Thirteen—

Modernity and Postmaternity:

High Heels and Imitation of Life

Lucy Fischer

Remaking a Remake

Reappropriating existing representations . . . and putting them into new and ironic contexts is a typical form of postmodern . . . critique.

Linda Hutcheon, The Politics of Postmodernism

Pedro Almodovar's High Heels (Tacones Lejanos, 1991) is a work that might be placed within the emerging genre of "postmodern" film. In fact, a review of it by Roger Ebert notes how "the writers of New York weeklies" regularly link that term to the film's director. As Linda Hutcheon makes clear, one of the hallmarks of the postmodern aesthetic is its radical intertextuality—its tendency to quote and recycle tropes and thematics from the discursive past.

Almodovar has acknowledged this inclination. He has deemed himself a creative "mirror with a thousand faces" that "reflect[s] everything around [him]" (Morgan, 28). While admitting a penchant for homage, he notes his citations are not the "tributes of a cinephile." Rather, they arise "in a lively and active way" as organic features of the text (Morgan, 28).

It is within this framework that we might envision High Heels as a remake of Douglas Sirk's canonical film, Imitation of Life (1959). Many have recognized Sirk's influence on Almodovar's style. The latter bemoans the devaluation of melodrama and calls Sirk a "genius" (Morgan, 29). To characterize Almodovar's theatrical mode, Roger Ebert deems it "inspired" by Sirk (44). Dave Kehr sees, in the Spaniard's "bold, ironic use of color," a tribute to the Hollywood legend (F7).

Clearly, however, there are specific aspects of High Heels that solicit a comparison to Imitation of Life .[1] Both films take a female performer as their heroine. Imitation traces a decade in the life of Lora Meredith (Lana

Turner), and aspiring actress who eventually achieves success on Broadway and the silver screen. High Heels follows the character of Becky Del Paramo (Marisa Paredes), a singer who is already a star when the narrative begins. In both cases, the protagonist has a tense and troublesome relationship with her daughter. In Imitation, Susie (Sandra Dee) accuses Lora of parental neglect and becomes enamored of her mother's lover—a circumstance that brings the women's conflict to a head. In High Heels, Rebecca (Victoria Abril) similarly accuses Becky and marries (then murders) her mother's former lover, Manuel.

In both texts, there is a subplot involving another parent-child dyad. In Imitation, it involves the family of Lora's maid, Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore). In High Heels, it concerns the menage of Judge Dominguez (Miguel Bose), the man investigating Manuel's homicide.[2] In both cases, the child involved in the subplot is a performer whose vocational choice mocks that of the heroine. In Imitation, Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner) becomes a burlesque dancer; in High Heels, Dominguez goes "under cover" as a female impersonator. In both instances, the parent in the subplot is involved with the star performer. In Imitation, Annie serves as Lora's backstage confidante and dresser. And in High Heels, Senora Dominguez keeps a fan album of clippings on Becky's career.

At times, the parallel between the films is even tighter. Both open with sequences involving a beach locale and a lost child. In Imitation, Lora frantically searches a Coney Island boardwalk for Susie, who has disappeared. In High Heels, as Rebecca awaits the arrival of her mother's airplane, she recalls running away as a youth during a seaside vacation. Both films end in heart-wrenching deathbed scenes. In Imitation it is that of the black domestic; in High Heels it is that of the heroine.

High Heels' status as a remake is made more complex by the intricate "genetics" of Imitation . Originally written by Fannie Hurst in 1932 as a piece of serialized magazine fiction, it was published as a book in 1933. It was first adapted for the screen by John Stahl in 1934, then later refashioned by Sirk. Hence, High Heels constitutes a remake of a remake, a copy of a copy, an imitation of an Imitation . (See figure 24.)

A Postmodern Simulacrum

Rather than a mere expression of nostalgia, postmodernism may be seen as an attempt to recover the morphological continuity of specific culture. The use of past styles in this case is motivated not by a simple escapism, but by a desire to understand our culture and ourselves as products of previous codings.

James Collins, "Postmodernism and Cultural Practice"

Aside from its citation of Imitation, there are other reasons why Almodovar's film constitutes a postmodern remake. Its intertextual vision is highly parodic—filled with (which Hutcheon has termed) "self-conscious, self-contradictory, self-undermining statement" (1). In the Sirk film, melodramatic moments often border on comedy (as when the telephone rings for Lora with a job offer each time she is about to kiss her lover, Steve [John Gavin]). This nascent farce (just below the histrionic facade) was apparent to Rainer Werner Fassbinder—whose films were also modeled on Sirk's. Here is an excerpt from Fassbinder's tongue-in-cheek summary of Imitation (which he calls a "great, crazy movie about life and death . . . [a]nd . . . America"): "[The characters] are always making plans for happiness, for tenderness, and then the phone rings, a new part and Lana revives. The woman is a hopeless case. So is John Gavin. He should have caught on pretty soon that it won't work" (Fischer, 1991A, 244–45).

In High Heels the ironic and melodramatic modes are nearly indistinguishable. When Becky and Rebecca are first reunited, they embrace. At that heightened instant, Rebecca's earring becomes caught in Becky's hair. When Judge Dominguez asks Becky whether she has killed Manuel, she replies, "You don't do that before an [theatrical] opening." Later, as Becky is taken away in an ambulance, she tells her homicidal daughter, "Find another way to solve your problems with men."

Beyond its conjuration of Imitation, the film's cinematic references are quite extensive. With Almodovar's focus on maternal melodrama, there are intimations of Mildred Pierce (1945). That film also depicts an incestuous triangle in which a daughter kills her mother's lover. Like Becky, Mildred attempts to assume responsibility for her offspring's crime. (Interestingly, Roger Ebert sees the performance of Marisa Paredes in High Heels as "inspired . . . [or inhabited by] Joan Crawford" [44]). While Mildred Pierce is never mentioned in almodovar's film, Ingmar Bergman's Autumn Sonata (1978) is. That film (which concerns a woman's struggle with her renowned pianist-mother) is cited by Rebecca to explain how she is plagued by Becky's fame. Other quotations issue from Dominguez's pose as a female. As he sings in a nightclub, members of the audience duplicate his every gesture (like spectators of The Rocky Horror Picture Show [1975]). When Dominguez confesses his love to Rebecca and she rebuffs him for cross-dressing, he replies, "Nobody's perfect." That line replicates one spoken by Osgood (Joe E. Brown) in Some Like it Hot (1959) when he learns that the woman he adores is a man.

While High Heels circulates in elitist film markets, its citations often derive from mass culture—a fact that distinguishes postmodernist from modernist works. As Almodovar, himself, has stated: "I think you can look at genre . . . without making those 'exquisite' divisions of art cin-

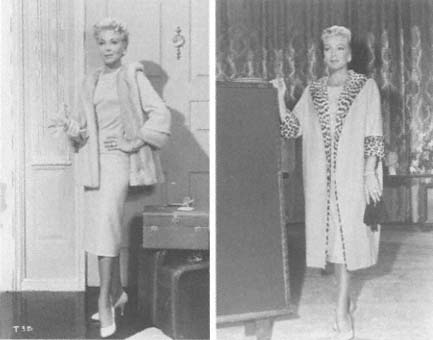

Figure 24.

Lana Turner struts her stylish stuff in Douglas Sirk's Imitation of Life (1959),

a remake of the 1934 version with Claudette Colbert.

ema [and] popular cinema" (Morgan, 28). That his quotations are often from American movies, testifies to the hegemony of Hollywood film in the world economy, as well as to America's more "egalitarian" vision of the arts.[3]

Aside from deconstructing the binaries of high and low culture, the postmodern work has been said to relax the boundaries between fact and fiction. Hutcheon sees the form as enacting a process of hybridization "where the borders are kept clear, even if they are frequently crossed" (37). High Heels slyly suggests the "real" in its invocation of a controversy that surrounded the making of Imitation: the fatal stabbing of Lana Turner's lover by her daughter, Cheryl Crane, in April of 1958 (Fischer, 1991A, 216–18). In High Heels, this fact reenters (with a vengeance) in Rebecca's twin murders: her childhood killing of her stepfather (by switching his medications) and her later shooting of Manuel.[4] While this subtext can be excavated from Imitation, it is on the surface in High Heels, which makes crime the central axis of the drama (Fischer, 1991A, 21–8). Thus, High Heels par-

takes in a dual homage: to the fictional narrative of Sirk's film and to the documented tragedy of Turner and Crane. As though to suggest the infamous 1958 tabloid expose, Almodovar makes Rebecca a newscaster who confesses her offense during a broadcast. He also has Becky write her memoirs, a fact that alludes to the autobiographies penned by Turner and Crane. If Marisa Paredes reminds us of Joan Crawford, thoughts of Mommie Dearest (1981) cannot be far behind.

While High Heels accesses the "real" of a Hollywood scandal, it relinquishes the theme of race so prominent in Imitation, figuring it only in a flashback of the "natives" who populate the island of Rebecca's childhood vacation. If "passing" is at issue in the film, it is devoid of racial overtones and attends to Judge Dominguez and his feminine disguise.[5]

As High Heels intermingles fact and fiction, so it crosses genres—much as Judge Dominguez crosses dress. (Almodovar himself states that he does not "respect the boundaries of . . . genre" but "mix[es] it with other things" [Kinder, 1987, 38]). Hence, High Heels is a "hybrid" of the melodramatic, satirical, and film noir modes. The film's myriad references to cinema, publishing, and television tap into another postmodern theme: the overwhelming presence of media within contemporary culture—producing a vision of existence as the transmission of synthetic images. For Jean Baudrillard, we live in an age in which "production and consumption" have given way to "networks" through which we experience an "ecstasy of communication" (1983, 127). Significantly, the life dramas in Almodovar's film are enacted on TV. Manuel is a network executive. Not only does Rebecca break down during a televised program but her mother and Judge Dominguez learn of her wrongdoing by watching the show. Likewise, it is by viewing TV that Rebecca discerns her mother is ill. Finally, a narrative twist arises when Rebecca claims the wrong set of prints from a photographic lab—as though to symbolize the rampant confusion of images in the world. Clearly, the issue of artificiality is already apparent in Imitation, whose title and theatrical setting unavoidably elicit the theme (Affron, Stern).

Other aspects of High Heels reveal a postmodern bent. At times, the drama suffers "lapses" at odds with its overall continuity. (David Kehr, for example, complains of the film's "strange displacements.") When Rebecca is jailed and sent to the prison courtyard, several inmates enact a bizarre, choreographed "production number" reminiscent of those in a Hollywood musical. On another occasion, when Rebecca reads the television news, she laughs as she reports the weekend traffic fatalities (as though to reference Jean-Luc Godard's Weekend [1968]). In both cases, the diegesis is ruptured through homage. At other times, the slippage is produced by an excess of emotion rather than by an ironic gap. As Becky sings in a theater (distraught over Rebecca's incarceration), she kisses the stage floor, whereupon a tear drop falls and lands on her bright red lip print. It is an unlikely

moment that functions as a pure icon of sentimentality (like a bird on a branch in a D. W. Griffith film).

"Sign Crimes against the Big Signifier of Sex"

Nothing is less certain today than sex.

Jean Baudrillard, Seduction

Perhaps, the most postmodern aspect of High Heels is its presentation of gender. Postmodernism has been known for its decentered and negotiable engagement of subjectivity: both that of its dramatis personae and of its audience. (As Hutcheon explains, subjectivity "is represented as something in process" [39]). Privileged in this regard is the genre's depiction of sexuality. According to Arthur Kroker and David Cook, a "reversible and mutable language of sexual difference" is a yardstick of postmodern discourse (20). Elsewhere, they describe the postmodern creator as "committing sign crimes against the big signifier of Sex" (21).

In High Heels, this authorial "larceny" (which duplicates Rebecca's) arises in a variety of ways. Clearly, one of the most transgressive aspects of the narrative is the figure of Judge Dominguez who allegedly goes "under cover" as "Femme Lethal" (a female impersonator), in order to solve the case of a transvestite's murder. (As Barbara Creed has noted, the androgyne is a signal figure in today's mass culture [65]). While we assume that Rebecca knows that Lethal is a man when she follows him into his dressing room, she seems shocked as he disrobes—perhaps, because he has a mole on his penis. While the two become amorous, he does not use his genitals for their erotic caper. Rather, in a more gender-neutral manner, he performs cunnilingus as she hangs from the rafters. What is not revealed at this time is that Lethal is Judge Dominguez (though an astute viewer can surmise it). But when this is disclosed, along with his professional rationale for cross-dressing, we are not convinced that it "explains" his behavior. Rather, we suspect that his real reasons are "under cover" too. Perhaps, he is not (what Chris Straayer would term) a "temporary transvestite," but one with a more permanent commitment [36]). Recalling the parallel subplots of Imitation and High Heels, we are reminded that Dominguez "stands in" for Sarah Jane—also a nightclub performer—thus, accomplishing yet another gender crossing.

To make this issue more slippery, there is a second sexually enigmatic character in the film. When Rebecca is jailed, she meets Chon, an inmate who seems atypically large for a woman. One considers whether she is a male in drag, but rejects this theory due to her exposed, prominent, (and seemingly "natural") breasts. Evidently, however, for the Spanish audience the situation is less perplexing. Chon is played by a notorious Spanish trans-

sexual, Bibi Andersson—ostensibly named for the Swedish movie star (Morgan, 29). (Curiously, while writing this paper, I happened upon an edition of The Maury Povich Show entirely dedicated to the plight of imprisoned transsexuals—which indicates that the situation goes beyond one of Almodovar's campy plot devices.)[6]

The question of gender instability seems encapsulated in an exchange within the film. When Manuel asks Lethal if he is male or female, the latter replies, "For you, I'm a man." Clearly, Lethal's drag performance highlights another element within postmodern discourse—a penchant for the carnivalesque. For Brian McHale, "[P]ostmodernist fiction has reconstituted both the formal and the topical . . . repertoires of carnivalized literature" (173).

In all these cases, the notion of gender is presented as something flexible rather than fixed; it is one more Truth that postmodernism can dismantle. And the cinema is especially adept at executing such a masquerade. For, as Parker Tyler once noted, "With its trick faculties and gracile arts of transformation, the film's technical nature makes it the ideal medium for penetrating a mask, physical or social, and thus for illustrating once more that . . . things are not always what they seem" (210).

For Almodovar, however, the nature of Dominguez's protean sexuality has broader political ramifications: "[F] or me, there is ambiguity in justice and that's why I have given it to the character of the judge. I don't know what the face of justice is—sometimes it's masculine, sometimes it's feminine" (Morgan, 29). Curiously, in his last remark, Almodovar implies that masculinity and femininity exist as static and oppositional poles—rather than as the fluid continuum the film seems to imagine.

Beyond remaking a man as a woman, High Heels' postmodernist remake casts Lethal as counterfeiting the theatrical persona of Becky. It is her appearance he conjures at the cabaret, and her signature musical number that he performs. He later even apologizes to her for his "imitation." This plot device has numerous connotations. It foregrounds the power of the female star as a "role model" not only for women but for men. Specifically, it invokes the gay camp mimicry of such figures as Judy Garland, Barbra Streisand, Cher, Mae West, Joan Crawford, and Lana Turner. For, as Rebecca Bell-Mettereau has noted, "The homosexual impersonator's desire is to imitate a woman of power and prestige, a professional performer rather than a 'real woman'" (5). Lethal's simulation also reveals what many theorists have observed about "femininity" within patriarchal culture: that it requires a masquerade even of biological women—a performance not all that different from drag (Doane, 1990; Johnston). Judith Butler, in fact, sees the engagement of gender as requiring a failed imitation of an elusive prototype: "[T]he repetitive practice of gender . . . can be understood as the vain and persistent conjuring and displacement of an idealized original, one which

Figure 25.

Ana Lizaran, Marisa Paredes, and Victoria Abril star in Pedro Almodovar's

hilarious and timely Spanish update of Imitation of Life (1959), High Heels (1991).

no one at any time has been able to approximate" (2). Significantly, she sees the narrative of Imitation as exemplifying this process, through its focus on the hyperfemale, Lora Meredith.

But the more intriguing element of Lethal's approximation of Becky is that it places him within the maternal position: after all, it is Rebecca's mother whom he ends up "being." Rebecca even acknowledges this. When she encounters a poster for Lethal on the street (see figure 25), she tells Becky that she had gone to see him when she missed her. Thus, in reproducing himself as a female, Dominguez also becomes the human capable of corporeal reproduction: woman. This facsimile of motherhood becomes more resonant when one recalls that, earlier in the film, Rebecca had accused Becky of merely "acting" her parental role—a charge also issued by Susie to Lora in Imitation .[7]

But what are the implications of this narrative move, as regards the film's overall sexual politics? Typical of postmodernism, a multiplicity of readings and subject positions are offered to us. On one level, the device seems to raise questions about the relationship between a heterosexual woman's adult desire for a man and her infantile love for her mother. According to the prescribed psychiatric script, if a girl is to become heterosexual, she must "shift" her affection from her mother to a male. While in the

traditional literature, this turnabout is likened to a substitution, recent views have cast it as a supplementation. While the girl does not relinquish her affection for her mother, she "widens" it to allow for a man. As Nancy Chodorow observes, "[A] girl develops important Oedipal attachments to her mother as well as to her father" (127). The drama of High Heels enacts this move by cementing mother and lover in Dominguez (a man attached to his own mother).

It further complicates this odd arrangement by implying that Dominguez may be gay (given his penchant for drag, and his mother's mention of AIDS). That he chooses a female love object (in Rebecca) is not entirely incompatible with that reading. For, as Kaja Silverman has remarked (in paraphrasing Marcel Proust), "[T]here are two broad categories of homosexuals—those who can love only men, and those who can love lesbian women as well as men" as both occupy a same-sex "feminine psychic position" (381). Interestingly, such homosexuals identify strongly with their mothers—enclosing "a woman's soul . . . in a man's body" (Silverman, 339–88). For Lethal, that soul spills over onto his exterior, in the form of his female attire. Within this framework, Rebecca is a repressed lesbian—a woman who can only want a man who appears to be a woman—the primal woman at that. For Marsha Kinder, Rebecca's conduited maternal desire is liberatory: "This film . . . boldly proclaims that mother love lies at the heart of all melodrama and its erotic excess" (1992, 40).

The film further investigates the problematic rapport between mother and daughter. If Rebecca is haunted by a nostalgia for the Imaginary, so is Becky (whose signature torch song is entitled "You'll Recall "). She returns to Madrid specifically to acquire the basement flat in which she was raised. At the end of the film the two women's regressions merge. As Becky lies in her childhood apartment dying, Rebecca pulls the curtains of the high window that faces the street above. As pedestrians stroll by, she watches their legs and feet. She remembers how, as a child, when Becky went out, she would anxiously await the sound of her mother's high-heeled footsteps returning (hence, the literal title of the film: Distant Heels ).

Though this scene is poignant, it is undercut by earlier parodic moments of the film. Within the context of the myriad "perversions" the text invokes (patricide, transvestitism, incest), the notion of foot fetishism unavoidably comes to mind—a syndrome signaled in the work's title. For Freud, this symptomology is tied to the young boy's shock at seeing his mother's lack of a penis. As Freud notes, "[W]hat is possibly the last impression received before the uncanny traumatic one is preserved as a fetish. Thus the foot or shoe owes its attraction as a fetish . . . to the circumstance that the inquisitive boy used to peer up the woman's legs towards her genitals" (217). In High Heels , Lethal's platform shoes are very visible in his cabaret number—an act that imagines a mother with a penis. And, when he and Rebecca

make love in his dressing room, she is afraid to jump from the rafters because she is wearing high heels. These ironic moments (involving shoes) "infect" the denouement, giving Rebecca's yearning for her mother's footsteps a masculine and "unnatural" cast. Significantly, she looks up, from a basement window, at people walking by on the street—as though to literalize Freud's vision of the male fetishist-to-be, gazing up women's skirts.

Given Becky's desire to return home, Rebecca's melancholy and nostalgic angst seem a remake of her parent's—adding to the problematic tendentious portrayal of mother-daughter symbiosis. But Rebecca is a replicant on more levels than one. Her name seems a variant of her mother's: hence "Re-Becca" remakes "Becky." She marries her mother's former lover and then considers wedding her mother's male doppelgänger. Furthermore, during the course of the film, Rebecca becomes pregnant (by her maternal look-alike), thus approaching the matrilineal position herself. Hence, within the film, "the reproduction of mothering" goes berserk. But its vertiginous chain of duplication should not surprise us, for, as Hutcheon notes, "commitment to doubleness or duplicity" is a benchmark of postmodernism. High Heels engages this trope both within the style and thematics of the film: it is a remake about the process of remaking.

Polymorphous Perverse

The postfeminist play with gender in which differences are elided can easily lead us back into our "pregendered" past where there was only the universal subject—man.

Tania Modleski, Feminism Without Women

While the mutable world of postmodernism has been applauded in some critical circles and heralded for its progressive thrust (Hutcheon, 141–68), in other arenas it has been treated with suspicion. Feminists have been loathe to relinquish the category of "woman" for fear that the act subverts their analysis of patriarchal culture. E. Ann Kaplan notes that "much of what people celebrate as liberating in . . . postmodernism is . . . an attempt to sidestep the task of working through the constraining binary oppositions, including sexual difference" (43). And Barbara Creed observes that the "postmodern fascination with the . . . 'neuter' subject may indicate a desire not to address problems associated with the specificities of the oppressive gender roles of patriarchal society, particularly those constructed for women" (66).[8]

It is clear how this debate might inform the case of High Heels . It is a film that, no doubt, entails gender fluidity, but (we might inquire) fluidity for whom? Ultimately, it is man who has that prerogative, not woman. Almodovar can dabble in the "woman's picture." Dominguez can imitate a

female. And Chon can "become" one. The only hint of movement in the opposite direction is the androgynous demeanor of Marisa Paredes as Becky. But what she resembles is not so much a man, as a man impersonating a woman—like Dominguez as Lethal. Hence, what passes for difference is, ultimately, the same—like Luce Irigaray's notion of the Freudian "Dream of Symmetry."[9] B. Ruby Rich makes a similar point in her observations on postmodernism: "In all the talk about transvestitism and transsexualism there's little acknowledgment that even the world of gender-bending is male dominated—it's just that here men rule in the guise of women" (73).

There is also a fetishistic strain to High Heels that works against the film's claims for an unconventional vision of sexuality (despite Kinder's deeming such fetishism "fetching" [1992, 41]). Aside from shoes, the theme privileges the prop of earrings: pendulous objects seen to hang from a women's body, as though in "compensation" for that which does not . In the opening scene of the film, as Rebecca awaits Becky's arrival, she remembers that her mother bought her earrings on a childhood trip. We learn that they were made of horn—a substance associated with male animals. It is this jewelry that Rebecca fondles and wears on the day of her mother's return—that gets tangled in Becky's hair. Later, when Rebecca takes her mother to the nightclub, Lethal and Becky exchange mementos: she donates one of her earrings (a stand-in for the lost penis) and he offers one of his "tits." In the later scene of Becky performing on stage, she wears huge, dangling earrings that graze her shoulders. In all these cases, Becky seems linked to a fetishistic object that "substitutes" for the male genitalia. This bespeaks a masculine view of woman as signifying a distressing, physiological "lack." Only a man like Dominguez (in drag) can constitute a woman who is "fully equipped."

Rebecca, too, seems haunted by a phallic lack, which is overcome by her appropriation of a gun (a familiar symbol). In the film's opening credits, drawings of high heels and guns are juxtaposed—linking the two fetishistic items. Furthermore, a Sight and Sound cover (announcing a review of High Heels inside) reads "Almodovar's Stiletto Heels"—again coupling shoes with a phallic weapon (this time a knife). Significantly, Rebecca hides the gun in the chair in which Manuel used to sit—emphasizing the physical and semiotic proximity of the firearm and the phallus. It is this gun that she delivers to the dying Becky, so that her mother might mark it with her own fingerprints and false guilt.

In forcing the gun on Becky, she turns the latter into the archetypal Phallic Mother—a classic figment of the male child's imagination. Sigmund Freud referred to this fantasy in 1928, while discussing the fetishist's inability to accept his mother's genital "omission." But, in discussing this phenomenon, Freud implies that the fabrication is present in normal masculine development. As he notes, "[T]he fetish is a substitute of the . . . (mother's)

phallus which the little boy once believed in and does not wish to forego" (215). Thus, Rebecca is placed in the position of a "transvestite" daughter—whose psychic essence is male. Obviously, she finds the ultimate Phallic Mother in Lethal and his masquerade as Becky.

Clearly, this fantasy is equally powerful for Dominguez, who, in his role as cross-dresser, makes a similar maternal disavowal (Kulish, 394). His problematic relation to his own bedridden mother surfaces in scenes in which he is depicted in her home. The narrative context is unclear, but it is entirely possible that they still live together.

But need the fetishistic drift of the film be read as masculine? While some feminists have raised the possibility of female fetishism, it bears a different cast than the male variety. In an article on lesbianism, Elizabeth A. Grosz makes the point that, rather than disavowing the "castration" of their mothers, young girls may deny their own (47). It is this disavowal that is translated into female fetishism. The "narcissistic" woman may compensate for her own perceived "lack" by vainly making a fetish object of herself (through excessive costume, makeup, jewelry, etc.). The "hysterical" woman will compensate by selecting a part of her body for fetishistic "disabling" (e.g., paralysis). The "masculine" woman will dissociate herself from femininity by seeking out women with whom she can act "like a man" (47–52). None of these cases of alleged female fetishism are dominant in High Heels —where women are linked to phallic objects—a configuration more closely tied to men.

Significantly, we find the same male bias in the writing of a critic who pioneered discussions of transvestitism and film: Parker Tyler. In Screening the Sexes , he sees male cross-dressing as replicating the symbolism of sexual intercourse, which he describes from a masculine perspective: "When, with the surrogate of his penis, a man penetrates a woman, he wears her body . The penis dons the vagina via the vulva and wears the womb as a headdress. . . . In dynamic terms a curious kind of transsexuality has taken place" (217).

Hence, male cross-dressing is appropriate, as he already "wears [a woman's] body" (like some hatted Ziegfeld girl) in coitus. (In the world of the 1990s, the notion of a man "wearing" woman's body has disturbing associations to The Silence of the Lambs [1991]). When Tyler talks of conception, his metaphors are somewhat modified: "In 'planting the tree' of his body, the male transplants it . . . duplicates his own penis in the opposite direction. . . . [T]he woman, as the penetrated one, herself senses this exchange of penis orientation as a transference, or 'transvestitism.' Hence at the crux of the act of potency, she becomes the penised one and, as such, one who wears, has donned her own vagina" (217–18).

Thus, it is only through access to man's penis that the woman can "wear" her own organs—which are, otherwise, worn by him.

In many ways, High Heels replicates Parker's scenario. It is Dominguez

who makes love to and "wears" Rebecca's vagina in the dressing room of the club in which he cross-dresses. It is he who will later implant his "tree" and "seed" in her—thus, "permitting" her to wear her own sexuality.

Postmaternity

The writer is someone who plays with his mother's body . . . in order to glorify it, to embellish it, or in order to dismember it.

Roland Barthes, quoted in Susan Suleiman, Subversive Intent

Clearly, High Heels remakes Imitation and the star scandal surrounding it. But how does it reproduce motherhood? Elsewhere, I have shown how the Sirk film charts the impossibility of female parenting: if Lora is damned as uncaring, Annie is guilty of overprotecting; if Lora is faulted for putting profession before home, Annie is chastened for making a career of domesticity. While the narrative begins by establishing Annie and Lora as good versus bad mothers, it ends by equalizing them in failure (Fischer, 1991A, 14–21). Whenever the women have troubles with their daughters, Steve steps in. When Lora departs on a film shoot, Steve is left in charge of entertaining Susie. When Annie wishes to pursue Sarah Jane, Steve makes the travel arrangements. "It's so nice to have a man around the house . . ."

While this masculine takeover is subtle in Imitation , it is strident in High Heels , which adopts (what we might deem) a "postfemale" stance. Clearly, this position requires the figure of Dominguez—a man who imitates and supplants a woman. Jean Baudrillard has argued that "[t]he strength of the feminine is that of seduction " (1990, 7, my italics). This act is based on "artifice" and stands in opposition to the masculine reality principle. As he writes, "The only thing truly at stake" in seduction "is mastery of the strategy of appearances, against the force of being" (1990, 10). If femininity is associated with surface (as distinct from masculine "depth"), it follows that the female body holds no particular truth or weight. As Baudrillard states, seduction knows "that there is no anatomy . . . that all signs are reversible" (1990, 10). According to this logic, the transvestite (like Lethal) becomes the ultimate "woman" because of his exaggerated play with the codes of femininity: "What transvestites love is this game of signs, . . . with them everything is makeup, theater, and seduction" (1990, 12–13). While championing this mimicry, Baudrillard admits that it may bear a critical tone: "The seduction . . . is coupled with a parody in which an implacable hostility to the feminine shows through and which might be interpreted as a male appropriation of the panoply of female allurements" (1990, 14). In High Heels , this translates into a cruel joke on the negation of anatomy as destiny.

Beyond valorizing a postfemale world, High Heels offers a "post-maternal "

one—envisioning a universe in which men (like Dominguez) make the best Moms (as Tootsie once made the best feminist). For, it is he who functions as maternal hero(ine) or surrogate mom—a role vacated by Becky through her parental ineptitude. It is he who loves and comforts the hysterical Rebecca, who arranges for a rapprochement within her family, who finesses her release from jail, who bares the maternal "breast" (albeit a "falsie"). Meanwhile, all that Becky manages is to reproduce her neuroses in her daughter and to visit her maternal sins upon her child.

Hence what we find in High Heels is the kind of questionable "male mothering" so prevalent in contemporary cinema—a phenomenon that I have critiqued elsewhere (Fischer, 1991B).[10] While, superficially, this trope seems to express a benign male nurturant impulse—it arises at the expense of woman—causing her to feel a monumental postpartum depression.

In writing on the film, Kinder notes that Almodovar's project began as a narrative about two sisters who kill their mother. In Kinder's interview with him, Almodovar claims that "[w]hen you kill the mother, you kill precisely everything you hate, all of those burdens that hang over you" [1987, 43]). While Kinder admits the misogyny of Almodovar's abandoned scenario, she sees the final film as an "inversion" of that paradigm, in which "the . . . goal [is] no longer to destroy the maternal but . . . to . . . empower it" (1992, 39). Elsewhere, I have used the term "matricide" for the male diegetic appropriation of maternal space ("Sometimes"). Unlike Kinder, I find it applicable to the fate of Becky in High Heels —a fate that indicates a return to Almodovar's original theme. For, Becky's demise seems linked as much to Lethal's "voodoo" replacement of her as to Rebecca's heinous behavior. As Baudrillard observes, "To seduce is to die as reality and reconstitute oneself as illusion" (1990, 69). As Becky expires, Lethal triumphs as the seductive maternal imago.

In cataloging various attacks on postmodernism, Hutcheon notes that its contradictory and multifarious discourse has been found "empty at the center " by critics who decry the vacuity of its myriad interpretive scenarios (38).[11] This image of the void might well apply to Dominguez—who can emulate the maternal surface but never be "fully equipped" at the maternal core or corps. It might also to apply to Almodovar, who "empties" Imitation of its maternal weight.

Curiously, for Baudrillard, it is masculinity that is aligned with "production" and femininity with its absence: "All that is produced, be it the production of woman as female, falls within the register of masculine power. The only and irresistible power of femininity is the inverse power of seduction" (1990, 15).

What this vision accomplishes is to deny any mode of female agency. It negates production as maternal reproduction —once again declaring woman's

body null and void. Furthermore, it deems man (like Adam) the creator of "woman as female"—leaving her entirely out of the semiological and biological loop.

One suspects that Almodovar chose the name "Femme Lethal" to highlight the cultural cliché of the femme fatale. (Since High Heels invokes film noir, this archetype is especially apt.)[12] According to Mary Ann Doane, the stereotype arose with the Industrial Revolution—at "the moment when the male seems to lose access to the body which the woman then comes to overrepresent " (1991, 2). By 1991, however, the female is underrepresented, and her being subsumed by the allegedly "disembodied" male. For Doane, the femme fatale is "the antithesis of the maternal—sterile or barren, . . . produc[ing] nothing in a society which fetishizes production" (1991, 2). In this sense, the figure finds her true incarnation in the corpus manquée of Lethal. Hence, while Almodovar (in feminist drag) may have meant to mock female stereotypes with the name "Femme Lethal," we can also read his epithet "against the grain." Perhaps it reveals that the postmodern posture may be "lethal" to the women who deem it progressive, who are "seduced" by it. Doane wisely remains skeptical of the femme fatale as a "resistant" figure: "[I]t would be a mistake to see her as some kind of heroine of modernity. She is not the subject of feminism but a symptom of male fears about feminism" (1991, 2–3).

Elaine Showalter once observed that "[a]cting as a woman . . . is not always a tribute to the feminine" (138). Ultimately, what is "under cover" in High Heels is not only a male judge but a male judgment latent in the euphoric "polymorphous perversity" of the postmodern pose.

Works Cited

Affron, Charles. "Performing Performing: Irony and Affect." In Fischer, Imitation of Life,: 207–15.

Barthes, Roland. The Pleasure of the Text. Translated by Richard Miller. New York: Hill and Wang, 1975.

Baudrillard, Jean. "The Ecstasy of Communication." In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. by Hal Foster. Port Townsend, Washington: Bay Press, 1983: 125–134.

———. Seduction. Translated by Brian Singer. N.p.: Editions Galilée, 1979; New York: St. Martin's, 1990.

Bell-Mettereau, Rebecca. Hollywood Androgyny. New York: Columbia, 1985.

Butler, Judith. "Lana's 'Imitation': Melodramatic Repetition and the Gender Performative." Genders, no. 9 (fall 1990): 1–18.

Chodorow, Nancy. The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1978.

Collins, James. "Postmodernism and Cultural Practice." Screen 28, no. 2 (spring 1987): 11–26.

Creed, Barbara. "From Here to Modernity: Feminism and Postmodernism." Screen 28, no. 2 (spring 1987): 47–67.

Doane, Mary Ann. Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory and Psychoanalysis. New York: Routledge, 1991.

———. "Film and the Masquerade: Theorizing the Female Spectator." In Issues in Feminist Film Criticism, edited by Patricia Erens, 41–57. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

Ebert, Roger. "Story Looks Stylish in High Heels. " Chicago Sun Times, 20 December 1991, p. 44.

Fassbinder, Rainer Werner. "Six Films by Douglas Sirk." Translated by Thomas Elsaessar. Excerpted in Fischer, Imitation of Life, 244–249.

Fischer, Lucy, ed. Imitation of Life. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1991.

———. "'Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child': Comedy and Matricide." In Comedy, Cinema, Theory, edited by Andrew S. Horton, 60–78. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1991.

Freud, Sigmund. "Fetishism." In Sexuality and the Psychology of Love, edited by Philip Rieff, 214–9. New York: Colliers, 1974.

Grosz, Elizabeth A. "Lesbian Fetishism?" differences 3, no. 2 (summer 1991): 39–54.

Hurst, Fannie. Imitation of Life. New York: Collier and Son, 1933.

Hutcheon, Linda. The Politics of Postmodernism. New York: Routledge, 1989.

Irigaray, Luce. Speculum of the Other Woman. Translated by Gillian C. Gill. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 11–240.

Johnston, Claire. "Femininity and the Masquerade: Anne of the Indies ." In Psychoanalysis and Cinema, edited by E. Ann Kaplan, 64–72. New York: Routledge, 1990.

Kaplan, E. Ann, ed. Postmodernism and its Discontents. London: Verso, 1988.

Kehr, David. "Almodovar Takes a Melodramatic Turn in High Heels ." Chicago Tribune, 20 December 1991, p. F7.

Kinder, Marsha. "High Heels. " Film Quarterly 45, no. 3 (spring 1992): 39–44.

———. "Pleasure and the New Spanish Mentality: A Conversation with Pedro Almodovar." Film Quarterly 41, no. 1 (fall 1987): 33–44.

Kroker, Arthur, and David Cook. The Postmodern Scene: Excremental Culture and Hyper-Aesthetics. New York: St. Martin's, 1986.

Kulish, Nancy Mann. "Gender and Transference: The Screen of the Phallic Mother." International Review of Psychoanalysis 13 (1986): 393–404.

McHale, Brian. Postmodernist Fiction. New York: Methuen, 1987.

Modleski, Tania. Feminism without Women: Culture and Criticism in a 'Postmodernist' Age. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Morgan, Rikki. "Dressed to Kill." Sight and Sound 1, no. 12 (1992): 28–9.

Rich, B. Ruby. "Gender Bending." Mirabella, December 1992, 71–75.

Showalter, Elaine. "Critical Cross-Dressing and the Woman of the Year." Raritan (fall 1983): 130–49.

Silverman, Kaja. Male Subjectivity at the Margins. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Stern, Michael. "Imitation of Life. " In Fischer (1991): 279–88.

Straayer, Chris. "Redressing the 'Natural': The Temporary Transvestite Film." Wide Angle 14, no. 1 (1992): 36–55.

Straub, Kristina. "Feminist Politics and Postmodernist Style." In Image and Ideology in Modern/Postmodern Discourse, edited by David B. Downing and Susan Bazargan, 273–86. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991.

Suleiman, Susan. Subversive Intent: Gender, Politics, and the Avant-Garde. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Thompson, David. "High Heels. " Sight and Sound 1, no. 12 (1992): 61–2.

Tyler, Parker. Screening the Sexes: Homosexuality in the Movies. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1972.