Two—

Algebraic Figures:

Recalculating the Hitchcock Formula

Robert P. Kolker

Alfred Hitchcock was a director of elegant solutions. His best films are well-tuned cinematic mechanisms that drive the elements of character, story, and audience response with a calculated construction that creates, anticipates, yet never quite resolves the viewer's desire to see and own the narrative. Hitchcock's films make us believe that we understand everything even while they leave us unsettled about what we have seen and unsure about our complicity in the event of seeing itself. Even his less-than-perfect films, in which too much is spoken and too much resolved, there are sequences or shots of formal inquisitiveness that concentrate the attention and reveal a filmmaker who, although his interest is less than thoroughly engaged, can formulate a cinematic idea and calculate it to a small perfection. Hitchcock is one of the few commercially successful filmmakers who give the viewer pleasure by means of his formal deliberations. For popular cinema—a form of expression dedicated to hiding its formal structures—this is a major achievement.

But there is an unsettling anomaly at work here. The elegance of Hitchcock's formal structures and the pleasure we take in watching them in operation belie the content they generate: images and narratives of violence and disruption; attacks on complacency and routine; sexual cruelty and a disturbing misogyny are created in visual and narrative fields whose eloquence and intelligence seem to transcend their content. Something of a sadomasochistic pattern is put into operation. We reverberate to the shocks endured by Hitchcock's characters and take a peculiar pleasure in the way they are perceived and the way in which we perceive them. We delight in the cunning with which the director represents this violence and respond favorably to the eloquence of the moral ambiguities that result in our pleasurable assent to violence and madness. When we see culpability and evil

portrayed as the twins of innocence and rectitude, we accept this contradiction with an almost smug knowingness. The pain of the revelation of moral complexity and uncertainty (which repels us in, for example, the political sphere) is accepted in the aesthetic as the insight of a clever interpreter of modernity. The calculation of it all, the almost obsessive construction of narrative, the composition and cutting of shots that force us to respond in predetermined ways to seemingly uncontrolled or uncontrollable acts, Hitchcock's complete command of our perceptions, turns upon reception into delight. We find pleasure in his authority and enlightenment in his calculations. Hitchcock and his audience are able to have it all ways: plot, character, suspense, fear, pleasure; a formal structure never invisible, yet intrusive only when one desires it to be; a structure of moral ambiguity lurking below the level of immediate cognition, all firmly buttressing the pleasure of narration.

Hitchcock calculated himself as part of the overall structure of his work. He foregrounded his presence by appearing in his films; he developed an instantly recognizable persona on television; and he entered the popular imagination with a distinctiveness unrivaled by any other filmmaker in fifties and early sixties American culture. This success on all levels created the event of the director as celebrity. His films were known; and he (or rather the public persona he created) was known through the work of film reviewers, who referred to almost any film that used suspense, shock, or a "surprise ending," as "Hitchcockian." His work was conflated into an adjective and misappropriated as a genre. It's not surprising that, with all this, Hitchcock became a very special example to the generation of film students turned filmmakers in the late sixties and early seventies.[1]

This is a special group of writers and directors, which now dominates American filmmaking. While not all were students in the literal sense (a few of them, like Martin Scorsese, did take degrees in film school, while others may have attended briefly or not at all), they were a generation who learned about film by watching movies on television and in repertory movie houses. Unlike their Hollywood predecessors, who learned filmmaking as a trade, coming up the studio ranks, many of the young filmmakers of the late sixties and early seventies saw film as a form of expression: subjective and malleable. One manifestation of that expression, one way of impressing subjective response and a love of the cinematic medium was by alluding to and quoting from other films. Hitchcock and John Ford were the touchstones for these new directors, and the films—The Searchers (1956) and Psycho (1960) in particular—the foundation for much of their work.[2]

The phenomenon of allusion, quotation, and imitation in film is complex. We need to divide some of the strands of these activities to understand what the new filmmakers were about and how Hitchcock plays a role in their work. The business of filmmaking has always thrived on the fact

that viewers remember films, stories, stars, and genres. The repetitions and sequels and cycles that Hollywood needs in order to reproduce narratives in large numbers depended—and depends still—on the viewer's ability to recall, respond to, and favor particular films. There is a discrete contradiction operating here. The classic American style of moviemaking and reception depends upon transparency and a kind of virgin birth. Every film emerges whole and new, actively suppressing its technical, stylistic, or historical origins. Yet audiences are depended upon to recognize similarities and repetitions from film to film, and indeed they must do this. If they did not, they would have no desire to see stars, plots, generic elements, narrative patterns repeated; and without that desire to fulfill, Hollywood filmmaking could not exist.

The post-fifties, post-French New Wave generation of American filmmakers exploited the contradictions. They too looked to repetition and depended upon audience recognition, yet did not care to make their work completely transparent. They did not want to hide the genesis of their films or suppress the fact that films come not from life or from an abstract convention of "reality" but from other films. Their films recalled not only broad generic paradigms or the sexual attractions of certain players but specific images, the narrative structure of individual films, the visual and storytelling stratagems of particular filmmakers. They interrogated that aspect of filmmaking that combines commercial necessity (repetition and imitation) with the work of the imagination (allusion and quotation) in order to provoke the audience into recognizing film history, and in doing so pleased the viewer by asking for her response and her knowledge. The cinema of allusion is made out of a desire to link filmmaker and viewer with cinema's past and inscribe the markings of an individual style by recalling the style of an admired predecessor. At its worst, it is an act of showing off; at its best, a subtle means of giving depth to a film, broadening its base, adding resonance to its narrative and a sense of play, and, through all of this, increasing narrative pleasure.

Various filmmakers refer to and incorporate other films in various ways, as John Biguenet demonstrates in his essay elsewhere in this book. Among the most interesting are the subtle allusive acts that operate on the level of pure form. In these instances, allusion is not quite the appropriate term, for here filmmakers are working with and advancing basic visual experiments tried out by their predecessors. Hitchcock is a particularly apt example, because he was constantly playing with formal devices, looking for ways in which elements of composition, cutting, and camera movement could be employed to express a state of mind or clarify perception, to bring the viewer into the progression of the narrative or hold her at arms length.

When Spielberg uses a formal Hitchcockian device in Jaws (1975), combining a tracking shot with a zoom, each moving in opposite directions, to

communicate a tense moment of perception and recognition, the result is powerful and terrifying. Hitchcock had experimented with the technique in Vertigo (1958) to indicate Scottie's fear and loss of control as he hangs from a roof or races up the steps of the mission steeple. He used it as a point-of-view shot, expressing his character's terrified perception of his situation. Spielberg expands its use to express not only the character's but the audience's response: it becomes the viewer's point of view as the sheriff, Brody, thinks he sees the shark in the water, while character and background simultaneously shrink from and expand into each other. Toward the end of Goodfellas (1991: a film of great, imaginative "tryings out" and experiments), Martin Scorsese refines the device even further. In a diner, Jimmy and Henry sit by a window, talking. The camera tracks very slowly toward them, while the scene outside the window zooms in at a faster speed in the opposite direction. The sequence impresses the characters' dislocation and prepares for the major turn in the narrative, when Henry betrays his gangster friends.

Such examples carry allusion beyond the point of play, inside joke, or plot device into the very system of visual narrative structure. They demonstrate that filmmakers work like artists in any other media: they learn from, copy from, and expand upon the work of their predecessors, exploring and exploiting their own tradition. The degree of success that each attains, however, is not equal. Brian De Palma, for example, has done the simplest arithmetic exercises based upon the Hitchcock equations. He alludes to Hitchcock's plot structures and plays with visual and editorial devices. Unquestionably, the majority of American filmmakers who attempt to recalculate the Hitchcock formula wind up diminishing the work of their subject. Rather than recreate or rethink the moral structures of the Hitchcock mise-en-scène, they simply exploit it, sometimes very quietly, as if out of desperation. Paul Verhoeven's and Joe Eszterhas's Basic Instinct (1992) is an example of an exploitation film in which sexual violence is made a metaphor for moral bankruptcy. But the metaphor is rendered useless because the film depends on its ability to sexually arouse its audience to assure its commercial success. The film enacts what it seems to condemn, leaving no space for introspection or comprehension of the viewer's own complicity in the film's narrative affairs. Despite the fact that Eszterhas keeps reaching into two of Hitchcock's most disturbing and questioning films about sexuality, Vertigo and Marnie (1964), he allows no space for speculation, only manipulation. A central premise of Vertigo , that male sexual obsession can be carried to the point of destroying both the subject and object of the obsession, is reduced in Basic Instinct to various sets of exclusive sexual provocations, in which a man and two women maneuver one another into sexual thralldom (a mainstay of popular romantic literature and middle-brow, commercial soft-core pornographic film), with the threat of death hanging

over every encounter. From Marnie comes the figure of the sexually tormented woman, psychologically broken into multiple characters, yielding, destructive, finally psychotic, and, in a ploy Hitchcock would never indulge, murderous.

Hitchcock's misogyny is well documented. But despite the suspicion and distrust of women manifested in much of his work, there is almost always an understanding that women, when they are figures pursued and possessed by men, are fantasies made up by men. They are (as Tania Modleski points out in The Women Who Knew Too Much ) fictions that belie innate personality and female desire, fictions that subordinate the female to the neurotic, often psychotic, male gaze. Notorious (1946) and Vertigo play upon this transformation, the latter film elevating it to a semblance of tragedy. Marnie examines the phenomenon in almost clinical fashion, as a woman, honest about her neurotic dysfunction, is reduced and finally raped by a man who believes he can transform her.

Eszterhas and Verhoeven do not care for abstractions or meditations on transformation. The central figures of Basic Instinct are present only to exploit and use one another, and the audience most of all. Hitchcock's troubled and abused woman is here turned into a sexual destroyer, and none of the shots of the Michael Douglas character driving along the California coast carry the weight of existential fear and sexual anxiety borne by Jimmy Stewart's Scottie as he pursues his phantom of desire through the streets of San Francisco. Basic Instinct is an example of the exhaustion of allusion and the employment of Hitchcockian technique as an act of exploitation and despair. To do Hitchcock may convince a filmmaker or his producer that he may be like Hitchcock, and with such similarity may come respect and admiration and ticket sales. But in the end, very few directors—perhaps only Martin Scorsese in America and Claude Chabrol in France—understand that recalculating Hitchcock means understanding the mathematics of the original formula, thinking the way Hitchcock thought, and reformulating the original so that the results not only allude to but reinterpret it. Again, it is a matter of comprehending Hitchcock's mise-en-scène: the spatial articulation of his films, which includes the way his characters are situated and the way they look at each other and are looked at by the camera. It is the mise-en-scène itself that gives voice to ambiguities of sexuality and the violence of the everyday, the subjects that most engaged Hitchcock in his best work.

Scorsese has made two films that actively engage Hitchcock. Taxi Driver (1976) reformulates Psycho (while it simultaneously situates its narrative pattern in The Searchers ). Within the figures, gestures, and ideological and cultural practice of the late seventies, Scorsese finds analogues for the return of the repressed, which Hitchcock represented in the late fifties. Taxi Driver incorporates dread, angst, and threat in the figure of Travis Bickle,

whose world is as tentative and malperceived as was Norman Bates's in Psycho. Cape Fear (1991), certainly a less complex and resonant film than Taxi Driver, uses Hitchcock in more devious ways than its predecessor. Rather than elide and reconstruct the methods of one film within another (as Taxi Driver does with Psycho, embracing as much as remaking it), Cape Fear uses Hitchcockian technique to solve some problems. Just as Hitchcock used the perceptual structures of film to solve thematic puzzles and simultaneously engage and distance his audience, Scorsese turns to Hitchcock to solve other kinds of problems and provide a kind of secret narrative structure for a film that even its director admits is a minor, unashamedly commercial work. Within this "secret narrative" lie some of the most interesting reformulations of Hitchcock, unobtrusively, and with a great deal of humor and play.

When Cape Fear was being edited late in the spring of 1991, Scorsese gave a talk about the filmmaker Michael Powell at the Library of Congress as part of a program celebrating British cinema. He made a number of interesting revelations. One concerned the extent to which his own imagination was nurtured by cinema, and the fact that the choices he made and the problems he solved in creating his films depended in excruciating detail upon other films. He said, for example, that the close-up of De Niro's eyes during Taxi Driver 's credit sequence was suggested to him by a similar shot of the eyes of a gondola oarsman in Michael Powell's little-known film, Tales of Hoffman (1951). This is more than allusion or the simple celebration of cinematic community. It is, rather, the activity of a profound, subjective intertextual imagination that links Scorsese with the modernist writers of the teens and twenties and with the cinemodernists like Godard in the sixties, who looked to the writers and filmmakers who proceeded them as the usable past that must inform their own work. For the modernist, a "new" text is built from the appropriation and accretion of other texts. In a basic, material way, modernism demands that the works of imagination remain viable and usable, that they exist as the seeds of other works. Through such incremental nurturing a history of the imagination is written.

At its very best, the modernist act of allusion reveals form and structure through dialectical play. A new work, coherent in its own structure, gains that coherence by absorbing and restructuring other works. A kind of imaginative space is marked out that is open to other spaces and in that openness is made secure. "These fragments I have shored against my ruins," T. S. Eliot writes—or rather quotes—in The Waste Land . This is intertextuality as imaginative redemption; and that is precisely what is going on in Cape Fear, a secret remake, knowledge of which reveals the film as joke and intricate reformulation, a way of knowing Hitchcock and absolving Scorsese.

At his Library of Congress talk, Scorsese made an admission of sorts. In return for the financial and moral support given The Last Temptation of Christ

(1988), he owed Universal Pictures six films. Cape Fear was the first of these, and it was consciously and eagerly made quickly, cheaply, and with an eye on the box office. As an indulgence in the thriller-horror genre, and drawing upon a multitude of sources, it was aimed to please its audience and its creator. Part of that pleasure was in the remaking of an earlier film of the same title and basic plot structure, J. Lee Thompson's 1962 Cape Fear (a Universal property). Were it only a remake of this earlier film, it would be a somewhat interesting aside in Scorsese's career, a successful attempt at a commercial film (as big a moneymaker as Scorsese has had and an even better film than an earlier commercial attempt, The Color of Money, 1986, which was itself not a remake, but an extension of yet another film, The Hustler, 1961). But it is apparent that Scorsese calculated to produce something more than a quickie remake. He would, in effect, create a number of remakes in one: within the remake of the 1962 Cape Fear would be embedded a kind of remake of three minor Hitchcock films from the early fifties: Stage Fright (1950), I Confess (1953), and Strangers on a Train (1951). In other words, having decided to do a minor film within his own canon, he turned to films in Hitchcock's canon in order to discover how a minor film could best be done: to try, in effect, to recreate a minor Hitchcock film. The result is still not anything more than a minor film; yet it is one that plays a game of intertextual counterpoint, a modernist exercise in popular form in which one film adopts the plot of its predecessor while gaining a deeper structure through an allusive tag game with three Hitchcock films. The result is enormous pleasure for the maker of the film and the viewer who perceives the games being played.

All this becomes even more interesting when we realize that Thompson's 1962 Cape Fear is itself a Hitchcockian exercise, a film that plays upon Psycho, or, more accurately, the atmosphere of Psycho and its reception. The production of Thompson's film is explicitly connected to Hitchcock. Bernard Herrmann, who wrote the score for Psycho (as he did for most of Hitchcock's fifties films), wrote the music for Thompson's Cape Fear . (Scorsese had Elmer Bernstein—an old hand at film music—reorchestrate a souped-up version of the same score for his film. He furthered the Psycho connection by having Saul Bass design credits somewhat similar to those he designed for Psycho .) George Tomasini, Hitchcock's regular editor, who cut Psycho, edited Thompson's film. Martin Balsam, who plays the detective Arbogast in Psycho, plays a police detective in Cape Fear . Gregory Peck, who had starred in Hitchcock's Spellbound (1945) and The Paradine Case (1948), plays Sam Bowden (Scorsese gives both Balsam and Peck small roles in his version of Cape Fear, as he does Robert Mitchum, the original Max Cady. (See figure 3.) There are visual references to Psycho in the 1962 Cape Fear, well before the time that allusions were to become prominent in American cinema: in the sequence where two detectives mount the steps in a boarding house

Figure 3.

Evoking Hitchcock through casting: Martin Balsam, Robert Mitchum,

and Gregory Peck in the original Cape Fear (1962) directed y J. Lee Thompson.

where Max Cady has brutalized a young woman, the camera tracks them up the stairs as it does Arbogast when he visits Norman's mother.

Thompson's film explores issues of violent sexuality, just becoming explicit in film as a result of Psycho . He examines "normal" middle-class people intruded upon by a psychotic, uncontrollable, and ultimately unknowable individual, and he observes an ordinary and plain middle-class landscape turned suddenly threatening by an amoral and dangerous presence. In short, Thompson attempts to recreate the mise-en-scène of Psycho: a gray, ugly world charged with violence and sadomasochistic sexuality, a world of ordinary people put in danger, a world of psychotic presences teasing and seducing middle-class morality and straining its oppressive limits. Psycho had come as a challenging and changing force onto the site of fifties American cinema, which, superficially, was as quiescent and predictable as the culture in which it was made. Few films outside of low-budget crime movies spoke to the political and moral despair of the period. To be sure, some of the decade's melodramas—notably those of Douglas Sirk and Nicholas Ray—suggested the fears and threats of domesticity on a social level above

that represented in the gangster film. But these works almost always indulged in an obligatory, if ironic, recuperation of at least one of the main characters in an attempt to negate the terrors of dissolution within the narrative. Hitchcock, in The Wrong Man (1956) and Vertigo, began a concerted effort to represent a world that was not recuperable, a world hostile to ordinary emotional life in which individuals were shown as helpless in face of uncontrollable events, incapable of normal responses, and destructive of themselves and others. Together, these films spoke the unspeakable in a decade devoted to amnesia and evasion. In Psycho , finally, the articulation of despair was stated with such violence that there was no longer a possibility of recuperation.

Psycho placed the grimness of The Wrong Man within the emotional abyss of Vertigo and out of the two created a physical and emotional landscape unrelievedly barren and violent. It did this with such force and self-consciousness, and such self-awareness, that it startled viewers not only with the blackness of its vision, but its humor, the unrelenting notion that some kind of joke was being played. Psycho, as its creator never tired of saying, was in fact a joke, a story that kept giving itself away in the process of its telling. But its playfulness made its seriousness all the more disturbing, and the force of its darkness penetrated American film and slowly changed it. Thompson's Cape Fear, coming less than two years after Psycho, was among the first to reproduce its fearsome insistence that the disruption of madness is a given in a world that counts on an illusory continuum of the ordinary.

But let's be clear. The 1962 Cape Fear has none of the complex resonance of Psycho . It does, in the character Max Cady, have its own version of Norman Bates, the madman who, from moment to moment, appears normal and self-contained (it is interesting to note that Scorsese, in his version of Cape Fear, is uninterested in this bit of Hitchcockian drollery: his Max Cady is a fearsome crazy man, a parody of recent unkillable movie monsters, a self-proclaimed "big bad wolf," a sadistic creep from beginning to end). It also has its middle-class family, a much more respectable family than Hitchcock's unpleasant petite bourgeoisie in Psycho, whose grim world is turned over by the madman's appearance. The origins of Thompson's family are the ordinary fifties domestic melodramas, not the grim hotel rooms and storefront offices of the inhabitants of Psycho . What the original Cape Fear takes from Psycho and exaggerates are its elements of sexual perversity and the inescapable attractions to evil, its bland black, white, and gray landscape that absorbs and gives back threat from the madman's indwelling. Here—though not as subtly as in Psycho —smugness and seduction, propriety and corruption work smoothly, implicitly together.

By 1991, few representations of sexuality and violence were still considered transgressive in cinema. The host of Psycho imitations during the intervening years had raised the ante of violence simulated and depicted to

appalling levels. In 1962, Thompson's Cady does the literally unspeakable and unseeable to the young woman he picks in a bar. The act goes on behind closed doors. Afterward, the woman will not even tell the police what Cady did, and she leaves town. In Scorsese's film, the young woman is sexually active and insecure, she was Bowden's lover, and Cady picks her up and brutalizes her not as a general threat to Bowden, but as a specific act of revenge. The act does not go on behind closed doors. We are privy to Cady's sadism: he breaks the woman's arm, bites a chunk out of her face, and spits it across the room. Scorsese, as is often his wont, throws representations of violence in our face because he likes to; because he knows a large part of the audience likes it; because (in his better films, at least) such images are among the articulate essentials of the world he is mediating and a vital component of the character is he is creating within this world. But something else is happening in his Cape Fear . Scorsese is attempting to refashion the moral landscape of the original film. His Sam Bowden is something of a pompous fraud who concealed evidence at Max Cady's trial (a morally correct but legally culpable act). Therefore, Cady's vicious actions come not from madness simply but from an insane sense of righteousness and revenge. Unlike his predecessor, he acts as Bowden's bad conscience; he is—and here Scorsese begins to get closer to Hitchcock—Bowden's double, his own corruption made flesh, the bleakest image of his own desires and destructiveness. Seduction and pain are not merely the ways Cady uses to get back at Bowden; they are ways of exposing the worst of Bowden to himself.

For Hitchcock, the creation of the double was a means of structuring moral ambiguity, which I noted earlier is so basic to his work. More than most filmmakers, he builds his mise-en-scène out of a counterpoint of gazes, of characters looking at each other and the viewer looking at the characters within spaces that contextualize those gazes as intrusive, threatening, and violent. The possibility of visualizing one character as a reflection of the other, or one act or gesture as a mirroring of the desire of the other, grows easily out of such structures. With looks and gestures, Hitchcock rhymes his doubles: Charlie and young Charlie are introduced with similar shots in Shadow of a Doubt (1943). Sam stands by his reflected image in the mirror as he attempts to face down Norman Bates in the motel office in Psycho . Judy-Madeleine in Vertigo is a double doubled: she is the fault line of Scottie's psychosis, his desire made impossible flesh. And in turn she is two women to him: one the person someone else created, who Scottie turned into the image of his beloved, the other the "real" woman he thinks is someone else and proceeds to recreate again into the image of his love. Often the doubling structure takes place in the exchange between image and viewer, the latter given an image of sadomasochistic desire through his or her assent to the characters' actions on screen and thereby becoming a kind of fantastic double of the character on the screen.

Each of the three fifties Hitchcock films that Scorsese draws on for his Cape Fear—Stage Fright, I Confess, and Strangers on a Train —is built on the concept of the double. Stage Fright is the most subdued of them. Were it not for the fact that it is so flat and arrhythmic, its performances so without energy, it could well be the most interesting, for it doubles and quadruples its doubles, setting up what should be an intricate structure in which many of the major characters play roles, making believe they are other than what they appear to be, and lie to themselves and the audience (the body of the narrative is told in a flashback that communicates false information), each reflecting the other's bad faith. Jane Wyman's Eve attempts to protect her boyfriend from the accusation of murder, one presumably committed by Marlene Dietrich's Charlotte Inwood (an aloof and potentially powerful character, who the film manages to humiliate and almost destroy in its rush to recuperate Eve). (Cf. Modleski, 115–17.) That the murder was committed by Jonathan, Eve's boyfriend, becomes fairly clear late in the film but is not fully revealed until a powerful sequence in which a clearly psychotic Jonathan admits his crime and his madness in the prop area of a theater. Scorsese draws this sequence, like a thread through the eye of a needle, into the high school episode of Cape Fear . In the 1962 version, Sam Bowden's daughter is pursued—or rather thinks she is pursued—by Cady in her school. Scorsese is uninterested in such simple images of pursuit and more concerned with the inexplicable sexual seductiveness of Cady and the effect of that seductiveness on Bowden's daughter. Echoing the penultimate sequence in Stage Fright, he places the man and woman in a stage set (here an expressionist image of a cottage on the stage of a high school auditorium) where Cady awakens the sexuality of Danielle Bowden and puts her under his control.

In the source sequence from Stage Fright, Eve retains a great deal of control in the face of the madman: both sit in the darkness with a slit of light over their eyes. One-shots—shots in which only one character is seen—of each predominate and the suggestion of mirroring images is strong. But Hitchcock is not quite able to press the doubling structure and its sense of the uncanny because his Eve is, finally, too good and too protected. Stage Fright fails because its central character is recessive and continually under patriarchal control. Her father and her police detective lover are never far away. She soothes the madman and leads him out of hiding, only to have him escape and be killed by a falling stage curtain. Scorsese puts his Eve—Sam Bowden's daughter Danielle—at greater risk. The unprotected child, marginalized by her bickering parents, is at the mercy of the mad seducer and seemingly all too ready to become his accomplice. Both characters play roles in this scene: Danielle the innocent child; Cady the wise, almost scholarly teacher. But unlike Hitchcock's Eve, Scorsese's has no control and becomes very receptive to Cady's sexual advances. The misogyny here is off-

putting. Scorsese's suggestion that the innocent girl is the willing agent for seduction, and through seduction a weak link between Cady and her father, diverts the intensity of the moral conflict between Cady and Bowden, suggesting finally that Cady—monster though he is—finds ready access for his brutality in the willingness of the women he meets. At least Hitchcock's Eve can control her psychotic friend, though this control is mediated by the male protection that surrounds her.[3]

As I noted, the source sequence in Stage Fright gives the female character an extraordinary amount of control over the madman. In Scorsese's version, the young woman melts in sexual passivity in the face of Cady's seductive menace, for Cady is seduction and brutality; he is the vengeful, destructive father. It is just this destructive impulse that seems to emanate from the ordinary that attracts Scorsese to the two other Hitchcock source films, I Confess and Strangers on a Train . Both films deal with loss of control, with a character who takes over and begins mediating another's life. The primary figures—Father Logan in I Confess and Guy in Strangers on a Train —attempt to live the straightest and most orderly of lives. Their relationship with figures of madness and violence plays out Hitchcock's most obsessive concern: the disruption of the mundane by the unexpected appearance of the uncontrollable destroyer, and the manifestation of that destroyer as a double of the straight and orderly hero.

In I Confess, Hitchcock creates one of his most passive characters (matched only by Manny Balestraro in The Wrong Man, made a few years later in 1957). The narrative is structured upon the unwillingness of Montgomery Clift's Father Logan to identify the handyman Otto Keller, who confesses to him the murder of a man who, coincidentally, has been blackmailing Logan over a love affair he had before becoming a priest. The film fails precisely because of Logan's enforced passivity within a mise-en-scène of unrelenting heaviness. The spaces surrounding Logan are too foreboding, too oppressive for what is essentially a narrative of a man who traps himself within his own theology. Hitchcock permits no breathing space and no alternative for the pitiable oppression of all the characters. Like Bowden in Scorsese's Cape Fear, Father Logan cannot act against his oppressor, who becomes, in effect, his active principle, a figure of otherness, violence, and retribution, who manages not merely to keep the main character under his control but to manifest his impotence at every turn. The difference is that Logan's passivity is based upon religious commitment—a priest cannot expose the man who has confessed to him—whereas Bowden's passivity is based partly upon the seeming indestructibility of Cady but mostly on the fact that it is Cady who carries and exposes the moral imperative. Bowden is paralyzed by the brute and emotional force of his own corruptibility; it is as if there were a pact between him and his double that forces each into the other's embrace. This notion of mutuality is missing from I Confess, which

is why the film only lurks in the background of Cape Fear . But it is central to Strangers on a Train . The notion of an unwitting pact, of characters mirroring one another because of a corrupt and not quite unconscious bond between them, connects the films so strongly that Scorsese reenacts at least three sequences.

Strangers on a Train is the most notable bad film from Hitchcock's early fifties period. Unable to create a usable script with Raymond Chandler, he had it completed by a relatively unknown writer. Unwilling and unable to do anything more than suggest the homosexual implications of the relationship between the two main characters or to follow through on the inherent corruption of the film's putative hero, Guy, Hitchcock palliates his actions by giving Guy a girlfriend—a senator's daughter—whose presence dilutes the narrative and defocuses the mise-en-scène. The best sequences in the film are those between Guy and Bruno, where the former's breathless mock innocence and the latter's chattering and infectious lunacy play off each other in a way that gives neither character the upper hand, but Bruno the lead in a kind of lighthearted maliciousness. The film thrives on their interchanges and on the strange and often amusing appearances of Bruno as Guy's dark watcher, his alter ego calling him into account to execute his part of their contract, that Guy kill Bruno's father in return for his having killed Guy's unpleasant wife. The film breaks apart when it centers upon Guy's relationship with the conventional "good woman" (the "bad" woman, Guy's sexually active wife, is so obnoxious that her death becomes a pleasure, a mere function of Bruno's mischief making, a devaluation of the woman by turning her into a function of her husband's dissatisfaction and his friend's psychosis) and then collapses in the theatrics of the fairground with its out-of-control carousel that kills Bruno. It ends in bathos with the cute interplay between Guy, his intended, and a priest on a train.

The complexity of the film—the little there is of it—lies in its insistence that Guy and Bruno are so intertwined as to be each other's double. Bruno is Guy's secret-sharer who does his murderous deed, emerging from his unconscious to do its bidding. Hitchcock signals this in a series of episodes in which Bruno imposes himself within Guy's and the viewer's visual field, an object of threat that calls one into account, an image of the unconscious made flesh (cf. Barton). Three of Bruno's appearances have this effect. The first occurs after Bruno has killed Guy's wife. Guy returns to his Washington home, and as he goes up the front stairs in the dark (the camera severely canted in a Dutch tilt), Bruno's spectral voice calls to him. A reverse shot reveals nothing but the darkened gate in front of the house. The second reverse shows Bruno emerging from the dark, as if dissolving into presence, beckoning Guy to him with a purposive, exaggerated gesture. The second appearance is in broad daylight. Guy drives by the Jefferson Memorial with a policeman, who is with him to observe his movements (the police

think he has murdered his wife). In a long shot, from Guy's point of view, Bruno is seen, a stark, still, menacing, dark figure against the white columns of the monument, a corruption of the public space, a projection of Guy's bad conscience. The third appearance is at a tennis match, another public space in which Bruno appears, again in a dark suit, completely still amid the spectators, all of whom turn their heads following the play on the field. Bruno stares straight ahead at his alter ego.[4]

For Hitchcock, the dark double dominates the hero's perceptual space and devalues and obliterates the protective aura of the public spaces he inhabits, becoming the sole object of the fearful gaze. For Scorsese, the figure of menace is mostly private, a part of fantasy, a projection of a bad dream. To be sure, Cady appears to Bowden in public. He stares down Bowden during a Fourth of July parade sequence, which has its direct parallel for Scorsese in the tennis match in Strangers on a Train . Like Bruno in the viewing stands, Cady stares out of the crowd straight ahead at Bowden, dominating him and the surroundings. In the Hitchcock film, Guy pursues Bruno after the match, only to find him talking genially with members of Guy's entourage at tea. The parade sequence in Cape Fear occurs early in the film, when Bowden is unclear about Cady's plans and furious at the intrusion into his life. He runs through the parade and attacks his evil twin, only to be pulled back by bystanders who are unaware of Cady's threat. Guy in Strangers is a fairly passive character throughout; he acts as if aware that Bruno is more spectral than real, more him than not. Bowden begins by taking a manly stance before his alter ego, only to find that Cady, like Bruno, is too persistent, clever, and righteous (and, unlike Bruno, too physically powerful) to be easily undone. Bowden too becomes passive, depending, like Bruno, on others in his attempts to outwit Cady. Only at the end of the narrative, when the detectives fall away or are killed, and when the women have failed to subdue the monster during the furious storm, does Bowden do successful physical battle with his alter ego.

The other appearances of Cady that echo Strangers on a Train are of different effect and intent. Here Scorsese specifically presents the villain as fantastic emanation of the main characters, as nightmare. The first occurs after Sam and his wife make love, a sequence rendered unharmonious and troubling as the image turns to negative and Leigh gets out of bed in slow motion, goes to the mirror and applies lipstick, an act interrupted by fades to red. She goes to the window and looks out at the Fourth of July fireworks (suggested, perhaps, by a sequence from Hitchcock's To Catch a Thief, and which is part of the hallucinatory apparatus of the film—Sam and Leigh comment earlier that it is strange to see the fireworks the day before the Fourth). She goes to the window and her gaze is locked by the image of Cady sitting on the garden wall. Three times she sees him, and each time Scorsese returns to her look of amazement and terror, just as

Hitchcock returns to Guy's amazed look when he sees Bruno at the Jefferson Memorial.[5]

Unlike Bruno, Cady is not an emanation solely of the male character. His maliciousness crosses gender and in many ways reflects the film's questions about gender. Scorsese's characters in Cape Fear are filled with sexual anxiety, troubled by domestic discord, and unable to deal with their child, who is just coming into her sexuality. Cady is the very spirit of discord, the insinuation of meanness and sexual panic; he is the trickster, the shape changer who comes in the night to scare people and mess with their lives. He does this when he appears to Leigh on the wall and again in the third appearance that parallels Strangers on a Train . Bowden and a private detective have booby-trapped the house to catch Cady, and Bowden is trying to sleep. He awakes, looks, and Cady appears inside by the window, first in negative, then positive, as Bowden returns the gaze, rubbing his eyes. The sequence parallels Bruno's appearance in the dark in front of Guy's house, beckoning Guy to tell him that he has carried out his part of the "bargain" and killed Guy's wife. Cady's appearance is a reminder too that his violence has been done. He has killed the housekeeper (and, like Norman Bates, put on a wig to look like her) and then killed the private detective. This is the final insinuation. From here the film, sticking close to its source, externalizes the psychological into the physical, climaxing with the bravura pyro-and aquatechnics of the fight on the houseboat in the storm.

Where Bruno acted as a kind of exclamation point for Guy, a sharp reminder that his hoped-for life of calm and fame as the tennis-playing husband of a senator's daughter might not work, Cady is a dash—on the other side of which are obscene phrases and threatening remarks, the violence of a corrupted heterosexuality and the meanness of religious hysteria. Bruno was a clear marker of Guy's potential murderousness and his attraction to the sexual other. In the early fifties, Hitchcock was still able and willing to circumscribe his doubles, to localize and finally recuperate the good twin back into a life that might not be normal (after all, he or she was contaminated by the experience with the other, and from the early forties on, the "happy endings" that Hitchcock was compelled to attach to his narratives were deeply compromised by the narrative events that came before). By the time he made Vertigo and Psycho, there was no need for a polite recuperation. In the latter film particularly, the claustrophobic world that surrounded the characters who were each others' shadow encapsulated the culture at large and signaled the end of the possibility of redemption. Scorsese adopts this grim view. The characters of Cape Fear do not triumph with the hard death of Cady, just as Guy is never completely freed of Bruno or the audience itself completely freed of Norman Bates.

Throughout the fifties, Hitchcock was thinking about domesticity. Along with Sirk and Nicholas Ray, though more darkly and with a greater sense

of terror, he represented in film the culture's own fears of eruptions from the inside and threats from the outside. He spoke of the domestic as the place of vulnerability and danger. Hitchcock went further than most in his perception of domestic arrangements as dead places where madness dwells. No longer a barrier against the unknown and unwanted, the domestic was the shell that only barely kept evil and corruption from spilling out. Psycho proposes the necessary eruption of evil out of the protective barrier of the domestic fantasy of corruption or, more accurately, and according to its own imagery, a swirling down into the swamp of despair of all illusions of safety and control, all rational fantasies of the domestic. Thompson's Cape Fear domesticates this vision. While it reproduces the figure of madness imposing itself upon the middle-class family and threatens it with sexual release, it manages to return some measure of control to the good man and to allow the family a measure of recuperation.

Scorsese's Cape Fear directly extends the Hitchcockian proposal of Psycho while speaking to the nineties' belief that corruption is the norm and will appear to spoil any pleasure that might be fantasized. Eliding the fifties domestic melodrama into Psycho 's response to these films, referring to Hitchcock's doubles films of the early part of the fifties, and then adding to the mix Nightmare on Elm Street and its sequels and such items as Fatal Attraction, Pacific Heights, Sleeping with the Enemy, and their ilk, Scorsese makes a film that speaks of an ongoing danger to a never stable and always illusory harmoniousness. (He speaks as well, with an almost ideal cynicism, to his audience's desire to be frightened by the ineluctable presence of destructive corruption.) In his Cape Fear and its predecessors, the domestic scene is always already troubled and discordant. Max Cady appears only as the final agent of this discordance, as bad conscience, evil twin, and lord of misrule—the innate violence of the family given flesh, its sexual repressions unleashed (see figure 4).

Cape Fear is a film of accretions; it builds upon its predecessors and then exaggerates their various parts. The specific Hitchcock allusions help keep it grounded, somewhat. They help introduce a measure of moral ambiguity within a film that otherwise throws all moral concerns to the winds in its quest for the bloodiest and most sexually violent effects. As if Scorsese were aware that, in this film made for the purest commercial reasons, there would have to be an anchor for a filmmaker who was able to seed commercial conventions with unconventional perception, he calls upon Hitchcock as an aesthetic and narrative source. Hitchcock becomes Cape Fear 's point of good faith, part of the calculation of an equation that maintains connections, factors in film history, and yields a few interesting returns. Were Cape Fear a better film, it would have further interrogated the possibilities of restating certain Hitchcockian perceptions and premises. As it is, it confirms Scorsese's own best modernist impulses and the ongoing usefulness

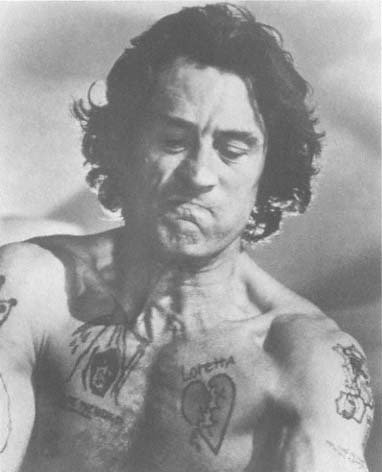

Figure 4.

Robert DeNiro as evil twin and lord of misrule in Martin Scorsese's

Cape Fear (1991), the remake. Photograph by Phil Caruso.

of Hitchcock to filmmakers who know the importance of maintaining links, of borrowing and alluding as a means of maintaining ground and balance. A calculated risk.

Works Cited

Anobile, Richard J. Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho. New York: Avon Books, 1974.

Barton, Sabrina. "'Criss-Cross': Paranoia and Projection in Strangers on a Train ." Camera Obscura , no. 25–26 (1991).

Carroll, Noël. "The Future of Allusion: Hollywood in the Seventies (and Beyond)." October , no. 20 (spring 1982).

Kapsis, Robert E. Hitchcock: The Making of a Reputation . Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1992.

Modleski, Tania. The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory. New York and London: Methuen, 1991.

Truffaut, François. Hitchcock. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984.

Wood, Robin. "The American Nightmare: Horror in the Seventies." Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan. New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1986.