Fifteen—

Nosferatu , or the Phantom of the Cinema

Lloyd Michaels

When Georges Méliès's camera jammed on that famous, if probably apocryphal, afternoon at the Place de l'Opéra, transforming the bus he had been shooting into a hearse during projection, he glimpsed for perhaps the first time the ghostly quality of the cinema's particular mode of representation. That phantom image of the hearse has proven to be an evocative symbol of film's unique way of simultaneously deceiving and enthralling the spectator by substituting an illusory presence for an absent referent, rendering as "undead" a lost object by animating projected shadows and light, often revealing the disturbing contours of familiar shapes. Filmmakers and audiences ever since have been attracted to the depiction of spirits and monsters that not only seem to express certain imperfectly repressed human desires but that also may reflect the idiosyncratic signifying process of the cinema itself. Certainly Mary Shelley's monster, Robert Louis Stevenson's Mr. Hyde, and Bram Stoker's Count Dracula now seem rather long-winded intellectuals compared to their original movie incarnations. Is it because as the offspring of uncontrollable technology, doubles of unstable wills, or fleeting creatures of darkness these celluloid characters exhibit something of the intrinsic nature of film?

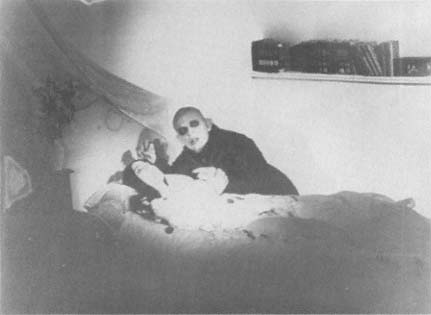

Among the gallery of screen monsters, the vampire may be especially well suited to portray both the parasitical quality of the film artist's manipulation of the audience and the elusive, insubstantial nature of the film image.[1] Unlike the grotesque, omnipotent, larger-than-life creatures of most horror movies, the vampire remains a phantom —a vision of uncertain substance—rather than a certifiable monster . (See figure 28.) Christian Metz and John Ellis, among others, have elaborated on how the signifier in film must always reproduce a phantom of its referent. "The cinema image is marked by a particular half-magic feat in that it makes present something

Figure 28.

The shadow of Max Schreck, perhaps the most frightening vampire

to hit the big screen, looms in F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1922).

that is absent. The movement shown on the screen is passed and gone when it is called back into being as illusion. The figures and places shown are not present in the same space as the viewer. The cinema makes present the absent; this is the irreducible separation that cinema maintains (and attempts to abolish), the fact that objects and people are conjured up yet not known to be present" (Ellis, 58–59). Metz makes much the same point by contrasting cinema with the theater, noting how the screen presents not the real objects and persons on stage, but only an "effigy, inaccessible from the outset, in a primordial elsewhere , infinitely desirable (= never possessible)" (61). Thus, the movie spectator "pursues an imaginary object (a 'lost object') which is . . . always desired as such" (59). The vampire frightens us with its shadow rather than its substance; it is not larger than life but rather "undead"; it evokes not merely revulsion but also desire. As a paradigmatic creature of the cinema, especially in Murnau's Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens, 1922) and Herzog's remake, Nosferatu, the Vampyre (Nosferatu, Phantom der Nacht, 1979), the vampire on film represents the imaginary so effectively because it is the imaginary (Metz, 41).

In addition to these German versions of the vampire myth, there have

been innumerable American and British adaptations, the most noteworthy of which include Tod Browning's Dracula (1931), Terence Fisher's Horror of Dracula (1958), and John Badham's Dracula (1978), not to mention the dozens of sequels, spin-offs, and parodies. During 1992, a fashionable year for vampire revivals, Buffy the Vampire Killer and Francis Coppola's Bram Stoker's Dracula appealed to widely diverse audiences. Each of the five major retellings to date, starring Max Schreck, Klaus Kinski, Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee, and Frank Langella in the title role, has sufficiently revitalized the power of the original novel to refute Alain Resnais's oft-cited rejection of adaptations as "warmed over meals." Murnau's and Herzog's Nosferatus , however, remain more resonant and compelling than the other Dracula movies for two related reasons: first, they present the count as a complex, even sympathetic character rather than the evil monster of Stoker's novel; second, they suggest a linkage between this indefinable characterization and the phantom images created by the cinematic apparatus. Their modernity, in short, derives from a certain self-reflexiveness missing in the other versions. Unlike their English-speaking counterparts, Schreck and Kinski manage to signify elusiveness rather than presence, lack rather than excess, entropy rather than lust. Their Draculas are less the doubles of perverse creative energy than the phantoms of the cinema itself.

Because it follows so closely the visual design of Murnau's original—essentially copying the costuming, makeup, plot structure, and performance style, borrowing some of the dialogue ("What a beautiful throat your wife has!") and camera angles, even shooting the very same buildings in Lubeck that Murnau had employed—Herzog's Nosferatu is a true remake rather than an adaptation, despite its creator's claims. While Herzog has said, "We are not remaking Nosferatu , but bringing it to new life and new character for a new age" (33), his film, unlike the others, cannot be fully appreciated without knowledge of its source (his title indicating that source to be Murnau's film and not Stoker's book), allowing the audience to reexperience many sequences by his employment of nearly identical compositions and blocking. The total aesthetic effect goes far beyond the usual allusions to certain images (rats, cut fingers, ruined castles, abandoned ships) or dialogue ("I never drink . . . wine"); instead, Herzog has conceived every moment with the original in mind, "bringing it to new life" as the "undead" inspiration—the unseen presence—behind his own creation. The parallel between his own art and his protagonist's vampirism could not have been far from his mind.

In contrast to Fisher's, Badham's, and Browning's adaptations, all three of which project an animated, elegant, raven-haired, black-caped protagonist—the mass marketed version of Dracula so familiar in cartoons and Halloween masks—Herzog's Nosferatu duplicates the somnambulistic, emaciated, bald-pated figure first incarnated by Max Schreck. Kinski's per-

formance thus brings to life a phantom of a phantom, a doubled double for the eternal melancholy and mystery of human character that the cinema, with its particular mode of representing "lost objects," seems uniquely equipped to represent. Whereas Murnau's silent film projected the deceptive, disturbing, and evanescent aspect of human character through such relatively new cinematic "tricks" as superimposition and negative shots, Herzog employs more subtle self-reflexive strategies to adumbrate the affinities between his central character and his medium. The result, as Lotte Eisner predicted after observing the shooting of Nosferatu, the Vampyre , extends the definition of a remake to something like Murnau's film "reborn" (Andrews, 33).

Through the vagaries of film history, Nosferatu, A Symphony of Horror had already been reborn—or at least restored—before Herzog undertook the project. According to John Barbow, the original negative of Murnau's classic has been lost; thus, the existing prints (now widely distributed in 16 mm and video format) are copies , all of them incomplete, reproduced from Murnau's shooting script and commentary (82). This circumstance compounds the usual ontological status of the film image as a "lost object" and a figure of the "undead." Even the original characters have been displaced: Murnau's shooting script changes the names from Stoker's novel (for example, Dracula is called Count Orlock, Renfield is Knock), and different names are used in different prints of the film (for example, Jonathan's wife may be called Ellen or Nina).

In loosely adapting Stoker's novel to the screen,[2] Murnau simplified the social concerns while significantly expanding the role of the count, making him the dominant character. "Stoker's novel tells of a serious struggle between human systems. The ending is a paean not only to the good and moral but also to the enlightened, social, domestic, and scientific culture of late nineteenth-century England" (Todd, 200–201). Probably influenced by Freud and certainly by German Expressionism, Murnau's concerns are more psychological than social, as is evident in two ambiguous cuts between Nina and the far distant count. In the first of these, while sleepwalking from her bedroom in Bremen, Nina calls out to Jonathan, who lies prostrate before the menacing shadow of the count in his Carpathian castle. An intertitle says that Jonathan heard her warning cry, but the crosscut shows only Dracula retreating in apparent response. In a second sleepwalking sequence, Nina awakens to announce, "He is coming! I must go to him!" but her reference is ambiguous since it follows a shot, not of Jonathan returning by stagecoach, but of Dracula's ship at sea. Earlier, she had kept a vigil on the beach, supposedly for her husband (who left Bremen by land), further suggesting that the film's truest marriage is between herself and the vampire. Indeed, Murnau's other principal transformation of the novel (aside from expanding the count's role) involves making Nina, not van Helsing,

Nosferatu's main antagonist. Whereas in the novel, the woman must be saved from the monster, in the film she willingly sacrifices herself to become his destroyer. Van Helsing, however, is reduced to offering ineffectual lectures on Venus flytraps. The many remaining minor characters in the book are similarly simplified or eliminated. In comparison to Stoker's extended social morality play, Murnau's Nosferatu becomes essentially a tragedy with three characters.

In another departure from the novel, Murnau's count casts a menacing shadow as he stalks first Jonathan and later Nina. Stoker's Dracula, of course, casts no shadow or reflection. While striking in their abstraction of the vampire's horrific threat, these magnified shadows on blank walls also serve as reminders of the cinema's mode of representation. Sabine Hake has noted how early German film before Murnau was marked by "a kind of promotional self-referentiality that draws attention to the cinema and foregrounds its means" in order to "show audiences how to appreciate the cinema and its increasingly sophisticated products, how to deal with feelings of astonishment and disbelief, and how to gain satisfaction from the playful awareness of the apparatus and the simultaneous denial of its presence" (37–38). Murnau continues this tradition from the previous decade, although the self-reflexivity of Nosferatu , like that of the earlier films Hake describes, has little to do with a modernist questioning of the medium. Instead, Murnau explores the technical means available for representing the phantom of character that, for him, lies at the center of the story. In his film, the sources of Dracula's alienation and depravity remain unfathomed: nothing is to be learned of his ancestry, his philosophy, or his personal feelings. The mystery shrouding his character can only be approached through indirection, as in the grotesque shadows that signify his presence.

Murnau's use of other special effects—particularly the negative shot of the coach taking Harker through the forest to Dracula's castle and the superimpositions (double exposures) of the vampire's sudden spectral appearance—can be understood as similar demonstrations of the affinity between the cinema's process of signification involving the play of presence/absence and the ambiguous character of the film's protagonist. The negative image of the stagecoach, with its shrouded windows and horses, extends the haunting effect of Méliès's phantom hearse; the superimpositions seem to defy human corporeality and privilege the uncanny. Even the vampire's ultimate extinction, his dematerialization as conveyed through stop action and a puff of smoke, suggests by metonymy the spontaneous combustion that threatens the film's own nitrate stock. Of course, such subtle implications may have been far from the director's conscious design, but it seems significant that Murnau employs a quite different repertoire of stylistic devices—notably camera movement and depth focus—when he

comes to portray a more ordinary, "realistic," though equally fascinating, character in The Last Laugh (1924).

In setting out to adapt Murnau's Nosferatu, Herzog has retained the basic plot and mise-en-scène while refining the reflexive and expressionistic elements. Despite one reviewer's description of Nosferatu, the Vampyre as "simply Murnau with colour and sound" (Strick, 127), Bruce Kawin has more precisely noted how "no more than three shots are exactly the same in both films (allowing for the fact that Herzog's are in color)" (45). Paradoxically, this homage to the history of German cinema and to the director Herzog considers his country's greatest remains the most personal of all the Dracula films. While remaking Murnau's masterpiece, Herzog has also managed to remake Herzog, exploring the signature themes and stylistic elements that have defined his place as that of one of the seminal artists of the New German Cinema.

Although it is difficult to conceive of a more "faithful" remake, Nosferatu, the Vampyre also alters and even subverts Murnau's original in some significant ways. The most prominent changes involve both foregrounding the collapse of civilized society in the face of Nosferatu's invasion and elaborating the vampire's personal history and psychological motivation. The primary effect of these changes is to reverse the theme of Stoker's novel, the triumph of good over evil, and to undercut the sense of closure in Murnau's film. In Herzog's romantic, subversive ending, Nosferatu lives on in the vampirized character of Jonathan Harker, who flees from the bourgeois town of Wismar (actually Delft) into what Metz might call a "primordial elsewhere, " announcing that "I have much to do." Like the epilogue Polanski attaches to his version of Macbeth, this added scene expresses the director's personal reconception of the thematic implications of the original, an updating of the classic text in response to the exigencies of modern culture. The restoration of order in Shakespeare's and Murnau's work has been superseded by Polanski's and Herzog's vision of chronic malignancy.

Herzog's specific transformations of Murnau's Nosferatu may be organized according to a tripartite taxonomy of adaptation strategies broadly derived from Vladimir Propp: simplification, expansion, substitution (Crabbe, 47). By eliminating the original diary frame (the account of the plague in Wismar by one John Cavillius), Herzog excises the voice of rational authority over the progress of the story and replaces it with the mysterious choral accompaniment of Popul Vuh on the sound track.[3] Similarly, Dr. Van Helsing's scientific lectures have been cut, further subverting any "objective" explanation for the film's irrational events. Herzog's expansions chiefly involve the development both of Dracula's more sympathetic character and of Wismar's more stifling, ineffectual society. Murnau could only suggest the count's enervated, alienated existence through Schreck's performance and occasional crosscutting; Herzog adds dialogue expressing

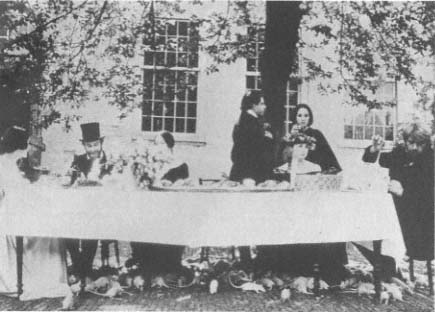

Figure 29.

Horror and sexuality blend in Herzog's Nosferatu, the Vampyre (1979) as the

vampire (Klaus Kinski) approaches Lucy, played by the beautiful Isabelle Adjani.

the vampire's world weariness after witnessing centuries of sorrow, and Kinski speaks in a labored whisper, as if he were breathing through a respirator. Most notoriously, Herzog expands the representation of pestilence by importing thousands of laboratory rats and turning them loose in the streets of Schiedam (after the mayor of nearby Delft had prohibited their release). He also expands the sense of decadence by shooting new sequences of chaos in the town square (antithetical to Stoker's reaffirmation of bourgeois society and quite different from Murnau's orderly scenes showing crosses being painted on quarantined houses and coffins being carried through the streets). In preparation for his pessimistic ending, Herzog substitutes an ominous prelude for Murnau's initial images of domestic bliss (Jonathan picking flowers, Nina playing with her kitten). Thus, the credit sequence of Nosferatu, the Vampyre begins with a sustained tracking shot in a cave of contorted mummies, accompanied by a medieval dirge sung by Popul Vuh and followed by slow-motion images of a bat in flight. In the film's first diegetic scene, instead of tenderly receiving a bouquet from her husband, Lucy Harker awakens from a nightmare.

These transformations confirm Herzog's assertion that he is not simply

remaking Nosferatu but revivifying it. As in all previous versions, however, there remains at the very center of his film the haunting figure of Dracula himself, the mysterious object of both fear and desire. Only in Victor Erice's evocation of James Whale's Frankenstein (1931) in The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) is the monster treated with such ambivalence. Reflecting another crucial change from its precursors, the climax of Nosferatu, the Vampyre depicts Lucy drawing the vampire back to her neck as he begins to withdraw with the arrival of dawn. The bedside tableau clearly portrays the erotic subtext left imperfectly concealed in most versions of the story.[4] (See figure 29.) In this moment, Dracula transcends his previous incarnations as moral monster to become the double of Harker (who first appears whispering words of comfort into his frightened wife's neck as she awakens from her nightmare), the alter ego of Herzog (who identifies with the vampire's romantic restlessness), and the phantom of the cinema.

There are phantoms everywhere in Herzog's text. In addition to the presiding spirit of Murnau, and Kinski's reincarnation of Schreck, Nosferatu, the Vampyre conjures up the ghost of Stoker by restoring his original characters' names and echoes Bela Lugosi's famous line from Browning's Dracula when the count responds to the cry of wolves: "Listen! The children of the night make their music." Roland Topor's performance as Renfield, which drew a mixed response from reviewers, seems more comprehensible when understood as an allusion to the stylized appearances of Peter Lorre in dozens of horror films. Herzog thus evokes the history of what Eisner called Germany's "Haunted screen," in addition to referring to German painting (Caspar David Friedrich's mountain landscapes and ruined castles) and music (the Wagnerian sound track). Finally, Herzog resurrects the ghost of Herzog in a number of ways that reflect his own earlier films: the repertory company of collaborators, including Kinski, Popul Vuh, and cinematographer Jorg Schmidt-Reitwein; the time-lapse landscape shots as the clouds move over the mountains, from Heart of Glass (1976); the panning shots of Nosferatu's raft on the river, from Aguirre, Wrath of God (1972); the slowmotion depiction of the bat's flight, from The Great Ecstasy of the Woodsculptor Steiner (1974); the alienated protagonist and impotent bureaucrats, from The Mystery of Kasper Hauser (1974). By such varied means does the film continually inscribe presence/absence as a way of representing the spirit of the vampire.

Noël Carroll has questioned the significance of presence/absence as a paradigm for distinguishing film from other fictional narrative forms such as the novel or stage play. "Once we are considering the realm of fiction," Carroll writes, "it makes no sense to speak of the differences between cinema and theater in terms of what is absent to the spectator. In both fictional film and theatrical fiction, the characters are absent from the continuum of our world in the same way." Therefore, "Shylock is no more present to

the theater spectator than Fred C. Dobbs is present to the film viewer" (38). But Carroll's point holds true only for the referent—the reader's or viewer's mental construct of a character—and not for the signifier of that referent, in this case the actor. That is, Olivier is actually present on stage in the role of Shylock, while Bogart is not in the movie theater. The issue Metz and others have raised concerns not what the cinema signifies, but how . Moreover, the paradigm seems especially relevant to the reception of a remake, when the spectator remains continuously aware of the existence of a prior model that is both different and (except in the case of inserted footage, as in The Spirit of the Beehive ) absent from the present text.

In Nosferatu, the Vampyre, Herzog provides several occasions of presence/absence within the diegesis, discovering more subtle means for depicting a world of "lost objects" than Murnau's exploitation of stock effects such as negative shots and stop action. The film's arresting precredit sequence, with its slow tracking across the stricken faces of the mummified dead, begins the process of evoking the phantom existence that every film—but especially this film—brings to life. In addition to his relentlessly moving camera, Herzog employs an expressionist sound track—a mournful two-note chorus combined with the amplified sound of a heartbeat—to animate the still images, rendering them as "undead" through the particular signifying processes of the cinema. Similarly, the closing time-lapse shot of Harker riding off into the distance across a desert landscape accompanied by the choral strains of Gonoud's Sanctus confirms his new identity as a lost soul destined to wander endlessly in a "primordial elsewhere ." But the question of character remains: has his identity been permanently transformed by the vampire's bite, or simply revealed?

Another privileged moment that suggests the cinema's potential to represent the uncanny occurs when Harker seeks transport across the Borgo Pass to Dracula's castle. Herzog invents a dialogue scene missing from Murnau's film. While attending his four horses hitched to the stagecoach, the coachman replies to Jonathan's request for passage, "I haven't any coach." Asked if he will sell a horse for double the price, he answers, "Can you not see? I haven't any horses."[5] After walking alone for days across the mountains, Harker is finally rescued by the mysterious appearance of another coach, whose driver (as in both Murnau and Browning) disappears before they reach the castle. In a third permutation of what might be understood as a kind of reincarnation of Méliès's phantom hearse, the stricken Harker is driven back to Wismar in a single-horse rig whose perfectly balanced reflection Herzog mirrors in the adjacent canal. In each case, the imaginary calls into question, in effect remakes, the real.

In addition to such conventional devices as mirror shots and dramatic shadows, Herzog often employs formal composition within the frame to create the presence of absence, most clearly in the domestic scenes in

Figure 30.

The "Last Supper" in Herzog's Nosferatu, the Vampyre (1979), manages

to mix humor and horror in depicting the decay of civilized society.

Wismar after Harker's return. In one shot-in-depth, for example, Lucy reads about Dracula in close-up while her enervated husband can be glimpsed in the background slumped in a chair, now truly a lost object barely distinguishable from the furniture. A more subtle use of mise-enscène occurs earlier at the mountain inn. Harker impatiently demands his dinner so that he can be on his way to the count's castle. At the mention of Dracula's name, the gypsies all suddenly stop eating, and the composition becomes a virtual freeze-frame. In the foreground with his back to the camera, Jonathan confronts the silent, crowded room, with diners on either side of the frame and a triangular shadow in the middle ground pointing toward an empty window at the vanishing point. In this possible allusion to Renaissance paintings of the Last Supper, Herzog emphasizes not the presence of the Savior but the absence of communion: Jonathan remains estranged from both the innkeeper behind him (and the camera) and the guests before him; there is no chalice, no food, nothing in the window but a foreboding vacancy. Herzog follows this sequence with more obvious parodies of the Last Supper: first, when Jonathan dines with Dracula at the castle and later when the rats replace the bourgeois party consuming "their last supper" in the ruined town square. (See figure 30.)

These various phantom figures—the transmogrified mummies, the uncertain coaches, the debilitated husband, the empty window—all suggest a connection between the vampire's elusive existence and the cinema's presentation of character. As Nosferatu drains his victims of blood, the film image deprives its referent of the materiality it once possessed when it appeared before the camera. Every object, every actor becomes a ghost in the moment of projection, but no object seems as slippery, duplicitous, and evanescent as human character, which must remain both partially hidden (character as a signified, a matrix of emotional, moral and cognitive traits) and subject to change. Herzog, a filmmaker conversant with contemporary critical theory, compounds the spectator's awareness of this "lost object" status of film through a number of self-reflexive moments, some of which have already been described. The prominent mirror images, for example—Lucy's reflection in the water during her sleepwalking, the horizontal tracking shot of the coach returning Jonathan to Wismar, and the powerful scene when Dracula first visits Lucy as she sits before her dressing mirror—serve as reminders of the camera's mimetic function as well as the Lacanian basis ("the mirror stage") for Metz's theory of the cinema's imaginary signifier. Following Murnau's example in defying Stoker's conception of Dracula as casting no shadow, Herzog's Nosferatu is virtually defined by the darkness in which he lives and which he casts over others. In a brilliant stroke, Herzog displays only the count's shadow entering Lucy's bedroom and reflecting in her mirror, the door opening as if by itself; as he advances on her frightened form doubled in the glass, he casts no reflection of his own. Like Lucy, then, the spectator becomes terrified by the framed reflection of a shadow . What has been signified in this tableau, the irreducible nature of Dracula's character (he begs only to share Lucy's love), has been perfectly matched by the cinematic signifier.

At times, in fact, Nosferatu almost stands in for the cinema itself. In the memorable long shot of his phosphorescent skull glimmering in the darkened upper window of his Wismar mansion—a shot borrowed directly from Murnau—he resembles the light from the projection booth, casting his gaze on the community he holds in thrall. This association also occurs earlier at the castle when the count serves Harker a midnight supper. Dracula sits above and behind his visitor, his white bulb of a head surrounded by darkness and framed by a window, his labored breath like the sound of the projector mechanism, his attentive guest increasingly menaced by his mesmerizing presence. Judith Mayne has aptly described how Nosferatu here occupies "a literal 'no man's land'" (126) in the black background of the composition, the same uncharted region Harker himself will traverse in the film's concluding vision when he becomes, in effect, the remake of his master.

Perhaps the sanctification of the vampire's continuing mission as enun-

ciated in the finale by Gonoud's chorus should not be regarded as simply ironic. Like Herzog remaking Murnau, the new Nosferatu has not only escaped the quotidian realm that first oppressed him ("These canals that go nowhere but back on themselves," as Jonathan described Wismar) but also transcended his mentor's fate. No wonder, then, that Herzog seems to celebrate his disappearance into myth, to be reborn again as the phantom of the cinema.

Works Cited

Andrews, Nigel. "Dracula in Delft." American Film 4, no. 1 (1978): 32–38.

Barbow, John D. German Expressionist Film. Boston: Twayne, 1982.

Carroll, Noël. Mystifying Movies. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988.

Crabbe, Katharyn. "Lean's 'Oliver Twist': Novel to Film." Film Criticism 2, no. 1 (1977): 46–51.

Ellis, John. Visible Fictions. Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982.

Hake, Sabine. "Self-Referentiality in Early German Cinema." Cinema Journal 31, no. 3 (1992): 37–55.

Kawin, Bruce. "Nosferatu." Film Quarterly 33, no. 3. (1980): 45–47.

Mayne, Judith. "Herzog, Murnau, and the Vampire." The Films of Werner Herzog , edited by Timothy Corrigan, 119–32. New York: Methuen, 1986.

Metz, Christian. The Imaginary Signifier. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982.

Strick, Philip. "Nosferatu—the Vampyre." Sight and Sound 48, no. 2 (1979): 127–28.

Todd, Janet. "The Classic Vampire." The English Novel and the Movies , edited by Michael Klein and Gillian Parker, 197–210. New York: Ungar.