Much Ado about Nun-Things:

Black Narcissus and Damned If You Don't

By shifting the central organizing perspective of her science fiction film from male to female, Valie Export begins to "rewrite gender within genre" (White, 1987, 84). But, as Judith Butler argues, sex, gender and desire are not necessarily synonymous: "Gender can denote a unity of experience, of sex, gender and desire, only when sex can be understood in some sense to necessitate gender—where gender is a psychic and/or cultural designation of the self—and desre—where desire is heterosexual and therefore differentiates itself through an oppositional relation to that other gender it desires. . . . This conception of gender presupposes not only a causal relation among sex, gender, and desire, but suggests as well that gender reflects or expresses desire" (1990, 22).

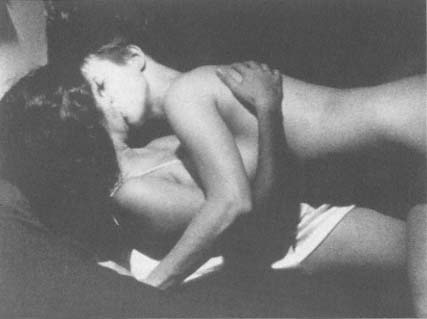

As "the narrative form that takes desire as its subject" (Lang, 1989, 12), melodrama offers a more logical site than science fiction for cinematic investigations of the connections and disjunctures among sex, gender, and desire. Damned If You Don't, Su Friedrich's makeover (and more) of Black Narcissus, successfully adopts this strategy, highlighting how much Black Narcissus and melodrama in general are predicated on the assumption that all desire is heterosexual. Snipping up, then reconstructing Powell and Pressburger's original tragedy of unrequited (white) heterosexual love, madness, and death, Friedrich instead proposes a narrative with a happy ending for lesbians: for once the (Latina) girl, not the boy, gets the (white) girl, and no one dies or goes insane.[25] By the end of Damned If You Don't, lesbianism is no longer a sickly copy of a healthy heterosexual original. (See figure 26.)

The same spirit pervades both Black Narcissus and Damned If You Don't . Both make nuns the central characters of stories where, as Friedrich pointedly puts it, "the chaste are chased" (Hanlon, 1982–83, 81). Both are highly sensual, though, as Michael Powell says of Black Narcissus, "it is all done by suggestion" (1987, 584). Unlike Export, moreover, Friedrich is quite willing to acknowledge her debts to and appreciation of Black Narcissus, even as she manipulates and criticizes several of its basic premises. Like Export, she includes a variety of other material in her film, thereby altering the shape of the original.

But where Export's celluloid surgery of Invasion of the Body Snatchers is ongoing and multiple, Damned If You Don't' s relationship to Black Narcissus is like a single large implant: for the most part the Black Narcissus makeover is confined to the first eight minutes of Damned If You Don't, although a few

Figure 26.

Lovers embrace in Su Friedrich's Damned If You Don't (1987), a transgressive

retake on Powell and Pressburger's 1946 melodrama, Black Narcissus .

Black Narcissus images reappear briefly at the end as well. Even within this implant, however, Friedrich sets other more minor alterations in motion, then further amplifies and modifies these alterations in the rest of the film. Cinematically, within the Black Narcissus sequence and indeed elsewhere as well, Damned If You Don't is more restrained than Black Narcissus, though no less compelling. Narratively, the two films differ in three key and overlapping areas: 1) how they portray the two lead female characters; 2) whether and how they represent male characters; and 3) how they inscribe racial and ethnic difference.

Rather than contrast virility and femininity, repression and expression, West and East as Powell and Pressburger do, Friedrich takes a different tack. For the most part Damned If You Don't excises Black Narcissus' imperialist fantasies. Gone are the lush but artificial settings created in British studios through matte shots, glass shots, and painted backdrops or, as in the case of the subtropical gardens filled with "cedars, deodars, rhododendrons and azaleas," literally transported from India to England by retired "merchant princes and pro-consuls" (Powell, 1987, 562).[26] Gone too is the incessant drumming of the natives, and gone is almost all reference to any "Indian"

characters. Except for one brief shot of Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) and Kanchi (Jean Simmons), the "sexy little piece who attracts the eye of the young Prince" (Sabu) (Powell, 1987, 576),[27] the Malays, Indians, Gurkhas, Nepalese, Hindus, and Pakistanis Powell and Pressburger indiscriminately cast as Indians have been cut from Friedrich's film.[28] In the stripped-down, stitched-up version of Black Narcissus she offers, the principal characters are known only as the Good Nun (Deborah Kerr), the Bad Nun (Kathleen Byron), and Mr. Dean (David Farrar).

The offscreen female narrator of the Black Narcissus sequence (Martina Siebert) only mentions the Orient twice, in passing. Each time she mocks the racism signaled so blithely in the very title of Powell and Pressburger's film: "Black Narcissus" is the name of the cheap perfume the young prince wears.[29] In Black Narcissus the young prince proudly tells the nuns his perfume comes from the Army Navy Stores of London. "I'll call him Black Narcissus," Sister Ruth, the Bad Nun, says when he leaves. "He's so vain, like a peacock. A fine black peacock." "He's not black," another nun replies. "They all look alike to me," Sister Ruth retorts.

In Damned If You Don't, in contrast, Siebert's offbeat voice-over—which includes, for example, such lines as "[the nuns] forgive [Mr. Dean] for arriving naked, given the state of emergency"—makes the melodrama she recounts seem more like a comedy. Rather than talk of the need to "humanize" the natives, as Mr. Dean and the nuns do, Siebert says flippantly that the nuns "work hard, day and night, bringing aspirin and the English language to Indian peasants." The flatness of her delivery detracts from any exoticism that might attach to her German accent. She also directly links racism to sexism: "[The Good Nun] asks [Mr. Dean] why the local people can't be more disciplined, which somehow raises the question of whether or not she likes children." The Black Narcissus sequence she refers to is more overtly racist, but it disguises sexism as flirtation: wearing shorts, a shirt, and a hat, Mr. Dean crosses and uncrosses his hairy legs and glances "meaningfully" at Sister Clodagh, all the while insisting that the "natives" are "primitive people . . . like children, primitive children."

At only one moment does Friedrich incorporate text from Black Narcissus . The Good Nun says, "If you have a spark of decency left in you, you won't come near us again." Then Friedrich interrupts Siebert's narration to sing Mr. Dean's song herself: "No I won't be a nun, no I shall not be a nun, for I am so fond of pleasure, I cannot be a nun." The pastiche is doubly gender bending: first, because a man sings a song "only" a woman should sing since "only" women can be nuns;[30] second, because a woman, Friedrich, sings a song "originally" sung by a man. Only at the end of the segment do we hear Mr. Dean himself sing the song. Now, however, he does so over medium two-shots of the Good and the Bad Nuns. (See figure 27.)

Figure 27.

The nun in Su Friedrich's experimental makeover, Damned If

You Don't (1987), raises questions of identity and gender.

Friedrich performs other more minor surgical operations on her eight-minute Black Narcissus segment as well. Roll bars flicker across the screen since she has taken the images from a television broadcast without standardizing them to film. Periodic cutaways show a woman who will become one of the main characters of Friedrich's primary narrative (Ela Troyano) pouring herself a glass of wine, then settling in to watch Powell and Pressburger's film on TV, and finally falling asleep.

Friedrich's reshaping of the Black Narcissus implant leaves no doubt about what the lesbian character of her main narrative finds to like in Powell and Pressburger's melodrama. She abbreviates and reframes several shots in order to insist on the exchanges of looks between the Good Nun and the Bad Nun. As a result, the force of their desire and rivalry for Mr. Dean imperceptibly acquires another, lesbian, layer.[31] As Martha Gever says, Friedrich "tells . . . the story of passionate relationships between women within the film's male-centered narrative—by concentrating on the key moments in the rivalry between two female characters" (1988, 16). With the amputation of Kanchi and the young general from the Black Narcissus segment, happy heterosexual love disappears entirely from Damned If You Don't,

leaving only what Friedrich calls "the sexual hysteria at the core of the film" (MacDonald, 1992, 304).

In the final analysis, however, Friedrich's makeover is more a reverent restatement than an outright rejection, as much the enhancement of secondary celluloid characteristics as the castration of primary ones. Friedrich says she appreciates, for example, "the really high drama of Black Narcissus . . . . Powell and Pressburger used lighting to such great effect and created a lot of expression in the faces, which is all you have to work with when you're dealing with characters who are completely covered" (MacDonald, 1992, 304). Damned If You Don't translates this drama into its own terms, using black and white instead of color. For the most part, Friedrich's reconstruction of Black Narcissus refuses the canted angles, extreme long shots, dramatic framing, superimpositions, dissolves, and flashbacks of the original. Instead Friedrich insists on meter and tempo, editing "the rhythm of gestures within the shot . . . with the rhythm of the roll bars, [and] . . . the cadence of the speech at the moment" (MacDonald, 1992, 304–5).

Friedrich admits that "what I felt I was doing by beginning with the Black Narcissus material was saying, "Okay, you want a narrative, here, take it: you can have it. And you can have it just for its high points, you don't have to slog through all the bullshit, all the transitions" (MacDonald, 1992, 306). Yet Black Narcissus functions not only as hook but also as model for the rest of Damned If You Don't, in that Friedrich's film remains a dramatic narrative, though Friedrich adds "god forbid, a happy ending" (Friedrich, 1989–90, 123).

In many ways, therefore, Friedrich's implant of Black Narcissus becomes the basis for the new celluloid body that is Damned If You Don't . The woman (known only as the Other Woman) who watched Powell and Pressburger's film at the beginning of Damned If You Don't adapts elements from the former to fit her own devious designs. At one point she even buys a needle-point head of Christ as a gift for the next door neighbor, the Nun (Peggy Healey), whom she desires. Friedrich carries on Powell and Pressburger's emphases on framing and costuming as well, insisting as they do on the sensuality of spirituality. On an outing to the New York City Aquarium, for example, the Nun watches white whales swim within their tank. Her black robe and white face visually echo their white bodies on the black water. Later images of her in her tiny room or behind grillwork make it clear that she too is a prisoner. The Other Woman's restless movements, dark good looks and flamboyant clothes (black bolero pants, tight tops, a low-cut and diaphanous black party dress), offer a conspicuous contrast to the Nun and combine eroticism and exoticism just as Sister Ruth and especially Kanchi did in Black Narcissus .

Except for the offscreen voice of a priest, there are no male characters at all in the main story of Damned If You Don't . All the watching, all the

desiring that occurs in the constant shot/reverse shots, point-of-view shots and eyeline matches takes place between women. Finally the Nun gives in to desire and decides to love her neighbor as herself. The Other Woman slowly unveils her, and the two make love in silence—a major shift from Black Narcissus' operatic climax, where "music, emotions, images and voices are blended together into a new and splendid whole" (Powell, 1987, 583) as, mad with jealousy and grief because Mr. Dean has rejected her, Sister Ruth tries to kill Sister Clodagh by pushing her off a cliff. Instead she slips and falls to her death. The final credits of Friedrich's film unfold, appropriately enough, to the lascivious lyrics and raucous tune of Patti Smith's "Break It Up."

Two other subnarratives, both of which reinforce the main story's emphasis on the virtues of lesbian love, are grafted onto the sound track of Damned If You Don't . The first set of grafts is excerpted from Judith Brown's Immodest Acts , a study of a nun found guilty of "misconduct" in Renaissance Italy and imprisoned for thirty-five years in prison within her convent.[32] Friedrich also interrupts the first of the two selections she includes. An offscreen narrator (Cathy Quinlan) reads Sister Crivelli's testimony that, as she watched, Jesus removed Sister Benedetta's heart and replaced it with his own. Quinlan chuckles as she says, "How can I live without a heart now?" "Well, why not?" Friedrich's voice responds. Stepping completely out of character, Quinlan says, "You know what? I just had the funny idea that Sister Crivelli said this millions of times too. At a certain point she was just reading the fucking testimony." The second selection, which describes a series of lesbian sex acts in graphic detail, is uninterrupted.

By grafting sections from Immodest Acts onto and into her main story, Friedrich implicitly reclaims past lesbians for the present. Periodically, if more parenthetically, a second set of grafts tells of other lesbian love stories. At one point an anonymous voice on the sound track asserts that the nuns she had crushes on as a child were lesbians. Onscreen we see still other nuns framed in two-shots or three-shots. By association they too become lesbians, or at least potential lesbians.

Each and every element of Friedrich's film, including her implant of Black Narcissus , thus hints at the persistence of lesbian desire through time and across cultures, despite silencing and persecution. By the end of Damned If You Don't , heterosexual melodrama has, in effect, been "lesbianized." The moral of Friedrich's film is quite unequivocal: here you're only "damned if you don't."

But while the moral of Damned If You Don't is unequivocal, its address and its referents are not. Who is the "you" in the title? Who will be "damned if they don't?"[33] Only women? Only lesbians? Only white and Latina lesbians? Friedrich's decision to focus on the role played by sexuality in melodrama, like Export's decision to focus on the impact of gender on science

fiction, pushes questions of racial and ethnic difference to the background. Even though each acknowledges in passing that such differences exist—Friedrich through her ironic commentary about Black Narcissus and casting of Troyano and Healey; Export through the offscreen news stories and the documentary images of destruction and disaster in third world countries—"white" remains the dominant, and hence the invisible, color in both films.