Protection, with the active patronage of the president of MOIP's Biology Division, Nikolai Sergeevich Dorovatovskii, and its secretary, Konstantin Mikhailovich Efron. At the time, the most active student members were Boris Vilenkin, Maria Cherkasova, and V Baranov. "The numerous excursions and trips organized were motivated by the urge to apply the members' personal efforts in the defense of living nature," recalled Vadim Nikolaevich Tikhomirov, one of the subsection's organizers. The students were looking for "active efforts" and "struggle," motivated not by anti-Soviet attitudes but by a fierce impatience with the imperfections of the system. Many were members of the Komsomol who had acquired credentials as "citizens' inspectors" for nature protection. The first student inspections throughout Moscow oblast' to combat poaching and trips to the forest to prevent the logging of fir trees for the New Year date to this MOIP period of the movement.[7] The students proclaimed: "We've had enough talk about purity. Let's start cleaning up!"[8]

Aside from those dramatic undertakings, the students addressed numerous groups, from teachers to factory workers, and organized seminars to upgrade their own knowledge of conservation issues and biology. Through MOIP, they were able to attract speakers of the stature of soil scientist David L'vovich Armand. This exposure to scientific advocacy for nature protection, with all of its customs and rules of polemics and conversation, socialized the students to the social identity of nauchnaia obshchestvennost' .[9] For many students, however, devotion to the older cult of science with its rules and ethical norms had less appeal than the tug of adventure and a life of action.

Spurred by news of independent student organizations in Tartu and Astrakhan (Iu. N. Kurazhkovskii's "For a Leninist Attitude toward Nature," founded earlier in 1960), the students soon went their own way, with the reluctant blessing of the MOIP leaders.[10] Geography played a role in this turn of events. The headquarters of MOIP was on the old campus, in the

Zoological Museum off Manezh Square. However, the students lived and studied at the new campus, miles away on Lenin (Sparrow) Hills. This physical separation facilitated the creation of a distinct student identity.

The development of an autonomous society was quickened by the emergence of a group of exceptionally independent-minded first-year students in Biofak in 1960. As Tikhomirov relates it, "In the majority, they were shaped by having been in the various young naturalist circles: KIuBZ, the VOOP circle led by Petr Petrovich Smolin, and the circle within MOIP led by Anna Petrovna Razorënova. These students led by Evgenii Smantser sought out teachers who were also deeply troubled by problems of nature protection. As a result of the combined efforts of students and faculty came the birth of the druzhina ."[11]

Much like field biology itself, a region of natural science that seemed to draw in those who experienced a special need or delight in studying life in its unfettered condition, the druzhina attracted the most independent, self-reliant, and, it appeared, most sensitive students. They were also, in their own way, those most aware of social wrongs and, on some still dimly conscious level, of the possibility that the Soviet vision had taken a drastically wrong turn. It is likely that no one will improve on the portrait provided to us by druzhina veteran Ksenia Avilova: "It is natural that at the origins of this unique coalescing of youth, born as it were as a sign of the times on the eve of the RSFSR law on the protection of nature, stood individuals who were out of the ordinary. . . . [I] n the far gone days of 1960 this kind of activism with respect to nature was a reflection of an improbably daring, even dangerously bold view of life."[12]

At the October 1960 Komsomol conference of the members in the Biology—Soil Sciences Faculty, the activists secured support for the creation of a druzhina po okhrane prirody (nature protection brigade). On December 13, 1960, at a meeting of the Komsomol of the faculty and nature protection activists, the "fighting brigade" was formally christened. Its first "commander" (komandir ) was biology student Evgenii G. Smantser. Biofak dean Nikolai Pavlovich Naumov named dotsents Vadim Nikolaevich Tikhomirov and Konstantin Nikolaevich Blagosklonov, who later coauthored the first university textbook on nature protection and conservation biology, as the kuratory or faculty advisers of the new group.[13] Both were active in MOIP and VOOP and they were well positioned to convey the old-line tradition to the up-and-coming generation of elite field biologists.

As the "zoological" half of the faculty leadership, Blagosklonov trained the students in the skill of observing bird behavior. The author of an internationally known handbook on the protection and attraction of birds, Blagosklonov had organized "Bird Day" in the 1920s with some Young Naturalist groups. He also supported youth programs such as the Zvenigorod

summer schools, KIuBZ, and VOOP's youth section, in which he continued to be active despite the transformation of VOOP's leadership into a sinecure for retired Communist operatives. Blagosklonov's other great strength was in organization. For more than twenty years he organized biology "Olympics" at Moscow State University, summer camps for nature protection, and a host of other events. He was also an eager propagandist for nature protection, writing innumerable articles and appearing on radio and television.

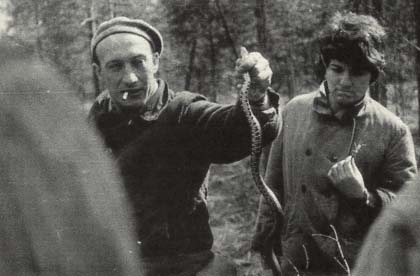

As the "botanical" half, with particular expertise in floristics and taxonomy, Tikhomirov (see figure 20) was an invaluable guide to the world of vegetation. His students were treated to exhaustive but also exhausting training: two months in the field in Mordvinia on the upper Volga after the first year, geobotanical field work and ecology in the Moscow region after the second, a transzonal field journey south to the Caucasus or Crimea together with soil scientists, and then a 10,000-kilometer odyssey around central Russia, including the southern steppes. Various zapovedniki served as training bases. Nature protection based on a profound scientific knowledge of vegetation was the emphasis. Those who sought to spend their summers sunning themselves on the beaches in Batumi were encouraged to select another area of specialization. The students had to love botany enough to consider a grueling field trip a vacation. Tikhomirov brought more than technical knowledge to the druzhina ; he was its moral compass, with his militancy, personal daring, and charisma.[14]

In those first few months, the druzhina began with a band of forty-two stalwarts, an impressive number for such a risky and dubious cause. In that first cohort, two members were involved with organizing and providing lectures and two more worked with the youth group at MOIP, a residual link to the parent society. Three served on the editorial commission and three more started a separate section concerned with the fight against water pollution. Almost half were involved in the antipoaching patrols, which were later (1974) christened "Operation 'Shot'" (Programma 'Vystrel' ). Instruction and training were a central part of preparing the druzhinniki for this dangerous work. Because the druzhina from the outset was under the aegis of both the Komsomol and VOOP, as members of the latter, druzhinniki were able to get credentialed as "citizens' inspectors for nature protection," which allowed them to apprehend violators of Soviet nature protection and hunting laws and to confiscate their equipment and catch.[15]

Regular antipoaching operations began in earnest in the autumn of 1961. Paraphrasing Smantser's memoirs, Sviatoslav Zabelin described the scene in those days (see figure 21): "In the evening upon the druzhinnikis arrival at the base, the atmosphere was jolly around the far from sober dinner table. But from early morning on followed the inspection, which involved a profusion of confrontations with violators who had no suspicion about the existence of hunting and fishing regulations and relied in all questions on the

Figure 20.

Vadim Nikolaevich Tikhomirov (1932–1998) and

Tat'iana Bek, druzhina komandir (leader), mid-1960s.

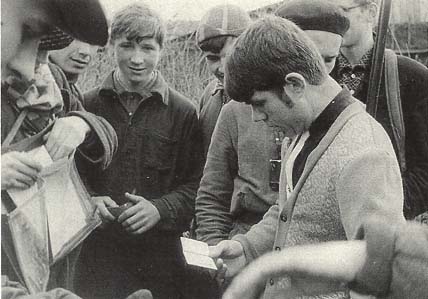

Figure 21.

Druzhinniki inspecting hunting documents, mid-1960s.

power of their fists and their lungs."[16] On rare occasions the raids ended in tragedy; at least six druzhinniki were shot dead during these hunting checks, creating an aura of danger and responsibility around the druzhiny . The group also conducted raids on the Kalitnikovskii open-air market, detaining those who were putting songbirds up for sale.[17]

Targeting ordinary citizens, albeit lawbreakers, reflected the political immaturity of the druzhina movement. From the standpoint of theory, the movement failed to develop a thoroughgoing socio-politico-economic analysis of the roots of the destruction of natural amenities in their society. From the standpoint of tactics, these raids alienated the great majority of the workaday public from the students. In many cases those who were fined or whose merchandise was confiscated were those toward the bottom of the Soviet social ladder, trying to earn a few rubles or bring back a partridge for the family pot. Despite the physical danger of flushing out poachers, the students were going after relatively minor offenders while major bosses, who were not only poaching but poisoning the rivers, lakes, streams, and air, were conveniently ignored. No wonder the antipoaching campaign alienated the masses from these elite students, as Tikhomirov obliquely recognized: "The attitude to its work on the part of the population was, as a rule, hostile. The activities of the druzhinniki often met with total incomprehension, especially when they affected the personal interests of citizens regarding the use of forests, hunting, or fishing. . . . It was a rare encounter in the forest that concluded without the use of force or some other sort of extreme action, and there were shoot-outs."[18]

The authorities had little use for the student raids, either. "We would frequently hear such outbursts [from them] as 'You what? Defend nature? From whom? From our Soviet person?'" Many officials even considered their cause "harmful."[19]

Even in the Biological Faculty itself, the stronghold of scientific public opinion, some questioned the wisdom of letting the students go off into the woods to catch poachers. Rebutting these misgivings, Tikhomirov emphasized the larger social meaning of the students' activities: "But it was precisely [these questions] that demonstrated that [the critics] had completely failed to understand that our foremost task was the socialization of these future specialists, forging their intellectual and political outlooks as well as molding them as citizens."[20]

By the group's official first anniversary in December 1961, a conference had been organized on the emerging problems surrounding Lake Baikal, a rather large and impassioned meeting held on the forestry experiment "Kedrograd" in the Altai, and four wall newspapers published. And Tikhomirov thought that it was time to create druzhiny in other higher educational institutions around the USSR.[21]

The next year's activities saw the New Year's tree campaign move to

Moscow railroad stations where, with the knowledge and cooperation of the stationmaster and militia, buyers and sellers alike were apprehended; in all, 800 trees were seized. It also marked an inconclusive attempt by the Komsomol of Biofak to disown the druzhina by preventing it from delivering its annual report. This and an investigation in November 1962 by the Party Committee were potentially damaging.[22] But the druzhina weathered these squalls, mainly thanks to the support of Naumov and his faculty, again demonstrating the ideals of obshchestvennost' in action.[23]

By the following year, the Party Committee of Biofak was showering the druzhina with compliments despite a few uncomfortable moments in early 1964 when apparently drunken druzhinniki on a trip to the Kyzyl-Agachskii zapovednik in Azerbaijan even engaged in some poaching themselves. Routines developed as komandiri and other posts were rotated every year. The campaigns netted increasing numbers of violators (see figure 22), and the druzhina became a visible and important institution in Moscow University's student scene, even if membership remained modest.

Like its parent, the druzhina was a counterculture. Dmitrii Nikolaevich Kavtaradze, a former leader of the group during the early 1970s, compared it to a "military unit." "Some people were influenced by it to such an extent that the whole course of their lives was altered."[24] Group loyalty was especially great in the druzhina (see figure 23)—partly because so many of its members had already been socialized in the VOOP and MOIP youth groups and in KIuBZ. The geologist Pavel Vasil'evich Florenskii, who had been in KIuBZ, speculated that this powerful bonding ethic had its origins in the brotherhood of the Tsarskoe Selo Lycée and in later traditions of solidarity within university student culture (studenchestvo ).

In the words of Oleg Ianitskii, the druzhina and its later offshoots were spreading "the 'small is beautiful' virus" in a system based on gigantomania. Inevitably this generated tension between the druzhiny and their official sponsors in the Komsomol and VOOP. As Ianitskii notes, "Under our conditions, these contacts did not in any sense amount to a compromise between the two sides; each was playing its own game. The people from the system considered that the independent organizations could be held in check, and that they were a useful valve for letting off the steam of popular dissatisfaction. The club leaders hoped that as they gained more muscle, they would gradually reconstruct the System from within."[25]