Eleven—

Cinematic Makeovers and Cultural Border Crossings:

Kusturica's Time of the Gypsies and Coppola's Godfather and Godfather II

Andrew Horton

I think that the concept of border suggests something very subversive and unsettling. . . . [I]t means recognizing the multiple nature of our own identities.

Henry A. Giroux, Disturbing Pleasures

Dedicated to Gypsies, filmakers, and border crossers everywhere.

"Yes, this is a Gypsy Godfather, " wrote the Time reviewer Richard Corliss in 1990 when Time of the Gypsies, by the Bosnian-born Yugoslav director Emir Kusturica, was released in the United States after it won for him the Best Director award from the Cannes International Film Festival the previous year.

The reference to Coppola's 1972 hugely successful Mafia family epic based on the Mario Puzo novel and screenplay is more than an American critic's effort to interest a home audience in a quality foreign film. For Kusturica's gypsy tale, based on actual newspaper stories, turns out to be not only a transfixing glimpse at a "parade of ethnic eccentricity" (Hinson), but a hymn to world cinema at a time when television has become the more dominant form of presenting moving images. Finally, this Balkan recasting of Coppola's Godfather and Godfather II (it was made before Godfather III appeared) also manages to go beyond such intertextuality and international border crossings to emerge as a "Yugoslav" text reflective of the cinema of that troubled country that tragically no longer exists in any discernible form. In this essay I use Kusturica's captivating film as a case study in a larger consideration of cinematic remakes viewed from the triple perspective mentioned above: how a film from a non-English-speaking, third world country may drastically remake a Hollywood film (films in this case), how

such a film can also allude to the cinemas of other nations and thus in some way announce itself as a member of the discourse of "world cinema" while maintaining its own cultural integrity as, in part, seen by its allusions to the cinema of its own nation. Not all elements of such a complex case of border crossing, as cultural-cinema critics such as Henry A. Giroux have explored the term, can be thoroughly illustrated in such a short piece as this. But it is my hope that this essay furthers cross-cultural cinematic studies.

Rather than remake The Godfather in any overt sense, however, Kusturica, a Bosnian filmmaker from Sarajevo, has made over Coppola's work to reflect Kusturica's own personal and cultural (Yugoslav) interests. In fact, Kusturica has often used The Godfather more to point to contrasts than parallels, culturally and cinematically.

Most attention paid to cinematic remakes involves Hollywood films, which we can consider either from the purely capitalistic urge of the industry to make more profit on a proven product or, as Leo Braudy has suggested in his remarks in this collection, the larger view of movie remakes as metaphorically reflecting "the history and culture of this self-made and self-remade country" (330). But I wish to look into that area of cinematic remakes, mentioned above, that has received little critical scrutiny: what I call the cross-cultural makeover. If Hollywood is indeed the acknowledged dominant cinema in the world, the ways in which minority cultures appropriate and make use of that dominant discourse can prove instructive for both narrative film studies and cultural studies. Taken all together, this investigation should reinforce Victor Shklovsky's keen observation that "[i]n the history of art, the legacy is transmitted not from father to son, but from uncle to nephew" (49).

Narrative in any form is, as Edward Branigan reminds us, "[o]ne of the most important ways we perceive our environment" (1). But, as he also notes, narrative depends on building story structures "based on stories already told." In Branigan's useful analysis, narrative is studied both for the process of generating stories and for the act of comprehension. In either case there is the need for a level of experience that recognizes patterns of storytelling and thus the sense of a backlog of "stories already told" that are shared by storytellers (authors, filmmakers) and audiences. In most cases, of course, recognized patterns do not suggest a direct adaptation of a set tale but rather a range of similarities. In such a manner, we could, for instance, identify one kind of story "already told" as belonging to a "coming of age" pattern. As Branigan notes, "'[M]eaning' is said to exist when pattern is achieved" (14).

We recognize the remake as a more intensified and self-conscious form of the narrative process described by Branigan. Within the territory of the remake, "meaning" involves the knowledge of specific texts, not only for their patterns but for their characterization, tone, texture, and point of

view. Even more so than other forms of narrative, the remake announces itself as negotiating a self-conscious balancing act between the familiar and the new or the familiar "transformed."

Finally, what I will term the "makeover" is a particular form of remake that purposely sets out to make significant changes in what is either acknowledged or perceived as a prototype or important precursor to the film in question. Seymour Chatman has distinguished between overt and covert narration depending on the "degrees of audibility" of narrators (196). This distinction can also be applied to remakes. Films that clearly announce themselves as remakes in one or multiple ways are "overt" recastings, while the makeover is constructed to be more covert (by varying degree) in its audibility for the viewing audience. Makeover as a term will help us to emphasize the characteristics and strategies, overt and covert, of difference that the film in question presents in terms of previous texts while also noting possible levels of connection, similarity, continuity beyond various borders, geographic, intellectual, imaginative, and cinematic. Jean Renoir was fond of saying that he was not able to become a filmmaker until he realized his love for von Stroheim, Chaplin, Griffith, and Keaton had to be transformed into his own French "language," cinematic and linguistic, since he was, after all, French (Durgnat, 9).

Making over Narrative:

Family Business

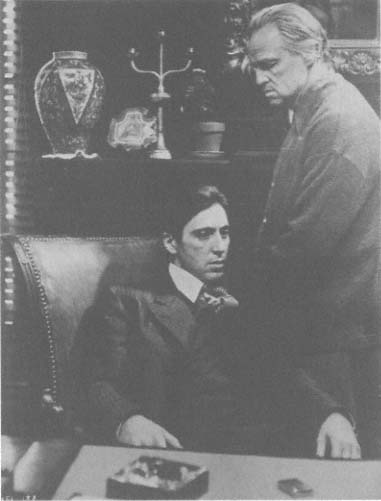

At the core of the fabula, or story, of both Godfather films is what Coppola's characters call the twin peaks of their lives: the personal ("family") and "business." Building on Puzo's novel, Coppola managed to infuse the Hollywood gangster genre with a richly textured double dose of the Italian American immigrant experience in the United States and the importance of family life to that experience. As Peter Cowie has observed about the first part of the trilogy, "[T]he film is really a paean, not so much to the Mafia as to the pioneer spirit that enabled generations of Italians to sail to the USA, settle, and establish a new caste of ironclad proportions" (53). (See figure 22.)

Note to what degree Coppola's two films exist not as prototypes for Time of the Gypsies but as complex examples of stories "based on stories already told." On the most immediate level, The Godfather is an adaptation of the novel with the added connection that the script was written by the novel's author. And Godfather II thus appeared as a sequel. A further exploration, however, would have to discuss Coppola and Puzo's "rewriting" of the cinematic genre of the crime film. It is just as important to our understanding of Coppola's films to know what kind of border crossing Coppola has done between the various films that make up the genre of previous mob-crime

Figure 22.

The godfather, Marlon Brando (with Al Pacino), takes the role of

the gangster patriarch far beyond the genre stereotypes

of the past in The Godfather (1972).

films as it is to study the process of adaptation from Puzo's written page to Coppola's moving images. Noting such a complexity in speaking about Hollywood cinema, Raymond Bellour has observed that "in the classic American cinema, meaning is constituted by a correspondence in the balances achieved. . . . Multiple in both nature and extension, these cannot be reduced to any truly unitary structure or semantic relationship" (99).

Acknowledging such a pluralistic state of balances and meanings within

Figure 23.

A Balkan family portrait: Perhan (Davar Dujmovic), far right, standing

next to his beloved grandmother (Ljubica Adzovic), is the young Gypsy

who later becomes a gypsy Mafia member in Emir Kusturica's Time of the

Gypsies (1989), a makeover of Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather .

Coppola's texts as, to one degree or another, makeovers of previous crime films as well as adaptations of a novel, we can now turn to Time of the Gypsies and the even more complex nature of the makeover.

Kusturica's saga follows a similar story-subject perspective—that of business and family. Time of the Gypsies is an epic chronicle of a young Serbian gypsy, Perhan (Davor Dujmovic), from awkward adolescence through puberty, young love, travel, involvement in a godfather-controlled crime network in Italy, and on to his eventual marriage, fatherhood, godfatherhood, downfall, and death.[1] (See figure 23.) Perhan's struggle, like that of The Godfather 's Michael Corleone, is between his strong sense and need of family and the pressures on him to go into the "business," in this case a crime empire dedicated to selling gypsy babies and exploiting cripples, dwarfs, and women (via prostitution) across the border in Italy (all based on true accounts of over thirty thousand gypsy children "sold" into such slavery by their parents and other relatives, a practice that has not ended). Beyond these plot and thematic similarities to the Coppola films, the differences mushroom in the fertile soil suggested by The Godfather and Godfather II .

For our purposes, I shall focus on both the cinematic (including narrative) and cultural differences that Kusturica's text evokes, with the addition of an extra observation: Part of the pleasure of Coppola's trilogy is that of watching the high level of professional acting, in many cases by actors such as Marlon Brando and Al Pacino, who began their film careers with impressive stage backgrounds. Kusturica, in contrast, has gone in absolutely the opposite direction, using predominately nonprofessional gypsies to play themselves, though the roles of Perhan and Ahmed especially are played by well-known actors.

If we embrace the totality of difference served us by Kusturica and his screenwriter Goran Mihic,[2] we could describe the fabula-plot of this Balkan makeover in the following way: Time of the Gypsies is a dramatic-comic tale told with both realism and dreamlike fantasy, full of cinematic references, concerning an Eastern Orthodox Serbian orphan gypsy with certain telekinetic powers who is raised within a matriarchal culture by his grandmother. He becomes a gypsy godfather but ultimately fails to mature due to the lack of a proper father figure. He finally tries to resolve his personal crises by murdering his adopted "godfather"-father and is in turn murdered by the godfather's latest bride. His dying expression, however, is not one of pain but is instead a satisfied smile as he sees a vision floating above him suggesting his dead mother, wife, and beloved pet turkey. Rather than a sense of loss, Perhan's death has brought him a deeper peace and seeming understanding. On a deeply spiritual level, he has been fulfilled.

Let us now explore more closely the nature and implications of Kusturica's makeover, beginning with the level of the cinematic border crossing.

Making over Coppola's Godfathers

Style:

Gothic Realism vs Magic Realism

Coppola's style in the trilogy might be termed "gothic realism"—a blending of realistically based scenes shot in deep expressionistic tones and shades, with no flights of fantasy or dreams within the narrative. In strong contrast, Kusturica's film is, as I shall discuss more fully, dream oriented. Perhan's trickster figure Uncle Merdzan tells him at one point, "I see life as a mirage," and so do we for two hours as Kusturica treats us to frequent dream sequences and fantasy-like realities heavily influenced, according to Kusturica, by Gabriel García Márquez and the South American tradition of "magic realism."

The impermanence of gypsy life is more than one of physical mobility: it is a condition of the spirit, a perception of the universe, which Kusturica captures in his overall style and approach to his narrative. The gypsies, he told a New York Times interviewer, "move . . . easily from reality to illusion to

dream, as in a Gabriel García Márquez novel. Time of the Gypsies belongs entirely to the world of García Márquez and other Latin American writers who built their art on the irrationality and poverty of their people" (Insdorf). Thus, while a study of Coppola's films should, as we have noted earlier, incorporate a stylistic and narrative study of the American crime film genre, Kusturica's film could also be fruitfully studied in relation to the tradition of literary magic realism, suggesting once more the plurality of meanings Bellour alludes to in "reading" films.

Cinematic Tone:

The Tragic vs the Joyfully Comic

Coppola's vision, especially when taking the trilogy as a whole, is one of tragedy, of loss, of a falling apart as he himself has commented (Goodwin, 161–93). Kusturica's gypsy epic is one of what he calls "joy," a term that embraces "happiness and sorrow." This double vision is particularly reflected in the Charlie Chaplin motif worked throughout the film, including the final image of Uncle Merdzan, who has consciously acted out Chaplin for the amusement of the family earlier. We see him leave Perhan's funeral and run off through mud, wind, rain, his back to the camera, coat clutched, a cane in hand à la Chaplin. One could argue that Chaplin's solo endings in his films actually push us finally into melodrama rather than the comic. But the memories we have of Chaplin and of Kusturica's work is one tinged more with the comic than the tragic, though we are aware in both cases that the comic embraces pathos as well as laughter (Horton, Comedy/Cinema/Theory , 5).

Kusturica's Salute to World Cinema in an Age of Television

Coppola's Godfather films build on the whole American tradition of crime genre films. But Kusturica cuts a much larger territory of cinematic border crossing with direct and indirect references to over forty directors, ranging from the surrealism of Luis Buñuel to the straightforward, clean, narrative visual style of John Ford. Part of Kusturica's cinematic makeover strategy in Time of the Gypsy results in an anthology of allusions and homage to Yugoslav and European cinema, as well as to classical Hollywood movies. When Perhan becomes a godfather and dons the appropriate looking clothes, he winds up appearing remarkably like Al Pacino. At one moment, he stands in front of a movie theater playing Citizen Kane . As Perhan goes to light his cigar, he sees a still of Orson Welles with an unlit cigar in his mouth. Before lighting his own cigar, Perhan holds the match up to Orson Welles's Havana in a double allusion and tribute to Welles and, we can add, to François Truffaut, who staged a similar Wellesian homage in his first

feature, 400 Blows (1959), as well as in his later hymn to filmmaking itself, Day for Night (1973). Thus, while the overriding nod in The Time of the Gypsies is to Coppola's two films, Kusturica is at pains for us to understand that he is involved in a much larger cinematic world of influences and allusions.

It is significant that two of the most important European films of 1989 concern a double interest in the odyssey of young males trying to come of age and in the presentation of their narratives within a cinematic context that pays homage to, and asks for authentication from, a tradition of world cinema. I am speaking, of course, of Time of the Gypsies and the Italian-French Oscar-winning production of Giuseppe Tornatore's Cinema Paradiso . Like Perhan, the young boy in Cinema Paradiso must grow up without a father. But unlike his gypsy counterpart, the Italian boy has a grandfather figure in the character of a small town movie projectionist played by Philippe Noiret.

Even more striking, however, is the way in which both films embrace through allusions, film clips, and cinematic quotations their respective national film traditions and that of classical Hollywood and world cinema. Of course, in casting a narrative around, and in, a movie theater, Cinema Paradiso allows for a more overt dialogue on cinematic homage and a simultaneous need for authentication. But before discussing particular cinematic influences contained in Kusturica's makeover, we need to understand that both of these European films announce themselves as nontelevision at a time when television has not only supplanted cinema as the major entertainment form but has done so in an age when cinema has, in order to survive, in many ways become television. Kusturica wishes to celebrate particular masters of the cinema and their works—Yugoslav, Hollywood, and European—but he is also necessarily making it clear that he wishes to be authenticated and included in their company, in the family of national (Yugoslav) and world cinema.

The dilemma of world cinema today is well captured by Todd Gitlin when he notes: "More and more, movies themselves have turned into coming attractions—fodder for TV (and radio) morning shows, local and national TV news, syndicated shows like Entertainment Tonight, national magazines from People to Vanity Fair, USA Today and the newspaper style sections, novelizations, comic books, theme song records, toys, T-shirts, and, of course, sequels. The sum of the publicity takes up more cultural space than the movie itself" (15–16). Cinema Paradiso might more aptly be retitled Cinema Nostalgia , and Time of the Gypsies as Time of the Filmmaker as Gypsy . For in every way, Kusturica's film announces itself as a film and not as television. The allusions starting with Coppola and The Godfather are many, but 99 percent are to cinema and not the tube. And they may be called hymns to the movie-going cinema experience as well, for it is more than a sense of narrative closure that requires in Cinema Paradiso the blowing up of the

local cinema (and thus the main character's youth) to build a parking lot: a way of life has gone and the age of video and television has triumphed. Similarly, the very beginnings of love and sexual awakening take place in Kusturica's film as Perhan and Azra watch an important Yugoslav film (Rajko Grlic's The Melody Haunts My Memory [Samo Jednom Se Ljubi , 1980]) in a makeshift open-air cinema and try to imitate the passion on the screen while Perhan's pet turkey looks on.

Thus in our post-postmodern media times, when even American presidential candidates communicate with their audiences via television by mentioning television in the form of shows such as Murphy Brown, The Simpsons , and The Waltons , Kusturica places his Balkan-Hollywood film (produced and released through Columbia Pictures during the closing days of David Puttnam's reign) squarely within a realm of reference that champions the cinematic experience for filmmakers and viewers alike.

Within this context, Kusturica's vision is one that includes both a realist and a surrealist tradition: thus does John Ford meet up with Luis Buñuel within this gypsy cinematic caravan. These extreme borders go beyond individual filmmakers, of course, for to mention Ford and Buñuel is also to embrace the classical Hollywood tradition and the anarchistic European avant-garde at the same time.

Kusturica has often spoken of his love of Ford's films.[3] And there are many scenes in Kusturica's films that share a general set up of straightforward dramatic confrontation with simple camera work reminiscent of Ford's approach. Furthermore, there are direct allusions to Ford's work, as in the closing scene of Kusturica's first feature, Do You Remember Dolly Bell? (Sjecas Li Se Dolly Bell? 1981). In the final shot, a Bosnian family is loaded into an open truck with all of its belongings, and they begin to drive toward a new home. The direct reference to The Grapes of Wrath is not just cinematic but thematic as well: the family has suffered but will survive, despite all odds.

There is much in Time of the Gypsies that echoes the playful surrealism of Buñuel. We can sense something of Buñuel's spirit in much of the absurdity that Perhan encounters, in the use of dreams and visions, in the unexpected plot twists and digressions (Buñuel, "Digression Seems to Be," 166), and in an atmosphere of magic realism in which forks fly and whole houses can be pulled from their foundations by a simple pickup truck. Kusturica, like a gypsy, has stolen from everyone, including from his native Bosnian and Yugoslav tradition for folk surrealism and magic realism (Horton, "Oedipus Unresolved," 68–74). Remember, for instance, the appearance of the Virgin Mary a few years ago in the little town of Medjugorje in Bosnia, an appearance that may well owe just as much to folk surrealism as to religion.

At heart, however, there is more of John Ford's style in Kusturica's work

than there is of even Coppola, Buñuel, or any other cinematic father figure. John Ford's darkly humored acceptance of people goes beyond the sense of tragedy, loss, and alienation pictured in Coppola's trilogy. These words of Ford's could easily be Kusturica's: "The situation, the tragic moment, forces men to reveal themselves, and to become aware of what they truly are. The device (a small group of people thrust by chance into a dramatic situation) allows me to discover humor in the midst of tragedy, for tragedy is never wholly tragic. Sometimes tragedy is ridiculous " (Gallagher, 81; italics my own).

Taken together, all of these intertextual, Hollywood, European, and other national cinematic "quotes" strongly suggest that Kusturica wishes his film to be taken as a member of a club that includes not only Hollywood but world cinema itself.

The Yugoslav Film Connection

Coppola managed to stamp a decidedly Italian American mark on one of Hollywood's most popular genres. Kusturica, however, announces himself as both an heir to Yugoslav filmmaking—ironically only a few years before such a label no longer had meaning for a country and an industry deconstructed by strife, war, and rebellion—and also to world cinema. Within this tradition, Kusturica's homages are numerous. For the title and subject matter of the film—gypsies—the filmmaker is indebted to Alexander Petrovic's I Have Even Met Happy Gypsies (1967), the film voted the best Yugoslav film ever by a hundred critics in the 1980s and winner of the Best Film award at Cannes in 1967. Kusturica owes much of his tone and atmosphere—emotional and locational—to Petrovic's pioneering tale of the rough life of Yugoslav gypsies in their ambiguous relationship, at the time, to a communist-socialist state.

Among the twenty or so other Yugoslav films alluded to in The Time of the Gypsies , one feels Kusturica has most clearly nodded to Zivojn Pavlovic's When I Was Dead and White (1967), which was co-written by Kusturica's screenwriter, Goran Mihic. In that film, for instance, the main character is shot to death in an outhouse with his pants down, much as the godfather's assistant is gunned down by Perhan in Gypsies .

There is also Goran Paskalovic's Guardian Angel (1987) which treated the same story as Kusturica's film but two years earlier: the true story (widely reported in the press and on television) of Yugoslav gypsy children being sold into slavery. Also incorporated, directly this time, is Rajko Grlic's The Melody Haunts My Memory , a clip of which is shown in the film (see below). And the use of magic realism to express the reality of those who have died echoes a similar use of the technique in other Yugoslav films, most clearly in Srdjan Karanovic's Petria's Wreath (1980).

All of these Yugoslav film allusions are lost, of course, on viewers not familiar with Yugoslav cinema, which is to say most world viewers. But that is not the point. What is significant is that within the context of world cinema, Kusturica's text suggests how a film can embrace multiple connotations aimed at a variety of audiences. David Bordwell speaks about the "degree of communicativeness" in a film narrative (59) and notes that such a degree can be judged "by considering how willingly the narration shares the information to which its degree of knowledge entitles it." By making over many of the elements of two Hollywood films—Coppola's texts—Kusturica's film provides an overall wide degree of communicativeness or access to his Yugoslav story. But in his allusions to Yugoslav cinema, he has purposely built in a "home culture" element that speaks to those who know, without detracting from the pleasure and involvement the film has set up for the non-Yugoslav audiences. We are aware that such narrative layering is common in many forms. For example, Groucho Marx's asides are missed by many and a great pleasure to those who "get" them, but the existence of the asides themselves does not detract from the overall impact of a Marx brothers' comedy. Similarly, but on the level of cross-cultural, cross-cinematic tradition, Kusturica's border crossings speak to multiple audiences simultaneously.

Making over One's Own Career:

Cross My Gypsy Heart

Kusturica has, finally, made over his own themes and narrative concerns in The Time of the Gypsies . When asked by his son at the train station if he will return, Perhan looks at him and promises, "Cross my gypsy heart." Of course, like everyone else in the film, he breaks his promise. The complexity of the oedipal situation is thus passed from Perhan to the next generation, setting us up for the conclusion in which the son steals the gold coins off his father's eyes during the funeral.

In his essay on Spielberg's Always in this collection, Harvey Greenberg has explored clearly the oedipal implications of the cinematic remake. For recasting a film that another "father" has produced is both the son's effort to replace the father and, in choosing to use the same text, a nostalgic wish to hold on to childhood and the past. Kusturica's nods to Coppola's films are both a challenge and a form of asking for a blessing by striving to be a member of the cinematic family and business, both within his culture (the former Yugoslavia) and beyond: Hollywood, Europe, and the world.

In addition to such a traditional oedipal situation, however, exists the effort of the filmmaker to remake himself. Thus, we conclude that beyond Coppola and world cinema, Kusturica has "made over" his own films as well.

Thematically all three of his features have been male coming-of-age stories. This is particularly true of the film previous to Time of the Gypsies, When Father Was Away on Business , which won the Best Film award at Cannes in 1985. In that film we see a similar use of magic realism and dreams of flight as the main protagonist manages to "fly" over Sarajevo in his dreams and, perhaps, in reality as well in this tragicomic view of the post-Stalinist 1950s in Yugoslavia, when the boy-protagonist's father is not away on business but in prison on trumped up political charges. Also present in When Father is the actor Davor Dujmovic, who stars as Perhan in Time of the Gypsies . Furthermore, in his first film, Do You Remember Dolly Bell? (1981), Kusturica presents a tale involving sexual initiation of a young male who is in conflict with a number of father figures who surround him, a motif also reflected in When Father and Time of the Gypsies .

Making over Culture:

Four Levels

Beyond the cinematic, the makeover calls attention to multiple cultural differences. As a Bosnian-Yugoslav making a film about gypsies in the gypsy language with Hollywood studio money, Kusturica was clearly involved in a "multicultural" project. Moreover, the echoes to Coppola's films serve to delineate more sharply, as reviews of the film have shown, the differences of cultures, turning all audiences into border crossers. Four cultural dimensions are studied here.

Making Over Theme:

The Stolid vs the Impermanent

While the thrust of the Puzo-Coppola trilogy is toward assimilation and the legitimization of their Italian American immigrants and their descendants, Kusturica's gypsies are shown to exist as they always have and, supposedly, always will: on the fringe, outside any traditional European cultures by choice . As Richard Corliss noted, these gypsies are "a Third World nation of wanderers, displaced and dispossessed in the midst of European bounty" (82). The opening ten minutes of The Godfather projects an overwhelming sense of solid, stolid immobility: the men in Don Corleone's study seem rooted to the heavy furniture and deep shadows. Kusturica's film reflects the impermanence of gypsy life itself. Within the cinematic frame, all is motion. And between cuts, characters constantly drift between Yugoslavia and Italy and back again. But there is more: the dominant motifs of Kusturica's film are of floating—people, animals, ghosts, objects including houses—and of the sound of the wind. It blows through the entire film, much as Gabriel García Márquez's wind blows through One Hundred Years of Solitude .

A key image is that of Perhan's house being literally pulled off its foun-

dations during a thunderstorm by his drunken Uncle Merdzan (it seems unlikely that the "merd" is an accident of naming). Merdzan has tied one end of a thick rope to the roof and the other to his mini-pickup truck and simply yanked away. That the security of home can so easily be destroyed becomes a lasting image for the film's audience.

The border crossing in this case is one of culture. Clearly Kusturica could have tried to make a film that did not consciously (even covertly) echo previous Hollywood texts, but in the realm of cultural discourse we realize that, by making over a familiar movie text, Kusturica is able to use his border crossing to highlight "different contexts, geographies, different languages, of otherness" (Giroux, 167).

Making over Patriarchs into Matriarchs

The Godfather trilogy is heavily patriarchal. By contrast, Time of the Gypsies , like gypsy culture itself, is strongly matriarchal. Even what could be called the theme song—a haunting gypsy Orthodox hymn to Saint George's Day—is sung by a young woman. The gender implications that radiate from such a makeover of Coppola's crime classics are profound, indeed. Kusturica's opening shot is of an unhappy bride and an unconscious (passed out drunk) groom. The gender pattern is immediately established: women survive and grieve while men pass out, leave, disappear, die.

Almost literally we feel in Kusturica's film that the center of Perhan's universe is his grandmother, Hatidza (played with poignant intensity by a gypsy, Ljubica Adzovic). She is a mountain of a woman who embraces her grandchildren with tears, laughter, advice, strength and who, of course, has a cigarette constantly dangling from her lips. Gypsy life is a kind of impermanent dream-myth, and it is Hatidza who is the mythmaker as well as the possessor of special powers. Perhan's odyssey toward becoming a godfather is set in motion when Hatidza is summoned by the current gypsy godfather, Ahmed (played with Brando-like expressions and gusto by Bora Todorovic, the all-time leading star of Yugoslav cinema)[4] , to save the life of one of his relative's sons. When she does so, Ahmed offers to take on Perhan as an apprentice in the "business" (Perhan does not yet know that it involves selling and exploiting Gypsy children).

Hatidza as healer, mediator between local quarrels, grandmother, substitute mother/father figure, and myth weaver embodies gypsy culture itself. In the "lift high the roof" scene already mentioned, Hatidza comforts a frightened Perhan and his sister by telling them this creation myth: "Once upon a time the Sky and Earth were man and wife. They had five children: Sun, Moon, Fire, Cloud, Water, and between them, they created a fine place for their children. The unruly Sun tried to part the Earth and the Sky, but

failed. The other children tried too but failed. But one day the Wind lunged at them and the Earth was parted from the Sky." Dream, reality, myth, and motherly concern all blend together at such a moment. Kusturica's film grows out of the reality of gypsy life and crime today, but it also embraces the mythic creation of the earth itself. Within the particular narrative of the film, the damage done by a man (the uncle) is handled by Grandma. The pattern continues throughout till we see Perhan's corpse laid out in the same home, with Hatidza mourning and yet carrying on as she must.

Fatherly Blessings Given and Absent

Building on the previous point, the parallel journeys of Michael Corleone and Perhan Feric as young males differ greatly. Michael's odyssey is one of growing into adulthood, as the Don "blesses" him while passing on the godfather role to him. Perhan, in contrast, is an orphan who never knows his father or mother. In fact, given Hatidza's mythmaking powers, there is no proof that the story she tells Perhan about his parents—that his mother was a very beautiful woman who died in childbirth and his father a handsome Slovenian soldier—is true. Either way, Perhan has no true father to pass on the "blessing" that commentators such as psychiatrist Peter Blos note is necessary for any boy to become a male adult (32). On a psychological level, therefore, Kusturica's protagonist and film are "frozen" in the world of a male adolescent who cannot come of age.

Coppola and Puzo's Michael Corleone has the task of accepting his father's blessing, making sense of his ethnic family and business heritage, and renegotiating these elements within a changing American culture. The male-centeredness of Coppola's trilogy is well captured in the opening sequence of The Godfather . While it is quickly established that the wedding of Don Corleone's daughter is taking place outside on a bright sunny day, the center of attention is the group of men gathered in the Don's darkly lit study. The strong sense of the father never leaves The Godfather trilogy and, we might add, culminates in Godfather III with the father figure of the pope as a significant image.

Perhan's world in Time in the Gypsies is quite the opposite. The film's opening shot of the unhappy fat bride has already been mentioned. From this shot on, Kusturica surrounds Perhan with women. He cares, for instance, for his sick sister (his initial reason for leaving home with the gypsy godfather is to help heal his sister).

But most important, his life intertwines with his true love, Azra (Simolicka Trpkova). It is with Azra that he first experiences love, sex, and companionship and, ultimately, marriage, the birth of a son (which may or may not have been fathered by his uncle), and death, as Azra dies in Italy. Perhan's

conflicted feelings for Azra—should he believe that her son is his?—are, of course, another expression of his failure to find an appropriate father figure to help him grow into maturity.

In an earlier scene, however, there are no conflicts at all. Kusturica orchestrates one of the most hauntingly beautiful scenes of sexual initiation ever to reach the silver screen. The moment happens immediately after Perhan's grandmother has described his parents to him. The scene is presented as a dream, as we see Perhan float through the sky clutching his beloved pet turkey on Saint George's day as a hymn to Saint George plays throughout on the sound track. As Perhan (and the camera) come down to earth, we see a river scene. Hundreds of gypsies with torches are gathered by the river to celebrate Saint George's day. On the river is a small wooden boat floating with Perhan and Azra, bare-chested, lying next to each other, playfully involved with each other.

Desire, religion, ritual, nature, music, and magic realism (dreams) all flow together in one "mirage" of sexual awakening. It is a joyous scene, the happiest moment of the film. Everything else in Perhan's life becomes a falling away from this moment of union with the woman he loves.

Nothing similar exists in the Godfather films. Men in Coppola's male-centered world exhibit no such pure joy in the presence of women, ritual, religion. Diane Keaton's "outsider's" role as Kay Adams is that of a proper Mafia wife and mother, with no sexuality presented or explored. Something much closer to the world of Time of the Gypsies is hinted at, of course, in the Sicilian romance and marriage scene as the young Michael courts a Sicilian beauty who is finally killed by a car bomb meant for Michael. But we never feel the completely embracing sense of women of all types that we feel in Kusturica's gypsy world.

Finally, for Perhan's female-centered universe we should mention the influence of his long-dead mother. She is represented by a wedding veil that trails through the sky at several points in the film. As Perhan dies, shot in the back by the godfather's new bride ("You ruined my wedding, you bastard!"), he looks heavenward and sees a combined image of the veil and his dead turkey, an image that unites his mother, Azra, and his pet.

Thus, much of the poignancy of Kusturica's film is that of a young male unable to become a man who both appreciates (loves) and fears the power and mystery of women.

Catholicism vs the Orthodox Faith

Coppola's trilogy draws a deeply ambivalent portrait of the Catholic Church and uses Catholic ritual as an important structuring device within the films. Kusturica's film, similarly uses church ritual and custom throughout, but it is the Orthodox faith of the Balkans (more specifically, the Serbian Ortho-

dox tradition). The prime example is the one just given: Perhan's sexual initiation takes place within the comforting frame of a traditional religious holiday, Saint George's Day. Religion for the gypsies is tied together with family, tradition, custom, culture, and personal identity.

It is not so in The Godfather . Clearly, one can map out The Godfather according to the Catholic rituals of a wedding, funerals, and, finally, a baptism. But Coppola introduces Catholicism in order to undercut it ironically (Hess, 84). For it is during a baptism that the baptism of blood takes place in parallel editing, as Michael has ordered a shooting of all rivals at the very moment he is at his sister's child's baptism. For Coppola's gangsters, Catholicism is omnipresent. But it is simply part of being "Italian American," rather than a spiritual force capable of guiding individuals in their lives. John Hess speaks well of Coppola's critical view of the church: "Religion is still an important prop of bourgeois ideology, and the church also represents a community of sorts. But by juxtaposing it with its opposite—murder, hatred, brutality—Coppola implicates the Church in this activity. By showing the Church's inability to comfort anyone, Coppola shows its impotence. It is one more bourgeois ideal that does not work" (87).

Godfather III caps all of Coppola's ambivalent feelings about the church, of course, as even the Vatican is drawn into mob activity.

Religion, finally, for Kusturica and his gypsy culture, is tied strongly to folk mysticism as the dreamlike magic realism scenes of floating veils and the floating pet turkey viewed in death, as well as the whole motif of Perhan's telekinetic powers, suggest. For the gypsies, Time of the Gypsies suggests, are part pagan, part Christian, part believers, part passionate hedonists. As in their lives, so in their faith: they live within a sense of multiple possibilities.

Stolen Coins:

Crossing All Borders

Leo Braudy puts it well in his remarks in this collection when he speaks of remakes as a form of "unfinished cultural business." The ending of Kusturica's gypsy narrative, with the young boy who may or may not be Perhan's son stealing the coins off Perhan's permanently sealed eyes before his burial, leaves us with a key to survival for gypsies: steal and run.

It is the perfect closing scene for a film about a culture that has survived because it exists beyond the cultural, political, spiritual, and economic borders of more stolid cultures by being itself perpetually "unfinished," impermanent, and in motion.

Finally, then, Kusturica's film is a survivor too because it refuses, like the gypsies, to be assimilated and identified completely with any one cinematic tradition. The perpetual state of making over cinematic texts and allusions,

with Coppola's The Godfather and Godfather II being the primary object of plundering, locates Kusturica in the "unfinished" state of being a Bosnianborn filmmaker who has gone beyond the borders of geography, politics, language, and regional culture (though he does strongly represent these as well) to "steal" from the international currency of cinema.

This "gypsy-" like approach to narrative and cinema is not the only one available to filmmakers from minority non-English-speaking cultures, of course. Theo Angelopoulos of Greece and Andrei Tarkovsky of Russia, for instance, created internationally praised films by turning away from classical Hollywood and European narrative traditions, cinematic and otherwise.

But Time of the Gypsies is a vibrant example of how the more recognized border crossing represented by Hollywood remaking the films of other cultures can be reversed with imaginative cinematic and provocative cultural implications.

Our parting shot takes us outside of cinema itself.

It is tragically ironic that Kusturica's first film Do You Remember Dolly Bell? ends with a tracking close-up of the main character, our young male rock 'n' roll singer, who, in voice-over as he rides in the back of a truck headed for a new apartment building, says, "In every way, every day, things are getting better." That same skyline in 1995, as this essay is completed, has been blown apart, and millions of the people have been left homeless, almost three hundred thousand murdered, and many others raped and tortured. The all-embracing range of Kusturica's cinematic vision has, in reality, become a nightmare of ethnic hatred that the darkest Hollywood war or crime genre film could not envision.

We can only hope that cinema itself can prove to be one form of border crossing beyond the boundaries of hatred, violence, and death.

Works Cited

Bellour, Raymond. "The Obvious and the Code." In Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology , edited by Philip Rosen. New York: Columbia University Press, 1986.

Blos, Peter. Son and Father: Before and beyond the Oedipus Complex. New York: Macmillan, 1985.

Bordwell, David. Narration in the Fiction Film. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985.

Branigan, Edward. Narrative Comprehension and Film. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Breskin, David. "Francis Ford Coppola: The Rolling Stone Interview." Rolling Stone , 7 February 1991, 60-66.

Buñuel, Luis. "Digression Seems to Be My Natural Way of Telling a Story." In My Last Sigh: The Autobiography of Luis Buñuel , translated by Abigail Israel. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1983.

Chatman, Seymour. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978.

Corliss, Richard. "A People Cursed with Magic," Time , 19 February 1990, 82.

Cowie, Peter, ed. "Francis Ford Coppola." Film Guide International (1976): 50–59.

Durgnat, Raymond. Jean Renoir. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974.

Gallagher, Tag. John Ford: The Man and His Films. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1986.

Giroux, Henry A. Disturbing Pleasures: Learning Popular Culture. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Gitlin, Todd. "Down the Tubes." In Seeing through Movies , edited by Mark Crispin Miller, 15–48. New York: Pantheon, 1990.

Goodwin, Michael, and Naomi Wise. On the Edge: The Life & Times of Francis Ford Coppola. New York: William Morrow, 1989.

Hess, John. "Godfather II: A Deal Coppola Couldn't Refuse." In Movies and Methods: An Anthology , edited by Bill Nichols, 81–90. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1976.

Hinson, Hal. "Drifting in the World of Gypsies." Washington Post , February 21, 1990, p. D4.

Horton, Andrew, ed. Comedy/Cinema/Theory. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1991.

———. "Do You Remember Dolly Bell? " In Magill's Survey of Cinema: Foreign Language Films , 486–50. Los Angeles: Salem Press, 1985.

———. "Oedipus Unresolved: Covert and Overt Narrative Discourse in Emir

Kusturica's When Father Was Away on Business ." Cinema Journal 27, no. 4 (summer 1988): 64–81.

———. "Yugoslavia: A Multi-Faceted Cinema." In World Cinema since 1945 , edited by William Luhr, 639–660. New York: Ungar, 1987.

Insdorf, Annette. "Gypsy Life Beguiles a Film Maker," New York Times , 4 February 1990, pp. 18, 25.

Mast, Gerald. A Short History of the Movies. 4th ed. New York: Macmillan, 1986.

Pachasa, Arlene. "Time for Kusturica." American Film (January 1990: 40–44.

Shklovsky, Victor. Quoted in Wallace Martin, Recent Theories of Narrative . Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1986.